Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess the reasons for discontinuing or continuing olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia, from the perspectives of the patients and their clinicians.

Methods

The Reasons for Antipsychotic Discontinuation/Continuation (RAD) is a pair of questionnaires assessing these reasons from the perspectives of patients and their clinicians. Outpatients with schizophrenia (n = 199) who were not acutely ill participated in a 22-week open-label study of olanzapine from November 2006 to September 2008. Reasons for continuing or discontinuing olanzapine (on a five-point scale), along with the single most important reason and the top primary reasons, were identified. Concordance between reasons given by patients and clinicians was assessed.

Results

The top primary reasons for continuing olanzapine were patients’ perceptions of improvement, improvement of positive symptoms, and improved functioning. The study discontinuation rate was low (30.2%), and only a subset of patients who discontinued reported reasons for medication discontinuation. The top primary reasons for discontinuing olanzapine were insufficient improvement or worsening of positive symptoms, adverse events, and insufficient improvement or worsening of negative symptoms. Ratings given by patients and clinicians were highly concordant.

Conclusion

The main reason for continuing or discontinuing olanzapine appears to be medication efficacy, especially for positive symptoms. Reasons for medication discontinuation differ somewhat from reasons for continuation, with a high level of concordance between patient and clinician responses.

Keywords: antipsychotic agents, schizophrenia, olanzapine, questionnaires

Introduction

Treatment discontinuation for any cause is considered a proxy measure of effectiveness of a medication (or lack thereof), reflecting its efficacy, safety, and tolerability.1 Prior studies1 have assessed reasons for discontinuation of medication using only a few categories (eg, patient decision, lack of efficacy, or medication intolerability). These responses do not identify the specific reasons for medication discontinuation from a patient perspective, clinician perspective, or both, and require respondents to choose only one reason when more than one may apply. Furthermore, reasons for continuing a medication have seldom been collected. In response to sparse data regarding patient discontinuation or continuation of medications, two measures were developed to assess the specific Reasons for Antipsychotic Discontinuation/Continuation (RAD), one from the clinician perspective2 and one from the patient perspective.3

In a previous 12-week study4 of markedly ill schizophrenia patients experiencing acute psychotic exacerbations, improvement of positive symptoms was found to be the single most important reason for continuation of medication, and lack of improvement or worsening of positive symptoms was the most important reason for discontinuation of medication, from the perspectives of both patient and clinician. However, it is unclear if these findings were an artifact of patient selection criteria, because improvements in positive symptoms are expected to be highly valued by markedly ill patients with acute psychotic exacerbations and their treating physicians.

The present study aimed to assess whether the prior findings could be replicated when using data on reasons for continuing or discontinuing olanzapine among moderately ill outpatients with schizophrenia, who were not required to be acutely ill or to have prominent positive symptoms to be enrolled in the study. The primary objective was to assess prospectively the specific reasons for continuing or discontinuing olanzapine therapy in outpatients with schizophrenia, from both patient and clinician perspectives.

Materials and methods

Data on reasons for continuing or discontinuing olanzapine therapy were collected during a multicenter, randomized, open-label, 22-week international trial that enrolled 199 outpatients with schizophrenia from November 2006 to September 2008. The study was designed to determine if weight gain during olanzapine treatment can be prevented or mitigated using an algorithm including adjunctive medication with amantadine, metformin, or zonisamide. Patients were randomized 3:1 to receive either olanzapine in combination with an adjunctive medication algorithm plus behavioral instruction (n = 149) or olanzapine alone plus behavioral instruction (n = 50). Patients randomized to treatment with the adjunctive medication were randomized again, 1:1, to a pharmacological algorithm beginning with amantadine (n = 76) or an algorithm beginning with metformin (n = 73). Details about the parent study are available elsewhere.5

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients after they received a complete description of the study. All procedures were approved by institutional review boards for all study sites and were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients included men and women aged 18–65 years with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (295.XX from DSM-IV-TR [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision]) having a body mass index of 20–35 kg/m2, with a maximum of 25% of patients at <23 kg/m2 or >30 kg/m2. Investigators determined that each patient required a change in current antipsychotic treatment and that olanzapine was a reasonable choice. Patients requiring treatment with mood stabilizers or antidepressants had to be stabilized on these medications with no changes in therapy in the 30 days prior to the screening visit and no changes during the study. Patients were excluded if, in the opinion of the investigator, they were resistant to treatment with olanzapine; had a substance dependence diagnosis (other than nicotine or caffeine) within 30 days prior to the screening visit; had a plasma prolactin concentration >200 ng/mL at the screening visit; had a history of eating disorders (307.XX); or was on current treatment with amantadine, metformin, or zonisamide. Patients diagnosed with diabetes or receiving treatment or nutrition therapy for diabetes were also excluded.

Measures

RAD

Two measures previously developed to assess RAD were recently validated using clinical trial data.6 One is a semi-structured interview conducted by trained interviewers to assess patient reasons for discontinuing or continuing their antipsychotic medications (RAD-I).3 Data were collected by having interviewers complete the measure and choose the appropriate options based upon information they collected during the patient interviews. The second measure is a questionnaire assessing patient reasons for discontinuing or continuing their medications from the clinician perspective (RAD-Q).2

The RAD-I and RAD-Q include 25 items assessing reasons for discontinuation of medication and 21 (RAD-I) or 18 (RAD-Q) items assessing reasons for continuation of medication. The items were selected based on a comprehensive literature review, a patient interview pilot study, and input from an expert working group. Patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and their clinicians completed the draft measures and structured cognitive debriefing interviews assessing the comprehensibility, clarity, and comprehensiveness of the measure. The draft measures were further revised following cognitive debriefing interviews with clinicians, patients, and interviewers. A detailed description of the development of the RAD measures can be found elsewhere.7

In the present study, these measures were assessed at baseline to identify reasons for discontinuing medication used prior to the study start, at endpoint (22 weeks) to assess the reasons for continuing olanzapine therapy, and at discontinuation (if the patient discontinued olanzapine prior to study completion) to identify the reasons for discontinuing treatment with olanzapine. Selected items of the RAD instruments are presented in Table 1. Each reason was rated as a primary reason, a very important reason, a somewhat important reason, a minor reason, or not a reason. After the reasons were identified and rated, the single most important reason was also identified. Patients were interviewed to collect their responses on the RAD, and interpretations were derived from the RAD data and not from statements made during the interview.

Table 1.

Select items from the reasons for antipsychotic discontinuation/continuation

Reasons for discontinuation

|

Statistical methodology

Statistical analyses were completed for the reasons patients discontinued the medication used prior to the study, the reasons for discontinuing olanzapine (if discontinued), and the reasons for continuing olanzapine (if the study was completed). Descriptive statistics were used to assess the frequency with which patients (RAD-I) and clinicians (RAD-Q) identified each of the reasons as the single most important reason and/or a primary reason(s). Analysis combined “symptoms not sufficiently improved” and “symptoms made worse” into a single item, ie, “symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse.” Paired t-tests were used to compare the mean number of any reasons reported by patients versus those reported by clinicians. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to assess concordance between the group rankings of all the patient reasons and the group rankings of all the clinician reasons (for the single most important reason and again for the primary reason). Fisher’s Exact test was used to assess the association between discontinuing the prior drug due to positive symptoms as a primary reason and continuing olanzapine due to positive symptoms as a primary reason.

Results

The RAD measures were administered to 199 outpatients at study entry, and data were available for 191 patients. Their baseline characteristics are presented in Table 2, showing that, on average, patients were in their late 30s, mostly male, about 44% Caucasian, and about 26% Hispanic. They had a mean Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S) score of 4.0.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of 191 study patients with Reasons for Antipsychotic Discontinuation/Continuation (RAD-I [patient]) or RAD-Q [clinician]) data

| Age (years, mean, SD) | 38.6 (±12.0) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 76 (39.8%) |

| Male | 115 (60.2%) |

| Ethnicity/race | |

| Caucasian (n, %) | 84 (44.0%) |

| African descent (n, %) | 14 (7.3%) |

| East Asian (n, %) | 38 (19.9%) |

| Hispanic (n, %) | 50 (26.2%) |

| Native American (n, %) | 1 (0.5%) |

| West Asian | 4 (2.1%) |

| MADRS total (mean, SD) | 14.3 (9.8) |

| BPRS total score (mean, SD) | 47.0 (14.2) |

| BPRS positive score (mean, SD) | 12.3 (5.5) |

| CGI-S (mean, SD) | 4.0 (1.1) |

| EQ-5D (mean, SD) | |

| US Population-Based Index score | 0.7 (0.2) |

| Visual Analog Scale Health State score | 62.1 (24.3) |

| Weight (kg, mean, SD) | 77.6 (16.7) |

| Body mass index (mean, SD) | 27.1 (4.7) |

Abbreviations: BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression-Severity; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; SD, standard deviation.

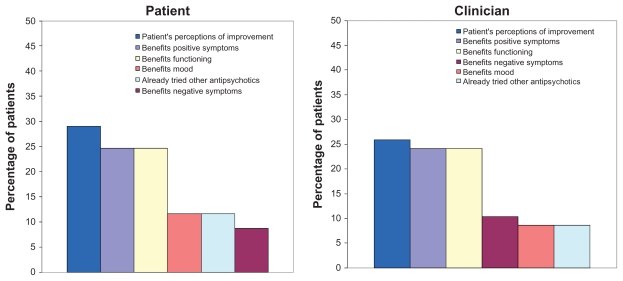

Reasons for continuing olanzapine

Study completion rate was relatively high (70%). Of the 139 patients who completed the study, about half of the patients (n = 69, 49.6%) and their clinicians (n = 58, 41.7%) reported reasons for continuing olanzapine. Of 139 patients who finished the study, 70 (50.4%) had data from the Reasons for Medication Continuation measure. Among patients continuing on olanzapine, those who had data from this measure did not differ significantly on baseline characteristics from those who did not have data from this measure. The mean numbers of reasons for continuing olanzapine given by patients and clinicians were 8.5 (standard deviation [SD] = 4.0) and 7.3 (SD = 2.6), respectively (P = 0.009). From the patient perspective, the reasons given as the single most important reason for continuing olanzapine were “benefits functioning” (25.0%), “patient’s perceptions of improvement” (23.3%), and “benefits positive symptoms” (13.3%). From the clinician perspective, the most frequently identified reasons were “benefits positive symptoms” (24.5%), “patient’s perceptions of improvement” (22.6%), and “benefits functioning” (20.8%). For patients and clinicians, the top primary reasons for continuing olanzapine were “patient’s perceptions of improvement” (29.0% and 25.9%), “benefits positive symptoms” (24.6% and 24.1%), and “benefits functioning” (24.6% and 24.1%, respectively, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Primary reasons for continuing on olanzapine (n = 69 patients; n = 58 clinicians).

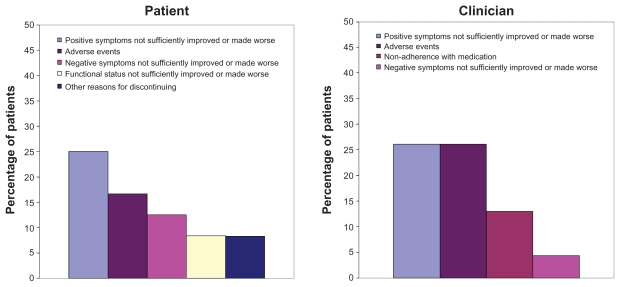

Reasons for discontinuing olanzapine

A total of 60 patients (30.2%) discontinued the study. Fewer than half of these patients (n = 24, 40%) and their clinicians (n = 23, 38.3%) reported reasons for discontinuing olanzapine. Among patients discontinuing olanzapine, those who did not respond to the Reasons for Medication Discontinuation measure were significantly more likely to be African-American or Hispanic, and had more depressive symptoms, greater illness severity, and poorer quality of life than patients who discontinued the study and responded to this measure.

The mean number of reasons for discontinuing olanzapine from the patient perspective was 2.3 (SD = 2.9) and 3.7 (SD = 5.4) from the clinician perspective. These means were not significantly different (P = 0.223). From the patient perspective, the reasons given as the single most important reason for discontinuing olanzapine were “adverse events” (28.6%) and “mood not sufficiently improved or made worse” (19.0%). From the clinician perspective, the reasons given were “adverse events” (30.0%), “nonadherence with medication” (25.0%), and “positive symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” (20.0%).

The top primary reasons for discontinuing olanzapine from the patient perspective were “positive symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” (25.0%), “adverse events” (16.7%), and “negative symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” (12.5%, Figure 2). The adverse events were vomiting, hyperglycemia, insomnia, nausea, and oversleep, each reported by one patient. The top primary reasons from the clinician perspective were “positive symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” (26.1%), “adverse events” (26.1%), and “nonadherence with medication” (13.0%). The adverse events included tingling sensation in legs, dizziness, hyperglycemia, somnolence, and insomnia, each recorded by one clinician.

Figure 2.

Primary reasons for discontinuing olanzapine (discontinuation after visit 2; n = 24 patients; n = 23 clinicians).

Reasons for discontinuing drug used prior to study start

Prior to the study start, 24.9% of patients were treated with oral risperidone, 24.3% with typical antipsychotic drugs, 30.5% with “other drugs” (primarily quetiapine and aripiprazole), and there was no information for 20.3%. Of the 199 patients, 177 (88.9%) had RAD data for discontinuing the drug used prior to study start. The mean numbers of reasons given by patients and clinicians were 4.1 (SD = 3.2) and 4.6 (SD = 3.1), respectively (P = 0.008). From the patient perspective, the reasons given as the single most important reason for discontinuing the drug used prior to study start were “positive symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” (26.2%), “patient wishes to try a new antipsychotic” (21.6%), and “adverse events” (19.0%). The most common adverse events were akathisia and tremors. From the clinician perspective, the reasons given were “positive symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” (32.4%), “adverse events” (20.3%), and “patient wishes to try a new antipsychotic” (12.8%). The adverse events reported most frequently were extrapyramidal symptoms and weight gain.

For patients, the top primary reasons for discontinuing prior drugs were “positive symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” (15.3%), “patient wishes to try a new antipsychotic” (11.8%), and “adverse events”/“functional status not sufficiently improved or made worse” (both 10.6%, Figure 3). For clinicians, the reasons were “positive symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” (20.2%), “negative symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” (11.6%), and “functional status not sufficiently improved or made worse” (11.0%).

Figure 3.

Primary reasons for discontinuing the drug used prior to study start (n = 170 patients; n = 173 clinicians).

Concordance between patients’ and clinicians’ ratings

For the single most important reason, there were statistically significant correlations between patient and clinician reasons for continuing olanzapine (rs = 0.96; P < 0.0001), discontinuing olanzapine (rs = 0.58; P = 0.003), and discontinuing the medication used prior to study start (rs = 0.91; P < 0.0001). Statistically significant correlations were also found for the primary reasons for continuing olanzapine (rs = 0.96; P < 0.0001), discontinuing olanzapine (rs = 0.64; P = 0.001), and discontinuing the medication used prior to study start (rs = 0.92; P < 0.0001).

Patient continuation on olanzapine and discontinuation of prior drugs

Of the 70 patients who had either RAD-I or RAD-Q continuation measures, 10 discontinued prior drugs due to “positive symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” as a primary reason and 60% of those patients (six of ten) continued olanzapine due to “benefits for positive symptoms” as a primary reason. For the other 60 patients, only 23.3% (14 of 60) continued olanzapine due to “benefits for positive symptoms” as a primary reason. There was a significant association between discontinuing the prior drug due to “positive symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” as a primary reason and continuing olanzapine due to “benefits for positive symptoms” as a primary reason (P = 0.027). The patients who discontinued the prior drug due to “positive symptoms not sufficiently improved or made worse” as a primary reason had about five times higher odds (odds ratio = 4.93, 95% confidence interval 1.22–19.98) of continuing with olanzapine due to “benefits for positive symptoms” as a primary reason than other patients.

Discussion

This study assessed the specific reasons patients and their clinicians reported for continuing or discontinuing olanzapine in the treatment of schizophrenia over a 22-week period. Using the recently validated RAD-I and RAD-Q measures,6 this study found that continuation of olanzapine appears to be driven primarily by efficacy, including general improvement perceived by patients, and improvement in positive symptoms and level of functioning. Discontinuing olanzapine in this study (30%) appeared to be primarily driven by lack of medication efficacy, especially on positive symptoms, followed by adverse events (eg, vomiting, nausea, tingling sensation in legs, dizziness, hyperglycemia, insomnia, oversleep, and somnolence) and insufficient improvement or worsening of negative symptoms according to the primary reasons given on the RAD measures. These results are consistent with a previous 12-week study of markedly ill schizophrenia patients experiencing acute psychotic exacerbations.4 That study also showed that patients and clinicians identified more reasons for the continuation of olanzapine than for its discontinuation (more than twice as many reasons), and there was a high level of concordance between patient and clinician perspectives on the reasons for medication continuation or discontinuation.

Participants in the previous study4 were acutely ill patients with schizophrenia who experienced a recent exacerbation of positive symptoms. These patients had a mean total Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale8 score of 54.4 and a CGI-S of 4.6. In contrast, the current study included patients who were less severely ill, all treated in outpatient settings, with Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and CGI-S mean scores of 46.9 and 4.0, respectively. Despite the differences in the illness severity profile of the patient populations, both studies demonstrated that continuation and discontinuation appear to be driven by medication efficacy for improving positive symptoms, whereas the reasons for medication discontinuation appear to be driven by both efficacy and medication-emergent adverse events. The replication of the previous findings in a less ill patient population suggests that the core reasons for continuing or discontinuing atypical antipsychotic medications can generalize across patient populations and are not unique to acutely ill psychotic patients with schizophrenia.

Current findings are also consistent with prior research demonstrating that continuing or discontinuing antipsychotic medications is driven primarily by medication efficacy.1,9–14 Although clinicians have long believed that medication safety and tolerability are the main drivers of medication discontinuation, the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study and other studies9 have shown the greater importance of efficacy. Recent studies have demonstrated that patient perceptions of medication benefits and treatment response (especially on positive symptoms) are robust predictors of treatment continuation/ discontinuation.4,10,15–17

A recent study by Campbell et al18 suggests that focus on a single symptom dimension or treatment-emergent adverse event may not fully capture the combination of variables that clinicians consider when prescribing antipsychotics. These investigators used a recently developed questionnaire (Antipsychotic Treatment Choice Questionnaire) to quantify risks and benefits that psychiatrists consider when choosing an antipsychotic medication. The prescribing decisions of four psychiatrists who initiated antipsychotic medication with 80 patients were examined. Results showed that the predicted certainty of symptom control and metabolic risk correlated significantly and independently with treatment decisions. A patient’s history of treatment response and severity of positive symptoms were frequently cited as most important by psychiatrists in making a treatment decision.

The findings of the present study need to be evaluated in the context of the study limitations. The most important limitation is that RAD results were not available for all patients who continued or discontinued the study medication. Despite a high study completion rate of 70%, only 50% of the patients who completed the study responded to the Reasons for Medication Continuation measure. Furthermore, only 40% of patients who discontinued the study completed the Reasons for Medication Discontinuation measure. There was no way to fill in missing data in the RAD, and data were not collected that would discern if patients refused to respond to the RAD or were lost to follow-up. This made it unfeasible to assess differences in reasons for discontinuation across time in this study. Because these patients were in an openlabel olanzapine study, they were choosing to participate and wanted to receive olanzapine treatment. This may have provided more reasons to continue with the study and may have added to the high completion rate. It should be pointed out that reasons for continuation or discontinuation may differ in those who are nonresponders to the measures given. In addition, excluding patients with diabetes also limits the generalizability of the results. Therefore, it is unclear whether reasons cited for medication continuation or discontinuation in this clinical trial differ from those reported in usual clinical practice.

In summary, the results from this study in an outpatient population with schizophrenia demonstrate that continuing or discontinuing olanzapine is primarily driven by medication efficacy. These results, in a less severely ill population, are consistent with results observed earlier in acutely ill psychotic patients with schizophrenia.

Conclusion

The main reason for continuing or discontinuing olanzapine appears to be medication efficacy, especially for positive symptoms. Reasons for medication discontinuation differ somewhat from reasons for continuation, with a high level of concordance between patient and clinician responses.

Footnotes

Disclosures

This work was supported by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN. All authors are either employees and minor shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company and/ or one of its subsidiaries or were when this study was conducted.

References

- 1.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matza LS, Phillips GA, Revicki DA, et al. Developing a clinician-reported measure of reasons for antipsychotic discontinuation or continuation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Presented at the Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum Biennial International Congress; Chicago, IL. July 9–13, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matza LS, Phillips GA, Revicki DA, et al. Developing a patient interview to assess reasons for antipsychotic discontinuation or continuation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(2):595–596. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ascher-Svanum H, Nyhuis A, Faries D, et al. Reasons for discontinuation and continuation of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia from patient and clinician perspectives. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(10):2403–2410. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.515900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffmann VP, Case M, Jacobson JG. Assessment of the safety, efficacy and practicality of treatment algorithms including amantadine, metformin, and zonisamide for the prevention of weight gain during treatment with olanzapine in outpatients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011 May 17; doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05580. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faries D, Ascher-Svanum H, Nyhuis A, Anderson J, Phillips G. The validation of a measure assessing reasons for antipsychotic discontinuation and continuation from patient’s and clinician’s perspectives. Presented at the Winter Workshop in Psychoses; Barcelona, Spain. November 15–18, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matza L, Phillips GA, Revicki D, et al. Development of a clinician questionnaire and patient interview to assess reasons for antipsychotic discontinuation. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189(3):463–468. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu-Seifert H, Adams DH, Kinon BJ. Discontinuation of treatment of schizophrenic patients is driven by poor symptom response: a pooled post-hoc analysis of four atypical antipsychotic drugs. BMC Med. 2005;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perkins DO, Gu H, Weiden PJ, McEvoy JP, Hamer RM, Lieberman JA. Predictors of treatment discontinuation and medication nonadherence in patients recovering from a first episode of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or schizoaffective disorder: a randomized, double-blind, flexible-dose, multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):106–113. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkins DO, Johnson JL, Hamer RM, et al. Predictors of antipsychotic medication adherence in patients recovering from a first psychotic episode. Schizophr Res. 2006;83(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossi A, Vita A, Tiradritti P, Romeo F. Assessment of clinical and metabolic status, and subjective well-being, in schizophrenic patients switched from typical and atypical antipsychotics to ziprasidone. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(4):216–222. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f94905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenheck R, Chang S, Choe Y, et al. Medication continuation and compliance: a comparison of patients treated with clozapine and haloperidol. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(5):382–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loffler W, Kilian R, Toumi M, Angermeyer MC. Schizophrenic patients’ subjective reasons for compliance and noncompliance with neuroleptic treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(3):105–112. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu-Seifert H, Houston JP, Adams DH, Kinon BJ. Association of acute symptoms and compliance attitude in noncompliant patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(4):392–394. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000264986.32733.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karow A, Czekalla J, Dittmann RW, et al. Association of subjective well-being, symptoms, and side effects with compliance after 12 months of treatment in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(1):75–80. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinon BJ, Chen L, Ascher-Svanum H, et al. Early response to antipsychotic drug therapy as a clinical marker of subsequent response in the treatment of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;35(2):581–590. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell EC, Dejesus M, Herman BK, et al. A pilot study of antipsychotic prescribing decisions for acutely-ill hospitalized patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(1):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]