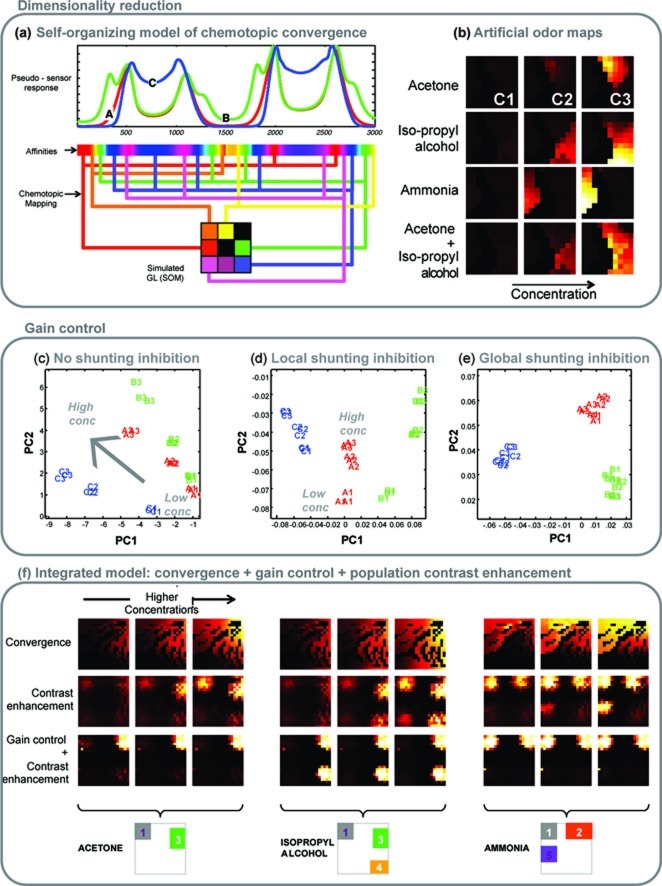

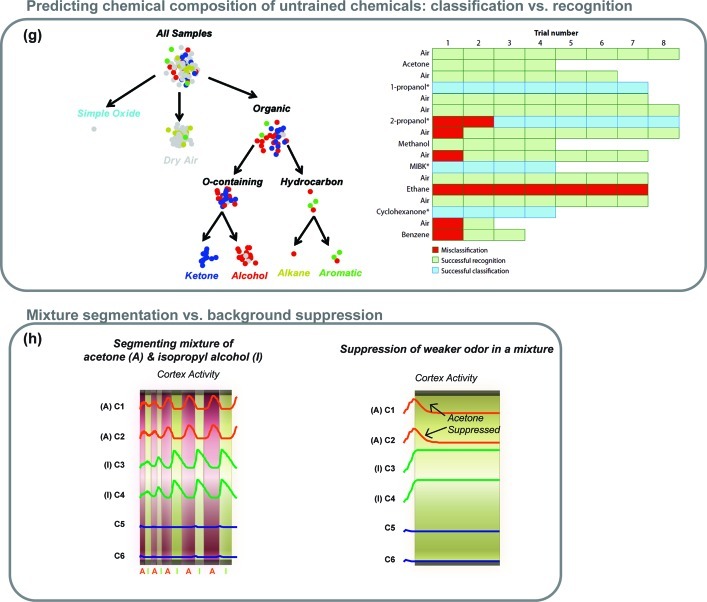

Figure 5.

Neuromorphic approaches for signal processing. (a) Illustration of chemotopic pseudosensor receptor neurons (top) converging onto a simulated glomerular lattice (bottom). The responses of the sensor to three analytes (labeled A, B, and C) are used to define the pseudosensor’s affinities (shown as a color bar). Pseudosensors with similar affinities project to the same artificial glomerulus (a node in the self-organizing map) as a result of chemotopic convergence, as in a biological glomerulus. Activity across the simulated glomerular lattice forms a spatially distributed representation of the odor, and can be considered an artificial odor map. (Reprinted from ref (97)). (b) Artificial glomerular images generated from an experimental database of temperature-modulated metal-oxide semiconductor sensors exposed to acetone, isopropyl alcohol, and ammonia at three different concentrations levels (C1–3). As has been observed in the olfactory bulb, increasing concentrations of odorant expanded the area of activation at the odor-specific locus. Bottom row: Odor maps generated from the sensor array showing response to a mixture of acetone and isopropyl alcohol at three concentrations. The binary mixture had an additive effect and generated odor maps that activated regions of the lattice corresponding to both component odors. More complex mixture responses have been reported in vivo. (Reprinted with permission from ref (7). Copyright 2006 IEEE). (c–e) Various forms of shunting inhibition can be employed to either compress or remove concentration information. Principal component analysis (PCA) scatterplots showing responses of a temperature-modulated sensor to three analytes presented at three concentrations (A1, lowest concentration of analyte A; C3, highest concentration of analyte C). PCA plots compare the odor identity and intensity distributions following (c) chemotopic convergence (no shunting inhibition), (d) normalization using a shunting inhibition model with local connections, and (e) normalization using a shunting inhibition model with global connections. (f) Combining biomimetic processing steps can further enhance odor discrimination. Artificial odor maps after chemotopic convergence (top row), processed with an additive model of the olfactory bulb with center-surround inhibition (middle row), and integrated OB network with shunting inhibition and center-surround inhibition (third row). Outlines of steady-state active regions in the artificial odor maps corresponding to different analytes are highlighted below the plots. (Reprinted from ref (97)). (g) Mimicking the biological approach of refining odor representation over time, a hierarchical scheme that performed initial discrimination between broad chemical classes (e.g., contains oxygen) followed by finer refinements using additional data into subclasses (e.g., ketones vs alcohols) and, eventually, specific compositions (e.g., ethanol vs methanol) is shown. Left panel: Graphical view of the traversal of each measurement through the hierarchy. The chemical family of the analyte present during measurement is color-coded: gray = dry air, cyan = simple oxide, red = alcohol, blue = ketone, yellow = alkane, and green = aromatic. Right panel: Chart of the accuracy of placement of each measurement into its proper category: green box = correct recognition, blue box = correct classification, and red = incorrect placement. Analytes not included during the training phase are indicated with an asterisk. The order of analyte exposure during the test phase is as shown, progressing from left to right and then top to bottom (trials 1–8 were air exposures, trials 9–13 were acetone exposures, and so on). (Reprinted with permission from ref (88). Copyright 2008 American Chemical Society). (h) Both mixture segmentation and background suppression can be achieved by a model of olfactory bulb–cortex interactions. In this model, the olfactory bulb sends nontopographic and many-to-many projections to the olfactory cortex such that cortical neurons detect combinations of co-occurring molecular features of the odorant and therefore function as coincidence detectors. The associational connections within the cortex are established through correlative Hebbian learning, such that cortical neurons that respond to at least one common odor have purely excitatory connections between them, and neurons that encode for different odors (no common odor) have purely inhibitory connections between them. The excitatory lateral connections perform pattern completion of degraded inputs from the bulb, whereas the inhibitory connections introduce winner-take-all competition among cortical neurons. Two types of feedback connection were investigated: (i) Anti-Hebbian update forms feedback connections such that the resulting centrifugal input from the model cortex inhibits bulb neurons responsible for the cortical response, resulting in the temporal segmentation of binary mixtures (left panel). (ii) Hebbian update on the other hand retains only those connections between cortical neurons and bulb neurons that respond to different odors. The resulting feedback from the cortex inhibits bulb neurons other than those responsible for the cortical response, causing cortical activity to resonate with OB activity and lock onto a particular odor and suppress the background/weaker odor (right panel). (Reprinted with permission from ref (91). Copyright 2005 IEEE).