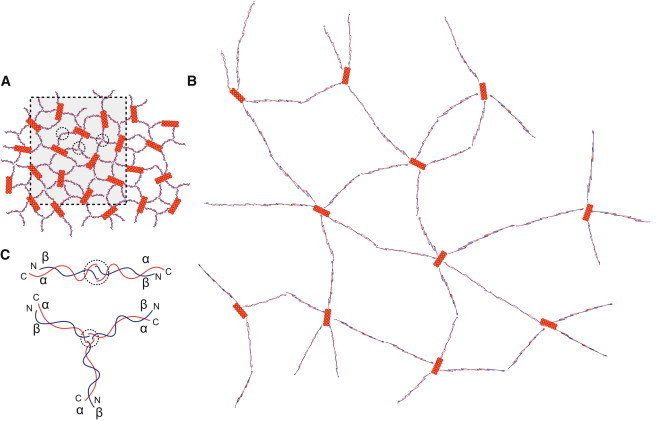

Figure 8.

Model for transition between the intact and expanded forms of the erythrocyte membrane skeleton. (A) Our model of the unexpanded membrane skeleton, which is consistent with cryo-electron tomography of frozen-hydrated preparations of intact skeletons. This model is composed of spectrin molecules (thin red and blue strands) connecting junctional complexes (orange filaments). Spectrin heterodimers composed of α- (red) and β (blue)-chains are connected to each junctional complex. Higher-order tetramers, hexamers, and octamers are formed by self-association sites halfway between the junctional complexes (circles). Our data suggest that these self-association sites are transient and that coupling between individual spectrin molecules is continually being reconfigured. (B) Model of the expanded skeleton that is consistent with electron tomography of sheared skeletons that were adsorbed to the carbon support. This model represents an expansion of the boxed region in A and is drawn at the same scale. Expansion produces a lower surface density of spectrin molecules, which we believe accounts for the observed shift of higher-order spectrin oligomers (hexamers and octamers) toward the tetrameric form, which is fully extended. Thus, the dynamic equilibrium of the spectrin network allows the erythrocyte to undergo large deformations in response to shear force. (C) Schematic representations of a spectrin heterotetramer (upper) and hexamer (lower). Heterotetramers are formed through an exchange of α-helices from the N- and C-termini of α- and β-spectrin, respectively (overlap of chains inside the circle). Higher-order oligomers, such as hexamers and octamers, can be formed in a similar manner, except that the α- and β-spectrin molecules pair with α- and β-spectrin molecules that originate from different heterodimers.