Abstract

Research on anxiety treatment with African American women reveals a need to develop interventions that address factors relevant to their lives. Such factors include feelings of isolation, multiple roles undertaken by Black women, and faith. A recurrent theme across treatment studies is the importance of having support from other Black women. Sister circles are support groups that build upon existing friendships, fictive kin networks, and the sense of community found among African Americans females. Sister circles appear to offer many of the components Black women desire in an anxiety intervention. In this article, we explore sister circles as an intervention for anxious African American women. Culturally-infused aspects from our sister circle work with middle-class African American women are presented. Further research is needed.

Keywords: sister circles, African Americans, women, anxiety intervention

Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental health problems in this country (Kessler et al., 2004; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). Within multiple African Americans communities, anxiety disorders are classified as “nerves” or “bad nerves” (Neal-Barnett, 2003).

Epidemiological data indicates that anxiety disorders are more persistent among African Americans (Breslau, Kendler, Su, Gaxiola-Aguilar, & Kessler, 2005; Breslau, Gaxiola-Aguilar, Su, Williams, & Kessler, 2006). Clinical studies suggest that African Americans with anxiety diagnoses appear to experience the disorders for longer periods of time and at higher perceived levels of distress than their White counterparts (Friedman, Braunstein, & Halpern, 2006; Neal-Barnett & Crowther, 2000; Williams & Chambless, 1994; Williams, Chambless, & Steketee, 1998). Yet, African American adults have a lower lifetime prevalence rate for anxiety disorders than their non-Hispanic White counterparts (Breslau et al., 2005). Despite these findings regarding persistence and distress, little research has been conducted on anxiety treatment with African Americans.

The scant literature available primarily focuses on African American women. Data from these studies underscore the need for interventions that address factors relevant to African American women that may contribute to the development of anxiety as well as impede intervention’s effectiveness (Carter, Sbrocco, Gore, Marin, & Lewis, 2003; Feske, 2008; Friedman, Braunstein, & Halpern, 2006; Johnson, Mills, DeLeon, Hartzema, & Haddad, 2009; Neal-Barnett et al, 2011; Williams et al., 1998). These factors include feelings of isolation (i.e., I am the only one with this problem), the multiple roles undertaken by Black women, and faith (Carter et al., 2003; Feske, 2008; Friedman et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2009; Neal-Barnett et al., 2011; Williams & Chambless, 1994). A common theme throughout these studies is the importance of having the support of other Black women.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to investigate the utility of employing an intervention predicated on the support of other Black women. An already existing model, the sister circle, is described. We then address methods of infusing cognitive behavioral therapy in culturally relevant ways. Specifically, we focus on a music-based approach to cognitive restructuring and on decision making regarding the use of relaxation and calming techniques. We also examine the integration of non-Western techniques (mindfulness, transcendental meditation) with CBT into the intervention. We conclude with an appeal for more research on the sister circles intervention. This paper extends our work on anxiety and anxiety-related disorders among African American women (Meinert, Blehar, Peindl, Neal-Barnett, & Wisner, 2003; Neal-Barnett, 2003; Neal-Barnett & Crowther, 2000; Neal-Barnett & Stadulis, 2006; Neal-Barnett, Statom, & Stadulis, 2010). It builds on an earlier focus group paper concerning whether and how sister circles could be used in the treatment of anxiety (Neal-Barnett et al., 2011), and it lays the groundwork for an empirical investigation of the effectiveness of sister circles, to be reported in the future.

Sister Circles

Sister circles are support groups that build upon existing friendships, fictive kin networks, and the sense of community found among African Americans females. Originally embedded in the Black club movement (Giddings 1984), sister circles have been a vital part of Black female life for the last 150 years. Sister circles exist directly in the community and within organizations that are components of women’s lives. Many women have ties to these organizations that go back generations. Members often refer to one another as Sister X or Sister Y, building on a sense of collectivism and existing kinship networks (Black Women’s Health Imperative, 2000; Boyd, 1993). Inherently, sister circles provide Black women with help, support, knowledge, and encouragement (Boyd, 1993; Giddings, 1984).

Over the course of time, the term sister circle has come to mean different things to different people. For some, a sister circle is a group of women within an organization (i.e., church, service club, workplace) who are brought together by a common theme, such as healthy eating, greater spirituality, love of books, etc. For others, a sister circle is a group of women experiencing the same health concern who come together for education and support. For example, the term sister circle has been used to designate breast cancer, diabetes, and stroke support groups. Under this definition, the sister circle may be led by a professional (nurse, health educator, therapist) or by a survivor, that is, someone who has lived or is living with the health concern. In many cases, groups will use either a culturally infused or African-centered standard curriculum. In other words, developers either incorporate elements that are unique to the participants’ lives as Black women (“culturally infused”), or they link the curriculum to concepts that reinstill traditional African and African American cultural values in people of African descent (“African-centered”)(Gilbert, Harvey & Belgrave, 2009). Gaston and Porter’s Prime Time® sister circles (Gaston, Porter, & Thomas, 2007), designed to promote physical well-being in middle-aged African American women, are examples of expert-led culturally infused sister circles. Healer Women Fighting Disease (Gilbert & Goddard, 2007) is an HIV and substance abuse prevention for African Americans led by a trained facilitator. Although “sister circle” is not in its title, the Healer Women Fighting Disease approach contains many of the components of an African-centered sister circle (Gilbert & Goddard, 2007).

The term sister circle has also been used to designate group therapy for African American women (Boyd, 1993). Led by a mental health professional, women in the group are connected by similar diagnoses or mental health concerns. This therapeutic use of sister circles was popularized by psychotherapist Julia Boyd in her best-selling book In the Company of My Sisters (1993). In the book, members of Boyd’s sister circle address the issue of Black women and self-esteem and how it affects relationships, work, and other aspects of their lives including physical and mental health. Members reflect on images of Black women, multiple roles of Black women, family legacies, and the importance of African Americans’ shared history (Boyd, 1993).

The sister circle concept has also been modified for use with African American adolescent girls. Designed in a developmentally appropriate way, these sister circles are often sponsored by African American sororities, churches, educational institutions, and community agencies. Adult female health or mental health professionals lead sister circles for adolescents, sometimes assisted by participants’ peer mentors. Frequent themes of these sister circles are self-esteem, sexuality, and transition. The faith–based E.V.E. (Esteem, Values, and Education), in which education professionals with help from female congregation members nurture and guide adolescent girls, is an example of an adolescent sister circle (Arlington Church of God, 2010).

Given the numerous uses and definitions of sister circles, we believe it is important to operationally define sister circles as they relate to our work with anxious African American women. We define a sister circle as a subset of women embedded within an existing Black women’s organization who share an existing concern related to anxiety and fear. As part of our research, we hypothesize that women within the sister circle have a preexisting relationship and a commitment individually and collectively to the subset. We further hypothesize that facilitation by women who are both part of the existing organization and part of the subset is a critical component to our sister circles. By definition, our conceptualization of a sister circle differs from group therapy, as therapists do not facilitate our sister circles. Sister circles are a peer-supported intervention; however, we hypothesize that specific characteristics—individual commitment to the organization and subset—are necessary for it to be effective.

Despite the widespread use of African American sister circles, limited empirical research is available on their feasibility and effectiveness (Gaston et al., 2007; Gilbert, Harvey, & Belgrave, 2009). The available research and anecdotal data indicate that sister circles can be effective for healthy eating and exercise, HIV and substance abuse prevention, and raising self esteem (Black Women’s Health Imperative, 2010; Boyd, 1993; Gaston et al., 2007; Gilbert et al., 2009). Sister circles appear to be a natural conduit for delivering a psycho-educational anxiety intervention. Within the subset, relationships and trust seem to already be established (Neal-Barnett et al., 2011).

Sister Circles for Anxious African American Women

We believe, given our definition, that sister circles may be able to serve as an early intervention or prevention for anxious African American women. Therefore, we are piloting sister circles for middle-class African American women. To the best of our knowledge, these are the first sister circles aimed at anxiety. Using best practices procedures, our team developed a manualized psycho-educational anxiety intervention based on the book Soothe your nerves: The Black women’s guide to understanding and overcoming anxiety, panic, and fear (Neal-Barnett, 2003). We designed the intervention to target Black women who want to manage their anxiety and fear. A significant number experienced at least one panic attack within the past year. Building upon the social support inherent in both sister circles and Black women’s organizations (Gaston et al., 2007; Giddings, 1984; Neal-Barnett, 2003), we embedded sister circles within African American women’s service organizations. We chose the facilitators who would deliver the intervention from the organizations’ memberships. In preparing the facilitators to lead the circles, we used the train-the-trainer model. Facilitators participated in a weekend sister circle retreat and follow-up sessions. Over a two-month period, four sets of facilitators each led five-week sister circles. Sister circles varied in length from 60–90 minutes and ranged in size from six to nine participants. Data collection is now complete and results should be available within the next six to twelve months. In this final section, we share several examples of how we culturally infused the curriculum to address the needs of African American professional women.

Cognitive restructuring and deconstructing erroneous thoughts

The most effective treatment of adult anxiety disorders is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). As it relates to anxiety, CBT consists of three major components: understanding the relationship between thoughts, emotions, and behaviors; alleviating physical symptoms of anxiety; and eliminating avoidance or agoraphobic behavior (Barlow, 2002). Common techniques of CBT for anxiety disorders are exposure, cognitive restructuring, response prevention, and self-monitoring. Despite the overwhelming evidence of CBT efficacy, scant research has been conducted using CBT with anxious African American women. When CBT has been used with this population, the findings support the inclusion of gender-race specific modifications and infusion (Carter et al., 2003; Feske, 2008; Friedman et al., 2006; Williams & Chambless, 1994).

In our clinical work with African American women, we have found cognitive restructuring to be a difficult skill to teach. Often our clients complain that it is “too hard” and that they “can’t do it.” Using the support inherent in sister circles, building on the role of music in the African American community (Jones & Jones, 2000; Lane, 1994) and on existing music intervention and anxiety literature (Choi, Lee, & Lim, 2008; Gold, Soli, Kruger, & Lie, 2009), we developed two exercises to introduce cognitive restructuring: a) the So What Chorus and b) Build Your Own Theme Song© (BYOTS). Whereas African-centered interventions often use music to set the tone or to convey a sense of collectivism (Goggins, 1997; Goggins personal communication, September 1, 2010; Lewis, 1988), our review of the literature does not reveal that music had previously been used as a form of cognitive restructuring

Music is a powerful tool for overcoming emotion. For generations, songs filled with messages of hope, encouragement, spirituality, and empowerment have permeated the hearts and minds of African Americans, often giving them the strength to persevere in the face of great odds (Jones & Jones, 2000; Lane, 1994). Recent research has found that music intervention can significantly decrease anxiety symptoms in psychiatric hospitalized populations (Choi, Lee, & Lim, 2008). A review and meta-analysis of the literature found that as a complementary treatment, music interventions can assist in the reduction of anxiety symptoms as measured by global state rating scales (Gold, Solli, Kruger, & Lie, 2009).

The So What Chorus (Neal-Barnett, 2003) is predicated on the African American musical tradition of call and response (Bell, 1997). Frequently seen in gospel and rap music, call and response is a succession of two distinct phrases in which the second phrase is a direct response to the first phrase. In the So What Chorus, facilitators introduce sister circle participants to the concept of erroneous or “What if” thinking. Participants are taught to identify a “What if” thought and respond to it by answering “So What?” For example:

Sister Call: “What if” I go to work and have a panic attack?”

Circle Response: SO WHAT?

Sister Call: Everyone will know something is wrong with me.

Circle Response: SO WHAT?

Sister Call: Everyone will think I’m crazy.

Circle Response: SO WHAT?

Sister Call: No one wants to work with a crazy person.

Circle Response: SO WHAT?

Sister Call: I won’t have a job and my reputation will be ruined.

Circle Response: SO WHAT?

Sister Call: SO WHAT! The only way I can lose my job over a panic attack is if I choose to do nothing about it. Because of my Sister Circle, I have the tools to manage and overcome panic. (Neal-Barnett, 2003).

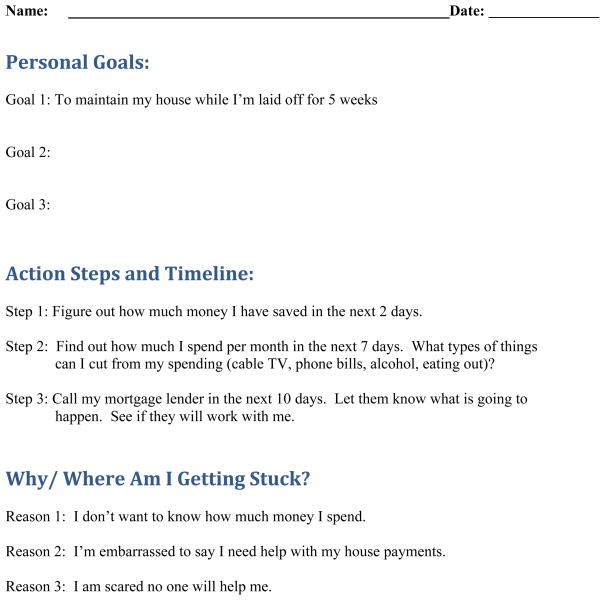

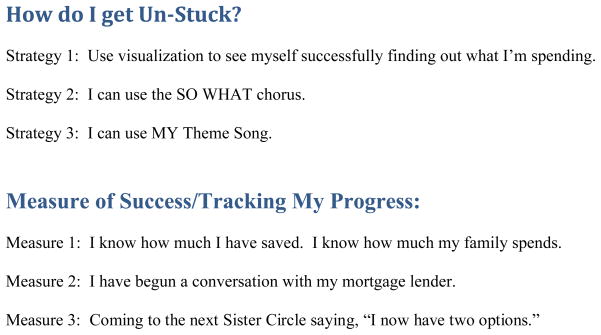

As the sister circle practices the So What Chorus, some women may in actuality state a reality or a “What is.” This occurrence provides the opportunity to teach problem solving via an action plan. As seen in Figure 1, the key to the action plan is not only identifying the problem and delineating concrete steps, but also raising awareness of the factors that are preventing one from taking action. Once participants acknowledge the barriers to taking action, the Sister Circle once again applies the So What Chorus to deconstruct the erroneous thought.

Figure 1.

Action Plan for Overcoming Anxiety and Panic Attacks

Recognizing and deconstructing erroneous thoughts is one part of cognitive restructuring. The second part involves replacing the negative, erroneous thoughts with positive thoughts. In the Build Your Own Theme Song© exercise, participants construct their own theme song drawing on information from previous sessions and based on an existing song with which they are familiar. Via an interactive approach, participants learn how to use “their” song to push out negative, anxiety-laden thoughts and replace them with positive, non-anxiety thoughts. For example:

Blessed Assurance Original Version1

This is my story, this is my song, Praising my savior all the day long. This is my story, this is my song,

And I’m praising my savior all the day long (Crosby & Knapp, 1873)

BYOTS Version

I can encourage myself to sing I can empower myself to believe I can help myself learn to proceed

True to my vision and my destiny (Anonymous, 2010)

Although our sister circles are not faith-based in nature, when given the opportunity to chose original songs for use in the creation of their own theme songs, most participants chose an original song that contained a spiritual component. The overwhelming choice of hymns or gospel songs suggests that for this group of middle-aged, middle-income African American women, spirituality may be an important subcomponent of managing anxiety. Keyes and Reitzes (2007), in their investigation of religious identity among older working and retired adults, found that self-esteem increased and depressive symptoms decreased as religious identity increased. Research specific to African Americans and mental health suggests that religion serves as a generally protective factor against psychological morbidity (Levin, Chatters, & Taylor, 2005). Although we did not collect data on participants’ religious identity, the theme song choices suggest that most sister circle members, to some degree, may view religion as an important aspect of their lives.

Via the theme song, participants appeared to learn that “when thoughts enter in that make me afraid my song will drive them away” (Neal-Barnett & Salley, 2007). In other words, sister circle members learned the basic tenets of cognitive restructuring. Data detailing the effectiveness of these exercises should be available in six to twelve months.

Relaxation, Mindfulness, and Transcendental Meditation

Relaxation is a traditional element of CBT. A more recent advancement in CBT is its integration with non-Western techniques such as mindfulness and transcendental meditation. Research has shown all three strategies to be effective components of anxiety and stress interventions (Kabat-Zinn, 2003; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006; Vallejo & Amaro, 2009). Some African American women, however, may misinterpret the predominantly Buddhist roots of mindfulness as eschewing God or Allah. The unmodified use of these techniques could thus inadvertently reinforce cultural mistrust (Whaley, 2001a; Whaley, 2001b). Therefore, in introducing non-Western techniques to African American women, it appears important to convey in both words and actions that a change in beliefs or philosophies is neither expected nor warranted. Whereas support exists for using non-Western techniques such as transcendental meditation and mindfulness with low-income inner city populations (Schneider et al., 1995; Vallejo & Amaro, 2009), it is clear from the literature that great care must be taken to use the iterative process inherent in community-based participatory research to adapt the techniques for African American populations (Schnieder et al., 1995; Vallejo & Amaro, 2009). Our own work is with professional African American women. Within our focus groups, women expressed a strong preference for relaxation (Neal-Barnett et al, 2011). Therefore, in our Sister Circles, we teach the well-known CBT technique progressive muscle relaxation (PMR: Jacobson, 1938). This decision is in line with the community-based participatory research approach we used for developing a culturally infused CBT intervention.

Conclusion

The specific sister circles described here are subsets of women embedded within existing Black women’s organizations who are brought together by an expressed concern related to anxiety and fear. Non-therapists lead sister circles. For this reason, exposure and response prevention is not formally part of the curriculum. Informally however, these two important components of anxiety intervention occur throughout the sister circle via weekly participation in the sister circle and assignments attached to the So What Chorus and BYOTS.

Many African American women avoid seeking help for anxiety because they are afraid others will see them as weak (Johnson et al., 2009; Neal-Barnett et al., 2011). For these women, attending and sharing within them sister circle directly exposes them to a core fear. A form of ERP appears to occur with the assignment to practice the So What Chorus and BYOTS in real-life anxiety provoking situations.

Existing research documents difficulties associated with implementing ERP with African American samples (Carter et al., 2003; Feske, 2008; Williams & Chambless, 1994). Thus, the question arises whether informal ERP limits or enhances the sister circle intervention. Forthcoming data from participants may shed light on the answer.

Sister circles offer a way to apply a culturally relevant version of CBT (Gaston et al., 2007; Neal-Barnett et al., 2011). Equally important, they offer a way to provide intervention in a manner that is endorsed by anxious African American women (Johnson et al., 2009; Neal-Barnett et al., 2011).

Our operational definition of sister circles embeds them within an organization. Relationships are already in place. Given this unique aspect of our sister circles, the question becomes whether what occurs in the anxiety sister circle can be replicated in traditional intervention or group therapy. We believe this question can be best answered by well-designed intervention research.

As our earlier research demonstrates, it is not that Black women do not want assistance for anxiety difficulties: rather, they want assistance that takes into account their experiences as Black women (Neal-Barnett et al., 2011). The So What Chorus and BYOTS build upon some of these experiences and present cognitive restructuring in a culturally relevant way. Employing a community-based participatory approach allowed us to make an informed choice to use progressive muscle relaxation and not mindfulness. Preliminary results suggest that the sister circles may make a positive impact on the lives of these professional African American women. Additional research is needed on this valuable mechanism for anxiety intervention.

Acknowledgments

Grant No. 5R21MH076722-02 awarded by the National Institute of Mental Health to Angela Neal-Barnett, Ph.D. supported this research.

Special thanks to Lori Crosby, Psy.D. and Monica Mitchell, Ph.D. Co-Directors Innovations

Footnotes

Song selection reflects the participants’ choice. With a different sample of African American women, song selection may be secular versus spiritual. In no way is song selection reflective of the type intervention taught or presented.

Contributor Information

Angela Neal-Barnett, Kent State University.

Robert Stadulis, Kent State University.

Marsheena Murray, Kent State University.

Margaret Ralston Payne, Kent State University.

Anisha Thomas, Kent State University.

Bernadette B. Salley, Optimistic Note, LLC

References

- Anonymous. My theme song. Kent State University; Kent, OH: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arlington Church of God. About our senior pastor. 2010 Retrieve September 26, 2010 from www.arlingtonchurch.org.

- Black Women’s Health Imperative. Our story. 2010 Retrieved February 10, 2010 from 1996) http://www.blackwomenshealth.org/site/c.eeJIIWOCIrH/b.3561065/k.89/Our_Story.htm.

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bell D. Gospel choirs: Psalms of survival in an alien land call home. New York: Basic Books; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J. In the company of my sisters. New York: Dutton; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Gaxiola-Aguilar S, Su M, Williams D, Kessler R. Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in USA National sample. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(1):57–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Kendler KS, Su M, Gaxiola-Aguilar S, Kessler R. Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(3):317–327. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704003514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter MM, Sbrocco T, Gore KL, Marin NW, Lewis EL. Cognitive behavior therapy versus a wait list control in the treatment of African American women with panic disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27(5):505–518. doi: 10.1023/A:1026350903639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi AN, Lee MS, Lim HJ. Effects of group music intervention on depression, anxiety, and relationships in a psychiatric population: A pilot study. Journal of Alternative Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(5):567–570. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby FJ, Knapp PP. Blessed assurance. 1873 Retrieved May 25, 2010 http://www.hymnsite.com/hymndex.htm.

- Feske U. Treating low-income and minority women with posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study comparing prolonged exposure and treatment as usual conducted by community therapists. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(8):1027–1040. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Braunstein JW, Halpern B. Cognitive behavioral treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia in a multiethnic urban outpatient clinic: Initial presentation and treatment outcome. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2006;13(4):282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2006.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston MH, Porter GK, Thomas VG. Prime Time Sister Circles: Evaluating a gender-specific, culturally relevant health intervention to decrease major risk factors in mid-life African-American women. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99(4):428–438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddings P. When and where I enter: The impact of Black women on race and sex in America. New York: HarperCollins; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DJ, Goddard L. HIV prevention targeting African American women: Theory, objectives, and outcomes from an African-centered behavior change perspective. Family & Community Health: The Journal of Health Promotion & Maintenance. 2007;30(1):S109–S111. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200701001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DJ, Harvey AR, Belgrave FZ. Advancing the Africentric paradigm shift discourse: Building toward evidence-based Africentric interventions in social work practice with African Americans. Social Work. 2009;54(3):243–252. doi: 10.1093/sw/54.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goggins L., II . African-Centered rites of passages and education. Chicago: African American Images; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gold C, Solli HP, Kruger V, Lie SA. Dose–response relationship in music therapy for people with serious mental disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(3):193–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson E. Progressive relaxation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Mills TL, DeLeon JM, Hartzema AG, Haddad J. Lives in isolation: Stories and struggles of low-income African American women with panic disorder. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2009;15(3):210–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones F, Jones AC. The triumph of the soul: Cultural and psychological aspects of African American music. Westport CT: Praeger; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10(2):144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, Jin R, Pennell BE, Walters EE, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H. The USA National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): Design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Reitzes DC. The role of religious identity in the mental health of older working and retired adults. Aging and Mental Health. 2007;11(4):434–443. doi: 10.1080/13607860601086371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane D. Music as medicine: Deforia Lane’s life of music, healing and faith. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Levin J, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Religion, health and medicine in African Americans: Implications for physicians. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(2):237–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. Herstory: Black female rights of passage. Chicago: African American Images; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Meinert JW, Blehar M, Peindl KS, Neal-Barnett AM, Wisner KL. Bridging the Gap: Steps toward recruitment of African American women in mental health studies. Academic Psychiatry. 2003;27(1):21–28. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.27.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal-Barnett AM. Soothe your nerves: The Black women’s guide to understanding and overcoming anxiety, panic, and fear. New York: Fireside/Simon and Schuster; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Neal-Barnett AM, Crowther JH. To be female, anxious, middle class, and Black. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2000;24(2):132–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb00193.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neal-Barnett AM, Salley BB. My song is the key. Stow, OH: Salley Music; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Neal-Barnett A, Stadulis R. Affective states and racial identity among African American women with trichotillomania. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98(5):753–757. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal-Barnett A, Stadulis R, Payne MR, Crosby L, Mitchell M, Williams L, Williams-Costa C. In the company of my sisters: Sister circles as an anxiety intervention for professional African American women. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;129:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal-Barnett, Statom D, Stadulis R. Trichotillomania symptoms in African Americans: Are they related to anxiety and culture? CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RH, Staggers F, Alexander CN, Sheppard W, Rainforth M, Kondwani K, Smith S, King CG. A randomized control study of stress reduction for hypertension in older African Americans. Hypertension. 1995;26:820–830. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.5.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health NIH Publication 06-3879. Rockville, MD; Author: 2006. Anxiety disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Z, Amaro H. Adaptation of mindfulness-based stress reduction program for addiction relapse prevention. The Humanistic Psychologist. 2009;37(2):192–206. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL. Cultural mistrust: An important psychological construct for diagnosis and treatment of African Americans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2001a;32(6):555–562. doi: 10.1177/0011000001294003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL. Cultural mistrust and mental health services for African Americans: A review and meta-analysis. The Counseling Psychologist. 2001b;29(4):513–531. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.32.6.555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EK, Chambless DL, Steketee G. Behavioral treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in African Americans: Clinical issues. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1998;23(2):163–170. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7916(98)00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EK, Chambless DL. The results of exposure-based treatment in agoraphobia. In: Friedman S, editor. Anxiety disorders in African Americans. New York: Springer; 1994. pp. 149–165. [Google Scholar]