Abstract

Treadmill exercise capacity in resting metabolic equivalents (METs) and stress hemodynamic, electrocardiographic (ECG), and myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) responses are independently predictive of adverse clinical events. However, limited data exist for arm ergometer stress testing (AXT) in patients who cannot perform leg exercise because of lower extremity disabilities. We sought to determine the extent to which AXT METs, hemodynamic, ECG, and MPI responses to arm exercise add independent incremental value to demographic and clinical variables for prediction of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), or late coronary revascularization, individually or as a composite. A prospective cohort of 186 patients aged 64 ± 10 (SD) yr, unable to perform lower extremity exercise, underwent AXT MPI for clinical reasons between 1997 and 2002, and were followed for 62 ± 23 mo, to an endpoint of death or 12/31/2006. Average annual rates were 5.4% for mortality, 2.2% for MI, 2.5% for late coronary revascularization, and 8.0% for combined events. After adjustment for age and clinical variables, AXT METs [P < 0.05; hazard ratio (HR) = 0.59; confidence interval (CI) = 0.35–0.84] and abnormal MPI (P < 0.01; HR = 2.48; CI = 2.15–2.81) were independently predictive of mortality. A positive AXT ECG (P < 0.05; HR = 2.61; CI = 2.13–3.10) was predictive of MI. Death and MI combined were prognosticated by METs (P < 0.05; HR = 0.63; CI = 0.41–0.85), MPI (P < 0.05; HR = 1.77; CI = 1.49–2.05), and a positive AXT ECG (P < 0.05; HR = 1.86; CI = 1.55–2.17). In conclusion, for high risk older patients who cannot perform leg exercise because of lower extremity disabilities, AXT METs are as important as MPI for prediction of mortality alone and death and MI combined, and a positive AXT ECG prognosticates MI alone and death and MI combined.

Keywords: mortality, myocardial infarction, survival, nuclear medicine

leg exercise capacity is one of the most robust predictors of all-cause and/or cardiovascular mortality (5, 7, 21, 23, 28). Recently we have demonstrated that arm ergometer exercise (AXT) capacity, hemodynamic and electrocardiographic (ECG) responses also independently prognosticate all-cause mortality and/or subsequent myocardial infarction (MI) in patients who cannot perform lower extremity exercise (15). Studies by other investigators have shown that the severity of myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) abnormalities is greater with AXT plus dipyridamole stress than with pharmacological MPI alone (29) and predictive of anatomic findings at cardiac catheterization (3, 12). However, in contrast to treadmill or leg cycle ergometer MPI stress (13, 20, 25), the relative value of exercise variables and MPI data for prognostication of outcome has not been characterized for AXT, which elicits about 40% lower peak oxygen uptake but greater blood pressure at similar oxygen uptake than treadmill exercise (2, 7). Given the increasingly large number of individuals who cannot perform lower extremity exercise, the valuable prognostic information that may be obtained with AXT ECG testing alone, and the additional time expenditure, cost, and radiation exposure required for scintigraphic stress testing, we sought to evaluate the relative clinical predictive value of exercise and MPI variables in the context of AXT. Thus, the purpose of this investigation was to determine the extent to which AXT capacity, hemodynamic, ECG, and MPI variables add incremental value for prognostication of all-cause mortality, MI, and late coronary revascularization alone or in combination in high risk older patients unable or unwilling to perform lower extremity exercise.

METHODS

Participants.

A total of 186 consecutive patients aged 64 ± 10 yr underwent AXT testing, rest and single photon emission computed tomographic (SPECT) MPI at the St. Louis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (STL VAMC) between November 1997 and November 2002. This population comprised patients who were referred for MPI for clinical reasons but were unable or unwilling to perform treadmill exercise because of lower extremity disabilities. No patients who completed the exercise protocol were excluded but those scheduled for testing and found to have conditions for which stress testing might be contraindicated (7) or who could not complete the protocol were not included. Prior to the procedure, participants were instructed to fast overnight and withhold beta adrenergic blocking agents and one-half of their usual insulin doses on the morning of the test, but to take all other medications. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our institution. All patients provided voluntary written informed consent for the procedure.

MPI protocol.

Upon arrival in the stress testing laboratory, an intravenous line was placed, generally in the antecubital fossa of the nondominant arm. Baseline SPECT imaging was performed in the supine posture 30 min after intravenous administration of 8–10 mCi of Tc-99m sestamibi (30). Following baseline image acquistion, AXT studies were conducted and 22–30 mCi of Tc-99m sestamibi was injected 30–60 s before peak exercise. Baseline and stress imaging acquisitions were carried out with a single-head Siemens Orbitor (Seimens; Hoffman Estates) gamma camera with SPECT imaging in a 180 degree arc with 64 stops at 40 s per stop. A dual-head ADAC Forte (Phillips; Milpitas, CA) gamma camera was employed for SPECT studies conducted after February 2002. Myocardial perfusion image processing was performed with Autoquant software (Phillips). After processing, juxtaposed stress and baseline SPECT images were displayed and interpreted in short, vertical long, and horizontal long axis projections. The studies were determined to be normal or abnormal and perfusion defects were further characterized as large, moderate-sized, or small and fixed, reversible, or mixed, based on semiquantitative visual interpretation. Rest and AXT images were evaluated by STL VAMC board-certified nuclear medicine physicians. For the 20-segment left ventricular model, small defects were defined as having 1–3 abnormal myocardial segments, and moderate-sized and large defects by 4–6, and ≥7 abnormal segments, respectively.

Arm exercise protocol.

Patients exercised in the seated posture with a wall-mounted, electronically braked cycle ergometer (Angio 2000, Lode BV, Groningen, The Netherlands). A progressive, multistage protocol designed to elicit exhaustion or symptoms within 5–12 min was used with constant work increments of 50–200 kilopond-meters (kpm), equivalent to 8.2–32.7 W, every 2 min, depending on pretest estimated exercise capacity (7, 23). The test endpoint was exhaustion except when symptom-limited exercise was terminated for standard criteria (7) or for inability to maintain a cycling cadence of at least 40 rpm (16).

After a brief history and physical examination to ensure clinical stability and identify contraindications to stress testing, a baseline 12-lead ECG was recorded. An ECG was then obtained every minute during AXT, continuously near peak effort, for about 10–15 s thereafter, and every 30–120 s for 6 min postexercise. Blood pressure was determined manually during seated rest and every 3 min during exercise in the nondominant arm while the patient continued cycling with the dominant arm. Blood pressure was also assessed immediately postexercise and every 2 min for 6 min of recovery.

Exercise capacity, heart rate, blood pressure, and ECG analysis.

The AXT protocol was developed based on previous investigations involving AXT in patients with coronary artery disease and congestive heart failure (22). Exercise capacity in resting metabolic equivalents (METs) was determined from the duration of exercise at the peak AXT work rate attained (in kpm), using the standard relationship between oxygen uptake and cycle ergometer work rate. One MET was considered to be equivalent to the resting oxygen uptake of 3.5 ml·kg−1·min−1 and exercise METs = [(2 × kpm) + 300]/[weight (kg) × 3.5] (1).

Peak heart rate in beats per min (bpm) was assessed from the ECG at peak exercise using 3 consecutive QRS complexes in sinus rhythm and an average of 10 consecutive QRS complexes in atrial fibrillation. Peak blood pressure values were those obtained during the time nearest peak effort. Percent age-predicted peak heart rate, delta (peak-resting) heart rate, heart rate rate reserve and peak rate pressure product (PRPP) were calculated using standard definitions (7, 19).

Electrocardiograms were evaluated visually. The criterion for a positive ECG response to exercise was at least 1 mm of flat or down-sloping exercise-induced ST segment deviation (in leads without Q-waves), manifested in at least three consecutive QRS complexes and measured 80 ms after the J-point, exclusive of lead aVR (7). Tracings were considered indeterminate in the presence of left bundle branch block, left ventricular hypertrophy with repolarization abnormalities, ventricular paced QRS complexes, or in ECG leads with baseline ST segment depression greater than 1 mm (7).

Outcome data.

Occurrence and date of death, MI, and late coronary revascularization (either coronary artery bypass surgery or percutaneous intervention) and clinical diagnoses of study participants were determined by review of all VA electronic medical records preceding and following AXT MPI evaluations until the occurrence of death from any cause or 12/31/2006. These records, which included scanned and reported results of non-VA episodes of care, have a mortality ascertainment reliability comparable to the National Death Index (10). The investigators had no knowledge of AXT or MPI results at the time of electronic chart review. The criteria for MI were elevated creatine kinase-MB or troponin above the 99th percentile and either ischemic ECG changes or symptoms. Coronary revascularization within 60 days of AXT was considered to be related to the latter procedure and late revascularization was defined as being >60 days after stress testing. Patients were not censored after MI or coronary revascularization at any time point.

Statistical data analysis.

All calculations were performed with SAS 9.1 (26). Student's t-tests were used to assess for statistically significant differences between group mean values (data expressed as mean ± SD). The associations of demographic, clinical, exercise, and MPI data with all-cause mortality, MI, and late coronary revascularization, individually or in combination, were determined by Cox regression models to evaluate univariate and multivariate statistical significance, hazard ratios (HR), and 95% confidence intervals (CI). For the initial univariate analysis, a proportional hazards model was employed for covariates of age, height, weight, body mass index, the 6 clinical variables listed in Tables 1 and 2, treatment with a beta blocker, rest and exercise heart rate and blood pressure, PRPP, exercise capacity and normal or abnormal ECG and MPI responses to AXT. Statistically significant demographic, clinical, exercise, and MPI variables by univariate analysis also were assessed in a multivariate model based on step-wise selection of independent incrementally significant variables and evaluated by Wald-Chi squared analysis. Kaplan-Meier models were employed to compare survival curves. Sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values of a positive AXT ECG, and MPI variables were calculated using standard definitions (27).

Table 1.

Characteristics of survivors and nonsurvivors

| Total (n = 186) | Survived (n = 134) | Died (n = 52) | Univariate HR (95% CI) | P | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical variables | |||||||

| Age, yr | 64 ± 10 | 62 ± 10 | 68 ± 10 | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | <0.01 | ||

| Height, in. | 69 ± 4 | 70 ± 3 | 69 ± 5 | 0.90 (0.87–0.94) | <0.01 | ||

| Weight, lb | 213 ± 56 | 220 ± 56 | 196 ± 53 | 0.99 (0.99–1.0) | <0.01 | ||

| Body-mass index, kg/m2 | 31 ± 8 | 31 ± 7 | 30 ± 9 | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.14 | ||

| No. of patients (%) | |||||||

| Congestive heart failure | 33 (18%) | 21 (16%) | 12 (23%) | 1.58 (1.25-1.91) | 0.17 | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 100 (54%) | 67 (50%) | 33 (63%) | 1.59 (1.30–1.88) | 0.11 | ||

| Current smoker | 66 (35%) | 47 (35%) | 19 (37%) | 1.07 (0.78–1.36) | 0.82 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 67 (36%) | 46 (34%) | 21 (40%) | 1.23 (0.94–1.51) | 0.47 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 92 (49%) | 70 (52%) | 22 (42%) | 0.77 (0.48–1.05) | 0.34 | ||

| Hypertension | 152 (82%) | 105 (78%) | 47 (90%) | 2.24 (1.77–2.71) | 0.09 | ||

| Beta-blocker | 64 (34%) | 52 (39%) | 12 (23%) | 0.54 (0.21–0.87) | 0.06 | ||

| Arm exercise stress test variables | |||||||

| Resting values | |||||||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 73 ± 14 | 72 ± 15 | 76 ± 13 | 1.02 (1.00-1.03) | 0.05 | ||

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||||||

| Systolic | 133 ± 21 | 133 ± 21 | 133 ± 21 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.90 | ||

| Diastolic | 82 ± 12 | 82 ± 13 | 80 ± 11 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | 0.35 | ||

| Peak exercise | |||||||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 122 ± 22 | 123 ± 21 | 119 ± 22 | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.23 | ||

| Delta heart rate, beats/min | 50 ± 21 | 52 ± 21 | 43 ± 22 | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | <0.01 | ||

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||||||

| Systolic | 164 ± 29 | 167 ± 30 | 159 ± 26 | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.06 | ||

| Diastolic | 94 ± 17 | 94 ± 16 | 93 ± 19 | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.46 | ||

| Peak rate pressure product, beats/min · mmHg · 10−3 | 20 ± 5 | 21 ± 5 | 19 ± 5 | 0.95 (0.92–0.97) | 0.04 | ||

| METs | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 0.51 (0.34–0.69) | <0.01 | 0.59 (0.35–0.84) | 0.04 |

| Electrocardiogram | |||||||

| Positive electrocardiogram | 26 (14%) | 17 (13%) | 9 (17%) | 1.27 (0.90–1.64) | 0.51 | ||

| MPI variables | |||||||

| Abnormal study | 106 (57%) | 66 (49%) | 40 (77%) | 2.83 (2.50–3.16) | <0.01 | 2.48 (2.15–2.81) | <0.01 |

| Defect size | |||||||

| Large | 49 (26%) | 29 (22%) | 20 (38%) | 3.06 (2.69–3.42) | <0.01 | ||

| Moderate | 25 (13%) | 17 (13%) | 8 (15%) | 2.33 (1.87–2.78) | 0.06 | ||

| Small | 32 (17%) | 20 (15%) | 12 (23%) | 2.84 (2.43–3.25) | 0.01 | ||

| Defect type | |||||||

| Fixed | 55 (30%) | 32 (24%) | 23 (44%) | 2.77 (2.45–3.09) | <0.01 | ||

| Mixed | 28 (15%) | 16 (12%) | 12 (23%) | 1.58 (1.27–1.88) | 0.13 | ||

| Reversible | 23 (12%) | 18 (14%) | 5 (10%) | 0.82 (0.34–1.29) | 0.67 | ||

| Transient ischemic dilatation | 4 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (4%) | 2.43 (1.68–3.12) | 0.22 | ||

Values are means ± SD or number of patients and percentages in each group. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging.

Table 2.

Characteristics of death or MI patients vs. event-free survivors

| Total (n = 186) | Event Free (n = 121) | Death or MI (n = 65) | Univariate HR (95% CI) | P | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical variables | |||||||

| Age, yr | 64 ± 10 | 62 ± 10 | 68 ± 10 | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | <0.01 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | 0.05 |

| Height, in. | 69 ± 4 | 70 ± 3 | 69 ± 5 | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | <0.01 | ||

| Weight, lb | 213 ± 56 | 220 ± 56 | 207 ± 61 | 1.00 (0.99–1.0) | 0.18 | ||

| Body-mass index, kg/m2 | 31 ± 8 | 31 ± 7 | 31 ± 10 | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.83 | ||

| No. of patients (%) | |||||||

| Congestive heart failure | 33 (18%) | 18 (15%) | 15 (23%) | 1.57 (1.27–1.86) | 0.13 | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 100 (54%) | 62 (51%) | 38 (58%) | 1.35 (1.10–1.60) | 0.24 | ||

| Current smoker | 66 (35%) | 43 (36%) | 23 (35%) | 0.99 (0.73–1.25) | 0.97 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 67 (36%) | 40 (33%) | 27 (42%) | 1.30 (1.04–1.55) | 0.31 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 92 (49%) | 61 (50%) | 31 (48%) | 0.96 (0.71–1.21) | 0.88 | ||

| Hypertension | 152 (82%) | 93 (77%) | 59 (91%) | 2.54 (2.11–2.97) | 0.03 | 2.88 (2.45–3.31) | 0.01 |

| Beta-blocker | 64 (34%) | 46 (38%) | 18 (28%) | 0.60 (0.30–0.91) | 0.10 | ||

| Arm exercise stress test variables | |||||||

| Resting values | |||||||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 73 ± 14 | 71 ± 15 | 76 ± 13 | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 0.02 | ||

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||||||

| Systolic | 133 ± 21 | 134 ± 20 | 132 ± 22 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.41 | ||

| Diastolic | 82 ± 12 | 82 ± 13 | 80 ± 11 | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.20 | ||

| Peak exercise | |||||||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 122 ± 22 | 123 ± 22 | 120 ± 20 | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.32 | ||

| Delta heart rate, beats/min | 50 ± 21 | 53 ± 21 | 44 ± 21 | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | <0.01 | ||

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||||||

| Systolic | 164 ± 29 | 166 ± 30 | 161 ± 27 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.25 | ||

| Diastolic | 94 ± 17 | 95 ± 15 | 92 ± 19 | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.16 | ||

| Peak rate pressure product, beats/min · mmHg · 10−3 | 20 ± 5 | 21 ± 5 | 19 ± 5 | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.15 | ||

| METs | 3.1 ± .0.9 | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 0.54 (0.39–0.69) | <0.01 | 0.63 (0.41–0.85) | 0.04 |

| Electrocardiogram | |||||||

| Positive electrocardiogram | 26 (14%) | 13 (11%) | 13 (20%) | 1.86 (1.65–2.07) | <0.05 | 1.86 (1.55–2.17) | <0.05 |

| MPI variables | |||||||

| Abnormal study | 106 (57%) | 60 (50%) | 46 (71 %) | 2.15 (1.87–2.42) | <0.01 | 1.77 (1.49–2.05) | 0.04 |

| Defect size | |||||||

| Large | 49 (26%) | 25 (21%) | 24 (37%) | 2.40 (2.09–2.71) | <0.01 | ||

| Moderate | 25 (13%) | 16 (13%) | 9 (14%) | 1.60 (1.19–2.00) | 0.25 | ||

| Small | 32 (17%) | 19 (16%) | 13 (20%) | 2.29 (1.92–2.65) | 0.02 | ||

| Defect type | |||||||

| Fixed | 55 (30%) | 29 (24%) | 26 (40%) | 2.24 (1.95–2.52) | <0.01 | ||

| Mixed | 28 (15%) | 13 (11%) | 15 (23%) | 1.63 (1.36–1.90) | 0.07 | ||

| Reversible | 23 (12%) | 18 (15%) | 5 (8%) | 0.67 (0.20–1.14) | 0.39 | ||

| Transient ischemic dilatation | 4 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 1.81 (1.09–2.52) | 0.41 | ||

Values are means ± SD or number of patients and percentages in each group. MI, myocardial infarction.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics.

Demographic, clinical, and AXT data for all participants as well as survivors, nonsurvivors, and MI-free survivors are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The 186 participants (including 1 woman) were followed for 62 ± 23 mo (median 64 mo). During this interval, there were 52 deaths (28%), 21 MI events (11%), and 24 late coronary revascularizations (13%). The average annual rates were 5.4% for mortality, 2.2% for MI, 2.5% for late coronary revascularization, and 8.0% for combined events with an additional six coronary revascularizations performed within 60 days of AXT. By univariate analysis, patients who died were older but body mass index and blood pressure were similar and resting heart rate was lower in survivors vs. nonsurvivors. Major coronary risk factors, diabetes, coronary artery disease, or congestive heart failure were present in 18–82% of patients. However, clinical characteristics together did not attain statistical significance for the prediction of mortality (Table 1), MI (P > 0.05), or late coronary revascularization alone (P > 0.05) but did predict death and MI combined (Table 2). Age also was prognostic of mortality (Table 1) and death and MI combined (Table 2).

Exercise characteristics.

AXT MPI studies were performed to evaluate chest pain (61%), for preoperative risk stratification (23%), assessment of dyspnea (7%), functional capacity (3%), or coronary artery disease in patients with coronary risk factors (6%). Patients could not perform treadmill or leg cycle ergometer exercise because of orthopedic (lumbosacral spine, hip, knee, or foot) disorders (55%), severe claudication or foot ulcers (21%), spinal cord or lower extremity neurologic or myopathic conditions (13%), one or both lower extremity amputations (5%), and various other reasons (mainly morbid obesity and severe pulmonary disease) in the remaining 5%.

AXT capacity was predictive of survival by both univariate and multivariate analysis, whether evaluated as a continuous variable (Table 1) or stratified into equivalent-sized groups of high (≥3 METs; mean = 3.8 ± 0.6 METs) and low (<3 METs; mean = 2.3 ± 0.4 METs) AXT capacity (P < 0.05, HR 0.49, CI 0.13–0.84). The incidence of death and MI combined also was less in the group with higher METs (P < 0.05, HR 0.53, CI 0.21–0.85), but AXT capacity was not associated with MI or late coronary revascularization alone (P > 0.05). Similar results were obtained for AXT capacity unadjusted for weight (expressed as peak power output in kpm or in W). The peak work rate was 469 ± 174 kpm (77 ± 28 W) in survivors and 313 ± 143 kpm (51 ± 23 W) in nonsurvivors (P < 0.01). For survivors without MI, the peak work rate was 473 ± 171 kpm (77 ± 28 W) vs. 337 ± 162 kpm (55 ± 26 W) in those experiencing death or MI (P < 0.01).

Exercise hemodynamics.

By univariate analysis, peak heart rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressure were similar, but delta heart rate and PRPP were both lower in patients who died (Table 1) and delta heart rate was higher in patients with MI-free survival (Table 2). However, in the multivariate model, neither delta heart rate nor PRPP remained predictive of mortality alone or death and MI combined after inclusion of age, clinical variables, METs, and MPI data (Tables 1 and 2). None of these variable was associated with MI or late coronary revascularization alone (all P > 0.05).

Symptoms.

The endpoint of AXT was fatigue (79%), dyspnea (12%), anginal chest pain (3%), dysrhythmias (3%), and other reasons in the remaining 3%. None of these endpoints was predictive of clinical outcome, except for an association of fatigue with MI-free survival (P = 0.01, HR 0.51, CI 0.24–0.78).

Electrocardiogram.

A positive AXT ECG (14% of total tests) was predictive of MI (29% positive vs. 12% positive without subsequent MI; P < 0.05, HR 2.61, CI 2.13–3.10) and also prognostic of death and MI combined (Table 2) but not mortality (Table 1) or late coronary revascularization alone (P > 0.05).

MPI results.

A total of 106 (57%) AXT MPI evaluations were abnormal with perfusion defect characteristics shown in Tables 1 and 2. A positive AXT ECG was associated with both size and type of defect (P = 0.01 for size and P < 0.01 for reversible defects, Table 3). An abnormal MPI study was predictive of mortality (Table 1) and death and MI combined (Table 2) by both univariate and multivariate analysis, but did not predict MI or late coronary revascularization alone (both P > 0.05). By univariate analysis, large, small, and fixed perfusion defects also were associated with mortality and death and MI combined and moderate-sized defects closely approached statistical significance for prediction of mortality (Tables 1 and 2). The sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of a positive AXT ECG and an abnormal MPI study for prediction of mortality alone, MI alone and death and MI combined are shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Relationship between arm exercise ECG and MPI defect size and type

| Positive ECG (n = 26) |

Negative ECG (n = 160) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All sizes | Large = 12 (46%) | Moderate = 5 (19%) | Small = 5 (19%) | Normal = 4 (15%) | All sizes | Large = 37 (23%) | Moderate: = 20 (13%) | Small = 27 (17%) | Normal = 76 (48%) | |

| All types | ||||||||||

| Reversible | 7 (27%) | 2 | 2 | 3 | — | 16 (10%) | 4 | 2 | 10 | — |

| Mixed | 6 (23%) | 5 | 0 | 1 | — | 22 (14%) | 14 | 5 | 3 | — |

| Fixed | 9 (35%) | 5 | 3 | 1 | — | 46 (29%) | 19 | 13 | 14 | — |

Table 4.

Accuracy of arm exercise ECG and MPI in predicting outcome

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | ||||

| ECG | 17% | 87% | 35% | 73% |

| MPI | 77% | 51% | 38% | 85% |

| MI | ||||

| ECG | 29% | 88% | 23% | 91% |

| MPI | 62% | 44% | 12% | 90% |

| Death or MI | ||||

| ECG | 20% | 89% | 50% | 68% |

| MPI | 71% | 50% | 43% | 76% |

Kaplan-Meier survival curves and incremental prognostic value.

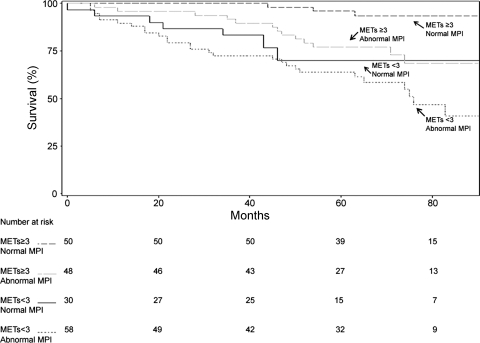

Kaplan-Meier survival and MI-free survival curves illustrating the effects of stratification of participants into four groups based on high or low AXT capacity and normal or abnormal MPI results are depicted in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. By this analysis, both low AXT capacity and abnormal MPI results were related to mortality and death and MI combined (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0002, respectively). Similarly, by global Wald-Chi squared analysis, AXT capacity and MPI findings contributed independent incremental value to age and clinical variables for prediction of survival (Fig. 3) and MI-free survival (Fig. 4). However, MPI results only approached statistical significance for adding incremental value in prognostication of death and MI combined after inclusion of ECG data in the model (Fig. 4). Delta heart rate and PRPP did not contribute additional incremental value to these variables (both P > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for arm exercise capacity and myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) results. METs, resting metabolic equivalents.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier myocardial infarction (MI)-free survival curve for arm exercise capacity and MPI results.

Fig. 3.

Incremental prognostic value for prediction of death.

Fig. 4.

Incremental prognostic value for prediction of death and MI combined.

DISCUSSION

Both Kaplan-Meier and global Wald-Chi squared analyses of our results indicate that AXT capacity provides equivalent incremental value to MPI data for prediction of long-term (>5 yr) all-cause mortality and MI-free survival, after adjustment for age and clinical variables in high-risk older patients unable to perform lower extremity exercise. To our knowledge, the present investigation is the first to assess the relative value of demographic, clinical, exercise, and MPI variables for prognostication of clinical outcome with AXT. Previous studies of treadmill or leg cycle ergometer exercise have revealed a highly significant relationship between exercise capacity and survival (5, 7, 11, 21, 23, 28). However, our results uniquely demonstrate the importance of AXT MPI evaluations for optimal prognostication of mortality, in contrast to pharmacological MPI studies, which do not provide information on functional capacity or hemodynamic, symptomatic, or ECG responses to the relevant physiological stress of exercise. The current data are also consistent with investigations reporting that treadmill or leg cycle ergometer exercise capacity and other exercise variables have equivalent or greater value than MPI results for prediction of all-cause or cardiac mortality (17, 20, 28).

Hachamovitch et al. (14) observed that severely abnormal MPI evaluations were predictive of cardiac death with both treadmill exercise and adenosine stress. However, patients with known coronary artery disease were found by Stein et al. (29) to have larger reversible perfusion defects and a higher incidence of transient ischemic dilatation and lung uptake, both markers of hemodynamically severe coronary disease, with AXT plus dipyridamole than with dipyridamole MPI thallium stress alone. Thus, in addition to providing valuable prognostic and clinical information such as exercise capacity, hemodynamic, symptomatic and ECG responses to the relevant physiological stress of exercise, AXT may elicit more severe MPI abnormalities and have greater sensitivity for detection of MPI markers of significant coronary disease than pharmacological stress.

The discrepant findings of previous treadmill or leg cycle ergometer scintigraphic studies, with respect to the incremental prognostic value of MPI data, could be related to disparate patient population characteristics or clinical endpoints. For example, Snader et al. (28) excluded patients with previous cardiac procedures or known disease, all participants in their study performed treadmill exercise, and exercise capacity was greater than in our patient population. In one investigation of Hachamovitch et al. (13), patients with previous MI or cardiac procedures also were excluded and cardiac death and MI, rather than all-cause mortality, were the clinical endpoints. Fagan et al. (9) and Chatziioannou et al. (8) included only patients who could complete at least stage 3 of the Bruce protocol and most clinical events in these two studies were hospitalizations or coronary revascularizations rather than death or MI. Our patient population was at considerably higher risk of adverse events than participants in all of these investigations, based on prevalence of known coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and coronary risk factors as well as inability to perform conventional (treadmill) exercise. This was substantiated by 5.4% and 8% average annual all-cause mortality and combined event rates, respectively, compared with ≤2% annual death or MI rates in the four preceding studies. Furthermore, there were no exclusion criteria in our investigation. Nevertheless, our conclusion that AXT MPI data are incrementally predictive of mortality is consistent with reports demonstrating the validity of stress MPI for prognostication of increased cardiac death or overall mortality rates in relatively high-risk populations of patients undergoing treadmill or leg cycle ergometer imaging evaluations (14, 24, 25, 31).

Numerous studies have shown that exercise MPI is more sensitive than the exercise ECG for detection of coronary artery disease (7, 8, 24). However, our data indicate that a positive AXT ECG is predictive of death and MI combined and MI alone, with no significant independent incremental prognostic value of MPI for the former endpoint. These findings may be explained by the fact that a positive AXT ECG was associated with a higher incidence of reversible defects and larger defect size than a negative AXT ECG, thus accounting for a significant portion of the predictive value of higher risk MPI variables. This interpretation is supported by the observation that MPI data were incrementally predictive of MI and death combined if the AXT ECG results were not entered into the model. Bourque et al. (6) reported a very low prevalence of significant ischemic MPI defects in patients with high exercise capacity and a negative treadmill ECG. Thus our AXT results are consistent with investigations indicating that the risk of future MI, cardiac death, all-cause mortality or important left ventricular ischemia is related to the severity of positive leg exercise ECG findings (6, 7, 18, 21). Our data also concur with results of other studies reporting a significant relationship between one or more of these adverse outcomes and stress MPI abnormalities (14, 20, 25, 31).

By univariate analysis, large, small, and fixed but not moderate-sized, reversible, or mixed perfusion defects were predictive of all-cause mortality and death and MI combined. The absence of specific prognostic value of reversible defects for these adverse outcomes may initially seem at variance with findings in some previous studies (25, 31). However, this apparent discrepancy is likely to be related to the relatively small size of our investigation as well as the fact that fixed and large perfusion defects were more numerous in our patient population than reversible, mixed, or moderate-sized defects, reflecting the high-risk characteristics of our participants. Even in the much larger studies of Hachamovitch et al. (14) and Vanzetto et al. (31), only severely abnormal MPI results, including both reversible and fixed perfusion defects, were consistently predictive of cardiac death and MI combined.

Our findings are applicable to a large and growing population of patients unable to perform leg exercise, which may exceed 20% and approach 40% of individuals referred for stress tests in many institutions (14). Nearly 25% of our AXT MPI studies were preoperative evaluations, most commonly for major vascular surgery or lower extremity orthopedic procedures. However, morbid obesity and diabetes are increasingly prevalent and AXT may be more suitable than treadmill or leg cycle ergometer exercise for individuals with body mass index greater than 35–40 kg/m2, significant leg claudication, or lower limb amputations. Spinal cord injuries and lower extremity amputations are particularly common in Gulf War veterans and other trauma victims, for whom AXT is often the only practical form of exercise stress or rehabilitation.

A limitation of our data is that it was acquired before defect severity, summed defect scores, or gated image processing were employed at our institution, facilitating long-term follow-up but providing less advanced imaging technology. However, semiquantitative visual and quantitative computer analyses of perfusion defects are reported to yield similar results (4) and may be more sensitive for evaluation of myocardial ischemia than data on left ventricular systolic function (32).

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that AXT and MPI results both add independent incremental and approximately equivalent predictive value to demographic and clinical variables for prognostication of all-cause mortality and death and MI combined in high-risk older patients unable to perform lower extremity exercise. The AXT ECG also was predictive of MI and death and MI combined. These results emphasize the importance of exercise variables, particularly AXT capacity, for optimal prognostication of hard endpoints of clinical outcome in patients historically referred for pharmacological imaging stress tests.

GRANTS

N. A. Ilias-Khan was supported by an American Medical Association Foundation Seed Grant Research Award for 2007 (Chicago, Il) and by a Washington University Mentors in Medicine research award for 2007 (St. Louis, MO). H. Xian was supported by NIH grants RO1 DA-020810, RO1 AG-022381-03, and RO1 AG-022982-01 (Washington DC). C. Inman and W. H. Martin were supported by a Merit Review Grant from the Dept. of Veterans Affairs (Washington DC).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present addresses: A. K. Chan, Div. of Cardiology, Univ. of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT; N. A. Ilias-Khan, Sacred Heart Medical Center, River Bend, OR; C. Inman, Program in Physical Therapy, Washington Univ. School of Medicine.

Melanie Bowman, an exercise physiologist at the STL VAMC, provided invaluable assistance with scheduling, data collection, and equipment management. In addition, the contributions of undergraduates and medical students of Washington University and Washington University School of Medicine, respectively, who assisted with collection and archiving of data, are recognized.

The authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

REFERENCES

- 1. Astrand PO, Rodahl K. Textbook of Work Physiology (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, 1986, chapt. 8, p. 365 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Astrand PO, Saltin B. Maximal oxygen uptake and heart rate in various types of muscular activity. J Appl Physiol 16: 977–981, 1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balady GJ, Weiner DA, Rothendler JA, Ryan TJ. (with the technical assistance of Mangene C, LaGambina J, McCarthy C.). Arm exercise-thallium imaging testing for the detection of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 9: 84–88, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berman DS, Kang X, Van Train KF, Lewin HC, Cohen I, Areeda J, Friedman JD, Germano G, Shaw LJ, Hachamovitch R. Comparative value of automatic quantitative analysis vs. semi-quantitative visual analysis of exercise myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 32: 1987–1995, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blair SN, Kohl HW, 3rd, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Clark DG, Cooper KH, Gibbons LW. Physical fitness and all-cause mortality: a prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA 262: 2395–2401, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bourque JM, Holland BH, Watson DD, Beller GA. Achieving an exercise workload ≥10 metabolic equivalents predicts a very low risk of inducible ischemia. Does myocardial perfusion imaging have a role? J Am Coll Cardiol 54: 538–545, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chaitman BR. Exercise stress testing. In: Braunwald's Heart Disease. A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine (7th ed.), edited by Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Braunwald E. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005, vol. 1, chapt. 10, p. 153–185 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chatziioannou SN, Moore WH, Ford PV, Fisher RE, Vei-Vei L, Alfaro-Franco C, Dhekne RD. Prognostic value of myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with high exercise tolerance. Circulation 99: 867–872, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fagan LF, Shaw L, Kong BA, Caralis DG, Wiens RD, Chaitman BR. Prognostic value of exercise thallium scintigraphy in patients with good exercise tolerance and a normal or abnormal exercise electrocardiogram and suspected or confirmed coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 69: 607–611, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fisher SG, Weber L, Goldberg J, Davis F. Mortality ascertainment in the veteran population: alternatives to the National Death Index. Am J Epidemiol 141: 242–250, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT, Chaitman BR, Fletcher GF, Froelicher VF, Mark DM, McCallister BD, Mooss AN, O'Reilly MG, Winter WL., Jr ACC/AHA 2002 guidelines for exercise testing. A report of the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines). J Am Coll Cardiol 40: 1531–1540, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grover-McKay M, Milne N, Atwood JE, Lyons KP. Comparison of thallium-201 single-photon computed tomographic scintigraphy with intravenous dipyridamole and arm exercise. Am Heart J 127: 1516–1520, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico JA, Friedman J, Diamond GA. Exercise myocardial perfusion SPECT in patients without known coronary artery disease. Circulation 93: 905–914, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Shaw LJ, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico JA, Friedman J, Diamond GA. Incremental prognostic value of myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography for the prediction of cardiac death. Circulation 97: 535–543, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ilias NA, Xian H, Inman C, Martin WH., 3rd Arm exercise testing predicts clinical outcome. Am Heart J 157: 69–76, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Keyser RE, Andres EF, Wojta DM, Gullett SL. Variations in cardiovascular response accompanying differences in arm-cranking rate. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 69: 941–945, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lauer MS, Francis GS, Okin PM, Pashkow FJ, Snader CE, Marwick TH. Impaired chronotropic response to exercise stress testing as a predictor of mortality. JAMA 281: 524–529, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laukkkanen JA, Kurl S, Lakka TA, Tuomainen TP, Rauramaa R, Salonen R, Eranen J, Salonen JT. Exercise-induced silent myocardial ischemia and coronary morbidity and mortality in middle-aged men. J Am Coll Cardiol 38: 72–79, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leeper NJ, Dewey FE, Ashley EA, Sandri M, Tan SY, Hadley D, Myers J, Froelicher V. Prognostic value of heart rate increase at onset of exercise testing. Circulation 115: 468–474, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marie PY, Danchin N, Durand JF, Feldman L, Grentzinger A, Olivier P, Karcher G, Julliere Y, Virion JM, Beurrier D, Cherrier F, Bertrand A. Long-term prediction of major ischemic events by exercise thallium-201 single-photon emission computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 26: 879–886, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mark DB, Shaw L, Harrell FE, Jr, Hlatky MA, Lee KL, Bengtson JR, McCants CB, Califf RM, Pryor DB. Prognostic value of a treadmill exercise score in outpatients with suspected coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 325: 849–853, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martin WH, 3rd, Berman WI, Buckey JC, Snell PG, Blomqvist CG. Effects of active muscle mass size on cardiopulmonary responses to exercise in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 14: 683–694, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, Do D, Partington S, Atwood JE. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med 346: 793–801, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parisi AF, Hartigan PM, Folland ED. for the ACME Investigators Evaluation of exercise thallium scintigraphy versus exercise electrocardiography in predicting survival outcomes and morbid cardiac events in patients with single- and double-vessel disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 30: 1256–1263, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pollack SG, Abbott RD, Boucher CA, Beller GA, Kaul S. Independent and incremental prognostic value of tests performed in hierarchical order to evaluate patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Circulation 85: 237–248, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. SAS SAS System for Windows. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schwartz JF. Clinical decision making in cardiology. Braunwald's Heart Disease. A Textbook of Medicine (7th ed), edited by Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Braundwald E. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, vol. 1, chapt. 3, p. 29–30 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Snader CE, Marwick TH, Pashkow FJ, Harvey SA, Thomas JD, Lauer MS. Importance of estimated functional capacity as a predictor of all-cause mortality among patients referred for exercise thallium single-photon emission computed tomography: report of 3400 patients from a single center. J Am Coll Cardiol 30: 641–648, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stein L, Burt R, Oppenheim B, Schauwecker D, Fineberg N. Symptom-limited arm exercise increases detection of ischemia during dipyridamole tomographic thallium stress testing in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 75: 568–572, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stratmann HG, Williams GA, Wittry MD, Chaitman BR, Miller DD. Exercise technetium 99-m sestamibi tomography for cardiac risk stratification of patients with stable chest pain. Circulation 89: 615–622, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vanzetto G, Ormezzano O, Fagret D, Comet M, Denis B, Machecourt J. Long-term additive prognostic value of thallium-201 myocardial perfusion imaging over clinical and exercise stress test in low to intermediate risk patients. Circulation 100: 1521–1527, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Udelson JE, Dilsizian V, Bonow RO. Nuclear cardiology. Braunwald's Heart Disease. A Textbook of Medicine (7th ed), edited by Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Braundwald E. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, vol. 1, chapt. 13, p. 303–315 [Google Scholar]