Abstract

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) has a variety of localized or systemic manifestations. Among them, Cerebrovascular dysplasia can be very rare finding of neurofibromatosis which can be very rarely seen. Here we report a case of 17-year-old boy representing bilateral giant fusiform aneurysms of extracranial internal carotid arteries and intracranial aneurysms of left middle cerebral artery. He showed no related symptoms at all, but screening for vascular lesions and close monitoring is warranted in NF-1 patients considering that it can be symptomatic unexpectedly.

Keywords: Cerebrovascular dysplasia of NF-1, Neurofibromatosis, Vasculopathy

Neurofibromatosis type 1(NF-1) is the most common neurocutaneous syndrome with multisystemic involvement of skin, nervous system, bones, endocrine glands and sometimes other organs at various sites, occurs in one of every 2,000~3,000 live births (1). It is a genetic disorder, caused by a mutation in the NF-1 gene on chromosome 17 (1). The most frequently encountered clinical findings include cafe au lait spots, freckling, neurofibromas (dermal and plexiform), optic nerve gliomas, Lisch nodules, learning disabilities and skeletal abnormalities (scoliosis and pseudoarthrosis) (2). Central nervous system manifestations of neurofibromatosis were also reported, including cranial nerve schwannomas, meningiomas, pilocytic astrocytomas, gliomas, ependymomas, angiomas and hamartomatous lesions (3). NF-1 vasculopathy is a significant but under-recognized complication of the disease. The neurovascular abnormality in NF-1 patients can be various, including intraarterial occlusive disease, arteriovenous fistula, aneurysm formation of the intracranial, extracranial carotid or vertebral arteries (4).

We report here a case of neurovascular involvement in NF-1 patient as a form of multifocal intra and extracranial aneurysms.

CASE REPORT

A 16-year-old boy had suffered from visual disturbance for about 1 year, presenting as dots and lines on the visual field of 30 minutes' duration in a month or two. He had a history of multiple surgical excision of neurofibromas from various sites by birth, and had suffered from mild right side weakness and lower extremity hemihypertrophy for a long time. He also had been afflicted with osseous abnormalities, such as anterolateral bowing of tibia, hypoplasia of fibula, diffuse enchondromatosis and osteoporosis of lower extremities which can be considered as musculoskeletal involvement of NF-1.

The physical examination revealed no definite neurologic dysfunction, except for mild right side weakness, has long been presented. The brain CT showed the porencephalic changes of the left cerebral hemisphere, which might be confused for unilateral hydrocephalus.

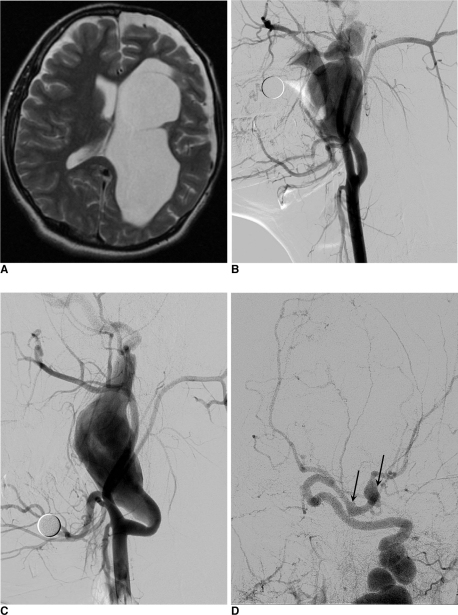

The patient was referred to our medical center for further evaluation. MR imaging demonstrated the porencephalic change of the left cerebral hemisphere with arachnoid cyst along left anterior temporal convexity (Fig. 1A). Focal ovoid shaped signal void at the inferior aspect of left temporal lobe showed continuity with M1 segment of left middle cerebral artery (MCA), suggesting focal aneurysmal dilation of left MCA. There was no infarction or other vascular malformation.

Fig. 1.

A. T2-weighted image of the patient's brain MRI shows porencephalic change of left cerebral hemisphere shows some cavitation suspiciously communicating with left lateral ventricle.

B. Angiography of the right ICA reveals large fusiform aneurysm arising from proximal ICA. The continuous draining artery shows marked tortuous dilation. The aneurysmal filling is not complete enough for the precise deliniation of whole contour of aneurysm.

C. Angiography of the left ICA reveals another giant fusiform aneurysm arising from the similar location to right side.

D. Intracranial view of left ICA angiography shows two more intracranial fusiform aneurysms (arrows) arising from proximal M1 segment and MCA bifurcation.

Conventional angiography revealed bilateral strikingly large-sized, fusiform aneurysms arising from extracranial internal carotid arteries. We also found other smaller fusiform aneurysms of proximal M1 segment and bifurcation area of left MCA. There were no abnormal findings of the vertebrobasilar arterial system (Fig. 1B, C and D).

The patient discharged without any targeted therapy for the incidentally founded aneurysms. As it was too large and extensive to apply interventional treatment and considering the fragility of aneurysmal vascular wall, the procedure would be very risky. Instead we decided to monitor the patient's status carefully.

DISCUSSION

NF-1 vasculopathy is a potentially serious but less well-known, under-recognized component of this multisystemic, genetic disorder. Recent research on the morbidity and mortality in NF-1 disclosed 2 factors independently associated with an excess of mortality in children and adults under 30 years of age, soft tissue malignancies and vascular disease (5).

Various vascular lesions of NF-1 have been noted in patients with NF-1, and are characterized by stenosis, rupture and aneurysm or fistula formation of large and medium-sized arteries. Although the arterial system is most commonly affected, venous circulation may also be involved (2). Overall, the most common manifestation of NF-1 vasculopathy is renal artery dysplasia, and hypertension is the usual manifestation. The most common form of cerebral vasculopathy in NF-1 patients is intracranial arterial occlusive disease, usually occurring in childhood or adolescence and often associated with a moya-moya pattern of collateral blood flow (4).

The precise mechanism involved in cerebral vasculopathy in NF-1 is still not well understood but are likely related to the function of neurofibromin, the protein product of the NF-1 gene (2, 5, 6). Neurofibromin has been shown to control cell growth by positively regulating intracellular level of cAMP and negatively regulating Ras signaling pathway (6). Loss of neurofibromin expression seen in NF-1 increases the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells through the RAS signaling system with subsequent intimal proliferation and arterial stenosis. It has also been shown that there is a different distribution of neurofibromin within the endothelial and smooth muscle layers in different vessels, which is thought to explain why the renal and cerebral vessels are more commonly affected than the aorta by vascular dysplasia in NF-1 (7).

The cerebral vascular lesions seen in NF-1 can be divided into three groups: stenotic lesions, aneurysmal lesion or both stenotic and aneurysmal lesion. In the reported cases, stenotic lesions occur in 71% of patients, aneurysmal lesions in 19% and both lesions in 10%. Children usually had stenotic lesions (89%), with the remaining being aneurysms only. Adults were also more likely to have stenotic lesions (39%), with aneurysm in 35% and both lesions in 26% (7). Our patient showed only aneurysmal lesions without definite stenotic lesion. Ku et al. (5) reported a case of 28-year-old woman, had bilateral giant extracranial aneurysms of the internal carotid arteries, which shows very similar manifestation of cerebral vasculopathy in NF-1 to our patient. In comparison with our case of relatively asymptomatic 17-year-old boy, the patient developed sudden-onset symptoms related to her vascular lesions followed by prompt coil embolization and graft stent placement of the affected arteries. And the aneurysms were surrounded by plexiform neurofibromas, suggesting the compression and/or infiltration by mass may have been affected the vascular wall weakening to some degree. In our case, there showed no definite relationship between neurofibromas and bilateral extracranial fusiform aneurysms. And there were other intracranial MCA aneurysms, apart from any suspected neurofibromas.

On review of the literature, the internal carotid artery was most commonly affected (44%) followed by the middle cerebral artery (19.3%), the anterior cerebral artery (16.4%) and the posterior cerebral artery (8.2%). This data shows concordance with our case, which affected both internal carotid arteries and left middle cerebral artery (7). Schievink et al. (4) reported a study suggesting that patients with NF-1 are at an increased risk of developing intracranial aneurysms. According to this article, the most common neurovascular abnormality in NF-1 patients is intracranial arterial occlusive disease, and other neurovascular manifestations of NF-1 include arteriovenous fistula and aneurysm formation of the extracranial carotid or vertebral arteries.

Although our patient was asymptomatic for his neurovascular lesions, many reports recommend detailed imaging of patients with NF-1 to clarify vascular structure and blood flow patterns and close monitoring of any neurovascular abnormalities (2,4,5,7). Because the long-term outcome of those vascular lesions has not been clearly revealed and the most vascular lesions are asymptomatic at diagnosis but can present with sudden-out symptoms. Previous reports of intracranial aneurysms in patients with NF-1 have shown that the aneurysms may be saccular or fusiform, the latter probably resulting from spontaneous arterial dissection. and screening for intracranial aneurysms generally is recommended for at-risk populations because the outcome of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is poor and treatment for most unruptured aneurysms can be accomplished safely (4).

With the knowledge of cerebrovascular dysplastic lesions as significant but under-recognized complications of patients in NF-1, the careful and detailed imaging surveillance with a low threshold for angiographic investigations is recommended independent of the presence of symptom.

References

- 1.Fortman BJ, Kuszyk BS, Urban BA, Fishman EK. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a diagnostic mimicker at CT. Radiographics. 2001;21:601–612. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.3.g01ma05601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosser TL, Vezina G, Packer RJ. Cerebrovascular abnormalities in a population of children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology. 2005;64:553–555. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150544.00016.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bognanno JR, Edwards MK, Lee TA, Dunn DW, Roos KL, Klatte EC. Cranial MR imaging in neurofibromatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151:381–388. doi: 10.2214/ajr.151.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schievink WI, Riedinger M, Maya MM. Frequency of incidental intracranial aneurysms in neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;134A:45–48. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ku YK, Chen HW, Fu CJ, Chin SC, Liu YC. Giant extracranial aneurysms of both internal carotid arteries with aberrant jugular veins in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1750–1752. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Listernick R, Ferner RE, Liu GT, Gutmann DH. Optic pathway gliomas in neurofibromatosis-1: controversies and recommendations. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:189–198. doi: 10.1002/ana.21107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cairns AG, North KN. Cerebrovascular dysplasia in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:1165–1170. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.136457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]