Abstract

The purpose of this study was to extend our knowledge of the genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships among the North American Tacaribe serocomplex viruses. Analyses of glycoprotein precursor gene sequence data separated the North American arenaviruses into 7 major phylogenetic groups. The results of analyses of Z gene and nucleocapsid protein gene sequence data were not remarkably different from the glycoprotein precursor gene tree. In contrast, the tree generated from RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene sequences differed from the glycoprotein precursor gene tree with regard to phylogenetic relationships among the viruses associated with woodrats captured in the western United States, Texas, or northern Mexico. Further analyses of the polymerase gene sequence data set suggested that the difference in topology was a consequence of incongruence among the gene tree data sets or chance rather than genetic reassortment or recombination between arenaviruses.

Keywords: Arenaviridae, Arenavirus, California mouse, Cotton rat, Neotoma, Peromyscus californicus, Sigmodon hispidus, Tacaribe serocomplex, Woodrat

Introduction

The Tacaribe serocomplex (virus family Arenaviridae, genus Arenavirus) comprises Bear Canyon virus (BCNV), Tamiami virus (TAMV), and Whitewater Arroyo virus (WWAV) in the United States, Tacaribe virus (TCRV) on Trinidad Island, and 14 species in South America. Provisional species in the Tacaribe serocomplex include Big Brushy Tank virus (BBTV), Catarina virus (CTNV), Skinner Tank virus (SKTV), and Tonto Creek virus (TTCV) in the United States (Cajimat et al. 2007a, 2008; Milazzo et al. 2008), and Real de Catorce virus (RCTV) in Mexico (Inizan et al. 2010).

Five South American arenaviruses naturally cause severe febrile illnesses in humans: Guanarito virus (GTOV) in Venezuela, Junín virus (JUNV) in Argentina, Chaparé virus (CHPV) and Machupo virus (MACV) in Bolivia, Sabiá virus (SABV) in Brazil (Delgado et al. 2008, Peters 2002). The results of a recently published study (Milazzo et al. 2011) indicated that WWAV or arenaviruses antigenically closely related to the WWAV prototype strain AV 9310135 are etiological agents of acute central nervous system disease or undifferentiated febrile illnesses in humans in the United States.

Specific members of the rodent family Cricetidae (Musser and Carleton 2005) are the principal hosts of the Tacaribe serocomplex viruses for which natural host relationships have been well characterized. For example, the short-tailed cane mouse (Zygodontomys brevicauda) in western Venezuela is the principal host of GTOV (Fulhorst et al. 1997, 1999) and the drylands vesper mouse (Calomys musculinus) in central Argentina is the principal host of JUNV (Mills et al. 1992).

The recorded history of the Tacaribe serocomplex viruses in North America began in 1970 with the discovery of TAMV in hispid cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus) captured in southern Florida (Calisher et al. 1970). Subsequently, WWAV was isolated from woodrats (presumed to be Neotoma albigula) captured in northwestern New Mexico (Fulhorst et al. 1996); Tacaribe serocomplex viruses were isolated from white-throated woodrats (N. albigula), a bushy-tailed woodrat (N. cinerea), Mexican woodrats (N. mexicana), large-eared woodrats (N. macrotis), southern plains woodrats (N. micropus), and California mice (Peromyscus californicus) captured at other localities in the United States (Cajimat et al. 2007b, 2008; Fulhorst et al. 2001, 2002a, 2002b; Milazzo et al. 2008); antibodies (IgG) to Tacaribe serocomplex viruses were found in cricetid rodents captured in San Luis Potosí and 9 other states in Mexico (Milazzo et al. 2010); and RNA of RCTV was found in white-toothed woodrats (N. leucodon) captured in San Luis Potosí (Inizan et al. 2010).

The genomes of arenaviruses consist of 2 single-stranded, negative-sense RNA segments, designated small (S) and large (L) (Salvato et al. 2005). The S segment (~3.5 kb) consists of a 5’ non-coding region (NCR), the glycoprotein precursor (GPC) gene, an intergenic region, the nucleocapsid (N) protein gene, and a 3’ NCR. Similarly, the L segment (~7.3 kb) consists of a 5’ NCR, the Z gene, an intergenic region, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene, and a 3’ NCR. Our most comprehensive knowledge of the phylogenetic relationships among the North American arenaviruses prior to this study was based on the results of analyses of GPC gene and N protein gene sequences (Inizan et al. 2010). The objective of this study was to increase our knowledge of the genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships among the North American Tacaribe serocomplex viruses. This objective was accomplished through analyses of all 4 viral genes.

Results

The North American viruses in this study (Table 1) were selected to represent the known geographical distribution and natural host associations of the Tacaribe serocomplex viruses native to North America (Figure 1). The nucleotide sequences of the GPC genes and N protein genes of 6 viruses, nucleotide sequences of the Z genes of 15 viruses, and nucleotide sequences of a 2142- to 2151-nt fragment of the RdRp genes of 16 viruses were determined in this study (Table 2). Multiple attempts to amplify a fragment of the 5’ end of the L segment of RCTV strain AV H0030026 were unsuccessful; consequently, the analyses of Z gene sequence data did not include RCTV strain AV H0030026. The 2142- to 2151-nt fragment of the L genomic segment included the 3’ end of the RdRp gene. The lengths of the GPC, N protein, Z, and RdRp gene sequence alignments were 1641, 1728, 306, and 2253 characters, respectively.

Table 1.

North American Tacaribe serocomplex viruses included in the analyses of nucleotide and amino acid sequence data

| Virus Speciesa |

Virus strainb | Hostc | Date captured |

Stated | County or Municipality |

Locality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCNV | AV A0060209 | Pcal (TK90599) | Jun 11, 1998 | CA | Orange | El Cariso #2 |

| BCNV | AV 98470029 | Nmac (TK83707) | Sep 22, 1998 | CA | Riverside | Lake Elsinore |

| BCNV | AV A0070039 | Pcal (TK90438) | Nov 13, 1998 | CA | Riverside | Bear Canyon Trailhead |

| BCNV | AV B0300052 | Nmac (TK91001) | Jan 19, 2000 | CA | Los Angeles | Zuma Canyon |

| BBTV | AV D0390174 | Nalb (TK114533) | Feb 13, 2002 | AZ | Graham | Brushy Tank |

| BBTV | AV D0390324 | Nalb (TK114581) | Feb 15, 2002 | AZ | Graham | Hackberry Creek |

| CTNV | AV A0400135 | Nmic (TK84703) | Jul 19, 1999 | TX | Dimmit | CWMAe |

| CTNV | AV A0400212 | Nmic (TK84816) | Jul 20, 1999 | TX | La Salle | CWMAe |

| RCTV | AV H0030026 | Nleu (TK133448) | Aug 5, 2005 | SLP | Catorce | Real de Catorce |

| SKTV | AV D1000090 | Nmex (TK119202) | Aug 9, 2002 | AZ | Coconino | Skinner Tank |

| TAMV | W·10777 | Shis | Jan 5, 1965 | FL | Hendry | Everglades National Park |

| TAMV | AV 97140103 | Shis (FSH33) | Jul 10,1997 | FL | Miami-Dade | Homestead Air Force Base |

| TTCV | AV D0150144 | Nalb (TK93637) | Nov 7, 2001 | AZ | Gila | White Cow Mine |

| TTCV | AV D0390060 | Nalb (TK113981) | Jan 6, 2002 | AZ | Gila | Cherry Creek |

| WWAV | AV 9310135 | Nalb (1627) | Jul 15, 1993 | NM | McKinley | Whitewater Arroyo |

| WWAV | AV 96010024 | Nmex (36282) | Jul 5, 1994 | UT | San Juan | NBNMe |

| WWAV | AV 96010025 | Ncin (36287) | Jul 6, 1994 | UT | San Juan | NBNMe |

| WWAV | AV 96010151 | Nmex (62425) | Sep 24, 1994 | NM | Socorro | Magdalena Mountains |

| WWAV | AV 98490013 | Nmic (TK28731) | Oct 12, 1985 | OK | Cimarron | Black Mesa |

| WWAV | TVP·6038 | Nleu (TK28742) | Oct 12, 1985 | OK | Cimarron | Black Mesa |

| WWAV | AV D1240007 | Nmex (TK123380) | Oct 3, 2002 | CO | Larimer | Big Thompson Canyon |

| WWAV | AV H0380005 | Nmic (TK77260) | May 21, 1998 | NM | Otero | Fort Bliss |

BCNV, Bear Canyon virus; BBTV, Big Brushy Tank virus; CTNV, Catarina virus; RCTV, Real de Catorce virus; SKTV, Skinner Tank virus; TAMV, Tamiami virus; TTCV, Tonto Creek virus; WWAV, Whitewater Arroyo species complex.

BCNV strains A0060029 and AV A0070039, TAMV strain AV 97140103, and TTCV strain AV D0150144 were isolated from brain. BCNV strain AV 98470029, TAMV strain W·10777, and TVP·6038 were isolated from samples of spleen, heart, and liver, respectively. The 15 other strains were isolated from samples of kidney.

Rodent species (museum accession number). Nalb, Neotoma albigula; Ncin, N. cinerea; Nleu, N. leucodon; Nmac, N. macrotis; Nmex, N. mexicana; Nmic, N. micropus; Pcal, Peromyscus californicus; Shis, Sigmodon hispidus.

Rodents TK28731 and TK28742 were identified as white-throated woodrats (N. albigula) in a previously published study (Fulhorst et al. 2001); however, an analysis of cytochrome-b gene sequence data indicated that these rodents were a southern plains woodrat (N. micropus) and white-toothed woodrat (N. leucodon), respectively (Appendix 1).

AZ, Arizona; CA, California; CO, Colorado; FL, Florida; NM, New Mexico; OK, Oklahoma; SLP, San Luis Potosí; TX, Texas; UT, Utah.

CWMA, Chaparral Wildlife Management Area; NBNM, Natural Bridges National Monument.

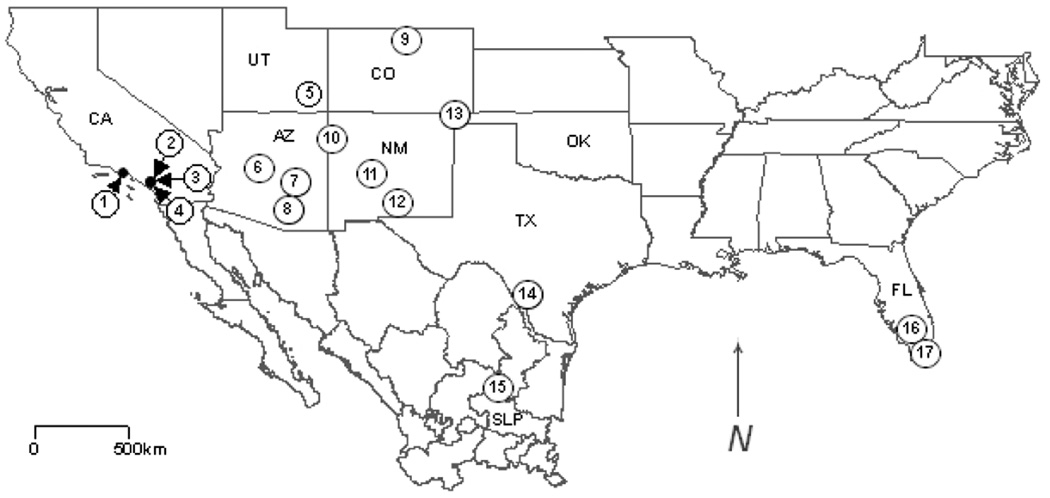

Figure 1.

Map of the southern United States and northern Mexico marked to show the localities at which the virus-positive rodents were captured: (1) TK91001 (Neotoma macrotis) – Bear Canyon virus (BCNV) strain AV B0300052; (2) TK90599 (Peromyscus californicus) – BCNV strain AV A0060209; (3) TK83707 (N. macrotis) – BCNV strain AV 98470029; (4) TK90438 (P. californicus) – BCNV strain AV A0070039; (5) 36282 (N. mexicana) – AV 96010024, 36287 (N. cinerea) – AV 96010025; (6) TK119202 (N. mexicana) – Skinner Tank virus strain AV D1000090; (7) TK93637 (N. albigula) – Tonto Creek virus (TTCV) strain AV D0150144, TK113981 (N. albigula) – TTCV strain AV D0390060; (8) TK114533 (N. albigula) – Big Brushy Tank virus (BBTV) strain AV D0390174, TK114581 (N. albigula) – BBTV strain AV D0390324; (9) TK123380 (N. mexicana) – AV D1240007; (10) 1627 (N. albigula) – Whitewater Arroyo virus strain AV 9310135; (11) 62425 (N. mexicana) – AV 96010151; (12) TK77260 (N. micropus) – AV H0380005; (13) TK28731 (N. micropus) – AV 98490013, TK28742 (N. leucodon) – TVP·6038; (14) TK84703 (N. micropus) – Catarina virus (CTNV) strain AV A0400135, TK84816 (N. micropus) – CTNV strain AV A0400212; (15) TK133448 (N. leucodon) – Real de Catorce virus strain AV H0030026; (16) Sigmodon hispidus – Tamiami virus strain W·10777; (17) FSH33 (S. hispidus) – AV 97140103. AZ, Arizona; CA, California; CO, Colorado; FL, Florida; NM, New Mexico; OK, Oklahoma; SLP, San Luis Potosí; TX, Texas; UT, Utah. The geographical coordinates of the localities are listed in Appendix 1.

Table 2.

North American Tacaribe serocomplex viruses included in the analyses of the glycoprotein precursor (GPC), nucleocapsid (N) protein, Z, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene sequences

| Genbank Accession Number |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speciesa | Strain | GPC gene | N protein gene | Z gene | RdRp gene |

| Bear Canyon virus | AV A0060209 | AF512833 | AY216503 | ||

| Bear Canyon virus | AV 98470029 | AY924392 | JF430462b | EU938656b | |

| Bear Canyon virus | AV A0070039 | AY924391 | AY924390 | ||

| Bear Canyon virus | AV B0300052 | FJ907243b | FJ907244b | -- | -- |

| Big Brushy Tank virus | AV D0390174 | EF619035 | JF430471b | EU938665b | |

| Big Brushy Tank virus | AV D0390324 | EF619036 | JF430472b | EU938666b | |

| Catarina virus | AV A0400135 | DQ865244 | JF430463b | EU938657b | |

| Catarina virus | AV A0400212 | DQ865245 | JF430464b | EU938658b | |

| Real de Catorce virus | AV H0030026 | GQ903697 | -- | JF430461b | |

| Skinner Tank virus | AV D1000090 | EU123328 | JF430465b | EU938659b | |

| Tamiami virus | W·10777 | AF512828 | AY924393 | ||

| Tamiami virus | AV 97140103 | EU486821b | JF430474b | EU938668b | |

| Tonto Creek virus | AV D0150144 | EF619033 | JF430469b | EU938663b | |

| Tonto Creek virus | AV D0390060 | EF619034 | JF430470b | EU938664b | |

| Whitewater Arroyo virus | AV 9310135 | AF228063 | AY924395 | ||

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV 96010024 | EU123331 | JF430468b | EU938662b | |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV 96010025 | EU486820b | JF430473b | EU938667b | |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV 96010151 | EU123330 | JF430467b | EU938661b | |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV 98490013 | FJ032026b | FJ032027b | JF430476b | EU938670b |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | TVP·6038 | FJ719106b | FJ719107b | -- | -- |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV D1240007 | EU123329 | JF430466b | EU938660b | |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV H0380005 | EU910959b | JF430475b | EU938669b | |

Big Brushy Tank virus, Catarina virus, Real de Catorce virus, Skinner Tank virus, and Tonto Creek virus are provisional species in the family Arenaviridae. Strains AV 96010024, AV 96010025, AV 96010151, AV 98490013,TVP·6038, AV D1240007, and AV H0380005 are members of the Whitewater Arroyo species complex (see Discussion).

Nucleotide sequence determined in this study.

Genetic diversity among the North American arenaviruses

Nonidentities between the nucleotide sequences of the GPC genes, N protein genes, Z genes, and RdRp genes of strains of the same species ranged from 1.9% (BCNV strains AV A0070039 and AV 98470029) to 16.2% (TTCV strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060), 2.0% (BCNV strains AV A0070039 and AV 98470029) to 12.7% (BCNV strains AV A0060209 and AV B0300052, and TTCV strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060), 1.7% (BCNV strains AV A0060209 and AV A0070039, BCNV strains AV A0070039 and AV 98470029) to 12.2% (TTCV strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060), and 1.9% (BCNV strains AV A0070039 and AV 98470029) to 14.5% (TTCV strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060), respectively. Nonidentities between the nucleotide sequences of the GPC genes, N protein genes, Z genes, and RdRp genes of AV 97140103 and TAMV strain W·10777 were 16.7%, 15.0%, 13.9%, and 18.4%, respectively. Lastly, nonidentities among the nucleotide sequences of the GPC genes, N protein genes, Z genes, and RdRp genes of strains of different North American species were as high as 38.9% (BCNV strain AV B0300052 and WWAV strain AV 9310135), 28.4% (BCNV strain AV A0070039 and CTNV strain AV A0400135, and BCNV strain AV 98470029 and CTNV strain AV A0400135), 31.9% (TAMV strain W·10777 and WWAV strain AV 9310135), and 37.2% (BCNV strain AV A0070039 and TAMV strain W·10777), respectively.

Phylogenetic relationships among the North American arenaviruses

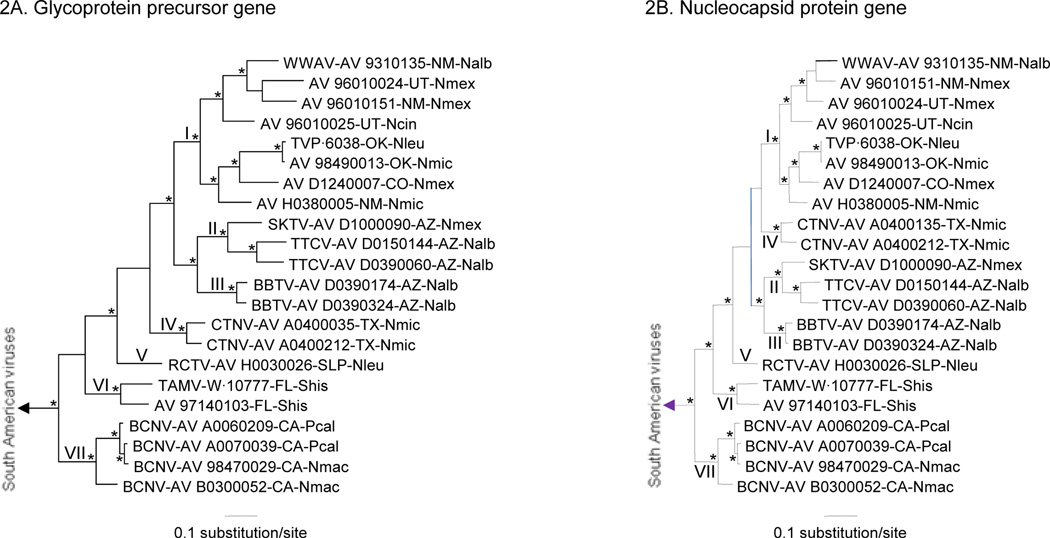

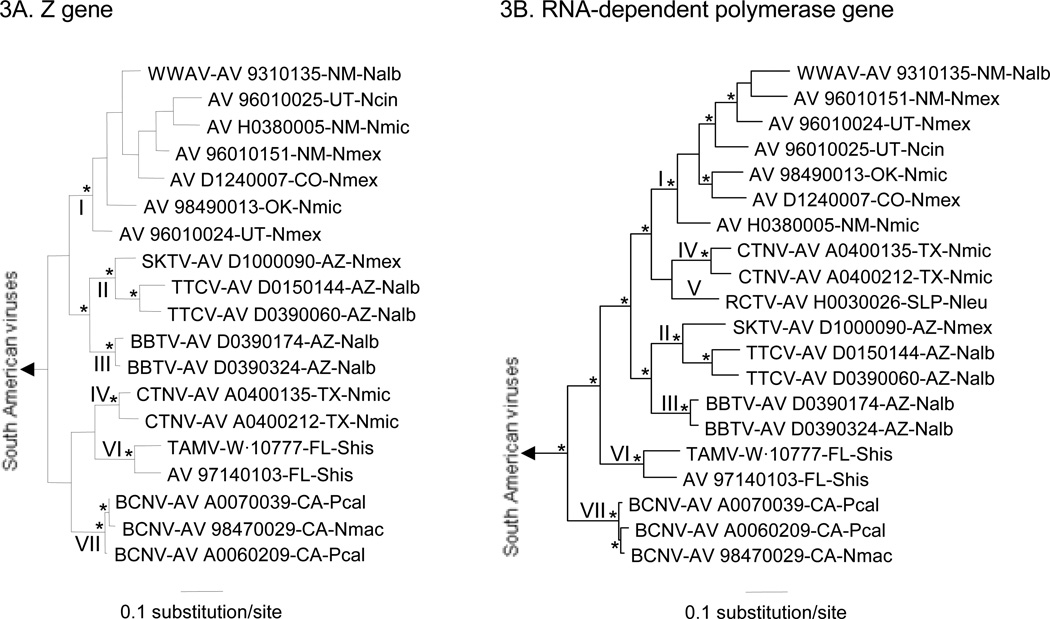

Bayesian analyses of the GPC gene sequences, N protein gene sequences, Z gene sequences, and RdRp gene sequences separated the North American Tacaribe serocomplex viruses from the South American Tacaribe serocomplex viruses. The Bayesian analyses of the GPC gene sequences, N protein gene sequences, and RdRp gene sequences also separated the North American viruses into 7 major phylogenetic groups: I – AV 96010024, AV 96010025, AV 96010151, TVP·6038, AV 98490013, AV D1240007, AV H0380005, WWAV strain AV 9310135; II –SKTV strain AV D1000090, TTCV strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060; III – BBTV strains AV D0390174 and AV D0390324; IV – CTNV strains AV A0400135 and AV A0400212; V – RCTV strain AV H0030026; VI – AV 97140103, TAMV strain W·10777; VII – BCNV strains AV A0060209, AV A0070039, AV B0300052, and AV 98470029 (Figures 2A, 2B, and 3B). The Bayesian analyses of the Z gene sequences, which did not include RCTV strain AV H0030026, separated the North American viruses into 6 major groups (Figure 3A), with each group represented in the GPC, N protein, and RdRp gene trees.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationships among the North American Tacaribe serocomplex viruses based on Bayesian analyses of (2A) complete glycoprotein precursor gene sequences and (2B) complete nucleocapsid protein gene sequences. The length of each scale bar is equivalent to 0.1 substitution per site. Probability values in support of the clades were calculated a posteriori, clades with probability values ≥ 0.95 were considered supported by the data, and an asterisk at a node indicates that the clade was supported by the data. The Roman numerals indicate the major phylogenetic groups represented by the North American viruses included in the analyses. The branch labels include (in the following order) virus species, strain, state, and host species. BBTV, Big Brushy Tank virus; BCNV, Bear Canyon virus; CTNV, Catarina virus; SKTV, Skinner Tank virus; TAMV, Tamiami virus; TTCV, Tonto Creek virus; WWAV, Whitewater Arroyo virus. AZ, Arizona; CA, California; CO, Colorado; FL, Florida; NM, New Mexico; OK, Oklahoma; SLP, San Luis Potosí; TX, Texas; UT, Utah. Nalb, Neotoma albigula; Ncin, N. cinerea; Nleu, N. leucodon; Nmac, N. macrotis; Nmex, N. mexicana; Nmic, N. micropus; Pcal, Peromyscus californicus; Shis, Sigmodon hispidus. The Guanarito virus prototype strain INH-95551 (a South American Tacaribe serocomplex virus) was the designated outgroup in each analysis.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationships among the North American Tacaribe serocomplex viruses based on Bayesian analyses of (3A) complete Z gene sequences and (3B) the nucleotide sequences of a 2142- to 2151-nt fragment of the RdRp gene. The length of each scale bar is equivalent to 0.1 substitution per site. Nodal support, Roman numerals, branch labels, and the outgroup in each analysis are as in Figure 2.

The topologies of the N protein gene tree (Figure 2B) and Z gene tree (Figure 3A) were not remarkably different from the topology of the GPC tree (Figure 2A). In contrast, the RdRp gene tree (Figure 3B) was different from the GPC gene tree with regard to the relationships among groups I, II, III, IV, and V. Specifically, groups II and III were sister to group I in the GPC gene tree whereas groups IV and V were sister to group I in the RdRp gene tree. We note that the probability values in support of the monophyly of groups I, II, and III in the GPC gene tree and the probability values in support of the monophyly of groups I, IV, and V in the RdRp gene tree were ≥ 0.95.

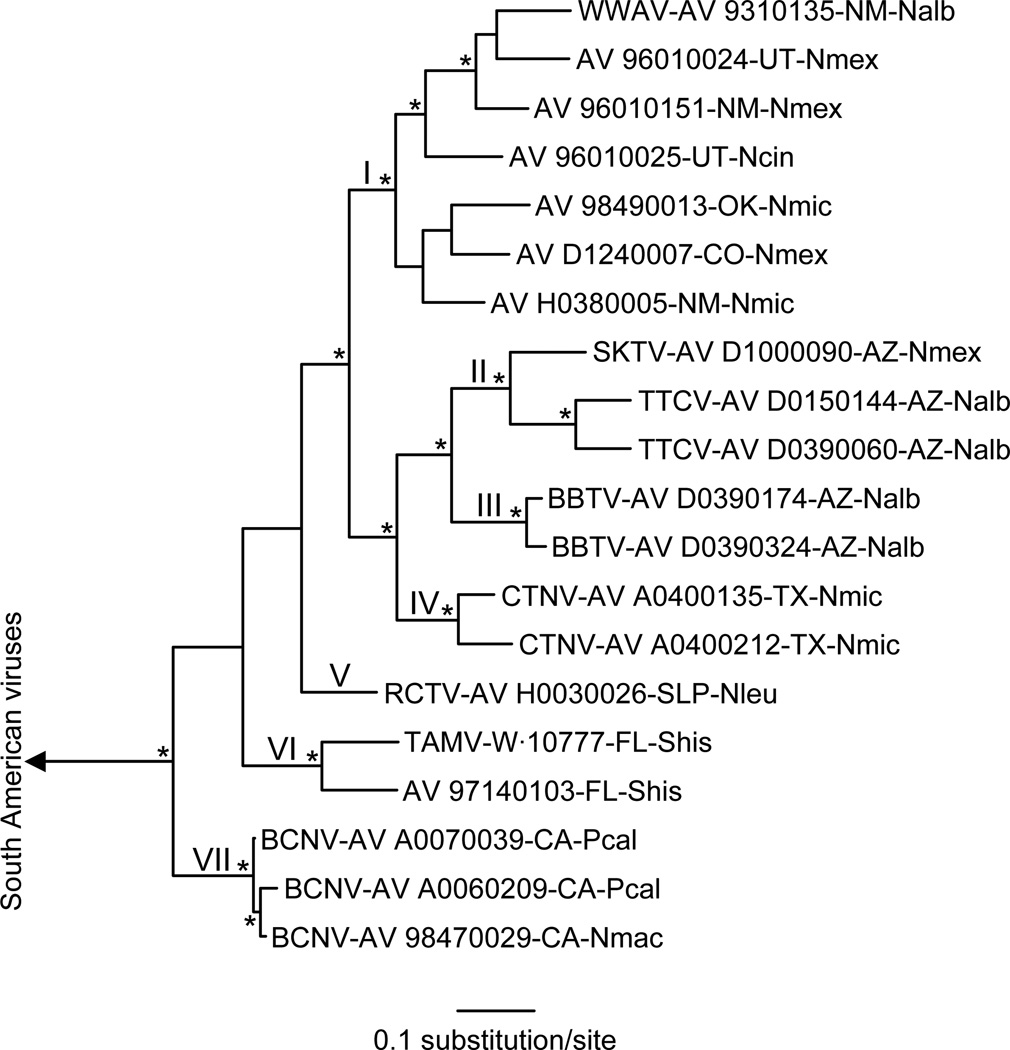

Bayesian analyses of the sequences in a 600-character window of the RdRp gene sequence alignment generated a tree (Figure 4) that was not significantly different from the GPC gene tree (Figure 2A). We note that the 600-character window was flanked by nucleotides 1473 (A) and 2062 (A) in the RdRp gene of WWAV strain AV 9310135 and that each sequence in the 600-character window included at least 1 gap. Finally, bootscan analyses (Martin et al. 2005, Salminen et al. 1995) and analyses done using the Recombination Detection Program (Martin and Rybicki 2000) did not identify any recombination event(s) in the 2253-character RdRp gene sequence alignment that could account for the differences between the tree generated from the RdRp gene sequence data set (Figure 3B) and the GPC and N protein gene trees (Figure 2) with regard to relationships among groups I, II, III, IV, and V.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic relationships among the North American Tacaribe serocomplex viruses based on Bayesian analyses of a 600-character window in the RdRp gene sequence alignment. The length of the scale bar is equivalent to 0.1 substitution per site. Nodal support, Roman numerals, branch labels, and the outgroup in each analysis are as in Figure 2.

Diversity among the GPC and glycoproteins of the North American arenaviruses

The lengths of the GPC of the North American viruses ranged from 480 to 485 aa (Table 3). Nonidentities between the amino acid sequences of the GPC of strains of the same species ranged from 1.4% (BCNV strains AV A0070039 and AV 98470029) to 11.2% (TTCV strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060). Similarly, nonidentity between the sequence of the GPC of AV 97140103 and the sequence of the GPC of TAMV strain W·10777 was 7.4%. Nonidentities among the sequences of the GPC of strains of different species were as high as 41.6% (Table 4). Lastly, nonidentities among the amino acid sequences of the GPC of the 8 viruses in phylogenetic group 1 (i.e., AV 96010024, AV 96010025, AV 96010151, TVP·6038, AV 98490013, AV D1240007, AV H0380005, and WWAV strain AV 9310135) ranged from 1.0 to 25.8% (Table 5).

Table 3.

Lengths of the glycoprotein precursors (GPC), signal peptides (SP), GP1, GP2, nucleocapsid (N) proteins, and Z proteins of the North American Tacaribe serocomplex viruses included in the analyses of amino acid sequence data

| Length of peptide or protein (aa) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speciesa | Strain | GPCb | SP | GP1 | GP2 | N protein | Z protein |

| Bear Canyon virus | AV A0060209 | 483 (RKLQ249) | 58 | 191 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Bear Canyon virus | AV 98470029 | 483 (RKLQ249) | 58 | 191 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Bear Canyon virus | AV A0070039 | 483 (RKLQ249) | 58 | 191 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Bear Canyon virus | AV B0300052 | 483 (RKLQ249) | 58 | 191 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Big Brushy Tank virus | AV D0390174 | 485 (RKPK251) | 58 | 193 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Big Brushy Tank virus | AV D0390324 | 485 (RKPK251) | 58 | 193 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Catarina virus | AV A0400135 | 484 (RKLQ250) | 58 | 192 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Catarina virus | AV A0400212 | 484 (RKLQ250) | 58 | 192 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Real de Catorce virus | AV H0030026 | 483 (RKLL249) | 58 | 191 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Skinner Tank virus | AV D1000090 | 481 (RKLH247) | 58 | 189 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Tamiami virus | W·10777 | 485 (RRIL251) | 58 | 193 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Tamiami virus | AV 97140103 | 485 (RRIL251) | 58 | 193 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Tonto Creek virus | AV D0150144 | 484 (RKLH250) | 58 | 192 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Tonto Creek virus | AV D0390060 | 485 (RKLR251) | 58 | 193 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Whitewater Arroyo virus | AV 9310135 | 480 (RTLK246) | 58 | 188 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV 96010024 | 480 (RSLK246) | 58 | 188 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV 96010025 | 480 (RKLQ246) | 58 | 188 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV 96010151 | 483 (RSLK249) | 58 | 191 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV 98490013 | 482 (RKLQ248) | 58 | 190 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | TVP·6038 | 482 (RKLQ248) | 58 | 190 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV D1240007 | 484 (RKLL250) | 58 | 192 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

| Whitewater Arroyo species complex | AV H0380005 | 484 (RKLQ250) | 58 | 192 | 234 | 562 | 95 |

Big Brushy Tank virus, Catarina virus, Real de Catorce virus, Skinner Tank virus, and Tonto Creek virus are provisional species in the family Arenaviridae.

The tetrapeptide sequence that immediately precedes the putative SKI-1/S1P cleavage site in the GPC is in parentheses.

Table 4.

Nonidentities among the amino acid sequences of the glycoprotein precursors and among the amino acid sequences of the nucleocapsid proteins of the North American Tacaribe serocomplex virusesa

| Glycoprotein precursor (% sequence nonidentity) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus(es)b | BBTV | BCNV | CTNV | RCTV | SKTV | TAMV | TTCV | WWAV |

| BBTV | -- | 34.2--35.1 | 26.7--27.9 | 28.8--29.0 | 25.2--26.8 | 35.5--37.3 | 25.6--26.9 | 30.2--34.0 |

| BCNV | 17.6--18.3 | -- | 35.1--35.8 | 35.1--36.2 | 34.6--35.6 | 32.9--34.2 | 34.4--36.3 | 37.3--41.0 |

| CTNV | 10.1 | 17.3--18.1 | -- | 31.1--31.3 | 29.4--30.2 | 36.2--36.8 | 28.3--31.1 | 31.6--35.4 |

| RCTV | 12.3--12.5 | 17.4--18.0 | 11.2--11.6 | -- | 28.1 | 34.6--34.8 | 29.0--29.6 | 31.4--34.8 |

| SKTV | 10.7--11.0 | 16.9--17.4 | 10.9--11.4 | 13.0 | -- | 33.5--34.5 | 19.5--19.8 | 30.0--33.3 |

| TAMV | 18.5--19.6 | 19.0--21.7 | 17.4--18.5 | 19.8--21.0 | 18.5--19.0 | -- | 34.4--35.8 | 37.5--41.6 |

| TTCV | 10.9--11.4 | 17.1--18.9 | 9.8--11.4 | 12.3--12.5 | 9.4 | 17.6--19.0 | -- | 29.6--33.1 |

| WWAV | 10.7--13.2 | 17.1--21.0 | 11.4--14.6 | 13.7--16.4 | 13.3--15.7 | 18.0--20.8 | 11.9--15.1 | -- |

| Nucleocapsid protein (% sequence nonidentity) | ||||||||

Nonidentities (uncorrected p-model distances) among the amino acid sequences of the glycoprotein precursors (GPC) and among the amino acid sequences of the nucleocapsid (N) proteins are listed above and below the diagonal, respectively.

BBTV, Big Brushy Tank virus strains AV D0390174 and AV D0390324; BCNV, Bear Canyon virus strains AV A0060209, AV A0070039, AV 98470029, and AV B0300052; CTNV, Catarina virus strains AV A0400135 and AV A0400212; SKTV, Skinner Tank virus strain AV D1000090; TAMV, Tamiami virus strains W·10777 and AV 97140103; TTCV, Tonto Creek virus strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060; WWAV, Whitewater Arroyo species complex---Whitewater Arroyo virus prototype strain AV 9310135 and viruses AV 96010024, AV 96010025, AV 96010151, TVP·6038, AV 98490013, AV D1240007, and AV H0380005. Nonidentities between the sequences of the GPC of strains of the same species ranged from 1.4% (BCNV strains AV A0070039 and AV 98470029) to 11.2% (TTCV strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060), nonidentities between the sequences of the N proteins of strains of the same species ranged from 0.4% (BCNV strains AV A0070039 and AV 98470029) to 5.7% (BCNV strains AV A0070039 and AV B0300052), and nonidentities between the sequences of the GPC and between the sequences of the N proteins of the 8 viruses included in the Whitewater Arroyo species complex ranged from 1.0% (TVP·6038 and AV 98490013) to 25.8% (AV 96010024 and AV D1240007) and from 0.2% (TVP·6038 and AV 98490013) to 10.5% (AV 96010024 and AV 96010025), respectively.

Table 5.

Nonidentities among the amino acid sequences of the glycoprotein precursors and among the amino acid sequences of the nucleocapsid proteins of the Whitewater Arroyo species complex virusesa

| Glycoprotein precursor (% sequence nonidentity) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | AV 93 10135 |

AV 96 010024 |

AV 96 010025 |

AV 96 010151 |

AV 98 490013 |

TVP· 6038 |

AV D1 240007 |

AV H0 380005 |

| AV 9310135 | -- | 19.8 | 21.5 | 19.2 | 22.8 | 22.8 | 25.6 | 25.2 |

| AV 96010024 | 9.3 | -- | 19.8 | 16.0 | 22.4 | 22.2 | 25.8 | 24.2 |

| AV 96010025 | 10.0 | 10.5 | -- | 19.8 | 22.8 | 22.6 | 24.6 | 24.8 |

| AV 96010151 | 6.2 | 7.3 | 8.2 | -- | 22.7 | 22.7 | 25.5 | 22.8 |

| AV 98490013 | 9.3 | 10.0 | 8.9 | 7.8 | -- | 1.0 | 18.5 | 22.0 |

| TVP·6038 | 9.1 | 10.1 | 8.7 | 7.7 | 0.2 | -- | 18.7 | 21.8 |

| AV D1240007 | 9.1 | 10.3 | 8.4 | 7.3 | 6.9 | 7.1 | -- | 23.6 |

| AV H0380005 | 9.1 | 9.8 | 8.4 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 7.5 | -- |

| Nucleocapsid protein (% sequence nonidentity) | ||||||||

Nonidentities (p-model distances) among the amino acid sequences of the glycoprotein precursors and among the amino acid sequences of the nucleocapsid proteins are listed above and below the diagonal, respectively.

Maturation of the arenavirus glycoproteins entails proteolytic cleavage of the GPC. Co-translational cleavage by a cellular signal peptidase yields a signal peptide (SP) and GP1-GP2 polypeptide (Eichler et al. 2003); post-translational cleavage of the GP1-GP2 polypeptide by a cellular SKI-1/S1P protease yields the amino-terminal GP1 and carboxy-terminal GP2 (Beyer et al. 2003; Lenz et al. 2000, 2001; Rojek et al. 2008). The GPC of each North American virus in this study contained a potential signal peptidase cleavage site after residue 58 (SCS58↓) and a potential SKI-1/S1P cleavage site within the region flanked by residues 246 and 252 (Table 3). Accordingly, the lengths of the GP1 of the North American viruses ranged from 188 to 193 aa (Table 3).

In pairwise comparisons, the prevalence of nonconservative differences and conservative differences between the amino acid sequences of the GP1 of strains of the same species ranged from 0/191 (BCNV strains AV A0060209, AV A0070039, and AV 98470029) to 5/193 (BBTV strains AV D0390174 and AV D0390324) and from 2/191 (BCNV strains AV A0060209 and AV 98470029) to 36/193 (TTCV virus strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060), respectively. Similarly, the prevalence of nonconservative differences and conservative differences among the amino acid sequences of the GP1 of the 8 viruses in phylogenetic group I ranged from 0/190 to 17/191 and from 4/190 to 75/192, respectively (Table 6).

Table 6.

Prevalence of nonconservative and conservative differences among the amino acid sequences of the GP1 (glycoproteins) of the Whitewater Arroyo species complex virusesa

| Prevalence of nonconservative differences |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | AV 93 10135 |

AV 96 010024 |

AV 96 010025 |

AV 96 010151 |

AV 98 490013 |

TVP· 6038 |

AV D1 240007 |

AV H0 380005 |

| AV 9310135 | -- | 8/188 | 6/188 | 6/191 | 13/191 | 14/191 | 14/192 | 9/192 |

| AV 96010024 | 55/188 | -- | 10/188 | 7/191 | 16/191 | 17/191 | 15/192 | 9/192 |

| AV 96010025 | 58/188 | 52/188 | -- | 10/191 | 15/191 | 16/191 | 13/192 | 10/192 |

| AV 96010151 | 53/191 | 45/191 | 51/191 | -- | 9/191 | 9/191 | 10/192 | 7/192 |

| AV 98490013 | 62/191 | 66/191 | 62/191 | 68/191 | -- | 0/190 | 13/192 | 7/191 |

| TVP·6038 | 62/191 | 67/191 | 63/191 | 70/191 | 4/190 | -- | 12/192 | 8/192 |

| AV D1240007 | 69/192 | 75/192 | 67/192 | 71/192 | 44/192 | 47/192 | -- | 9/192 |

| AV H0380005 | 73/192 | 71/192 | 70/192 | 68/192 | 63/191 | 62/192 | 67/192 | -- |

| Prevalence of conservative differences | ||||||||

Prevalence of nonconservative and conservative differences are listed above and below the diagonal, respectively.

Diversity among the N proteins of the North American arenaviruses

The lengths of the N proteins of the North American viruses were identical (i.e., 562 aa). Nonidentities between the amino acid sequences of the N proteins of strains of the same species ranged from 0.4% (BCNV strains AV A0070039 and AV 98470029) to 5.7% (BCNV strains AV A0070039 and AV B0300052). Similarly, nonidentity between the sequence of the N protein of AV 97140103 and the sequence of the N protein of TAMV strain W·10777 was 5.0%. Nonidentities among the sequences of the N proteins of strains of different North American species were as high as 21.7% (Table 4). Lastly, nonidentities among the amino acid sequences of the N proteins of the 8 viruses in phylogenetic group I ranged from 0.2 to 10.5% (Table 5).

Diversity among the Z proteins and among the RNA-dependent polymerases of the North American arenaviruses

The lengths of the Z proteins of the North American viruses were identical (i.e., 95 aa). Nonidentities between the amino acid sequences of the Z proteins and between the amino acid sequences of the RdRp of strains of the same species ranged from 1.1% (BCNV strains AV A0060209 and AV A0070039, and CTNV strains AV A0400135 and AV A0400212) to 3.2% (BBTV strains AV D0390174 and AV D0390324, BCNV strains AVA0060209 and AV 98470209, and TTCV strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060) and from 1.0% (BCNV strains AV A0070039 and AV 98470029) to 10.6% (TTCV strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060), respectively. Nonidentities between the sequences of the Z proteins and between the sequences of the RdRp of AV 97140103 and TAMV strain W·10777 were 2.1% and 12.0%, respectively. Nonidentities among the sequences of the Z proteins and among the sequences of the RdRp of strains of different North American species were as high as 23.2% (BCNV strain AV 98470029 and TAMV strain W·10777) and 36.7% (BBTV strain AV D0390174 and BCNV strain AV98470029), respectively. Finally, nonidentities among the amino acid sequences of the Z proteins and among the amino acid sequences of the RdRp of the viruses in phylogenetic group I ranged from 0.0% (AV 96010151 and WWAV strain AV 9310135) to 7.4% (AV 98490013 and AV H0380005) and from 12.0% (AV 98490013 and AV D1240007) to 18.2% (AV 96010024 and AV 98490013), respectively.

Discussion

As indicated previously, the RdRp gene tree generated from the 2253-character RdRp gene sequence data set (Figure 3B) was substantively different from the GPC gene tree (Figure 2A) with regard to the relationships among groups I, II, III, IV, and V. This difference in tree topology may be evidence of genetic reassortment or genetic recombination between arenaviruses with different phylogenetic histories. Alternatively, the difference between the RdRp and GPC gene trees may be a consequence of using a model of DNA evolution rather than a model of RNA evolution, incongruence among the gene tree data sets, or chance. We note that the results of neighbor-joining and parsimony analyses of the RdRp gene data set were not markedly different from the results of the Bayesian analyses of the GPC gene data set with regard to relationships among phylogenetic groups I, II, III, IV, and V.

The topology of the tree generated from the sequences in the 600-character window in the RdRp gene sequence alignment (Figure 4) was not markedly different from the topology of the GPC gene tree. Further, the bootscan analysis of the 2253-character RdRp gene sequence alignment did not reveal any recombination event(s) that could account for the difference between the RdRp gene tree in Figure 3B and GPC gene tree with regard to the relationships among phylogenetic groups I, II, III, IV, and V. Collectively, the results of the Bayesian analyses of the 600-character window and the results of the bootscan analysis indicate that the difference between the RdRp gene tree in Figure 3B and the GPC gene tree was not a consequence of genetic reassortment or genetic recombination.

The Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (Salvato et al. 2005) indicated that different arenavirus species should occupy different ecological niches and that strains of different arenavirus species should exhibit significant differences from one another in comparisons of amino acid sequences and in reciprocal (two-way) serological tests. We note that nonidentities between the complete sequences of the GPC and between the complete sequences of the N proteins of strains of different South American arenavirus species in a previously published study were as low as 15.8% and 11.9%, respectively (Milazzo et al. 2008).

Previous studies established that the southern plains woodrat (N. micropus) in southern Texas is the principal host of CTNV (Cajimat et al. 2007a, Fulhorst et al. 2002b) and that the hispid cotton rat (S. hispidus) in southern Florida is the principal host of TAMV (Bigler et al. 1975, Calisher et al. 1970, Jennings et al. 1970). In this study, nonidentities between the sequences of the GPC and between the sequences of the N proteins of AV 97140103 and TAMV strain W·10777 were 7.4% and 5.0%, respectively. Collectively, the isolation of AV 97140103 from hispid cotton rat FSH33, the results of the Bayesian analyses of nucleotide sequences, and the low level of amino acid sequence nonidentity between the GPC and between the N proteins of AV 97140103 and TAMV strain W·10777 indicate that AV 97140103 is a strain of TAMV, despite the high level (12.0%) sequence nonidentity between the RdRp of strains AV 97140103 and W·10777.

Specific knowledge of the natural host relationships of the North American arenaviruses other than CTNV and TAMV is limited to the results of assays for arenavirus or arenaviral RNA in tissues from a small number of wild-caught rodents. For example, WWAV---isolation of virus from 2 of 16 woodrats (presumed to be N. albigula) captured in 1993 in northwestern New Mexico (Fulhorst et al. 1996); BBTV---isolation of virus from 15 of 42 white-throated woodrats (N. albigula) captured in February 2002 in eastern Arizona (Milazzo et al. 2008); SKTV---isolation of virus from 4 of 32 Mexican woodrats (N. mexicana) captured in August 2002 at a locality in northern Arizona (Cajimat et al. 2008); and RCTV---detection of RCTV RNA in 2 of 9 white-toothed woodrats (N. leucodon) captured in August 2005 at a locality in northern San Luis Potosí (Inizan et al. 2010). Relatively few of the other rodents captured at these localities were tested for arenavirus or arenaviral RNA. Clearly, the ecologies (principal host relationships) of many of the North American viruses in this study have not been well defined.

Nonidentities among the GPC sequences and among the N protein sequences of the 8 viruses in phylogenetic group I were as high as 25.8% (AV D1240007 and AV 96010024) and 10.5% (AV 96010024 and AV 96010025), respectively (Table 5). Conceptually, some of the viruses in group I may be strains of species other than WWAV.

Our knowledge of the serological relationships among the North American arenaviruses is limited to the TAMV prototype strain W·10777 and WWAV prototype strain AV 9310135. The results of two-way plaque-reduction neutralization tests indicated that these strains represent different serotypes (Fulhorst et al. 1996).

Previous studies established that the dominant neutralizing epitopes on an arenavirion are associated with GP1 (Buchmeier et al. 1981) and that antibody-mediated neutralization in vitro usually is specific to an arenavirus species (Sanchez et al. 1989, Tesh et al. 1994). The high prevalence of nonconservative differences between the primary structures of the GP1 of AV 98490013 (or TVP·6038), AV D1240007, and AV H0380005 and the primary structure of the GP1 of WWAV strain AV 9310135 supports the notion that some of the viruses in group I in the GPC tree (Figure 2A) are strains of species other than WWAV. Pending the results of studies to define the serological relationships among the viruses in group I and studies to define better the ecologies of these viruses, we recommend that AV 96010025, AV 98490013, TVP·6038, and AV H0380005 be included with AV 96010024, AV 96010151, AV D1240007, and WWAV strain AV 9310135 in the Whitewater Arroyo species complex (Cajimat et al. 2008).

As stated previously, the results of a recently published study (Milazzo et al. 2011) indicated that WWAV or viruses antigenically closely related to the WWAV prototype strain AV 9310135 naturally cause acute central nervous system disease or undifferentiated febrile illnesses in humans. The nucleotide sequences of the North American viruses included in the data analyses in this study may prove useful in the development of accurate assays for arenaviral RNA in acute-phase clinical specimens from febrile persons infected with North American Tacaribe serocomplex viruses.

Materials and Methods

Total RNA was isolated from a sample of kidney from white-toothed woodrat (N. leucodon) TK133448 and from monolayers of infected Vero E6 cells, using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc., Carlsbad, CA). All work with infectious materials was done inside a biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) laboratory.

First-strand cDNA was synthesized by using SuperScript III RNase H− Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc.) in conjunction with oligonucleotide 19C–cons (Cajimat et al. 2007b). This oligonucleotide was expected to prime synthesis of cDNA from 4 different templates: L segment, replicative intermediate of the L segment, S segment, replicative intermediate of the S segment (Cajimat et al. 2007b). Amplicons were generated from first-strand cDNA by using the Master Taq Kit (Eppendorf North America, Inc., Westbury, NY) and strategies published previously (Fulhorst et al. 2008). Both strands of each amplicon were sequenced directly, using the dye termination cycle sequencing technique (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA). Sequence Rx Enhancer Solution A (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc.) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was included in some sequencing reactions to improve the quality of the sequence data.

The analyses of nucleotide sequence data included Allpahuayo virus strain CLHP-2472 (GenBank Accession Nos. AY012687 and AY216502), Amaparí virus strain BeAn 70563 (AF512834 and AY924389), CHPV strain 200001071 (EU260463 and EU260464), Cupixi virus strain BeAn 119303 (AF512832 and AY216519), Flexal virus strain BeAn 293022 (AF512831 and EU627611), GTOV strain INH-95551 (AY129247 and AY358024), JUNV strain XJ13 (AY358023 and AY358022), Latino virus strain MARU 10924 (AF512830, AY960333, and AY935533), MACV strain Carvallo (AY129248 and AY358021), Oliveros virus strain 3229-1 (U34248 and AY211514), Paraná virus strain 12056 (AF485261 and EU627613), Pichindé virus strain Co An 3739 (K02734 and AF427517), Pirital virus strain VAV-488 (AF485262 and AY494081), SABV strain SPH 114202 (U41071 and AY358026), and TCRV strain TRVL 11573 (M20304 and J04340). The sequences in each amino acid sequence data set were aligned by using the computer program Clustal W (2.0.12) (Thompson et al. 1994); the sequences in each nucleotide sequence data set were aligned manually, with the alignment guided by the corresponding computer-generated amino acid sequence alignment; sequence nonidentities were equivalent to uncorrected (p) distances; and the pairwise comparisons of conspecific strains included BBTV strains AV D0390174 and AV D0390324, BCNV strains AV A0060209, AV A0070039, AV B0300052, and AV 98470029, CTNV strains AV A0400135 and AV A0400212, and TTCV strains AV D0150144 and AV D0390060.

The phylogenetic analyses of nucleotide sequences were done with MRBAYES 3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001) and programs in the computer software package PAUP* (Swofford 2002). The Bayesian analyses used a GTR+I+G model with a site-specific gamma distribution and the following options in MRBAYES 3.1.2: two simultaneous runs of 4 Markov chains, two million (2,000,000) generations, and sample frequency = every 1,000th generation.1 The first 1,000 trees were discarded after review of the likelihood scores, convergence statistics, and potential scale reduction factors; and a consensus tree (50% majority rule) was constructed from the remaining trees. We note that the average standard deviation of split frequencies in each analysis was < 0.01 at burn-in (1,000,000 generations) and < 0.01 at 2,000,000 generations; probability values in support of the clades were calculated a posteriori; and clades with probability values ≥ 0.95 were considered supported by the data (Erixon et al. 2003).

BOOTSCAN (Martin et al. 2005, Salminen et al. 1995) and the Recombination Detection Program (Martin and Rybicki 2000) in Recombination Detection Program, version 3 (RDP3) (Martin et al. 2010) were used to examine the 2253-character RdRp gene sequence alignment for evidence of genetic recombination. BOOTSCAN was set to sliding windows of 300, 600, and 900 characters in steps of 150, 300, and 450, respectively. The bootscan analysis was done with RCTV strain AV H0030026 as the query and then with the exploratory option. The Recombination Detection Program analysis used the default settings in RDP3 and then with the window size set from 60 to 300 characters in steps of 30.

Differences between the amino acid sequences of the GP1 of strains of the same species and differences among the amino acid sequences of the GP1 of the 8 viruses in phylogenetic group I (Figure 2A) were scored favored, neutral, or disfavored, using substitution preferences for extracellular proteins (Betts and Russell 2003). Favored and neutral differences were considered conservative; disfavored differences and gaps in the alignments were considered nonconservative.

The species identities of 20 of the 22 virus-positive rodents in this study were confirmed by analyses of cytochrome-b (Cytb) gene sequences (Appendix 1). The exceptions were the WWAV-infected woodrat captured in McKinley County, New Mexico, and the TAMV-infected hispid cotton rat captured in Hendry County, Florida. Tissues from these 2 rodents could not be located for this study. We note that woodrats TK28731 (N. micropus) and TK28742 (N. leucodon) were mistakenly identified as white-throated woodrats (N. albigula) in a previous study in which species identities were based solely on external morphological features of the voucher specimens (Fulhorst et al. 2001).

Appendix 1.

Geographical coordinates of the localities at which the arenavirus-positive rodents were captured

| Rodent No. | Speciesa | GenBank Accession No.b |

Statec | County or Municipality |

Localityd | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TK91001 | Nmac | FJ744107 | CA | Los Angeles | Zuma Canyon (1) | 34°0’56”N, 118°49’8”W |

| TK90599 | Pcal | FJ716218 | CA | Orange | El Cariso (2) | 33°39’48”N, 117°25’42”W |

| TK83707 | Nmac | AF376479 | CA | Riverside | Lake Elsinore (3) | 33°36’55”N, 117°21’13”W |

| TK90438 | Pcal | FJ716219 | CA | Riverside | Bear Canyon (4) | 33°36’42”N, 117°25’30”W |

| 36287 | Ncin | AF186799 | UT | San Juan | NBNM (5) | 37°34’59”N, 110°0’47”W |

| 36282 | Nmex | AF298841 | UT | San Juan | NBNM (5) | 37°35’50”N, 109°56’0”W |

| TK123380 | Nmex | FJ716223 | CO | Larimer | Big Thompson Canyon (9) | 40°25’17”N, 105°13’31”W |

| TK119202 | Nmex | FJ716222 | AZ | Coconino | Skinner Tank (6) | 35°55’16”N, 112°0’39”W |

| TK93637 | Nalb | EU141961 | AZ | Gila | White Cow Mine (7) | 33°53’49”N, 111°16’57”W |

| TK113981 | Nalb | EU141963 | AZ | Gila | Cherry Creek (7) | 33°45’49”N, 110°48’47”W |

| TK114533 | Nalb | EU141960 | AZ | Graham | Brushy Tank (8) | 32°22’23”N, 110°18’55”W |

| TK114581 | Nalb | EU141964 | AZ | Graham | Hackberry Creek (8) | 33°23’22”N, 110°21’30”N |

| 1627 | Nalb | -- | NM | McKinley | Whitewater Arroyo (10) | 35°16’35”N, 108°58’52”W |

| 62425 | Nmex | AF298847 | NM | Socorro | Magdalena Mountains (11) | 33°59’25”N, 107°10’51”W |

| TK77260 | Nmic | AF376473 | NM | Otero | Fort Bliss (12) | 32°27’46”N, 105°49’66”W |

| TK28731 | Nmic | FJ716217 | OK | Cimarron | Black Mesa (13) | 36°52’50”N, 102°55’28”W |

| TK28742 | Nleu | AF186815 | OK | Cimarron | Black Mesa (13) | 36°52’50”N, 102°55’28”W |

| TK84703 | Nmic | FJ716220 | TX | Dimmit | CWMA (14) | 28°19’24”N, 99°24’20”W |

| TK84816 | Nmic | FJ716221 | TX | La Salle | CWMA (14) | 28°18”46”N, 99°21’47”W |

| FSH33 | Shis | AF155420 | FL | Miami-Dade | Homestead Air Force Base (17) | 25°29’42”N, 80°23’38”W |

| (none) | Shis | -- | FL | Hendry County | Everglades National Park (16) | 26°17’N, 81°5’W |

| TK133448 | Nleu | GU220381 | SLP | Catorce | Real de Catorce (15) | 23°49’5”N, 100°49’54”W |

Nalb, Neotoma albigula; Ncin, N. cinerea; Nleu, N. leucodon; Nmex, N. mexicana; Nmac, N. macrotis; Nmic, N. micropus; Pcal, Peromyscus californicus; Shis, Sigmodon hispidus.

Accession numbers of the cytochrome-b gene sequences. The nucleotide sequences of the cytochrome-b genes of woodrat 1627 and the cotton rat captured in Hendry County were not determined because tissues from these rodents could not be located.

AZ, Arizona; CA, California; CO, Colorado; FL, Florida; NM, New Mexico; OK, Oklahoma; SLP, San Luis Potosí; TX, Texas; UT, Utah.

CWMA, Chaparral Wildlife Management Area; NBNM, Natural Bridges National Monument. The numbers in parentheses indicate the positions of the localities on the map in Figure 1.

Acknowledgments

Mary Louise Milazzo and Maria N. B. Cajimat contributed equally to this study. Duke S. Rogers (Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah) provided many helpful comments related to the interpretation of the results of the phylogenetic analyses. Patricia Repik (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) facilitated administration of the grant support for this study.

Financial support

National Institutes of Health grants AI-41435 and AI-67947 provided the financial support for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

MODELTEST (Posada and Crandall 1998) was used to determine which of 56 maximum likelihood models of DNA evolution best fit each data set. The GTR+I+G model best fit the GPC, N protein, and RdRp gene data sets, and the K81uf +I + G model best fit the Z gene data set. The K81uf +I + G model was not supported by MRBAYES 3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001); consequently, the GTR+I+G model was used in the analyses of the Z gene sequence data as well as the analyses of the GPC, N protein, and RdRp gene sequence data.

Contributor Information

Maria N. B. Cajimat, Email: nbcajirm@utmb.edu.

Mary Louise Milazzo, Email: mamilazz@utmb.edu.

Michelle L. Haynie, Email: mhaynie@uco.edu.

J. Delton Hanson, Email: j.delton.hanson@gmail.com.

Robert D. Bradley, Email: robert.bradley@ttu.edu.

Charles F. Fulhorst, Email: cfulhors@utmb.edu.

References

- Betts MJ, Russell RB. Amino acid properties and consequences of substitutions. In: Barnes MR, Gray IC, editors. Bioinformatics for Geneticists. Wiley; 2003. pp. 290–316. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer WR, Pöpplau D, Garten W, von Laer D, Lenz O. Endoproteolytic processing of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein by the subtilase SKI-1/S1P. J. Virol. 2003;77:2866–2872. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.5.2866-2872.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler WJ, Lassing E, Buff E, Lewis AL, Hoff GL. Arbovirus surveillance in Florida: wild vertebrate studies 1965–1974. J. Wildl. Dis. 1975;11:348–356. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-11.3.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier MJ, Lewicki HA, Tomori O, Oldstone MBA. Monoclonal antibodies to lymphocytic choriomeningitis and Pichinde viruses: generation, characterization, and cross-reactivity with other arenaviruses. Virology. 1981;113:73–85. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajimat MNB, Milazzo ML, Bradley RD, Fulhorst CF. Catarina virus, an arenaviral species principally associated with Neotoma micropus (southern plains woodrat) in Texas. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007a;77:732–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajimat MNB, Milazzo ML, Hess BD, Rood MP, Fulhorst CF. Principal host relationships and evolutionary history of the North American arenaviruses. Virology. 2007b;367:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajimat MNB, Milazzo ML, Borchert JN, Abbott KD, Bradley RD, Fulhorst CF. Diversity among Tacaribe serocomplex viruses (family Arenaviridae) naturally associated with the Mexican woodrat (Neotoma mexicana) Virus Res. 2008;133:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calisher CH, Tzianabos T, Lord RD, Coleman PH. Tamiami virus, a new member of the Tacaribe group. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1970;19:520–526. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado S, Erickson BR, Agudo R, Blair PJ, Vallejo E, Albariño CG, Vargas J, Comer JA, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Olson JG, Nichol ST. Chapare virus, a newly discovered arenavirus isolated from a fatal hemorrhagic fever case in Bolivia. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000047. (e1000047). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler R, Lenz O, Strecker T, Garten W. Signal peptide of Lassa virus glycoprotein GP-C exhibits an unusual length. FEBS Lett. 2003;538:203–206. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erixon P, Svennblad B, Britton T, Oxelman B. Reliability of Bayesian posterior probabilities and bootstrap frequencies in phylogenetics. Syst. Biol. 2003;52:665–673. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulhorst CF, Bowen MD, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Nichol ST, Kosoy MY, Peters CJ. Isolation and characterization of Whitewater Arroyo virus, a novel North American arenavirus. Virology. 1996;224:114–120. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulhorst CF, Bowen MD, Salas RA, de Manzione NMC, Duno G, Utrera A, Ksiazek TG, Peters CJ, Nichol ST, de Miller E, Tovar D, Ramos B, Vasquez C, Tesh RB. Isolation and characterization of Pirital virus, a newly discovered South American arenavirus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1997;56:548–553. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulhorst CF, Bowen MD, Salas RA, Duno G, Utrera A, Ksiazek TG, de Manzione NMC, de Miller E, Vasquez C, Peters CJ, Tesh RB. Natural rodent host associations of Guanarito and Pirital viruses (family Arenaviridae) in central Venezuela. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999;61:325–330. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulhorst CF, Charrel RN, Weaver SC, Ksiazek TG, Bradley RD, Milazzo ML, Tesh RB, Bowen MD. Geographic distribution and genetic diversity of Whitewater Arroyo virus in the southwestern United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001;7:403–407. doi: 10.3201/eid0703.010306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulhorst CF, Bennett SG, Milazzo ML, Murray HL, Jr., Webb JP, Jr., Cajimat MNB, Bradley RD. Bear Canyon virus: an arenavirus naturally associated with the California mouse (Peromyscus californicus) Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002a;8:717–720. doi: 10.3201/eid0807.010281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulhorst CF, Milazzo ML, Carroll DS, Charrel RN, Bradley RD. Natural host relationships and genetic diversity of Whitewater Arroyo virus in southern Texas. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002b;67:114–118. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulhorst CF, Cajimat MNB, Milazzo ML, Paredes H, de Manzione NMC, Salas RA, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG. Genetic diversity between and within the arenavirus species indigenous to western Venezuela. Virology. 2008;378:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist FR. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Biometrics. 2001;17:754–756. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inizan CC, Cajimat MNB, Milazzo ML, Barragán-Gomez A, Bradley RD, Fulhorst CF. Genetic evidence for a Tacaribe serocomplex virus, Mexico. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;16:1007–1010. doi: 10.3201/eid1606.091648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings WL, Lewis AL, Sather GE, Pierce LV, Bond JO. Tamiami virus in the Tampa Bay area. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1970;19:527–536. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz O, ter Meulen J, Feldmann H, Klenk H-D, Garten W. Identification of a novel consensus sequence at the cleavage site of the Lassa virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 2000;74:11418–11421. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11418-11421.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz O, ter Meulen J, Klenk H-D, Seidah NG, Garten W. The Lassa virus glycoprotein precursor GP-C is proteolytically processed by subtilase SKI-1/S1P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:12701–12705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221447598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D, Rybicki E. RDP: detection of recombination amongst aligned sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:562–563. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Posada D, Crandall KA, Williamson C. A modified bootscan algorithm for automated identification of recombinant sequences and recombination breakpoints. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2005;21:98–102. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Lemey P, Lott M, Moulton V, Posada D, Lefeuvre P. RDP3: a flexible and fast computer program for analyzing recombination. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2462–2463. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milazzo ML, Cajimat MNB, Haynie ML, Abbott KD, Bradley RD, Fulhorst CF. Diversity among Tacaribe serocomplex viruses (family Arenaviridae) naturally associated with the white-throated woodrat (Neotoma albigula) in the southwestern United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:523–540. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milazzo ML, Barragán-Gomez A, Hanson JD, Estrada-Franco JG, Arellano E, González-Cózatl FX, Fernández-Salas I, Ramirez-Aguilar F, Rogers DS, Bradley RD, Fulhorst CF. Antibodies to Tacaribe serocomplex viruses (family Arenaviridae, genus Arenavirus) in cricetid rodents from New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:629–637. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milazzo ML, Campbell GL, Fulhorst CF. Novel arenavirus infection in humans, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:1417–1420. doi: 10.3201/eid1708.110285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JN, Ellis BA, McKee KT, Jr, Calderon GE, Maiztegui JI, Nelson GO, Ksiazek TG, Peters CJ, Childs JE. A longitudinal study of Junin virus activity in the rodent reservoir of Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1992;47:749–763. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser GG, Carleton MD. Superfamily Muroidea. In: Wilson DE, Reeder DM, editors. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. third ed. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. pp. 894–1531. [Google Scholar]

- Peters CJ. Human infection with arenaviruses in the Americas. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002;262:65–74. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56029-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojek JM, Lee AM, Nguyen N, Spiropoulou CF, Kunz S. Site 1 protease is required for proteolytic processing of the glycoproteins of the South American hemorrhagic fever viruses Junin, Machupo, and Guanarito. J. Virol. 2008;82:6045–6051. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02392-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen MO, Carr JK, Buke DS, McCutchan FE. Identification of breakpoints in intergenotypic recombinants of HIV type 1 by BOOTSCANning. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruse. 1995;11:1423–1425. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvato MS, Clegg JCS, Buchmeier MJ, Charrel RN, Gonzalez J-P, Lukashevich IS, Peters CJ, Rico-Hesse R, Romanowski V. Family Arenaviridae. In: Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA, editors. Virus Taxonomy: Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. pp. 725–733. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez A, Pifat DY, Kenyon RH, Peters CJ, McCormick JB, Kiley MP. Junin virus monoclonal antibodies: characterization and cross-reactivity with other arenaviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 1989;70:1125–1132. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-5-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (* and other methods), version 4.0b10. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc., Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tesh RB, Jahrling PB, Salas R, Shope RE. Description of Guanarito virus (Arenaviridae: Arenavirus), the etiologic agent of Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1994;50:452–459. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W (1.7): improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choices. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]