Abstract

Digital replantation has become a well-established technique among reconstructive hand surgeons. Numerous replantation centers around the world have published series with impressive survival rates. The ultimate goal of replantation is the restoration of normal hand or digital function; thus, replantation success is not solely related to the outcome of the microvascular anastomosis, but also to the adequacy of bone, tendon, skin, and nerve repairs. In this manuscript, we review the literature on upper extremity and digital replantation from its historical background to current surgical outcomes, outlining surgical indications and contraindications, and the preoperative, operative, and postoperative management of these patients.

Keywords: Replantation, Amputation, Digital, Upper extremity

Introduction

The first documented medical report regarding replantation occurred during the Middle Ages, when Guy de Chauliac, one of the most prominent surgeons of the medieval era, reported, in his famous work Chirugia magna (1363), that reattachment of an amputated body part was not possible. During the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, case reports of nose reattachment were published by European surgeons based on nose reconstruction techniques developed in India, where criminals and inhabitants of defeated cities were commonly punished with amputation of the nose. It was not until the 1800s that digital replantation became a possibility. William Balfour in the Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal of 1814 published the first medical report of a digital reattachment. Balfour successfully repaired his son’s index, middle, and long fingers, which were partially amputated at the mid-distal phalanx [24]. These replantations were performed without vascular anastomosis; thus, we would suspect these fingers survived as composite grafts; however, the theory of spontaneous recanalization occurring in composite grafts would not be published until 1964 by Douglas and Foster [15].

Experimental work in replantation and vascular anastomosis techniques pioneered simultaneously by Halsted, Hopfner, and Carrel in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries supplied the basic principles of the new field of vascular surgery. Alexis Carrel, who won the Noble Prize in 1912 for his development of the vascular anastomosis technique, performed the first extremity replantation in a complete amputated canine hind limb in 1906 [8, 24, 27]. With further technical advancements in suture material and surgical instruments, primarily the operating room microscope, replantation became a standard laboratory procedure. It is during this period of time that Harry Buncke is credited with developing the first set of microsurgical instruments, microsutures (constructed from a single strand of cocoon silk), and microsurgical needles [41].

It was not until the 1960s that clinical replantation became a reality. Ronald Malt replanted the right arm of a 12-year-old boy after an above-elbow amputation from a train accident in 1962, which was the first report of a successful arm replantation in a patient [27]. The development of microsurgical vascular anastomosis by Jacobson and Suarez in 1960 allowed the replantation of smaller parts of the body, such as the fingers, thumbs, ears, scalp, lips, and genitalia [1, 13, 21, 23, 25, 31, 32, 53]. A new era in reconstructive surgery had begun. Kleinert et al. performed the first digital arteries anastomosis in the revascularization of a partially amputated thumb in 1963 [23]. The first replantation of a complete digit amputation using microvascular anastomosis was performed by Komatsu and Tamai in 1965 [25]. Simultaneous great advancements in the replantation field were being achieved in Shangai, China, as reported in 1973 by the American Replantation Mission Team. The Chinese shared their large experience with the rest of the world, including pioneer techniques in cross replantation, transpositional replantation, and toe-to-thumb transfers [1, 35].

During the decades of the 1970s and 1980s, with microsurgical techniques becoming well established among reconstructive surgeons, numerous replantation centers around the world were reporting series with impressive survival rates higher than 80%, or even higher than 90% in selected patients [4, 12, 22, 28, 35, 40, 42, 45]. In the USA, Buncke et al. contributed with great experimental and clinical work in this “amazement phase” of replantation surgery [6, 7]. As stated by the Chinese surgeons, “survival without restoration of function is not success” [1], and the most current literature is focused on long-term functional outcome after replantation [5, 14, 30, 50, 52, 59]. The ultimate goal and real benefit from replantation is determined by functional recovery and is related not only to the success of the microvascular anastomosis, but also to the adequacy of bone, tendon, skin, and nerve repairs.

Indications and Contraindications for Upper Extremity and Digital Replantation

Not all patients benefit from or are candidates for replantation. In a traumatized patient, priority must be given to life-threatening injuries that demand immediate attention. Replantation is only considered in a stable patient. The decision to replant is often multifaceted, involving economic, social, and psychological factors, in combination with the general health condition of the patient and the tissues to be replanted. The expected return of function and a realistic outcome from the procedure need to be evaluated by the surgeon and discussed with the patient. The final decision is usually not made until inspection of the stump and amputated parts under the microscope in the operating room. What appears to be a severely damaged limb or digit with extensive tissue loss may be only a disarrangement of the tissues with minimal loss once fully explored in the operating room. Every effort should be made to minimize the time interval between amputation and replantation, and hypothermic preservation of the amputated part is the standard of care and should be established to avoid irreversible degeneration of tissue cells [1, 12, 30, 34, 35, 40, 55].

Upper extremity amputations at the level of the wrist and hand should be replanted unless there are absolute life-threatening contraindications. Replantation of the proximal arm should be attempted in order to at least preserve the function of the elbow. Some controversy still remains in regards to indications for digital replantation. Indications for digital replantation include (1) amputated thumbs, (2) multiple digits, (3) single digit distal to the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon, and (4) all digital amputations in children. The decision to replant a proximal amputation in a single digit is debatable among authors and a special circumstance is required, such as left ring finger in a female, occupational requirements, or religious and ethnic preference. Contraindications for digital replantation include severe crushing injury, multiple level injuries in the same digit, massive contamination, frozen parts, prolonged normothermic ischemia time, and parts preserved in non-physiologic solutions. Severe comminuted intra-articular fractures might be considered a contraindication for replantation given its presumed poor functional outcome. Complete ring avulsion injuries can be a contraindication for replantation, although some authors believe it still can be attempted with judicious use of venous grafts, unless the PIP joint is damaged or the proximal phalanx is fractured [22, 28–30, 34, 42, 43, 45, 50, 55]. Predictive signs of severe damage to the neurovascular bundle and unsuccessful replantation include the “red line” and “ribbon” signs, which suggest a wide zone of intimal injury [48] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Digital artery in an avulsed thumb. The artery shows evidence of “the ribbon sign”; twisting of the artery is thought to be suggestive of significant intimal injury to the vessel and is a poor prognostic sign for replant success

Temporary ectopic implantation of an undamaged amputated part can be considered in specific salvage procedure in a mutilated upper extremity in a special circumstance when the distal part is relatively intact, but the proximal stump presents with extensive soft tissue injury or massive contamination, which requires aggressive debridement and precludes immediate replantation [2, 10, 18].

Preoperative Management

The preservation of the amputated part is key to successful replantation. General consensus in the literature regarding reliable ischemia times for a successful replantation are 12 h of warm and 24 h of cold ischemia for digits and 6 h of warm and 12 h of cold ischemia for major upper extremity replantation. The amputated part should be immersed in saline solution or wrapped in a saline-moistened gauze immediately, placed in a sealed plastic bag, and submerged in ice saline solution (approximately at 4°C). Minimizing warm ischemia is crucial, mainly when replanting major body parts with significant muscular mass. Freezing and direct immersion in water of the severed part should be avoided [46, 49]. Reports of successful digital replantation after 94 h of cold ischemia and 33 h of warm ischemia as well as successful hand replantation after 54 h of cold ischemia have been published in the literature [11, 37, 54]. Replantation after prolonged period of ischemia such as these case reports should only be attempted in selected cases.

At arrival in the replantation center, X-rays and pictures of the stump and amputated parts are obtained. Prophylactic antibiotics and tetanus status update are indicated in addition to general resuscitative measures. Hemostasis of the amputated stump should be achieved with external compression and one should avoid clamping vessels as this produces additional vessel damage. While the patient is evaluated for possible replantation, the amputated part should be taken immediately to the operating room to be examined under an operating microscope where important structures can be dissected, isolated, and tagged [22]. Until the time of revascularization, the amputated part should be kept and preserved at 4°C in the operating room. Amputated parts unsuitable for replantation should not be discarded, but instead evaluated for its use as a spare part. In a situation of multiple digital amputations, a digit judged to be non-replantable could still be useful for digital transposition or as source for nerve graft, skin graft, arterial graft, or bone graft [30].

Operative Management

Regional anesthesia alone or in combination with general anesthetic for digital and major replantation provides the benefit of sympathetic blockade, which optimizes vasodilatation and facilitates vascular anastomosis [22, 40, 55]. Ideally, two teams of microsurgeons should be simultaneously working on preparing the stump and the amputated part. Numerous authors have published detailed articles on surgical techniques for major upper extremity and digital replantation. Here we will summarize the operative sequence for these procedures [1, 7, 9, 12, 16, 22, 25, 27, 34, 35, 40, 42, 55]. The exact order of repair in replantation is dictated by surgeon preference and individualized for every patient, but some general rules should be acknowledged.

Major Upper Extremity Replantation

Preservation of the amputated part is critical on major upper extremity replantation, and cooling should continue until arterial anastomosis is completed [34, 42]. Some authors recommend perfusion of the amputated part prior to replantation with heparinized saline to assure vascular patency, to rule out other vascular injuries, to eliminate metabolite breakdown products from prolonged ischemia, and to clear possible thrombi [9, 16, 42].

Under tourniquet control, the stump and the amputated part undergo aggressive debridement. Removing all devitalized tissue is key in order to avoid local necrosis and infection that could lead to replantation failure. Bone shortening is performed to compensate for the loss of soft tissue, allowing re-approximation of skin, tendons, muscle, and, mainly, neurovascular structures with minimal tension [1, 55]. Several techniques are described for bone fixation, including Kirschner pins, intramedullary pins, plates, and screws, and all have specific indications for different situations and patients [34]. In the volar aspect of the limb, the muscle and tendons are not repaired until completion of vascular anastomosis. On proximal amputations, deep muscles and tendons are repaired first to optimize vascular anastomosis. On distal amputations, extensor tendons are repaired first with subsequent venous repair [34]. Venous followed by arterial anastomosis is then performed, in order to minimize blood loss and prevent a bloody surgical field [55]. A ratio of 2 veins to 1 artery anastomosis is required to improve the outflow and increase the chances of survival.

In a situation of prolonged ischemia, arterial anastomosis can be performed first, or just after the repair of one vein. Vein grafts should be used liberally when the anastomosis is under tension or there is questionable viability of vessel ends [9, 34, 42]. If necessary, a commercial vascular shunt can be used to re-establish arterial flow within the amputated part. This allows the part to reperfuse while bone fixation is completed or while debridement is continued. Early shunting, while beneficial for tissue oxygenation, can result in excessive blood loss and obstruction of visualization of important structures; thus, its use should be reserved for cases when the warm ischemia time has been prolonged.

Muscles and tendon are reconnected and followed by primary nerve repair with epineural suturing. In cases with gross nerve deficiency, a nerve grafting or nerve pedicle flap may be required. Primary repair is always the goal to avoid a second procedure [34]. Skin should be loosely approximated, and the need for a skin graft or local should be evaluated [1]. The need of a decompressive fasciotomy should be always considered, depending on the ischemia time and the amount of tissue damage. Fasciotomies are found to be necessary in the majority of proximal replantations [12, 34, 42] (Fig. 2).

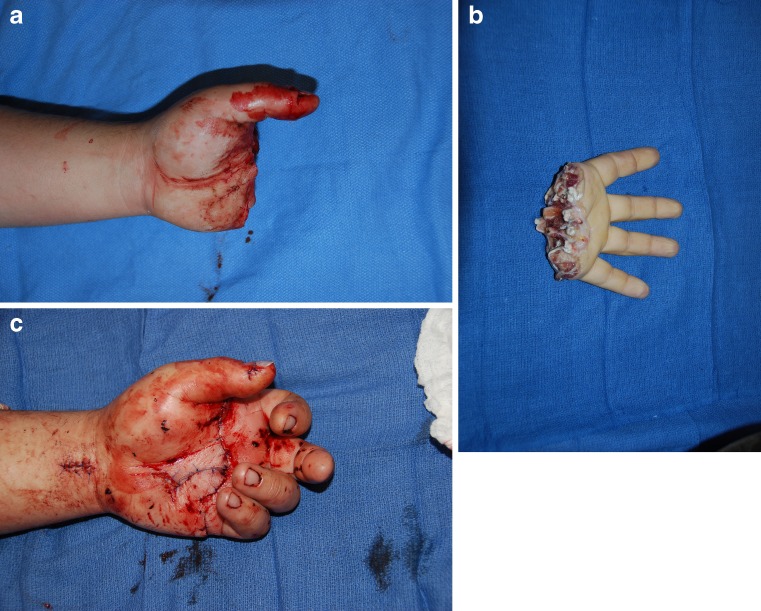

Fig. 2.

a–c Replantation of a metacarpal hand after industrial amputation at a meat processing plant in 21-year-old man

Digital Replantation

Bruner incisions allow broad exposure for digital replantation. Lateral incisions have also been proposed, but they are difficult to close without compressing the vasculature and can leave the vessel sometimes exposed [30, 33]. The digital nerves and vessels are identified and tagged after meticulous debridement of devitalized tissues under tourniquet control. Bone shortening (between 0.5 and 1 cm) allows soft tissue repair and assures a tension-free neurovascular anastomosis. Skeletal fixation and alignment should be secure to allow early postoperative mobilization and future union. There are several bone fixation methods (Kirschner wires, intraosseous wires, intramedullary wires, tetrahedral wires, pins, plates, and screws) and multiple combinations among them. When amputation occurs through the joint, arthrodesis should be performed. Periosteum and soft tissues should be carefully repaired to prevent tendon adhesions and a secondary procedure [30, 40, 44, 56]. From a dorsal approach, the extensor tendons can be repaired first. The veins are repaired next, unless there is prolonged time of ischemia or difficulty in identifying the veins. At least two veins should be repaired and vein graft is rarely needed [1, 30]. Early arterial repair is advocated by some authors in order to re-establish early perfusion of the tissues, eliminate metabolite breakdown products generated from tissue ischemia, and facilitate identification of the veins [7, 22, 40, 44].

From a palmar approach, the flexor tendons should be repaired before the neurovascular anastomosis. Facilitated by bone shortening, a direct repair of the tendon should be attempted in order to avoid a graft or tendon rods [30]. Repair of both the profundus and superficialis tendons has been associated with improved postoperative motion when compared to single tendon fingers [36]. Following tendon repair, arterial anastomosis should be performed without tension and using a vein graft liberally when indicated [3, 6, 44]. Vein grafts are commonly used in thumb replantation and ring avulsion and can be harvested from the wrist or forearm [19, 38, 43]. Meticulous debridement should be done to assure anastomosis of healthy intima in both ends [30]. Bathing arterial anastomosis site with papaverine, lidocaine, or magnesium sulfate has been shown to improve patency rates and survival in animal models [39]. The more vessels repaired, the better the result expected, and one should aim for a 2:1 vein to artery ratio.

Digital nerve reconstruction should also be done primarily with epineural sutures. Nerve grafts are sometimes necessary and harvested from the forearm or from a digit non-suitable for replantation. Skin should be closed avoiding tension and sometimes are left partially opened but without vessel exposure. Skin grafts can be used to cover small defects but contraindicated when using systemic anticoagulation. Large defects may need flap coverage [30] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

a–c Successful replantation of a thumb amputation at the level of the proximal phalanx, seen here at the time of injury and 3 weeks after replantation. Skeletal shortening facilitated skin closure; however, long segment vein grafts were required for both arterial and venous reconstruction. A dorsal hand flap provided coverage of the vein grafts. The donor site was covered with a full-thickness skin graft

Postoperative Management

In the postoperative course of replantation, peripheral vasospasm should be prevented and complications detected and addressed early. The room should be kept warm and the patient well hydrated. In order to minimize adrenergic response and vasoconstriction, pain and anxiety control are very important, especially in the pediatric population. Smoking should be prohibited to prevent hypoxia, reduction of peripheral blood flow, and thrombogenesis [47]. The replanted part should be kept at the level of the heart or slightly higher. Dressings should be loosely applied, without any tension or risk of constriction. Minimal dressing facilitates frequent inspection. Skin color, tactile temperature, tissue turgor, and capillary refill should be monitored closely and frequently. More objective criteria for evaluation of the replanted part can be obtained with thermometric monitoring, an easy and reliable method to predict the viability of the tissue [26].

Perioperative anticoagulation protocols for digital replantation with dextran, heparin, and aspirin vary according to the surgeon and institution, with no prospective randomized data to support a standard regimen of any of these medications. Generally, no postoperative anticoagulation is required for uncomplicated major replantation [34]. Antibiotics should be continued for approximately 1 week.

Early recognition of vascular compromise is essential for the hand surgeon and resident staff. Arterial and venous occlusion will lead to failure if not treated quickly. External compression should be ruled out first by removing the dressing and releasing sutures. In patients with arterial obstruction, the finger will appear pale or dusky. There will be a decrease in pulse oximetry readings within the finger and temperature may be decreased in comparison to the other digits or hand. Tissue turgor within the finger tip will be decreased, and there will be an absence of bleeding when the finger is poked with a needle. Non-surgical attempts at improving arterial perfusion to the replanted finger may include optimizing blood pressure, placing the part in a dependent position, and systemically anticoagulating the patient. Sympathetic block is also part of the arsenal of some authors to combat vasospasm [35]. If these methods do not rapidly restore perfusion then re-exploration, re-anastomosis, or venous grafting should be performed immediately.

In patients with venous obstruction, the finger is blue, purple, and swollen. There may be excessive bleeding from the wound edges. In such cases, nail bed resection, fingertip incision, and leech therapy as a salvage therapy are options to improve outflow. Venous occlusion is more detrimental to the long-term survival of the replanted part than arterial obstruction, due to the accumulation of toxins and breakdown of metabolites from the ischemic tissues and should be treated urgently, avoiding at all costs late re-exploration, when disruption of new vital new capillary connections will be inevitable [30]. Bleeding leading to hematoma formation and external compression of the vessels also puts the replant at risk, which should be addressed holding systemic anticoagulation and transfusing blood products if needed.

Surgical Outcome

Replantation survival rates of 80% to 90% have been described in selected reports [4, 12, 22, 28, 35, 40, 42, 45, 51]. Improving survival rates are due to better patient selection, improved microsurgical technique and equipment, and the liberal use of vein grafts. Replantation survival rates are directly associated to the experience and skill of the surgical team and selection of the patient population. As stated earlier, the ultimate goal and real benefit from replantation is determined by functional recovery and is related not only to the success of the microvascular anastomosis, but to the adequacy of bone, tendon, and nerve repairs. Different criteria to evaluate functional recovery after replantation have been described by many authors. Kleinert et al. suggest that functional criteria should include sensibility ratings, grip strength, range of motion, the absence of cold intolerance, and the return to work. Kleinert et al. found return to work to be associated more with personal motivation than type or level of injury [22].

With regard to overall sensory recovery following digital replantation, Tamai reported two-point discrimination sensibility less than 15 mm in 70% of his patients [42]. Sensory recovery has been shown to be better following replantation where the mechanism was sharp cuts rather than avulsion injury. In Glickman and Mackinnon’s review of over 400 digital replants, they found that the average static two-point recovery in thumbs replanted following a clean cut was 9.3 mm compared to 12.1 mm in those suffering a crush/avulsion-type mechanism. Fingers recovered on average 8 mm of static two-point recovery and 15 mm in crush/avulsion-type mechanisms. Overall, only 61% of thumbs and 54% of fingers recovered useful two-point discrimination [17].

With regard to overall finger motion, Ross and colleagues evaluated 48 patients with 103 digital replantations and noted that the average total active motion of the fingers was 129°. Replantation in zones 1 and 5 fared better than those in zones 2 through 4. Avulsions had poorer outcomes [36]. Buncke et al. believe that sensibility and tendon gliding are the most critical factors for a successful functional recovery and describe stiffness caused by flexor tendon adhesion to be the most common cause of unsatisfactory functional result after replantation [7]. Meticulous tenorrhaphy is essential to avoid postoperative adhesion or rupture and a secondary procedure [57]. For those patients who do develop significant adhesions following replantation, tenolysis has been found to significantly improve function [58].

Subjective criteria using a patient-centered questionnaire (The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score) was used by Dabernig et al. to evaluate functional outcomes after replantation. DASH scores following thumb replantation averaged 10, single finger replants averaged 11.2, and multiple finger amputations where at least one finger was replanted averaged 16.1. These low scores emphasize the perception of the patient about the success of replantation [14]. Comparative studies evaluating the DASH scores following single finger replantation and amputation have found better DASH scores in those patients undergoing replantation [20].

Despite these encouraging functional results, several problems still remain following replantation, which include the poor return of intrinsic muscle function in injuries occurring at the wrist and proximal [37]. In addition, persistent cold intolerance is a complaint of the majority of replanted patients [22].

Conclusion

Upper extremity and digital replantation should be a procedure within the realm of all hand surgeons. The viability of the replanted part is guaranteed by a successful vessel anastomosis, while the quality of the bone, tendon, nerve, and skin repair will determine the overall functional success of the replanted parts. Repair of all structures at the time of the primary procedure should be attempted, as secondary surgery is technically difficult. Future advancements should focus on improving the sensation, decreasing cold intolerance, and maximizing tendon motion in an effort to return the patient to their preoperative functional state.

Contributor Information

Marco Maricevich, Phone: +1-507-2848240, FAX: +1-507-5387288, Email: maricevich.marco@mayo.edu.

Brian Carlsen, Phone: +1-507-2844685, FAX: +1-507-2845994, Email: carlsen.brian@mayo.edu.

Samir Mardini, Phone: +1-507-2844685, FAX: +1-507-2845994, Email: mardini.samir@mayo.edu.

Steven Moran, Phone: +1-507-2844685, FAX: +1-507-2845994, Email: moran.steven@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.American Replantation Mission to China. Replantation surgery in China. Report of the American Replantation Mission to China. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;52(5):476–89. [PubMed]

- 2.Bajec J, Grossman JA, Gilbert D, et al. Upper extremity preservation before replantation. J Hand Surg [Am] 1987;12(2):321–2. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(87)80301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biemer D. Vein grafts in microvascular surgery. Br J Plast Surg. 1977;30(3):197–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braga-Silva J. Single digit replantations in ambulatory surgery. 85 cases. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2001;46(2):74–83. doi: 10.1016/S0294-1260(01)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks D, Buntic RF, Kind GM, et al. Ring avulsion: injury pattern, treatment, and outcome. Clin Plast Surg. 2007;34(2):187–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buncke HJ, Alpert B, Shah KG. Microvascular grafting. Clin Plast Surg. 1978;5(2):185–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buncke HJ, Alpert BS, Johnson-Giebink R. Digital replantation. Surg Clin North Am. 1981;61(2):383–94. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)42388-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrel A, Guthrie CC. Results of a replantation of a thigh. Science. 1906;23:393. doi: 10.1126/science.23.584.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen ZW, Zeng BF. Replantation of the lower extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 1983;10(1):103–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chernofsky MA, Sauer PF. Temporary ectopic implantation. J Hand Surg [Am] 1990;15(6):910–4. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(90)90014-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu HY, Chen MT. Revascularization of digits after thirty-three hours of warm ischemia time: a case report. J Hand Surg [Am] 1984;9A(1):63–7. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung-Wei C, Yun-Qing Q, Zhong-Jia Y. Extremity replantation. World J Surg. 1978;2(4):513–24. doi: 10.1007/BF01563690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen BE, May JW, Jr, Daly JS, et al. Successful clinical replantation of an amputated penis by microneurovascular repair. Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59(2):276–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dabernig J, Hart AM, Schwabegger AH, et al. Evaluation outcome of replanted digits using the DASH score: review of 38 patients. Int J Surg. 2006;4(1):30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglas B, Foster JH. Union of severed arterial trunks and canalization without sutures or prosthesis. Ann Surg. 1964;157:944. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196306000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gayle LB, Lineaweaver WC, Buncke GM, et al. Lower extremity replantation. Clin Plast Surg. 1991;18(3):437–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glickman LT, Mackinnon SE. Sensory recovery following digital replantation. Microsurgery. 1990;11(3):236–42. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920110311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godina M, Bajec J, Baraga A. Salvage of the mutilated upper extremity with temporary ectopic implantation of the undamaged part. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78(3):295–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton RB, O'Brien BM, Morrison A, et al. Survival factors in replantation and revascularization of the amputated thumb—10 years experience. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;18(2):163–73. doi: 10.3109/02844318409052833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hattori Y, Doi K, Ikeda K, et al. A retrospective study of functional outcome after successful replantation versus amputation closure for single finger tip amputation. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(5):811–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobson JH, Suarez EL. Microsurgery and anastomosis of the small vessels. Surg Forum. 1960;11:243. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleinert HE, Jablon M, Tsai TM. An overview of replantation and results of 347 replants in 245 patients. J Trauma. 1980;20(5):390–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleinert HE, Kadsan ML, Romero JL. Small blood vessel anastomosis for salvage of severely injured upper extremity. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1963;45:788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kocher MS. History of replantation: from miracle to microsurgery. World J Surg. 1995;19(3):462–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00299192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komatsu S, Tamai S. Successful replantation of a completely cut-off thumb: case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42:374–7. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196810000-00021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu SY, Chiu HY, Lin TW, et al. Evaluation of survival in digital replantation with thermometric monitoring. J Hand Surg [Am] 1984;9(6):805–9. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malt RA, McKhann C. Replantation of several arms. JAMA. 1964;189:716–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.1964.03070100010002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.May JW, Jr, Toth BA, Gardner M. Digital replantation distal to the proximal interphalangeal joint. J Hand Surg [Am] 1982;7(2):161–6. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(82)80081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer VE. Hand amputations proximal but close to the wrist joint: prime candidates for reattachment (long-term functional results) J Hand Surg [Am] 1985;10(6 Pt 2):989–91. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(85)80020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison WA, McCombe D. Digital replantation. Hand Clin. 2007;23(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nahai F, Hayhurst JW, Salibian AH. Microvascular surgery in avulsive trauma to the external ear. Clin Plast Surg. 1978;5(3):423–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nahai F, Hurteau J, Vasconez LO. Replantation of an entire scalp and ear by microvascular anastomoses of only 1 artery and 1 vein. Br J Plast Surg. 1978;31(4):339–42. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(78)90122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nissenbaum M. A surgical approach for replantation of complete digital amputations. J Hand Surg [Am] 1980;5(1):58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(80)80045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Brien BM. Replantation surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 1974;1(3):405–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Replantation of severed fingers. Clinical experiences in 217 cases involving 373 severed fingers. Chin Med J (Engl). 1975;1(3):184–96. [PubMed]

- 36.Ross DC, Manktelow RT, Wells MT, et al. Tendon function after replantation: prognostic factors and strategies to enhance total active motion. Ann Plast Surg Aug. 2003;51(2):141–6. doi: 10.1097/01.SAP.0000058499.74279.D8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russell RC, O'Brien BM, Morrison WA, et al. The late functional results of upper limb revascularization and replantation. J Hand Surg [Am] 1984;9(5):623–33. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlenker JD, Kleinert HE, Tsai TM. Methods and results of replantation following traumatic amputation of the thumb in sixty-four patients. J Hand Surg [Am] 1980;5(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(80)80046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swartz WM, Brink RR, Buncke HJ., Jr Prevention of thrombosis in arterial and venous microanastomoses by using topical agents. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58(4):478–81. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197610000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamai S. Digit replantation. Analysis of 163 replantations in an 11 year period. Clin Plast Surg. 1978;5(2):195–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamai S. The history of microsurgery. In: Tamai S, Usui M, Yoshizu T, editors. Experimental and clinical reconstructive microsurgery. Tokyo: Springer; 2003. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamai S. Twenty years' experience of limb replantation—review of 293 upper extremity replants. J Hand Surg [Am] 1982;7(6):549–56. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(82)80100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsai TM, Manstein C, DuBou R, et al. Primary microsurgical repair of ring avulsion amputation injuries. J Hand Surg [Am] 1984;9A(1):68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urbaniak JR, Hayes MG, Bright DS. Management of bone in digital replantation: free vascularized and composite bone grafts. Clin Orthop Jun. 1978;133:184–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Urbaniak JR, Roth JH, Nunley JA. The results of replantation after amputation of a single finger. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(4):611–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Usui M, Ishii S, Muramatsu I, et al. An experimental study on "replantation toxemia". The effect of hypothermia on an amputated limb. J Hand Surg [Am] 1978;3(6):589–96. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(78)80011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Adrichem LN, Hovius SE, van Strik R, et al. The acute effect of cigarette smoking on the microcirculation of a replanted digit. J Hand Surg [Am] 1992;17(2):230–4. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(92)90397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Beek AL, Kutz JE, Zook EG. Importance of the ribbon sign, indicating unsuitability of the vessel, in replanting a finger. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61(1):32–5. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197801000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.VanGiesen PJ, Seaber AV, Urbaniak JR. Storage of amputated parts prior to replantation—an experimental study with rabbit ears. J Hand Surg [Am] 1983;8(1):60–5. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(83)80055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vanstraelen P, Papini RP, Sykes PJ, et al. The functional results of hand replantation. The Chepstow experience. J Hand Surg [Br] 1993;18(5):556–64. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(93)90003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waikakul S, Sakkarnkosol S, Vanadurongwan V, Un-nanuntana A. Results of 1018 digital replantations in 552 patients. Injury. 2000;31(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(99)00196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walaszek I, Zyluk A. Long term follow-up after finger replantation. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33(1):59–64. doi: 10.1177/1753193407088499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walton RL, Beahm EK, Brown RE, et al. Microsurgical replantation of the lip: a multi-institutional experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(2):358–68. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199808000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei FC, Chang YL, Chen HC, et al. Three successful digital replantations in a patient after 84, 86, and 94 hours of cold ischemia time. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82(2):346–50. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198808000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weiland AJ, Villarreal-Rios A, Kleinert HE. Replantation of digits and hands: analysis of surgical techniques and functional results in 71 patients with 86 replantations. J Hand Surg [Am] 1977;2(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(77)80002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whitney TM, Lineaweaver WC, Buncke HJ, et al. Clinical results of bony fixation methods in digital replantation. J Hand Surg [Am] 1990;15(2):328–34. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(90)90118-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamauchi S, Nomura S, Yoshimura M, et al. A clinical study of the order and speed of sensory recovery after digital replantation. J Hand Surg [Am] 1983;8(5 Pt 1):545–9. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(83)80122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu JC, Sheih SJ, Lee JW, et al. Secondary procedures following digital replantation and revascularization. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56(2):125–8. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1226(03)00033-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zumiotti A, Ferreira MC. Replantation of digits: factors influencing survival and functional results. Microsurgery. 1994;15(1):18–21. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920150107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]