Abstract

Background

To review our experience of gastroduodenal tuberculosis before formulating management guidelines, we did a retrospective analysis at a large tertiary-care teaching institution in North India.

Method

We reviewed 23 consecutive cases of biopsy-proven gastroduodenal tuberculosis over a period of 15 years.

Results

The major presenting features were gastric outlet obstruction (61%) and upper gastrointestinal (uGI) bleeding (26%). In 3 patients (13%), clinical, radiological and intraoperative features suggested malignancy/pseudotumour: periampullary mass in 2 and gastric mass in 1 patient. Five patients (23%) also had extragastrointestinal tuberculosis. Despite uGI endoscopy and biopsies, the preoperative diagnosis was correct for only 2 people. All patients except 1 required surgery for either diagnosis or therapy. Two patients with massive uGI hemorrhage requiring emergency surgery died in the postoperative period. The other patients responded well to antitubercular treatment after surgery.

Conclusions

Gastroduodenal tuberculosis has 3 forms of presentation: obstruction, uGI bleeding, and gastric or periampullary mass suggestive of malignancy. Endoscopic biopsy has a poor yield. Surgery is usually required for diagnosis or therapy, after which patients respond well to antituberculous treatment. In areas endemic for tuberculosis, a good biopsy from the site of gastroduodenal bleeding or mass lesion and the surrounding lymph nodes should always be obtained.

Abstract

Contexte

Pour revoir notre expérience de la tuberculose gastroduodénale avant de formuler des lignes directrices sur le traitement, nous avons procédé à une analyse rétrospective à un important établissement d'enseignement de soins tertiaires dans le nord de l'Inde.

Méthode

Nous avons étudié 23 cas consécutifs de tuberculose gastroduodénale prouvée par biopsie sur une période de 15 ans.

Résultats

La sténose du défilé gastrique (61 %) et le saignement gastro-intestinal supérieur (GIs) (26 %) ont constitué les principales caractéristiques au moment de la présentation. Chez trois patients (13 %), les caractéristiques cliniques, radiologiques et intraopératoires ont indiqué la présence d'une tumeur maligne-pseudotumeur : masse périampullaire dans deux cas et masse gastrique chez un autre patient. Cinq patients (23 %) avaient aussi une tuberculose extragastro-intestinale. En dépit d'une endoscopie GIs et de biopsies, le diagnostic préopératoire était exact dans deux cas seulement. Tous les patients sauf un ont eu besoin d'une intervention chirurgicale diagnostique ou thérapeutique. Deux patients qui avaient une hémorragie GIs massive qui a obligé à pratiquer une intervention chirurgicale d'urgence sont morts après l'intervention. Les autres patients ont bien répondu au traitement antituberculeux après l'intervention chirurgicale.

Conclusions

La tuberculose gastroduodénale se manifeste de trois façons : occlusion, saignement GIs et présence d'une masse gastrique ou périampullaire indiquant la présence d'une tumeur maligne. La biopsie endoscopique produit des résultats médiocres. Il faut habituellement pratiquer une intervention chirurgicale diagnostique ou thérapeutique après laquelle les patients répondent bien au traitement antituberculeux. Dans les régions où la tuberculose est endémique, il faut toujours pratiquer une bonne biopsie du point de saignement gastroduodénal ou de la tumeur ainsi que des ganglions lymphatiques voisins.

Tuberculosis (TB) is endemic in India. In the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the ileocecal region is the predominant site of involvement.1 Possibly because tubercular involvement of the gastroduodenal (GD) region is rare,2,3 it is often misdiagnosed and treated as peptic ulcer disease, even where it is endemic.

Since GD TB exhibits no specific symptoms or signs and no characteristic endoscopic or radiographic features, diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion. The paucity of information about its presentation and management prompted us to review and present our experience with 23 such cases along with a review of the literature, and to suggest management guidelines.

Method

All 23 consecutive patients with histologically proven GD TB who were treated at the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi from January 1986 through July 2000 were reviewed retrospectively. The diagnosis of TB was based on histopathology showing caseating epithelioid-cell granulomas. (Acid-fast bacilli as revealed by Ziehl – Neelsen stain were seen in only 6 cases.) Data noted for analysis included age, sex, presenting symptoms and their duration, treatment(s) and outcome.

Results

The mean age of the 23 qualifying patients was 34.4 years (range 15– 62 yr). The 17 men and 6 women yielded a gender ratio of 2.8:1.

Presenting symptoms and signs

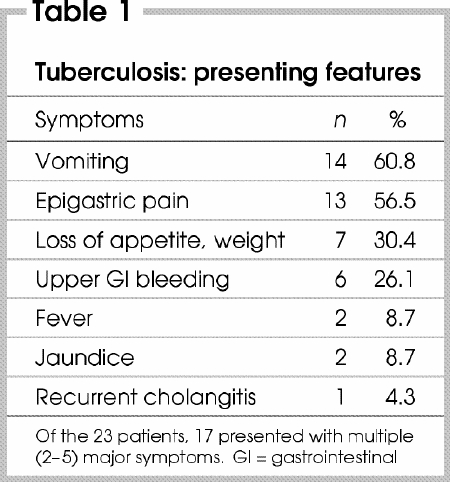

Duration of symptoms varied from 2 days to 15 years; the main presenting symptoms are shown in Table 1. Fourteen patients (61%) arrived with features of gastric-outlet obstruction. Six patients (26%) had upper-GI hemorrhage, 3 with massive bleeding requiring emergency surgery. Three patients (13%) had clinical features suggestive of malignancy. None presented with perforation of the stomach or duodenum.

Table 1

Five patients (23%) also had extraGI TB: 2 had an active pulmonary lesion with acid-fast bacilli on sputum smear; 1 had a healed fibrotic lesion in the lung suggestive of pulmonary TB; and another 2 patients had biopsy-proven tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis.

As for comorbid conditions, 4 patients were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, for which they were receiving oral hypoglycemic agents, and 18 (78%) had received but not responded to prior ulcer therapy with histamine-2 (H2) receptor antagonists. None of the patients studied were infected with HIV.

Investigations

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

All patients underwent endoscopy except 2. Of those who presented with gastric-outlet obstruction, 12 had duodenal stricture and 2 had pyloric stenosis. Additional findings noted in this group were chronic gastroduodenitis (2 cases), prepyloric ulcer (2), gastric ulcer (1) and duodenal ulcer (1).

Of the 6 patients with upper-GI hemorrhage, 2 had fundal varices, and another 2 had duodenal ulcers. Two patients who presented with hypotension after a massive hemorrhage were taken directly for surgery without endoscopy.

Two patients with obstructive jaundice had periampullary ulcers. In the patient with a gastric mass, a large polypoidal lesion was present along the greater curvature.

All patients had multiple biopsies during endoscopy, but in only 2 cases did preoperative endoscopic biopsies reveal TB (1 patient with gastric TB and another with a bleeding duodenal ulcer). In the patient suspected to have gastric malignancy, multiple endoscopic biopsies failed to reveal any malignancy.

Barium studies

Upper-GI radiography with barium contrast was carried out in 11 patients. Findings included deformed pylorus (in 2), duodenal stricture involving the first (7) or third part (1), and the mass lesion in the stomach, suggestive of malignancy, that has already been mentioned (1 patient).

Ultrasound and computed tomography

Three patients, 1 with a mass in the stomach and 2 with periampullary lesions, underwent ultrasound scans followed by CT imaging to evaluate the extent of disease. Findings included dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary ducts and bulky pancreas/ retropancreatic mass with peripancreatic lymph nodes. Duodenal dilatation caused by periduodenal lymph nodes was also observed.

Management

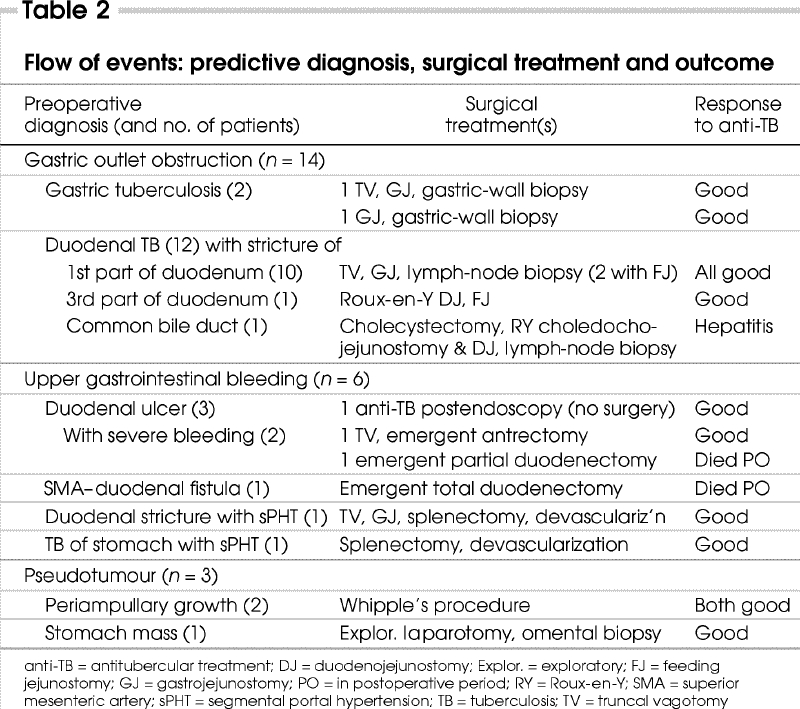

Of the 23 patients, 1 with a duodenal ulcer bleed was managed, when the biopsy of the ulcer showed features of TB, with antitubercular drugs alone. The remaining 22 required surgery either for diagnosis or for treating complications. Fourteen patients (66%) had associated enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, and 1 with gastric-outlet obstruction also had multiple ileal strictures. Preoperative diagnoses, the surgical procedures performed and outcomes are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

Surgical treatment

Gastric-outlet obstruction (n = 14)

The 12 patients who presented with obstruction (10 with pyloroduodenal stenosis and 2 with gastric TB) underwent truncal vagotomy and gastrojejunostomy, with or without feeding jejunostomy. Enlarged perigastric lymph nodes were biopsied.

Two additional patients underwent a Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy: 1 with a stricture of the third part of the duodenum, and another with an obstruction of the common bile duct, who required a bilioenteric bypass in addition.

Gastrointestinal bleeding (n = 5)

Of 2 patients who arrived at the centre bleeding from duodenal ulcers (and who were not correctly diagnosed from the endoscopic biopsy), 1 underwent truncal vagotomy and antrectomy. The other had multiple ulcers and required excision of the first and second parts of the duodenum. Persistent bleeding from the dissected area necessitated packing; despite these measures, the patient succumbed in the early postoperative period.

One patient presented with massive hemorrhaging from a superior mesenteric artery–duodenal fistula. She underwent a total duodenectomy with distal gastrectomy and closure of a rent in the superior mesenteric artery. She nevertheless died from persistent postoperative bleeding the day after her surgery.

Two patients with segmental portal hypertension caused by enlarged splenic hilar lymph nodes underwent splenectomy and devascularization of the stomach.

Pseudotumour (n = 3)

As shown in Table 2, 2 patients with suspected periampullary growths underwent Whipple's resection. Another had a large infiltrative lesion involving the entire stomach with multiple nodules in the omentum. Biopsy of an omental nodule revealed TB; the patient's condition improved with antitubercular drugs.

Postoperative period and follow-up

After their surgical treatments, all patients were given a standard 4-drug regime of antitubercular treatment (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol) for 4 months followed by an additional 8 months on 2 drugs (isoniazid and rifampicin).

Two patients who had undergone a gastrojejunostomy for gastric outlet obstruction continued to produce immoderate nasogastric aspirates despite a stoma judged adequate via endoscopy. When stomal adequacy was confirmed in each patient by re-exploration, only feeding jejunostomy was done. One patient recovered, but the other's original gastrojejunostomy did not become functional; that patient had to undergo yet another re-exploration, with an additional gastrojejunostomy on the anterior wall of the stomach. After this, that patient at last had an uneventful recovery.

One of the remaining patients had distal small-bowel obstruction at 5 months postoperatively, which responded to conservative management.

All patients tolerated the antitubercular regimen well except for 1 who developed drug-induced hepatitis 20 days after starting treatment. In this patient, the anti-TB treatment regimen was modified to ethambutol, ciprofloxacin and streptomycin, which were tolerated well.

Discussion

The most common site for GI involvement of TB is the ileocecal region, followed by the ascending colon, jejunum, appendix, duodenum, stomach, sigmoid colon and rectum.1 Involvement of the stomach and duodenum is rare; an autopsy series has reported an incidence around 0.5%.2,3

Possible causes for GD sparing include high acidity, a paucity of lymphoid tissue and rapid transit of food in the stomach.2,4,5,6 Long-term therapy with H2 blockers increases the incidence of GD TB;7 18 of our 23 patients had previously had therapy with H2 blockers. Gastric involvement most likely originates from adjacent celiac lymph nodes.7,8 In western countries, it is found either in immigrants from countries where TB is endemic or in patients with leukemia or AIDS who are immunosuppressed.9

Clinical features and sequelae

Because the clinical features are often vague and nonspecific, the disease is seldom suspected in the absence of pulmonary TB. In a collective review of 49 patients with duodenal TB,10 the most common presenting symptoms were pain (73%) and vomiting (55%), whereas GI bleeding was rare (16%). In our series, however, epigastric pain and vomiting occurred with similar frequency (60%), and bleeding occurred in 26% of cases.

Sequelae of GD TB that require surgery include obstruction of the gastric outlet, upper-GI hemorrhage, fistulous communication and perforation. Obstruction, the most common cause of presentation, occurs in the hypertrophic form or involves perigastric or periduodenal lymph nodes with subsequent fibrosis.11 Although hemorrhage is less common and is usually mild and intermittent, in our series nearly a quarter of patients arrived with bleeding. Half of these bled heavily, which caused 2 deaths.

Fistulous communication can occur between the duodenum and bile duct or renal pelvis.12,13,14 Massive hemorrhage from aortoduodenal fistula has been reported,15 but we found no report of a superior mesenteric artery – duodenal fistula as seen in 1 of our patients. Perforation peritonitis is also rare16 because of the surrounding inflammatory fibrosis induced by the ulcer.

Our series serves to highlight the rarity of gastric/ pancreatic pseudotumour as a manifestation of GD TB. We encountered only 3 such patients, in whom all preoperative attempts to obtain a histopathological diagnosis had failed.

Another interesting aspect of this study is the occurrence of segmental portal hypertension with bleeding fundal varices caused by obstruction of the splenic vein by perihilar lymph nodes. Again, this has not been reported before.

A chest x-ray may show evidence of pulmonary TB in up to 20% of cases.3 In our series, 14% did so. Barium meal study is nonspecific and may show segmental narrowing of the pylorus or duodenum, sometimes associated with ulcers or sinus tracts. Thickening of the gastric or duodenal wall, associated with enlarged local lymph nodes, is often visible via CT and may be the only clue to diagnosis.

Retroduodenal and pancreatic TB can sometimes mimic pancreatic tumours.17,18 Extensive mesenteric lymph- node disease is reported in 32%– 65% of cases of intestinal TB, but obstruction by enlarged pyloroduodenal nodes occurs in only 4%.6 In our series, 63% of cases involved mesenteric lymph nodes, with an unusually high incidence of periduodenal / perigastric lymph nodes (43%) causing gastric-outlet obstruction. Two patients in our series had CT features suggestive of periampullary mass or pancreatic tumour.

Upper-GI endoscopy may reveal duodenal bulb deformity.19 In gastric TB, it may present as multiple shallow ulcers, especially on the lesser curvature of the stomach20 or as a nondescript hypertrophic submucosal mass.21 Even in ulcerated lesions, endoscopic biopsy rarely reveals granulomas because of the predominantly submucosal location of these lesions and the failure of routine endoscopic biopsies to include the submucosa. In a review of 27 patients who underwent endoscopic biopsies of duodenal TB,13 although 20 had images of nonspecific duodenitis, granulomas were found in only 7. In our series, only 2 of 20 patients had positive endoscopic biopsies.

Acid-fast bacilli are rarely recovered from the biopsy material, although fine-needle aspiration cytology may have a higher yield.20 In a minority of cases it is possible to isolate mycobacteria in culture from gastric lavage.13 Polymerase chain reaction amplification of mycobacterial DNA may improve the rate of detection.22 However, false negatives are reported in 40%– 65% of cases.23

Management

When diagnoses of TB are established before surgery, most lesions regress with appropriate antitubercular treatment and do not require excision.24,25 Even in patients with strictures, endoscopic balloon dilatation has been successful.26 Elective surgery should be reserved for complications such as obstruction, fistula formation or intractable ulceration.

Obstruction

In patients with gastric-outlet obstruction, gastrojejunostomy is preferred over pyloroplasty, as intense fibrosis around the pyloroduodenal junction precludes safe pyloroplasty.27 Furthermore, subsequent stenosis associated with the healing of tubercular lesions may constrict the passage after pyloroplasty, resulting in a recurrence of symptoms.28

Obstruction persisting despite an adequate gastrojejunostomy stoma affected many of our patients, 2 of whom required resurgery. This may be related to prolonged gastric stasis and atony, or to involvement of the neural plexus. To overcome this problem we always do a feeding jejunostomy along with the gastrojejunostomy.

Bleeding

Persistent bleeding from a tubercular ulcer was managed with a vagotomy and antrectomy. When a patient presents with persistent abdominal symptoms of an unclear nature associated with constitutional symptoms such as low-grade fever or weight loss and a history of extraintestinal TB, a tubercular etiology should be considered.13

During surgery, suspicious lymph nodes and the stomach or duodenal wall should always be biopsied. Massive upper-GI hemorrhage, though encountered infrequently, carries a high mortality rate, especially when associated with multiple bleeding ulcers or arterioduodenal fistulae.

Pseudotumour

Findings from radiology, endoscopy and laparotomy occasionally mimic the features of a localized or disseminated malignancy. Whenever possible, resection should be attempted with curative intent, followed by appropriate antitubercular treatment. In our experience these patients tolerate resection well.

Conclusion

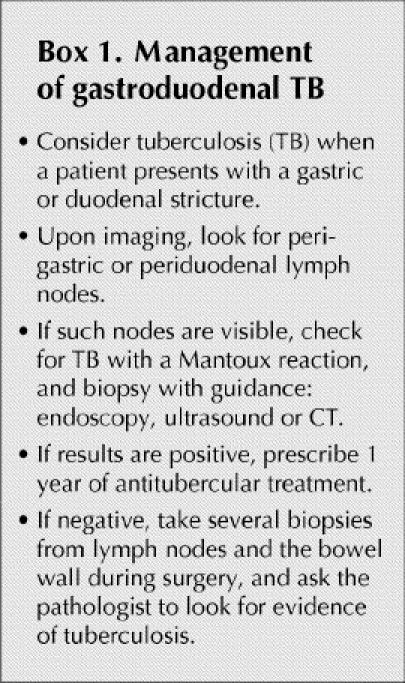

The algorithm we suggest for the management of patients with gastroduodenal TB is shown in Box 1.

Box 1.

As a final caution: the only means of treating and achieving a correct diagnosis in the rare patient with gastroduodenal/pancreatic pseudotumours from TB is operative resection — and one should not err on the side of doing too little. A diagnosis of tuberculosis in such cases, even in endemic countries, will be a “pleasant” histological surprise.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Girish K. Pande, Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, Sultan Qaboos University, PO Box 35, Al Khod, Muscat 123, Sultanate of Oman; fax 968-513419

Accepted for publication Nov. 10, 2003

References

- 1.Gorbach S. Tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract. In: Sleisenger M, Fordtran J, editors. Gastrointestinal diseases. Vol. 2. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1989. p. 363-72.

- 2.Palmer ED. Tuberculosis of the stomach and the stomach in tuberculosis: a review with particular reference to gross pathology and gastroscopic diagnosis. Am Rev Tuberc 1950;61:116-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Mukherji B, Singhal AK. Intestinal tuberculosis. Proc Assoc Surg East Afr 1968;2:71-5.

- 4.Marshall JB. Tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract and peritoneum: clinical reviews. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:989-99. [PubMed]

- 5.Tromba JL, Inglese R, Rieders B, Todaro R. Primary gastric tuberculosis presenting as pyloric outlet obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol 1991;86:1820-2. [PubMed]

- 6.Bhansali SK. Abdominal tuberculosis: experience of 300 cases. Am J Gastroenterol 1977;67:324-37. [PubMed]

- 7.Placido RD, Pietroletti R, Leardi S, Simi M. Primary gastroduodenal tuberculosis infection presenting as pyloric outlet obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:807-8. [PubMed]

- 8.Misra RC, Agarwal SK, Prakash P, Saha MM, Gupta PS. Gastric tuberculosis. Endoscopy 1982;14:235-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Snider DE Jr, Ropes WL. The new tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 1992;326:703-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gleason T, Prinz RA, Kirsch EP, Jablokow V, Greenlee HB. Tuberculosis of the duodenum. Am J Gastroenterol 1979;72: 36-40. [PubMed]

- 11.Fernandez OU, Canizares LL. Tuberculous mesenteric lymphadenitis presenting as pyloric stenosis. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40: 1909-12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Misra D, Rai RR, Nundy S, Tandon RK. Duodenal tuberculosis presenting as bleeding peptic ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol 1988; 83: 203-4. [PubMed]

- 13.Chaudhary A, Bhan A, Malik N, Dilawari JB, Khanna SK. Choledocho-duodenal fistula due to tuberculosis. Indian J Gastroenterol 1989;8:293-4. [PubMed]

- 14.Rodney K, Maxted WC, Pahira JJ. Pyeloduodenal fistula. Urology 1963;22:536-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Kodaira Y, Shibuya T, Matsumoto K, Uchiyama K, Tenjin T, Yamada N, Tanaka S. Primary aortoduodenal fistula caused by duodenal tuberculosis without an abdominal aortic aneurysm: report of a case. Surg Today 1997;27:745-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Berney T, Badaoui E, Totsch M, Mentha G, Morel P. Duodenal tuberculosis presenting as acute ulcer perforation. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:1989-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Bankier AA, Fleischmann D, Wiesmayr MN, Putz D, Kontrus M, Hubsch P, et al. Update: abdominal tuberculosis — unusual findings on CT. Clin Radiol 1995;50:223-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Naouri A, Tissot E. [Pancreatic pseudotumor caused by isolated tuberculous retro-duodenopancreatic adenopathy, a propos of a case]. Ann Chir 1990;44:480-3. [PubMed]

- 19.Tandon RK, Pastakia B. Duodenal tuberculosis as seen by duodenoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 1976;66:483-6. [PubMed]

- 20.Quantrill SJ, Archer GJ, Hale RJ. Gastric tuberculosis presenting with massive hematemesis in association with acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:1259-60. [PubMed]

- 21.Rohwedder J. Abdominal tuberculosis: a disease poised for reappearance. N Y State J Med 1989;89:252-4. [PubMed]

- 22.Brisson-Noel A, Aznar C, Chureau C, Nguyen S, Pierre C, Bartoli M, et al. Diagnosis of tuberculosis by DNA amplification in clinical practice evaluation. Lancet 1991;338:364-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Alvarez S, Mc Cabe WR. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis revisited: a review of experience at Boston city and other hospitals. Medicine 1984;63:25-55. [PubMed]

- 24.Gilinsky NH, Marks IN, Kottler NE, Price SK. Abdominal tuberculosis: a 10-year review. S Afr Med J 1983;64(22):849-57. [PubMed]

- 25.Anand BS, Nanda R, Sachdev GK. Response of tuberculous stricture to antituberculous treatment. Gut 1988;29:62-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Vij JC, Ramesh GN, Choudhary V, Malhotra V. Endoscopic balloon dilation of tuberculous duodenal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc 1992;38:510-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Thompson JN, Keshavarzian A, Rees HC. Duodenal tuberculosis. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1984;29:292-5. [PubMed]

- 28.Ali W, Sikora SS, Banerjee D, Kapoor VK, Saraswat VA, Saxena R, et al. Gastroduodenal tuberculosis. Aust N Z J Surg 1993; 63:466-7. [DOI] [PubMed]