Abstract

Objectives. The Community Action to Fight Asthma Initiative, a network of coalitions and technical assistance providers in California, employed an environmental justice approach to reduce risk factors for asthma in school-aged children. Policy advocacy focused on housing, schools, and outdoor air quality. Technical assistance partners from environmental science, policy advocacy, asthma prevention, and media assisted in advocacy. An evaluation team assessed progress and outcomes.

Methods. A theory of change and corresponding logic model were used to document coalition development and successes. Site visits, surveys, policymaker interviews, and participation in meetings documented the processes and outcomes. Quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed to assess strategies, successes, and challenges.

Results. Coalitions, working with community residents and technical assistance experts, successfully advocated for policies to reduce children's exposures to environmental triggers, particularly in low-income communities and communities of color. Policies were implemented at various levels.

Conclusions. Environmental justice approaches to policy advocacy could be an effective strategy to address inequities across communities. Strong technical assistance, close community involvement, and multilevel strategies were all essential to effective policies to reduce environmental inequities.

Incorporating environmental justice into strategies to reduce health disparities involved identifying the root causes of social inequalities, building upon community democratic decision-making processes, and identifying environmental health hazards—and connecting all of these to public health outcomes.1,2 By addressing interconnections among environmental exposures, socioeconomic and structural factors, and biological processes, an environmental justice framework was a powerful tool for addressing health inequities. Through increased understanding of the political and economic forces that contributed to environmental inequalities, and by working closely with residents and local organizations, researchers, advocates, and policymakers, coalitions reduced environmental health inequities.

Childhood asthma provided a particularly dramatic example of the interrelationships between environmental risk factors, socioeconomic vulnerability, and poor health. Known environmental risk factors, or “triggers,” of asthma included outdoor air pollution from freeways, railways, and pesticides; other mobile and stationary sources of pollution; indoor air pollution resulting from mold, mildew, and poor ventilation in substandard housing or school facilities; allergens (e.g., dust mites, cockroaches and rodent dander); and cleaning products and other chemicals.3–7 Low-income children and children of color were more likely than others to have asthma; they were also more likely to live in substandard housing and be exposed to environmental toxins in their homes, schools, and communities.8–12 In California, for example, it was common to see asthma prevalence rates that varied 2- to 3-fold, depending upon geography, racial/ethnic composition, and economic status of the communities being compared.13–15

Despite the traditional societal focus on individual level factors in determining risk for asthma and other chronic conditions, emerging research suggested that neighborhood settings and other community level factors played a substantial role in shaping health status.16–22 Historically, community initiatives to reduce asthma disparities among children often failed to address the environmental justice component of eliminating asthma triggers, or to create policy change aimed at the environmental root causes. The complexity of the roots of asthma disparities demanded a multifactorial, multilevel, and interdisciplinary approach.23–25 To effectively identify and address problems, develop appropriate strategies, and ensure lasting change, interventions to ameliorate asthma disparities required community involvement at each stage.3,26–28

This article describes the strategies implemented, outcomes achieved, and lessons learned from a statewide community-based environmental justice and policy advocacy initiative developed to reduce environmental asthma triggers for California children.

METHODS

In 2002, The California Endowment (TCE), California's largest health foundation, launched the Community Action to Fight Asthma Initiative (CAFA) to develop a network of community organizations working to reduce community environmental asthma risk factors. Over 8 years, TCE funded between 9 and 12 local coalitions, composed of American Lung Association (ALA) affiliates, local health clinics, other asthma- or health-related organizations, and community organizations and members. Technical assistance was provided by statewide experts in asthma prevention and management, policy advocacy, and media and communication. Technical assistance providers included Regional Asthma Management and Prevention (RAMP), the National Latino Research Center, Physicians for Social Responsibility, the Central California Asthma Project, Community Health Works, PolicyLink, the Public Media Center, and evaluators from the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

Logic Model

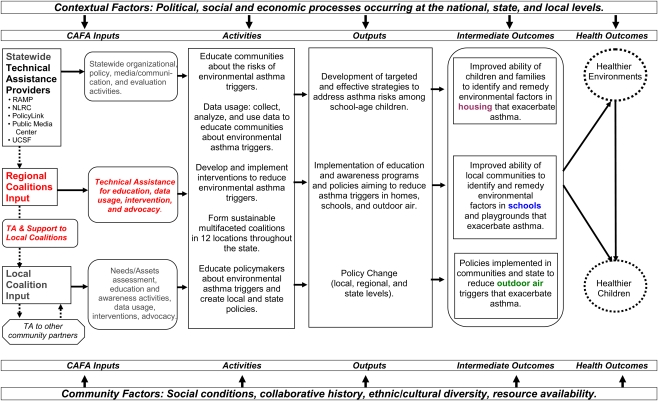

The initiative aimed to build the capacity and strength of each local coalition while integrating and uniting efforts across the entire network through a strategic focus on policy advocacy. The initiative employed a logic model developed by UCSF, in conjunction with the foundation and the CAFA grantees that reflected the contextual, community, and other inputs that influenced children's health outcomes (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Community Action to Fight Asthma (CAFA) logic model to reduce environmental risk factors for school-aged children with asthma.

Note. NLRC = National Latino Research Center; RAMP = Regional Asthma Management and Prevention; TA = technical assistance; USCF = University of California, San Francisco.

Each coalition undertook a range of activities, such as educating and mobilizing community members and policymakers, forming collaborations with other organizations, collecting and disseminating data on environmental triggers, and developing and implementing policies to reduce environmental triggers at the local, regional, and state levels. Through collaborative processes, the coalitions defined 3 topics on which to focus activities: housing, schools, and outdoor air quality (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Community Action to Fight Asthma (CAFA) Coalition Activities by Type, 2002–2010

| Coalition Activities | Examples of Activities |

| Coalition Building | |

| Skill building Finding partners Defining joint projects | Attend trainings with technical assistance experts to learn skills in data collection and analysis, improved community education methods focused on policy, fundraising, and outreach strategies. Conduct outreach to community and environmental partners, health care providers, and others. Attend local meetings of air quality boards, school boards, health departments, housing authorities, etc., to identify mutual interests. |

| Community and policymaker education related to environmental justice policies | Provide resident education regarding environmental risk factors on asthma and policies that affect these factors. Conduct advocacy training for residents. Provide information and data on asthma and air quality to residents. |

| Data collection and analysis | Collect data on collaboration among coalitions and partners. Collect data on indicators of policy change across multiple levels of the initiative. Report quantitative and qualitative data on policy strategies and outcomes. |

| Multilevel environmental justice policy advocacy | |

| Housing | Educate policymakers about environmental risk factors of asthma. Create standard procedure for use of thermographic cameras in Housing. Authority to improve remediation and reduce in-home risk factors. Create legal precedents and regulations to reduce substandard housing conditions. Train local community health workers (promotoras) to conduct indoor air quality assessments in homes. |

| Schools | Design guidelines for school renovation to reduce moisture and improve ventilation. |

| Outdoor air quality | Implement asthma action plans in schools to reduce environmental risk factors in homes, schools, and outdoors. Implement anti-idling regulations for school buses. Promote rerouting of freeways away from low-income communities and communities of color. Implement wood burning ordinances to reduce particulate matter. Reduce truck, railyard, and ship pollution from ports. |

Model of Change

Through the initiative, coalitions progressed through the Stages of Collaborative Development for Systems Change, developed by Brindis and Wunsch.29 The 4 stages are (1) information exchange, (2) development of joint projects, (3) reducing barriers or rules preventing successful outcomes for the joint project, and (4) considering required broader systemic change.

UCSF also used the Lafferty and Mahoney framework to track the indicators of environmental justice policy and systems change,30 including a continuum of community activities and outcomes to document how collaboratives progressed across multiple sectors, from changing individual and family behaviors to more institutionalized organizational and sustainable systems change. In contrast to other models, the community was an integral partner at the inception of the endeavor.31

Evaluating Environmental Policy Change

In 2003, UCSF joined the initiative to measure its local and statewide impact, assess challenges and successes in its implementation, and identify strategies that proved particularly effective for the coalitions. Specifically, UCSF focused on answering: (1) what approaches were most important in supporting communities to create policies that reduced environmental asthma risk factors and create systems change, and (2) what were the outcomes (short, intermediate, and longer term) of these policy endeavors.

Table 2 presents the qualitative and quantitative evaluation methods used, including type of instruments, data source, and examples of data collected.

TABLE 2.

Selected Methods Used to Evaluate the Community Action to Fight Asthma (CAFA) Initiative: California, 2002–2010

| Evaluation Activities (No. or Timeframe) | Evaluation Method Type (Type of Data Collected) | Examples of Data Collected |

| Annual site visits to coalitions and technical assistance partners (11–12/y) | Process evaluation (qualitative and quantitative) | What are the important partnerships that your coalition has formed or attempted? Why did the coalition decide to pursue these partnerships? What are the results of these partnerships? What type of assistance have you received from your local technical assistance partner? Facilitating networking and collaboration; Developing advocacy and policy strategies; and Responding to needs for data and analysis. How helpful was the assistance you received? What challenges has the coalition faced? How has the coalition dealt with these challenges? What media or communication strategies have you employed? On which audiences have you focused? What outcomes have you seen from these efforts? |

| Review of semiannual grantee reports to the evaluation team (ongoing, every 6 mo) | Process and outcome evaluation (qualitative and quantitative) | List of collaborative activities and partners. Individual, community, organizational, policy level outcomes. Use of media and technology in CAFA activities. Policy indicators and outcomes. |

| Interviews with policymakers and stakeholders (20–35 every 2 to 3 y) | Process and outcome evaluation (qualitative and quantitative) | How familiar are you with the following environmental issues related to asthma? Indoor air quality in homes; Indoor air quality in schools; and Outdoor air quality. In the last 3 years, has your awareness of this issue changed? In what capacity have you worked on these issues with CAFA coalitions? |

| Collaboration survey among coalitions (20–50/y) | Process and outcome evaluation of collaboration (qualitative and quantitative) | Is there is any sector, agency, organization, or group of individuals that need to be recruited to make this partnership most diverse and representative of the community? Please indicate how much has this partnership accomplished in the following fields: Involving people of color and other minorities in regular activities? Creating a board reflective of the community? |

| Attending policy calls, annual and midyear meetings, and trainings among coalitions (ongoing) | Process and outcome evaluation (qualitative) | Discussion of current coalition activities, including strategies, challenges, and successes. Discussion of current proposed policies related to environmental triggers of asthma; coalition voting on CAFA support or opposition to proposed policies; strategies to garner support or rally opposition among partners and potential partners. |

| Tracking of local, regional, and state policies (ongoing) | Outcome evaluation (quantitative and qualitative) | Outcomes of legislation, regulations, or policies supported or opposed by CAFA network members (in process; enacted; implemented; vetoed; failed). |

The model of change incorporated a quality improvement strategy—UCSF's ongoing assessment, review of the initiative structure and the roles of each participant, and supported opportunities for the communities, technical assistance partners, and funders to refine both overall and site-specific strategies based upon ongoing results.

Selected results focused on technical assistance and midcourse restructuring, policymaker engagement, and policy outcomes related to environmental justice. Additional CAFA evaluation findings were presented elsewhere.32,33

RESULTS

Before the inception of CAFA, the “asthma network” in California consisted of a few local and regional organizations and a loosely connected network of the ALA. The state legislature and the Department of Health Services also conducted some activities related to asthma. In general, the focus of all of these stakeholders was primarily clinical management. Subsequently, CAFA's local coalitions and the statewide network accomplished significant changes as a result of their shift to the implementation of environmental justice policies.

Coalition Maturity

To aid in the evaluation process, UCSF categorized the coalitions into 3 levels of maturity and analyzed results through the framework. Mature coalitions (1996–1999) were active before CAFA was established, and thus had years of experience of working with asthma and other community health issues. Middle coalitions (2000–2001) were more clinically oriented coalitions and active before CAFA, but not to the extent, or with the level of experience, of older coalitions. Young coalitions (2002 or later) consisted of grantees whose work only began with the CAFA initiative and focused on developing an internal structure and capacity.

The extent to which each coalition was able to build structure and capacity depended, in part, on the history of the coalition members, the community, and the technical assistance sought and received. Mature coalitions had well-developed networks and had, or quickly developed, experience with community-based, environmentally focused strategies. Middle coalitions faced challenges in their organizational development, leadership, and/or the community environment in which they were working, and varied widely in their capacities and activities. Younger coalitions also varied in capacity, and in their members’ experience and expertise in the field of asthma. Interestingly, although the coalitions started at different historical points in time, younger coalitions were able to learn quickly from established ones; they were up to speed in a shorter period of time and became effective in their own settings.

Technical assistance and midcourse restructuring.

Technical assistance providers assisted coalitions in building internal capacity by helping them understand the precautionary principle and environmental risks to children with asthma, assess local and state level environmental inequities, use data to support a policy position, provide testimony or evidence, develop grant writing skills and outreach strategies, and learn the various policy forums and procedures at the local, regional, and state levels.

To support external capacity, RAMP, the statewide office, and other technical assistance providers helped coalitions identify potential allies and champions to support their efforts. Technical assistance experts trained coalitions on how to educate policymakers and community members and how to work with the media to frame the portrayal of childhood asthma and mobilize support for environmental justice. RAMP also assisted in identifying state level policy opportunities and worked with local coalitions to prioritize these opportunities and develop relationships with environmental justice organizations.

Through local, regional, and statewide meetings among coalitions, technical assistance partners facilitated sharing of best practices and successful strategies and, where applicable, the development of statewide strategies to integrate individual coalition efforts, thus creating greater levers for statewide change. Coalitions also sought opportunities to connect with external organizations doing similar work, such as New York City's asthma reduction activities.

Three years into the initiative, the foundation and the technical assistance partners assessed the structure of the initiative and designed a midcourse correction to streamline the network. Both governance and technical assistance were redesigned to reduce the number of organizations coordinating and providing support to the coalitions. Figure 1 shows the regional coalitions that were eliminated. This reflected developmental stages of coalition evolution, as well as a new commitment by TCE to focus more directly on policy outcomes.

As a result, coalitions that previously had provided general environmental education to communities and policymakers now focused on linking their work to evidenced-based policy implementation.

Policymaker engagement.

Repeated interviews conducted with local and state policymakers indicated that coalition efforts increased their understanding of environmental issues and of the connections between environmental policy and childhood asthma prevention.

In 2010, about half of policymakers (10 of 22) worked with their local asthma coalition. More than half (12 of 22) reported that coalition activities (e.g., conducting legislative briefings) were influential in the policy process. Over three quarters (17 of 22) considered themselves familiar with the environmental triggers of asthma and reported an increase in knowledge over the last 3 years because of the coalitions’ efforts.

Policy outcomes.

Table 3 presents selected policy outcomes across the 3 CAFA focus areas: housing, schools, and outdoor air quality. Large policy changes included state or local level legislation or changes in regulations, whereas small changes included procedural or practice level changes, such as school district procedures to improve building maintenance for better indoor air quality or the inclusion of residents in local decision-making protocols. Work on housing issues affected primarily local level regulation, whereas work on schools and outdoor air quality involved local, regional, state, and occasionally national policy. The coalitions worked across multiple sectors (community residents, families, schools, organizations, local and regional government agencies, and statewide agencies), and in concert with each other in these efforts.

TABLE 3.

Selected Environmental Justice Policy Results by Topic, 2003–2010

| Legislation, Regulation, or Policy | Primary Allies or Opponents | Achieved or Proposed Environmental Justice Outcomes |

| Housing | ||

| Regulation and precedent-setting law suits to remediate slum housing: reduce vermin; reduce water leaks. Implemented 2008. | Asthma coalition and partners City attorney's office Residents Statewide association of local volunteer housing inspectors | Improves standards for landlords of low-income housing. Reduces asthma risk factors for low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. |

| Coordination across housing inspectors statewide to reduce environmental asthma risk factors. In process since 2007. | ||

| Schools | ||

| Prohibit schools from being built within 500 ft of a freeway, unless pollution is mitigated or there are no other options for siting. Enacted 2003. | Schools Residents Asthma coalitions Environmental scientists | Reduces emission exposures for school-aged children in communities near freeways, primarily low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. |

| Increase awareness of air quality status and safe levels of activity for individuals with asthma, via expansion of school “asthma flags” programs, Implemented at over 130 campuses, 2004. | School administrators Teachers Asthma coalitions | Educates teachers, students, and school personnel about air quality. Enables teachers to modify activity programs for vulnerable students on high pollution days. |

| Strengthen legislation prohibiting siting schools near freeways. Vetoed 2004. | Environmental scientists Community activists Environmental justice organizations | Would have reduced exposure to diesel exhaust for school-aged children, primarily in low-income communities. |

| Establish funding for school facility repairs. Enacted 2006. | Asthma coalitions School districts | Enables repair of ventilation systems and water leaks. Reduces asthma risk factors. |

| School district level procedures to reduce environmental asthma triggers (Solano County). Implemented 2008. | Teachers Union representatives Custodial workers | Improves ventilation; reduces moisture, pet dander, and food exposures in classrooms. |

| Require environmentally sensitive cleaning materials and products in schools. Vetoed 2008. | Green Schools Alliance Asthma coalitions | Would have reduced toxic cleaning products in schools. |

| Strengthen laws to prevent school construction close to freeways. Vetoed 2008. | Construction industry Some school districts | Would have reduced pollution near schools. |

| Prohibit freeway expansion within one quarter mile of school boundaries. Vetoed 2008. | ||

| Improve indoor air quality in schools. Failed 2010. | Asthma coalitions | Would have reduced indoor air pollution in schools. |

| Outdoor Air Quality | ||

| State law regulates idling time for school buses near schools and diesel trucks near ports. Enacted 2004. | Schools Residents Environmental justice organizations Asthma coalitions Environmental scientists Residents Asthma coalitions Asthma coalitions Environmental scientists | Reduces diesel emissions from school busses and idling trucks near ports. Ports tend to be located in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. |

| Replace diesel school buses with cleaner burning models. Enacted 2004. | Reduces student exposure to diesel exhaust pollution. | |

| Remove exemption of farm equipment from pollution regulation. Enacted 2004. | Reduced diesel exposures in agricultural areas and the Central Valley, which has high asthma prevalence among low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. | |

| Set pollution standards for Los Angeles and Long Beach ports. Vetoed 2005. | Would have set pollution standards for the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports, reducing toxics exposures in nearby low-income communities. | |

| Set standards for greenhouse gases in State to reduce global warming. Enacted 2006. | Asthma coalitions Environmental justice organizations Environmental scientists Environmental lobbyists | Regulates greenhouse gasses produced in the State. Encourages green industries by regulating greenhouse gasses. Could reduce toxics in communities. |

| This law was unsuccessfully challenged on the 2010 California ballot. | ||

| Establish pesticide buffer zones near schools. Vetoed 2006. | Low-income neighborhoods Communities of color Environmental justice organizations Asthma coalitions Environmental scientists | Would have reduced exposures of school-aged children to pesticides. Would have primarily affected low-income neighborhoods and communities of color in the Central Valley. |

| Establish user fees for containers in ports. Vetoed 2006. | Low-income neighborhoods Communities of color Environmental justice organizations Asthma coalitions Environmental scientists Physicians for Social Responsibility | Would have funded reductions in port pollution through container fees. Would have reduced toxics in port communities. |

| Propose changes to Central Valley Air District Board membership. Vetoed 2006. | Agribusiness Industry | Would have increased community and scientific membership on regulatory Board. |

| Establish community and scientific membership on Central Valley Air District Board. Enacted, 2007. | Low-income neighborhoods Communities of color Asthma coalitions Environmental justice organizations Environmental scientists | Creates membership for residents and scientists on Regulatory Board. |

| Require for assessment of land use and transportation planning related to pollution, Vetoed 2007. | Low-income neighborhoods and communities are most severely affected by freight movement and the location of freeways. | |

| Federal ruling upholds California's authority to establish greenhouse gas emission standards for vehicles. Implemented 2007. | National and state environmental advocates Communities Auto industry Auto manufacturers | Enables State to set vehicle pollution standards that are higher than national standards. Reduces toxics in State. |

| Establish container fees at ports in Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Oakland. Vetoed 2008. | Low-income neighborhoods Communities of color Asthma coalitions Environmental scientists Environmental justice organizations | Would have reduced port-related pollution. |

| Local Control of Pesticide Regulation. Vetoed 2008. | Agribusiness | Would have reduced toxics from pesticides. |

| Railyards Emission Regulation. Vetoed 2008. | Industry coalitions | Would have reduced toxics near railyards. |

| Create buffer zones between schools and health care facilities and aerial pesticide spraying. Failed 2009. | Agribusiness | Would have reduced toxics from pesticides. |

| Funding for increased regulation of air quality in trade corridors. Enacted 2009. | Low-income neighborhoods Communities of color Environmental justice organizations Asthma coalitions Environmental scientists | Reduces pollution for low-income and communities of color. |

| Air Resources Board to negotiate agreements with 4 railyards to limit diesel emissions. Pending 2010. | Reduces pollution near railyards. | |

| Pollution fines adjusted for inflation. Enacted 2010. | Reduces pollution. | |

Note. Because this initiative strongly focused on environmental policy and advocacy, training and technical assistance was provided by the foundation on advocacy, which was funded in compliance with foundation rules or supported by non-foundation resources if the activities involved lobbying.

Coalition activities to reduce asthma triggers in substandard housing focused on improving regulation to reduce rats and cockroaches, fix water leaks and resulting damage, and address other indoor environmental hazards. Coalition allies in these efforts included residents, the city attorney's office, and the association of local housing inspectors. Coalition efforts led to improved standards for landlords of low-income housing in Los Angeles.

Coalition efforts in the area of schools focused primarily on policies and procedures to decrease nearby outdoor air pollution and reduce exposures to chemical cleaning products and pesticides. Allies for these endeavors included residents, environmental scientists, environmental justice organizations, and school personnel. One of the most difficult challenges was the attempt to strengthen prohibitions against new school construction within 500 feet of freeways, which were major sources of outdoor air pollution.

Significant advocacy activities in outdoor air quality included seeking reductions of diesel and other pollutants near schools, ports, freeways, railyards, and agricultural areas. For example, diesel emissions from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, which were located near low-income neighborhoods and communities of color, constituted 20% of the diesel toxics in California.34

DISCUSSION

The CAFA initiative succeeded in moving the coalitions’ efforts “upstream” to address environmental inequities–from an earlier focus on changing individual and clinic-focused diagnosis, treatment, and management—to a focus on environmental prevention through policy change. By engaging and connecting trusted community-based organizations that provided asthma education and treatment, the initiative built on existing activities and integrated these efforts to guide policy at the local, regional, and state levels, a strategy that became known as a “grassroots to treetops” approach. In building the capacity of individual coalitions and, by extension, their communities, and in fusing these efforts across the state, the initiative created a powerful, united network for environmental policy advocacy.

In comparing the success of policy change efforts across coalitions, the following contributed to successful coalitions.

Community involvement: Coalitions that had a strong community base before the initiative built upon their existing knowledge and networks and moved into environmental justice policy advocacy more quickly than coalitions that lacked strong community ties. Organizations with salaried staff members from the community made more progress in expanding relationships and establishing policies than organizations with volunteer staff.

Meeting communities on their level: Coalitions discovered that they needed to build upon community experience and knowledge to be successful in their work. By meeting communities “where they were,” coalitions worked toward policy goals that more closely reflected residents’ needs, resources, and desires. By allowing the community to prioritize the direction of advocacy efforts, the coalitions achieved policy change through increased community involvement and support. This ranking of priorities occurred within the framework of the initiative, which included a focus on asthma, environmental risk factors, and policy.

Learning environment: Contact with others engaged in policy advocacy in housing, schools, and outdoor air quality provided additional perspectives to the coalitions. This “peer learning environment” allowed each coalition to develop as needed and at its own pace. Younger coalitions benefited directly from more mature groups’ knowledge and history, whereas older coalitions were able to expand their work and move further upstream.

Training in policy advocacy: Extensive training and ongoing technical assistance in the areas of policy, communications, and marketing were necessary for coalitions to gain an in-depth understanding of policy advocacy, including what the work entailed, how to conduct it, and appropriate strategies. Technical experts worked closely with coalitions throughout the initiative to ensure understanding and integration of these concepts.

Incorporating environmental science and data into community training: Coalitions found greater success in their efforts when they worked closely with experts in environmental science and environmental justice advocates, who provided sound scientific data, engaged in discussions about policy approaches and strategies, and assisted in crafting testimony to policymakers. Some residents became environmental experts in their communities, furthering the policy advocacy efforts of the initiative.

Use of data and media: Coalitions that learned how to use data and media to educate, raise awareness, and promote policy change in their communities increased their impact. Some developed multistep media strategies to introduce and frame issues, define necessary next steps, and obtain support from stakeholders. When successful, these strategies allowed coalitions to make a stronger case for their policy priorities. When multiple stages of activity were needed to enact environmental justice policies, these strategies provided a mechanism to continue the education and advocacy of stakeholders. Integrating community members into these activities empowered the individuals involved, as well as the coalition.

Sustainability of the local coalitions: To achieve sustainable environmental policy outcomes at the local, regional, and state levels, coalitions identified champions to further the initiative's policy goals, strengthen its networks, and obtain new sources of funding to support future work.

Thus, community involvement, foundation support, and technical expertise were essential to success in achieving local and state policy change. Building and expanding the coalitions’ work required democratic decision-making processes and community member participation at each stage.35,36 The ongoing funding, dedication, and close attention of foundation project officers ensured timely, thoughtful problem solving. The broad array of specialists from environmental science, policy analysis, asthma prevention, media and communication, and evaluation significantly improved the coalitions’ ability to reach their intended audiences and create policy change.

Some argued that it was unreasonable to expect community coalitions to address policy issues within the first several years of their existence.37 CAFA proved this untrue. The initiative developed and implemented policy within 2 years because of the quality and depth of the technical knowledge, training, and support provided by the technical assistance partners. With midcourse streamlining of the initiative's structure, the network functioned more smoothly and efficiently, allowing for better integration across all coalitions and partners. Through the process of collaborative development, the coalitions learned to work with each other and with their communities, expanded their technical expertise, assessed policy options, and made significant impact.

Not all of the coalitions’ efforts led to concrete outcomes or improvements in a timely manner. Much of the work of policy advocacy—including developing relationships with individuals and organizations, navigating various policy spheres, and mobilizing residents and stakeholders around a particular piece of legislation—were long-term activities.

A number of policies were proposed multiple times before they were ultimately passed and implemented. In particular, policy implementation related to “structural interests,” such as ports, freeway locations, and school siting, required prolonged policy engagement by communities, environmental experts, and coalitions. It might be several more years before some of the coalitions’ efforts come to fruition.

Other challenges and strategies for overcoming them included dealing with outside groups and bureaucracies. It was often difficult to convince governments and other organizations to “fit” environmental justice issues into their list of priorities. Finding supportive and appropriate partners, whether individuals or organizations, was often a challenge. Trying to hold meetings with unresponsive groups, working with unsupportive personnel at some agencies, or competing with other priorities, timelines, and budgets was discouraging for coalition members. Engaging with individuals or entities in a bureaucratic setting, such as local school districts or city government agencies, created substantial obstacles to policy efforts. In response, coalitions spent considerable energy networking with allies and potential partners, building relationships, and developing joint projects for collaboration. Once an interested ally was found, coalition members worked to nurture and maintain their interest, building champions to further their work. By building strong networks with others, many coalitions developed reputations in their communities as authorities in environmental science or policy advocacy, which assisted them in gaining further support or partners.

There were challenges to capturing the effects and outcomes of policy advocacy efforts. These activities could take years before the concrete effects of advocacy could be documented. By focusing on specific policy outcomes, channeling energy into data collection and dissemination, and employing champions and media to further their cause at all geographic levels, coalitions began the significant process of policy and systems change.

Limitations

There were some limitations to this study. Many of the results presented came directly from grantees and technical assistance partners. Relying on self-reported progress and outcomes among coalitions had its drawbacks, in that organizations might have presented only their successful efforts. Measuring the effectiveness of coalition activities was also difficult, because it was hard to attribute policy successes or community or decision-maker support to a collaborative's efforts. Because the social, fiscal, and political climates often encompassed many factors that contributed to success, it was challenging to measure exactly what did, and did not, contribute to policy changes.

As with all initiatives to promote environmental justice, the findings from this study might be unique, and therefore difficult to replicate, or generalize to other communities. Although certain strategies led to progress and success, the same approach might not be successful, or as successful, in a different community setting. However, coalition capacity building, tailored technical assistance, and sustained foundation funding aimed at policy change all played major roles in this initiative and would likely be translatable to other settings.

Conclusions

Findings from the CAFA initiative supported the value of including an environmental justice approach in policy advocacy efforts to reduce health inequities. The provision of strong technical assistance, the incorporation of community involvement, and the implementation of multilevel strategies to shape policies at the local, regional, and state levels all contributed to reducing environmental inequities that led to childhood asthma. Integrating knowledge from the fields of sociology, economics, and urban and regional planning; improving understanding of the dynamics of environmental inequities; and developing additional strategies for communities to build social capital all made contributions to this initiative. Incorporating an environmental justice approach to develop policies that responded to inequities based on race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geography was a useful strategy to address persistent health inequities, and warrants further application and study.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from The California Endowment. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions and participation of all of the CAFA grantees, technical assistance partners, and collaborating organizations and individuals who were critical to the success of this initiative.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the University of California San Francisco institutional review board, approval number H5352-33786-01.

References

- 1.Morello-Frosch R, Pastor M, Porras C, Sadd J. Environmental justice and regional inequality in Southern California: implications for future research. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(suppl 2):149–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landrigan PJ, Rauh VA, Galvez MP. Environmental justice and the health of children. Mt Sinai J Med. 2010;77:178–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez L, Künzli N, Avol E, et al. Global goods movement and the local burden of childhood asthma in southern California. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(suppl 3):S622–S628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pastor M, Jr, Sadd JL, Morello-Frosch R. Waiting to inhale: the demographics of toxic air release facilities in 21st-century California. Soc Sci Q. 2004;85(2):420–440 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meng Y-Y, Rull RP, Wilhelhm M, et al. Outdoor air pollution and uncontrolled asthma in the San Joaquin Valley, California. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:142–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarpong SB, Hamilton RG, Eggleston PA, Adkinson NF. Socioeconomic status and race as risk factors for cockroach allergen exposure and sensitization in children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;97(6):1393–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanphear BP, Aligne A, Aungier P, et al. Residential exposures associated with asthma in US children. Pediatrics. 2001;107(3):505–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hood E. Dwelling disparities: how poor housing leads to poor health. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(5):A310–A317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bashir SA. Home is where the harm is: inadequate housing as a public health crisis. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):733–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolstein J, Meng Y, Babey S. Income disparities in asthma burden and care in California. The UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, December 2010. Available at: http://www.healthpolicy.ucla.edu/pubs/files/asthma-burden-report-1210.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canino G, Koinis-Mitchell D, Ortega AN, et al. Asthma disparities in the prevalence, morbidity, and treatment of latino children. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2926–2937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDaniel M, Paxson C, Waldfogel J. Racial disparities in childhood asthma in the United States: evidence from the National Health Interview Survey, 1997-2003. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):e868–e877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, California Department of Public Health 2007 California health interview survey: ask CHIS. Available at: http://www.chis.ucla.edu. Accessed December 2010

- 14.Mendez-Luck CA, Yu H, Meng YY, et al. Estimating health conditions for small areas: asthma symptom prevalence for state legislative districts. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:(6, Pt 2):2389–2409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz NA, Pepper D. Childhood asthma, air quality, and social suffering among Mexican Americans in California's San Joaquin Valley: “nobody talks to us here.” Med Anthropol. 2009;28(4):336–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claudio L, Stingone JA, Godbold J. Prevalence of childhood asthma in urban communities: the impact of ethnicity and income. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:332–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearlman DN. Neighborhood-level risk and resilience factors: an emerging issue in childhood asthma epidemiology. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2009;5(6):633–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aligne CA, Auinger P, Byrd RS, Weitzman M. Risk factors for pediatric asthma: contributions of poverty, race, and urban residence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:873–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canino G, McQuaid EL, Rand CS. Addressing asthma health disparities: a multilevel challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1209–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frumkin H, Frank L, Jackson R. Urban Sprawl and Public Health: Designing, Planning, and Building for Healthier Communities. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pastor M, Dreier P, Grigsby JE, Lopez-Garcia M. Regions That Work: How Cities and Suburbs Can Grow Together. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pastor M, Benner C, Matsuoka M. This Could Be the Start of Something Big: How Social Movements for Regional Equity Are Reshaping Metropolitan America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams DR, Sternthal M, Wright RJ. Social determinants: taking the social context of asthma seriously. Pediatrics. 2009;123:S174–S184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs DE, Kelly T, Sobolewski J. Linking public health, housing, and indoor environmental policy: successes and challenges at local and federal agencies in the United States. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(6):976–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright RJ, Suglia SF, Levy J, et al. Transdisciplinary research strategies for understanding socially patterned disease: the Asthma Coalition on Community, Environment, and Social Stress (ACCESS) project as a case study. Cien Saude Colet. 2008;13(6):1729–1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy JI, Brugge D, Peters JL, et al. A community-based participatory research study of multifaceted in-home environmental interventions for pediatric asthmatics in public housing. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2191–2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vásquez VB, Minkler M, Shepard P. Promoting environmental health policy through community based participatory research: a case study from Harlem, New York. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):101–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brindis CD, Wunsch B. Finding Common Ground: Developing Linkages Between School-Linked/School-Based Health Programs and Managed Care Health Plans. Sacramento, CA: The Foundation Consortium for School-Linked Services; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lafferty CK, Mahoney CA. A framework for evaluating comprehensive community initiatives. Health Promot Pract. 2003;4(1):31–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altman DG. Sustaining interventions in community systems: on the relationships between researchers and communities. Health Psychol. 1995;14:526–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreger M, Brindis C, Arons A, Sargent K. Turning the ship: moving from clinical treatment to environmental prevention: a health disparities policy advocacy initiative. Foundation Rev. 2009;1(3):26–42 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kreger M, Brindis CD, Manuel DM, Sassoubre L. Lessons learned in systems change initiatives: benchmarks and indicators. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39(3–4):301–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hricko A. Global trade comes home: community impacts of the goods movement. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(2):A78–A81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark NM, Doctor LJ, Friedman AR, et al. Community coalitions to control chronic disease: allies against asthma as a model and case study. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(2, Supplement):14S–22S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole LW, Foster S. From the Ground Up. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kreuter MW, Lezin NA, Kreuter MW, Green LW. Community Health Promotion Ideas That Work. 2nd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2003 [Google Scholar]