Abstract

Hydrogenation of π-unsaturated reactants in the presence of carbonyl compounds or imines promotes reductive C-C coupling, providing a byproduct-free alternative to stoichiometric organometallic reagents in an ever-increasing range of C=X (X = O, NR) additions. Under transfer hydrogenation conditions, hydrogen exchange between alcohols and π-unsaturated reactants triggers generation of electrophile-nucleophile pairs, enabling carbonyl addition directly from the alcohol oxidation level, bypassing discrete alcohol oxidation and generation of stoichiometric byproducts.

1. Introduction

A principal characteristic of a “process-relevant” method is the ability to transform abundant, renewable feedstocks to value-added products in the absence of stoichiometric byproducts.1 This characteristic is embodied by catalytic hydrogenation,2 which has found broad use across all segments of the chemical industry, including the manufacture of chiral pharmaceutical ingredients on scale.3 Similarly, alkene hydroformylation,4 which may be viewed as the prototypical C-C bond forming hydrogenation, combines basic feedstocks (synthesis gas and α-olefins) with complete atom-economy to produce aldehydes.5,6 Presently, hydroformylation ranks as the largest volume application of homogenous metal catalysis.

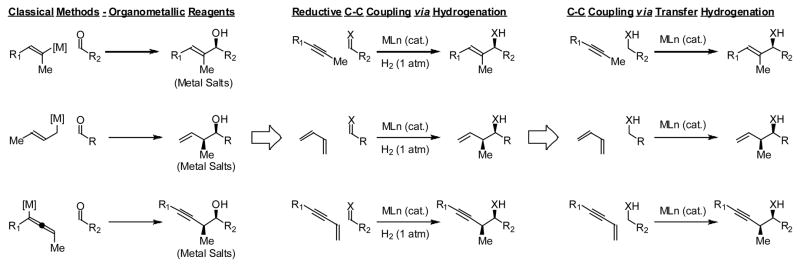

Given the broad impact of hydrogenation and hydroformylation on chemical manufacture, a systematic effort to discover hydrogen-mediated C-C bond formations beyond hydroformylation was undertaken in our laboratory.7,8,9 Remarkably, it was found that hydrogenation of π-unsaturated reactants in the presence of carbonyl compounds or imines promotes reductive C-C coupling, providing an alternative to stoichiometric organometallic reagents in a range of C=X (X = O, NR) additions. Further, under transfer hydrogenation conditions, hydrogen exchange between alcohols and π-unsaturated reactants was found to trigger generation of electrophile-nucleophile pairs, enabling carbonyl addition directly from the alcohol oxidation level, bypassing discrete alcohol oxidation10 and generation of stoichiometric byproducts (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Hydrogen-mediated C-C bond formations beyond hydroformylation.

In this account, a concise overview of enantioselective C-C bond forming hydrogenations and transfer hydrogenations is provided. This account is not exhaustive, but is meant to survey functional group interconversions with attention to processes of greatest potential synthetic utility. More detailed discussion of mechanism and stereochemistry are provided in the primary literature, and individual topics encompassed in this review are presented in several recent monographs.7

2. C-C Bond Forming Hydrogenation

Despite its routine use for well over a century, alkene hydroformylation and the parent Fischer-Tropsch process remained the only examples of hydrogen-mediated reductive coupling at the onset of our studies.4–6 Hence, it became necessary to identify a mechanistic pathway that would unlock hydrogenation for C-C bond formation. Whereas neutral rhodium complexes engage in rapid hydrogen oxidative addition,11 hydrogen oxidative addition is turnover limiting for cationic rhodium catalysts.12,13 Thus, using cationic complexes of rhodium, it was found that the diminished rate of hydrogen oxidative addition and the availability of an additional coordination site conspire to promote oxidative coupling to form metallacyclic intermediates, which are subject to hydrogenolysis to form products of reductive C-C bond formation in the absence of byproducts (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Cationic rhodium complexes promote hydrogen-mediated reductive coupling via oxidative coupling pathways.

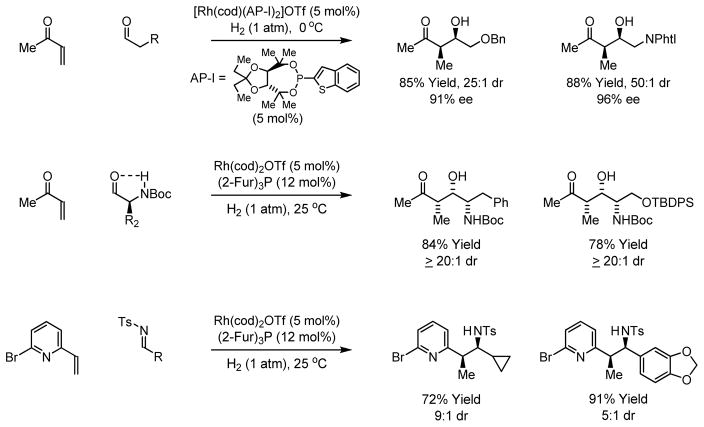

Through the implementation of oxidative coupling pathways, numerous C-C bond forming hydrogenations were developed. For example, hydrogenation of enones in the presence of aldehydes employing a cationic rhodium catalyst modified by a TADDOL-like phosphonite ligand delivers products of reductive aldol addition with high levels of relative and absolute stereocontrol.14 Similarly, high levels of substrate directed asymmetric induction are achieved in hydrogen-mediated reductive aldol additions to N-Boc-α-amino aldehydes.15 Notably, due to the configurational instability of N-Boc-α-amino aldehydes, corresponding additions of alkali enolates are unknown. This reactivity pattern is applicable to other activated olefins, as demonstrated by hydrogen-mediated coupling of 2-vinylpyridines and N-arylsulfonyl imines to furnish branched products of imine addition.16 In each case, syn-diastereoselectivity is observed, as the adjacent substituents about the metallacyclic intermediate prefer a trans-orientation (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Hydrogenation of activated olefins to form products of C-C bond formation.

Hydrogenation of alkynes in the presence of carbonyl and imine partners provides allylic alcohols and allylic amines, respectively, in the absence of stoichiometric byproducts. For example, hydrogenation of acetylenic aldehydes employing a cationic rhodium catalyst induces reductive cyclization to form enantiomerically enriched heterocycles.17 Using cationic iridium catalysts, hydrogenation of 1,2-dialkyl substituted alkynes in the presence of N-arylsulfonyl imines provides trisubstituted allylic amines.18 For both processes, complete levels of E:Z selectivity (≥95:5) are observed. Such alkyne-C=X (X = O, NR) reductive couplings bypass use of preformed vinylmetal reagents (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Intra- and intermolecular hydrogen-mediated C-C coupling of unactivated alkynes.

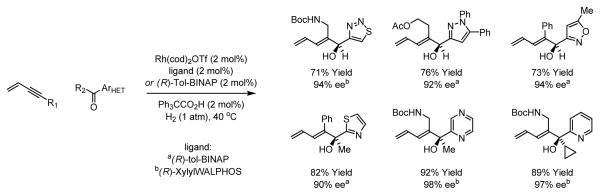

Underscoring functional group compatibility, conjugated enynes participate in reductive couplings to diverse heterocyclic aromatic aldehydes and ketones to provide heteroaryl substituted secondary and tertiary carbinols, respectively. Using rhodium catalysts modified by (R)-tol-BINAP or (R)-xylyl-WALPHOS, uniformly high levels of enantioselectivity are observed. Manipulation of the diene moiety of the coupling products allows access to a variety of functional group arrays (Scheme 5).19

Scheme 5.

Hydrogen-mediated couplings of 1,3-enynes with heterocyclic aromatic aldehydes or ketones.

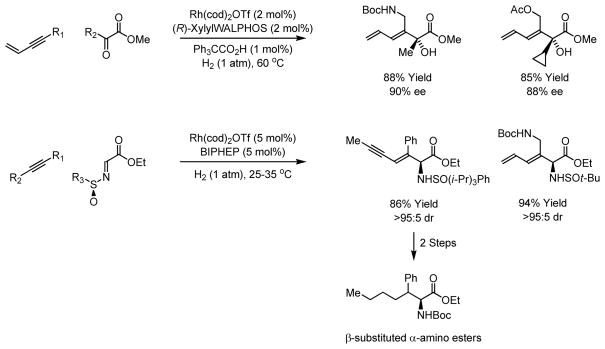

Using cationic rhodium catalysts, hydrogenation of conjugated alkynes in the presence of glyoxalates and pyruvates provides the corresponding α-hydroxy esters with high levels of enantiomeric enrichment.20 Conjugated enynes and diynes also participate in reductive couplings to (N-sulfinyl)iminoacetates under the conditions of rhodium catalyzed hydrogenation.21 Using an appropriately substituted N-sulfinyl substituent,22 the corresponding β, γ-unsaturated α-amino acid esters are generated as single diastereomers. Exhaustive hydrogenation of the diene or enyne side chain of the C-C coupling product provides access to β-substituted α-amino acids (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Formation of α-hydroxy esters and α-amino esters via C-C bond forming hydrogenation.

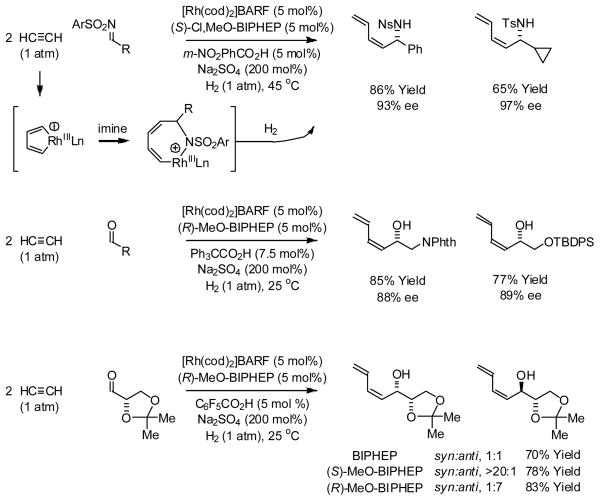

The hydrogen-mediated reductive coupling of acetylene in the presence of carbonyl and imine partners provides products of (Z)-butadienylation.23 As corroborated by isotopic labeling, ESI-MS and computational studies,24 the reaction occurs through an unusual mechanism involving formation of a rhodacyclopentadiene25 followed by C=X (X = O, NR) insertion and hydrogenolysis of the seven-membered metallacycle. Using chirally modified cationic rhodium catalysts, allylic alcohols and allylic amines are formed in highly optically enriched form. Hydrogenative coupling of acetylene to α-chiral aldehydes using enantiomeric rhodium catalysts ligated by (S)-MeO-BIPHEP and (R)-MeO-BIPHEP provides adducts with good levels of catalyst directed diastereoselectivity. This process was used in a formal synthesis of all eight L-hexoses (Scheme 7).23c

Scheme 7.

Rhodium catalyzed hydrogenation of acetylene in the presence of carbonyl and imine partners.

3. C-C Bond Forming Transfer Hydrogenation

Under transfer hydrogenation conditions using ortho-cyclometallated iridium catalysts generated in situ from allyl acetate, 3-nitrobenzoic acid and a chiral bis-phosphine ligand, enantioselective carbonyl allylation is achieved from the alcohol or aldehyde oxidation level using allyl acetate as the allyl donor.26 Aliphatic, allylic and benzylic alcohols are transformed to the corresponding homoallylic alcohols with uniformly high levels of enantioselectivity. In the presence of isopropanol, but under otherwise identical conditions, aldehydes are converted to an equivalent set of adducts. This protocol circumvents cryogenic conditions and the stoichiometric use of metallic reagents or reductants (Scheme 8).

Scheme 8.

Enantioselective iridium catalyzed carbonyl allylation from the alcohol or aldehyde oxidation level.

The cyclometallated iridium π-allyl C,O-benzoate complexes, which have been characterized by single crystal X-ray diffraction, are sufficiently robust that they may be purified chromatographically. Even more remarkable, these complexes may be recovered from reaction mixtures by conventional silica gel chromatography and recycled multiple times without any decline in performance. This capability is established in highly enantioselective reactions of aliphatic, allylic and benzylic alcohols under microwave conditions in aqueous organic media.27 While chromatographic recycling is certainly not feasible on scale, the stability displayed by the catalyst augers well for distillative product removal as in hydroformylation and immobilization of the catalyst (Scheme 9).

Scheme 9.

Chromatographic recovery and recycling of the iridium catalyst in enantioselective carbonyl allylations from the alcohol oxidation level.

A catalytic mechanism consistent with the collective data begins with protonolysis of the iridium π-allyl complex by the reactant alcohol to furnish a pentacoordinate iridium alkoxide. β-Hydride elimination produces aldehyde and an iridium hydride, which deprotonates to generate an anionic iridium(I) intermediate. Oxidative addition of allyl acetate provides the π-allyl complex. Because the π-allyl complex is the catalyst resting state, it can be chromatographically recovered from the reaction mixture. Turnover-limiting aldehyde addition provides an iridium alkoxide. This hexacoordinate 18-electron complex is resistant to β-hydride elimination due to coordination of the homoallylic olefin. Exchange of the homoallylic iridium alkoxide with reactant alcohol releases the product and regenerates the pentacoordinate iridium alkoxide to close the catalytic cycle (Scheme 10).

Scheme 10.

Catalytic mechanism for iridium catalyzed carbonyl allylation under transfer hydrogenation conditions.

Corresponding carbonyl crotylations employing α-methyl allyl acetate can be conducted using the iridium C,O-benzoate complex that is assembled in situ from [Ir(cod)Cl]2, allyl acetate, 4-cyano-3-nitrobenzoic acid and the chiral phosphine ligand (S)-SEGPHOS.28a However, although in situ assembly of the catalyst is convenient and excellent enantioselectivities typically were observed (>95% ee), only modest levels of anti-diastereoselectivity were evident (5:1 – 11:1 dr). Use of the chromatographically purified catalyst allows the reaction to be performed at lower temperature (60 °C), resulting in enhanced levels of anti-diastereo- and enantioselectivity (Scheme 11).28b

Scheme 11.

Enantioselective iridium catalyzed carbonyl crotylation from the alcohol or aldehyde oxidation level.

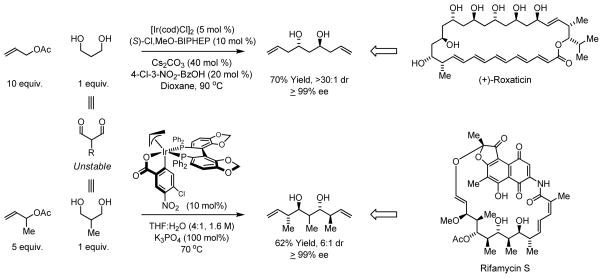

Enantioselective carbonyl allylation and crotylation from the alcohol oxidation level enables carbonyl allylation processes that are not possible using conventional allylmetal and crotylmetal reagents. For example, although 1,3-dialdehydes are intractable and cannot be used in enantioselective double allylation,29 1,3-propanediols are stable and engage in efficient two-directional allylation to provide C2-symmetric adducts.30 In these processes, the minor enantiomer of the mono-allylated intermediate is transformed to the meso-diastereoisomer, thereby amplifying levels of enantioselectivity.31 Through iterative two-directional chain elongation of 1,3-propanediol, a total synthesis of the oxo-polyene macrolide (+)-roxaticin was achieved in 20 steps.32 Corresponding double crotylations of 2-methyl-1,3-propanediol result in the generation of pseudo-C2-symmetric polypropionate stereoquintets, which appear as substructures in diverse polyketide natural products. Using the chromatographically isolated iridium catalyst modified by (R)-SEGPHOS, 1 of 16 possible stereoisomers is formed predominantly.33 This methodology was used to form the C19-C27 ansa chain of rifamycin S in 8 steps (originally prepared in 26 steps), constituting a formal synthesis of the natural product (Scheme 12).34

Scheme 12.

Enantioselective double allylation and double crotylation of 1,3-propanediols to form polyacetate and polypropionate building blocks.

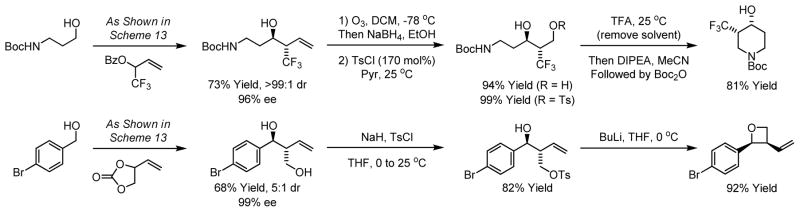

Beyond carbonyl allylation and crotylation, other types of enantioselective allylations are promoted by ortho-cyclometallated iridium catalysts, including α-(trimethylsilyl)allylation,35a α-(hydroxymethyl)allylation35b α-(trifluoromethyl)allylation35c and α-(hydroxy)allylation.35d In each case, enantioselective carbonyl addition is achieved in the absence of stoichiometric metallic reagents (Scheme 13).

Scheme 13.

Enantioselective double and polypropionate building blocks.

The products of allylation are readily transformed to enantiomerically enriched heterocycles that would otherwise be difficult to prepare. For example, diastereo- and enantioselective α-(trifluoromethyl)allylation of N-Boc-aminopropanol enables a four step synthesis of the indicated piperidine.35c A three step synthesis of cis-2,3-disubstituted oxetanes is achieved through carbonyl α-(hydroxy)allylation from the alcohol oxidation level (Scheme 14).35d

Scheme 14.

Synthesis of enantiomerically enriched heterocycles using transfer hydrogenative allylation.

The appearance of iridium hydrides in the catalytic mechanism (Scheme 10), suggests the feasibility of recruiting allenes and dienes as allyl donors via hydrometallation. Indeed, cyclometallated iridium C,O-benzoates modified by (S)-SEGPHOS promote enantioselective carbonyl tert-prenylation from the alcohol or aldehyde oxidation level under exceptionally mild conditions (30–50 °C).36 For reactions conducted from the alcohol oxidation level, stoichiometric byproducts are completely absent. Interestingly, the absolute stereochemistry of tert-prenylation is opposite to that observed in the aforementioned allylations (Scheme 15).

Scheme 15.

Enantioselective carbonyl tert-prenylation from the alcohol or aldehyde oxidation level.

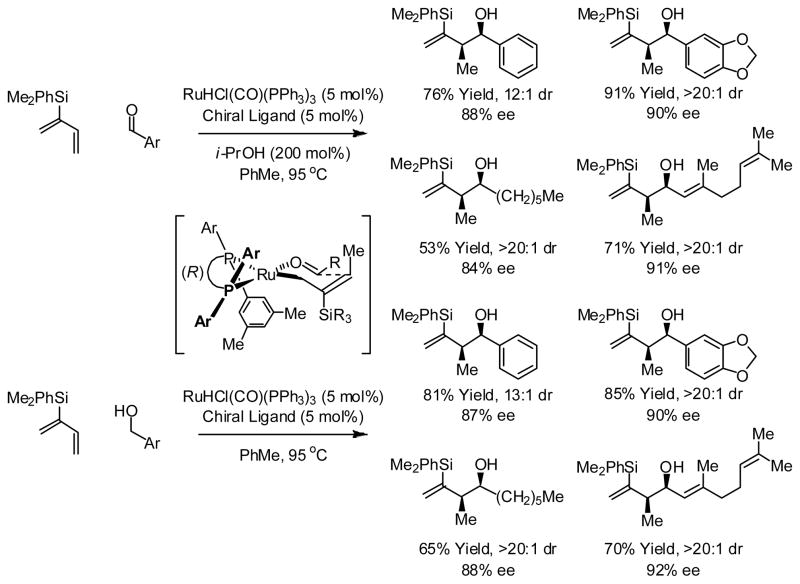

Finally, transfer hydrogenation catalysts based on ruthenium also promote carbonyl addition from the alcohol or aldehyde oxidation level. For example, using chiral ruthenium catalysts modified by (R)-SEGPHOS or (R)-DM-SEGPHOS, the indicated silyl-substituted butadiene, which is prepared in a single manipulation from chloroprene, engages in syn-diastereo- and enantioselective carbonyl crotylation from the alcohol or aldehyde oxidation level.37 Here, to address the issue of relative stereocontrol, the silyl-substituent directs formation of geometrically defined σ-allylruthenium intermediates, which react stereospecifically through closed, chair-like transition structures (Scheme 16).

Scheme 16.

Enantioselective syn-diastereo- and enantioselective carbonyl crotylation from the alcohol or aldehyde oxidation level via ruthenium catalyzed transfer hydrogenation.

4. Conclusion

While numerous first-generation methods for chemical synthesis exist, very little of this methodology is amenable to large volume application. Inspired by the process-relevance of hydrogenation and hydroformylation, we have developed a broad, new family of enantioselective C-C bond forming hydrogenation and transfer hydrogenations. The atom-economy exhibited by these transformations, particularly the exclusion of stoichiometric metallic byproducts, suggests these methods would be viable candidates for use at the process level upon minimization of catalyst loading. The reactivity embodied by these processes evokes numerous possibilities in terms of related transformations, including imine addition from the amine oxidation and the direct C-C coupling of α-olefins. These topics are currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment is made to the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-0038), the NIH-NIGMS (RO1-GM069445), Eli Lilly and Company, Merck, Johnson and Johnson, Firmenich, Umicore, Takasago and the ACS-GCI, for partial support of the research described in this account.

References

- 1.For selected reviews, see: Butters M, Catterick D, Craig A, Curzons A, Dale D, Gillmore A, Green SP, Marziano I, Sherlock JP, White W. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3002. doi: 10.1021/cr050982w.Sheldon RA. Green Chem. 2007;9:1273.Beller M. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2008;110:789. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200600267.

- 2.Sabatier P, Senderens JB. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 1897;124:1358.Sabatier P, Senderens JB. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 1899;128:1173.Sabatier P, Senderens JB. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 1901;132:210.For a biographical sketch of Paul Sabatier, see: Lattes A. C R Acad Sci Ser IIc: Chem. 2000;3:705.

- 3.For selected reviews, see: Hawkins JM, Watson TJN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3224. doi: 10.1002/anie.200330072.Thommen M. Spec Chem Mag. 2005;25:26.Thayer AM. Chem Eng News. 2005;83:40.Jäkel C, Paciello R. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2912. doi: 10.1021/cr040675a.Farina V, Reeves JT, Senanayake CH, Song JJ. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2734. doi: 10.1021/cr040700c.Carey JS, Laffan D, Thomson C, Williams MT. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:2337. doi: 10.1039/b602413k.Constable DJC, Dunn PJ, Hayler JD, Humphrey GR, Leazer JL, Jr, Linderman RJ, Lorenz K, Manley J, Pearlman BA, Wells A, Zaks A, Zhang TY. Green Chem. 2007;9:411.Blaser HU, Pugin B, Spindler F, Thommen M. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:1240. doi: 10.1021/ar7001057.

- 4.Roelen O. Chemische Verwertungsgesellschaft mbH, Oberhausen. German Patent DE. 1938;849:548. [Google Scholar]; Chem Abstr. 1944;38:5501. [Google Scholar]

- 5.For selected reviews on alkene hydroformylation, see: Beller M, Cornils B, Frohning CD, Kohlpaintner CW. J Mol Catal A. 1995;104:17.Frohning CD, Kohlpaintner CW, Bohnen H-W. Carbon Monoxide and Synthesis Gas Chemistry. In: Cornils B, Herrmann WA, editors. Applied Homogeneous Catalysis with Organometallic Compounds. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 1996. pp. 29–104.van Leeuwen PWNM, Claver C, editors. Rhodium Catalyzed Hydroformylation. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Norwell, MA: 2000. Breit B, Seiche W. Synthesis. 2001:1–36.Weissermel K, Arpe H-J. Synthesis involving Carbon Monoxide. Industrial Organic Chemistry. 4. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2003. pp. 127–144.van Leeuwen PWNM. Homogeneous Catalysis: Understanding the Art. Kluwer; Dordrecht: 2004.

- 6.Hydroformylation is an outgrowth of the Fischer-Tropsch process, which represents another key hydrogen-mediated C-C bond formation: Fischer F, Tropsch H. Brennstoff-Chem. 1923;4:276.Fischer F, Tropsch H. Chem Ber. 1923;56B:2428.

- 7.For recent reviews on C-C bond forming hydrogenation and transfer hydrogenation, see: Ngai MY, Kong JR, Krische MJ. J Org Chem. 2007;72:1063. doi: 10.1021/jo061895m.Skucas E, Ngai MY, Komanduri V, Krische MJ. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:1394. doi: 10.1021/ar7001123.Iida H, Krische MJ. Top Curr Chem. 2007;279:77.Shibahara F, Krische MJ. Chem Lett. 2008;37:1102. doi: 10.1246/cl.2008.1102.Han SB, Hassan A, Krische MJ. Synthesis. 2008:2669. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067220.Bower JF, Kim IS, Patman RL, Krische MJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:34. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802938.Han SB, Kim IS, Krische MJ. Chem Commun. 2009:7278. doi: 10.1039/b917243m.Bower JF, Krische MJ. Top Organomet Chem. 2011;43:107. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-15334-1_5.

- 8.Prior to our systematic studies, two isolated reports of hydrogenative C-C coupling were reported in the literature: Molander GA, Hoberg JO. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:3123.Kokubo K, Miura M, Nomura M. Organometallics. 1995;14:4521.

- 9.Side products of reductive C-C bond formation have been observed in catalytic hydrogenation on rare occasions: Moyes RB, Walker DW, Wells PB, Whan DA, Irvine EA. Mechanism of Ethyne Hydrogenation in the Region of the Kinetic Discontinuity: Comparison of C4 Products. In: Dines TJ, Rochester CH, Thomson J, editors. Catalysis and Surface Characterisation (Special Publication) Vol. 114. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge: 1992. pp. 207–212.Bianchini C, Meli A, Peruzzini M, Vizza F, Zanobini F, Frediani P. Organometallics. 1989;8:2080.

- 10.Alcohol oxidation on scale is considered problematic. For reviews, see: Dugger RW, Ragan JA, Brown Ripin DH. Org Proc Res Dev. 2005;9:253.Carey JS, Laffan D, Thomson C, Williams MT. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:2337. doi: 10.1039/b602413k.Caron S, Dugger RW, Gut Ruggeri S, Ragan JA, Brown Ripin DH. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2943. doi: 10.1021/cr040679f.

- 11.For mechanistic studies on alkene hydrogenation catalyzed by neutral Rh(I) complexes, see: Tolman CA, Meakin PZ, Lindner DL, Jesson JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:2762.Halpern J, Wong CS. Chem Commun. 1973:629.Halpern J, Okamoto T, Zakhariev A. J Mol Catal. 1976;2:65.

- 12.For mechanistic studies on the hydrogenation of dehydroamino acids catalyzed by cationic Rh(I) complexes, see: Landis CR, Halpern J. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:1746.Chan ASC, Halpern J. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:838.Halpern J, Riley DP, Chan ASC, Pluth JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:8055.Halpern J. Science. 1982;217:401. doi: 10.1126/science.217.4558.401.

- 13.For reviews encompassing the mechanism of asymmetric hydrogenation catalyzed by cationic rhodium complexes, see: Halpern J. Asymm Synth. 1985;5:41.Landis CR, Brauch TW. Inorg Chim Acta. 1998;270:285.

- 14.Bee C, Han SB, Hassan A, Iida H, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2746. doi: 10.1021/ja710862u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung CK, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:17051. doi: 10.1021/ja066198q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komanduri V, Grant CD, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12592. doi: 10.1021/ja805056g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhee JU, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10674. doi: 10.1021/ja0637954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Barchuk A, Ngai MY, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:8432. doi: 10.1021/ja073018j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ngai MY, Barchuk A, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12644. doi: 10.1021/ja075438e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komanduri V, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16448. doi: 10.1021/ja0673027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Kong JR, Ngai M-Y, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:718. doi: 10.1021/ja056474l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cho CW, Krische MJ. Org Lett. 2006;8:3873. doi: 10.1021/ol061485k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hong YT, Cho CW, Skucas E, Krische MJ. Org Lett. 2007;9:3745. doi: 10.1021/ol7015548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kong JR, Cho CW, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11269. doi: 10.1021/ja051104i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.For reviews on the use of N-tert-butanesulfinyl imines in asymmetric synthesis, see: Davis F, Chen BC. Chem Soc Rev. 1998;27:13.Ellman JA, Owens TD, Tang TP. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:984. doi: 10.1021/ar020066u.Zhou P, Chen BC, Davis F. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:8003.

- 23.(a) Kong JR, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16040. doi: 10.1021/ja0664786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Skucas E, Kong JR, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7242. doi: 10.1021/ja0715896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Han SB, Kong JR, Krische MJ. Org Lett. 2008;10:4133. doi: 10.1021/ol8018874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams VM, Kong JR, Ko BJ, Mantri Y, Brodbelt JS, Baik MH, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16054. doi: 10.1021/ja906225n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bianchini C, Caulton KG, Chardon C, Eisenstein O, Folting K, Johnson TJ, Meli A, Peruzzini M, Rauscher DJ, Streib WE, Vizza F. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5127. and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Kim IS, Ngai M-Y, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6340. doi: 10.1021/ja802001b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim IS, Ngai MY, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14891. doi: 10.1021/ja805722e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao X, Krische MJ. Manuscript in Preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Kim IS, Han SB, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2514. doi: 10.1021/ja808857w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gao X, Townsend IA, Krische MJ. J Org Chem. 2011;76:2350. doi: 10.1021/jo200068q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.For a review on two-directional chain synthesis, see: Poss CS, Schreiber SL. Acc Chem Res. 1994;27:9.

- 30.Lu Y, Kim IS, Hassan A, Del Valle DJ, Krische MJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:5018. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.This mechanism for enantiomeric enrichment is documented by Eliel and Midland: Kogure T, Eliel EL. J Org Chem. 1984;49:576.Midland MM, Gabriel J. J Org Chem. 1985;50:1143.

- 32.Han SB, Hassan A, Kim I-S, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15559. doi: 10.1021/ja1082798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao X, Han H, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133 doi: 10.1021/ja204570w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rifamycin S: Isolation: Sensi P, Margalith P, Timbal MT. Farmaco, Ed Sci. 1959;14:146.Sensi P, Greco AM, Ballotta R. Antibiot Annual. 1959/1960:262.Total Synthesis: Nagaoka H, Rutsch W, Schmid G, Iio H, Johnson MR, Kishi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:7962.Iio H, Nagaoka H, Kishi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:7965.Kishi Y. Pure Appl Chem. 1981;53:1163.Nagaoka H, Kishi Y. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:3873.

- 35.(a) Han SB, Gao X, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9153. doi: 10.1021/ja103299f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang YJ, Yang JH, Kim SH, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4562. doi: 10.1021/ja100949e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gao X, Zhang YJ, Krische MJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:4173. doi: 10.1002/anie.201008296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Han SB, Han HH, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1760. doi: 10.1021/ja9097675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han SB, Kim IS, Han H, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6916. doi: 10.1021/ja902437k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zbieg JR, Moran J, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:10582. doi: 10.1021/ja2046028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]