SUMMARY

Galline Ex-FABP was identified as another candidate antibacterial, catecholate siderophore binding lipocalin (siderocalin) based on structural parallels with the family archetype, mammalian Siderocalin. Binding assays show that Ex-FABP retains iron in a siderophore-dependent manner in both hypertrophic and dedifferentiated chondrocytes, where Ex-FABP expression is induced after treatment with proinflammatory agents, and specifically binds ferric complexes of enterobactin, parabactin, bacillibactin and, unexpectedly, monoglucosylated enterobactin, which does not bind to Siderocalin. Growth arrest assays functionally confirm the bacteriostatic effect of Ex-FABP in vitro under iron-limiting conditions. The 1.8Å crystal structure of Ex-FABP explains the expanded specificity, but also surprisingly reveals an extended, multi-chambered cavity extending through the protein and encompassing two separate ligand specificities, one for bacterial siderophores (as in Siderocalin) at one end and one specifically binding co-purified lysophosphatidic acid, a potent cell signaling molecule, at the other end, suggesting Ex-FABP employs dual functionalities to explain its diverse endogenous activities.

INTRODUCTION

Galline Extracellular Fatty Acid Binding Protein (Ex-FABP) is expressed in serum, egg whites and granulocytes; Ex-FABP mRNA is further found in several tissues including skin, brain, heart and kidney (Dozin et al., 1992; Gentili et al., 2005; Guerin-Dubiard et al., 2006). Ex-FABP is also secreted in large amounts from hypertrophic chondrocytes and isolated myoblasts during muscle fiber differentiation (Cancedda et al., 1990; Dozin et al., 1992; Gentili et al., 2005; Manduca et al., 1989). In adult chickens, Ex-FABP is expressed in response to inflammation and tissue degeneration, such as osteoarthritis and tibial dyschondroplasia (Cermelli et al., 2000). Ex-FABP has previously been shown to: (1) affect cartilage and muscle cell differentiation, heart development and embryonic survival; and (2) selectively bind fatty acids like oleic, linoleic and arachidonic acid (Cancedda et al., 1996; Di Marco et al., 2003; Gentili et al., 2005). However, the exact molecular mechanisms by which Ex-FABP exerts these incongruent activities has not been determined, nor is it understood how binding simple fatty acids would affect these processes.

Ex-FABP belongs to the lipocalin family of proteins, many of which bind fatty acids specifically or nonspecifically, but also disparate ligands ranging from small molecules to proteins (Åkerstrom et al., 2000; Clifton et al., 2009). Despite the confusing nomenclature, Ex-FABP is a lipocalin (Ganfornina et al., 2000) and not a member of the fatty acid-binding protein family, proteins that coordinate lipid responses in cells (Zimmerman and Veerkamp, 2002). In spite of limited sequence conservation, lipocalins share a conserved core fold consisting of an eight-stranded antiparallel β-barrel flanked by single α and 310helices; the ligand binding site, or calyx, usually comprising a deep, narrow cavity, is located along the hub of the β-barrel (Flower, 1994). Structural parallels between Ex-FABP and Siderocalin (Scn; also Lipocalin 2 (Lcn2), Neutrophil Gelatinase Associated Lipocalin (NGAL), 24p3) (Holmes et al., 2005), based on the initial NMR structure of the closely related quail protein Q83 (88% identical to Ex-FABP) (Hartl et al., 2003), suggested that Ex-FABP was another ‘siderocalin’: lipocalins with antimicrobial iron-sequestering and endogenous iron transport activities (Clifton et al., 2009). Siderocalins interfere with microbial iron acquisition by binding bacterial siderophores: small molecule, ferric-specific iron chelators. Scn, the family archetype, is a potent component of innate immunity, providing significant protection from infections. Scn binds a variety of ferric siderophores, including enterobactin (FeEnt), bacillibactin (BB), carboxymycobactins (CMB) and other phenolate siderophores with high affinity using three positively-charged calyx residues as key recognition elements also seen in Ex-FABP; a subsequent NMR analysis confirmed that cotarnine Q83 binds FeEnt, but did not fully reveal the details of Ent recognition (Coudevylle et al., 2010). Beyond its antibacterial properties, Scn has also been shown to have pleiotropic effects on cellular differentiation, apoptosis and tumorigenesis presumably through Scn-mediated, endogenous iron transport (Clifton et al., 2009). Scn also binds weakly to fatty acids because such moieties constitute CMB substructures (Goetz et al., 2000; Holmes et al., 2005).

Evidence supporting the hypothetical identification of Ex-FABP as another siderocalin includes its localization in egg whites coincident with other antibacterial and nutrient sequestration proteins (such as avidin and ovotransferrin) and a spectrum of endogenous cellular effects similar to Scn. Confirming this hypothesis, we show here that Ex-FABP: (1) binds iron in a siderophore-dependent manner in cultures of chicken chondrocytes; (2) specifically and tightly binds a range of catecholate siderophores; (3) inhibits the growth of E. coli and B. subtilis in culture; and (4) specifically binds FeEnt hydrolysis products in the co-crystal structure. However, the crystal structure of Ex-FABP unexpectedly revealed that the calyx is considerably enlarged and extends through the entire protein, encompassing multiple potential ligand binding sites, with the siderophore binding site occupying one end only. The other end of the calyx forms a large chamber that specifically retains particular isoforms of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), a potent eukaryotic signaling molecule (Aoki et al., 2008; Noguchi et al., 2009), during purification from bacteria. This result suggests that, while the antibacterial and endogenous cellular effects of Scn are proposed to be linked to siderophore-mediated iron transport, the antibacterial and endogenous cellular effects of Ex-FABP may be related to the binding of distinct ligands. Comparisons of a subsequent NMR structure of LPA-free Q83 (Coudevylle et al., 2010) and the Ex-FABP:LPA complex crystal structure showed dramatic, global conformational changes apparently induced by LPA binding, showing that avian siderocalins can also act as LPA sensors.

RESULTS

Endogenously expressed Ex-FABP binds iron in cell cultures

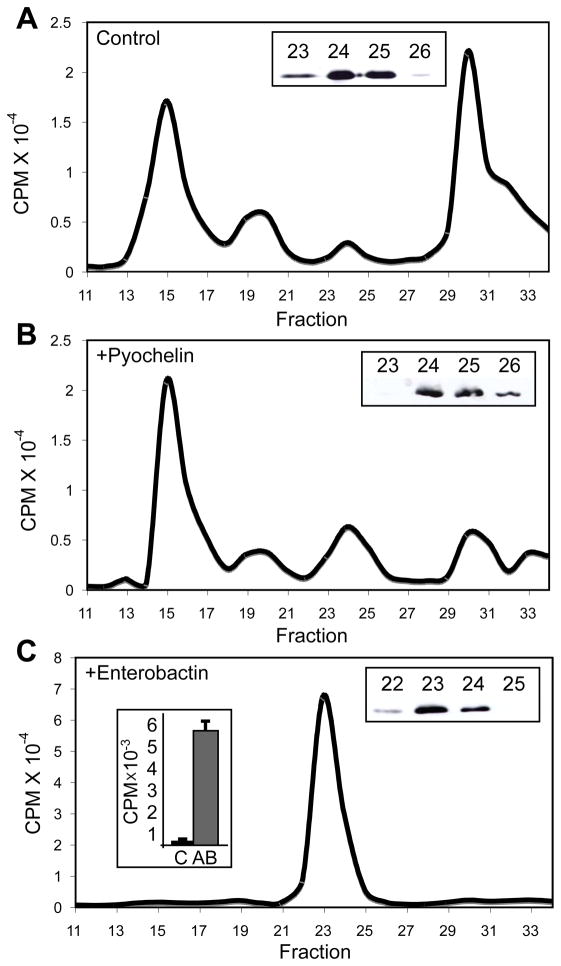

Cultured chondrocytes were supplemented with 55FeCl3 in the presence or absence of an added siderophore (Ent or pyochelin) and the resulting culture supernatants were then fractionated by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) (Figure 1). In Figure 1, dedifferentiated cells that express Ex-FABP upon LPS treatment, little iron co-eluted with Ex-FABP in the absence of siderophores. In the presence of added Ent, the bulk of the iron present in culture co-eluted with Ex-FABP; in the presence of pyochelin, only a portion of the iron present in the medium co-eluted with Ex-FABP. Iron binding was further confirmed by immunoprecipitation of Ex-FABP/ferric siderophore complexes with anti-Ex-FABP antibodies. Iron binding by Ex-FABP from hypertrophic chondrocytes was not detected in the absence of added siderophore, while in the presence of siderophore iron was clearly bound (Figure S1). These results are consistent with the identification of Ex-FABP as a siderocalin, showing that the protein does not bind iron directly, but requires the presence of a mediating siderophore, with Ent supporting tighter binding than pyochelin.

Figure 1. Secreted Ex-FABP retains ferric Pyochelin and FeEnt in cultures of dedifferentiated chondrocytes.

SEC analyses of culture supernatants from dedifferentiated chondrocytes, stimulated with endotoxin to induce the expression of Ex-FABP, demonstrated that added 55FeCl3 did not co-elute with Ex-FABP in (A) the absence of added siderophores, but did co-elute with Ex-FABP in the presence of added, iron-free (B) Pyochelin or (C) Ent. Insets (A, B, C; right side) show Western blot analyses with Ex-FABP polyclonal antiserum identifying Ex-FABP containing fractions and (C; left side) immunoprecipitation of 55FeCl3 by Ex-FABP specific IgG on Ex-FABP containing fractions in the presence of added Ent (C: rabbit IgG control; AB: with Ex-FABP rabbit IgG). See also Figures S1, S2 and S3.

Recombinant Ex-FABP co-purifies with catecholate ferric siderophores

As with Scn (Goetz et al., 2002), some preparations of Ex-FABP recombinantly expressed in E. coli co-purified with a dark red chromophore, spectroscopically indistinguishable from FeEnt, which could not be removed without denaturing the protein. In order to isolate ligand-free Ex-FABP for binding and structural studies, the Ent synthesis pathway in E. coli was disrupted by engineering a BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL entB− strain; entB controls the conversion of isochorismate to 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,3-DHBA), an early obligate step in Ent biosynthesis (Nahlik et al., 1987). The entB− strain grew more slowly than the parent strain and required the addition of supplemental iron, but protein purified from this strain was free of co-purifying chromophores (data not shown). When Ex-FABP was expressed cytoplasmically in E. coli, the purified protein displayed a mixture of reduced and oxidized forms (Ex-FABP is predicted to contain a single intrachain disulfide bond conserved in most lipocalins; Figure S2). The reduced form of the protein readily reacted with maleimide conjugated biotinylation reagents, which facilitated its removal, enabling purification (Figure S3). As an alternative, the protein was expressed periplasmically in E. coli by replacing the initiator methionine residue (which had replaced the native leader peptide for cytoplasmically-targeted expression) with the pelB signal sequence. This approach yielded homogenous, monodisperse, fully-oxidized Ex-FABP more readily than maleimide purification, which was also free of co-purifying chromophores (Figure S3).

Ex-FABP binds a range of bacterial ferric siderophores

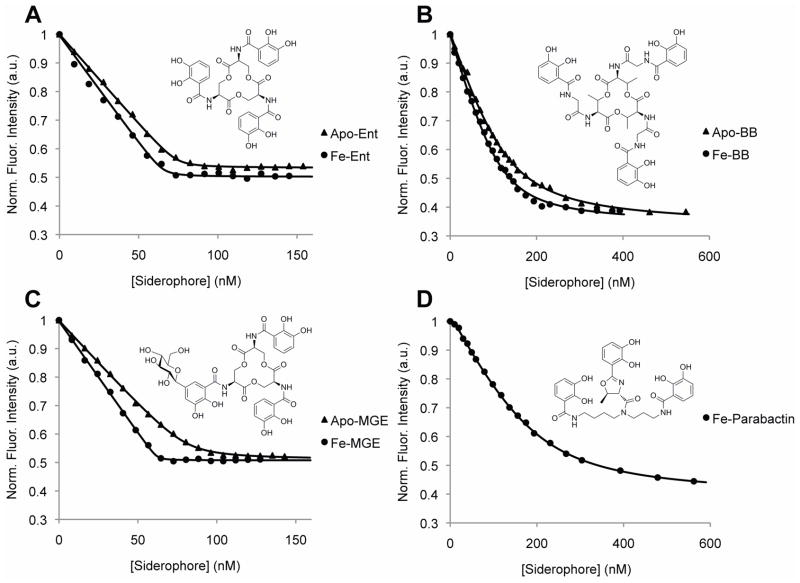

Qualitative binding assays were used to broadly define Ex-FABP’s specificity for different siderophores. Following extensive washing, UV-VIS spectroscopy showed clear retention of FeEnt, like Scn, but not FeCMB, unlike Scn (Figure S4). P. aeruginosa, which commonly infects fertile eggs and chicks leading to significant mortality (Barnes, 1991), produces pyochelin and pyoverdin, siderophores quite chemically distinct from Ent. Surprisingly, Ex-FABP also retained both of these siderophores as ferric complexes in qualitative binding assays, both of which fail to bind measurably to Scn (Holmes et al., 2005). Since qualitative filter retention assays may show retention of weakly-binding ligands if dissociation rates are slow enough to kinetically trap the ligand, fluorescence spectroscopy was then used to directly measure affinities between Ex-FABP and various ferric siderophores (Figure 2 and Table 1). Similar to Scn, Ex-FABP binds apo and ferric complexes of catecholate-type siderophores, such as Ent, parabactin (PaB) and BB, with nanomolar to tens-of-nanomolar equilibrium dissociation constants (KD). Also like Scn, Ex-FABP does not show measurable fluorescence quenching (FQ) with modified catecholate siderophores, like ferric diglucosylated Ent (FeDGE) or ferric petrobactin, or hydroxamate-, citrate- or mixed-type siderophores, like ferric desferrioxamine (DFO) or ferric rhizoferrin. Unexpectedly, Ex-FABP bound ferric monoglucosylated Ent (FeMGE) with a nanomolar KD, where this siderophore is strictly precluded from binding to Scn by extensive steric clashes in the calyx (Fischbach et al., 2006a; Fischbach et al., 2006b). Significant FQ was not observed when Ex-FABP was mixed with either ferric pyochelin or pyoverdine, suggesting that these interactions are characterized by dissociation constants weaker than 0.6 μM (the estimated detection ceiling of this technique) or that binding of these ferric siderophores does not quench intrinsic fluorescence.

Figure 2. Ex-FABP tightly binds apo and ferric catecholate siderophores.

Inherent fluorescence was strongly quenched by adding (A) apo-Ent or FeEnt, (B) apo-BB or FeBB, (C) apo-MGE or FeMGE and (D) FePaB to Ex-FABP; derived KD values are listed in Table 1. Point-by-point averages of three independent titrations for each compound are shown with calculated DYNAFIT (Kuzmic, 1996) nonlinear regression fits, used to estimate dissociation constants, superimposed. See also Figure S4.

Table 1.

Apo and Ferric Siderophore Binding Affinities

| Siderophore | KD (nM)† | Siderophore type | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| apo(Ent) | 0.5 ± 0.15 | catechol |

Escherichia coli Salmonella enterica |

| [FeIII(Ent)]3− | 0.22 ± 0.06 | catechol |

Escherichia coli Salmonella enterica |

| [FeIII(PaB)]2− | 42 ± 8 | catechol/HPO |

Paracoccus denitrificans |

| apo(BB) | 30 ± 2 | catechol | Bacillus sp. |

| [FeIII(BB)]3− | 14 ± 2.0 | catechol | Bacillus sp. |

| apo(MGE) | 1.1 ± 0.15 | catechol derivative | Salmonella enterica |

| [FeIII(MGE)]3− | 0.07 ± 0.02 | catechol derivative | Salmonella enterica |

| [FeIII(DGE)]3− | >600 | catechol derivative | Salmonella enterica |

| [FeIII(Pyochelin)2]1− | >600 | HPT |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| [FeIII(Pyoverdine)]1− | >600 | catechol derivative |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| [FeIII(Rhizoferrin)] | >600 | citrate | fungal |

| [FeIII(DesferrioxamineB)] | >600 | hydroxamate | Streptomyces pilosus |

| [FeIII2(Alcaligin)3] | >600 | hydroxamate | Bordetella pertussis |

| [FeIII(Petrobactin)]2− | >600 | citrate/catechol |

Bacillus anthracis Bacillus cereus |

| [FeIII(Aerobactin)] | >600 | citrate/hydroxamate | Escherichia coli |

| [FeIII(ExochelinMS)] | >600 | hydroxamate |

Mycobacteria smegmatis |

| [FeIII(Coprogen)] | >600 | hydroxamate | Neurospora crassa |

The detection threshold for this assay corresponds to a KD ≤ 600 nM

Ex-FABP inhibits bacterial growth

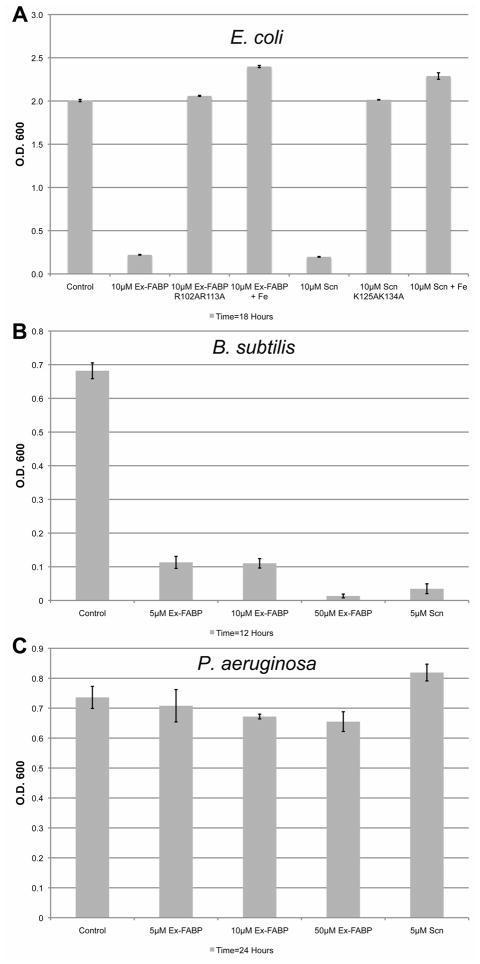

The antibacterial properties of Ex-FABP were directly tested in vitro to determine whether siderophore binding was tight enough to effectively sequester iron. Ex-FABP inhibited the growth of E. coli and B. subtilis (Figure 3A and 3B) with an effect comparable to that described for Scn (Goetz et al., 2002), consistent with the high affinity of Ex-FABP for siderophores from these bacteria, but did not arrest the growth of P. aeruginosa (Figure 3C), consistent with the apparently weak affinity of Ex-FABP for pseudomonad siderophores. A K125A/K134A Scn mutant, which ablates siderophore binding, also ablates in vitro bacteriostatic activity, consistent with the determination that bacteriostatic activity is mediated by sequestering iron as ferric siderophore complexes. The structurally analogous mutant of Ex-FABP, R101A/R112A, also ablates in vitro bacteriostatic activity, suggesting an analogous activity. Rescue of bacterial growth was also observed by the addition of stoichiometric amounts of iron, demonstrating that the bacteriostatic activity was exerted solely through iron sequestration.

Figure 3. Ex-FABP and Scn are bacteriostatic for E. coli and B. subtilis.

The bacteriostatic effect of Ex-FABP, Scn and ligand-binding mutants of Ex-FABP or Scn on the (A) BL21(DE3)-RIL E. coli strain, cultured in M9 minimal media, was determined by measuring culture densities after 18 hours. Growth was rescued by supplementing the cultures with stoichiometric amounts of FeCl3. Ex-FABP and Scn inhibit growth of (B) B. subtilis but do not effect the growth of (C) P. aeruginosa under iron-limited conditions.

The Ex-FABP crystal structure details siderophore recognition

Initial attempts to reproducibly grow diffraction-quality crystals failed despite extensive screening, multiple expression constructs, elimination of co-purifying siderophores, resolution of disulfide heterogeneity and in situ proteolysis (Dong et al., 2007). Successful crystallization was finally achieved when charged surface residues were replaced with alanines in order to promote the formation of crystal contacts (Derewenda, 2004; Derewenda and Vekilov, 2006) using a ‘best-guess’ strategy, with an R26A/E149A/E150A triple mutant reproducibly yielding well-ordered FeEnt complex crystals (dmin = 1.8Å; Table 2). Initial phase information was determined by molecular replacement.

Table 2.

Crystallographic Statistics

| Data collection | |

|---|---|

| Space group | P212121 |

| Lattice constants (Å) | a = 37.95 b= 68.89 c = 117.40 |

| Resolution (Å) | 44.68–1.8 (1.86–1.80) |

| Unique reflections | 27696 |

| Average redundancy | 4.87 (4.86) |

| Completeness (%) | 94.2 (94.4) |

| Rmerge (%) | 5.8 (37.5) |

| I/σ(I) | 11.0 (3.3) |

| Refinement statistics | |

|---|---|

| Rwork (%) | 20.2 |

| Rfree (%) | 23.3 |

| Number of atoms | |

| Protein | 2313 |

| LPA | 32 |

| FeDHBA | 12 |

| Water | 134 |

| R.M.S deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0136 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.4483 |

| Ramachandran | |

| Favored (%) | 93.0 |

| Allowed (%) | 7.0 |

| Generously allowed (%) | 0.0 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.0 |

The fold of Ex-FABP is typical of the lipocalin family, but with an extra non-canonical α-helix (residues 22–30; packing against the upper rim of the calyx) and short helical element (residues 139–141). The two molecules in the asymmetric unit (AU) are virtually identical (all-atom RMSD of 1.13Å) with the exception of residues 68 through 72, which cannot be modeled in molecule A but which form a turn in molecule B (Figure 4A). The structures of Ex-FABP and its homolog Q83 are significantly different despite sharing 88% sequence identity (backbone RMSD of 2.40Å). Most notable is the overall appearance of the backside (face opposite the canonical calyx opening) of the molecules; Q83 presents a much craggier surface where Ex-FABP presents a smoother, more closely packed or ‘clenched’ surface. This difference is the combined result of restructuring the N-terminal peptide from an extended structure, with a two-turn α-helix pointing distally into solvent in Q83, to a position more closely wrapped around the backside of the protein in Ex-FABP, along with small inwards movements of two neighboring loops (residues 40 to 45 and 89 to 94) in Ex-FABP (Figure 4B). These movements do not appear to be affected by crystal contacts, as both molecules in the Ex-FABP AU have superimposable structures; the loops involved are comparably well defined in the crystal (Ex-FABP) and NMR (Q83) structures. The loop sequences are highly conserved between Q83 and Ex-FABP and are, therefore, not affected by local sequence differences. The movement of the 89–94 loop has the additional consequence of ratcheting the position of the side-chain of Y94 (Ex-FABP)/Y95 (Q83) from packing against the loop (in Ex-FABP) to pushing against the long canonical α-helix (in Q83), which moves outward from the barrel by 1.5 to 2.0Å along the length of the helix in Q83.

Figure 4. Structure of Ex-FABP in complex with FeEnt.

(A) Cartoon ribbon representations of the structures of molecule A and molecule B in the AU, colored by secondary structure, are shown. The N- and C-termini of both molecules of Ex-FABP in the AU are indicated. (B) Backbone representations of the structures of the two Ex-FABP molecules in the AU (with carbons colored dark blue) are superimposed on similar representations (with carbons colored gray) of the sheaf of NMR solutions representing the structure of Q83 (Coudevylle et al., 2010). The side-chains of key LPA interacting residues are shown in licorice stick representations, with oxygens colored red. (C) Molecular surface representation of the Ex-FABP crystal structure is shown, colored by electrostatic potential, with the single, well-defined FeDHBA moiety and associated iron atom rendered in licorice stick representation, colored by atom type. Individual catechol binding pockets in the Ex-FABP calyx are indicated with arrows, numbered as in the Scn structure (Goetz et al., 2002). (D) A difference Fourier synthesis (with 3Fobs-2Fcalc coefficients), calculated with refine-omit phases and contoured at 1.5σ around the bound FeEnt breakdown products, is shown in a stereo-pair representation superimposed on an intact FeEnt molecule (carbons colored yellow) and the single, well-ordered DHBA moiety (carbons colored blue) in the calyx of molecule B.

Unlike most lipocalins, but a hallmark of the siderocalins, the calyx has a net overall positive charge due to the presence of three basic residues (K82, R101 and R112) corresponding to the three residues (R81, K125 and K134) key to siderophore binding in Scn. The calyx is highly sculpted with three lobes (designated pockets 1, 2 and 3, as in Scn), each of which is structured to accommodate a 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,3-DHBA) group. While there is difference electron density in the calyx of molecule B corresponding to a partially-intact FeEnt ligand at generous contouring levels (≤0.8 σ), only a single 2,3-DHBA moiety could be confidently modeled at conservative contouring levels (1.0 σ; Figure 4C). This is consistent with previous Scn:ferric siderophore complex structures, where a combination of positional freedom within the calyx and ligand hydrolysis contributes to ligand disorder; FeEnt-related siderophore ligands are often poorly defined in many wild-type Scn complex structures, even with hydrolysis resistant analogs (Goetz et al., 2002; Holmes et al., 2005).

Intact FeEnt was modeled into the complex structure with Ex-FABP based on the well-defined position of the single ferric 2,3-DHBA group, weaker electron density features corresponding to remainder of the intact siderophore, steric constraints imposed by the Ex-FABP calyx and Scn:siderophore complex structures (Figure 4D). Scn binds FeEnt and related siderophores by intercalating the side chains of three basic residues (R81, K125 and K134) between the catechol groups, with K125 and K134 playing a key role defining the pocket central to determining Scn’s broad siderophore specificity (Figure 5A). In the Ex-FABP structure, R101 and R112 provide significant electrostatic contributions with R112 reaching over to also contact the catechol in pocket 1 (Figures 5B and 5C). The side-chain of K82 in Ex-FABP contributes hydrogen bonds to the 3-OH of the catechol groups in pockets 1 and 3 and is within van der Waals contact distance to the iron atom, analogous to the ligand contacts provided by the side-chain of Y106 in Scn.

Figure 5. Binding of FeENT and FeMGE in the Ex-FABP binding site.

Arrangements between FeEnt and the side-chains of key positively-charged calyx residues are shown for (A) Scn (Goetz et al., 2002) with the side chains of residues Y106, K125 and K134 highlighted (carbons colored light grey), (B) Ex-FABP with the side-chains of residues K82, R101 and R112 highlighted (carbons colored dark grey) and (C) Q83 (Coudevylle et al., 2010) with the side-chains of residues K83, R102 and R113 highlighted (carbons colored light grey). In (A), (B) and (C) calyx pocket 1 is positioned at the back of the figure. The modeled complex of Ex-FABP and FeMGE is shown as (D) a close up view of the calyx (colored by electrostatic potential) and modeled FeMGE ligand shown in a licorice stick representation, colored by atom type and (E) and overall view of the molecular surface of Ex-FABP (colored by electrostatic potential) with the modeled FeMGE ligand shown in a CPK representation (colored by atom type). Note that in (D), one can see straight through the protein through the LPA channel through the opening into the bottom of the siderophore binding site (arrow).

Modeling MGE into the Ex-FABP structure by adding a glucose moiety to the FeEnt ligand in the complex structure revealed that Ex-FABP is readily able to accommodate the single glucose adduct in a extended pocket 3 (Figure 5D and E), confirming the FQ binding results. In Scn, pocket 3 is walled off by the side-chains of Y100 and R81, the latter side-chain observed in different rotamers (along with its neighbor, W79), accommodating different ligands in different complex structures. In Ex-FABP, the structural equivalent of R81 is T63 and the Scn loop containing Y100 (residue 94 to 104) is replaced with a much shorter loop in Ex-FABP (residues 77 to 80), both substitutions combining to extend pocket 3 in Ex-FABP relative to Scn.

The extended Ex-FABP calyx encompasses multiple ligand binding sites

An unusual feature of the Ex-FABP structure not seen in any other lipocalin, except in the updated NMR structure of the Ex-FABP ortholog Q83 (Coudevylle et al., 2010), is the extension of the calyx through the entire molecule, defining a roughly hourglass-shaped volume (Figure 6). The closest structural parallel is perhaps the tick histamine-binding lipocalin, which incorporates dual ligand binding pockets, each binding a single histamine, encompassing relatively small, separate volumes totally enclosed within the surface of the protein (Paesen et al., 1999). In Ex-FABP, however, the two well-defined cavities open into solvent at opposite ends of the protein, interconnected through a narrow constriction defined by the side-chains of residues I14, Y50, K82, R112 and Y114. The upper cavity comprises the siderophore-binding site while the second is primarily hydrophobic in character (lined by the side-chains of residues V8, L46, V48, F65, Y75, V84, V86, I97 and A99). In Scn and many lipocalins, a stretch of N-terminal residues (in Scn, the first 25) wraps around the bottom and up the side of the protein, capping any opening into the calyx from the backside. In Ex-FABP, the N-terminal sequence is much shorter than in Scn and does not pack against the body of the protein, contributing to the backside opening into the calyx, with the five (TVPDR; molecule A) or three (TVP; molecule B) most N-terminal residues in the expression construct also disordered in the structure.

Figure 6. Structure of Ex-FABP in complex with LPA.

(A) A stereo representation of a difference Fourier synthesis (with 3Fobs-2Fcalc coefficients), calculated with refine-omit phases and contoured at 1.5σ, around the modeled co-purifying LPA ligand and the side-chains of residues K82, R112 and Y114, is shown superimposed on a cartoon ribbon representation of the structure of Ex-FABP. (B) The side-chains of residues making specific hydrogen bonds to the phosphate moiety of LPA are shown in licorice stick representation, colored by atom type (carbons in molecule A: blue; carbons in molecule B: yellow). (C) A section of a molecular surface representation of the structure of molecule B in the AU of the Ex-FABP crystal structure, colored by electrostatic potential, is shown with LPA and modeled FeEnt bound; volumes were calculated with CASTp (Dundas et al., 2006). See also Figure S5 and Movie S1.

In both molecules in the AU, there was a large, well-defined feature in difference Fourier syntheses, not accounted for by protein or siderophore, filling the constriction and the second cavity that likely represented a tightly-bound, co-purified ligand (Figure 6A). Washing with high-phosphate and low pH citrate buffers failed to release this ligand as shown by the retention of this feature in subsequent difference Fourier syntheses, showing tight binding. These electron density features were best modeled as molecules of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), acylated on the 3-hydroxyl, with acyl tails that could confidently be modeled out to lengths of four methylene groups; these acyl tails clearly adopted different conformations in the two molecules in the AU (Figure 6B and 6C). Steric constraints likely preclude binding of LPA isoforms acylated on the 2-hydroxyl. The phosphate head group, the most well defined feature in Fourier syntheses, was bound in the constriction between cavities by the side-chains of Y50, K82, R112 and Y114 (Figure 6B). Extractions of purified, recombinant protein were transesterified and analyzed by GC/MS, showing the presence of ligands with C16:0 and C18:0 alkyl chain substituents, consistent with our identification of the co-purified ligand as LPA (Figure S5). Binding of LPA also explains the closure of the backside loops of Ex-FABP relative to Q83: the distal methylene groups of the LPA fatty acid moiety make direct contacts with side-chains from residues in each of the three loops that move inwards in Ex-FABP, effecting the conformational change. These residues include V8, F40 and Y91, which move by approximately 6, 8 or 6Å, respectively, in response to the presence of LPA, providing a ligand-sensitive trigger affecting the global structure of avian siderocalins. The NMR analysis of Q83 used protein that had been denatured and refolded in vitro specifically to remove co-purifying ligands, focusing on siderophores, insuring that the Q83 structure represents an ‘empty’ avian siderocalin structure (Coudevylle et al., 2010). A comparable approach failed with Ex-FABP (data not shown), necessitating our alternate approaches outlined above to remove siderophores with the unforeseen advantage of retaining co-purifying LPA. An alternative approach, disrupting the LPA binding site by introducing a V48E mutation predicted to ablate LPA binding by blocking the phosphate binding site, unfortunately also disrupted the folding of the protein as assayed by intrachain disulfide bond formation (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The association of alternate or modified siderophores with bacterial virulence can be explained in many cases by enabling iron acquisition in the face of the siderocalin innate immune defense by utilization of ‘stealthy’ siderophores which can escape binding and, therefore, sequestration (Clifton et al., 2009). Therefore, defining the breadth of a siderocalin’s ligand specificity defines the effective range of this defense. Like human and murine Scn, Ex-FABP tightly binds the 2,3-catechol-type ferric siderophores Ent, BB and PaB, associated with enteric bacteria and Gram-positive bacilli, and fails to bind hydroxamate-type siderophores like alcaligin, aerobactin, exochelin, coprogen, DFO and rhizoferrin or the 3,4-catechol-type siderophore petrobactin. The structural similarities between Scn and Ex-FABP reveal that a similar recognition mechanism is used, combining electrostatic and cation-π interactions in the absence of tight shape complementarity, with similar constraints on binding (Hoette et al., 2008). Many pathogenic bacteria evade mammalian siderophore sequestration by using enzymes, encoded by the iroA gene cluster found in many pathogenic strains of Gram-negative enteric bacteria, to alter Ent by glucosylation. Unlike Scn, however, Ex-FABP is capable of binding FeMGE, with better affinities than the unglucosylated analog, a result that is readily explained by apparent structural differences in the calyces of Scn and Ex-FABP. This result may help to explain the interesting observation that diglucosyl-Ent (also salmochelin) is the major siderophore found in cultures of iroA-harboring strains of bacteria and not monoglucosylated forms (Bister et al., 2004; Fischbach et al., 2006a); the existence of MGE-binding siderocalins require the addition of a second carbohydrate moiety to evade general siderocalin interception. The presumed function of Ex-FABP as an antibacterial, functioning through iron sequestration, is further confirmed by the potent bacteriostatic effect of Ex-FABP on the growth of E. coli and B. subtilis in vitro. While Ex-FABP affinities for Ent and FeEnt are comparable or stronger than those of Scn, but more than ten-fold weaker comparatively for BB and FeBB (Abergel et al., 2006), the key binding property for sequestration may be the off-rate, reflecting the complex half-life, which we have, so far, been unable to measure directly. Therefore, differences in apparent dissociation constants may be compensated kinetically. Like Scn, the presence or absence of iron has a relatively modest affect on the affinity of Ex-FABP for siderophores (~two-fold for Ent and BB; ~16-fold for MGE). For Scn, the Ent/FeEnt affinity ratio is less than nine-fold (Abergel et al., 2008) and ~four-fold for a synthetic Ent analog, TRENCAM (Hoette et al., 2008), which was explained by the dominance of cation-π over Coulombic interactions in the recognition mechanism and the relative rigidity of these hexadentate chelators even in the absence of metal (Hoette et al., 2008).

Scn and Ex-FABP have both been reported to have effects on endogenous cellular processes such as apoptosis and differentiation, which, for Scn, have been explained by a role in transferrin-independent iron transport mediated by simple catechols rather than bacterial siderophores (Abergel et al., 2008; Bao et al., 2010). However, our results also show that Ex-FABP binds specific LPA isoforms and can act as an LPA ‘sensor’, in the classic sense of a molecule that receives and responds to a signal or stimulus, in this case through a ligand-induced conformational change. Therefore, these results combine to suggest the hypothesis that Ex-FABP alternately affects these processes by sequestering, transporting or sensing LPA. Ex-FABP would therefore achieve pleiotropic functionality through dual ligand specificities, unlike Scn which is structurally incapable of specific LPA binding. LPA (1- or 2-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate) are bioactive phospholipids with diverse biological functions in many cell types, acting through a series of G protein-coupled receptors (LPA1–5, GPR87 & P2Y5) to mediate differentiation, inflammation, immune function, oxidative stress, cell migration, smooth muscle contraction, apoptosis and development (Noguchi et al., 2009). LPA is found in serum and a variety of tissues, generated by phospholipases (A1 or A2), monoacylglycerol kinase, glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase and autotaxin; LPA is degraded by lipid phosphate phosphatases or LPA acyltransferase. LPA levels required to elicit responses differ considerably depending on the type of response and the nature of the responding cells or tissues. Aberrant LPA-signaling has been linked to cancer through, for example, the dysregulation of autotaxin or LPA receptors, which can lead to hyperproliferation contributing to oncogenesis and metastasis. In vivo, LPA is present as a mixture of saturated and unsaturated isoforms (16:0, 18:0, 16:1, 18:1, 18:2 & 20:4) that can have markedly different physiological effects through specificities for different receptors. LPA concentrations can reach micromolar in normal human serum (Xu et al., 1998) and roughly 10 μM in egg whites, mostly as 18:2 and 20:4 isoforms in the latter (Nakane et al., 2001). While we were unable to quantitate Ex-FABP/LPA affinities, the co-purification/co-crystallization behavior strongly suggests dissociation constants at least as good as micromolar. Proteins like sterol carrier protein-2 non-specifically transport a variety of lipid species, including LPA (Schroeder et al., 2007). However, Ex-FABP selects a very narrow range of LPA species (16:0, 18:0, 18:1) during recombinant expression, demonstrating a high order of specificity, making Ex-FABP the first extracellular LPA-specific binding protein identified and detailing a specific LPA recognition mechanism, important for understanding the trafficking of this signaling molecule. LPA may play a role as a critical growth factor as a component of hen egg whites (Morishige et al., 2007), suggesting that Ex-FABP may be sensing or transporting LPA in this milieu as well.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification of Ex-FABP

The entB gene (K-12 Gene Accession Number ECK0588) was ablated in the BL21(DE3)-RIL E. coli strain (Stratagene) using the TargetTron Gene Knockout System (Sigma) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The derived BL21(DE3)-RIL entB− cell line carries chloramphenicol and kanamycin resistance markers. The Ex-FABP gene (residues 23–178 of the precursor; NCBI reference sequence NP_990753.1) was cloned into the pET22b(+) vector (Novagen) between Msc I and Xho I in frame with the pelB leader to ensure periplasmic targeting of the protein product. All mutants (R26A/E149A/E150A, R101A/R112A and V48E) were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and were engineered with a thrombin cleavage site upstream of the C-terminal His6 purification tag. Transformed cultures, grown at 37°C to an OD600 of ~0.8 in Luria broth (LB) supplemented with 1 mM FeCl3 to support entB− growth, were induced with 1 mM IPTG and grown overnight at 25°C. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in 30 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 20% w/w sucrose and 1 mM EDTA, re-pelleted, resuspended in ice-cold 5 mM MgSO4 and incubated on ice for 15 minutes with gentle stirring. After a final pelleting, the resulting supernatant, representing the periplasmic fraction, was purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography using NiNTA resin (5Prime), eluting by cleavage with thrombin, and polished by SEC.

Crystallization and Structure Determination

Crystals of the Ex-FABP R26A/E149A/E150A mutant were grown by the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method at 4°C. The protein was mixed with excess FeEnt (EMC Microcollections), washed and concentrated over a 10 kD cutoff spin column. The protein, at 25 mg/ml, was mixed 1:1 with a reservoir solution of 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.5), 0.2 M sodium acetate, 10% v/v isopropanol and 22% w/w PEG 4000. Crystals of complex grew in approximately two months and were cryopreserved in mother liquor containing 20% v/v glycerol. Diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Light Source beamline 5.0.1 (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA) and reduced using d*TREK (Pflugrath, 1999). Initial phase information was determined by molecular replacement using an ensemble of lipocalin structures (PDB accession codes 1EW3 and 1YUP) in space group P212121, using the program PHASER (McCoy et al., 2007) as implemented in the CCP4i program suite (Potterton et al., 2003). Phases were improved by subsequent rounds of model building and refinement using COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and REFMAC (Murshudov et al., 1997). Structure validation was carried with the MolProbity server (Davis et al., 2007) and the RCSB ADIT server.

Qualitative Siderophore Binding Assays

Ligand-free Ex-FABP between 1–5 mg/ml was loaded with ten-fold excess iron-bound siderophore and was extensively washed with PBS through multiple rounds of ultrafiltration to remove any unbound siderophore. UV-VIS spectra of empty protein, loaded protein and siderophore alone were collected using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrometer (Thermo Scientific).

Bacterial Growth Inhibition Assays

For E. coli (strain BL21(DE3)-RIL) and P. aeruginosa (strain PAO1), M9 minimal media (5 ml) was inoculated with single colonies and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. Cells from these starter cultures were pelleted, washed twice in PBS and resuspended into 50 ml of fresh M9 minimal media. The cells were grown to an OD600 of 1.0 and diluted 10-fold into fresh M9 minimal media containing 10 μM protein and 10 μM FeCl3 for the controls. Cultures were incubated at 37°C for 18 hours and the OD600 was monitored using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). For B. subtilis (strain ATCC 6051), specific iron-free growth medium (Dertz et al., 2006) was inoculated with single colonies and incubated for 15 hours at 30°C. This preculture was used to inoculate 1.3 ml of iron-free medium, which was incubated at 30°C to an OD600 of 0.3 (corresponding to the start of log phase growth). The culture was then diluted 50-fold in iron-free medium and aliquoted into a 96-well plate (200 μl per well). The plates were sealed with Breathe-Easy membranes (Sigma) and incubated at 30°C in a Spectramax Plus384 microplate reader to monitor OD600 (Molecular Devices).

Cell Culture

Chondrocytes were obtained from six day old chick embryo tibiae as previously described (Descalzi Cancedda et al., 2002). Briefly, cells from cartilaginous bone were expanded as adherent dedifferentiated cells for two weeks. Hypertrophic chondrocytes were obtained from dedifferentiated cells and cultured in suspension in agarose-coated dishes for three to four weeks until a homogeneous population was obtained, where single isolated cells highly-expressed Ex-FABP. For assays, hypertrophic chondrocytes from suspension culture were collected, washed and grown for three days in serum free medium plus either 20 μCi of 55FeCl3 or 20 μCi of 55FeCl3 plus siderophore (Ent or pyochelin), added at a total iron:siderophore molar ratio of 1:1. For dedifferentiated cells, parallel cultures of adherent cells were stimulated with E. coli LPS (Sigma) at a concentration of 5 μg/ml in serum free medium. Culture supernatants were dialyzed against PBS, concentrated in Centriprep-10 ultrafilters (Amicon) and fractionated on Superdex 75 HR 10/30 SEC columns (GE Healthcare). Fractions were analyzed by scintillation counter to quantitate iron and Western blot to quantitate Ex-FABP.

Western Blot Analysis

Medium aliquots were loaded on a 15% SDS-PAGE. Electrophoresis was performed under reducing conditions. After electrophoresis, the gel was blotted onto a BA85 nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher and Schuell GmbH, Dassel, Germany) as previously described (Towbin et al., 1979), blocked with 5% non-fat cow milk in TTBS buffer (20 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20), washed several times with TTBS and incubated for two hours at room temperature with an affinity-purified rabbit anti-Ex-FABP antiserum as primary (Cancedda et al., 1996) and a conjugated HRP-anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) as secondary detection reagents.

Immunoprecipitation of Ex-FABP Siderophore Complexes

Supernatants from radioactive iron labeled cells were pre-cleared with control rabbit IgG for two hours followed by incubation with Pansorbin (Calbiochem, Novabiochem Corp, La Jolla, CA, USA) in PBS for 1 hour. Three of six replicate aliquots were incubated overnight with specific rabbit immunoglobulin for Ex-FABP and three aliquots with control rabbit IgG. Pansorbin in PBS was added and incubated with continuous shaking for two hours. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times with PBS and assayed for remaining radioactivity.

FQ Binding Assays

FQ by binding ferric siderophores to recombinant Ex-FABP was measured on either a Jobin Yvon fluoroLOG-3 fluorimeter or Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer. An absorbance spectrum and both an initial and final emission spectra were collected to determine optimal excitation (λexc = 281 nm) and emission (λem = 340 nm) wavelengths, with a 5 nm slit band pass for excitation and a 10 nm slit band pass for emission. Measurements were made at a protein concentration of 100 nM in TBS (pH = 7.4) plus 32 mg/ml ubiquitin (Sigma) and 5% DMSO; fluorescence values were corrected for dilution upon addition of substrate. Quenching data were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis of fluorescence response versus substrate concentration using a one-site binding model as implemented in DYNAFIT (Kuzmic, 1996).

Transesterification of Ex-FABP Extractions

Bound lipids were analyzed by mass-spec using the methodology described in (Watts and Browse, 2002). Briefly, purified Ex-FABP fractions (500 μg) were incubated in 1 ml methanol plus 2.5% v/v sulfuric acid for 1 hour at 80°C and then on ice for 10 minutes. Total lipids were extracted by adding 1.5 ml water plus 400 μl hexane. The organic phase was then separated and analyzed with a 30 × 0.25-mm Agilent J&W Scientific HP-5ms capillary column, using helium carrier gas, on Agilent 5975/6920 GC/MS instrumentation.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Ex-FABP is bacteriostatic through iron sequestration by siderophore binding

Ex-FABP binds an extended range of siderophores versus Siderocalin

The extended Ex-FABP calyx defines a second binding site for lysophosphatidic acid

Acknowledgments

We thank Carissa Perez and Marc Van Gilst for assistance with the lipid analyses. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI48675 to RKS and AI011744 to KNR) and the Ministero Università e Ricerca (PRIN), Italy.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 3SAO.

Supplemental information includes five figures and one movie and can be found with this article online.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abergel RJ, Clifton MC, Pizarro JC, Warner JA, Shuh DK, Strong RK, Raymond KN. The siderocalin/enterobactin interaction: a link between mammalian immunity and bacterial iron transport. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11524–11534. doi: 10.1021/ja803524w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abergel RJ, Wilson MK, Arceneaux JE, Hoette TM, Strong RK, Byers BR, Raymond KN. Anthrax pathogen evades the mammalian immune system through stealth siderophore production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18499–18503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607055103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åkerstrom B, Flower DR, Salier JP. Lipocalins: unity in diversity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1482:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki J, Inoue A, Okudaira S. Two pathways for lysophosphatidic acid production. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1781:513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao G, Clifton M, Hoette TM, Mori K, Deng SX, Qiu A, Viltard M, Williams D, Paragas N, Leete T, et al. Iron traffics in circulation bound to a siderocalin (Ngal)-catechol complex. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:602–609. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes HJ. Miscellaneous bacterial diseases. In: Calnek BW, Barnes HJ, Beard CW, McDougald LR, Saif YM, editors. Diseases of poultry. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; 1991. pp. 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bister B, Bischoff D, Nicholson GJ, Valdebenito M, Schneider K, Winkelmann G, Hantke K, Sussmuth RD. The structure of salmochelins: C-glucosylated enterobactins of Salmonella enterica. Biometals. 2004;17:471–481. doi: 10.1023/b:biom.0000029432.69418.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancedda FD, Dozin B, Rossi F, Molina F, Cancedda R, Negri A, Ronchi S. The Ch21 protein, developmentally regulated in chick embryo, belongs to the superfamily of lipophilic molecule carrier proteins. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:19060–19064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancedda FD, Malpeli M, Gentili C, Di Marzo V, Bet P, Carlevaro M, Cermelli S, Cancedda R. The developmentally regulated avian Ch21 lipocalin is an extracellular fatty acid-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20163–20169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermelli S, Zerega B, Carlevaro M, Gentili C, Thorp B, Farquharson C, Cancedda R, Cancedda FD. Extracellular fatty acid binding protein (Ex-FABP) modulation by inflammatory agents: “physiological” acute phase response in endochondral bone formation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79:155–164. doi: 10.1078/s0171-9335(04)70018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton MC, Corrent C, Strong RK. Siderocalins: siderophore-binding proteins of the innate immune system. Biometals. 2009;22:557–564. doi: 10.1007/s10534-009-9207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coudevylle N, Geist L, Hotzinger M, Hartl M, Kontaxis G, Bister K, Konrat R. The v-myc-induced Q83 lipocalin is a siderocalin. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41646–41652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, 3rd, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derewenda ZS. Rational protein crystallization by mutational surface engineering. Structure. 2004;12:529–535. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derewenda ZS, Vekilov PG. Entropy and surface engineering in protein crystallization. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:116–124. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905035237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dertz EA, Xu J, Stintzi A, Raymond KN. Bacillibactin-mediated iron transport in Bacillus subtilis. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:22–23. doi: 10.1021/ja055898c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descalzi Cancedda F, Dozin B, Zerega B, Cermelli S, Gentili C, Cancedda R. Ex-FABP, extracellular fatty acid binding protein, is a stress lipocalin expressed during chicken embryo development. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;239:221–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marco E, Sessarego N, Zerega B, Cancedda R, Cancedda FD. Inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis by ExFABP gene targeting. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:464–473. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong A, Xu X, Edwards AM, Chang C, Chruszcz M, Cuff M, Cymborowski M, Di Leo R, Egorova O, Evdokimova E, et al. In situ proteolysis for protein crystallization and structure determination. Nat Methods. 2007;4:1019–1021. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozin B, Descalzi F, Briata L, Hayashi M, Gentili C, Hayashi K, Quarto R, Cancedda R. Expression, regulation, and tissue distribution of the Ch21 protein during chicken embryogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2979–2985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundas J, Ouyang Z, Tseng J, Binkowski A, Turpaz Y, Liang J. CASTp: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W116–118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach MA, Lin H, Liu DR, Walsh CT. How pathogenic bacteria evade mammalian sabotage in the battle for iron. Nat Chem Biol. 2006a;2:132–138. doi: 10.1038/nchembio771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach MA, Lin H, Zhou L, Yu Y, Abergel RJ, Liu DR, Raymond KN, Wanner BL, Strong RK, Walsh CT, et al. The pathogen-associated iroA gene cluster mediates bacterial evasion of lipocalin 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006b doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604636103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flower DR. The lipocalin protein family: a role in cell regulation. FEBS Lett. 1994;354:7–11. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganfornina MD, Gutierrez G, Bastiani M, Sanchez D. A phylogenetic analysis of the lipocalin protein family. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:114–126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentili C, Tutolo G, Zerega B, Di Marco E, Cancedda R, Cancedda FD. Acute phase lipocalin Ex-FABP is involved in heart development and cell survival. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:683–689. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz DH, Holmes MA, Borregaard N, Bluhm ME, Raymond KN, Strong RK. The Neutrophil Lipocalin NGAL Is a Bacteriostatic Agent that Interferes with Siderophore-Mediated Iron Acquisition. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1033–1043. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz DH, Willie ST, Armen RS, Bratt T, Borregaard N, Strong RK. Ligand preference inferred from the structure of neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1935–1941. doi: 10.1021/bi992215v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin-Dubiard C, Pasco M, Molle D, Desert C, Croguennec T, Nau F. Proteomic analysis of hen egg white. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:3901–3910. doi: 10.1021/jf0529969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl M, Matt T, Schuler W, Siemeister G, Kontaxis G, Kloiber K, Konrat R, Bister K. Cell transformation by the v-myc oncogene abrogates c-Myc/Max-mediated suppression of a C/EBP beta-dependent lipocalin gene. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoette TM, Abergel RJ, Xu J, Strong RK, Raymond KN. The role of electrostatics in siderophore recognition by the immunoprotein Siderocalin. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17584–17592. doi: 10.1021/ja8074665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes MA, Paulsene W, Jide X, Ratledge C, Strong RK. Siderocalin (Lcn 2) Also Binds Carboxymycobactins, Potentially Defending against Mycobacterial Infections through Iron Sequestration. Structure (Camb) 2005;13:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmic P. Program DYNAFIT for the Analysis of Enzyme Kinetic Data: Application to HIV Proteinase. Anal Biochem. 1996;237:260–273. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manduca P, Descalzi Cancedda F, Tacchetti C, Quarto R, Fossa P, Cancedda R. Synthesis and secretion of Ch 21 protein in embryonic chick skeletal tissues. Eur J Cell Biol. 1989;50:154–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishige J, Touchika K, Tanaka T, Satouchi K, Fukuzawa K, Tokumura A. Production of bioactive lysophosphatidic acid by lysophospholipase D in hen egg white. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:491–499. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahlik MS, Fleming TP, McIntosh MA. Cluster of genes controlling synthesis and activation of 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid in production of enterobactin in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4163–4170. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.9.4163-4170.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakane S, Tokumura A, Waku K, Sugiura T. Hen egg yolk and white contain high amounts of lysophosphatidic acids, growth factor-like lipids: distinct molecular species compositions. Lipids. 2001;36:413–419. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0737-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi K, Herr D, Mutoh T, Chun J. Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and its receptors. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paesen GC, Adams PL, Harlos K, Nuttall PA, Stuart DI. Tick histamine-binding proteins: isolation, cloning, and three-dimensional structure. Mol Cell. 1999;3:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugrath JW. The finer things in X-ray diffraction data collection. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:1718–1725. doi: 10.1107/s090744499900935x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potterton E, Briggs P, Turkenburg M, Dodson E. A graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:1131–1137. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903008126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder F, Atshaves BP, McIntosh AL, Gallegos AM, Storey SM, Parr RD, Jefferson JR, Ball JM, Kier AB. Sterol carrier protein-2: new roles in regulating lipid rafts and signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:700–718. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to mitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Shen Z, Wiper DW, Wu M, Morton RE, Elson P, Kennedy AW, Belinson J, Markman M, Casey G. Lysophosphatidic acid as a potential biomarker for ovarian and other gynecologic cancers. JAMA. 1998;280:719–723. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.8.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman AW, Veerkamp JH. New insights into the structure and function of fatty acid-binding proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1096–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8490-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.