Abstract

To begin to characterize the temporal profile of behavioral sensitization to the amphetamine derivative MDMA, rats were treated with either saline or MDMA (5.0 mg/kg) twice daily for 5 days, followed by a challenge injection of MDMA (2.5 mg/kg) either 15 or 100 days later. Because we found previously that contextual drug associations are important to the expression of behavioral sensitization to MDMA following relatively short withdrawal periods, rats received the repeated injections in either their home cages (unpaired group) or the activity monitors that were used for tests of sensitization on challenge day (paired group). Locomotor sensitization was evident at 15 days of withdrawal, but only in the paired MDMA-treated group. Interestingly, however, sensitization was apparent at 100 days of withdrawal in both paired and unpaired rats, but the form of sensitization differed between groups. Thus, sensitization in paired rats was expressed as an increase in stereotypy, whereas sensitization in unpaired rats was expressed as an increase in locomotion, paralleling locomotion levels in paired animals at 15 days of withdrawal. These results suggest that the neural changes that underlie behavioral sensitization to MDMA are quite enduring but involve an interaction between withdrawal time and the context of drug administration.

Keywords: CONTEXT, DRUG ABUSE, MDMA, SENSITIZATION, WITHDRAWAL, RAT

INTRODUCTION

Exposure to a wide range of drugs has been shown to produce an enduring change in behavior termed sensitization. Behavioral sensitization refers to the augmentation of the psychomotor effects of drugs following repeated intermittent exposure (Segal and Mandell, 1974; Paulson et al., 1991; Stewart and Badiani, 1993) and represents a striking form of behavioral plasticity induced by drugs of abuse. We and others have reported that the amphetamine derivative 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA; ecstasy) produces behavioral sensitization (Spanos and Yamamoto, 1989; Dafters, 1995; Kalivas et al., 1998; McCreary et al., 1999; Ramos et al., 2004; Ball et al., 2006, 2009, 2010) but whether it persists beyond 4 weeks of withdrawal is not known. Considering the increasing use of MDMA and the paucity of data regarding its long-term effects, it is important to investigate the time-course of behavioral sensitization to MDMA. Thus, the goal of the present study was to determine whether the expression of behavioral sensitization to MDMA is apparent following a very long withdrawal period (100 days) and also to compare this behavior, both quantitatively and qualitatively, to the sensitized response following a shorter withdrawal period (15 days). Because we found previously that contextual drug associations are important to the expression of behavioral sensitization to MDMA following relatively short withdrawal periods (Ball et al., 2006, 2010) we also manipulated the context of drug administration to determine its influence on the expression of long-term sensitization.

METHODS

Subjects

Adult male, Sprague-Dawley rats (N = 64) weighing 300–400 g at the commencement of treatment and supplied by Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN) were used for all experiments. Rats were housed individually in hanging wire cages under standard laboratory conditions (12-hr light cycle from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM) with free access to food and water, except during a period of approximately 30 days beginning approximately 18 days before the initial treatment period during which time rats were maintained between 85 and 90% of free-feeding body weight in order to collect preliminary data for a separate study. During a portion of this time (not including the treatment period) rats pressed a lever for food reinforcers on various ratio schedules of reinforcement. All procedures were conducted between 09:00 17.00 h, were in compliance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (Academies, 2003), and were approved by the Bloomsburg University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Apparatus

Open-field horizontal behavior was measured in standard rat open-field arenas (Model E63-20; Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, PA) that use a photo beam grid to track animals’ location. Arenas were housed in sound-attenuating, ventilated cubicles and connected to a PC with Tru Scan activity-monitoring software. The variables measured were ambulatory distance and stereotypy time. The ambulatory distance measure is the floor plane total movement distance less stereotypic movement distance, and is a measure of locomotion. Stereotypy reflects repetitive movements that do not contribute to large location changes progressively further from the starting point. Stereotypic movement is the total time of stereotypic movement, which is defined as the total number of coordinate changes less than plus or minus 0.999 beam spaces in each floor plane coordinate and back to the original point that do not exceed 2 s apart.

Drug treatment

Rats were randomly assigned to one of four treatment conditions (n = 16/condition) and received two daily i.p. injections (~6 hr apart) of either MDMA (5.0 mg/kg; weight of salt) or saline vehicle (1.0 ml/kg) for 5 consecutive days in either their home cages (unpaired group) or the activity monitors that were used later for tests of sensitization (paired group). Animals in the paired groups were left in the activity monitors for 30 min following injections. (±)-MDMA was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, Research Triangle Park, NC) and was dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline. The dose of MDMA and treatment schedule were chosen based on our previous studies (Ball et al., 2006; Ball et al., 2009; Ball et al., 2010).

Challenge injections

Within each treatment group rats were randomly assigned to receive a challenge injection of MDMA (2.5 mg/kg) either 15 or 100 days after the last injection of the treatment phase, for a total of eight conditions (n = 8/condition). On challenge day, all rats were placed in the activity monitors for a 20-min habituation period just prior to the challenge injection and a 60-min recording session. One rat in the MDMA/paired/100 day withdrawal group was sacrificed before the challenge day due to an infection at the injection site (thus, n = 7 in that condition).

Statistical analysis

Ambulatory distance (cm) and stereotypy time (s) on the challenge day were calculated in 20-min blocks. Data for each dependent variable were analyzed by means of a four-way, mixed ANOVA with time (in 20-min blocks) as the within-subjects factor and dose (saline and MDMA pretreatment), context (home cage and activity monitors for unpaired and paired groups, respectively), and withdrawal period (15 and 100 days) as between-subjects factors. ANOVAs were followed by Bonferroni post-tests.

RESULTS

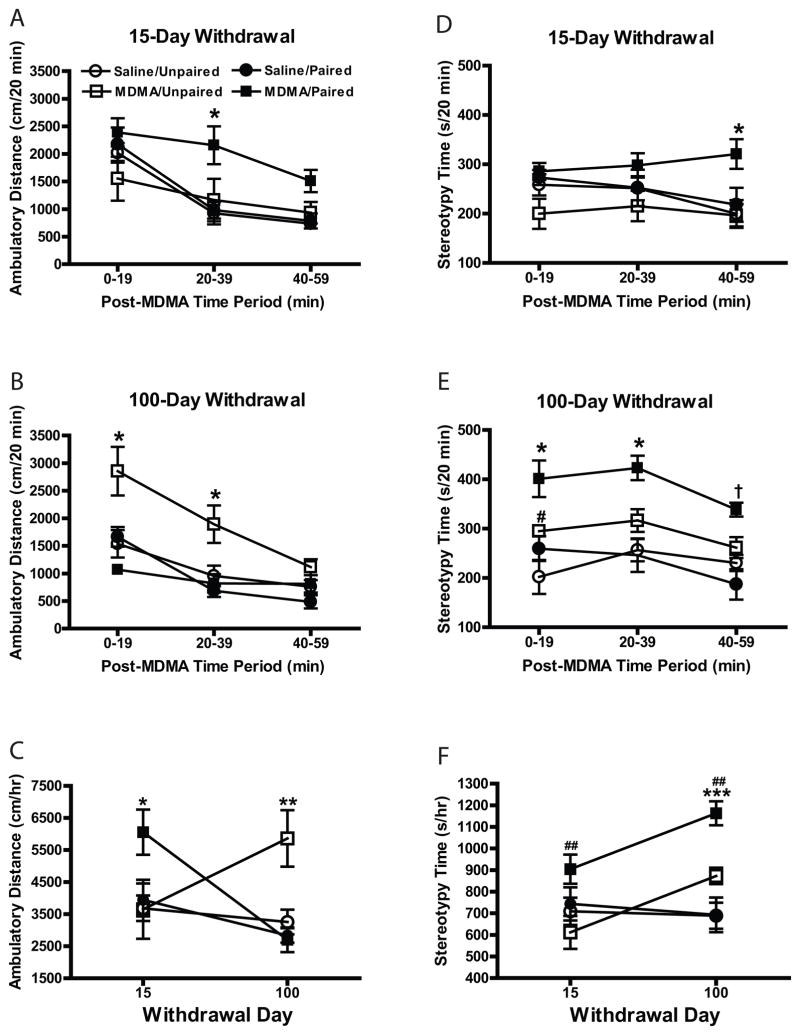

As seen in Fig. 1A, sensitization of MDMA-induced locomotor activity was evident at 15 days of withdrawal in the paired MDMA-treated group but not in the unpaired group. At 100 days of withdrawal, however, only those animals treated with MDMA in their home cage displayed locomotor sensitization (see Fig. 1B). Thus, although there was a significant main effect of dose [F(1, 55) = 7.02, p < .05], there also were significant context X withdrawal [F(1, 55) = 13.22, p < .01] and dose X context X withdrawal [F(1, 55) = 8.09, p < .01] interactions. As Fig. 1C shows, the overall magnitude of the sensitized locomotor response in unpaired MDMA-treated animals at 100 days of withdrawal paralleled that of paired animals at 15 days of withdrawal [mean (±SEM) distance (cm/hr) = 5,862.00 (878.93) and 6056.25 (704.25), respectively].

Fig. 1.

(A, B) Time-course of locomotor activity in 20-min blocks across 60-min session following MDMA challenge (2.5 mg/kg), in rats treated 15 or 100 days earlier with saline vehicle or MDMA injections (5.0 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days) in either their home cages (unpaired group) or the activity monitors that were used for subsequent tests of sensitization (paired group). *p < .05 compared with all other treatment groups. (C) Overall locomotor activity in response to MDMA challenge. *p < .05 and **p < .01 compared with all other treatment groups. (D, E) Time-course of stereotypy in 20-min blocks across 60-min session following MDMA challenge. *p < .05 compared with all other treatment groups; #p < .05 compared with saline/unpaired group; †p < .05 compared with both saline groups. (F) Overall stereotypy time in response to MDMA challenge. ##p < .01 compared with MDMA/unpaired; ***p < .001 compared with saline groups. All points represent mean (±SEM).

As shown in Fig. 1D, stereotypy scores were similar between treatment groups at 15 days of withdrawal; at 100 days of withdrawal, however, paired, but not unpaired, MDMA-treated animals displayed sensitization of stereotypy across the entire session [see Fig. 1E; F(1, 55) = 9.91, p < .01 and F(1, 55) = 8.41, p < .01 for dose X withdrawal and dose X context interactions, respectively]. As shown in Fig. 1F, overall stereotypy scores were significantly higher in paired MDMA-treated animals compared to unpaired MDMA-treated animals at 15 days of withdrawal, and sensitization of this behavioral measure is clearly evident in paired MDMA-treated animals at 100 days of withdrawal (68 and 33% more stereotypy time compared with saline and MDMA/unpaired groups, respectively at 100 days of withdrawal).

DISCUSSION

We found that locomotor sensitization in response to a challenge injection of MDMA was evident at 15 days of withdrawal from repeated administration, but only in rats that received the previous injections in the activity monitors that were used for subsequent tests of sensitization (paired animals). Interestingly, however, sensitization was apparent at 100 days of withdrawal in both paired and unpaired MDMA-treated rats, but the form of sensitization differed. These results suggest that the neural changes that underlie behavioral sensitization to MDMA are quite long lasting but involve an interaction between withdrawal time and the context of drug administration.

Acute administration of lower doses of amphetamine-like stimulants produces a behavioral response in which locomotion is prominent, whereas higher doses result in a multiphasic response that includes an intermediate phase of focused stereotypy during which locomotion declines or is absent (Segal, 1975; Rebec and Bashore, 1984). In addition, the stereotypy phase occurs sooner and lasts longer as the dose increases. Thus, the increase in stereotypy observed at 100 days in paired animals may indicate a stronger form of sensitization. If so, MDMA-induced sensitization not only is long-lasting, but also continues to increase in magnitude for at least 100 days following the cessation of drug exposure. Because we used an indirect measure of stereotypy, however, it will be important to investigate the time-course of sensitization to MDMA using additional techniques, including direct qualitative observations.

Although it is well documented that the magnitude of sensitization to amphetamine-like stimulants, including MDMA, increases with increasing withdrawal times (Hitzemann et al., 1977; Kolta et al., 1985; Ball et al., 2006), little data are available regarding qualitative changes in the sensitized behavioral response as a function of withdrawal time. Nonetheless, Leith and Kuczenski (1982) reported that the increase in post-stereotypy locomotion associated with behavioral sensitization to amphetamine lasted < 2 months, whereas the more rapid onset of focused stereotypy associated with sensitization was still present following a 3-month withdrawal period. Similarly, Paulson et al. (1991) reported an enhancement of post-stereotypy locomotion in animals challenged with amphetamine following 1 month of withdrawal from repeated injections, but not at earlier (≤ 2 weeks) or later (≥ 3 months) withdrawal time points. Our finding that sensitization of locomotor activity at 15 days of withdrawal in paired animals was replaced by stereotypy at 100 days of withdrawal provides the first evidence of qualitative changes in MDMA-induced sensitization as a function of withdrawal time and suggests that there is overlap in the long-term behavioral effects of amphetamine and MDMA. In addition, the finding that sensitization in upaired rats was apparent at 100 days of withdrawal but completely absent at 15 days of withdrawal shows that administration of MDMA in the home cage did not prevent, but rather delayed, the development and/or expression of sensitization.

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant DA027960 (K.T.B.). MDMA was generously provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

References

- Academies NRCotN. Guidelines for the care and use of mammals in neuroscience and behavioral research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball KT, Budreau D, Rebec GV. Context-dependent behavioural and neuronal sensitization in striatum to MDMA (ecstasy) administration in rats. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;24:217–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball KT, Wellman CL, Fortenberry E, Rebec GV. Sensitizing regimens of MDMA (ecstasy) elicit enduring and differential structural alterations in the brain motive circuit of the rat. Neuroscience. 2009;160:264–274. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball KT, Wellman CL, Miller BR, Rebec GV. Electrophysiological and structural alterations in striatum associated with behavioral sensitization to (+/−)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy) in rats: role of drug context. Neuroscience. 2010;171:794–811. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafters RI. Hyperthermia following MDMA administration in rats: effects of ambient temperature, water consumption, and chronic dosing. Physiol Behav. 1995;58:877–882. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitzemann RJ, Tseng LF, Hitzemann BA, Sampath-Khanna S, Loh HH. Effects of withdrawal from chronic amphetamine intoxication on exploratory and stereotyped behaviors in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1977;54:295–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00426579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Duffy P, White SR. MDMA elicits behavioral and neurochemical sensitization in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18:469–479. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolta MG, Shreve P, De Souza V, Uretsky NJ. Time course of the development of the enhanced behavioral and biochemical responses to amphetamine after pretreatment with amphetamine. Neuropharmacology. 1985;24:823–829. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(85)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leith NJ, Kuczenski R. Two dissociable components of behavioral sensitization following repeated amphetamine administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1982;76:310–315. doi: 10.1007/BF00449116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary AC, Bankson MG, Cunningham KA. Pharmacological studies of the acute and chronic effects of (+)-3,4-mehylenedioxymethamphetamine on locomotor activity: role of 5-hydroxytryptamine1A and 5-hydroxytryptamine1B/1D receptors. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1999;290:965–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson PE, Camp DM, Robinson TE. Time course of transient behavioral depression and persistent behavioral sensitization in relation to regional brain monoamine concentrations during amphetamine withdrawal in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1991;103:480–492. doi: 10.1007/BF02244248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos M, Goni-Allo B, Aguirre N. Studies on the role of dopamine D1 receptors in the development and expression of MDMA-induced behavioral sensitization in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2004;177:100–110. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1937-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebec GV, Bashore TR. Critical issues in assessing the behavioral effects of amphetamine. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1984;8:153–159. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(84)90030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS. Behavioral and neurochemical correlates of repeated d-amphetamine administration. Advances in Biochemical Psychopharmacology. 1975;13:247–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS, Mandell AJ. Long-term administration of d-amphetamine: progressive augmentation of motor activity and stereotypy. Pharmacology Biochemistry & Behavior. 1974;2:249–255. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(74)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanos LJ, Yamamoto BK. Acute and subchronic effects of methylenedioxymethamphetamine [(±)MDMA] on locomotion and serotonin syndrome behavior in the rat. Pharmacology Biochemistry & Behavior. 1989;32:835–840. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J, Badiani A. Tolerance and sensitization to the behavioral effects of drugs. Behavioral Pharmacology. 1993;4:289–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]