Abstract

Chronic disease is the leading cause of death in the United States. Risk factors and work conditions can be addressed through health promotion aimed at improving individual health behaviors; health protection, including occupational safety and health interventions; and efforts to support the work–family interface. Responding to the need to address chronic disease at worksites, the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention convened a workshop to identify research priorities to advance knowledge and implementation of effective strategies to reduce chronic disease risk. Workshop participants outlined a conceptual framework and corresponding research agenda to address chronic disease prevention by integrating health promotion and health protection in the workplace.

Approximately half of Americans live with a chronic disease, and about one fourth report residual effects from it.1 Chronic diseases, including heart disease, cancer, and stroke, are the leading cause of death in the United States.2 Disparities in chronic disease occur by race and ethnicity and by socioeconomic status, with minorities and lower income groups having a higher prevalence of heart disease, cancer, and stroke and multiple risk factors for these conditions.3–5 Of additional concern is that the prevalence of chronic disease is higher in the United States than in other developed countries.6–8 More than 81 million Americans have cardiovascular disease, at an estimated cost of $503 billion in 2010.9 In 2005, more than 1.3 million people were diagnosed with cancer, with costs in 2007 estimated at $219 billion.10 Almost 24 million people have diabetes, at a cost of $174 billion in 2007.11 Approximately 67% of adults are overweight or obese,12 with a projected cost of $147 billion for 2008.13 In addition, nonfatal chronic conditions, such as musculoskeletal disorders14 and psychological disorders,15 are major sources of disability.16

Worksites provide a venue to address multiple individual risk factors and risk conditions through worksite health promotion aimed at changes in individual behaviors, worksite health protection including occupational safety and health interventions, and efforts to address unhealthy work-family conflict.17,18 As a venue for delivering chronic disease prevention efforts, worksites provide a ready channel for reaching the large segment of the population that is employed. Worksite conditions also contribute to the development of chronic diseases, for example, through hazardous job exposures, high job demands, and inflexible work schedules.

Individual health behaviors contribute significantly to chronic disease outcomes. In 2000, 435 000 deaths (18.1% of total deaths) were attributed to tobacco use, 365 000 deaths (15.2%) were attributed to a combination of poor diet and lack of physical activity, and 84 000 deaths (3.5%) were related to misuse of alcohol.19,20 These 4 individual health behaviors collectively accounted for approximately 40% of all deaths in the United States in 2000.21 Worksite health promotion is an effective way to enhance health-promoting behaviors, reach a large segment of the population, and reduce chronic disease risk factors. Comprehensive worksite health promotion has been recommended by the American Heart Association, the American Cancer Society, Healthy People 2010, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the National Institutes of Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).22–25

In 2006, US health care spending was reported to be more than $2 trillion,26 and employers on average paid more than one third of this cost.27 A meta-analysis of the literature on costs and savings associated with worksite health promotion programs indicated that medical cost reductions of about $3.27 are observed for every dollar invested in these programs.28 This figure has been corroborated by recent systematic reviews and economic analysis conducted by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services, which reported an annual savings of $3.20 for every dollar invested.29,30 Other benefits of worksite health promotion include reduced absenteeism28,30 and improved employee attitudes toward work.31

The work environment, encompassing the physical, psychosocial, and organizational environments, directly shapes employee health, safety, and health behaviors.22 In 2008, more than 5000 workers died from occupational injuries,32 and work-related illnesses account for 49 000 deaths annually.33 More than 4.6 million workers experienced nonfatal occupational injuries or illnesses in 2008, about half of which resulted in time away from work because of recuperation, job transfer, or job restriction.34 Employers and insurers spent approximately $85 million in workers’ compensation costs in 2007,35 although this figure is only a portion of the costs associated with work-related illness and injury that are borne by employers, workers, and society overall. In 1992, the total economic costs to the United States from occupational illnesses and acute injuries was estimated to be between $155 billion36 and $171 billion,37 figures that are similar to those for all cancer or all cardiovascular disease in this time period.36,38

Worksite health protection initiatives include efforts to improve occupational safety and health, address organizational factors at work that influence worker health, and support work–life balance. Compliance with safety and health standards was mandated by the passage of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970. Occupational Safety and Health Act rules, such as those pertaining to cotton dust, inorganic lead, and blood-borne pathogens, have resulted in reduced exposures and illnesses.39 Efforts by government, labor, management, and health professionals have also led to reductions in exposure to biomechanical risk factors at work that contribute to work-related musculoskeletal disorders, the most common category of occupational disease reported to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.14 Labor–management health and safety committees and workers’ compensation insurers have reported that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration's support of prevention through regulation and training have contributed to the prevention of work-related injuries and illnesses.40 Worksite initiatives can possibly redress sources of stress at work, including inflexible work schedules, low job control, and excessive job demands,41,42 that lead to negative health outcomes for employees and their families.

Integrating health behavior change programs with work environment changes may be synergistic and enhance their effectiveness.22,43 Beyond using the worksite as a platform to promote changes in individual health behaviors, such as smoking, dietary intake, physical activity, and weight control, a more integrated approach recognizes that the workplace acts as both an accelerator and a preventer of chronic disease and is a key determinant of individual health behaviors through physical, social, organizational and psychosocial mechanisms. Simply stated, workers may perceive changes in their individual health behaviors to be futile in the face of significant occupational exposures that have considerable bearing on their health. Conversely, management and labor efforts to create a healthy work environment may contribute to workers’ motivations to modify their personal health behaviors, and they may foster a climate of trust that supports workers’ receptivity to their employer's messages regarding individual health behavior change.44–46 This principle of integrating worksite health protection with worksite health promotion was recently endorsed by the American Heart Association for cardiovascular health promotion.47

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health; the CDC; the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development; and the National Cancer Institute convened a workshop to identify research needed to develop effective programs to reduce chronic disease risk and to support worker and family health by effectively promoting healthy and safe individual behaviors; reducing physical, psychosocial, and organizational risks at the worksite; and promoting work–life balance. The workshop, held May 21 and 22, 2009, was cochaired by Barbara Israel, professor of health behavior and health education in the School of Public Health, University of Michigan, and Glorian Sorensen, professor of society, human development and health at the Harvard School of Public Health. The panel, selected by the workshop sponsors to reflect a range of perspectives on chronic disease prevention in the workplace, consisted of specialists in epidemiology, sociology, occupational and preventive medicine, organizational psychology, occupational health psychology, health education and health behavior, environmental and occupational health, economics, exercise physiology, ergonomics, pediatrics, and human development. Their interests were varied and included individual behavior and organizational change research, family and community health research, public policy, intervention design and evaluation, translation and outcomes research, participatory action research, and health disparities (roster available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.).

The workshop objective was to develop a comprehensive and coordinated research plan to build the evidence base for effective chronic disease prevention for working adults and their families through worksite interventions. To achieve this objective, the workshop had 3 main informational sessions: promoting individual behavior change, changing the work environment (physical, psychosocial, and organizational), and intervening to influence the work–family community interface. Each session was guided by 8 areas of discussion: research strategy, current state of the science, conceptual models, research design, practices and policies, cost-effectiveness, barriers, and specific populations. We present 3 parallel worksite approaches to preventing chronic disease—promoting individual behavior change, changing the work environment, and addressing work–family community interface—and explore opportunities for coordination and integration of these approaches.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

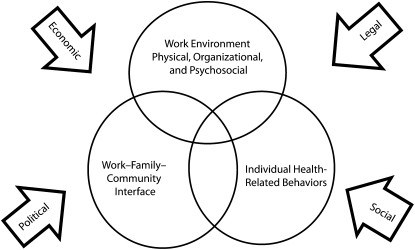

The workshop discussions were guided by a conceptual framework (Figure 1). The 3 intervention targets that were the workshop's focus are individual health behaviors, the work environment, and impacts on the work, family, and community interface. A focus on individual health behaviors, such as smoking, dietary patterns, physical activity, and weight control, may occur by itself or as part of a multiple risk-factor approach, and the workplace is typically used as a platform for program delivery; changes in the work environment may be implemented to support health behavior changes. Components of the work environment that may influence worker and family health include worksite culture; organizational policies and practices; hazardous chemical, physical, and biological exposures; psychological job demands; job control; work schedule and control over work time; work-related rewards; organizational justice; work norms and social support; and union status. Additional attention must be paid to the impact of the interrelated work, family, and broader community systems, given the importance of psychological and behavioral spillover and crossover between work and family lives. The conceptual model also acknowledged the roles of economic, legal, political, and social factors, which may influence worker health, job insecurity, access to health insurance, and worker and family stress.18 Opportunities for collaboration, integration, and synergy occur at the overlap of the 3 intervention targets, thereby strengthening the potential impact of chronic disease prevention in the workplace.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual model illustrating the 3 intervention targets and opportunities for collaboration, integration, and synergy: Workshop on Worksite Chronic Disease Prevention, Bethesda, MD, May 21–22, 2009.

PROMOTING INDIVIDUAL HEALTH BEHAVIOR CHANGE

Workshop participants referred to the Healthy People 2010 objectives for a definition of comprehensive worksite health promotion, which includes several core components: health education programs, a supportive social and physical environment, integrated programs (e.g., budget, staffing, resources), screening (including treatment and follow-up as needed), and links to other assistance programs.25 Worksite health promotion programs also include a needs assessment, individualized health messages, encouragement of self-care, use of incentives, social support, and sufficient duration to enhance implementation and maintenance.48 Through Healthy People 2010, the CDC has recommended that at least 75% of worksites offer a comprehensive worksite health promotion program.49 The most recent National Worksite Health Promotion Survey found, however, that only 7% of worksites do so.50 Although larger worksites are less numerous than smaller ones,51 worksites with 750 or more employees were more than 6 times as likely to offer comprehensive worksite programs than those with 50 to 99 employees.50 Larger worksites also offered more variety in programs such as physical activity, tobacco, fitness and nutrition, and screening services than did smaller worksites.50

Barriers to worksite program implementation include low employee participation, lack of employee interest, limited staff resources, cost, misalignment of incentives among different stakeholders, and insufficient management support.50,52 Workshop participants discussed strategies for increasing employee participation, including peer and management support and incentives, as well as for implementing and maintaining a respectful partnership with stakeholders (e.g., employees and their families, labor, management, health professionals, insurance companies, government agencies).

Physical activity provides a useful example of a health behavior that can be effectively influenced through multilevel worksite health promotion. Only about 32% of US adults have reported engaging in regular leisure-time physical activity, with even lower rates among ethnic minority, low-income, and other underserved populations53; rates are also lower when activity is objectively monitored.54 Several studies have demonstrated the potential impact of brief, socially obligatory structured group exercise breaks on paid time.55–58 Future studies may explore the use of physical activity breaks in increasing participation in physical activity and enhancing sustainability, as well as identifying the organizational benefits of exercise for injury prevention.59–63

Participants discussed the challenge of sustaining health promotion programs after implementation and of the tendency of some programs to devolve from evidence-based models over time. A framework for implementing, sustaining, and evaluating effective programs, such as the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance (RE-AIM) model, can be a helpful guide for program planning and evaluation. The RE-AIM framework addresses both employee and organizational interventions by considering the reach and representativeness of comprehensive worksite health promotion programs, as well as their efficacy, adoption, implementation, and maintenance.64,65

Workshop participants discussed the need for ongoing research to identify characteristics of successful programs, including research using in-depth, mixed-method, and comparative case studies.66 For example, research examining the extent to which worksite health promotion efforts may contribute simultaneously or sequentially to multiple health behavior changes, and the extent to which 1 health behavior change may serve as a gateway to other health behavior changes (e.g., increases in physical activity may spark and support changes in dietary patterns) may be useful. Future research may also test methods of intervention with high-risk employees (e.g., overweight or obese employees) via stepped-care approaches or other methods tailored to diverse populations on the basis of race or ethnicity, age, health status, and other key characteristics. Process evaluation methods may be used to examine program impacts on subpopulations when studies have adequate power for key subgroup analyses. Formative research is needed to understand factors associated with low participation rates among both employees and employers67 and the role of key social influences on employee participation, such as from family members, management and supervisors, and union representatives. Specific research is also needed to identify best practices for health promotion in small businesses.68

Workshop participants stressed the need to identify the level and intensity of intervention exposure needed for optimal efficacy and to differentiate which intervention components contribute the most to behavior changes. This information is also important in determining favorable cost–benefit ratios and returns on investment.69–71 The economic rationale behind health promotion interventions is particularly important because of the need to convince program sponsors to initiate and maintain such programs.72 Future research should consider, for example, the relevance of health promotion programs to employers with fully insured health plans versus self-insured plans and the role of behavioral economics in chronic disease prevention.73–75

PROMOTING CHANGES IN THE WORK ENVIRONMENT

The physical, psychosocial, and organizational work environments are important contributors to chronic disease. Cancer is the leading cause of workplace fatalities worldwide and accounts for about one third of all workplace fatalities.76 The World Health Organization and others have estimated that 8% to 16% of all cancers are caused by preventable exposures to workplace hazards.76,77 Shift work may also lead to increased cancer risk.78 Risk factors for cardiovascular disease include workplace environment factors such as exposure to chemicals, such as carbon monoxide, carbon disulfide, solvents, and lead; organizational factors such as work schedules, including long work hours and shift work; and psychosocial stressors, such as high-demand–low-control work (job strain), high job effort combined with low job rewards (e.g., income, support, respect, and job security), and organizational injustice.15,79 Estimates of the proportion of cardiovascular disease associated with these work-related factors have ranged from 15%80 to 35%.81 Work schedule factors and psychosocial stressors contribute to obesity, smoking, heavy alcohol use, and lack of exercise,82–84 as well as to musculoskeletal disorders85; psychological disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and burnout15; and work–family stress and conflict.86,87 Workplace risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders include repetition, force, awkward postures, vibration, and temperature. Each year, these disorders affect about 1 million workers and cost the United States between $45 billion and $54 billion in compensation expenditures, lost wages, and decreased productivity.14

Risks posed by the work environment do not affect all workers equally. Workshop participants discussed older workers, noting the more than 100% increase in the number of workers aged 65 or older between 1997 and 2007, compared with a 59% increase in total employment during that decade.88 Chronic disease is more prevalent in older workers than in younger workers. Research using the work ability index,89,90 which captures workers’ assessment of their individual ability to be productive in the job given their current health status, has shown that older workers consistently score lower on work ability than younger workers. Although average work ability decreases with age, factors such as improvements in ergonomics, reductions in work stress and work demands, improved supervisor support, flexible work schedules, teamwork, individual lifestyle health promotion (e.g., physical activity), and building workers’ skills and competencies can improve the work ability index.91 Both chronic musculoskeletal disease and low work ability are highly predictive of disability.92–94 Participants discussed the utility of the work ability concept and other measures to capture an important interplay between health status and efforts to change health and work. Workplace interventions that integrate improved workplace safety and health conditions with personal health promotion or individual interventions may be effective in preserving work ability, reducing disability, and preventing or helping people to manage chronic illnesses as they age.56,95

Risks posed by the work environment also vary by employee socioeconomic position, as illustrated by the differential impacts of work stressors, and their relationship to health behaviors and chronic diseases.96 Work stressors associated with chronic disease include work organizational practices and characteristics (e.g., downsizing, restructuring, privatization of public services); production characteristics (e.g., piece-rate incentive pay systems, electronic surveillance, inadequate staffing); task-level psychosocial stressors (e.g., job strain, low job control, long hours, shift work); and other work-related factors (e.g., organizational injustice, job insecurity, safety and health hazards).97,98 Workshop participants noted the evidence that socioeconomic position and work stressors interact. For example, blue-collar workers experiencing job strain are more likely than white-collar workers experiencing job strain to have heart attacks (among Swedish men)99 and elevated blood pressure (among New York City men).100 The workgroup discussed the growing socioeconomic disparities in cardiovascular disease101 and its risk factors, with risk increasing for lower status (blue-collar) workers relative to higher status (white-collar) workers.102 Relative to other workers, workers of lower socioeconomic status also face more hazardous physical and psychosocial workplace exposures and have less access to health promotion programs at work.103 Participants suggested that labor market trends and related changes in lower income workers’ working conditions may contribute to disparities in chronic disease. These trends include stagnant real income and growing income inequality, the decreasing proportion of the US labor force in unions, increases in precarious or contingent work, deregulation, and privatization of government services.15,97

Further research is needed to examine the efficacy of interventions promoting changes in the work environment, with attention given to modifying factors such as job type, job status, employment contract, industry, and unionization status. This research should examine the range of mechanisms (e.g., toxicity, psychological stress mechanisms, and biomechanical stress) by which hazardous occupational exposures increase the risk of chronic disease. Improved understanding of strategies to promote healthy aging at work is also needed, as is understanding of work environment factors related to global economic competition that may explain growing socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease and related risk factors.

Tools for assessing worksite support for workers’ health behaviors (e.g., HeartCheck104), as well as health risk appraisals, need to be expanded to include hazardous occupational exposures. Because workers’ compensation systems capture only a small fraction of work-related chronic disease, novel methods, such as access to medical insurance claims databases linked to employment data, are also needed to understand the work relatedness of chronic disease and its various mechanisms.

Whereas these areas for further research are important, integrating research methods into practice and operations can provide significant insight into how to implement solutions that work.105 The applicability and acceptability of checklists, measurement tools, and surveys will vary by industry and sector, as will the resources the workplace has to redress problems. Considering the applicability of research to practice is important in examining use of measurement and evaluation tools that may also serve as interventions.

Research is needed on the impact of legislative and regulatory policy changes at state and national levels on exposures in the work environment, worker health behaviors, and chronic disease risk. For example, tracking the potential impact of health care reform, changes in federal or state laws on minimum staffing levels among nurses, investments in ventilation systems to control chemical exposures, and state or municipal legislation regarding paid family leave or paid sick leave will be important.106 Research should address the organizational and economic factors that predict how fully workplaces implement these policy changes.107

WORKPLACE INTERVENTIONS AND THE WORK–FAMILY–COMMUNITY INTERFACE

Work also influences health through its interface with workers’ families and their communities. Workshop participants discussed the changing nature of work–family dynamics, the resulting impact of workers’ exposure to stressors at home and on the job, the potential effects not only on workers’ health but also on the health of their families, and the implications of workplace interventions to reduce work–family stress.

Attention to the work–family interface has increased over the past 30 years with the increasing number of women working outside of the home, the corresponding increase in dual-earner families, delays in childbirth, and an increasing percentage of workers who are caring for both children and aging parents.108 These sociodemographic changes reduce family time and contribute to work–family stress and broader changes in family members’ roles.109,110 With increases in service sector employment, coupled with increases in technology and the global economy, workers are required to operate in an all-day, all-week work environment. Many workers occupy low-wage, high-demand service jobs, requiring them to have second jobs to make ends meet. Work–family conflict, or the stress and interference of engaging in both work and family roles simultaneously, has been linked to mental health problems such as depressive symptoms and psychological distress, lower self-reported health,111–116 more chronic physical symptoms, and higher sickness absence.117,118 Work–family conflict has also been related to higher work stress, family stress, and substance abuse,86,87,119 as well as to decreased healthy eating behaviors.120 Work–family conflict may also result in decreased organizational commitment and job satisfaction, absenteeism, and increased intentions to leave the job.86

Although workers’ families and communities may clearly support workers through mechanisms such as positive spillover and social support,121 much research in the area of work and family has identified the detrimental effects of integrating multiple roles on worker and family health.86 These detrimental effects have primarily been examined among white-collar workers with greater access to flexible work schedules and control over work hours. Workshop participants speculated that the impact of work–family conflicts and stress may be more pronounced for lower wage workers because of the lack of workplace support and higher levels of psychosocial stressors such as demanding supervisors, long work hours, and unpredictable work schedules.

Formal workplace supports, benefits, and policies that are aimed at reducing such work–family conflict include providing dependent care support via subsidies, resources, and referral; alternative work schedules; and increased worker control over when, where, and how work is performed. Informal support comes from organizational and management culture. Research has demonstrated that the success of formal supports in affecting worker and family health and well-being is dependent on the level of organizational and managerial informal support for work and family.122 Furthermore, a recent quasi-experimental study of grocery workers and their supervisors found beneficial effects of supervisory training and a self-monitoring intervention to improve supervisor support for work and family on worker job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and self-reported physical health symptoms.123

Although substantial research has indicated that the psychosocial characteristics of the work environment, such as supervisor support, work role demands, and control over work time, spill over to affect workers’ health, evidence has also shown that the work environment can affect workers’ family members. This crossover—the transmission of stress and strain from one individual to another—occurs between workers and their family members.41,42 When considering chronic disease prevention in the workplace, workshop participants recommended using a systems perspective in studying the effects of workplace prevention programs on the family and on workers and evaluating the impact of family characteristics on how workers respond to such interventions at work.108 Workplace interventions addressing workers, their family members, and the community are needed to prevent or diminish adverse work–family conflict and crossover effects.

Much of what is known about workplace supports, benefits, and policies aimed at reducing work–family conflict has been based on anecdotal or cross-sectional evidence. The lack of longitudinal research, experimental and quasi-experimental designs, and nonrepresentative samples has limited the ability to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of work- and family-specific policies or initiatives.124 Workshop participants discussed the impact of formal and informal work–family supports on workers’ ability to integrate work and family. Research is needed regarding factors that contribute to the adoption, implementation, and use of formal work–family policies. An understanding of the impact of working conditions, such as type of work schedule and high-demand, low-control work, on working families and their multiple demands would be beneficial, as would a better understanding of the relationships between community supports and work–family conflicts (e.g., the impact of programs such as Head Start on work–family stress among low-wage families and the effects of paid family and medical leave on workers’ health outcomes). Formal workplace and federal policies that affect workers and their ability to manage work and family should be examined in light of their ultimate impacts on worker and family health.

Increasing the understanding of the informal workplace culture, its impact on supporting or hindering worker health and well-being, and ways in which to intervene to support its positive effects is also important. Future research agendas should pursue factors that contribute to such informal support, such as workplace characteristics, individual characteristics, and the broader economic, legal, political, and social environments.

Currently, work–family policies and benefits are unequally distributed, with workplaces with more professional workers being more likely to provide these supports. Unequal access within a workplace often occurs, with workers in higher status occupations being more likely than other workers to have flexible schedules and eligibility for benefits.125–127 Future research should address whether broadening access to these work–family supports improves the health and well-being of lower status, lower wage, and older workers and their families and whether new interventions are needed to address these workers’ needs.

FINDING SYNERGY ACROSS DISCIPLINARY PERSPECTIVES

The workshop explored not only the parallel paths of these 3 approaches to worker health but also the potential avenues for synergy, coordination, and integration as a means of strengthening chronic disease prevention efforts in the workplace, which scientific evidence has increasingly supported.22,43-46,128 This approach attends to individual health behaviors and to the work organization and environment, including hazardous exposures, work stressors, and organizational policies and practices, as well as work–family demands.18,129 Research has demonstrated that blue-collar workers are more likely to make health behavior changes, such as quitting smoking, when worksite health promotion programs are coupled with workplace hazard assessments and changes in the work environment.128,130,131 Researchers are also exploring the links between physical and psychosocial work conditions and a range of musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and mental health outcomes.43,132

National initiatives for further research in this area are now underway. The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health WorkLife Initiative is a broad-based effort aimed at sustaining and improving worker health through worksite programs, policies, and practices that promote and protect worker health at the organizational and individual levels.133 The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health has identified core essential elements of effective workplace programs and policies for improving worker health and well-being.134 The Work, Family, and Health Network, funded jointly by the CDC and the National Institutes of Health, is another example of a worker health research initiative; the network is aimed at developing and evaluating the effects of worksite work–family policies and practices that affect the health of workers and their families.135

Workshop participants discussed challenges to the development of a shared research agenda aimed at reducing risk of chronic disease among workers and their families. Convening multidisciplinary teams as a foundation for a transdisciplinary approach requires surmounting barriers between scientific disciplines, including developing pooled bodies of knowledge based on shared language and jointly developed methods.136,137 These diverse disciplinary perspectives rely on communications through different journals and professional meetings and on funding mechanisms that cut across the National Institutes of Health and the CDC. The diverse backgrounds cutting across the field contribute to differing perspectives on worker health. For example, the premise that worker health begins with individual behavior change set in motion intervention strategies different from the legal formulation in the Occupational Safety and Health Act, which begins with the assumption that management bears primary responsibility for worker health and safety on the job. Overcoming the segmentation of these fields will ultimately require an inclusive, comprehensive model of work and health, providing for an understanding of the differences in assumptions, vocabulary, research methods, and intervention approaches. Expanding communication to support interdisciplinary strategies, for example, is possible through shared journals, shared symposiums, or shared funding opportunities.22,126

WORKSHOP RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

On the basis of presentations from the 3 panels, workshop participants outlined a framework for a research agenda addressing chronic disease prevention that integrates health promotion and heath protection approaches in the workplace and takes into consideration the broader work–family community interface. Workshop participants identified cross-cutting research themes and priorities for future research, with particular attention paid to research priorities for coordinating and integrating the 3 parallel targets influencing worker health. After the workshop, participants further developed these themes in a series of conference calls; we consolidated these priorities, which were then vetted by the full group of participants. We identified 6 broad recommendations for future research (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Recommendations for Future Research: Workshop on Worksite Chronic Disease Prevention, May 21–22, 2009, Bethesda, MD

| Recommendation | Details |

| Assess intervention efficacy and characteristics associated with efficacy. | Assess the efficacy of interventions coordinating and integrating efforts to promote individual behavior change, improve the work environment, and address the work–family community interface (Figure 1). |

| Identify opportunities for improved coordination across formal and informal worksite policies, programs, and practices aimed at promoting and protecting worker health. | |

| Identify factors that contribute to the adoption of integrated interventions leading to both work environment changes and individual changes and to the participation of organizations and employees (or their representatives) regarding integrated interventions that change behaviors and policies and sustain behavioral and policy changes. | |

| Assess factors associated with differential effectiveness of interventions for worksites of varying sizes, industries, and groups within worksites (management, unions, individuals, workers’ families). | |

| Investigate the effectiveness of minimal intensity or default intervention strategies that require little up-front investment and deliver small doses to most workers with little initiative required by the individual worker, particularly in addressing health equity (e.g., for physical activity, policy changes that mandate exercise breaks or restrict nearby parking).58 | |

| Address a range of obstacles to participation in coordinated interventions among worksites (e.g., competing priorities, organizational commitment, corporate culture, costs, lack of staff expertise) and for individual workers (e.g., scheduling, long work hours, language, privacy concerns, or job control). | |

| Attend to population, job, and worksite characteristics. | Increase the generalizability of intervention research by systematically including a broad range of workers differing by age, occupation, income, education, language and literacy level, gender, race, ethnicity, comorbidities, family roles and responsibility, immigration status, urban or rural status, and socioeconomic position. |

| Assess intervention efficacy by job characteristics; job title; occupational status; full-time, part-time, or contingent status; schedule flexibility; site based vs off site (e.g., construction and transportation) | |

| Assess worksite intervention efficacy across a range of worksite characteristics, including industry, size, turnover rates, unionization status, rural vs urban location, public or private sector, and other key factors. | |

| Assess the interplay of organizational policies (formal and informal) and practices related to health promotion and health protection, roles of management structure and collective bargaining, leadership style (e.g., transactional, transformational), and management practices in supporting or inhibiting health program effectiveness, sustainability, and worker engagement. | |

| Assess factors associated with employers’ decisions in purchasing programs, including economic outcomes that may elucidate the business case for worksite health programs. | |

| Use appropriate study designs and methods. | Select methodologically rigorous and theory-based research designs appropriate to the research question and setting, including cluster randomized controlled trials, observational studies, panel and cohort studies, time series analyses, monitoring and surveillance studies, natural experiments, and qualitative studies. |

| Assess multilevel interventions (e.g., individual, interpersonal, family, workplace policies, and state and national legislative or regulatory policies using appropriate statistical techniques accounting for intraclass correlation and clustered data. | |

| Develop a registry of worksite health promotion and health protection efforts that would provide a means of tracking existing worksite health efforts over time. | |

| Use participatory research approaches that seek involvement of individuals and groups likely to be affected by worksite interventions, both work site based (e.g., employees, senior and middle management, employee health services, human resources, benefit plan, employee assistance, absence and disability management, medical, organization development, and labor unions) and community based (e.g., families, worker advocacy groups, committees on occupational safety and health, and occupational medicine clinics). | |

| Stimulate the use of mixed methods (quantitative and qualitative methods combined) and comparative case studies to gain access to in-depth descriptions of processes in the context of real-world environments that can aid in the identification of best practices and provide examples of practice-based evidence of successful programs. | |

| Apply appropriate and expanded measures and metrics. | Measure multiple exposures, processes, and outcomes, including morbidity, mortality, risk factors, health behaviors, incidence, presenteeism, absenteeism, work ability index, biological markers, quality-adjusted life years, organizational culture, economic measures (including return on investment, productivity, and related indicators), sustainability, process measures, work–family spillover, and crossover effects. |

| Develop parsimonious measures, such as health risk appraisal tools that incorporate health behaviors, occupational hazards, and work–family balance. | |

| Assess the wide range of hazardous occupational exposures, including toxic substances; long work hours, shiftwork, harassment, and other work stressors; organizational restructuring or downsizing; lean production; temporary or contract work; and telecommuting and home work.129 | |

| Examine potential mediators and moderators of intervention effectiveness, change, cost variables (cost-effectiveness, cost–benefit, and return on investment). Assess factors that document the mechanisms of change (e.g., intervention reach, levels of employee participation, dose delivered, dose received, fidelity to intervention objectives, implementation, and intervention exportability).72 Consider use of the RE-AIM model138 and assessment of size, scope, scalability, and sustainability139 | |

| Study sustainability and knowledge transfer. | Study the process of adaptation of evidence-based interventions for use with employees and special subgroups of workers at disproportionate risk of chronic disease (e.g.,. adaptation for low-wage workers, literacy and English as a Second Language concerns, shift workers) |

| Assess program adoption and implementation of packaged evidence-based worksite health promotion and health protection interventions. | |

| Conduct research on the process of knowledge transfer to identify factors that promote or inhibit program adoption, implementation, and maintenance within a range of worksite settings, including employee and management involvement. | |

| Address global concerns. | Assess the impact of competition on the global economy and policies related to globalization (e.g., deregulation, privatization) on working conditions, work–life balance, and health. |

| Identify ways to promote better work environments and employee health for employees of multinational corporations outside the United States | |

| Measure and redress health disparities in the United States and in a global context. |

Note. RE-AIM = Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance.

One recommendation was to assess intervention efficacy and characteristics associated with efficacy.48,140–142 Most worksite research conducted to date has focused independently on 1 of these 3 avenues of inquiry. Workshop participants placed a high priority on future research aimed at bridging the divide across the 3 domains (Figure 1). Testing the effects of integration on worker and family health outcomes across these 3 domains, as well as the effects of changes in the work environment, will be important. We defined interventions broadly across multiple levels, including changes in the work environment and policy changes as well as educational programs for workers and managers.

Research is needed to identify opportunities for synergy across the 3 intervention targets and to assess contributors to both program adoption and implementation of best practices. For example, interventions may be informed by research that explores the substantial source of stress for workers working and living with musculoskeletal pain, which can inhibit leisure-time exercise and lead to self-medication (e.g., unhealthy food, drugs, alcohol) for the pain and contribute to depression.143

Also, research is needed on the factors related to the adoption of integrated interventions and the participation of organizations, employee representatives, and individuals in integrated interventions that change behaviors and sustain the changes.

Similarly, research is needed to examine the impact of formal organizational policies and practices related to health promotion and health protection, management structure, leadership style (e.g., transactional, transformational), and informal management practices in supporting or inhibiting health programs.105,144

Attention must be paid to population, job, and worksite characteristics.50,67,98,100,131,145–149 A key theme across the 3 panel presentations was the persistence of disparities in worker health outcomes, access to worksite programs, and exposures in the work environment. Research is needed to identify ways to redress these disparities and ensure broad-based access to interventions across groups of workers, whether defined by occupation, gender, age, socioeconomic position, race or ethnicity, or other characteristics.

Alternative strategies to provide integrated interventions to blue-collar and other lower status workers, such as through occupational medicine clinics or collectively bargained programs, need to be explored. Such research must include a broad range of workers and worksites to ensure the generalizability of the research findings and to identify factors to improve targeting of interventions to specific groups of workers and worksites.

Consideration must be given to the selection of research designs and methods appropriate to the nature of the research question and the phase of research, including not only randomized controlled trials but also natural experiments and in-depth, mixed-methods, or comparative case studies.22,139,145,150,151 These methods must take into account the multilevel nature of this research, which requires multilevel designs that include assessments of management structures, support for workers and their families, and related organizational health outcomes.

Workshop participants also recommended the use of participatory approaches that engage a diverse population of employees in the planning and implementation of these efforts.

To permit comparisons across studies, researchers need to use standardized measures with demonstrated reliability and validity.30,139,152,153 A need exists for improved occupational exposure assessments for integrated work environment and health promotion interventions and for assessing the role of unions in worksite chronic disease prevention efforts. From an economic perspective, developing standard methods to measure cost savings and return on investment and creating standards for the calculation of return on investment (e.g., defining the elements that make up both the cost and the benefit sides of the equation) will be important.69–71,154,155 Workshop participants also discussed the need to monitor the application of integrated worksite programs, including by means of an integrated national worksite survey of employers to assess both program adoption and implementation.

Sustainability and knowledge transfer require study.156–159 Identifying methods to promote the use of evidence-based interventions and assessing their long-term sustainability is also important. Workshop participants stressed the need to minimize the transition from research into practice160 and to ensure that evidence-based interventions are effectively adapted and disseminated. Research on the dissemination process may identify methods to engage different types of worksites and organizational leaders, examine the motivational influence of financial and other incentives for worksite participation in chronic disease prevention, investigate the influence of family members on motivation to participate, and assess barriers to effective intervention delivery.

Workshop participants additionally noted that worksites exist in a global economy and that attention needs to be paid to promoting worker health and healthy work environments beyond US borders.161

CONCLUSIONS

Advancing this research agenda requires the creation and nurturing of transdisciplinary teams and identifying funding sources to support integrated studies. Research networks, centers of excellence, and other collaborative vehicles can promote research across disciplines and with diverse perspectives. Sustained funding of longitudinal research studies is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions that integrate health protection and health promotion strategies. Implementation of these research recommendations will require collaboration across funding bodies. New funding initiatives must cut across the National Institutes of Health and the CDC to foster research on multilevel interventions addressing the 3 intervention targets. In addition, relationships with journals should be developed to promote and support the dissemination of such research, for example, through special issues focused on the research priorities we have described. This research will also benefit from fostering graduate-level training programs that promote comprehensive and integrative approaches to health promotion and health protection.

Prevention of chronic disease among workers requires a partnership among federal and state public policymakers, employers, workers, labor union representatives, health professionals, and the surrounding community. In the face of an increasing chronic disease burden, rising health care costs, and health care reform, a critical part of the solution must involve addressing the health of workers. Promising evidence has pointed to the important role that the workplace may play in chronic disease prevention and control. These prevention efforts must also acknowledge the potential impacts of work-related factors on individual health behaviors through physical, social, organizational, and psychosocial mechanisms and potential exposures to hazards on the job that may directly influence work, family, and organizational health outcomes. Rigorous scientific evidence must be the cornerstone of the next generation of research on chronic disease prevention in the workplace. Articulation of a research agenda to enhance worker health in the context of healthy workplaces will require the engagement of policy, research, and funding organizations. This research will benefit from the contributions of scientists across disciplinary boundaries, including researchers focused on health behaviors and worksite health promotion, occupational safety and health, the work–family community interface, and the intersections between work and other sectors of workers’ lives. This workshop stimulated a dialogue across these disciplines and identified critical research that may ultimately promote and protect worker health. Systematic implementation of this research vision and effective dissemination of new models of interventions to support worker health outcomes are needed to address chronic disease prevention.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development; and the National Cancer Institute for their support. Glorian Sorensen's contributions were funded by the National Cancer Institute (grant 5 K05 CA108663-05) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (grant 5U19 OH008861-04).

We acknowledge the members of the Workshop Working Group: Audie A. Atienza, PhD, Cathy L. Backinger, PhD, MPH, Lisa Berkman, PhD, Rosalind Berkowitz King, PhD, Martin Cherniack, MD, MPH, Kathy Christensen, Michael Donovan, PhD, Lawrence Fine, MD, MPH, DrPH, Christine Hunter, PhD, ABPP, Barbara A. Israel, DrPH, MPH, Erin Kelly, PhD, Supriya Lahiri, PhD, James Merchant, MD, DrPH, Nico Pronk, PhD, FACSM, Laura Punnett, ScD, Teresa Schnorr, PhD, Mark A. Schuster, MD, PhD, Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH, Thomas M. Vogt, MD, MPH and Gregory R. Wagner, MD.

This article is based on findings and recommendations from a national workshop (May 21-22, 2009; Bethesda, MD) sponsored by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; the National Cancer Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not needed for this article.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chronic diseases and health promotion. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov.proxy-hs.researchport.umd.edu/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm. Updated 2009. Accessed February 27, 2010

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Leading causes of death. Available at: http://cdc.gov.proxy-hs.researchport.umd.edu/nchs/fastats/lcod.htm. Updated 2009. Accessed March 12, 2010

- 3.Office of Minority Health Diabetes data/statistics. Available at: http://www.omhrc.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=5. Updated 2009. Accessed March 12, 2010

- 4.Office of Minority Health Heart disease data/statistics. Available at: http://www.omhrc.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=6. Updated 2010. Accessed March 12, 2010

- 5.Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113(6):e85–e151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD fact book 2009: economic, environmental and social statistics. Available at: http://titania.sourceoecd.org/vl=1388841/cl=37/nw=1/rpsv/factbook2009/11/01/04/index.htm. Accessed February 25, 2010

- 7.Avendano M, Glymour MM, Banks J, Mackenbach JP. Health disadvantage in US adults aged 50 to 74 years: a comparison of the health of rich and poor Americans with that of Europeans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):540–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nolte E, McKee CM. Measuring the health of nations: updating an earlier analysis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(1):58–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chronic disease prevention and health promotion. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov.proxy-hs.researchport.umd.edu/chronicdisease/resources/publications/AAG/dhdsp.htm. Updated 2009. Accessed March 11, 2010

- 10.National Program of Cancer Registries National program of cancer registries: facts. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov.proxy-hs.researchport.umd.edu/cancer/npcr/about.htm. Updated 2009. Accessed March 11, 2010

- 11.American Diabetes Association Diabetes statistics. Available at: http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/diabetes-statistics. Accessed March 11, 2010

- 12.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):w822–w831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Research Council Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnall P, Dobson M, Rosskam E, Unhealthy Work: Causes, Consequences and Cures. Amityville, NY: Baywood; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Social Security Administration Annual statistical report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program. SSA publication no. 13-11826. Washington, DC: Social Security Administration; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelletier KR, Herman PM, Metz RD, Nelson CF. Health and medical economics: applications to integrative medicine. Explore (NY). 2010;6(2):86–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Issue Brief 4: Work and Health. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Correction: actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2005;293(3):293–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pronk NP, Lowry MK, Kottke TE, Austin E, Gallagher J, Katz A. The association between optimal lifestyle adherence and short-term incidence of chronic conditions among employees. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13(6):289–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorensen G, Barbeau E. Steps to a healthier US workforce: integrating occupational health and safety and worksite health promotion: state of the science. Paper presented at: The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health Steps to a Healthier US Workforce Symposium; October 26–28, 2004; Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stettler N, et al. Population-based prevention of obesity: the need for comprehensive promotion of healthful eating, physical activity, and energy balance. A scientific statement from American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Interdisciplinary Committee for Prevention. Circulation. 2008;118(4):428–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public health strategies for preventing and controlling overweight and obesity in school and worksite settings: a report on recommendations of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR. 2005;54(RR10):1–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Educational and community-based programs : Healthy People 2010. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000; 7-1–7-33 Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2010/Document/pdf/Volume1/07Ed.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poisal JA, Truffer C, Smith S, et al. Health spending projections through 2016: modest changes obscure part D's impact. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(2):w242–w253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koretz G. Employers tame medical costs: but workers pick up a bigger share. Bus Week. 2000;3664:26 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baicker K, Cutler D, Song Z. Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(2):304–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soler RE, Leeks KD, Razi S, et al. A systematic review of selected interventions for worksite health promotion: the assessment of health risks with feedback. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(2, suppl. 1):S237–S262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapman LS. Meta-evaluation of worksite health promotion economic return studies: 2005 update. Am J Health Promot. 2005;19(6):1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holzbach RL, Piserchia PV, McFadden DW, Hatwell TD, Herrman A, Fielding JE. Effect of a comprehensive health promotion program on employee attitudes. J Occup Med. 1990;32(10):973–978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics National Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries in 2008. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cfoi.pdf. Updated 2010. Accessed August 12, 2010

- 33.Steenland K, Burnett C, Lalich N, Ward E, Hurrell J. Dying for work: the magnitude of U.S. mortality from selected causes of death associated with occupation. Am J Ind Med. 2003;43:461–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics Workplace injuries and illnesses in 2008. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/osh.pdf. Updated 2009. Accessed August 12, 2010

- 35.Sengupta I, Reno V, Burton JF., Jr Workers’ compensation: benefits, coverage, and costs, 2007. Available at: http://www.nasi.org/research/2009/report-workers-compensation-benefits-coverage-costs-2007. Updated 2009. Accessed August 12, 2010

- 36.Leigh JP, Markowitz S, Fahs M, Landrigan P. Costs of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leigh JP, Markowitz SB, Fahs M, Shin C, Landrigan PJ. Occupational injury and illness in the United States: Estimates of costs, morbidity, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(14):1557–1568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Workplace Injury and Illness Summary. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. Gauging Control Technology and Regulatory Impacts in Occupational Safety and Health—An Appraisal of OSHA's Analytic Approach. Publication OTA-ENV-635. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silverstein M. Getting home safe and sound: occupational safety and health administration at 38. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):416–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Almeida DM, Wethington E, Chandler AL. Daily transmission of tensions between marital dyads and parent-child dyads. J Marriage Fam. 1999;61(1):49–61 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammer LB, Allen E, Grigsby TD. Work–family conflict in dual-earner couples: within-individual and crossover effects of work and family. J Vocat Behav. 1997;50(2):185–203 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Punnett L, Cherniack M, Henning R, Morse T, Faghri P; CPH-NEW Research Team. A conceptual framework for the integration of workplace health promotion and occupational ergonomics programs. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(suppl 1):16–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sorensen G, Barbeau E, Hunt MK, Emmons K. Reducing social disparities in tobacco use: a social contextual model for reducing tobacco use among blue-collar workers. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):230–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sorensen G, Himmelstein JS, Hunt MK, et al. A model for worksite cancer prevention: integration of health protection and health promotion in the WellWorks project. Am J Health Promot. 1995;10(1):55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Institute of Medicine Integrating Employee Health: A Model Program for NASA. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2005/Integrating-Employee-Health-A-Model-Program-for-NASA.aspx. Updated 2005. Accessed March 12, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carnethon M, Whitsel LP, Franklin BA, et al. Worksite wellness programs for cardiovascular disease prevention: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;120(17):1725–1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goetzel RZ, Ozminkowski RJ. The health and cost benefits of work site health-promotion programs. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:303–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.7-5: Worksite health promotion programs. : Healthy People 2010. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/data/midcourse/comments/faobjective.asp?id=7&subid=5. Accessed July 16, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Linnan L, Bowling M, Childress J, et al. Results of the 2004 National Worksite Health Promotion Survey. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1503–1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.US Small Business Administration FAQ: advocacy small business statistics and research. Available at: http://web.sba.gov/faqs/faqIndexAll.cfm?areaid=24. Accessed July 13, 2009

- 52.Cherniack M, Lahiri S. Barriers to implementation of workplace health interventions: an economic perspective. J Occup Environ Med. 2010; 52(9):934–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Early release of selected estimates based on data from the 2008 National Health Interview Survey. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov.proxy-hs.researchport.umd.edu/nchs/nhis/released200906.htm#7. Updated 2009. Accessed July 28, 2009

- 54.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crawford PB, Gosliner W, Strode P, et al. Walking the talk: fit WIC wellness programs improve self-efficacy in pediatric obesity prevention counseling. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(9):1480–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pohjonen T, Ranta R. Effects of worksite physical exercise intervention on physical fitness, perceived health status, and work ability among home care workers: five-year follow-up. Prev Med. 2001;32(6):465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lara A, Yancey AK, Tapia-Conyer R, et al. Pausa para tu salud: reduction of weight and waistlines by integrating exercise breaks into workplace organizational routine. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(1):A12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yancey AK. The meta-volition model: organizational leadership is the key ingredient in getting society moving, literally! Prev Med. 2009;49(4):342–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pronk SJ, Pronk NP, Sisco A, Ingalls DS, Ochoa C. Impact of a daily 10-minute strength and flexibility program in a manufacturing plant. Am J Health Promot. 1995;9(3):175–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pronk NP, Kottke TE. Physical activity promotion as a strategic corporate priority to improve worker health and business performance. Prev Med. 2009;49(4):316–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Galinsky T, Swanson N, Sauter S, Dunkin R, Hurrell J, Schleifer L. Supplementary breaks and stretching exercises for data entry operators: a follow-up field study. Am J Ind Med. 2007;50(7):519–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tullar JM, Brewer S, Amick BC, III, et al. Occupational safety and health interventions to reduce musculoskeletal symptoms in the health care sector. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(2):199–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kennedy CA, Amick BC, III, Dennerlein JT, et al. Systematic review of the role of occupational health and safety interventions in the prevention of upper extremity musculoskeletal symptoms, signs, disorders, injuries, claims and lost time. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(2):127–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jilcott S, Ammerman A, Sommers J, Glasgow RE. Applying the RE-AIM framework to assess the public health impact of policy change. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(2):105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Institute for Health Research RE-AIM. Available at: http://www.re-aim.org. Accessed February 27, 2010

- 66.Pronk NP, Goetzel RZ. The practical use of evidence: practice and research connected. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(2, suppl. 1):S229–S231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Linnan LA, Sorensen G, Colditz G, Klar DN, Emmons KM. Using theory to understand the multiple determinants of low participation in worksite health promotion programs. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28(5):591–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Linnan LA, Birken BE. Small businesses, worksite wellness, and public health: a time for action. N C Med J. 2006;67(6):433–437 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gold MR, Siegal JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC, Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neumann PJ. Using Cost-Effectiveness Analysis to Improve Health Care: Opportunities and Barriers. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Drummond MF, O'Brien B, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Linnan L. The Business Case for Employee Health: What We Know and What We Must Do. In press [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decision About Health, Wealth And Happiness. New York: Penguin Books; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Akerlof GA, Shiller RJ. Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ariely D. Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions. New York: HarperCollins; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hämäläinen P, Takala J, Saarela KL. Global estimates of fatal work-related diseases. Am J Ind Med. 2007;50(1):28–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Overall Evaluations of Carcinogenicity: An Updating of IARC Monographs Volumes 1–42, Supplement 7. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(12):1065–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schnall P, Belkic K, Landsbergis PA, Baker D. Why the workplace and cardiovascular disease. Occup Med. 2000;15(1):1–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Olsen O, Kristensen TS. Impact of work environment on cardiovascular diseases in Denmark. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1991;45(1):4–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Karasek RA, Theorell T, Schwartz JE, Schnall PL, Pieper CF, Michela JL. Job characteristics in relation to the prevalence of myocardial infarction in the US Health Examination Survey (HES) and the Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HANES). Am J Public Health. 1988;78(8):910–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Siegrist J, Rodel A. Work stress and health risk behavior. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(6):473–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kouvonen A, Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, et al. Effort-reward imbalance at work and the co-occurrence of lifestyle risk factors: cross-sectional survey in a sample of 36,127 public sector employees. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kivimaki M, Leino-Arjas P, Luukkonen R, Riihimaki H, Vahtera J, Kirjonen J. Work stress and risk of cardiovascular mortality: prospective cohort study of industrial employees. BMJ. 2002;325(7369):857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bongers PM, Kremer AM, Ter Laak J. Are psychosocial factors, risk factors for symptoms and signs of the shoulder, elbow, or hand/wrist? A review of the epidemiological literature. Am J Ind Med. 2002;41(5):315–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eby LT, Casper WJ, Lockwood A, Bordeaux C, Brinley A. Work and family research in IO/OB: content analysis and review of the literature (1980–2002). J Vocat Behav. 2005;66(1):124–197 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Allen TD, Herst DEL, Bruck CS, Sutton M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for future research. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5(2):278–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bureau of Labor Statistics Spotlight on statistics: older workers. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2008/older_workers. Updated 2008. Accessed July 13, 2009

- 89.Ilmarinen JE. Aging workers. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58(8):546–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tuomi K, Huuhtanen P, Nykyri E, Ilmarinen J. Promotion of work ability, the quality of work and retirement. Occup Med (Lond). 2001;51(5):318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ilmarinen J. Work ability–a comprehensive concept for occupational health research and prevention. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35(1):1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Alavinia SM, van Duivenbooden C, Burdorf A. Influence of work-related factors and individual characteristics on work ability among Dutch construction workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2007;33(5):351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kujala V, Tammelin T, Remes J, Vammavaara E, Ek E, Laitinen J. Work ability index of young employees and their sickness absence during the following year. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(1):75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liira J, Matikainena E, Leino-Arjasa P, et al. Work ability of middle-aged Finnish construction workers—a follow-up study in 1991–1995. Int J Ind Ergon. 2000;25(5):477–481 [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wegman D, McGee J, Health and Safety Needs of Older Workers. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Muntaner C, Eaton WW, Miech R, O'Campo P. Socioeconomic position and major mental disorders. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Landsbergis PA, Schnall PL, Belkic KB, Baker D, Schwartz J, Pickering TG. The workplace and cardiovascular disease. : Quick JC, Tetrick LE, Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology. 2nd ed Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2010:243–264 [Google Scholar]

- 98.Karasek RA., Jr Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285–308 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hallqvist J, Diderichsen F, Theorell T, Reuterwall C, Ahlbom A. Is the effect of job strain on myocardial infarction risk due to interaction between high psychological demands and low decision latitude? Results from Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program (SHEEP). Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(11):1405–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Landsbergis PA, Schnall PL, Pickering TG, Warren K, Schwartz JE. Lower socioeconomic status among men in relation to the association between job strain and blood pressure. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003;29(3):206–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.González MA, Rodríguez Artalejob F, Calero J. Relationship between socioeconomic status and ischemic heart disease in cohort and case-control studies: 1960-1993. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27(3):350–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kanjilal S, Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, et al. Socioeconomic status and trends in disparities in 4 major risk factors for cardiovascular disease among US adults, 1971-2002. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2348–2355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Grosch JW, Alterman T, Petersen MR, Murphy LR. Worksite health promotion programs in the U.S.: factors associated with availability and participation. Am J Health Promot. 1998;13(1):36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fisher BD, Golaszewski T. Heart check lite: modifications to an established worksite heart health assessment. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22(3):208–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Amick BC, III, Hogg-Johnson SJ. Managing Prevention With Leading and Lagging Indicators in the Workers Compensation System. : Utterback DS, Schnorr TM, Use of Workers’ Compensation Data for Occupational Injury and Illness Prevention—Proceedings From September 2009 Workshop. DHHS (NIOSH) document no. 2010-152. Washington DC: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schuster MA, Chung PJ, Elliott MN, Garfield CF, Vestal KD, Klein DJ. Awareness and use of California's Paid Family Leave Insurance among parents of chronically ill children. JAMA. 2008;300(9):1047–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kelly EL. Failure to update: an institutional perspective on noncompliance with the Family and Medical Leave Act. Law Soc Rev. 2010;44(1):33–66 [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hammer LB, Zimmerman KL. Quality of work life. : Zedeck S, ed-in-chief APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Vol. 3 Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010:399–431 [Google Scholar]

- 109.Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manage Rev. 1985;10(1):76–88 [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tavares LS, Plotnikoff RC. Not enough time? Individual and environmental implications for workplace physical activity programming among women with and without young children. Health Care Women Int. 2008;29(3):244–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Frone MR, Russel M, Cooper ML. Relation of work-family conflict to health outcomes: a four-year longitudinal study of employed parents. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1997;70(4):325–335 [Google Scholar]

- 112.Frone MR. Work-family conflict and employee psychiatric disorders: the National Comorbidity Survey. J Appl Psychol. 2000;85(6):888–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Greenhaus JH, Allen TD, Spector PE. Health consequences of work–family conflict: the dark side of the work–family interface. : Perrewé PL, Ganster DC, Employee Health, Coping and Methodologies. Bingley, UK: Emerald; 2006; 61–98 Research in Stress and Occupational Well Being; vol. 5 [Google Scholar]

- 114.Grzywacz JG, Bass BL. Work, family, and mental health: testing different models of work-family fit. J Marriage Fam. 2003;65(1):248–261 [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hammer LB, Cullen JC, Neal MB, Sinclair RR, Shafiro MV. The longitudinal effects of work-family conflict and positive spillover on depressive symptoms among dual-earner couples. J Occup Health Psychol. 2005;10(2):138–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Melchior M, Berkman LF, Niedhammer I, Zins M, Goldberg M. The mental health effects of multiple work and family demands: a prospective study of psychiatric sickness absence in the French GAZEL study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(7):573–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Grzywacz JG. Work-family spillover and health during midlife: is managing conflict everything? Am J Health Promot. 2000;14(4):236–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Väänänen A, Kalimo R, Toppinen-Tanner S, et al. Role clarity, fairness, and organizational climate as predictors of sickness absence: a prospective study in the private sector. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32(6):426–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ernst Kossek E, Ozeki C. Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: a review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research. J Appl Psychol. 1998;83(2):139–149 [Google Scholar]