Abstract

Background:

Hypertension is the most prevalent non-communicable disease causing significant morbidity/mortality through cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and renal complications.

Objectives:

This community-based study tested the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions in preventing/controlling hypertension.

Materials and Methods:

This is a cross-over randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the earlier RCT (2007) of non-pharmacological interventions in hypertension, conducted in the urban service area of our Institute. The subjects, prehypertensive and hypertensive young adults (98 subjects: 25, 23, 25, 25 in four groups) were randomly allotted into a group that he/she had not belonged to in the earlier RCT: Control (New Group I), Physical Exercise (NG II)-brisk walking for 50 to 60 minutes, three to four days/week, Salt Intake Reduction (NG III) to at least half of their previous intake, Yoga (NG IV) for 30 to 45 minutes/day, five days/week. Blood pressure was measured before and after eight weeks of intervention. Analysis was by ANOVA with a Games-Howell post hoc test.

Results:

Ninety-four participants (25, 23, 21, 25) completed the study. All three intervention groups showed significant reduction in BP (SBP/DBP mmHg: 5.3/6.0 in NG II, 2.5/2.0 in NG III, and 2.3/2.4 in NG IV, respectively), while the Control Group showed no significant difference. Persistence of significant reduction in BP in the three intervention groups after cross-over confirmed the biological plausibility of these non-pharmacological interventions. This study reconfirmed that physical exercise was more effective than Salt Reduction or Yoga. Salt Reduction, and Yoga were equally effective.

Conclusion:

Physical exercise, salt intake reduction, and yoga are effective non-pharmacological methods for reducing blood pressure in young pre-hypertensive and hypertensive adults.

Keywords: Cross-over randomized controlled trial, hypertension, non-pharmacological interventions

Introduction

Hypertension is the most prevalent non-communicable disease in India.(1) Globally, 7.1 million deaths (~12.8% of total deaths) and 64.3 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (4.4% of global total) are estimated to be due to hypertension, the prevalence being 972 million in 2002, predicted to increase by about 60% (1.56 billion) by 2025.(2) The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) has reported that 16% ischemic heart disease, 21% peripheral vascular diseases, and 24% acute myocardial infarction (AMI) cases are attributed to hypertension. The Population Attributable Risk due to hypertension is 29% for stroke.(3) Hypertension is responsible for 57% of all stroke deaths and 24% of all coronary heart disease deaths in India.(4)

Studies have demonstrated that multiple lifestyle changes lower blood pressure by modifying the risk factors, thereby controlling hypertension,(5–17) but the established evidences in India are inadequate. The effect of physical exercise,(6,7) salt restriction,(8) and yoga exercises(9,10) in reducing blood pressure in adults have been studied earlier, but the prevalence of hypertension among children and adolescents has increased over the past decade leading to early onset of hypertension,(18) hence we have focussed on young adults. Randomized Controlled Trials are known to be the most powerful tools in providing the strongest evidence of the efficacies of interventions. In 2007, an RCT, the first of its kind in India, undertaken in Puducherry by Saptharishi et al.,(19) to measure and compare the efficacies of the three interventions in the reduction of blood pressure among pre-hypertensive and hypertensive young adults established their efficacy.

Factors that affect blood pressure, however, are multiple and pervasive, hence difficult to quantify. Therefore, it is a challenge to attribute blood pressure reduction solely to interventions. Therefore, by eliminating the effect of the multiple influences of blood pressure like age, gender, weight, genetic influences, and observer variations, we verified the exclusive effect of the interventions by a cross-over trial of the aforementioned RCT.(19) In the process, certain limitation factors observed by Saptharishi et al.(19) like attrition rate of 9.7% and unequal-sized groups, due to early randomization of the subjects into groups prior to obtaining consent, could be eliminated, further strengthening the reliability of the results. Also, variations in the extent of each individual's response to different interventions have been speculated as proved in the case of salt restriction.(20) This issue could also be addressed by the cross-over study design.

The results of this study would motivate the community, by providing evidence of simple strategies to maintain health, and help policy makers formulate and strengthen the existing prevention strategies in bringing down the burden of hypertension.

The objectives of this study, therefore, were to measure the independent and relative efficacies of Physical Exercise, Salt Reduction, and Yoga, in lowering the blood pressure among young pre-hypertensives and hypertensives by way of a cross-over randomized controlled trial.

Materials and Methods

This study, done in Kuruchikuppam, urban service area of the Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, JIPMER, Puducherry, was a follow-up of the RCT by Saptharishi et al.,(19) and the participants who completed it formed the study population. Four out of 102 subjects could not be traced. Hence, the study began with 98 participants. The pathogenesis, risk factors, complications, therapy and benefits of prevention, and control of the disease were explained individually in the vernacular language, to motivate them for better compliance.

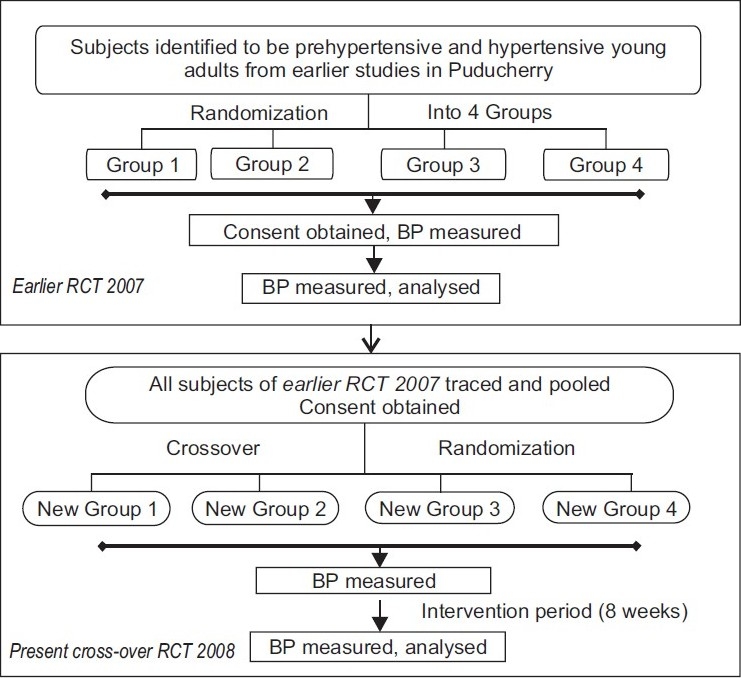

Saptharishi et al.(19) had grouped the participants into one control and three interventional groups using the standardized randomization method. In the present study, crossing over was exercised, that is, the members of each group of the earlier study were randomly allocated into any of the other three new groups, that is, a group in which they had not been in the earlier RCT(19) [Figure 1]. Therefore, at the end of this study, every participant had been a part of two different groups. This was the core step in this cross-over RCT.

Figure 1.

Methodology

The participants of the New Physical Exercise Group were motivated to perform brisk walking for 50 - 60 minutes, three to four days/week.(11,12,21) The participants of the New Salt Reduction Group reduced their daily salt intake by half.(14,15,21) They were counseled to choose foods low in salt content, like fresh fruits and vegetables, avoid foods high in salt content, like pickles, to minimize the salt used in cooking, and refrain from adding extra salt during consumption. Every fortnight, the compliance was verified through a random quantification of salt intake. Those not compliant were removed from the study. Subjects of the New Yoga Group were taught yoga exercises(22,23) effective in reducing blood pressure, by a qualified yoga instructor, and pamphlets containing the yoga lessons were distributed. They performed for 30 – 45 minutes/day, at least five days/week. It was ensured that each participant completed eight weeks of intervention, irrespective of the time they had started, and their blood pressure values measured before and after the study and compared with the New Control Group. Data analysis was done using the paired ‘t’ and ANOVA with Games-Howell post-hoc tests.

Results

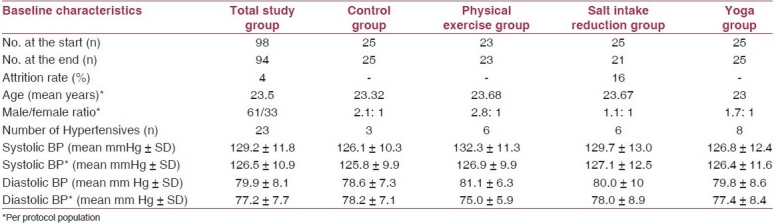

Of the 98 randomized subjects, 94 (63 males, 31 females) completed the study. Age distribution concurred in all groups, the mean age being 23 years in each group (range 21 – 25 years). The male–female distribution was similar in all groups except a slight male over-representation in the Physical Exercise group. During the course of the study four participants from the salt restriction group were excluded as they had not complied with the requirements of the intervention. The mean systolic BP in the four groups ranged between 126 and 132 mmHg and the diastolic blood pressure between 78 and 81 mmHg [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

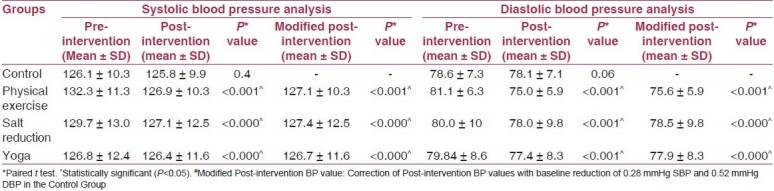

Comparison of pre, post, and modified post-intervention blood pressure values

On comparing the pre-intervention and post-intervention BP values following cross-over, using the paired ‘t’ test, the mean systolic blood pressure (SBP)/diastolic blood pressure (DBP) value in the physical exercise group was reduced by 5.4 ± 3.1/6.1 ± 2.9 mmHg, in the dietary salt restriction group the mean SBP/DBP value was reduced by 2.6 ± 1.5/2.0 ± 1.6 mmHg, in the yoga group there was reduction by 2.3 ± 1.2/2.4 ± 1.6 mmHg, and in the control group, the reduction was 0.24 ± 1.4/0.5 ± 1.4 mmHg. The mean differences in SBP and DBP in each of the three intervention groups were found to be statistically significant (P<0.05 in each case). However, the mean differences in SBP and DBP in the control group were not statistically significant [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of pre, post, and modified post-intervention blood pressure values

Hence, all three interventions showed statistically significant reduction of both SBP and DBP. Although not statistically significant, the control group recorded a reduction of 0.28 mm Hg in SBP and 0.52 mm Hg in DBP. This reduction of BP without any intervention could have been due to subjective BP variation with time or the influence of lifestyle changes in the interventional groups on the cohort of the control group. There could be a slight possibility of the influence of knowledge from the earlier study as all the control group members of this study had belonged to interventional groups in the earlier study. Assuming that the subjects of the three interventional groups would therefore have experienced a fall of at least 0.28 mm Hg SBP and 0.52 mm Hg DBP, even if they had not undergone any intervention, statistical analysis was done to eliminate this reduction of BP by subtracting 0.28 mm Hg and 0.52 mm Hg from the mean reduction of SBP and DBP (i.e., adding 0.28 mm Hg and 0.52 mm Hg to the post-intervention SBP and DBP values), respectively, in each of the intervention groups. The resultant SBP and DBP values were referred to as modified SBP and DBP, respectively. The mean difference in the reduction of both SBP and DBP when the pre-intervention values were compared with the modified post-intervention values in each of the three intervention groups, continued to be statistical significant (P<0.05 in each case), even after the adjustment for baseline reduction in the Control Group [Table 2]. Thus, the independent efficacies of the three interventions have been re-established with these results.

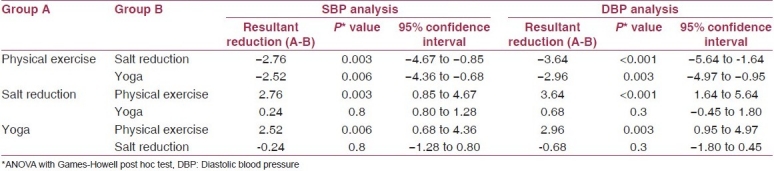

Relative efficacies of the three interventions in the reduction of blood pressure values

To compare the relative efficacies of these three interventions, the individual reductions in BP were analyzed using ANOVA with the Games-Howell post hoc test. Both per protocol and intention-to-intervene analyses were made to address the practical value/potential benefit of the intervention policy in the population and to provide unbiased comparison of the intervention groups.

In the per protocol population, that is, the 94 subjects who had successfully completed the interventions in the groups assigned to them and in the Intention-to-Intervene population of all 98 subjects, who were initially enrolled and randomized, the mean reduction in the SBP and DBP values of the physical exercise group when compared with those of the salt reduction group, was significantly higher (P<0.001). Similarly, on comparing the mean reduction in the SBP and DBP of the physical exercise group with the yoga group, the physical exercise group showed a significantly higher reduction (P<0.001). Therefore, physical exercise was inferred to be more effective than salt reduction and yoga. However, when the effectiveness of restricted salt intake and yoga on the reduction of BP were compared, there was no significant difference (P>0.05) between the two interventions. Hence, it was deduced that restricted salt intake and yoga practices were equally effective [Table 3].

Table 3.

Relative efficacies of physical exercise salt intake reduction and yoga

Discussion

Ninety-four out of 98 subjects completed this cross-over RCT, with a calculated attrition rate of 4.08%. Compared to the attrition rate of 9.7% in the earlier RCT,(19) the attrition rate in this study was brought down by more than 50% by way of randomizing the subjects into groups and by undertaking additional personal motivation via the individual/group approach. A comparative discussion follows.

Physical exercise

The present study showed 5.39 mm Hg reduction in SBP and 6.08 mm Hg in DBP in the exercise group against a reduction of 5.3 mm Hg and 6 mm Hg in SBP and DBP, respectively, in the earlier study.(19) Anand(21) through his meta-analysis showed that moderately intense exercise, for example, 30 to 45 minutes of brisk walking, four to five days a week, reduces blood pressure. In concordance, Schwarz et al.,(6) Chiriac et al.,(7) Hagberg et al.,(11) and Cleroux et al.(12) showed similar results, concurring with the results of the present study.

However, Cooper et al.,(24) concluded that the magnitude of the hypotensive effect was not as high as that found in studies of higher intensity exercise among hypertensives. Similarly Stewart et al.,(25) in his RCT on a group of hypertensives with a mean age of 63 years did not find a significant reduction in SBP, in spite of an exercise regimen spanning 78 sessions over six months. This could be due to the stiff arterial walls seen in the elderly, as it is known that arterial compliance reduces with advancing age. Church et al.(26) also did not find a significant reduction in BP post physical intervention, done over a period of six months. However, the study sample comprised of only postmenopausal obese women with a mean age of 57 years, who had a sedentary lifestyle. Park et al.(27) reported that accumulation of physical activity appeared to be more effective than a single continuous session, in the management of prehypertension.

Many published data have shown the association of physical exercise with reduction of blood pressure.(6,7,11,12,27) However, the study designs used in these studies have not addressed whether physical exercise could reduce the BP of any subjects or they had an effect only on a certain group of subjects with some specific characteristic feature.

Salt intake reduction

A reduction in the dietary salt intake as a strategy to tackle hypertension has been tried in various studies. The earlier RCT(19) showed 2.6/3.7 mm Hg reduction and the present study has shown a reduction of 2.57/2.04 mm Hg in BP. Anand(21) showed that 100 mmol/day reduction in sodium intake was associated with a decline of 5–7 mm Hg/2.7 mm Hg in hypertensive subjects. De Luis d et al.(13) recorded a 3.6 mm Hg reduction in blood pressure following reduction in dietary salt. The effects of sodium were observed by Sacks et al.(14) As compared with the control diet with a high sodium level, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet with a lower sodium level was associated with a significantly lower systolic blood pressure at each sodium level, and the difference was greater with high sodium levels than with low ones. Similarly, in the meta-analyses of longer term trials Feng et al.(8) demonstrated a consistent dose response to salt reduction. These two studies have shown a positive correlation between salt intake reduction and fall in BP.

Fodor et al.(15) found that for normotensive people a marked change in sodium intake was required to achieve a modest reduction in blood pressure. For hypertensive patients, the effects of dietary salt restriction were most pronounced if the age was greater than 44 years. Cook et al.(28) have substantiated that sodium reduction may also reduce long-term risk of cardiovascular events. All these studies have demonstrated statistically significant evidence of salt intake reduction as an intervention of hypertension, which is a key risk factor for cardiovascular diseases.

However, Hooper et al.,(29) in their meta-analysis of RCTs have determined that there are no significant long-term effects of sodium restriction in the diet and have concluded that intensive interventions provide only small reductions in blood pressure. However, this has been countered by Obarzanek et al.,(20) who stated that there could be considerable variation in the changes in BP within individuals, even when sodium, weight, and diet were constant and that this could be due to multiple reasons including measurement errors, inherent day-to-day BP fluctuation, environmental or behavioral stresses, and changes in physical activity, and hence conclusions cannot be drawn based on a single measurement or study.

Practice of yoga

The earlier RCT(19) showed significant BP reduction (2 mm Hg in SBP, 2.9 mm Hg in DBP) with only yoga as an intervention. The present study demonstrated a reduction of 2.36 mm Hg/2.44 mm Hg (SBP/DBP).

Yoga has been proven to be highly effective in reducing blood pressure by numerous Indian as well as international studies. Schwickert et al.,(9) Frumkin et al.(10) and Madanmohan et al.(22) considered yoga to be a relaxation technique that is highly effective in the reduction of elevated blood pressure and management of stress. Bijlani et al.(23) concluded that a short lifestyle modification and stress management education program with yoga as the major component led to favorable metabolic effects within nine days. Aivazyan et al.(30) demonstrated a significant reduction in SBP and DBP, peripheral vascular resistance, and hypertensive response to emotional stress, and an improvement in psychological adaptation, quality of life, and capacity for work. Singh et al.(31) reported a significant reduction in blood pressure (12 mm Hg in SBP; 11.2 mm Hg in DBP) with a 40-day yoga regimen among Type 2 diabetics.

Many studies have shown the association of each of these interventions with a reduction in blood pressure.(6–8,11,12,14,15,20,27) However, it remains to be proven whether the reduction of BP demonstrated was specifically due to the individual intervention irrespective of other influences. In the earlier RCT,(19) each intervention group showed a reduction in BP. The newly formed intervention groups in this cross-over trial also showed the same results. Therefore, this cross-over has proved the effect irrespective of other influences.

Comparison of relative efficacies

The earlier RCT(19) showed that physical exercise was more effective than the other two interventions (considered individually), whereas, both salt intake reduction and yoga were equally effective non-pharmacological interventions for the prevention and control of hypertension among young adults.

At the end of this cross-over trial, each intervention had been carried out on two different subgroups of the same study population and the analysis continued to show the same results. Hence, this cross-over RCT reaffirms the effectiveness of Physical Exercise, Salt Reduction, and Yoga, in significantly reducing blood pressure in young adults over and above the effects produced by other covariates and that Physical Exercise would be the most effective choice of intervention. Salt Reduction, and Yoga can however be advocated to the population and people who are unable to perform physical exercise, like the physically challenged, who can be advised dietary salt restriction or yoga. Maintenance of hypertension within normal limits can benefit the individual by protecting him from various cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and renal complications, as well as the Nation by bringing down the morbidity and mortality due to hypertension and consequently the burden of other related chronic non-communicable diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank ICMR, New Delhi and the participants of the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Indian Council for Medical Research

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Law MR, Elliott P, MacMahon S, Rodgers A. Blood pressure and the global burden of disease 2000.Part II: Estimates of attributable burden. J Hypertens. 2006;24:423–30. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000209973.67746.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: Analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Final report of Project WR/SE IND RPC 001 RB 02. SE/02/419575. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2004. [Last accessed on 2009 Aug 27]. WHOINDIA.org . Assessment of burden of non.communicable diseases in India. Available from: http://www.whoindia.org/LinkFiles/Assessment_of_Burden_of_NCD_Hypertension_Assessment_of_Burden_of_NCDs.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta R. Trends in hypertension epidemiology in India. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:73–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Cooper LS, Obarzanek E, Elmer PJ, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: Main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2083–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwarz S, Halle M. Blood pressure lowering through physical training-what can be achieved? MMW Fortschr Med. 2006;148:29–32. doi: 10.1007/BF03364841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiriac S, Dima-Cozma C, Georgescu T, Turcanu D, Pandele GI. The beneficial effect of physical training in hypertension. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2002;107:258–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He FJ, MacGregor GA. How far should salt intake be reduced? Hypertension. 2003;42:1093–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000102864.05174.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwickert M, Langhorst J, Paul A, Michalsen A, Dobos GJ. Stress management in the treatment of essential arterial hypertension. MMW Fortschr Med. 2006;148:40–2. doi: 10.1007/BF03364845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frumkin K, Nathan RJ, Prout MF, Cohen MC. Nonpharmacologic control of essential hypertension in man: A critical review of the experimental literature. Psychosom Med. 1978;40:294–320. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197806000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagberg JM, Park JJ, Brown MD. The role of exercise training in the treatment of hypertension: An update. Sports Med. 2000;30:193–206. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200030030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleroux J, Feldman RD, Petrella RJ. Lifestyle modifications to prevent and control hypertension.4. Recommendations on physical exercise training. Canadian Hypertension Society, Canadian Coalition for high blood pressure Prevention and Control, Laboratory Centre for Disease Control at Health Canada, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. CMAJ. 1999;160(9 Suppl):S21–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Luis D, Aller R, Zarzuelo S. Dietary salt in the era of antihypertensive drugs. Med Clin (Barc) 2006;127:673–5. doi: 10.1157/13094824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:3–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fodor JG, Whitmore B, Leenen F, Larochelle P. Lifestyle modifications to prevent and control hypertension. 5. Recommendations on dietary salt. Canadian Hypertension Society, Canadian Coalition for high blood pressure Prevention and Control, Laboratory Centre for Disease Control at Health Canada, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. CMAJ. 1999;160(9 Suppl):S29–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soudarssanane MB, Karthigeyan M, Stephen S, Sahai A. Key predictors of high blood pressure and hypertension among adolescents: A simple prescription for prevention. Indian J Community Med. 2006;31:164–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soudarssanane M, Mathanraj S, Sumanth M, Sahai A, Karthigeyan M. Tracking of blood pressure among adolescents and young adults in an urban slum in puducherry. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:107–12. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.40879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muntner P, He J, Cutler JA, Wildman RP, Whelton PK. Trends in blood pressure among children and adolescents. JAMA. 2004;291:2107–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saptharishi L, Soudarssanane M, Thiruselvakumar D, Navasakthi D, Mathanraj S, Karthigeyan M, et al. Community-based randomized controlled trial of non-pharmacological interventions in prevention and control of hypertension among young adults. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34:329–34. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.58393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obarzanek E, Proschan MA, Vollmer WM, Moore TJ, Sacks FM, Appel LJ, et al. Individual blood pressure responses to changes in salt intake: Results from the DASH-Sodium trial. Hypertension. 2003;42:459–67. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000091267.39066.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anand MP. Non-pharmacological management of essential hypertension. J Indian Med Assoc. 1999;97:220–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madanmohan, Udupa K, Bhavanani AB, Shatapathy CC, Sahai A. Modulation of cardiovascular response to exercise by yoga training. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;48:461–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bijlani RL, Vempati RP, Yadav RK, Ray RB, Gupta V, Sharma R, et al. A brief but comprehensive lifestyle education program based on yoga reduces risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:267–74. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper AR, Moore LA, McKenna J, Riddoch CJ. What is the magnitude of blood pressure response to a programme of moderate intensity exercise. Randomized controlled trail among sedentary adults with unmedicated hypertension? Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:958–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart KJ, Bacher AC, Turner KL, Fleg JL, Hees PS, Shapiro EP, et al. Effect of exercise on blood pressure in older persons: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:756–62. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.7.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Church TS, Earnest CP, Skinner JS, Blair SN. Effects of different doses of physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness among sedentary, overweight or obese postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2081–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.19.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park S, Rink LD, Wallace JP. Accumulation of physical activity leads to a greater blood pressure reduction than a single continuous session, in prehypertension. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1761–70. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000242400.37967.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook NR, Cutler JA, Obarzanek E, Buring JE, Rexrode KM, Kumanyika SK, et al. Long term effects of dietary sodium reduction on cardiovascular disease outcomes: Observational follow-up of the trials of hypertension prevention (TOHP) BMJ. 2007;334:885–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39147.604896.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hooper L, Bartlett C, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Systematic review of long term effects of advice to reduce dietary salt in adults. BMJ. 2002;325:628. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7365.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aivazyan TA, Zaitsev VP, Salenko BB, Yurenev AP, Patrusheva IF. Efficacy of relaxation techniques in hypertensive patients. Health Psychol. 1988;(7 Suppl):193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh S, Malhotra V, Singh KP, Madhu SV, Tandon OP. Role of yoga in modifying certain cardiovascular functions in type 2 diabetic patients. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:203–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]