Highlights

► Isothermal sections at 500 and 700 °C investigated. ► Vertical sections (partial at 10 at.% Si, complete at 40 at.% Si) determined. ► Partial ternary reaction scheme (Scheil diagram) established. ► New ternary compound identified.

Keywords: Al–Cu–Si system, Ternary phase diagram, Copper alloys, Aluminum alloys

Abstract

The phase equilibria and invariant reactions in the system Al–Cu–Si were investigated by a combination of optical microscopy, powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), differential thermal analysis (DTA) and electron probe micro analysis (EPMA). Isothermal phase equilibria were investigated within two isothermal sections. The isothermal section at 500 °C covers the whole ternary composition range and largely confirms the findings of previous phase diagram investigations. The isothermal section at 700 °C describes phase equilibria only in the complex Cu-rich part of the phase diagram. A new ternary compound τ was found in the region between (Al,Cu)-γ1 and (Cu,Si)-γ and its solubility range was determined. The solubility of Al in κ-CuSi was found to be extremely high at 700 °C. In contrast, no ternary solubility in the β-phase of Cu–Al was found, although this phase is supposed to form a complete solid solution according to previous phase diagram assessments. Two isopleths, at 10 and 40 at.% Si, were investigated by means of DTA and a partial ternary reaction scheme (Scheil diagram) was constructed, based on the current work and the latest findings in the binary systems Al–Cu and Cu–Si. The current study shows that the high temperature equilibria in the Cu-rich corner are still poorly understood and additional studies in this area would be favorable.

1. Introduction and literature review

Due to its importance in industry, the ternary system Al–Cu–Si has been heavily investigated over the last decades. Al–Cu–Si alloys are, for example, of growing importance for automotive industry due to its lightweight. The ternary alloys show higher strength than Al–Si alloys and their corrosion resistance is better than in Al–Cu alloys [1]. For designing ternary alloys matching specific requirements, fundamental understanding of the phase relationships and solidification behavior is essential. The Cu-rich corner of Al–Cu–Si and even of the binary subsystems Al–Cu and Cu–Si, are highly complex. Despite various studies of phase equilibria the ternary system is still not fully understood. Therefore we decided to perform a new re-investigation of the entire ternary system. A detailed literature review of existing phase diagram information on Al–Cu–Si and its binary subsystems is given below.

1.1. The binary Al–Cu system

The latest complete assessment of the system Al–Cu was done by Murray [2]. Her work describes the equilibrium phase diagram and provides some information on metastable phase equilibria as well. According to Murray, the system contains 12 intermetallic compounds, 7 of them are only stable at elevated temperatures. More recently, phase diagram investigations have been performed by Liu et al. [3] and Ponweiser et al. [4]. Riani et al. [5] published a phase diagram combining the results of Murray and Liu. In the Cu-poor phase diagram all the authors agree very well. The binary compound θ-Al2Cu shows a composition around 33 at.% Cu and crystallizes tetragonally [6]. It decomposes peritectically between 590(1) [4] and 592 °C [7]. At the composition of around AlCu, phase equilibria are more complicated. In the 1930s, Preston [8] found an orthorhombic structure in a sample quenched from 602 °C. Slowly cooled samples investigated by Bradley et al. [9] proposed an allotropic transformation Al1−δCu-η1 → AlCu-η2. Based on the comparison with the work of Preston, an orthorhombic or monoclinic structure was suggested for the low temperature phase. El-Boragy et al. [10] showed that the structure of the low-temperature phase was monoclinic. Murray does not explicitly mention the order of the transition from the high- to the low-temperature phase but according to the phase diagram given in [2] she assumes a higher order transition. Investigations by high-temperature X-ray diffraction worked out recently by the present authors revealed the structure of the high-temperature η1-phase to be of the Al1−δCu-type (Space group: Cmmm) [4]. Based on differential thermal analysis (DTA) as well as structural analysis, Ponweiser et al. [4] indicate that the transition η1 → η2 is a first order transition.

Compounds with the approximate composition Al3Cu4 were also found to show a high- and a low-temperature modification [8,9]. Murray suggests a transition temperature between 530 and 570 °C depending on the composition of the phase. Dong et al. [11,12] investigated annealed and as-cast samples with a composition of Al3Cu4. The as-cast samples exhibit a mixture of an orthorhombic face-centered and an orthorhombic body-centered structure and a minimum amount of γ-Al4Cu9. After annealing at 500 °C the orthorhombic face-centered structure became the major phase. The authors therefore suggested a transition γ-Al4Cu9 + oI = oF. EPMA measurements indicated compositions of Al43.2Cu56.8, Al41.3Cu58.7 and Al39.6Cu60.4 for oF, oI and γ-Al4Cu9, respectively. In the assessment of Murray, “oI” is labeled ζ1 and “oF” is labeled ζ2. Gulay and Harbrecht determined the structures of ζ1 (Fmm2, structure type Al3Cu4) [13] and ζ2 (Imm2, structure type Al3Cu4−δ) [14]. Contrary to Dong et al., Gulay and Harbrecht dedicate the face-centered structure to the phase with the higher Cu-content. Additional thermal analysis showed that the Cu-rich phase ζ1 (sample composition Al42.5Cu57.5) is stable at 400 °C [13] and the Cu-poorer phase ζ2 (sample composition Al43.2Cu56.8) is stable at elevated temperatures (530 °C) and does not resist thermal treatment at 400 °C [14]. This is not in agreement with Murray who describes a low temperature phase ζ2 and a high temperature phase ζ1 with a slightly higher Cu-content [2]. As mentioned above, the transition temperature is supposed to be between 530 and 570 °C. Our own new investigations find ζ1 not to be stable at 500 °C, indicating a transition temperature ζ2 = ζ1 + η2 above 500 °C.

The high temperature phases ɛ1 and ɛ2 were determined by Stockdale [15], the structure of ɛ2 was found to be hexagonal [10]. The structure of the ɛ1-phase, stable at elevated temperatures, is still unknown. The order of the transition ɛ1–ɛ2 is not mentioned specifically in literature but according to established phase diagrams it is a higher order transition [2,4].

The region between 60 and 70 at.% Cu shows according to Murray two different compounds stable at room temperature, δ and γ1 [2], while a third phase with unknown structure was not included in the assessment due to non-consensus in literature. The structure of δ was determined by Kisi and Brown [16], γ1 was revealed by Arnberg and Westman [17]. The high temperature structure γ0 was investigated by Liu et al. who found a bcc structure of the Cu5Zn8-type. The assessment of Murray proposes a two-phase field between γ0 and γ1 based on the work of Hisatsune [18,19]. Liu et al. investigated the Cu-rich part by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), high-temperature X-ray diffraction and diffusion couples and did not find a two-phase field between γ0 and γ1 thus proposing a higher order transition between the two phases. This finding was confirmed recently by Ponweiser et al. [4].

The assessment of Murray claims that a high temperature phase β0 is formed peritectically from β and liquid at 1037 °C. The phase was determined by Dawson [20] metallographically and by dilatometry measurements but has, according to Murray, never been reconfirmed. New diffusion couple experiments of Liu et al. [3] did not confirm the existence of β0 either. Additional investigations by DSC measurements revealed only an effect at 1019 °C which is rather connected to the solidus of β than the eutectoid reaction β0 = β + γ0. This interpretation was confirmed by Ponweiser et al. [4].

The two-phase region between β and (Cu) was heavily investigated and the assessment of Murray [2] gives a broad overview about the results of this research. The temperature of the eutectoid reaction β = γ1 + (Cu) was found between 560 and 575 °C which can be explained by the sluggishness of the reaction.

The α2-phase is stable below 363 °C [2]. According to Murray's assessment α2 has an ordered fcc structure with a long period superlattice based on Cu3Au and Al3Ti. Adorno et al. [21] give a more detailed description of the phase α2.

An overview about the invariant reactions in the system used in the current study is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Invariant reactions in the binary subsystems used in the current work.

| Phase reaction | Composition of the involved phases/at.% | Temperature (°C) | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al–Cu | |||||

| L = β | – | 75 Cu | – | 1052(5) | [4] |

| L = (Cu) + β | 83.0(5) Cu | 84.5(5) Cu | 82.0(5) Cu | 1035(5) | [4] |

| β + L = γ0 | 69.0(5) Cu | 63.0(5) Cu | 65.0(1) Cu | 993(2) | [4] |

| γ0 + L = ɛ1 | 65.5(5) Cu | 60.0(5) Cu | 64.5(5) Cu | 960(2) | [4] |

| γ1 + ɛ1 = ɛ2 | 64.0(5) Cu | 62.5(5) Cu | 62.5(5) Cu | 847(1) | [4] |

| ɛ1 = ɛ2 + L | 59.5(5) Cu | 59.5(5) Cu | 52.5(5) Cu | 847(1) | [4] |

| γ0 = γ1 | – | 69.0 Cu | – | ∼800 | [4] |

| – | 65.0 Cu | – | 874(2) | [4] | |

| γ1 + ɛ2 = δ | 63.0(5) Cu | 58.5(5) Cu | 61.5(5) Cu | 684(1) | [4] |

| ɛ2 + L = η1 | 54.5(5) Cu | 38.5(5) Cu | 52.0(5) Cu | 625(2) | [4] |

| ɛ2 + η1 = ζ2 | 56.5(5) Cu | 53.0(4) Cu | 55.5(5) Cu | 597(1) | [4] |

| η1 + L = θ | 51.5(5) Cu | 32.5(5) Cu | 33.5(5) Cu | 591(2) | [4] |

| ζ2 + η1 = η2 | 54.5(5) Cu | 52.5(5) Cu | 53.5(5) Cu | 580(1) | [4] |

| ɛ2 = δ + ζ2 | 57.5(5) Cu | 60.0(5) Cu | 56.0(5) Cu | 578(2) | [4] |

| η1 = η2 + θ | 52.0(5) Cu | 52.5(5) Cu | 33.5(5) Cu | 574(3) | [4] |

| β = (Cu) + γ1 | 76.0(5) Cu | 81.5(5) Cu | 70.0(5) Cu | 567(2) | [4] |

| δ + ζ2 = ζ1 | 60.0(5) Cu | 56.5(5) Cu | 57.0(5) Cu | 561(2) | [4] |

| L = θ + (Al) | 17(1) Cu | 32.0(5) Cu | 2.5(5) Cu | 550(2) | [4] |

| γ1 + (Cu) = α2 | 69 Cu | 80.3 Cu | 77.25 Cu | 363 | [2] |

| Al–Si | |||||

| L = Al + Si | 12.2(1) Si | 1.5(1) Si | 100 Si | 577(1) | [22] |

| Cu–Si | |||||

| L + (Cu) = β | 84.0(5) Cu | 89(1) Cu | 85.8(5) Cu | 849(2) | [25] |

| (Cu) + β = κ | 89(1) Cu | 85.5(5) Cu | 87.5(5) Cu | 839(2) | [25] |

| L + β = δ | 80.8(5) Cu | 83.5(5) Cu | 82.5(5) Cu | 821(2) | [25] |

| L = η + δ | 80.2(4) Cu | 76.8(5) Cu | 82.3(5) Cu | 818(3) | [25] |

| L = (Si) + η | 70(1) Cu | 0 Cu | 74.0(5) Cu | 807(2) | [25] |

| η + δ = ɛ | 76.5(5) Cu | 81.5(5) Cu | 78.95 Cu | 800(2) | [25] |

| β = δ + κ | 83.8(5) Cu | 83.0(5) Cu | 85.8(5) Cu | 781(2) | [25] |

| δ = ɛ + γ | 82.1(5) Cu | 78.95(1) Cu | 82.2(5) Cu | 735(2) | [25] |

| δ = γ + κ | 83.1(5) Cu | 82.5(5) Cu | 86.8(5) Cu | 734(2) | [25] |

| η + ɛ = η′ | 75.8(5) Cu | 78.95 Cu | 75.8(5) Cu | 618(3) | [25] |

| η′ + ɛ = η″ | 75.6(5) Cu | 78.95 Cu | 75.6(5) Cu | 570 | [25] |

| η = (Si) + η′ | 74(1) Cu | 0 Cu | 74(1) Cu | 555(3) | [25] |

| κ = γ + (Cu) | 89 Cu | 83 Cu | 90 Cu | 552 | [25] |

| η′ = η″ + (Si) | 0 Cu | 74(1) Cu | 74(1) Cu | 467 | [25] |

1.2. The binary Al–Si system

The binary Al–Si system is a simple eutectic system and was assessed by Murray and McAlister extensively [22].

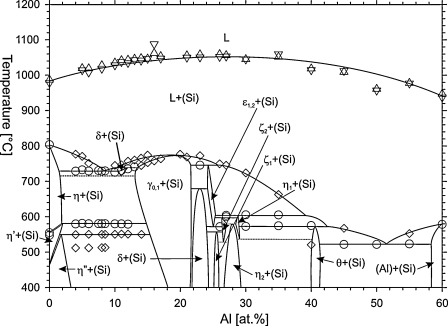

1.3. The binary Cu–Si system

The system Cu–Si has been investigated intensively in the last decades. A critical assessment was done by Olesinski and Abbaschian [23] giving an extensive overview about the work done in solid and liquid solutions as well as on metastable phases reported in literature up to the 1980s. A more recent thermodynamic description of the system has been given by Yan and Chang [24], experimental investigations with focus on the Cu-rich part have recently been performed by Sufryd et al. [25]. An overview about the invariant reactions in the system is given in Table 1.

The binary compounds are all formed in the Cu-rich part of the phase diagram, starting with Cu3Si. This phase shows three different modifications, the high-temperature η-phase, an intermediate phase η′ and the low temperature phase η″. It must be noted that the nomenclature of the phases is not consistent in old literature. The high temperature phase melts congruently at 859 °C and the transition temperatures between the modifications differ highly with composition. The transition temperature of η to η′ takes place between 558 and 620 °C, the transition temperature between η′ and η″ differs between 467 and 570 °C, for the Cu-poor and Cu-rich side, respectively. According to the assessed phase diagram, the phases η and η′ [26] show a rhombohedral structure (R-3m and R-3) whereas η″ is orthorhombic [26] or tetragonal [27]. Solberg [26] claims that η′ has an ordered superstructure and η″ exhibits a long-period superstructure which is derived from the η′-structure by periodic displacement. The high-temperature phase η shows a disordered structure. More recent transmission electron investigations by Wen and Spaepen indicate P-3m1 and R-3 as space groups for η and η′ [28]. Rapid quenching experiments performed by Mattern et al. [29] confirm the structure type of η.

The existence of the phase with the nominal composition Cu15Si4, designated ɛ, is widely discussed in literature. The assessment includes the phase in the stable binary phase diagram [23], even though previous authors found different results. The phase was described first by Arrhenius and Westgren [30], Mukherjee et al. described a possible phase transition around 600 °C which was not confirmed. Diffusion couple experiments showed only one intermetallic phase, Cu3Si [31,32] in the system. The authors suspected retarded nucleation of the other phases. By contrast, thin film diffusion couple experiments prepared by sputter deposition exhibit all three expected intermetallic compounds, Cu3Si, ɛ and γ [33,34]. Rapidly quenched samples do not show ɛ but after subsequent annealing at 500 °C ɛ is present [29]. In their study about the ternary Al–Cu–Si system Riani et al. claim that ɛ is stabilized by impurities and not present in the binary if very pure basic materials are used [35]. This conclusion was later withdrawn by the same authors in a recent study of the Cu–Si binary system by Sufryd et al. [25]. The authors conclude that the formation of ɛ is only inhibited kinetically but that the phase is stable in the binary Cu–Si system [25].

The third intermetallic compound stable at low temperature is Cu5Si, designated as γ. It is cubic, showing the β-Mn structure, and it forms peritectically at 729 °C [23]. Although the phase does not occur in some diffusion couple experiments [31,32], it is considered stable at the indicated temperature.

Three phases are reported to be stable at elevated temperature, κ, β and δ. The phase κ forms at 842 °C and decomposes eutectically at 552 °C. The compound crystallizes hexagonally in the Mg-type structure [23,29]. β forms peritectically from (Cu) and liquid at 852 °C and decomposes eutectically into δ and γ at 785 °C. It crystallizes cubic a in W-type structure [23]. According to the assessment of Olesinski and Abbaschian, the phase δ forms peritectically from β and liquid at 824 °C and decomposes at 710 °C eutectically into ɛ and γ [23]. New investigations by Sufryd et al. [25] indicate a congruent transformation from γ to δ and two eutectoidic reactions at 735 °C. High-temperature X-ray diffraction experiments performed by Mukherje et al. described the phase as tetragonal [27]. Splat cooling experiments of Mattern et al. [29] lead to the hexagonal symmetry P63/mmc but the structure could not be confirmed by recent investigations [25].

1.4. The ternary system Al–Cu–Si

The first investigations of the whole system have been performed by Matsuyama [36] and Hisatsune [18]; a critical assessment is given by Lukas and Lebrun [37]. The authors give an overview about the present phases in the binaries as well as information on invariant ternary equilibria including a liquidus surface projection. According to this assessment, no ternary compounds are present. An isothermal section at 400 °C based on the work of Hisatsune [18] together with a tentative reaction scheme (Scheil diagram) completes the assessment.

The largest part of the ternary system is dominated by phase equilibria with (Si), since most binary phases only occur in the Cu-rich part and there are no ternary phases reported. At 400 °C γ1-Al4Cu9 shows the highest solubility into the ternary. The phase is stable up to the approximate composition Al17Cu72Si11. The compounds δ-Al4Cu9 (∼1 at.% Si), γ-Cu5Si (∼2 at.% Al), ɛ-Cu15Si4 (∼2 at.% Al) and η″-Cu3Si (∼5 at.% Si) show solubilities, too [37]. There is no information given on the solubility of ζ1/ζ2-Al3Cu4, η2-AlCu and θ-Al2Cu since the isothermal section given by Lukas and Lebrun only covers the section with a Cu-content higher than 60 at.%. The three phase fields in the Cu-rich corner present at 400 °C are: {(Cu) + (Al,Cu)-γ1 + (Cu,Si)-κ}, {(Cu,Si)-η″ + (Al,Cu)-γ1 + (Cu,Si)-κ}, {(Cu,Si)-ɛ + (Cu,Si)-η″ + (Cu,Si)-κ}, {(Cu,Si)-ɛ + (Cu,Si)-η″ + (Cu,Si)-γ} and {(Cu,Si)-γ + (Cu,Si)-κ + (Cu)} [37].

Additional isothermal sections at 500 and 600 °C are given by He et al. [38]. According to He et al. the three phase fields in the Cu-rich corner present at 500 °C are: {(Cu) + (Al,Cu)-γ1 + (Cu,Si)-κ}, {(Cu,Si)-η + (Al,Cu)-γ1 + (Cu,Si)-ɛ}, {(Cu,Si)-ɛ + (Al,Cu)-γ1 + (Cu,Si)-κ}, {(Cu,Si)-ɛ + (Cu,Si)-γ + (Cu,Si)-κ} and {(Cu,Si)-γ + (Cu,Si)-κ + (Cu)}. The solubilities change slightly compared to the isothermal section at 400 °C. The phase γ1-Al4Cu9 for example is stable up to the composition Al15Cu74Si11. At 600 °C, the additional three phase field {(Cu) + (Al,Cu)-β + (Al,Cu)-γ1} appears, where (Al,Cu)-β shows a solubility of about 4 at.% Si. Both at 500 and 600 °C, He et al. allocate the binary phase Cu3Si to Cu3Si-η, which is contradicting to the binary Cu–Si system [23,29,39].

He et al. also present several calculated vertical sections and a Scheil diagram which differs from the one proposed by Lukas and Lebrun [37] concerning the reactions temperatures as well as the reactions itself. Further thermodynamic measurements and assessments have been performed by various authors [1,40–44].

The latest experimental investigation was done by Riani et al. [35]. The extensive study consists of an isothermal section at 500 °C and a detailed description of the existence of ɛ-Cu15Si4 in the binary and ternary system. As mentioned above, Sufryd et al. [25] give a more detailed study on the ɛ-Cu15Si4 phase, which is considered to be stable in the binary. Considering the findings of Sufryd et al. [25] the isothermal section given by Riani et al. [35] shows the same three phase fields like described by He et al. [38] although the solubility ranges especially for (Cu), κ-Cu7Si and γ1-Al4Cu9 are quite different.

2. Experimental

The samples were prepared from aluminum slug (99.999%), copper wire (99.95%) and silicon lump (99.9999%), all supplied by Alfa Aesar, Karlsruhe, Germany. For cleaning from oxides, the Cu wire was treated in a H2-flow at 300 °C for approximately 3 h. The calculated amounts of aluminum, copper and silicon were weighted to an accuracy of 0.05 mg. Sample homogenization was done in an Edmund Buehler MAM-1 arc furnace with a water-cooled copper plate and zirconium as a getter material. The resulting slug was turned and re-melted two times for homogenization. In order to prevent reactions with the quartz glass surface, the resulting bead was wrapped in Molybdenum foil (99.97%, Plansee SE, Reutte, Austria) before placing it in a quartz glass tube. The ampoules were sealed under vacuum and placed in a muffle furnace for 28 days. After annealing, the samples were quenched in cold water and prepared for further investigation. The occurring mass loss during the whole sample preparation procedure usually was below 1% and therefore not considered to affect the sample composition significantly. Representative sections of the annealed samples were investigated by means of optical microscopy using a Zeiss Axiotech 100 microscope. For phase determination, X-ray powder diffraction analysis was performed using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE Diffractometer operating in reflection mode (Cu Kα1 radiation, Lynxeye silicon strip detector). For evaluation of the resulting diffractograms the software TOPAS [45] was used.

Selected samples showing three phases in powder X-ray analysis or two-phase samples required for the definition of specific tie-lines were analyzed by means of Electron Probe Micro Analysis (EPMA). EPMA measurements were carried out using a Cameca SX electron probe 100 (Cameca, Courbevoie, France) operating with wavelength dispersive spectroscopy (WDS) for quantitative analysis. The measurements were carried out at 15 kV using a beam current of 20 nA with pure elements as standard materials. Conventional ZAF matrix correction was use to calculate the final composition from the measured X-ray intensities. In order to rule out inhomogeneity, measurements of the composition of the respective phases usually were performed at three different spots. The measured sample composition did not depend on the location within the sample.

DTA measurements were performed on a Setaram Setsys Evolution 2400 (Setaram Instrumentation, Caluire, France) and a Netzsch DTA 404 PC (Netzsch, Selb, Germany). Both measurement devices are operated using Pt/Pt–10%Rh thermocouples (Type S) which were calibrated using the melting points of pure Sn, Au and Ni. The samples with a weight of approximately 20 mg were placed in open alumina crucibles and measured employing a slow permanent argon flow. Applying a heating rate of 5 K min−1, two heating- and cooling-curves were routinely recorded for each sample to check reproducibility of thermal effects. The possible mass loss during the DTA investigations was checked routinely and no relevant mass changes were observed.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Isothermal section at 500 °C

The isothermal section of the phase diagram is shown in Fig. 1. The composition of the limiting phases in the three phase fields colored in dark grey is determined by EPMA measurements. The three phase fields in light grey have been determined by measuring samples in the limiting two phase fields because of lack of a sample in the respective three phase field. An overview about three phase fields and selected tie-lines measured by EPMA is given in Table 2. A selection of images in the back scattered electron mode (BSE) showing the microstructures of annealed samples is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Isothermal section at 500 °C. Black: single phase fields, dark grey: three phase fields determined by EPMA measurements, light grey fields: three phase fields determined by analysis of the neighboring two phase fields, dotted black lines: tie-lines measured by EPMA.

Table 2.

Overview about selected three- and two-phase fields at 500 and 700 °C determined in the present study.

| Phase field | Temperature | Nominal composition of the respective sample | Phase composition |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Al | Cu | Si | |||

| {(Al) + θ + (Si)} | 500 | Al50Cu10Si40 | (Al) | 96.0(10) | 3.0(10) | 1.0(10) |

| θ | 68.0(10) | 31.0(10) | 1.0(10) | |||

| (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a | |||

| {η2 + (Si) + θ} | 500 | Al35Cu25Si40 | η2 | 49.7(2) | 50.2(1) | 0.1(1) |

| (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a | |||

| θ | 66.6(3) | 32.4(3) | 1.0(1) | |||

| {η2 + (Si)} | 500 | Al42Cu48Si10 | η2 | 46.8(2) | 53.2(2) | 0.1(1) |

| (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a | |||

| {δ + (Si) + ζ1} | 500 | Al37Cu53Si10 | δ | 41.0(10) | 59.0(10) | 0.0(10) |

| (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a | |||

| ζ1 | 42.0(10) | 58.0(10) | 0.0(10) | |||

| {(Si) + ζ1} | 500 | Al25Cu35Si40 | (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a |

| ζ1 | 42.6(2) | 57.3(2) | 0.1(1) | |||

| {δ + (Si)} | 500 | Al10Cu55Si10 | δ | 39.7(2) | 0.1(1) | 60.2(1) |

| (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a | |||

| {γ1 + (Si)} | 500 | Al20Cu40Si40 | γ1 | 33.4(2) | 0.6(2) | 65.4(2) |

| (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a | |||

| {η′ + γ1 + (Si)} | 500 | Al10Cu50Si40 | η′ | 3.0(10) | 76.0(10) | 21.0(10) |

| γ1 | 25.0(10) | 69.0(10) | 6.0(10) | |||

| (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a | |||

| {ɛ + κ} | 500 | Al10Cu80Si10 | ɛ | 1.3(1) | 78.5(1) | 20.2(1) |

| κ | 11.4(2) | 80.2(2) | 8.3(1) | |||

| {ɛ + γ1 + κ} | 500 | Al6Cu78Si16 | ɛ | 2.0(10) | 78.0(10) | 20.0(10) |

| γ1 | 16.4(1) | 73.6(1) | 10.0(1) | |||

| κ | 14.1(1) | 77.8(1) | 8.1(1) | |||

| {γ1 + κ} | 500 | Al25Cu72.5Si2.5 | γ1 | 28.6(2) | 69.1(1) | 2.3(1) |

| κ | 17.2(1) | 78.6(2) | 4.2(1) | |||

| Al17Cu75Si8 | γ1 | 18.7(2) | 72.8(2) | 8.5(1) | ||

| κ | 14.6(1) | 77.7(1) | 7.7(1) | |||

| {(Cu) + γ} | 500 | Al2Cu86Si12 | (Cu) | 3.3(2) | 87.6(3) | 9.1(3) |

| γ | 0.6(1) | 82.9(1) | 16.5(2) | |||

| {γ + κ} | 500 | Al3Cu82Si15 | γ | 2.3(1) | 81.1(1) | 16.6(1) |

| κ | 8.5(1) | 82.5(1) | 9.0(1) | |||

| {ɛ2 + γ1 + (Si)} | 700 | Al38Cu60Si2 | ɛ2 | 39.6(3) | 60.2(3) | 0.2(1) |

| γ1 | 38.3(3) | 61.5(2) | 0.2(1) | |||

| (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a | |||

| {γ1 + (Si)} | 700 | Al30Cu60Si10 | γ1 | 33.2(3) | 65.9(2) | 0.9(2) |

| (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a | |||

| Al25Cu60Si15 | γ1 | 28.1(3) | 68.2(2) | 3.7(1) | ||

| (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a | |||

| {η + γ1 + (Si)} | 700 | Al10Cu60Si30 | η | 1.8(1) | 76.4(1) | 21.8(2) |

| γ1 | 19.5(2) | 71.2(1) | 9.2(2) | |||

| (Si) | 0a | 0a | 100a | |||

| {η + γ1} | 700 | Al10Cu75Si15 | η | 2.5(1) | 76.7(1) | 20.8(1) |

| γ1 | 16.0(10) | 74.0(10) | 10.0(10) | |||

| {ɛ + τ} | 700 | Al5Cu77Si18 | ɛ | 2.9(1) | 76.9(1) | 20.2(1) |

| τ | 9.1(3) | 77.2(1) | 13.7(2) | |||

| Al4Cu78Si18 | ɛ | 2.3(1) | 77.2(1) | 20.5(2) | ||

| τ | 6.0(2) | 78.8(1) | 15.2(2) | |||

| {γ + κ} | 700 | Al3Cu82Si15 | γ | 2.6(1) | 80.9(3) | 16.5(3) |

| κ | 3.6(1) | 83.7(2) | 12.7(1) | |||

| Al5Cu80Si15 | γ | 4.9(1) | 79.7(2) | 15.4(1) | ||

| κ | 6.1(1) | 82.2(1) | 11.7(1) | |||

| {κ + τ} | 700 | Al7Cu80Si13 | κ | 7.7(1) | 81.2(2) | 11.1(1) |

| τ | 6.6(1) | 79.0(1) | 14.4(1) | |||

| Al12Cu77Si11 | κ | 13.0(1) | 79.1(1) | 7.9(2) | ||

| τ | 11.8(2) | 76.5(1) | 11.7(1) | |||

| {γ1 + κ} | 700 | Al20Cu75Si5 | γ1 | 22.1(2) | 71.8(2) | 6.1(1) |

| κ | 19.2(2) | 76.6(3) | 4.2(1) | |||

| Al26Cu72Si2 | γ1 | 23.3(1) | 75.1(1) | 1.6(1) | ||

| κ | 28.0(1) | 69.9(2) | 2.1(1) | |||

| {(Cu) + κ} | 700 | Al18Cu80Si2 | (Cu) | 16.5(1) | 81.8(2) | 1.7(1) |

| κ | 20.1(1) | 77.7(1) | 2.2(2) | |||

| Al5Cu86Si9 | (Cu) | 5.4(2) | 86.3(3) | 8.3(2) | ||

| κ | 4.8(2) | 85.4(2) | 9.8(2) | |||

No considerable solubility of Al or Cu in Si.

Fig. 2.

BSE images of samples with the nominal composition (A) Al10Cu80Si10 (500 °C), (B) Al6Cu78Si16 (500 °C), (C) Al17Cu73Si10 (500 °C) and (D) Al7Cu80Si13 (700 °C).

The Cu-poor region of the isothermal section shows Si in equilibrium with various binary Al–Cu compounds. The binary Al–Cu compounds in this region show very limited solubility of Si. (Al,Cu)-θ shows the highest solubility of Si with about 1 at.%. The phases (Al,Cu)-η2, (Al,Cu)-ζ1 and (Al,Cu)-δ do not show any solubility of Si at all. Two of the three phase fields in this region, {η2 + (Si) + ζ1} and {δ + γ1 + (Si)} could not be determined by EPMA due to the lack of samples in the respective three phase field. However, their existence is well documented by measurements in adjacent two phase fields (comp. Table 2).

The most Cu-rich phase field with (Si) is {γ1 + Cu3Si-η′ + Si}. Phases with the composition Cu3Si show three isomorphic structures which transform very easily and therefore it was not possible to quench the respective phases stable at high temperature. Identification of the respective powder-XRD pattern was done by comparison with a sample in the two-phase region Cu3Si–(Si). Following the binary phase diagram [25], the three phase field contains the phase Cu3Si-η′, rather than the low temperature phase Cu3Si-η″ or the high temperature phase Cu3Si-η.

The Cu-rich part of the isothermal section shows a more complicated situation dominated by extended solid solutions. The only three phase field determined directly by EPMA measurements is {ɛ + γ1 + κ}. The limiting compounds of the remaining three phase fields as well as their solubility ranges have been determined by analysis of several samples in the respective two phase regions. The remaining three phase fields are: {(Cu) + γ1 + κ}, {(Cu) + γ + κ}, {ɛ + γ + κ} and {ɛ + γ1 + η″-Cu3Si}. A very narrow three phase field {η′ + η″ + γ1} should also be present but was not included in the isothermal section due to reasons of clarity.

The binary compounds in the Cu-rich part of the phase diagram show a considerable ternary solubility of Si and Al, respectively. The phase γ1 is stable up to the composition Al18Cu72.2Si9.8. η″-Cu3Si, ɛ and γ show a solubility of 2.4, 2 and 2 at.% Al, respectively.

In the binary, the compound (Cu,Si)-κ is only stable between 570 and 839 °C [25]. By addition of (Al) it is stable at 500 °C between Al8Cu74Si8, Al14Cu68Si8 and Al17Cu78.5Si4.5. Pure Cu shows a high solubility of Al and Si as indicated by the binary phase diagrams [4,25].

The determined three phase fields in general in good agreement with Riani et al. [35], although the composition of the limiting phases is slightly different. Contrary to Riani, the phase (Cu,Si)-ɛ is shown as stable binary compound in agreement with recent literature [25].

The phase (Al,Cu)-γ1 was found to be stable up to the composition Al18Cu72.2Si9.8 compared to Al14.5Cu74Si11.5 found by [35]. The phase with the composition Cu3Si shows a solubility of 2.4 at.% Al in the current work compared to 4.8 at.% in [35]. The solubility ranges of (Cu,Si)-ɛ are in the same range in both cases (2 at.% Al compared to 1.5 at.% Al in [35]). The phase (Cu,Si)-γ shows a broader solubility range in the binary (from 17 to 20 at.% Cu) in the work of Riani which is not in agreement with recent literature (16–18 at.% Cu in [25]). The phase dissolves up to 2 at.% Al in both, the current work as well as in the isothermal section published by Riani et al. [35].

Riani et al. propose a two phase field of about 1.5 at.% width [35] between (Cu) and (Cu,Si)-κ in the ternary phase diagram. In the current work, samples with the nominal composition Al11Cu82Si7, Al13Cu81Si6 and Al15Cu80Si5 were placed in this region. X-ray powder diffraction of the respective samples shows pure (Cu,Si)-κ for the sample with the nominal composition Al11Cu82Si7, and a mixture of (Cu,Si)-κ and (Cu) for the other two samples. Due to the very low amount of Cu in the samples, implied by the low intensity of the Cu-related peaks in the diffractograms, it was not possible to analyze these samples properly by means of EPMA. Therefore, the Si-poor boundary of the phase (Cu,Si)-κ was estimated using the sample Al11Cu82Si7 in the single phase field (Cu,Si)-κ and the sample Al13Cu81Si6 and Al15Cu80Si5 in the two phase field {(Cu,Si)-κ + (Cu)} with a very low Cu-content. The solubility of (Al) and (Si) in Cu were estimated based on the solubility of Al and Si in (Cu) in the binary sub-systems and tie-lines in the two phase field {(Cu,Si)-γ + (Cu)}. The phase (Cu,Si)-κ is stable up to the composition Al5Cu85.5Si9.5 in the work of Riani et al. [35] compared to Al8Cu84Si8 in the current work.

3.2. Isothermal section at 700 °C

According to the binary phase diagram [25], at 700 °C Cu3Si shows the high temperature structure η. Fine black lines in Fig. 3 indicate tie-lines as measured by EPMA analysis of different samples. These measurements allow determining the remaining three phase fields as well as the approximate composition of the limiting phases. A selection of measured tie-lines at 700 °C is given in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Isothermal section at 700 °C. Black: single phase fields, dark grey: three phase fields determined by EPMA measurements, light grey: three phase fields determined by analysis of the neighboring two phase fields, dotted black lines: tie-lines measured by EPMA.

The solubility of Al and Cu in the binary phases is noticeable higher than at 500 °C. The phase γ1 is stable up to the composition Al13Cu76Si11. The binary phase (Al,Cu)-β was not found in any of the ternary samples. In contrast, the binary phase (Cu,Si)-κ shows a continuous solubility extending almost to the binary Al–Cu system. The phases η, ɛ and γ show a solubility of 2, 3 and 5 at.% Al, respectively.

EPMA analyses of samples in the region between (Al,Cu)-γ1 and (Cu,Si)-γ indicate an additional phase with a composition between Al4Cu81Si15 and Al10Cu78.5Si11.5. Powder XRD analysis of this phase show a very well crystallized structure not known in the limiting binary phase diagrams. A sample with the nominal composition Al12Cu77Si11 shows (Cu,Si)-κ and the unknown phase, referred to as τ from now on, in equilibrium at 700 °C. The powder XRD pattern of the sample is shown in Fig. 4. A piece of this sample was re-annealed at 500 °C for three weeks. Powder XRD analysis of this piece shows ɛ, γ1 and κ in equilibrium. The pattern of τ completely disappeared. In the isothermal section at 700 °C, the three phase fields {ɛ + γ + τ} and {γ + κ + τ} are present at the Cu-rich side of the phase τ. At the Cu-poor side of the phase, the phase fields {γ1 + κ + τ} and {ɛ + γ1 + τ} are present (see Fig. 3). Combining these three phase fields and the decomposition of the sample Al12Cu77Si11, two invariant reactions can be suggested between 700 and 500 °C: γ + τ = ɛ + κ followed by τ = ɛ + γ1 + κ. A sample with the nominal composition of Al10Cu77Si13, located in the three phase field {ɛ + γ1 + κ} was annealed at 500 °C and subsequently investigated by DTA. It did not show any thermal effect in the region between 500 and 700 °C. The lack of a thermal effect can be interpreted either by the fact that the heat exchange during the invariant reaction τ = ɛ + γ1 + κ is too small to be detected by DTA analysis, or that it is too slow to occur at a heating rate of 5 K min−1 at all. Nevertheless, the annealing results indicate that a ternary compound τ is formed in the ternary system between 500 and 700 °C. This contradicts previous authors [38] who do not indicate a ternary compound in the system Al–Cu–Si. Determination of the crystal structure of τ will be attempted by the authors in the near future.

Fig. 4.

Powder XRD pattern of a sample with the nominal composition of Al12Cu77Si11 annealed at 700 °C. Note that the diffractogram was recorded in the 2θ-range between 10 and 120°, but is only shown between 35 and 80°2θ for the sake of clarity of representation.

Considering the measured tie-lines and the XRD analysis of the respective samples listed in Table 2, the remaining three phase fields present at 700 °C are: {ɛ + γ1 + η} and {(Cu) + γ1 + κ} as indicated in Fig. 3.

Powder XRD analysis of samples with their nominal composition in the vicinity of Al20Cu78Si2 show several very broad peaks which can not be derived from any neighboring structure. The most intense peaks are at 26.2, 27.2, 44.9 and 46.2°2θ. A sample with the nominal composition Al20Cu78Si2 annealed at 700 °C shows (Cu) and the additional peaks. After re-annealing of the sample at 500 °C, (Cu) and κ are present, but the additional peaks mentioned before are still present with considerable intensity (see Fig. 5). As cast samples in this region reach equilibrium without this phase at 500 °C after 3 weeks of annealing. A sample with the nominal composition Al25Cu72.5Si2.5 shows the three phase field {(Cu) + γ1 + κ} after annealing at 500 °C. This may in indicate a ternary compound which is stable at 700 °C but the annealing time at 500 °C (3 weeks) was not enough to re-establish the equilibrium at 500 °C. EPMA analysis of samples showing the additional peaks do not indicate an additional phase. Contrary to the peaks assigned to τ in Fig. 3, the possible ternary phase in this region does not crystallize very well, making it very difficult to determine its structure. It should be pointed out, that this particular part of the phase diagram is in conflict with earlier interpretations. On the one hand, the assessed phase diagram by Lukas and Lebrun [37] assumes a complete solid solubility between the W-type β-phases of Cu–Si and Al–Cu, on the other hand our results at 700 °C do not show any significant solubility of Si in (Al,Cu)-β, a very extended (Cu,Si)-κ phase field, and a possible ternary phase very close to binary (Al,Cu)-β. This area definitely needs additional investigations at high temperatures to clarify phase equilibria and crystal structures.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the powder XRD pattern of a sample with the nominal composition Al20Cu78Si2, annealed at 700 °C (bottom) and re-annealed at 500 °C (top). Note that the diffractograms were recorded in the 2θ-range between 10 and 120°, but are only shown between 34 and 56°2θ for the sake of clarity of representation.

3.3. Isopleths and ternary reaction scheme

Since the transitions ɛ1–ɛ2 and γ0–γ1 in the binary system Al–Cu were determined to be of higher order [3,4], the distinction between the high temperature phases ɛ1 and γ0 and the low temperature phase ɛ2 and γ1 in the reaction scheme is not appropriate. Therefore the respective phases will be designated as ɛ1,2 and γ0,1 in the following section.

The isopleth at 40 at.% Si is shown in Fig. 6. Continuous horizontal lines indicate reactions determined by invariant effects in DTA measurements. Dashed horizontal lines indicate solid state reactions which have to be present due to adjacent invariant reactions and participating three phase fields, but were not determined experimentally. An overview of the determined and estimated invariant reactions including the reaction temperatures as well as the estimated composition of the participating phases is given in Table 3. Some solid state reactions at approximately 25 at.% Al were not determined by thermal analysis of samples in this isopleth but by samples in the isopleth at 10 at.% Si (see below). The invariant reactions determined in the Al-rich part of the isopleth are well determined and in good agreement with the limiting binary system Al–Cu [4]. In the Cu-rich part of the isopleth, some inconsistencies remain. Samples between 4 and 8.5 at.% Al show extremely weak non-invariant effects around 512 °C which could not be assigned to any reaction. The sample with the nominal composition Cu60Si40 shows two peaks with low and equal intensity at the onset temperatures 546 and 555 °C. Despite the fact that there are two distinct peaks, they can only be assigned to the reaction η = η′ + (Si) in the binary Cu–Si system.

Fig. 6.

Isopleth at 40 at.% Cu. Circles: invariant reactions, diamonds: non-invariant reactions, triangles up: liquidus on heating, triangles down: liquidus on cooling.

Table 3.

Invariant reactions in the system Al–Cu–Si and the estimated composition of the reactants.

| Reaction | T/°C | Phase | Composition/at.% |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | Cu | Si | |||

| Max: L = γ0,1 + Si | 778 | L | 27.0 | 57.0 | 16.0 |

| γ0,1 | 26.0 | 72.0. | 2.0 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| U1: L + γ0,1 = ɛ1,2 + Si | 747 | L | 37.0 | 50.0 | 13.0 |

| γ0,1 | 36.0 | 62.5 | 1.5 | ||

| ɛ1,2 | 40.0 | 59.5 | 0.5 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| U2: L + γ0,1 = δ + Si | 740 | L | 13.5 | 66.0 | 20.5 |

| γ0,1 | 21.0 | 72.5 | 6.5 | ||

| δ | 15.5 | 73.5 | 11.0 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| E1: L = δ + η + Si | 730 | L | 11.0 | 68.0 | 21.0 |

| δ | 15.0 | 72.0 | 13.0 | ||

| η | 2.0 | 75.0 | 23.0 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| U3: δ + Si = γ0,1 + η | 579 < T < 730 | δ | 14.0 | 75.0 | 11.0 |

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| γ0,1 | 21.5 | 71.5 | 7.0 | ||

| η | 2.0 | 76.0 | 22.0 | ||

| U4: ɛ1,2 + γ0,1 = δ + Si | 679 | ɛ1,2 | 40.0 | 59.5 | 0.5 |

| γ0,1 | 36.0 | 62.5 | 1.5 | ||

| δ | 38.5 | 61.0 | 0.5 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| U5: γ + τ = ɛ + κ | 500 < T < 700 | γ | 5.0 | 80.0 | 15.0 |

| τ | 6.0 | 79.0 | 15.0 | ||

| ɛ | 2.0 | 78.0 | 20.0 | ||

| κ | 8.0 | 81.0 | 11.0 | ||

| U6: L + ɛ1,2 = η1 + Si | 603 | L | 60.0 | 32.0 | 8.0 |

| ɛ1,2 | 42.5 | 57.0 | 0.5 | ||

| η1 | 48.5 | 51.0 | 0.5 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| U7: ɛ1,2 + η1 = Si + ζ2 | 599 | ɛ1,2 | 42.0 | 57.5 | 0.5 |

| η1 | 47.5 | 52.0 | 0.5 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| ζ2 | 44.5 | 55.0 | 0.5 | ||

| U8: ɛ + η = γ0,1 + η′ | 583 | ɛ | 2.0 | 78.0 | 20.0 |

| η | 2.0 | 75.5 | 22.5 | ||

| γ0,1 | 24.5 | 70.0 | 5.5 | ||

| η′ | 1.5 | 76.0 | 22.5 | ||

| U9: η1 + ζ2 = η2 + Si | 579 | η1 | 47.5 | 52.0 | 0.5 |

| ζ2 | 45.0 | 54.5 | 0.5 | ||

| η2 | 46.0 | 53.5 | 0.5 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| U10: L + η1 = Si + θ | 573 | L | 67.0 | 26.5 | 6.5 |

| η1 | 48.5 | 51.0 | 0.5 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| θ | 67.0 | 32.0 | 1.0 | ||

| E2: τ = ɛ + γ0,1 + κ | 500 < T < 700 | τ | 10.5 | 77.0 | 12.5 |

| ɛ | 2.5 | 77.5 | 20.0 | ||

| γ0,1 | 18.0 | 74.0 | 8.0 | ||

| κ | 11.0 | 80.0 | 9.0 | ||

| E4: η1 = Si + η2 + θ | 500 < T < 573 | η1 | 48.0 | 51.5 | 0.5 |

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| η2 | 48.5 | 50.5 | 1.0 | ||

| θ | 66.5 | 32.5 | 1.0 | ||

| U11: η + γ0,1 = η′ + Si | 579 | η | 2.0 | 75.0 | 23.0 |

| γ0,1 | 24.0 | 70.0 | 6.0 | ||

| η′ | 2.5 | 75.0 | 22.5 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| P1: ɛ + η′ + γ0,1 = η″ | 570 < T < 583 | ɛ | 2.0 | 78.0 | 20.0 |

| η′ | 1.5 | 76.0 | 22.5 | ||

| γ0,1 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 6.0 | ||

| η″ | 2.0 | 75.5 | 22.5 | ||

| E3: ɛ1,2 = δ + Si + ζ2 | 570 | ɛ1,2 | 42.0 | 57.5 | 0.5 |

| δ | 40.0 | 59.5 | 0.5 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| ζ2 | 44.0 | 55.5 | 0.5 | ||

| U12: δ + ζ2 = Si + ζ1 | 557 | δ | 40.0 | 59.5 | 0.5 |

| ζ2 | 44.0 | 55.5 | 0.5 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| ζ1 | 43.0 | 56.5 | 0.5 | ||

| U13: η′ + γ0,1 = η″ + Si | 550 | η′ | 1.5 | 76.0 | 22.5 |

| γ0,1 | 24.5 | 69.0 | 6.5 | ||

| η″ | 2.0 | 76.0 | 22.0 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| U14: Si + ζ2 = η2 + ζ1 | 500 < T < 558 | Si | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| ζ2 | 44.5 | 55.0 | 0.5 | ||

| η2 | 45.0 | 54.0 | 1.0 | ||

| ζ1 | 43.0 | 56.5 | 0.5 | ||

| U15: ɛ + γ0,1 = η″ + κ | 400 < T < 500 | ɛ | 2.0 | 78.0 | 20.0 |

| γ0,1 | 18.0 | 72.5 | 9.5 | ||

| η″ | 2.5 | 76.0 | 21.5 | ||

| κ | 14.0 | 78.0 | 8.0 | ||

| E4: L = Al + Si + θ | 522 | L | 80.5 | 13.5 | 6.0 |

| Al | 96.0 | 2.5 | 1.5 | ||

| Si | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| θ | 68.0 | 31.0 | 1.0 | ||

The isopleth shown in Fig. 6 matches the isothermal sections experimentally determined in this work at 500 and 700 °C as well as the isothermal section at 400 °C published by Lukas and Lebrun [37]. The high solubility of Al in the low temperature phase Cu3Si-η″ compared to the solubility of Al in the high temperature phases Cu3Si-η′ and Cu3Si-η is originated in the isothermal section at 400 °C. In accordance with the liquidus projection surface published by Lukas and Lebrun [37], (Si) primarily crystallizes over the whole composition range.

The isopleth at 10 at.% Si is shown in Fig. 7. The Al-rich part down to approx. 20 at.% Al shows the same reactions like in the 40 at.% Si isopleth. Due to the low Si-content in the isopleth, the primary crystallization fields are different, however (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Isopleth at 10 at.% Cu. Circles: invariant reactions, diamonds: non-invariant reactions, triangles up: liquidus on heating, triangles down: liquidus on cooling.

The Cu-rich part of the isopleth shows a more complicated situation. The high solubility ranges of the binary compounds in this region as well as the thermal stabilization of (Cu,Si)-κ and the existence of the ternary phase τ provide a complex sequence of two- and three phase fields stable at 500 and 700 °C. The boundaries of the phase fields corresponding to the isothermal sections are drawn by continuous lines in Fig. 7 in the respective temperature range. Comparison of the three phase fields present at 400, 500 and 700 °C shows that several solid state reactions occur in this region, but only two of them were determined experimentally: U11 at 579 °C and E2 at 663 °C (see Table 3). It was not possible to determine the reaction temperatures of the invariant reactions U15: ɛ + γ0,1 = η″ + κ, P2: ɛ + η′ + γ0,1 = η and U3: δ + Si = γ0,1 + η.

Above 700 °C, the Cu-rich part of the isopleth shows a high number of thermal effects but it was not possible to construct the isopleth and reaction scheme in this region. Additional reliable information on phase equilibria at higher temperature in this region is needed solve this part of the isopleth.

A partial ternary reaction scheme (Scheil diagram) is shown in Fig. 8. The fundament of this diagram is the reaction scheme given by Lukas and Lebrun [37]. New data on the limiting binary systems [4,25] as well as experimental results obtained in the current work were integrated in the reaction scheme. Several invariant reactions indicated by dotted lines were not determined experimentally in this work, but are required due to the existence of neighboring invariant reactions and three phase fields. Missing parts of the reaction scheme are indicated by question marks.

Fig. 8.

Partial reaction scheme (Scheil diagram) for the Al–Cu–Si system. Dashed invariant reaction: temperature not determined experimentally. Open ends with question marks indicate missing parts of the reaction scheme.

4. Conclusions

The largest part of the Al–Cu–Si system, in particular the isothermal phase equilibria at 400 and 500 °C and the reaction sequence in the Cu-poor part of the system, is now well characterized. However, in spite of the numerous experimental studies performed by different authors, phase equilibria in the complex Cu-rich part of the system at higher temperatures are still questionable and require additional attention. The current study revealed the existence of a previously unknown ternary high-temperature compound, whose structure has not been solved up to now. Its equilibria with the liquid phase have to be investigated and the phase relations of the extended solid solutions of κ and β at high temperatures should be subject of additional investigations. Our results at 700 °C raise some doubts regarding the complete solid solubility of the β-phase of Al–Cu and Cu–Si proposed previously, so an independent study of the liquidus projection including extended primary crystallization studies would be favorable. Last but not least, most of the proposed solid state reactions in this area are not accessible by DTA investigations and further annealing studies would be helpful to confirm these and to better fix the respective reaction temperatures.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Austrian Science Found FWF for supporting this work under the project number P19305. Additionally the authors want to thank Theordoros Ntaflos and Franz Kiraly from the Department of Lithospheric Sciences at the University of Vienna for their support in EPMA measurements.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.09.076.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Pan X.M., Lin C., Morral J.E., Brody H.D. An assessment of thermodynamic data for the liquid phase in the Al-rich corner of the Al–Cu–Si system and its application to the solidification of a 319 alloy. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2005;26:225–233. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray J.L. The aluminium–copper system. Inst. Met. Rev. 1985;30:211–233. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu X.J., Ohnuma I., Kainuma R., Ishida K. Phase equilibria in the Cu-rich portion of the Cu–Al binary system. J. Alloys Compd. 1998;264:201–208. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponweiser N., Lengauer C.L., Richter K.W. Re-investigation of phase equilibria in the system Al–Cu and structural analysis of the high-temperature phase eta1-Al(1−delta)Cu. Intermetallics. 2011;19:1737–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.intermet.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riani P., Arrighi L., Marazza R., Mazzone D., Zanicchi G., Ferro R. Ternary rare-earth aluminum systems with copper: a review and a contribution to their assessment. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2004;25:22–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friauf J.B. The crystal structure of two intermetallic compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1927;49:3107–3114. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goedecke T., Sommer F. Solidification behavior of the Al2Cu phase. Z. Metallk. 1996;87:581–586. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preston G.D. An X-ray investigation of some copper–aluminum alloys. Philos. Mag. 1931;12:980–993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley A.J., Goldschmidt H.J., Lipson H. The intermediate phases in the aluminium–copper system after slow cooling. J. Inst. Met. 1938;63:149–162. [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Boragy M., Szepan R., Schubert K. Crystal structure of Cu3Al2+(h) and CuAl(r) J. Less-Common Met. 1972;29:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong C., Zhang Q.H., Wang D.H., Wang Y.M. Al–Cu approximants in the Al3Cu4 alloy. Eur. Phys. J. B. 1998;6:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong C., Zhang Q.H., Wang D.H., Wang Y.M. Al–Cu approximants and associated B2 chemical-twinning modes. Micron. 2000;31:507–514. doi: 10.1016/s0968-4328(99)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulay L.D., Harbrecht B. The crystal structure of zeta(1)-Al3Cu4. J. Alloys Compd. 2004;367:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulay L.D., Harbrecht B. The crystal structure of zeta(2)-Al3Cu4-delta. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2003;629:463–466. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stockdale D. The aluminium–copper alloys of intermediate composition. J. Inst. Met. 1924;31:275–294. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kisi E.H., Browne J.D. Ordering and structural vacancies in nonstoichiometric Cu–Al gamma brasses. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 1991;47:835–843. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnberg L., Westman S. Crystal perfection in a non-centrosymmetric alloy – refinement and test of twinning of gamma-Cu9Al4 structure. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 1978;34:399–404. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hisatsune C. Constitution diagram of the copper–silicon–aluminium system. Mem. Coll. Eng. Kyoto Imp. Univ. 1936;9:18–47. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hisatsune C. The constitution of alloys of copper, aluminum and silicon. I. The equilibrium diagrams of three binary systems. Tetsu to Hagane. 1935;21:726–742. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawson A.G. J. Inst. Met. 1937;61:197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adorno A.T., Guerreiro M.R., Benedetti A.V. Thermal behavior of Cu–Al alloys near the alpha-Cu–Al solubility limit. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2001;65:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray J.L., McAlister A.J. The Al–Si (aluminum–silicon) system. Bull. Alloy Phase Diagr. 1984;5:74–84. 89-90. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olesinski R.W., Abbaschian G.J. The copper–silicon system. Bull. Alloy Phase Diagr. 1986;7:170–178. 193-176. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan X.Y., Chang Y.A. A thermodynamic analysis of the Cu–Si system. J. Alloys Compd. 2000;308:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sufryd K., Ponweiser N., Riani P., Richter K.W., Cacciamani G. Experimental investigation of the Cu–Si phase diagram at x(Cu) > 0.72. Intermetallics. 2011;19:1479–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.intermet.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solberg J.K. Crystal–structure of Eta-Cu3Si precipitates in silicon. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 1978;34:684–698. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukherje K.P., Bandyopadhyaya J.P., Gupta K.P. Phase relationship and crystal structure of intermediate phases in Cu–Si system in composition range of 17 at Pct Si to 25 at Pct Si. Trans. Metall. Soc. AIME. 1969;245:2335–2338. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen C.-Y., Spaepen F. In situ electron microscopy of the phases of Cu3Si. Philos. Mag. 2007;87:5581–5599. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mattern N., Seyrich R., Wilde L., Baehtz C., Knapp M., Acker J. Phase formation of rapidly quenched Cu–Si alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2007;429:211–215. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arrhenius S., Westgren A. X-radiation analysis of copper–silicon alloys. Z. Phys. Chem. 1931;14:66–79. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veer F.A., Burgers W.G., Burgers W.G. Diffusion in the Cu3Si phase of the copper–silicon system. Trans. Am. Inst. Min. Metall. Pet. Eng. 1968;242:669–673. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward W.J., Carroll K.M. Diffusion of copper in the copper–silicon system. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1982;129:227–229. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chromik R.R., Neils W.K., Cotts E.J. Thermodynamic and kinetic study of solid state reactions in the Cu–Si system. J. Appl. Phys. 1999;86:4273–4281. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chromik R.R., Neils W.K., Cotts E.J. Erratum: “Thermodynamic and kinetic study of solid state reactions in the Cu–Si system” [J. Appl. Phys. 86, 4273 (1999)] J. Appl. Phys. 2000;87:U3. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riani P., Sufryd K., Cacciamani G. About the Al–Cu–Si isothermal section at 500 °C and the stability of the epsilon.-Cu15Si4 phase. Intermetallics. 2009;17:154–164. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuyama K. Ternary diagram of the Al–Cu–Si system. Kinzuko no Kenkyu. 1934;11:461–490. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lukas H.L., Lebrun N. Al–Cu–Si (aluminium–copper–silicon) In: Effenberg G., Ilyenko S., editors. Materials – The Landolt-Börnstein Database. Springer; 2005. pp. 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 38.He C.-Y., Du Y., Chen H.-L., Xu H. Experimental investigation and thermodynamic modeling of the Al–Cu–Si system. Calphad. 2009;33:200–210. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wen C.-Y., Spaepen F. Filling the voids in silicon single crystals by precipitation of Cu3Si. Philos. Mag. 2007;87:5565–5579. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miettinen J. Thermodynamic description of the Cu–Al–Si system in the copper-rich corner. Calphad. 2007;31:449–456. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cziple F., Frunzaverde D., Nedelcu D., Padurean I. Thermodynamic characterization of regular solutions in the Al–Cu–Si system. Metalurgia (Bucharest, Rom.) 2008:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanibolotsky D.S., Bieloborodova O.A., Stukalo V.A., Kotova N.V., Lisnyak V.V. Thermodynamics of liquid aluminium–copper–silicon alloys. Thermochim. Acta. 2004;412:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witusiewicz V.T., Arpshofen I., Seifert H.J., Aldinger F. Enthalpy of mixing of liquid Al–Cu–Si alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2000;297:176–184. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshikawa T., Morita K. Thermodynamics of solid silicon equilibrated with Si–Al–Cu liquid alloys. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2005;66:261–265. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruker A.X.S. Users's Manual. Bruker AXS; Karlsruhe, Germany: 2005. TOPAS V3: general profile and structure analysis software for powder diffraction data. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.