Abstract

Introduction

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor is a rare malignancy with poor prognosis that predominantly affects young males. Its etiopathogenesis is still unknown and diagnosis can be achieved only by immunohistochemistry and cytogenetic studies. Due to our limited knowledge of the pathologic and clinical nature of this disease, there is no clear consensus regarding the optimal therapeutic procedures for treating this neoplasm. A high degree of care and improvements in diagnostic capabilities are required in order to identify this entity and avoid misdiagnosis.

Case presentation

We report a new case of a 29-year-old male who proceeded to our Emergency Department complaining about non-specific abdominal pain. Physical examination revealed no abnormalities except for a palpable mass in the lower abdomen and a diffuse abdominal pain. Computed Tomography scan showed enlarged paraortic and mesenteric lymphadenopathy, thickness of the small bowel wall and dispersed masses intraperitoneally. He underwent an exploratory laparotomy and the resultant biopsy revealed desmoplastic small round cell tumor.

Discussion

Diagnosis of desmoplastic small round cell tumor can easily be missed because it presents with few early warning symptoms and signs, while the routine blood tests are within normal limits.

Conclusion

A high degree of suspicion, a thorough physical examination, a full imaging check and an aggressive therapeutic approach are required in order to identify this disease and fight for a better quality of life for these patients. In addition we make a review of the literature in an effort to clarify the epidemiological, clinical and pathological aspects of this entity.

Keywords: Intraabdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor, Peritoneal tumor, Surgery, Pathology

1. Introduction

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is a highly aggressive and extremely rare malignant neoplasm with poor prognosis that was first described by Sesterhenn et al. only two decades ago.1 It is considered a childhood cancer that predominantly strikes male adolescents and young adults. This neoplasm primarily occurs as multiple, widespread masses in the abdomen and pelvis without an apparent organ of origin and may be accompanied by extensive tumor implants throughout the peritoneum.2,3 It is characterized by nests of small undifferentiated cells that show immunohistochemical evidence of epithelial, mesenchymal and neural differentiation. DSRCTs present a reciprocal chromosomal translocation, t(11;22)(p13;q11 or q12), that results in the expression of a Ewing's sarcoma and Wilm's tumor-1 fusion gene with chimeric message.4

Due to our limited knowledge on the pathologic and clinical nature of this disease, there is no clear consensus regarding the optimal therapeutic procedures for treating this neoplasm. Moreover, a high degree of care is required by the clinical physicians and improvements in diagnostic capabilities in order to identify this entity and avoid misdiagnosis. We herein describe a new case of this rare disease; a young male who visited our hospital's Emergency Department complaining about vague abdominal symptoms.

2. Case presentation

2.1. Clinical history

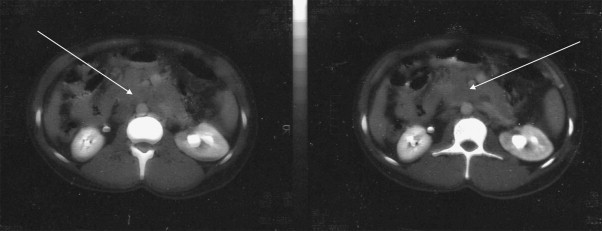

A 29-year-old male from the Middle East living in Greece for the last two years presented to our hospital's Emergency Department complaining about non-specific abdominal pain. He had been in good health until two months before, when he started feeling exhausted, having anorexia, nausea, abdominal distension and pain. Physical examination revealed no abnormalities except for a palpable mass in the lower abdomen and a diffuse abdominal pain. The hemogram and the serum biochemistry were within normal limits. The inflammation markers (CRP, ferritin, fibrinogen, ESR) and tumor markers (βHCG, AFP, CEA, CA 19.9)5 were normal, too. The tumor marker CA 125 was the only marker that was elevated by 5 times above the normal range. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed enlargement of the right kidney, splenomegaly and free fluid in the upper compartment of the abdomen. Computerized Tomography (CT) scan showed enlarged paraortic and mesenteric lymphadenopathy (block), thickness of the small bowel wall and dispersed masses intraperitoneally (Fig. 1). The preoperative diagnosis was lymphoma or tuberculosis of the small bowel. He underwent an exploratory laparotomy and the resultant biopsy revealed DSRCT.

Fig. 1.

CT image of a large intraabdominal DSRCT: enlarged paraortic and mesenteric lymphadenopathy and dispersed masses intraperitoneally.

During the post-operative period he presented recurrent ascites, hypertension and mild post-operative pancreatitis (with increased serum and urine amylase). CT scan of the pancreas and adrenal glands as well as the serum cortisol and aldosterone levels were within normal range. The tumor marker CA 125 returned to normal on the fifth postoperative day. He underwent conservative treatment with improvement of his general condition.

When he was stabilized he was referred to the Oncology Department of St. Savvas Hospital. He underwent chemo-radiation therapy according to the P6 protocol. The latter consists of 7 courses involving cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, ifosfamide and itoposide.2,6,7 Unfortunately, our patient received only three cycles of chemotherapy because he decided to leave for his country. Therefore he was lost to the follow-up and ever since all trace of him has been lost. He was also planned to receive whole abdominal radiotherapy (30 Gy). Radiation treatment started when he had already undergone three cycles of chemotherapy but only one fraction was given up to the time he decided to leave. Up to that time all courses of treatment were well-tolerated and he was in good general condition.

2.2. Surgical treatment

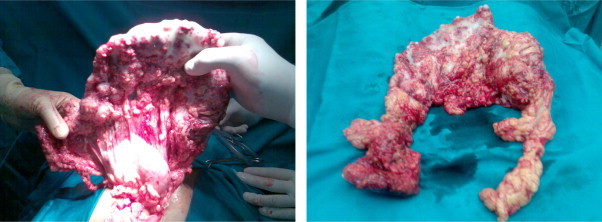

The exploratory laparotomy revealed ascites and an infiltration of the whole great omentum from a malignant tumor, as well as many secondary deposits to the abdominal wall and to the bowel. The great omentum was resected (Fig. 2) and biopsies were taken from all over the abdominal cavity.

Fig. 2.

The great omentum that was resected.

2.3. Pathological findings

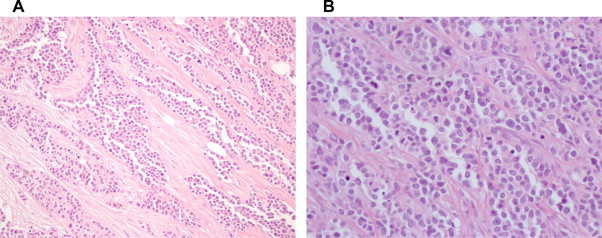

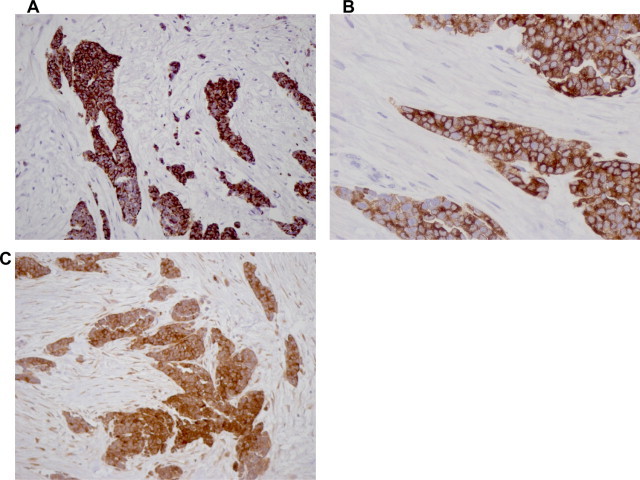

Our pathology department received the great omentum. It measured 23 × 17 × 5.5 cm in size and had white or grey-white areas of a hard-elastic consistency with a diameter of 2–7.5 cm. Microscopically, these white or grey-white areas were composed of sharply demarcated nests of varying size with small round or oval cells, embedded in a desmoplastic stroma. Some tumor cells had small hyperchromatic nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli. In some areas the tumor cells formed cords surrounded by desmoplastic stroma (Fig. 3). The immunohistochemical study included: ABPAS, ABPAS D, vimentin, smooth muscle actin (SMA), desmin, S-100 protein, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), antimelanotic antigen (HMB45), platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD31), human hematopoietic progenitor cell antigen (CD34), Leu M1 (CD15), synaptophysin, chromogranin, Leu-7 (CD57), MIC2 (CD99), Leucocyte common antigen (LCA), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cytokeratins (CK7, CK19, CK20, CAM 5.2, a1-fetoprotein, P53, Ki 67, c-kit).8–11 The immunohistochemical results revealed positive to: vimentin, desmin, NSE, CD15 (in a few cells), CD57, MIC2, EMA, CK7, CAM 5.2, a1AFP, P53 (in a few cells), Ki 67 (increased activity). (Fig. 4) The histological findings were consistent with DSRCT.

Fig. 3.

Histological spectrum of DSRCT. (a) HE 20× desmoplastic stroma, medium size round cells, scant cytoplasm and indistinct borders, (b) HE 40× inconspicuous nucleoli.

Fig. 4.

Immunoprofile of DSRCT. (a) DESMIN 20× strong cytoplasmic staining, (b) NSE 20× strong immunoreactivity, (c) EMA 40× EMA diffuse membrane immunoreactivity.

3. Discussion

DSRCT is a rare neoplasm, firstly recognized in 1987 by Sesterhenn et al. who described 17 cases of young males with undifferentiated malignant epithelial tumor arising in the pelvis or scrotum.1,6,12 Ever since only case reports or small series of patients have been announced, making diagnosis and management of this disease a challenge for the physicians.

DSRCT shares characteristics with other small round cell malignancies including Ewing's Sarcoma, small cell Mesothelioma, Neuroblastoma, Lymphoma, Primitive Neuroectodermal tumor, Rhabdomyosarcoma and Wilm's tumor. That is why the DSRCT was until recently classified as a soft tissue undifferentiated sarcoma.6,7,10,13 Pathology reveals clusters of small to medium sized cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and increased nuclear/cytoplasm ratio, surrounded by a dense desmoplastic stroma.6 Immunohistochemical findings suggest a trilinear coexpression including the epithelial marker keratin, the mesenchymal markers desmin and vimentin, and occasionally the neuronal marker neuron-specific enolase (Primitive neuroectodermal tumors/Ewing Sarcoma – PNET/ES – are desmin negative, neuroblastoma is vimentin and desmin negative, small cell mesothelioma is desmin, CD15, CD57 negative).8–11 Recent studies have shown that DSRCTs present a reciprocal chromosomal translocation, t(11;22)(p13;q11 or q12) that results in fusion of exon 7 of the Ewing's sarcoma gene EWS on chromosome 22 with exon 8 of the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene WT1 on chromosome 11. The EWS/WTI transcript is diagnostic of this tumor and codes for a protein that acts as a transcriptional activator that fails to suppress tumor growth.4,13,14

This extremely rare tumor chiefly affects males (96%) in their second or third decade of life. It behaves aggressively and only 29% of patients survive up to 3 years.12 No ethnic predisposition or other known risk factors have been identified specific for the disease. The neoplasm usually appears as an extensive intraabdominal or less often endopelvic mass with widespread peritoneal and lymphatic dissemination, without an apparent organ of origin. Other areas less often affected may include lymph nodes, the lining of the abdomen, diaphragm, spleen, liver, lungs, testicles and ovaries. The most common sites of metastatic spread are the liver, lungs and bones.

Despite the enormous size the tumors can grow to, there are few early warning signs. The majority of patients are young and healthy as the tumor grows and spreads uninhibited within the abdomen or pelvis. The most common presenting symptoms and signs of intraabdominal DSRCT include abdominal pain, distension, lack of appetite, a palpable abdominal mass, which are nonspecific and nondiagnostic.7 The most common and useful imaging tool is the CT scan with intravenous and per os contrast. Although the CT scan is not diagnostic, the pattern of tumor distribution can be very suspicious for DSRCT. Bulky, heterogeneous peritoneal soft tissue masses without an apparent organ-based primary and mesenteric lymphadenopathy are characteristics of DSRCT. Diagnosis can only be made after removal of the suspicious mass and histological analysis with immunohistochemical demonstration of the trilinear nature of the tumor.7,12 Fine needle aspiration cytology has also been used for the diagnosis but still it's not the most preferable way, since molecular cytogenetics require larger biopsies.2,12

The ideal therapeutic strategy for treating this neoplasm is still unclear due to the rarity of the tumor and consequently the limited experience. Most reports suggest total resection of the mass and postoperative multiagent chemotherapy and radiation therapy as the best therapeutic options. Total resection is not often feasible because of the numerous peritoneal implants. Some authors suggest preoperative chemotherapy as a way of shrinking the widespread mass and reducing its vascularity. Intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemoperfusion has also been administered as an effort to reduce the bulk of the tumor. The experience with pseudomyxoma peritonei is behind this concept. Despite the combined therapeutic approach, including surgery and chemoradiation therapy, the prognosis for these patients remains very poor, especially for those with metastatic disease – 29% for a 3-year survival and just 18% for a 5-year survival.12,15

4. Conclusion

A high degree of suspicion, a thorough physical examination, a full imaging check and an aggressive therapeutic approach are required in order to identify this disease and fight for a better quality of life for these young patients. The tumor marker CA 125 might be a marker for the follow up of these patients, if it is elevated at baseline. Future genetic therapies focused on developing targeted immunotherapy, might promise more optimistic results. Until then more than one medical specialities should collaborate in order to face the challenge and treat such patients.

Conflict of interest statement

No competing financial interest exists.

Funding

None.

Authors’ contributions

K.K. examined the patient at the Emergency Department, treated him while he was hospitalized and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. H.M. performed the histological examination of the great omentum and was a contributor in writing the manuscript. M.N. assisted the surgeon to perform the operation and was a contributor in writing the manuscript. O.C. assisted the pathologist to perform the histological examination of the great omentum. O.G. examined the patient at the Emergency Department and treated him while he was hospitalized. V.M. treated the patient while he was hospitalized. G.K. performed the operation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Katerina Koniari, Email: ekoniari@med.uoa.gr.

Marinos Nikolaou, Email: nikolaoumarinos@yahoo.gr.

Vasilios Magiasis, Email: magiasiskat@yahoo.com.

Georgios Kiratzis, Email: costas1907@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Sesterhenn I., Davis C.J., Mostofi F.K. Undifferentiated malignant epithelial tumors involving serosal surfaces of escrotum and abdomen in young males. J Urol. 1987;137:214A. [Google Scholar]

- 2.La Quaglia M.P., Brennan M.F. The clinical approach to desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Surg Oncol. 2000;9:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(00)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerald W.L., Rosai J., Ladanyi M. Characterization of the genomic breakpoint and chimeric transcript in the EWS-WT1 gene fusion of desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(4):1028–1032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawyer J.R., Tryka A.F., Lewis J.M. A novel reciprocal chromosome translocation t(11;22)(p13;q12) in an intraabdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:411–416. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199204000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Gonzalez J., Villanuena C., Fernadez-Acenero J., Paniagua P. Paratesticular desmoplastic small round cell tumor: case report. Urol Oncol: Sem Orig Invest. 2005;23:132–134. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amato R.J., Ellerhorst J.A., Ayala A.G. Intraabdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor: report and discussion of five cases. Cancer. 1996;78(4):845–851. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960815)78:4<845::AID-CNCR22>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassan I., Syyan R., Donohue J.H., Edmonson J.H., Gunderson L.L., Moir C.R. Intraabdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Cancer. 2005;104(6):12641270. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerald W.L., Rosai J. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor with multi-phenotypic differentiation. Zentralbl Pathol. 1993;139:141–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerald W.L., Rosai J. Case 2. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor with divergent differentiation. Pediatr Pathol. 1989;9:177–183. doi: 10.3109/15513818909022347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnoud R., Sabourin J.C., Pasquier D., Ranchere D., Bailly C., Terrier-Lacombe M.J. Immunohistochemical expression of WT1 by desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a comparative study with other small round cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:830–836. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200006000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill D.A., Pfeifer J.D., Marley E.F., Dehner L.P., Humphrey P.A., Zhu X. WT1 staining reliably differentiates desmoplastic small round cell tumor from Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor. An immunohistochemical and molecular diagnostic study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114:345–353. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/114.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mingo L., Seguel F., Rollan V. Intraabdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:279–281. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerald W.L., Ladanyi M., de Alava E., Cuatrecasas M., Kushner B.H., LaQuaglia M.P. Clinical, pathologic and molecular spectrum of tumors associated with t(11;22)(p13;q12): desmoplastic small round-cell tumor and its variants. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3028–3036. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biegel J.A., Conard K., Brooks J.J. Translocation (11;22)(p13;q12): primary change in intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1993;7:119–121. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870070210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kushner B.H., La Quaglia M.P., Wollner N. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: prolonged progression-free survival with aggressive multimodality therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1526–1531. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]