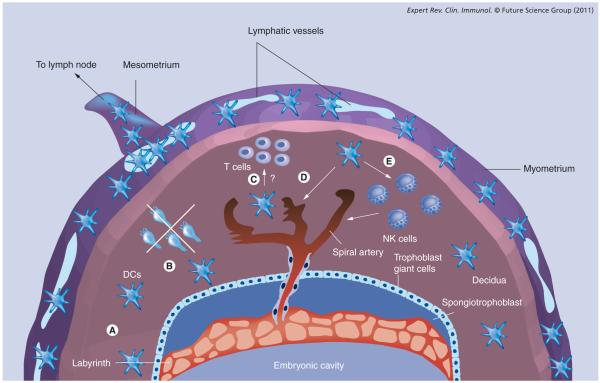

Figure 1. Dendritic cell function at the maternal–fetal interface.

A schematized representation of the pregnant mouse uterus, illustrating the various dimensions of decidual DC function discussed in the text (A–E). Two complementary mechanisms minimize the exposure of fetal/placental alloantigens to T cells: (A) the progressive decline of decidual DC tissue densities over the first half of the postimplantation period; and (B) the inability of the few remaining DCs to migrate to the regional lymph nodes. Decidual entrapment is in turn linked to the lack of lymphatic vessels in the mouse decidua, a feature apparently shared with the human uterus. In mice, uterine lymphatic vessels are confined to the myometrium, at a distance of up to 1 mm away from the surface of the placenta. (C) Interactions between decidual DCs and T cells. In humans, these interactions have been suggested by the clustering of T cells around decidual DCs, but their functional significance is unknown. (D & E) Trophic functions of uterine DCs in decidual vascularization. These functions might include direct effects on decidual vessel maturation (D), or indirect effects, via uterine NK cells, on vascular remodeling. In addition, uterine DCs are thought to be important for initializing the decidual reaction induced by embryo implantation (not depicted).

DC: Dendritic cell; NK: Natural killer.