Abstract

Background

It has not been clearly established whether second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors actually improve the survival of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase who are given nilotinib or dasatinib therapy after treatment failure with imatinib.

Design and Methods

To address this issue we compared the survival of 104 patients in whom first-line therapy with imatinib failed and who were then treated with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors with the outcome of 246 patients in whom interferon-α therapy failed and who did not receive tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy.

Results

Patients treated with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors had longer overall survival than the interferon controls (adjusted relative risk= 0.28, P=0.0001). However this survival advantage was limited to the 64.4% of patients in whom imatinib failed but who achieved complete cytogenetic response with the subsequent tyrosine kinase inhibitor (adjusted relative risk =0.05, P=0.003), whereas the 35.6% of patients who failed to achieve complete cytogenetic response on the second or third inhibitor had similar overall survival to that of the controls (adjusted relative risk=0.76, P=0.65).

Conclusions

Patients in whom imatinib treatment fails who receive sequential therapy with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors have an enormous advantage in survival over controls (palliative therapy); this advantage is, however, limited to the majority of the patients who achieve a complete cytogenetic response.

Keywords: imatinib failure, chronic myeloid leukemia, second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors, overall survival

Introduction

Imatinib is an extremely effective therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia.1 Patients in chronic phase who achieve an optimal response may expect a normal life expectancy,2 but not all patients achieve an adequate response or can tolerate imatinib. At 5 years approximately 40% of the patients have discontinued imatinib on account of an unsatisfactory response or toxicity.1 Patients in whom imatinib fails are often treated with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as nilotinib or dasatinib. These drugs induce complete cytogenetic responses in approximately 50% of such patients,3–7 but to date it is unclear whether the use of second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors as second- or third-line therapy prolongs the survival of patients in whom imatinib has failed. This lack of evidence has allowed funding agencies in some countries to challenge the use of these drugs.8 In order to address this point we compared the survival of 283 patients who received imatinib as first-line therapy (followed by second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors if imatinib therapy failed) in our institution with the outcome of 246 patients in whom interferon-α therapy had failed in the UK Medical Research Council’s CML-III trial.9

Design and Methods

Patients treated with tyroskine kinase inhibitors

Between June 2000 and September 2009, 283 consecutive adult patients with BCR-ABL-positive chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase received imatinib 400 mg daily as first-line therapy as described elsewhere.1 The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the local Institutional Review Board and patients gave written informed consent to their participation. The median follow up was 67.9 months (range, 14–122). Of the 283 patients, 104 patients required second-line therapy with dasatinib (n=67) or nilotinib (n=37) at some point after imatinib therapy had failed.3 Dasatinib and nilotinib were administered as described elsewhere.3 Twenty-one patients in whom second-line dasatinib or nilotinib failed were treated with the alternative tyrosine kinase inhibitor as previously described.10 Complete, partial and major cytogenetic responses were defined using standard criteria.1

Control patients

Between September 1986 and April 1994, 587 patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase were randomly allocated to receive either interferon-α or chemotherapy (busulfan or hydroxyurea) as maintenance therapy after initial induction treatment with chemotherapy as part of the UK Medical Research Council’s CML-III trial.9 Two hundred and ninety-three patients were allocated to the interferon-α arm, of whom 246 failed to respond to interferon-α at some stage, as described elsewhere.11 Thus data on these 246 patients were eventually used for this study. After satisfying criteria for interferon-α treatment failure 122 (49.6%) patients remained on interferon-α-containing regimens until disease progression, whereas 124 (50.4%) abandoned interferon-α therapy at some stage after its failure; of these, 117 (94.3%) were treated with hydroxyurea and 7 (5.7%) with busulfan. The median follow up was 50.4 months (range, 2–202).

Statistical methods

The probability of overall survival from the time point of diagnosis was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Patients were censored at the time of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (28 and 63 patients in the tyrosine kinase inhibitor and control group, respectively). Univariate analyses to identify prognostic factors for overall survival were carried out using the log-rank test. A Cox regression model of time to death was used to compare the outcome of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor and control groups. In addition to the treatment group the model was adjusted for the independently significant variables shown in Table 1 (age at diagnosis and Sokal risk group). The influence of cytogenetic response on overall survival was studied in a time-dependent Cox model (also adjusted as described above).

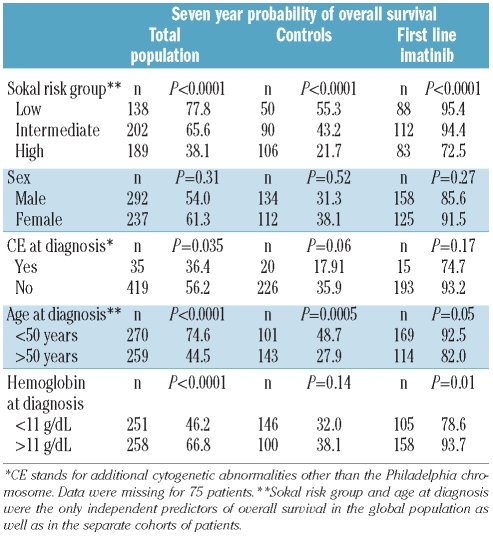

Table 1.

Seven-year probability of overall survival according to the patients’ characteristics.

Results

Improved survival on tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy is limited only to those patients who achieve complete cytogenetic response on first or subsequent line of therapy

Table 1 shows the 7-year probabilities of overall survival according to the characteristics of the patients. Unsurprisingly the overall survival of the 283 patients who received imatinib as first-line therapy was dramatically superior to that of the 246 interferon-α treated controls, (adjusted relative risk=0.11, P<0.0001).

Equally, the 179 (63.2%) patients who achieved and sustained a complete cytogenetic response on first-line imatinib therapy had an even greater advantage in overall survival over the interferon controls (adjusted relative risk=0.02, 95% confidence interval=0.002–0.126, P<0.0001).

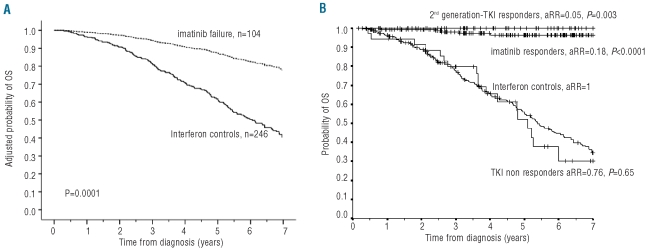

In the remaining 104 (36.8%) patients, imatinib was deemed to have failed at some point (73 had primary cytogenetic resistance, 8 lost their complete cytogenetic response and 23 were imatinib intolerant). These patients had an overall survival longer than that of the control patients in whom interferon treatment had failed (adjusted relative risk=0.28, 95% confidence interval, P=0.0001; Figure 1). Sixty-seven (64.4%) of the 104 patients in whom imatinib had failed achieved complete cytogenetic responses on second- (n=49) or third-line (n=14) therapy with another tyrosine kinase inhibitor. These patients also had a longer overall survival than the interferon controls (adjusted relative risk=0.05, 95% confidence interval=0.007–0.36, P=0.003) and an overall survival similar to that of the patients who responded to imatinib; in contrast the 37 patients who failed to achieve complete cytogenetic response on second- or third-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy had an overall survival similar to that of the control patients (adjusted relative risk=0.76, P=0.65); thus the survival benefit conferred by tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy is limited to the majority of patients who achieve a sustained complete cytogenetic responses either on imatinib or on subsequent tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, while the patients whose imatinib therapy failed and who then did not achieve a complete cytogenetic response with subsequent tyrosine kinase inhibitors had a prognosis similar to that of the control patients in whom interferon therapy failed.

Figure 1.

Adjusted probabilities of survival for patients in whom imatinib failed and for controls (A) and unadjusted probabilities of overall survival (OS) in the different groups of patients (B). Panel (A) shows the adjusted probabilities of overall survival for the 104 patients in whom imatinib treatment failed and the 246 controls in whom interferon treatment failed (adjusted relative risk; aRR = 0.28, 95CI=0.145–0.531, P=0.0001). The unadjusted probabilities of 7-year survival for both groups were 73.4 and 34.4% respectively. Panel (B) shows the unadjusted 7-year probability of overall survival for the 246 interferon controls (34.4%), the 179 patients who achieved and sustained a complete cytogenetic response on imatinib (96.6%), the 67 patients who achieved a complete cytogenetic response on second-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy (100%) and the 37 patients who failed to achieve a satisfactory response on tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy (30.2%). We also show the adjusted relative risk for overall survival with respect the interferon controls, see text.

Partial cytogenetic response does not confer a survival advantage

Fourteen (5.5%) of the 256 patients who achieved a partial cytogenetic response (≤35% Philadelphia chromosome positivity) on tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy (either first-, second-, or third-line) failed to achieve a complete cytogenetic response (i.e. the response did not improve to complete cytogenetic response). These 14 patients had significantly worse overall survival that the 242 patients who eventually achieved complete cytogenetic responses (adjusted relative risk=6.64, 95% confidence interval=1.74–25.4, P=0.006), and an overall survival similar to that of the controls in whom interferon had failed (adjusted relative risk=0.6, P=0.4), indicating that a partial cytogenetic response per se may not be an adequate therapeutic target.

Discussion

The results of observational studies based on historical comparisons, such as the present study, have been regarded by some as intrinsically less reliable than results of randomized prospective studies. There is, however, evidence that the results obtained in well-designed observational studies do not differ from those of randomized trials12,13 and there are circumstances when randomized prospective studies would be impossible to design or indeed unethical.11 Moreover bias is not inevitable in observational studies if the prognostic factors used in the adjustment strongly predict the outcome,14,15 and if physicians are prevented from selecting a preferred therapy, even inadvertently, for the patients with the poorest prognosis.12

Our study appears to satisfy these three conditions: firstly, it is unlikely that a randomized trial involving the type of patients we studied will ever be possible; secondly, the model was adjusted for strongly predictive factors; and thirdly, the clinicians had no opportunity to influence the treatment allocation. In other words, the UK Medical Research Council’s CML-III patients could only continue interferon or switch to palliative treatment since tyrosine kinase inhibitors were not available at the time and all later patients in our catchment area were treated with imatinib.

We used an adjusted Cox model to study a population of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase who received imatinib as first-line therapy, and compared their outcome with that of a population of patients treated originally with interferon-α whose therapy eventually failed but who then continued treatment with interferon-α, hydroxyurea or, occasionally, busulfan. As the outcome of this control population represents the outcome of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with palliative therapy, it is not surprising that imatinib responders had a dramatically better outcome. Patients whose imatinib treatment failed who then received therapy with another tyrosine kinase inhibitor also had an enormous advantage in survival over the controls (adjusted relative risk=0.28, P=0.0001, Figure 1), but we found that this survival advantage was limited only to those patients who achieved complete cytogenetic responses after failed imatinib therapy, while the other patients had a prognosis identical to that of the controls. In other words patients who fail to achieve a complete cytogenetic response did not fare better than if they had been given palliative therapy. It is, therefore, of paramount importance to ensure that patients whose imatinib treatment fails are treated subsequently with at least one other tyrosine kinase inhibitor and, if necessary, preferably with two tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Funding Scheme. We also thank the patients who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Authorship and Disclosures

The information provided by the authors about contributions from persons listed as authors and in acknowledgments is available with the full text of this paper at www.haematologica.org.

Financial and other disclosures provided by the authors using the ICMJE (www.icmje.org) Uniform Format for Disclosure of Competing Interests are also available at www.haematologica.org.

References

- 1.de Lavallade H, Apperley JF, Khorashad JS, Milojkovic D, Reid AG, Bua M, et al. Imatinib for newly diagnosed patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: incidence of sustained responses in an intention-to-treat analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(20):3358–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marin D. Current status of imatinib as frontline therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2010;47(4):312–8. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milojkovic D, Nicholson E, Apperley JF, Holyoake TL, Shepherd P, Drummond MW, et al. Early prediction of success or failure of treatment with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2010;95(2):224–31. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.012781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, Donato N, Nicoll J, Paquette R, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2531–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, Bhalla K, O'Brien S, Wassmann B, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2542–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantarjian HM, Giles FJ, Bhalla KN, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Larson RA, Gattermann N, et al. Nilotinib is effective in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase after imatinib resistance or intolerance: 24-month follow-up results. Blood. 2011;117(4):1141–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-277152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah NP, Kim DW, Kantarjian H, Rousselot P, Llacer PE, Enrico A, et al. Potent, transient inhibition of BCR-ABL with dasatinib 100 mg daily achieves rapid and durable cytogenetic responses and high transformation-free survival rates in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients with resistance, suboptimal response or intolerance to imatinib. Haematologica. 2010;95(2):232–40. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.011452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NICE. Imatinib-resistant, dasatinib and nilotinib for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia. 2011. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=byId&o=13003#keydocs.

- 9.Allan NC, Richards SM, Shepherd PC. UK Medical Research Council randomised, multicentre trial of interferon-alpha n1 for chronic myeloid leukaemia: improved survival irrespective of cytogenetic response. The UK Medical Research Council's Working Parties for Therapeutic Trials in Adult Leukaemia. Lancet. 1995;345(8962):1392–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim AR, Paliompeis C, Bua M, Milojkovic D, Szydlo R, Khorashad JS, et al. Efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) as third-line therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase who have failed 2 prior lines of TKI therapy. Blood. 2010;116(25):5497–500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-291922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marin D, Marktel S, Szydlo R, Klein JP, Bua M, Foot N, et al. Survival of patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukaemia on imatinib after failure on interferon alfa. Lancet. 2003;362(9384):617–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benson K, Hartz AJ. A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(25):1878–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(25):1887–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pocock SJ, Elbourne DR. Randomized trials or observational tribulations? N Engl J Med. 2000;342(25):1907–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips AN, Grabar S, Tassie JM, Costagliola D, Lundgren JD, Egger M. Use of observational databases to evaluate the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: comparison of cohort studies with randomized trials. EuroSIDA, the French Hospital Database on HIV and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study Groups. AIDS. 1999;13(15):2075–82. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910220-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]