The crystal structure of the DNA sequence d(CGGGTACCCG)4 as a four-way Holliday junction and its interaction with a calcium ion are described.

Keywords: DNA, four-way junctions, metal–DNA interactions

Abstract

The crystal structure of the decamer sequence d(CGGGTACCCG)4 as a four-way Holliday junction has been determined at 2.35 Å resolution. The sequence was designed in order to understand the principles that govern the relationship between sequence and branching structure. It crystallized as a four-way junction structure with an overall geometry similar to those of previously determined Holliday junction structures.

1. Introduction

The four-way DNA junction, first proposed by Robin Holliday (Holliday, 1964 ▶), plays a key role in cellular processes such as homologous recombination (Nunes-Düby et al., 1987 ▶) and repair of DNA lesions (Dickman et al., 2002 ▶; Déclais et al., 2003 ▶). Single-crystal structures of four-way junctions as DNA-only constructs help in understanding how DNA sequences and other factors affect their inherent structure (Eichman et al., 2002 ▶). All the DNA-only junctions that have been crystallized to date are decanucleotides with a common central trinucleotide motif. They all show the compact antiparallel stacked-X form, in which pairs of duplex arms stack collinearly into nearly continuous double helices (broken only at the crossing point of the junction on the inside strand of each pair).

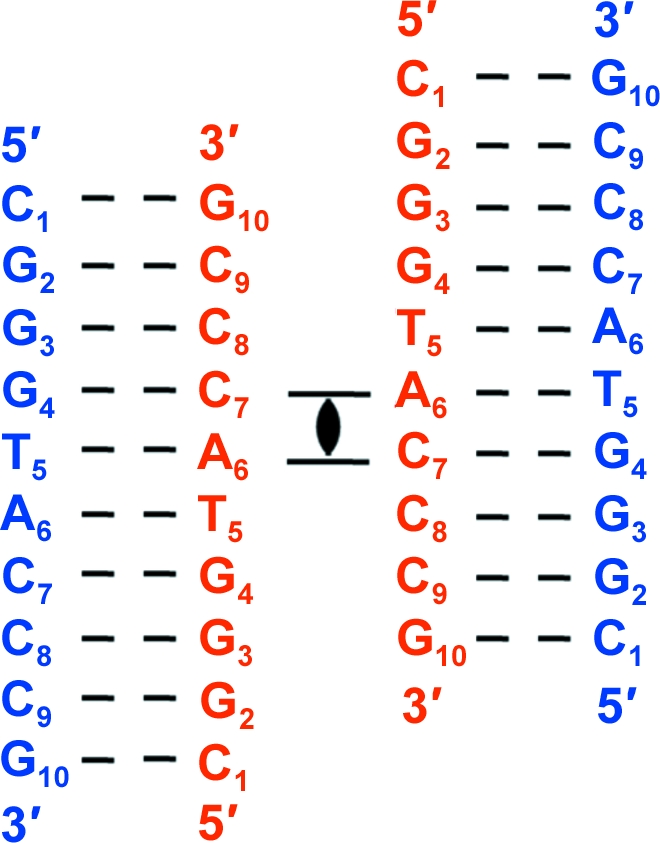

All crystal structures of decanucleotide junctions deposited in the NDB (http://ndbserver.rutgers.edu/; Berman et al., 1992 ▶) contain a cytosine (C2) in the second position and a guanine (G9) in the ninth position flanking the trinucleotide core (in the invert repeat). In the current sequence the pyrimidine C2 is replaced by a purine G2, and the purine G9 is replaced by a pyrimidine C9 (in the invert repeat). Fig. 1 ▶ represents the topology and numbering scheme of the present sequence. The trinucleotide core is not disturbed. The sequence crystallized as a four-way junction with right-handed B-type helical arms.

Figure 1.

Sequence topology of the d(CGGGTACCCG) junction. The four-stranded antiparallel stacked-X Holliday junction is generated by applying the crystallographic twofold symmetry to the two unique strands. Strands are numbered from 1 to 10 in the 5′ to 3′ direction, with the crossing strands coloured red and the noncrossing strands coloured blue.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Crystallization, X-ray diffraction data collection and data processing

PAGE-purified DNA oligonucleotides and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Chemicals Pvt. Ltd (Bangalore, India). Crystals were grown by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method at 293 K from a drop consisting of 1.00 µl 1 mM DNA, 0.80 µl 50 mM sodium cacodylate trihydrate buffer pH 7.0, 0.85 µl 100 mM CaCl2. The hanging drop was equilibrated against a reservoir solution comprised of 300 µl 30% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD). Thin diamond-shaped plate crystals of dimensions 0.18 × 0.10 × 0.03 mm were obtained after six weeks. For data collection at 100 K, the crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. The mother liquor was sufficient for cryoprotection. Diffraction data (Table 1 ▶) were collected in-house at the G. N. Ramachandran X-Ray Facility using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) generated by a Microstar rotating-anode X-ray generator (Bruker AXS) operated at 45 kV and 60 mA. The diffraction images were recorded using a MAR 345 image-plate detector (MAR Research). Data processing was performed using automar (MAR Research GmbH, Germany) and the crystal was found to belong to the monoclinic space group C2, with unit-cell parameters a = 65.29, b = 23.60, c = 37.12 Å, β = 111.30°.

Table 1. Summary of data-processing and refinement statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the last shell.

| Diffraction data | |

| Resolution (Å) | 34.59–2.35 (2.43–2.35) |

| Space group | C2 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 65.29, b = 23.60, c = 37.12, β = 111.30 |

| Rmerge (%) | 11.5 (29.5) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 3.7 (1.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.8 (96.4) |

| Multiplicity | 2.83 (3.29) |

| No. of observations | 6510 |

| No. of unique reflections | 2236 |

| Refinement | |

| No. of DNA atoms | 404 |

| No. of solvent atoms | 18 |

| R factor (%) | 23.34 |

| Rfree (%) | 28.18 |

| R.m.s.d. bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 |

| R.m.s.d. bond angles (°) | 1.980 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | 31.5 |

| PDB entry | 3t8p |

2.2. Structure determination and refinement

The structure was solved by molecular replacement. Since the unit-cell parameters and space group were similar to those of previously determined structures of the four-way junction (Ortiz-Lombardía et al., 1999 ▶; Eichman et al., 2000 ▶), it was decided to first try the four-way junction as the initial model. Thus, a search model was constructed using two strands of the Holliday junction d(CCGGTACCGG) (PDB entry 1nt8, with the appropriate changes made to the sequence at positions 2 and 9; C. J. Cardin, B. C. Gale, J. H. Thorpe, S. C. M. Texieira, Y. Gan, M. I. A. A. Moraes & A. L. Brogden, unpublished work). One of these strands is called the ‘crossing’ strand and the other is called the ‘noncrossing’ strand. (The complete junction is generated by the crystallographic twofold-symmetry axis that passes through the centre of the molecule.) Molecular replacement was carried out using the program AMoRe (Navaza, 1994 ▶) from the CCP4 suite (Winn et al., 2011 ▶) and a solution with a correlation coefficient of 0.64 and an R factor of 0.45 was obtained.

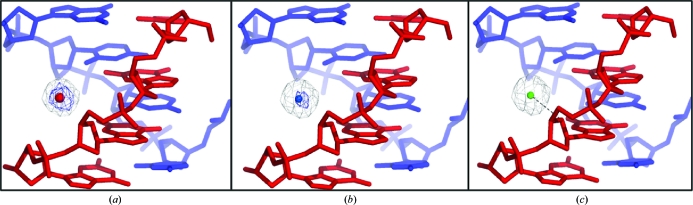

The structure was refined using REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▶) with maximum-likelihood targets and the REFMAC5 dictionary (Vagin et al., 2004 ▶). After initial refinement, a positive peak was visible at the 5σ level in the difference Fourier map. In the positive peak, a fully occupied water molecule was first placed in the density. However, after refinement the difference Fourier map showed the presence of positive electron density at 3σ (B factor = 25.8 Å2; Fig. 2 ▶ a). The same process was next carried out with a fully occupied sodium ion (putatively from the sodium cacodylate trihydrate buffer). After refinement, this also showed positive density in the difference Fourier map at 4σ (B factor = 33.8 Å2; Fig. 2 ▶ b). Finally, refinement of a fully occupied calcium ion at this position did not show any density in the difference Fourier map (B factor = 43.2 Å2; Fig. 2 ▶ c). On the basis of peak height and refinement to a reasonable B factor, we justify the assignment of this positive peak as a Ca2+ ion. We next attempted refinement with a rigid Ca2+ cluster with six coordinated waters around the ion. The refinement did not proceed well, with high R factors, negative electron density and steric clashes. In the asymmetric unit, a total of 18 water molecules were added at various stages of the refinement, each time ensuring that the electron density in the (F o − F c) map (and in subsequent maps), as well as the temperature factors in the subsequent cycles of refinement, warranted the addition. We could not locate the water molecules in the coordination shell around the calcium ion, presumably owing to the limited resolution of the data set. The data-collection and final refinement statistics are given in Table 1 ▶. Graphical analyses of the model and the electron-density maps were carried out using Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▶). Structural analysis and geometrical calculations were carried out using X3DNA (Lu & Olson, 2003 ▶). PyMOL was used to prepare the figures (DeLano, 2002 ▶). The coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the PDB (Berman et al., 2000 ▶) with PDB code 3t8p.

Figure 2.

Ca2+-binding site: the short arm comprising C11 to G14 of the noncrossing strand (blue) base-paired with C7 to G10 of the other crossing strand (red) is shown. The (2F o − F c) Fourier map (light grey) and (F o − F c) difference Fourier map (blue) are contoured at the 1σ and 3σ levels, respectively. (a) A water molecule (red sphere) shows positive density in the difference Fourier map at 3.5σ. (b) An Na+ ion (blue sphere) shows positive density in the difference Fourier map at 4.2σ. (c) A Ca2+ ion (green sphere) shows no positive density in the difference Fourier map and is bound to sugar hydroxyl O4′ of G13 (represented by the black dashed line) on the minor-groove side.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Overall structure

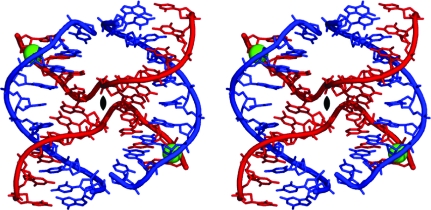

As seen in Fig. 3 ▶, the decamer sequence crystallizes as a four-stranded Holliday junction in a compact right-handed antiparallel stacked-X form (Ortiz-Lombardía et al., 1999 ▶; Eichman et al., 2000 ▶). Four decamer strands form four short helices or arms: (i) two long arms, each six base pairs in length (C1 to A6 of one noncrossing strand paired with G10 to T5 of one crossing strand), and (ii) two short arms, each four base pairs in length (pairing C7 to G10 of the noncrossing strand with G4 to C1 of an alternative crossing strand). These short helices stack in pairs to form two semi-continuous ten-base-pair double helices joined at the ‘hip’ by the two crossing strands. The two double helices are related by a crystallographic twofold axis. The crystal structure is isomorphous to those obtained previously and will be interpreted by comparisons between the present structure (abbreviated ACCc), the ‘reference’ structure (abbreviated ACC) and other previously reported structures. Table 2 ▶ gives the root-mean-square deviations (r.m.s.d.s) in atomic positions after least-squares superposition of the present structure and other relevant junction structures on the ‘reference’ ACC structure. It is clear from these that in the present structure the changes in the sequence do not lead to any gross deviation from the ACC structure either in molecular conformation or in crystal packing.

Figure 3.

Stereoview of the atomic structure of d(CGGGTACCCG)4. Chemical bonds in the structure are rendered as sticks and the paths of the phosphodeoxyribose backbones are traced as solid ribbons. Ca2+ ions are shown as green spheres. The ‘crossing’ strands are shown in red and the ‘noncrossing’ strands are shown in blue.

Table 2. Root-mean-square deviations (Å) of crystal structures of selected junctions superposed with the present structure and reference structure (ACC).

| Sequence and abbreviation | ACC | gACC | GCC | ATC | ACBr5U | ACCc | PDB code and reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d(CCGGTACCGG)4 (ACC) | 0.0 | 1dcw; Eichman et al. (2000 ▶) | |||||

| d(CCGGGACCGG)4 (gACC) | 1.3 | 0.0 | 467d; Ortiz-Lombardía et al. (1999 ▶) | ||||

| d(CCGGCGCCGG)4 (GCC) | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1p4y; Hays, Watson et al. (2003 ▶) | |||

| d(CCGATATCGG)4 (ATC) | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 1zf3; Hays et al. (2005 ▶) | ||

| d(CCAGTACBr5UGG)4 (ACBr5U) | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 1p54; Hays, Vargason et al. (2003 ▶) | |

| d(CGGGTACCCG)4 (ACCc) | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 3t8p; this work |

Thus, we have determined the single-crystal structure of a new sequence d(C1G2G3G4T5A6C7C8C9G10)4 as a four-stranded Holliday junction in which the sequence has been mutated at the second and ninth position so as to flank the invert-repeat core N6N7N8 with alternating pyrimidine–purine bases. However, the introduction of G2 in place of C2 of the reference junction sequence resulted in no discernible gross deviations in the overall structure of the junction.

3.2. Core interactions

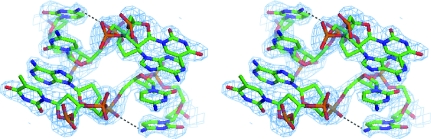

Single-crystal structures of the four-way junctions as DNA-only constructs suggest that a number of interactions are associated with the core sequence, including (i) a direct hydrogen bond between the N4 N atom of the C8 base and the C7 nucleotide phosphate O atom (C8–C7 interaction), (ii) a solvent-mediated interaction between the complementary G3 nucleotide and the A6 nucleotide phosphate O atom (G3–A6 interaction) and (iii) a direct hydrogen bond from the N4 N atom of the C7 base to the A6 phosphate O atom (C7–A6 interaction). The C8–C7 interaction can be partially replaced by an analogous Br⋯O halogen bond, as in the structure of the ACBr5U junction (Hays, Watson et al., 2003 ▶). As shown in Fig. 4 ▶, only one of these core interactions is seen in the present structure of the ACCc junction. This is a direct hydrogen-bonding interaction (2.85 Å) between the amino N4 N atom at the major-groove surface of the cytosine C8 base and the phosphate O atom of C7. This was first identified as helping to stabilize the ACC junction (Ortiz-Lombardía et al., 1999 ▶; Eichman et al., 2000 ▶). The other two core interactions, namely the G3–A6 interaction and C7–A6 interaction, are missing in this structure. The sodium ion seen at the centre of the junction in the ACC structure (Eichman et al., 2000 ▶) is absent in the ACCc junction, suggesting that this ion interaction is not crucial to the overall geometry of the junction (Hays, Vargason et al., 2003 ▶). The separation of the phosphates at the junction crossing is 7.83 Å (P/A6–P/A6*), which is similar to the values seen in other junction structures. The cavity between these phosphates is devoid of sodium ions and water molecules, unlike observed previously (Hays, Vargason et al., 2003 ▶). Consistent with previous junction structures, we find that one of the interactions at the ACC core sequence is conserved throughout this class of DNA structures (Eichman et al., 2000 ▶).

Figure 4.

Stereoview of the electron-density map at the crossover region. The (2F o − F c) map (blue, contoured at 1σ) shows clear separation between the two crossing strands. The atoms are coloured as follows: C atoms, green; O atoms, red; N atoms, blue; P atoms, yellow. The direct hydrogen bonds between N4 of the C8 nucleotide and the phosphate O atom of the C7 nucleotide (C7–C8) core interaction are shown as dashed black lines.

3.3. Junction and helicoidal parameters

Comparison of the junction parameters, namely J roll (160.3°), J twist (41.8°) and J slide (0.00 Å) (Watson et al., 2004 ▶), of the present junction structure with those of other junction structures (Ortiz-Lombardía et al., 1999 ▶; Eichman et al., 2000 ▶; Hays, Vargason et al., 2003 ▶; Hays, Watson et al., 2003 ▶; Hays et al., 2005 ▶) reveals that all the values are close to those seen in other junction structures and in particular to the reference ACC structure. Table 3 ▶ gives the average helical parameters for the two semi-continuous double helices of the ACCc junction. For comparison, the values for the B-DNA fibre model are also given. The average helical twist is 37.8°, with 9.5 base pairs per turn. The average helical rise is 3.46 Å. These values are only slightly different from those in the B-DNA fibre model.

Table 3. Average helical parameters measured using X3DNA for the quasi-continuous helical arms in the four-way junction and comparison with the B-DNA fibre model (Chandrasekaran & Arnott, 1989 ▶).

Minor-groove and major-groove widths were measured as the ‘refined’ phosphate–phosphate distances based on the method proposed by El Hassan & Calladine (1998 ▶) and incorporated in the program X3DNA (Lu & Olson, 2003 ▶).

| d(CGGGTACCCG)4 | B-DNA fibre model | |

|---|---|---|

| Helical rise (Å) | 3.46 | 3.38 |

| Helical twist (°) | 37.8 | 36.0 |

| Roll (°) | 1.6 | 0.0 |

| Tilt (°) | −0.9 | 0.0 |

| Inclination (°) | 1.9 | 2.8 |

| Propeller twist (°) | −15.7 | −15.1 |

| X-displacement (Å) | 2.35 | 0.00 |

| Slide (Å) | 1.62 | 0.00 |

| Major-groove width (Å) | 10.26 | 11.60 |

| Minor-groove width (Å) | 7.03 | 6.00 |

Table 4 ▶ compares the individual helical twist at each base step in the different junction structures. In ACCc the value varies from 22.6° to 50.3°. For the first base step in ACCc, C1pG2:C9pG10, the twist is high (50.3°) when compared with those in other junction structures. At the second base step of ACCc, G2pG3:C8pC9, however, the value is 22.6°, which is lower than in other junction structures. The third base step of ACCc, G3pG4:C7pC8, has a helical twist of 48.8°, which is higher than those obtained for other junctions. This alternation of the helical twist values may be a consequence of the presence of alternating pyrimidine–purine bases in the first three nucleotide positions. The value at the base step A6pC7:G4pT5, where the phosphodeoxyribose backbone departs from the duplex to form the junction crossing, is close to that of the reference ACC structure. Table 5 ▶ gives the values of the backbone torsion angles. The backbone adopts both BI [∊ (C4′—C3′—O3′—P) = trans, ζ (C3′—O3′—P—O5′) = gauche −] and BII (∊ = gauche −, ζ = trans) conformations (Hartmann et al., 1993 ▶). At the crossing, ∊ and ζ assume the gauche − and gauche − conformations, respectively, at the phosphate belonging to A6 of the crossing strand. In other words, a change of about 120° at a single torsion angle is sufficient to change the complementary strand in the duplex to a crossing strand in the junction. All except two of the sugar rings in the crossing strand have C2′-endo puckering, whereas in the noncrossing strand all except three have C2′-endo puckering.

Table 4. Comparison of helical twist (measured using X3DNA; Lu & Olson, 2003 ▶) for the junction structures of d(CCGGTACCGG) (ACC), d(CCGGGACCGG) (gACC), d(CCGGCGCCGG) (GCC), d(CCGATATCGG) (ATC), d(CCAGTACBr5UGG) (ACBr5U) and d(CGGGTACCCG) (ACCc).

Owing to the crystallographic twofold symmetry present in all of the structures, values are shown only for one quasi-continuous decanucleotide helix. In column 1, only the nucleotides common to all sequences are named. Common purines (Pu) or pyrimidines (Py) are also indicated. Others are simply termed ‘nucleotides’ (N). The dinucleotide Pu6pPy7:Pu4pN5 (in bold) is the point where the phosphodeoxyribose backbone departs from the duplex to form the junction crossing.

| Helical twist (°) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence (PDB code) | ACC (1dcw) | gACC (467d) | GCC (1p4y) | ATC (1zf3) | ACBr5U (1p54) | ACCc (3t8p) |

| C1pN2:N9pG10 | 41.3 | 40.3 | 38.1 | 37.3 | 45.5 | 50.3 |

| N2pPu3:Py8pN9 | 37.0 | 42.2 | 35.1 | 43.8 | 45.4 | 22.6 |

| Pu3pPu4:Pu7pPy8 | 41.9 | 33.4 | 40.5 | 35.7 | 34.6 | 48.8 |

| Pu4pN5:Pu6pPy7 | 35.4 | 38.5 | 38.8 | 34.0 | 30.6 | 31.4 |

| N5pPu6:N5pPu6 | 32.5 | 35.4 | 30.0 | 43.8 | 38.4 | 37.2 |

| Pu6pPy7:Pu4pN5 | 35.7 | 25.7 | 32.6 | 27.4 | 33.3 | 36.7 |

| Py7pPy8:Pu3pPu4 | 39.6 | 42.9 | 45.0 | 42.2 | 32.1 | 42.1 |

| Py8pN3:N2pPu3 | 38.9 | 40.6 | 35.1 | 36.7 | 52.3 | 30.4 |

| N9pG10:C1pN2 | 38.2 | 36.1 | 42.8 | 38.9 | 32.9 | 40.8 |

| Average (SD) | 37.8 (3.1) | 37.2 (5.4) | 37.6 (4.8) | 37.8 (5.2) | 38.3 (7.6) | 37.8 (8.9) |

Table 5. Comparison of backbone torsion angles measured using X3DNA (Lu & Olson, 2003 ▶) at the junction crossover in d(CCGGTACCGG) (ACC), d(CCGGGACCGG) (gACC), d(CCGGCGCCGG) (GCC), d(CCGATATCGG) (ATC), d(CCAGTACBr5UGG) (ACBr5U) and d(CGGGTACCCG) (ACCc).

Pu and Py are the residues of the crossing strand.

| Backbone torsion angles† of the sugar–phosphate–sugar junction (°) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC | gACC | GCC | ATC | ACBr5U | ACCc | |

| Pu6 γ | 35.2 | 27.7 | 47.0 | 40.8 | 43.8 | 48.1 |

| Pu6 δ | 142.7 | 137.0 | 133.6 | 146.1 | 145.2 | 132.3 |

| Pu6 ∊ | −89.6 | −73.6 | −77.3 | −97.2 | −89.3 | −87.8 |

| Pu6 ζ | −78.6 | −96.6 | −86.2 | −69.2 | −67.1 | −101.7 |

| Py7 α | −75.0 | −47.0 | −46.9 | −57.4 | −65.8 | −106.9 |

The torsion angles are defined as α, O3′—P—O5′—C5′; γ, O5′—C5′—C4′—C3′; δ, C5′—C4′—C3′—O3′; ∊, C4′—C3′—O3′—P; ζ, C3′—O3′—P—O5′.

3.4. Ion interactions

Metal ions play a key role in junction stabilization, particularly of the junction phosphates. In the case of junctions crystallized using larger cations such as Sr2+ and Ba2+, the cations were found in both the major-groove and minor-groove regions of the stacked duplex arms (PDB entries 3goj, 3gom and 3goo; Hall et al., 2011 ▶; A. Naseer & C. J. Cardin, unpublished work). Keeping in view the in vivo conditions, where invert-repeat sequences are surrounded predominantly by Na+ and Mg2+ ions (Fraústo da Silva & Williams, 2001 ▶), it is essential to check whether the calcium-binding site in the ACCc junction is in fact an Mg2+-binding site.

We observed one Ca2+-binding site situated within the minor groove at the C8·G13/C9·G12 step of the short arm (see Fig. 2 ▶ c). The Ca2+ ion interacts with the sugar O4′ of G13 of the noncrossing strand (Ca—O distance of 3.49 Å). Since the maximum value for a Ca—O bond distance is 2.82 Å, we assume that the Ca2+ ion makes a water-mediated interaction with the sugar O4′. However, the limited resolution of our data set does not allow us to locate the water molecules associated with the ion with precision. Thus, the ion has not been unambiguously assigned. However, the location of the Ca2+ ion in the present structure is similar to that found in the amphimorphic sequence d(CCGATATCGG) when it crystallizes as a junction. [This sequence crystallizes as B-type DNA at low concentrations of cations, whereas it forms a junction structure at higher concentrations (10–20 mM) of Ca2+ (Hays et al., 2005 ▶).] The higher resolution of the latter junction structure (1.84 Å) enhances our confidence in assigning Ca2+ in the present ACCc structure.

Previous reports (Thorpe et al., 2003 ▶) have revealed that the Ca2+-binding site is specific for the CG/CG step (or more generally the CPu/PyG step) in the minor groove. The Ca2+-binding site in the present structure also agrees with theoretical studies which suggest plausible positions for ion binding within four-way junctions using Brownian dynamics calculations (van Buuren et al., 2002 ▶). These studies suggest that the most important binding site for a divalent cation is in the minor groove (van Buuren et al., 2002 ▶). However, Mg2+ is too small and has such a strong preference for octahedral geometry that it is unlikely to prefer this location. Even though the calcium ion in the present structure lies some distance from the defining features of the junction, it could stabilize the junction in its compact stacked-X form by neutralizing the negative potential of the phosphates in this stretch of the DNA helix.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: d(CGGGTACCCG)4, 3t8p

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the following agencies of the Government of India: DBT under a research grant and DST under the FIST programme. PKM and SV thank CSIR for Senior Research Fellowships.

References

- Berman, H. M., Olson, W. K., Beveridge, D. L., Westbrook, J., Gelbin, A., Demeny, T., Hsieh, S. H., Srinivasan, A. R. & Schneider, B. (1992). Biophys. J. 63, 751–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T. N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N. & Bourne, P. E. (2000). Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Buuren, B. N. van, Hermann, T., Wijmenga, S. S. & Westhof, E. (2002). Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 507–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekaran, R. & Arnott, S. (1989). Landolt-Börnstein Numerical Data and Functional Relationships in Science and Technology, Group VII/1b, Nucleic Acids, edited by W. Saenger, pp. 31–170. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Déclais, A. C., Fogg, J. M., Freeman, A. D., Coste, F., Hadden, J. M., Phillips, S. E. & Lilley, D. M. (2003). EMBO J. 22, 1398–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W. L. (2002). PyMOL http://www.pymol.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dickman, M. J., Ingleston, S. M., Sedelnikova, S. E., Rafferty, J. B., Lloyd, R. G., Grasby, J. A. & Hornby, D. P. (2002). Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 5492–5501. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Eichman, B. F., Ortiz-Lombardía, M., Aymamí, J., Coll, M. & Ho, P. S. (2002). J. Mol. Biol. 320, 1037–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Eichman, B. F., Vargason, J. M., Mooers, B. H. & Ho, P. S. (2000). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 3971–3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- El Hassan, M. A. & Calladine, C. R. (1998). J. Mol. Biol. 282, 331–343. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fraústo da Silva, J. J. R. & Williams, R. J. P. (2001). The Biological Chemistry of the Elements: the Inorganic Chemistry of Life, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.

- Hall, J. P., O’Sullivan, K., Naseer, A., Smith, J. A., Kelly, J. M. & Cardin, C. J. (2011). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 17610–17614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, B., Piazzola, D. & Lavery, R. (1993). Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hays, F. A., Teegarden, A., Jones, Z. J., Harms, M., Raup, D., Watson, J., Cavaliere, E. & Ho, P. S. (2005). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 7157–7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hays, F. A., Vargason, J. M. & Ho, P. S. (2003). Biochemistry, 42, 9586–9597. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hays, F. A., Watson, J. & Ho, P. S. (2003). J. Biol. Chem. 278, 49663–49666. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Holliday, R. (1964). Genet. Res. 5, 282–304.

- Lu, X.-J. & Olson, W. K. (2003). Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5108–5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Navaza, J. (1994). Acta Cryst. A50, 157–163.

- Nunes-Düby, S. E., Matsumoto, L. & Landy, A. (1987). Cell, 50, 779–788. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Lombardía, M., González, A., Eritja, R., Aymamí, J., Azorín, F. & Coll, M. (1999). Nature Struct. Biol. 6, 913–917. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, J. H., Gale, B. C., Teixeira, S. C. & Cardin, C. J. (2003). J. Mol. Biol. 327, 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vagin, A. A., Steiner, R. A., Lebedev, A. A., Potterton, L., McNicholas, S., Long, F. & Murshudov, G. N. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2184–2195. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Watson, J., Hays, F. A. & Ho, P. S. (2004). Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 3017–3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: d(CGGGTACCCG)4, 3t8p