Abstract

Background

Heavy metals, especially copper, nickel, lead and zinc, have adverse effects on terrestrial and in aquatic environments. However, their impact can vary depending on the nature of organisms. Taking into account the ability of heavy metals to accumulate in sediments, extended knowledge of their effects on aquatic biota is needed. In this context the use of model organisms (often unicellular), which allows for rapid assessment of pollutants in freshwater, can be of advantage. Pentachlorophenol has been extensively used for decades as a bleaching agent by pulp- and paper industry. Pentachlorophenol tends to accumulate in the nature. We aim to determine if photosynthesis and motility can be used as sensitive physiological parameters in toxicological studies of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a motile green unicellular alga. It is discussed if photosynthesis and motility can be used as sensitive physiological parameters in toxicological studies.

Results

The concentrations studied ranged from 0.1 to 2.0 mg l-1 for copper, nickel, lead and zinc, and from 0.1 to 10.0 mg l-1 for pentachlorophenol. Exposure time was set to 24 h. Copper and pentachlorophenol turned out to be especially toxic for photosynthetic efficiency (PE) in C. reinhardtii.

Conclusion

Copper and pentachlorophenol turned out to be especially toxic for PE in C. reinhardtii. Zinc has been concluded to be moderately toxic while nickel and lead had stimulatory effects on the PE. Because of high variance, motility was not considered a reliable physiological parameter when assessing toxicity of the substances using C. reinhardtii.

Background

Heavy metals, especially copper, nickel, lead and zinc, have adverse effects on terrestrial and in aquatic environments. However, their impact can vary depending of the nature of organisms [1, 2]. Taking into account the ability of heavy metals to accumulate in sediments, extended knowledge of their effects on aquatic biota is needed [3]. In this context the use of model organisms, which allow for rapid assessment of pollutants in freshwater, can be of advantage. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii has been shown to be one of those especially suited organisms for different kinds of studies [4, 5]. Previous investigations showed C. reinhardtii to be sensitive to copper, nickel and zinc [6,7,8,9]. Although, most studies concentrated on the impacts on growth rates and ultrastructure. The photosynthetic apparatus in C. reinhardtii was shown to be highly vulnerable to toxic substances thus making it a suitable parameter for toxicity estimation [10,11,12]. Motility has been shown to be one of the possible physiological markers for toxicity assessment using Euglena gracilis [13]. The aim of this study was to carry out comprehensive experiments in order to investigate effects of different concentrations of copper, nickel, lead and zinc on the photosynthetic efficiency and motility of C. reinhardtii. As an additional test substance pentachlorophenol was used to its previous use as a bleaching agent at pulp and paper factories in Sweden thus making it to a spread contaminant in some areas.

Results and Discussion

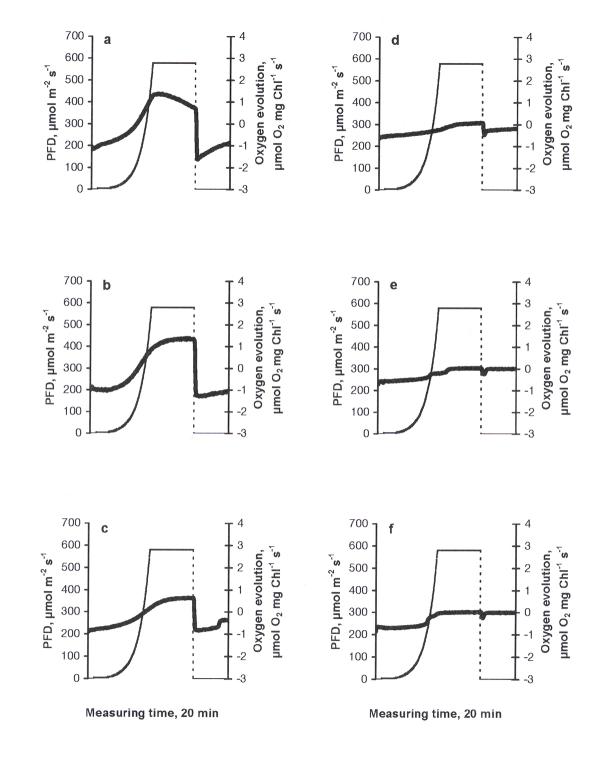

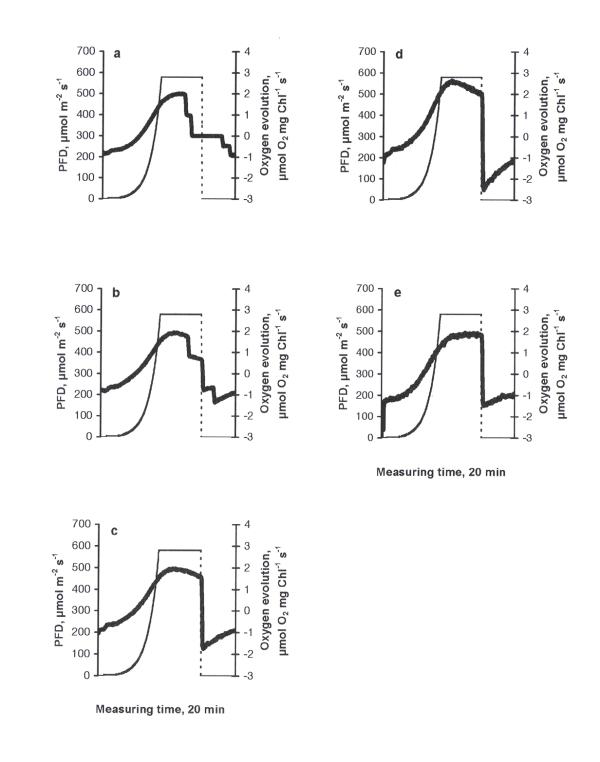

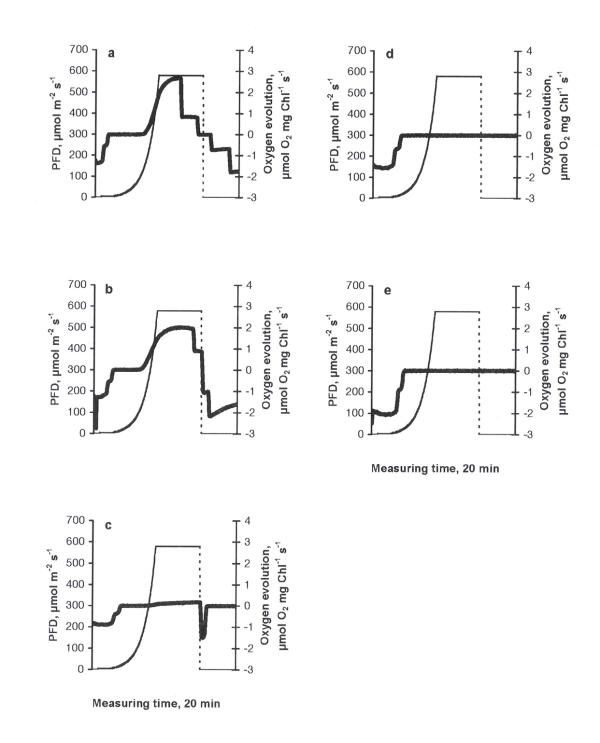

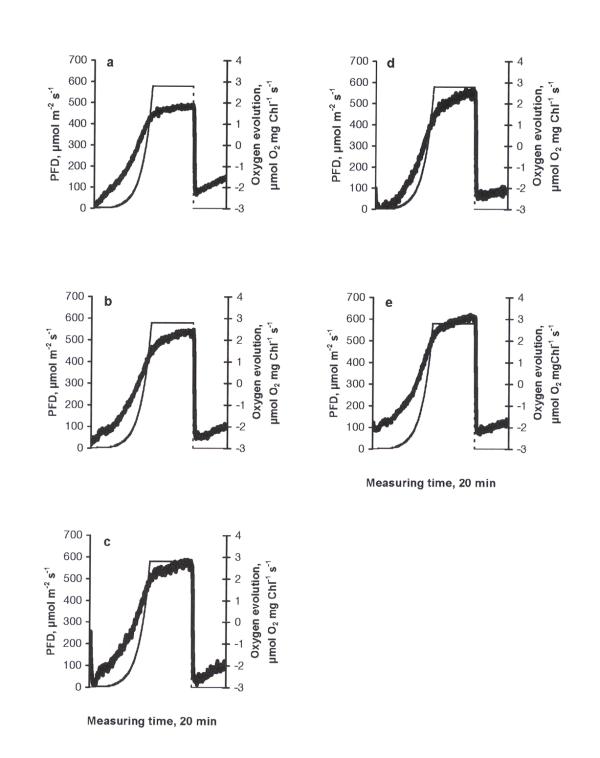

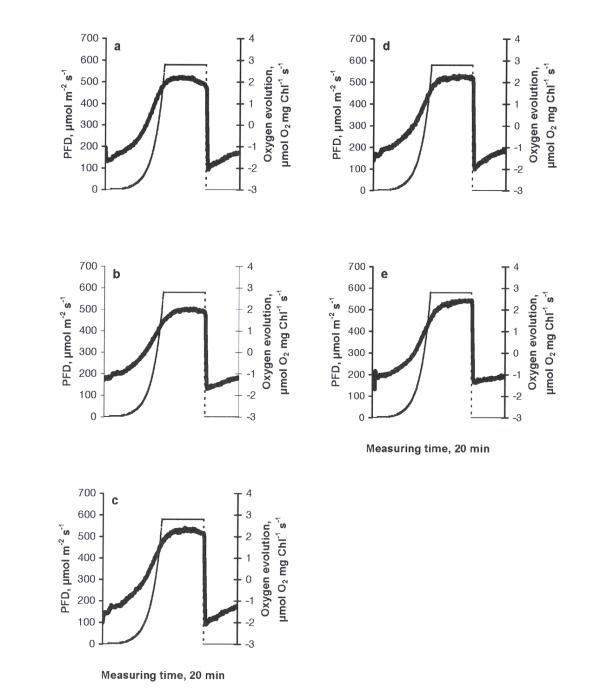

The photosynthetic response curve (PRC) of the control was characterised by an increase in oxygen evolution according to the increase in PFD up to 612 μmol m-2 s-1 (the highest PFD-value used in the experiments) and a decrease in oxygen evolution due to the inhibition of photosynthesis when PFD became constant (612 μmol m-2 s-1, Fig. 1a). A peak of higher respiration immediately after the cessation of illumination can be explained by the light-enhanced dark respiration (LEDR, the rate of change of oxygen consumption - an acceleration), which contributed to the basal dark respiration. The behaviour of PRC is important evidence of how favourable the conditions are for photosynthesis [14]. The type of PRC described above was found in similar investigations to be typical in the green flagellate Euglena gracilis [15]. Similarly, this type of PRC can be considered as common in C. reinhardtii, too. At all treatments this basic type of PRC was observed. The stepwise drop in oxygen evolution at the maximum irradiance value in fig. 3a,b and fig. 5a,b should be considered as an artefact specific to the Light Pipette model used (when the value of oxygen saturation in the cuvette exceeds 200 %, unpublished results of a methodical study). Increasing concentrations of copper led to decrease in maximum values of oxygen evolution compared to the control, demonstrating especially severe impacts at the concentrations of 0.5 mg l-1 and higher (Fig. 1b,c,d,e,f). The treatments with nickel, lead or zinc did not caused such strong inhibitory effects as in the case of copper. Moreover, in the case of nickel (Fig. 2) maximum values of oxygen evolution were higher than those in the control and no inhibition of photosynthesis was observed when the PFD became constant (612 μmol m-2 s-1). Increasing concentrations of nickel seemed to be stimulative based on the shape of PRCs. Only slight inhibition of photosynthesis at the constant maximal PFD values was detected in the cases of lead or zinc treatments (Figs. 3, 4, respectively) and maximum values of oxygen evolution were equal to or higher than in the control. The treatment with pentachlorophenol led to prolongated compensation points at lower concentrations (0.1 and 0.5 mg l-1) and to severe impacts on photosynthesis at concentrations of 1.0 mg l-1 and higher (Fig. 5) comparable to those caused by copper treatments.

Figure 1.

The dependence of photosynthetic response curves in C. reinhardtii to different concentrations of copper (mg l-1) after 24 h exposure: a) control, b) 0.1, c) 0.5, d) 1.0, e) 1.5, f) 2.0. Thick solid line - oxygen evolution, thin dashed line - light evolution.

Figure 3.

The dependence of photosynthetic response curves in C. reinhardtii to different concentrations of lead (mg l-1) after 24 h exposure: a) 0.1, b) 0.5, c) 1.0, d) 1.5, e) 2.0. Thick solid line - oxygen evolution, thin dashed line - light evolution.

Figure 5.

The dependence of photosynthetic response curves in C. reinhardtii to different concentrations of pentachlorophenol (mg l-1) after 24 h exposure: a) 0.1, b) 0.5, c) 1.0, d) 5.0, e) 10.0. Thick solid line - oxygen evolution, thin dashed line - light evolution.

Figure 2.

The dependence of photosynthetic response curves in C. reinhardtii to different concentrations of nickel (mg l-1) after 24 h exposure: a) 0.1, b) 0.5, c) 1.0, d) 1.5, e) 2.0. Thick solid line - oxygen evolution, thin dashed line - light evolution.

Figure 4.

The dependence of photosynthetic response curves in C. reinhardtii to different concentrations of zinc (mg l-1) after 24 h exposure: a) 0.1, b) 0.5, c) 1.0, d) 1.5, e) 2.0. Thick solid line - oxygen evolution, thin dashed line - light evolution.

Because of often similar behaviour of PRCs, such parameters as photosynthetic efficiency (PE) and compensation point (CP) became important when comparing how favourable conditions for photosynthesis are after different treatments studied. PE measured as slope coefficients showed negative correlation with increasing concentrations of copper, zinc and pentachlorophenol (Tab. 1). While the decrease in PE could be predicted from the behaviour of PRCs by treatments with copper and pentachlorophenol, negative effects of increasing concentrations of zinc were not so obvious where all values of PE exceeded those of the control. Increasing concentrations of nickel and lead correlated positively with PE in C. reinhardtii. Thereby, in case of nickel all coefficients were higher than that in the control while in case of lead coefficients both below and above that in the control were observed.

Table 1.

Effects of different concentrations of heavy metals and pentachlorophenol (Pent.) on the photosynthetic efficiency (slope coefficients) of C. reinhardtii after 24 h exposure.

| Concentration, | Substances | ||||

| mg l-1 | Copper | Nickel | Lead | Zinc | Pent. |

| 0.0 | 0.140 | 0.140 | 0.140 | 0.140 | 0.140 |

| 0.1 | 0.131 | 0.232 | 0.150 | 0.224 | 0.098 |

| 0.5 | 0.055 | 0.228 | 0.133 | 0.153 | 0.090 |

| 1.0 | 0.015 | 0.251 | 0.138 | 0.180 | 0.002 |

| 1.5 | 0.026 | 0.267 | 0.176 | 0.174 | |

| 2.0 | 0.047 | 0.244 | 0.160 | 0.165 | |

| 5.0 | 0.014 | ||||

| 10.0 | 0.014 | ||||

| R | - 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.60 | - 0.54 | - 0.83 |

R - coefficient of correlation between increasing concentrations of the substances tested and the photosynthetic efficiency.

The capacity of copper to inhibit photosynthesis has been reported previously for some algae [16, 17]. Inhibition capacity of nickel, lead and zinc on different physiological parameters and photosynthesis in algae have been detected in earlier studies [9, 18,19,20,21,22,23]. Pentachlorophenol has been shown to be a severe environmental poison [24]. Based on the PE, our results let us conclude copper and pentachlorophenol to be especially toxic to the photosynthetic apparatus in C. reinhardtii. These results are in good agreement with the high inhibition capacity of copper to C. reinhardtii reported in other studies [7, 9, 11, 25]. Nickel and lead can be concluded to have stimulatory effects on the PE in C. reinhardtii. This fact can be explained by a possible short-term stimulatory effect of some usually toxic substances reported for some unicellular algae. This effect depends both on the nature of organism and of the exposure duration [26, 27].

Positive correlations were detected between CPs and increasing concentrations of copper, lead, zinc and pentachlorophenol (Tab. 2). In the cases of lead, zinc and pentachlorophenol, CPs were lower than in the control. When exposed to a stress, organism may need higher light intensity to reach the CP [14]. However, this trend is widely general and should be considered rather as a rule of thumb [15]. As pointed out by Ögren and Evans [14], both PE and CP are valuable indicators of how favourable conditions for photosynthesis are. On the other hand, it is not clear how efficient these parameters are when assessing the capacity to photosynthesise. Our previous results obtained on E. gracilis showed that discrepancies between trends in PE (measured as slope coefficients) and CPs could occur quite often [15]. Thus the question which parameter should be considered as more efficient still remains open. Our current opinion is that the PE provides more relevant information about the physiological state of the photosynthetic apparatus. However, more research is highly desirable to solve this question.

Table 2.

Effects of different concentrations of heavy metals and pentachlorophenol (Pent.) on the compensation points (CP, μmol m-2 s-1) of photosynthesis in C. reinhardtii after 24 h exposure.

| Concentration, | Substances | ||||

| mg l-1 | Copper | Nickel | Lead | Zinc | Pent. |

| 0.0 | 118 | 118 | 118 | 118 | 118 |

| 0.1 | 162 | 126 | 61 | 88 | 19 |

| 0.5 | 366 | 165 | 48 | 85 | 48 |

| 1.0 | 579 | 132 | 48 | 98 | 29 |

| 1.5 | 579 | 192 | 38 | 83 | |

| 2.0 | 579 | 105 | 98 | 108 | |

| 5.0 | 21 | ||||

| 10.0 | 31 | ||||

| R | 0.87 | 0.45 | 0.58 | ||

R - coefficient of correlation between increasing concentrations of the substances tested and the CPs. Absolute values of R below 0.15 are not shown.

The calculated motility values showed high variance (Tab. 3). Only at the concentrations of pentachlorophenol of 5.0 and 10.0 mg l-1 the differences were significantly different (t-test). Hence, we do not consider motility in C. reinhardtii as a reliable parameter for toxicity testing. This is in disagreement with a general proposal of Häder et al. [13] to use motility as a valuable parameter in bioassays.

Table 3.

Effects of different concentrations of heavy metals and pentachlorophenol (Pent.) on the cell motility (m s-1) of C. reinhardtii after 24 h exposure.

| Concentration, | Substances | ||||

| mg l-1 | Copper | Nickel | Lead | Zinc | Pent. |

| 0.0 | 46.6 ± 34.9 | 46.6 ± 34.9 | 46.6 ± 34.9 | 46.6 ± 34.9 | 46.6 ± 34.9 |

| 0.1 | 26.6 ± 18.7 | 26.3 ± 17.8 | 33.1 ± 22.1 | 26.5 ± 16.6 | 52.1 ± 49.9 |

| 0.5 | 31.2 ± 26.3 | 31.2 ± 27.4 | 33.9 ± 21.5 | 27.8 ± 19.3 | 56.7 ± 41.9 |

| 1.0 | 25.4 ± 12.8 | 27.0 ± 18.6 | 40.0 ± 33.8 | 34.0 ± 24.5 | 53.1 ± 36.7 |

| 1.5 | 34.0 ± 25.5 | 32.2 ± 24.4 | 47.4 ± 38.7 | 29.3 ± 22.2 | |

| 2.0 | 28.9 ± 20.6 | 37.1 ± 28.3 | 46.4 ± 34.9 | 35.1 ± 26.1 | |

| 5.0 | 0 | ||||

| 10.0 | 0 | ||||

Values of standard deviation are shown.

Conclusions

Copper and pentachlorophenol turned out to be especially toxic for PE in C. reinhardtii. Zinc has been concluded to be moderately toxic while nickel and lead had stimulatory effects on the PE. Because of high variance, motility was not considered a reliable physiological parameter when assessing toxicity of the substances using C. reinhardtii.

Material and methods

One-week old cultures of C. reinhardtii (strain 137c mt+, Stefan Falk, Mid Sweden University, Östersund, Sweden) were used in the experiments. The strain has been grown for many years by the mentioned researcher and has been previously isolated from an intact site (no pollution). Algae were in the exponential growth phase when the experiments were started. Starting density of the cells was held at 10,000 cells ml-1. Freshwater medium described by Checcucci et al. [28] was used for cultures. The cells of C. reinhardtii were grown in 100 ml Erlenmeyer glass flasks at 20°C in a cultivation cabinet (Termax Klimatskåp, 6395 F/FL, Ninolab AB). The light/dark cycle was 16 h/8 h with an irradiance of 70 μmol m-2 s-1 (400-700 nm). The cells were exposed for 24 h to heavy metals as Cu2+, Ni2+, Pb2+ and Zn2+ at the concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 mg l-1, respectively. Pentachlorophenol concentrations were 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0 and 10.0 mg l-1.

For each concentration studied the measurements were repeated three times and the mean values from the three replicates were calculated. Photosynthesis and respiration were measured as the rate of oxygen evolution/consumption per gram (g) chlorophyll and time (s-1) with a Light Pipette (Brammer, Illuminova, Uppsala, Sweden). The instrument consists of a light source that is connected to a cuvette with a micro-oxygen electrode (MI-730, Microelectrodes, Inc., 298 Rockingham Rd., Londonderry, NI), a quantum sensor, a temperature-controlled water bath and a computer. The light source provides precise photon flux density (PFD) of 0 to 3500 (μmol m-2 s-1). The rate of oxygen evolution was calculated on the basis of the ambient O2 concentration of 0.276 μmol ml-1, which in this investigation corresponds to 100%. Chlorophyll was estimated by extraction in 80% acetone solution and its absorbance was measured with a spectrophotometer (UV/VIS spectrometer Lambda Bio 20, PERKIN ELMER) at 652 nm. Chlorophyll content was measured according to the following equation:

Chl (mg ml-1) = A652/34.5,

where A652 corresponds to absorbance at 652 nm and 34.5 is the absorbance of 1 mg ml-1 Chl extracted in 80% acetone.

The cells of C. reinhardtii were placed in the cuvette and each measurement of oxygen evolution/consumption lasted for 20 min at 20°C. The photon flux density (PFD) provided by the light source continuously increased during 9 min from 0 up to 612 μmol m-2 s-1, remained unchanged for 6 min and was then turned off (darkness) for 5 min (Figure 1a). Measuring oxygen evolution for 20 min produced 600 measuring points at a rate of 5 Hz and every point represented the average of five subsamples. The photosynthetic efficiency (PE, the increase in photosynthetic rate vs. time immediately after illumination) was calculated as the slope coefficients of the photosynthetic curves between 20 and 500 μmol m-2s-1. The slope of the photosynthesis-irradiance curve is proportional to the maximum quantum yield of photosynthesis [29]. It means that a quicker increase in oxygen evolution would result in a higher coefficient.

A compound microscope Nikon Optiphot connected to a video CCD Camera Ikegami ICD-44L (Ikegami Tsushinki Co., Ltd., Japan) was used to study the motility of C. reinhardtii. The image was translated to a PC. All calculations were processed with Motile System V. 1.7 (motility) software developed by D.-P. Häder and K. Vogel, Erlangen, Germany [13]. The motility was measured in term of μm s-1. An average value from 2000 measurements was calculated in each measurement. All statistical analyses were performed in the computer package Minitab 11.0.

Contributor Information

Roman A Danilov, Email: roman.danilov@tnv.mh.se.

Nils GA Ekelund, Email: nils.ekelund@tnv.mh.se.

References

- Clark RB. Marine pollution. 4th edition, Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1997.

- Seidl M, Huang V Mouchel JM. Toxicity of combined sewer overflows on river phytoplankton: the role of heavy metals. Environ Pollut. 1998;101:107–116. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(98)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M, Korhola A, Seppa H, Virkanen J. A long-term record of human impacts on an urban ecosystem in the sediments of Toolonlahti Bay in Helsinki, Finland. Environ Conserv. 1997;24:326–337. doi: 10.1017/S037689299700043X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rochaix JD. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as the photosynthetic yeast. Ann Review Genet. 1995;29:209–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JP, Grossman AR. The use of Chlamydomonas (Chlorophyta: Volvocales) as a model algal system for genome studies and the elucidation of photosynthetic processes. J Phycol. 1998;34:907–917. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.1998.340907.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey JE, Owen HA, Winner RW. Toxicity of copper to the green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Chlorophyceae), as affected by humic substances of terrestrial and fresh water origin. Aquat Toxicol. 1991;19:89–96. doi: 10.1016/0166-445X(91)90029-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winner RW, Owen HA. Toxicity of copper to Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Chlorophyceae) and Ceriodaphnia dubia (Crustaceae) in relation to changes in water chemistry of a fresh water pond. Aquat Toxicol. 1991;21:157–170. doi: 10.1016/0166-445X(91)90070-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macfie SM, Tarmohamed Y, Welbourn PM. Effects of cadmium, cobalt, copper, and nickel on growth of the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii - the influences of the cell wall and pH. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1994;27:454–458. [Google Scholar]

- Sunda WG, Huntsman SA. Interactions among Cu2+, Zn2+, and Mg2+ in controlling cellular Mn, Zn, and growth rate in the coastal alga Chlamydomonas. Limnol Oceanogr. 1998;43:1055–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Draber W, Hilp U, Likusa H, Schindler M, Trebst A. Inhibition of photosynthesis by 4-nitro-6-alkylphenols - structure activity studies in wild type and 5 mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii thylakoids. Z Naturforsch C. 1993;48:213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Hill KL, Merchant S. Coordinate expression of coproporphyrinogen oxidase and cytochrome C6 in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in response to changes in copper availability. EMBO J. 1995;14:857–865. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RE, Thomas DJ, Tucker DE, Herbert SK. The effects of photooxidative stress on photosystem I measured in vivo in Chlamydomonas. Plant Cell Develop. 1997;20:1451–1461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-47.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Häder D-P, Lebert M, Tahedl H, Richter P. The Erlanger flagellate test (EFT): photosynthetic flagellates in biological dosimeters. J Photochem Photobiol. 1997;40:23–28. doi: 10.1016/S1011-1344(97)00028-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ögren E, Evans JR. Photosynthetic light-response curves. Planta. 1993;189:182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Danilov RA, Ekelund NGA. Influence of waste water from the paper industry and UV-B radiation on the photosynthetic efficiency of Euglena gracilis. J App Phycol. 1999;11:157–163. doi: 10.1023/A:1008032211771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cid A, Herrero C, Torres E, Abalde J. Copper toxicity on the marine microalga Phaeodactylum tricornutum - effects on photosynthesis and related parameters. Aquat Toxicol. 1995;31:165–174. doi: 10.1016/0166-445X(94)00071-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nalewajko C, Olaveson MM. Differential responses of growth, photosynthesis, respiration, and phosphate-uptake to copper in copper tolerant and copper-intolerant strains of Scenedesmus acutus (Chlorophyceae). Can J Bot. 1995;73:1295–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro L, Torres-Marquez M, Gonzalez-Moreno S, Devars S, Hernandez R, Moreno-Sanchez R. Comparison of physiological changes in Euglena gracilis during exposure to heavy metals of heterotrophic and autotrophic cells. Comp Biochem Physiol, A: 1997;116:265–272. doi: 10.1016/S0742-8413(96)00202-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd-El-Monem HM, Corradi MG, Gorbi G. Toxicity of copper and zinc to two strains of Scenedesmus acutus having different sensitivity to chromium. Environ Exp Bot. 1998;40:59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0098-8472(98)00021-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angadi SB, Mathad P. Effect of copper, cadmium and mercury on the morphological, physiological and biochemical characteristics of Scenedesmus quadricauda (Turp.) de Breb.. J Environ Biol. 1998;19:119–124. [Google Scholar]

- El-Naggar AH. Toxic effects of nickel on photosystem II of Chlamydomonasreinhardtii. Cytobios. 1998;93:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fargasova A. Accumulation and toxin effects of Cu2+, Cu+, Mn2+, VO43-, Ni2+ and MoO42- and their associations: influence on respiratory rate and chlorophyll a content of the green alga Scenedesmus quadricauda. J Trace Microprobe Tech. 1998;16:481–490. [Google Scholar]

- Zeisler R, Dekner R, Zeiller E, Doucha J, Mader P, Kucera J. Single cell green algae reference materials with managed levels of heavy metals. Fresenius J Anal Chem. 1998;360:429–432. doi: 10.1007/s002160050729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tikoo V, Shales SW, Scragg AH. Effect of pentachlorophenol on the growth of microalgae. Environ Technol. 1996;17:1139–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Visviki I, Rachlin JW. Acute and chronic exposure of Dunaliella salina and Chlamydomonas bullosa to copper and cadmium - effects on ultrastructure. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1994;26:154–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00224799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargasova A, Kizlink J. Effect of organotin compounds on the growth of the freshwater alga Scenedesmus quadricauda. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1996;34:156–159. doi: 10.1006/eesa.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignoles P, Greyfuss G, Rondelaud D. Growth modification of Euglena gracilis Klebs after 2-benzamino-5-nitrothiazole derivates application. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1996;34:118–124. doi: 10.1006/eesa.1996.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checcucci A, Colombetti G, Ferrara R, Lenci F. Action spectra for photoaccumulation of green and colorless Euglena : evidence for identification of receptor pigments. Photochem Photobiol. 1976;23:51–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1976.tb06770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt T, Jassby A. The relationship between photosynthesis and light for natural assemblages of coastal marine phytoplankton. J Phycol. 1976;12:421–430. [Google Scholar]