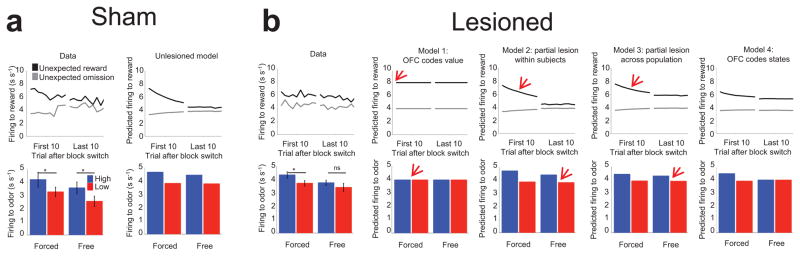

Figure 6. Comparison of model simulations and experimental data.

(a) The unlesioned TDRL model and experimental data from the sham-lesioned rats. Top: At the time of unexpected reward delivery or omission, the model predicts positive (black) and negative (grey) prediction errors whose magnitude diminishes as trials proceed. Bottom: At the time of the odor cue, the model reproduces the increased responding to high value (blue) relative to low value (red) cues on forced trials. Likewise, the model predicts differential firing at the time of decision on free-choice trials. (b) Lesioning the hypothesized OFC component in each model produced qualitatively different effects. Red arrows highlight discrepancies between the models and the experimental data, where these exist. Model 1, which postulates that OFC conveys expected values to dopamine neurons, cannot explain the reduced firing to unexpected rewards at the beginning of a block, nor can it reproduce the differential responding to the two cues on forced-choice trials. Models 2 and 3, which assume a partial lesion of value encoding, cannot account for the lack of significant difference between high and low value choices on free-choice trials in the recorded data, and incorrectly predict significantly diminished responses at the time of reward after learning. Only Model 4, in which OFC encoding enriches the state representation of the task by distinguishing between states based on impending actions, was able to fully account for the results at the time of unexpected reward delivery or omission and at the odor on free- and forced-choice trials.