Abstract

AIM: To compare high resolution colonoscopy (Olympus Lucera) with a megapixel high resolution system (Pentax HiLine) as an in-service evaluation.

METHODS: Polyp detection rates and measures of performance were collected for 269 colonoscopy procedures. Five colonoscopists conducted the study over a three month period, as part of the United Kingdom bowel cancer screening program.

RESULTS:There were no differences in procedure duration (χ2 P = 0.98), caecal intubation rates (χ2 P = 0.67), or depth of sedation (χ2 P = 0.64). Mild discomfort was more common in the Pentax group (χ2 P = 0.036). Adenoma detection rate was significantly higher in the Pentax group (χ2 test for trend P = 0.01). Most of the extra polyps detected were flat or sessile adenomas.

CONCLUSION: Megapixel definition colonoscopes improve adenoma detection without compromising other measures of endoscope performance. Increased polyp detection rates may improve future outcomes in bowel cancer screening programs.

Keywords: High resolution colonoscopy, Bowel cancer screening, Polyp detection

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers wor-ldwide, particularly in Europe and the United States[1]. Detection of cancer at an early stage, as well as detection and removal of polyps, is likely to decrease mortality from the disease. Colonoscopy is now established as the gold standard for the identification of both colorectal cancer and polyps[2]; therefore, the accuracy of the procedure is very important. The UK bowel cancer screening program has been established to reduce deaths from colorectal cancer utilising colonoscopy for patients screened positive by faecal occult blood tests. However, the colonoscopic miss rate of adenomas is as high as 24%[3] and the false negative colonoscopy rate for colorectal cancers appears to be up to 6%[4]. It is therefore desirable to investigate methods that could improve the accuracy of colonoscopy, particularly as a higher adenoma detection rate is associated with lower rates of subsequent development of colon cancer[5]. It has been suggested that screening efficacy requires a high quality examination and removal of all visible neoplastic lesions. It is plausible that higher image resolution will help achieve these aims[6-8]. For bowel cancer screening, we currently use Olympus Lucera colonoscopes and Scope Guide system for colorectal cancer screening. The new Pentax HiLine colonoscopes have a higher image resolution and might, therefore, provide better detection of visible polyps and early cancers. Pentax scope handling is different to Olympus scopes, and patient comfort and procedure performance may therefore be altered. This in-service evaluation of the new Pentax HiLine colonoscopes aimed to compare procedure duration, caecal intubation rates, patient comfort, and polyp detection with those obtained by the Olympus Lucera system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All patients undergoing colonoscopy in the bowel cancer screening program at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust between August and November 2009 were included in this prospective study. Routine bowel cancer screening colonoscopies are usually performed in our unit with the Olympus Lucera series of colonoscopes (CF-Q260DL colonoscopes and CLV 260-SL processor). There are five bowel cancer screening colonoscopy lists per week. During the study period, one of the screening lists was allocated to be performed with a Pentax HiLine colonoscope (EC-3890i).

A specialist bowel cancer screening nurse collected data on completeness of insertion to caecum or terminal ileum, duration of insertion, withdrawal of colonoscope, and total length of procedure in real time. In addition, the nurse noted the amount of sedation used, the level of conscious sedation (awake, drowsy, asleep), and degree of discomfort suffered by the patient during the procedure. This was classified as minimal, mild, moderate, or severe using a nurse-evaluated score in line with the National Bowel Cancer Screening standards. The location and size of polyps, as well as removal and retrieval rates, were collected. Polyps were classified by the histopathologist in charge of running the bowel cancer screening program at UCLH.

Statistical analysis was performed using non parametric Mann Whitney tests, where Gaussian approximation did not occur, and unpaired t tests where it did, for example in comparing polyp sizes. Linear regression analysis was used to assess learning curves, and χ2 contingency tests were used to compare patient parameters between scope types.

The University College London hospitals research ethics committee considered this study to be an in-service evaluation. Ethical approval was therefore not required.

RESULTS

A total of 269 procedures were recorded. Forty-four were performed with the new Pentax HiLine colonoscopes and the rest were performed with Olympus Lucera series colonoscopes. Five colonoscopists performed the procedures. An important limitation to our in-service evaluation was that most of the procedures performed with the Pentax Scopes were completed by a single colonoscopist. This colonoscopist also performed a significant number of colonoscopies with the Olympus Lucera scopes. We therefore analysed all parameters for this single endoscopist between the two scopes, as well as for all procedures preformed by all endoscopists. We found no difference between these analyses and therefore present the overall findings only. All the study colonoscopists are accredited for the UK bowel cancer screening programme and during the study, all detected adenomas in at least 40% of procedures, demonstrating their competence[5,9].

The Pentax HiLine colonoscopes were new in our unit, and these have different handling characteristics to the Olympus Lucera Scopes; therefore, we analysed the learning curve, as measured by duration of procedure and time to reach the caecum, as none of the endoscopists in this study had used this colonoscope before. There was no significant change in either of these parameters throughout the study, suggesting that there was no significant learning curve. There was no difference in caecal intubation time, duration of withdrawal, or in total procedure duration with either type of scope or between endoscopists.

No statistically significant difference was found in the caecal incubation rate, which was 100% with Olympus Scopes and 95% with the Pentax Scopes [χ2 P = 0.67, not significant (NS)]. Terminal ileal intubation was 54% with Olympus and 55% with Pentax scopes (χ2 P = 0.38, NS).

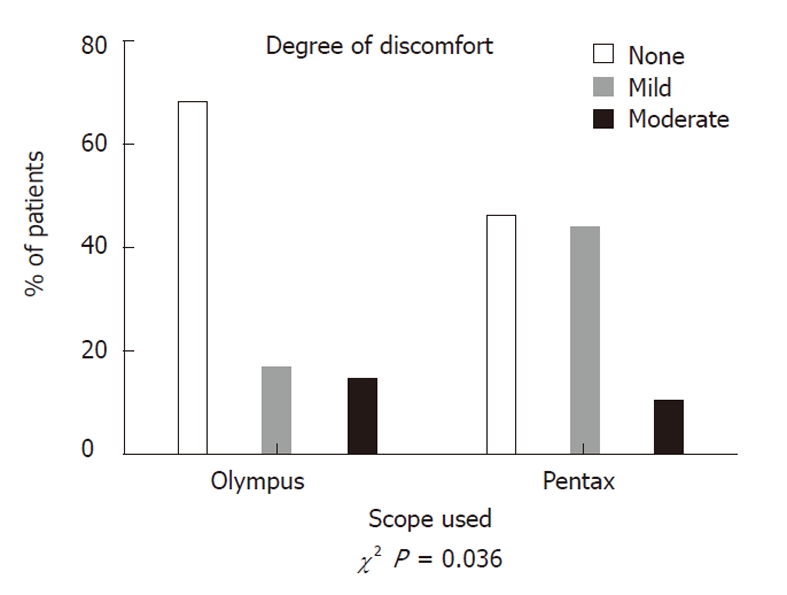

Equivalent doses of midazolam or fentanyl were used with both types of scope, with a median dose of 2 mg midazolam and 50 μg fentanyl. The depth of sedation was equivalent (χ2 P = 0.64) and the majority of patients were drowsy in both groups. More patients suffered mild discomfort with Pentax scopes (44%) compared to Olympus colonoscopies (16%), (χ2 P = 0.036). There was no increase in moderate discomfort, and no patients in either group suffered severe discomfort during the procedures (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Discomfort scores during colonoscopy. The degree of mild discomfort was worse for patients undergoing colonoscopy with Pentax scopes; however, there was no increase in moderate discomfort and no patients suffered severe discomfort with either scope.

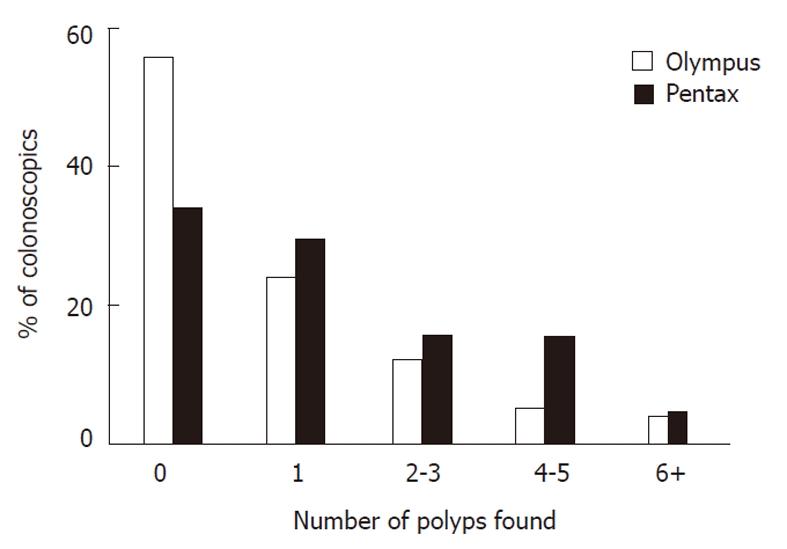

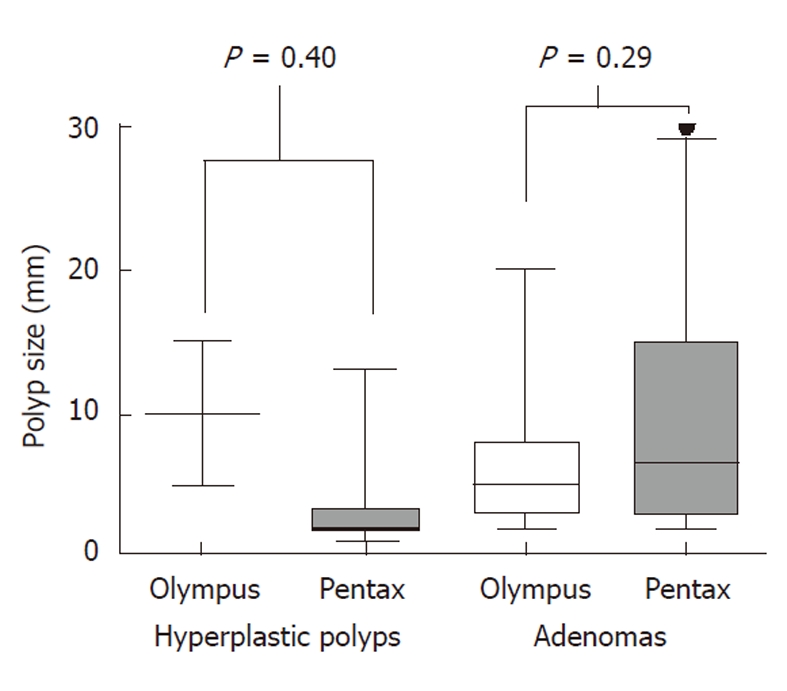

Although all colonoscopists demonstrated a high pick up rate of adenomas with both colonoscopes; a higher proportion of patients had polyps picked up when examined with the Pentax scopes (66%) compared to Olympus scopes (44%). The median number of polyps detected per procedure was also higher at one (IQR 0-3) for Pentax compared to zero (IQR 0-1) for Olympus (χ2 for trend P = 0.01) (Figure 2). The median size of polyps was identical at 4 mm in the Olympus group (IQR 2-8) and 3 mm in the Pentax group (IQR 2-8) (χ2 P = 0.98) (Figure 3). In both groups, approximately one quarter of the polyps were pedunculated and the other three quarters were sessile in nature (Fisher exact test P = 0.74. NS). More importantly, the majority of polyps found with both colonoscopes were adenomas. Although smaller polyps were more likely to be hyperplastic, there was no statistically significant difference in polyp histology whichever scope was used.

Figure 2.

Polyp detection rates. More polyps were found with Pentax HiLine colonoscopes than with Olympus Lucera colonoscopes. χ2 test for trend P = 0.01.

Figure 3.

Sizes of polyps. Box plot demonstrating that the median size of polyps was identical for both hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps for both type of colonoscope. Median, interquartile range, and minimum and maximum polyp sizes are shown for each polyp type and colonoscope.

DISCUSSION

The principal aim of the bowel cancer screening programme in the United Kingdom is to reduce the mortality from colorectal cancer by the early detection of cancerous or pre-cancerous lesions. The accuracy of colonoscopy in identifying these lesions is vital to the success of the program. Factors important in the optimisation of the test include the bowel preparation, operator skill, withdrawal time, and the image quality[5,7-11]. On the basis of prevalence of adenomas and caecal intubation rates in studies of screening colonoscopy, threshold values for rates of adenoma detection of 15% amongst women and 25% amongst men over the age of 50 have been proposed in the United States[7,12]. These have received support from a recent European Study[5]. All endoscopists taking part in the United Kingdom bowel cancer screening services must demonstrate a minimum level of competence that exceeds these thresholds.

Several studies have demonstrated the potential advantage of utilising additional optical technology, such as narrow band imaging in Olympus scopes, to improve polyp detection, although results are conflicting[13-16]. Pentax HiLine colonoscopes also have enhanced optical imaging capability, using the iScan surface and contrast enhancements[17]; however, our aims were to investigate whether white light colonoscopy with increased image resolution alone may be sufficient to improve detection, as neither narrow band imaging nor iScan enhancements are used routinely.

The quality of the final endoscopy image viewed on the screen is dependent upon all the components in the system, including the charge coupled device (CCD) chip within the scope, the processor, the cables, and the screen. CCD chips in the newer “high resolution” scopes contain more pixels, and have increased by an order of magnitude from 100 000 pixels in the older standard definition scopes to 1.3 million pixels in the latest scopes[18]. The current displays are “high definition” displaying 1080 lines, thereby further improving image quality. The Olympus Lucera colonoscope series has been available in the United Kingdom since 2003 and were the first high resolution endoscopes. The Pentax HiLine series has been marketed since 2009. The images from both video systems are viewed on a high-definition TV screen (1080 lines), but the Olympus colonoscopes have a resolution range from 400 000 to 700 000 pixels whereas the Pentax Scopes have a much higher resolution at 1.3 megapixels. It is therefore expected that the new Scopes would have a better detection rate for colonic polyps. This study has confirmed this finding, showing that there is a significantly increased chance of detecting polyps with the HiLine system compared to the Lucera system. More importantly, these polyps are significant in that they are adenomas and of a similar size to those detected with the Olympus Lucera Scopes.

The American Gastroenterological Association “Guidelines on screening and surveillance for colorectal cancer”[19] consider any adenomatous polyp, irrespective of size, to be a significant risk factor for the development of further high risk polyps or colorectal cancer. The prevalence in one large study reporting on 4967 patients identified that the majority (69%) of advanced adenomas detected were < 10 mm size. Even among polyps ≤ 5 mm, there was an appreciable prevalence of advanced adenomas (10%)[20]. Combining this with the ability to now accurately predict polyp type in vivo with the modified Kudo pit pattern and vascular colour intensity (VCI) analysis[21], enables colonoscopists to decide on which polyps to remove in vivo, irrespective of size. Consistent with this, most polyps removed in this paper were adenomas on histology.

The estimated 10-year CRC risk for unresected diminutive (< 5 mm), small (5-9 mm), and large (≥ 10 mm) polyps in a decision analysis for CT colonography (CTC) in the United States was 0.08%, 0.7%, and 15.7%, respectively; however, this analysis considered all polyps detected at CTC for these estimations. With modified Kudo pit pattern classification and VCI, accurate in vivo characterisation of polyps < 10mm can be predicted with 94% sensitivity and 89% specificity[22]. This allows non-adenomatous polyps to be resected and discarded without the need for histological assessment. Full economic modelling would be needed to assess the overall cost savings; however, the potential cost savings of not sending diminutive polyps for formal histopathology is thought to exceed 95 million dollars per year in the United States alone[23].

Rembacken and colleagues[24] have demonstrated that flat and depressed polyps are more likely to contain high grade dysplasia or invasive cancer than polypoid lesions; however, they are less easily identified and, therefore, are more likely to be missed on colonoscopy. Moreover, it is suggested that the advanced cancers appearing within three years of a negative colonoscopy may have developed from these subtle lesions[24,25]. A recent population-based study showed that 8% of colorectal cancers were missed by colonoscopy performed within the previous three years[26]. The improved overall polyp detection rate of megapixel high resolution colonoscopies demonstrated by our study, particularly for small flat adenomas could significantly improve outcomes of the bowel cancer screening program, although this hypothesis clearly needs to be formally tested in a prospective randomised controlled trial.

The Lucera colonoscopes have variable stiffness and are the standard scopes used by the majority of endoscopists in United Kingdom. The Pentax colonoscopes do not have a variable stiffness feature and feedback from individual endoscopists prior to the start of the study suggested that patients may find these scopes more uncomfortable than the Lucera Scopes. This study confirmed this finding, although the degree of added discomfort was only mild and only occurs in one quarter of patients. For the majority therefore, there was no difference in discomfort score between the two types of colonoscope. Importantly, patients did not require any more sedation. We routinely use ScopeGuide with our Lucera colonoscopes, which helps us to manage scope looping. We do not have this feature with the Pentax scopes and this might also explain the increase in mild discomfort in this group of patients.

Operators also suggested that endoscopists’ performance with the new Pentax scopes may be reduced due to changes in handling from the Olympus scopes. The performance, as measured by caecal intubation rates and procedural times, were no different between the two scopes. Moreover, no performance learning curve was detected.

Missing polyps when performing a colonoscopy is a serious problem. Several advanced imaging techniques have therefore been developed, including dye sprays, narrow band imaging, and endomicroscopy, amongst others. However, these techniques can be time consuming and require training and experience. Only techniques that are easy to perform and can be done without “high end” expertise by all appropriately trained endoscopists are suitable for screening programs. For this reason, the introduction of better image quality may be a simple solution to the problem of missed polyps at colonoscopy.

It is worth remembering that all colonoscopists who are accredited for bowel cancer screening have to demonstrate very high standards of caecal intubation and polyp detection. The fact that scope handling was no different between the scopes may not be generally applicable to all endoscopists, but it is likely to be applicable to all colonoscopists who are accredited to do bowel cancer screening, even if they are not trained to use enhanced optical detection techniques.

There are obvious limitations to this study. Although the data were collected prospectively, this is a single site study and most of the Pentax HiLine procedures were performed by a single endoscopist. All analyses, however, were carried out between the two types of endoscope for all five colonoscopists taking part in the bowel cancer screening programme, and also for the individual colonoscopists who performed procedures with both Pentax and Olympus colonoscopes. No difference was found between the two types of analysis, suggesting that the findings are robust. Nonetheless, it would be wise to confirm these findings with a multicentre, prospective, randomised controlled study involving multiple endoscopists. In addition, it would be optimal to have assessed either endoscopy system in the same patient performed by the same operator to test for a significant difference in the measured outcomes, but this would not be ethically viable. Finally, it is not certain that detecting more small polyps would actually translate to better outcomes from a national bowel cancer screening programme. It would take a very large study to prove this. Nonetheless, if the procedure takes no more time, carries minimal extra discomfort, and detects significantly more polyps, it seems reasonable to consider using this in routine practice. A prospective trial to compare the performance of these two colonoscopes for bowel cancer screening is therefore required.

COMMENTS

Background

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide, particularly in Europe and the United States, and is the 7th most common cause of death worldwide in high earning countries. To reduce the number of deaths from this disease, strategies have been designed to detect cancer at an earlier stage, and detect and remove polyps, thought to be the precursors for a large proportion of future colorectal cancers.

Research frontiers

In the United Kingdom, the national bowel cancer screening program was established to reduce deaths from colorectal cancer, utilising colonoscopy for patients screened positive with tests designed to detect minute quantities of blood in their stool. Colonoscopy was chosen as the screening modality, as it is now established as the gold standard both for the identification of colorectal cancer and polyps. The miss rate during colonoscopy, however, is unsuitably high for both the detection of significant polyps, known as adenomas (24%) and colorectal cancers (up to 6%). It is therefore desirable to investigate methods that may improve the accuracy of colonoscopy, particularly as a higher adenoma detection rate is associated with lower rates of colon cancer developing later.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Although colonoscopy is now accepted as the gold standard for the detection of colorectal cancer, a number of colonoscopes with varying technologies are now available in the market. Previous studies have compared high definition (HD) with standard video colonoscopy to show how high definition colonoscopy could detect significantly more patients with colorectal neoplasia (38 % vs 13 %), and significantly more adenomatous and cancerous polyps. Furthermore high definition endoscopy with surface enhancement could also predict the final histology with high accuracy (98.6 %) within the HD+ group. There are few studies comparing different high definition systems that have varying resolutions.

Applications

This study demonstrates that higher definition colonoscopes improve adenoma detection without compromising other measures of endoscope performance. Increased polyp detection rates may improve the outcomes of bowel cancer screening programs in the future. Future research is still needed to identify the cost effectiveness of megapixel high-resolution endoscopy systems in larger clinical studies.

Terminology

Polyps: a polyp is an abnormal growth of tissue arising from the lining of the bowel; Adenoma: an adenoma is benign tumour arising from glands inside the lining of the bowel; Histology: the microscopic study of cells and tissues.

Peer review

This article addresses the very important issue of investigating the best equipment available to endoscopist in order to adequately equip them to perform their duties to the best of their abilities. Historically, studies have concentrated on comparing groups or individuals practicing procedures. This study is unique and important as it compared two independently available endoscopy systems that are used in the United Kingdom. It demonstrates that the Pentax system is superior to the Olympus system when specifically looking at the question of polyp detection. Although the Olympus scopes are widely used and have other excellent qualities that have made them very popular in the United Kingdom, it is vital that, as endoscopists and practitioners, the authors question the quality of their equipment. This study allows bowel cancer colonoscopists to make a better and more informed decision about which endoscopy system is best for allowing them to accurately detect these pre-cancerous polyps, in their practice.

Footnotes

Supported by Proportion of UCLH/UCL funding from the Department of Health’s NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme; A grant from the UCL experimental cancer medicine centre; Unrestricted educational grant support from Pentax United Kingdom (Lovat LB)

Peer reviewer: Marc D Basson, Dr., Department of Surgery, Wayne State University and John D. Dingell VA Medical Center, 4646 John R. Street, Detroit, MI 48201, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Xiong L

References

- 1.Common cancers - UK mortality statistics. Cancer Research UK. 2010 Available from: http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/mortality/cancerdeaths/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schrock TR. Colonoscopy versus barium enema in the diagnosis of colorectal cancers and polyps. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1993;3:585–610. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rex DK, Cutler CS, Lemmel GT, Rahmani EY, Clark DW, Helper DJ, LehmanGA , Mark DG. Colonoscopic miss rates of adenomas determined by back-to-back colonoscopies. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:24–28. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bressler B, Paszat LF, Chen Z, Rothwell DM, Vinden C, Rabeneck L. Rates of new or missed colorectal cancers after colonoscopy and their risk factors: a population-based analysis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:96–102. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zwierko M, Rupinski M, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1795–1803. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pabby A, Schoen RE, Weissfeld JL, Burt MD, James W, Kikendall R, Lance P, Shike M, Lanza E, Schatzkin A. Analysis of colorectal cancer occurrence during surveillance colonoscopy in the dietary Polyp Prevention Trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02765-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, Levin TR, Burt RW, Johnson DA, Kirk LM, Litlin S, Lieberman DA, Waye JD, et al. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1296–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffman B, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Petersen BT, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:S16–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected] Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–750. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, Johanson JF, Greenlaw RL. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2533–2541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Greenlaw RL. Effect of a time-dependent colonoscopic withdrawal protocol on adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1091–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieberman D, Nadel M, Smith RA, Atkin W, Duggirala SB, Fletcher R, Glick SN, Johnson CD, Levin TR, Pope JB, et al. Standardized colonoscopy reporting and data system: report of the Quality Assurance Task Group of the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:757–766. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.East JE, Suzuki N, Stavrinidis M, Guenther T, Thomas HJ, Saunders BP. Narrow band imaging for colonoscopic surveillance in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. Gut. 2008;57:65–70. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.128926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rex DK, Helbig CC. High yields of small and flat adenomas with high-definition colonoscopes using either white light or narrow band imaging. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:42–47. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van den Broek FJ, Fockens P, Van Eeden S, Kara MA, Hardwick JC, Reitsma JB, Dekker E. Clinical evaluation of endoscopic trimodal imaging for the detection and differentiation of colonic polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rastogi A, Bansal A, Wani S, Callahan P, McGregor DH, Cherian R, Sharma P. Narrow-band imaging colonoscopy--a pilot feasibility study for the detection of polyps and correlation of surface patterns with polyp histologic diagnosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kodashima S, Fujishiro M. Novel image-enhanced endoscopy with i-scan technology. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1043–1049. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i9.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon RS, Adler DG, Chand B, Conway JD, Diehl DL, Kantsevoy SV, Mamula P, Rodriguez SA, Shah RJ, Wong Kee Song LM, et al. High-resolution and high-magnification endoscopes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winawer SJ, Zauber AJ, Fletcher RH, Stillman JS, O'Brien MJ, Levin B, Smith RA, Lieberman DA, Burt RW, Levin TR, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:143–159. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.3.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai FC, Strum WB. Prevalence of advanced adenomas in small and diminutive colon polyps using direct measurement of size. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2384–2388. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1598-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rastogi A, Pondugula K, Bansal A, Wani S, Keighley J, Sugar J, Callahan P, Sharma P. Recognition of surface mucosal and vascular patterns of colon polyps by using narrow-band imaging: interobserver and intraobserver agreement and prediction of polyp histology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:716–722. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ignjatovic A, East JR, Suzuki N, Vance M, Guenther T, Saunders BP. Optical diagnosis of small colorectal polyps at routine colonoscopy (Detect InSpect ChAracterise Resect and Discard; DISCARD trial): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler WR, Klein RW, Wielage RC, Rex DK. A quantitative assessment of the risks and cost savings of forgoing histologic examination of diminutive polyps. Endoscopy. 2011;43:683–691. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rembacken BJ, Fujii T, Cairns A, Dixon MF, Yoshida S, Chalmers DM, Axon ATR. Flat and depressed colonic neoplasms: a prospective study of 1000 colonoscopies in the UK. Lancet. 2000;355:1211–1214. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosokawa O, Shirasaki S, Kaizaki Y, Hayashi H, Douden K, Hattori M. Invasive colorectal cancer detected up to 3 years after a colonoscopy negative for cancer. Endoscopy. 2003;35:506–510. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh H, Nugent Z, Demers AA, Bernstein CN. Rate and predictors of early/missed colorectal cancers after colonoscopy in Manitoba: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2588–2596. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]