Abstract

The past decade has brought many innovations to the field of flow and image-based cytometry. These advancements can be seen in the current miniaturization trends and simplification of analytical components found in the conventional flow cytometers. On the other hand, the maturation of multispectral imaging cytometry in flow imaging and the slide-based laser scanning cytometers offers great hopes for improved data quality and throughput while proving new vistas for the multiparameter, real-time analysis of cells and tissues. Importantly, however, cytometry remains a viable and very dynamic field of modern engineering. Technological milestones and innovations made over the last couple of years are bringing the next generation of cytometers out of centralized core facilities while making it much more affordable and user friendly. In this context, the development of microfluidic, lab-on-a-chip (LOC) technologies is one of the most innovative and cost-effective approaches toward the advancement of cytometry. LOC devices promise new functionalities that can overcome current limitations while at the same time promise greatly reduced costs, increased sensitivity, and ultra high throughputs. We can expect that the current pace in the development of novel microfabricated cytometric systems will open up groundbreaking vistas for the field of cytometry, lead to the renaissance of cytometric techniques and most importantly greatly support the wider availability of these enabling bioanalytical technologies.

I. Introduction

Advances in conventional flow and image-assisted cytometry provide the instrumentation of choice for studies requiring quantitative and multiparameter analysis with a single cell resolution (Darzynkiewicz et al., 1999; Wlodkowic et al., 2010). The advancements in conventional cytometric technologies can be easily seen in the current miniaturization trends and substantial simplification of analytical components (Shapiro, 2004). Technological milestones have already brought flow cytometry (FCM) out of centralized core facilities while making it much more affordable and user friendly. These trends will surely drive the renaissance of cytometry and growing interest in cytometric techniques worldwide (Shapiro, 2004; Wlodkowic et al., 2010).

Although the present array of conventional technologies has delivered many options and innovative solutions, there are still numerous areas for technological improvements (Eisenstein, 2006; Melamed, 2001). Not surprisingly, many new enabling strategies that can reduce expenditures while at the same time increase portability, throughput, and content of collected information are attracting growing interest among both academic and industrial markets (Hill, 1998). The improvements in such capabilities are of particular importance for the development of personalized therapeutic approaches (point-of-care diagnostics) and the increasing role of cost and time savings in drug discovery pipelines (Hill, 1998; Kiechle and Holland, 2009; Mayr and Bojanic, 2009; Myers and Lee, 2008).

In this context, the transfer of traditional bioanalytical methods to a microfabricated format can greatly facilitate the reduction of drug screening expenditures (Andersson and van den Berg, 2004; Chung and Kim, 2007; Kiechle and Holland, 2009). Microfabricated technologies can also vastly increase throughput and content of information from a given sample (Svahn and van den Berg, 2007; Whitesides, 2006). Advances in physics, electronics as well as material sciences have recently facilitated the development of miniaturized bioanalytical systems collectively known as lab-on-a-chip (LOC) (Andersson and van den Berg, 2004; Dittrich and Manz, 2006; Sims and Allbritton, 2007). LOC represents the next generation of analytical laboratories that have been miniaturized to the size of a matchbox, and represent one of the most groundbreaking offshoots of nanotechnology, delivering, among others, platforms for high-throughput drug discovery and content-rich personalized diagnostics (Mauk et al., 2007; Myers and Lee, 2008; Wang et al., 2009; Weigl et al., 2008; Whitesides, 2006). By providing an alternative to expensive instrumentation such as flow or laser scanning cytometers and sorters, while offering new functionalities, user-friendly LOC technologies can prospectively enable development of bench-top or even highly portable cytometers of the size of the modern notebooks or even mobile phones (Chung and Kim, 2007; Huh et al., 2005; Myers and Lee, 2008; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010c). Based on the progress in the field of LOC, we envisage that in a couple of years from now the microflow cytometers may well be as ubiquitous as standard PCR thermocyclers.

Attempts providing such groundbreaking capabilities have already been made and microfluidic chip-based cytometry is slowly entering a commercial stage with appearance of portable devices capable of multiparameter fluorescent interrogation. In this chapter we will discuss some of the selected and innovative microflow technologies nearing the commercial stage. Some of them are particularly attractive for the basic research, clinical and diagnostic laboratories as they allow rapid analysis of only small numbers of patient-derived cells. As such these can be particularly suitable for point-of-care diagnostics and distributed telemedicine (Kiechle and Holland, 2009; Myers and Lee, 2008; Weigl et al., 2008).

II. The Smaller the Better: Microfluidics and Enabling Prospects for Single Cytomics

Microfluidics is an emerging field of engineering aimed at manipulating liquids in networks of microchannels with dimensions between 1 and 1000 μm (Fig. 1). The dimensionless parameter called the Reynolds number (Re) describes unique physical principles of the fluid in micrometer-sized channels as a function of the geometry, fluid viscosity, and average flow rates (Sia and Whitesides, 2003; Whitesides, 2006). As described by the Re, the fluids at the microscale exhibit dissimilar physicochemical properties, when compared to their behavior at the macroscale (Holmes and Gawad, 2010; Pfohl et al., 2003; Polson and Hayes, 2001). For example, fluids at the microscale are largely dominated by viscous rather than inertial forces. This means that fluid flow in microchannels is laminar. Under laminar conditions, the fluid flow has no inertia and mass transport will be dominated by local diffusion rates (Beebe et al., 2002; Franke and Wixforth, 2008; Kastrup et al., 2008). As such convective contributions to mixing can be negated, and the supply of nutrients, gases, and drugs to cells can be spatiotemporally controlled that is aliquots of fluid can be delivered to particular positions at controlled timings (Takayama et al., 2001, 2003). Most importantly, however, the dimensions of microfluidic environment are comparable to the intrinsic dimensions of cells and blood vessels (Fig. 1) (Irimia and Toner, 2009; Liu et al., 2009; Stroock and Fischbach, 2010; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010c). Therefore, gas and drug diffusion rates, shear stress, and even microscale cellular niches can be artificially recreated on chip, mimicking the physiological microenvironment encountered in the human body (Warrick et al., 2008; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010c).

Fig. 1.

The design of miniaturized LOC technologies is a promising avenue to address the inherent complexity of cellular systems with massive experimental parallelization, throughput, and analysis on a single cell level. (A) Microfluidics is an emerging field of engineering aimed at manipulating ultralow volumes of liquids in networks of microchannels with dimensions between 1 and 1000 μm. Fluid flow in microfluidic channels is dominated by viscous rather than inertial forces. Laminar flow describes the conditions where all fluid particles move in parallel to the flow direction. Note that during microfluidic circuitry is dominated only by a limited and local diffusion. Miniaturization of LOC promises greatly reduced equipment costs, simplified operation, increased sensitivity, and throughput by implementing many innovative and integrated on-chip analytical modules. (B) Microfabrication allows for design of new analytical functionalities. These for instance enable immobilization, manipulation, treatment, and analysis of single cells. An example of microcage (microjail) structure is shown that allows for micromechanical trapping and immobilization of single human cells.

The enclosed and sterile format of microfluidic circuitry eliminates the evaporative water loss from microsized channels (Fig. 1) (Beebe et al., 2002; Berthier et al., 2008a, b; Wlodkowic et al., 2009a). Inexpensive and biocompatible polymers such as poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) are often materials of choice for rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices (Sia and Whitesides, 2003; Weibel and Whitesides, 2006; Zaouk et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2009). Glass, silica, or thermoplastics such as, for example, acrylic (poly(methyl methacrylate; PMMA) are on the other hand common substrates found in commercial chip-based designs (Fig. 1) (Pugmire et al., 2002; Qi et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2009). The latter technologies enhance the durability and application range to reusable and/or high-pressure applications. The disposable format of many LOC devices is particularly suitable for the point-of-care diagnostics and future personalized therapy. LOC devices also promise greatly reduced costs, increased sensitivity, and ultrahigh throughput by implementing parallel sample processing and a vast miniaturization of integrated on-chip components (Fig. 1) (Holmes and Gawad, 2010; Mauk et al., 2007; Michelsen, 2007; Myers and Lee, 2008; Weigl et al., 2008; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010d).

III. Microflow Cytometry (μFCM)

Conventional FCM is a powerful analytical and diagnostic tool that provides the multiparameter and high-speed measurements of cells 3D focused into a single file and integrated fluorescence from every cell collected by photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) (Mach et al., 2010; Melamed, 2001; Shapiro, 2004). FCM overcomes a frequent problem of traditional bulk techniques. Its advantages include the correlation of different cellular events at a time, single cell analysis (the avoidance of bulk analysis), and measuring thousand of cells per second. It suffers, however, from high cost, complex operation, and very limited portability (Mach et al., 2010; Melamed, 2001). Inherent limitations of traditional FCM have recently stimulated the fast development of chip-based microfluidic cytometers (Bhagat et al., 2010b; Cheung et al., 2010; Chung and Kim, 2007; Oakey et al., 2010; Skommer et al., 2010; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010d; Wlodkowic et al., 2010).

Application of microfluidic technologies can supplant many of the conventional disadvantages through the development of on-chip μFCM (Cheung et al., 2010; Chung and Kim, 2007; Huh et al., 2005). The major advantage of μFCM is that they sample a greatly reduced number of cells when compared with conventional FCM (Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010a; Wlodkowic et al., 2009c, 2010). This is of a particular value when studying, for example, rare, patient-derived cells and monitoring their reactions with therapeutic compounds (Wlodkowic et al., 2009c). Recent progress has opened many innovative opportunities to obtain confinement and regulation of laminar streams of cells in two or even in three dimensions thus miniaturizing the bulky 3D flow cells associated with conventional FCM (Kummrow et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2009; Mao et al., 2009; Scott et al., 2008). Some progress in sheath-free microcytometers that create ordered streams of cells has also been reported. Similarly to a conventional system, single file of cells on μFCMs can be sequentially interrogated by independent lasers providing substantial multiplexing opportunities. Moreover, the enclosed, sterile, and disposable nature of microfluidic circuitry makes μFCMs particularly suitable for the analysis of highly infective samples. This may be of particular importance during monitoring of HIV infections in resource poor areas.

Interestingly, apart from a mushrooming number of academic publications, microfluidic chip-based cytometry is slowly entering a commercial stage. The arrival of user-friendly, reasonably priced, and portable devices capable of multiparameter fluorescent analysis based on microfluidic principles heralds a sudden change in the field (Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010a, c). Examples include a multitude of experimental prototypes with flow rates controlled either by step motor-driven syringe pumps, positive air pressure applied to input reservoirs, or vacuum applied to output reservoirs of the microfluidic chips fabricated in polymers or glass (Chan et al., 2003; Palkova et al., 2004). While in the conventional flow cytometers the transfer rates through the flow chamber can be as high as 104–106 cells/s, most microfluidic planar chips maintain much lower transfer rates of 10–300 cells/s (Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010a, d; Wolff et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2010). The reduced transfer rates can be, in turn, effectively compensated for by parallel processing and simultaneous analysis of multiple and parallel streams of cells on each chip (Hur et al., 2010; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010a, c). Low transfer rates and pressures are also advantageous for preservation of living cells. In this regard, some of the most recent innovations in the μFCM chip design facilitate also the collection of an undiluted cell population for many functional studies to be performed following the microcytometric analysis. This feature is not available in any of the conventional FCM systems apart from the complex fluorescently activated cell sorters.

The most notable examples of commercial stage μFCM involve the CellLab Chip (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Fishman-R (On-chip Biotechnologies Co., Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 2 A, B). CellLab chip was the first commercially available microcytometry system utilizing disposable glass chips (cartridges) based on patented Caliper LabChip® technology (Fig 2 A, B). The microfluidic cartridges are run by a modified Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) (Chan et al., 2003; Palkova et al., 2004). This technology allows for simultaneous analysis of up to six independent samples with a throughput of about 2.5 cells/s (Chan et al., 2003; Palkova et al., 2004). It provides a very low cell consumption and complete automation that alleviates laser aligning and operator engagement. The optical configuration of the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer features two excitation light sources (LED 525 nm and solid state laser 685 nm) (Chan et al., 2003). Substantial fluorescence signal separation between emission channels (FL1 Em 525 nm vs. FL2 Em 685 nm) alleviates need for any spectral compensation. In our recent work we have proven that sensitivity of Caliper LabChip® technology is adequate to detect subtle changes in fluorescence intensity during two color microcytometric analysis of drug-induced apoptosis (Wlodkowic et al., 2009c).

Fig. 2.

Innovative microfluidic flow cytometers (μFCM). (A) (B) Overview of the Agilent CellLab Chip technology. A glass chip with an etched network of microfluidic channels is mounted into the plastic cartridge providing the interface for the modified Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Note the principles of microcytometry such as microhydrodynamic cell focusing using isobuoyant sheath buffer and double-point laser interrogation point (right panel). Systems permit for an automated, clog-free operation. No laser alignment or operator engagement is necessary for a sequential analysis of up to six samples on one chip. (C) Disposable microfluidic cartridge of the Fishman-R microfluidic flow cytometer with a two-way 2D hydrodynamic focusing of cells. (D) Optical configuration of Fishman-R microfluidic flow cytometers. Multiparameter detection capabilities are comparable to the conventional flow cytometers. Note forward scatter (FSC), side scatter (SSC), and four fluorescence detectors used in combination with spatially separated solid state 473 and 640 nm solid-state diode lasers. Side scatter detection is performed using innovative SLER technology (side scattered light detection using edge reflection) recently developed by On-chip Biotechnologies Co. (Tokyo, Japan). (E) Off-chip interface of the Fishman-R microfluidic flow cytometer housing the pneumatic and optical modules (data courtesy of Dr Kazuo Takeda, On-chip biotechnologies Co., Tokyo, Japan). (F) Multicolor immunophenotyping performed on the microfluidic Fishman-R flow cytometer as compared to conventional flow cytometers. Note that μFACS analysis requires merely 20 μl of blood and yields comparative multiparameter data to FACS (data courtesy of Dr Kazuo Takeda, On-chip Biotechnologies Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Fishman-R is on the other hand an example of a quantum leap in the development of μFCM (Fig 2C-F) (Takeda and Jimma, 2009; Takao et al., 2009). The system developed by the group of Takeda at On-chip Biotechnologies (Tokyo, Japan) introduces for the first time a fully fledged and user friendly microcytometer with (i) 2D hydrodynamic sheath focusing, (ii) multi-laser excitation, (ii) up to four color detection, and (iv) detection with fluorescence area, height, and width parameters for all fluorescent channels (Fig 2C-F) (Takeda and Jimma, 2009; Takao et al., 2009). Sensitivity of this microfluidic cytometer is well within specifications of conventional analyzers (i.e., FITC <600 MESF, PE <200 MESF). Fishman-R is also the first microflow cytometer that incorporates true Forward Site Scatter and Side Site Scatter detection (Fig 2C-F) (Takeda and Jimma, 2009; Takao et al., 2009).

Current progress in on-chip cytometry leverages advances in microfluidic technologies with the ultimate outcome to produce user friendly, reasonably priced and portable devices (Takeda and Jimma, 2009; Takao et al., 2009). They are particularly attractive for the clinical and diagnostic laboratories. Based on the progress in the field of LOC, one can already envisage that in a couple of years from now the microflow cytometers may well be as ubiquitous as standard PCR thermocyclers (Fig 2E).

IV. Microfluidic Cell Sorting (μFACS)

The accurate detection, analysis, and sorting of defined cell subpopulations is of importance not only for basic and clinical research but also for biotechnology and agriculture (Eisenstein, 2006; Melamed, 2001). In this respect, conventional FCM still remains the technology of choice with an array of high-speed fluorescently activated cell sorters (FACS) available on the market. Indeed, modern FACS have an impressive capabilities that support algorithms based on up to 16 optical parameters measured from a single cell and enormous acquisition rates that exceed 2.5 × 104 events/s (Eisenstein, 2006; Melamed, 2001). The deployment of FACS is, however, currently limited to only centralized core facilities. This is mostly due to their high complexity, power consumption, and resulting intrinsic cost of the equipment. The need for specialized and dedicated personnel capable of operating these machines is also yet another limiting factor that restricts widespread access to this technology (Eisenstein, 2006).

Not surprisingly, there is an increasing interest and demand for cost-effective cell sorting systems that could supplement conventional FCM. In this context microfluidics has an immense potential to meet these demands, due to the inherent ease of rapid prototyping, potential of flexible and scalable designs, enhanced analytical performance and economical fabrication. Numerous emerging microfluidic cell sorting devices have been designed, and are based on various cell sorting principles such as piezoelectrical actuation, dielectrophoresis (DEP), magnetophoresis, optical gradient forces, and hydrodynamic flow switching (Adams et al., 2008; Adams and Tom Soh, 2009; Arndt-Jovin and Jovin, 1974; Baret et al., 2009; Bhagat et al., 2010a; Gluckstad, 2004; Kuntaegowdanahalli et al., 2009; Revzin et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010a; Wolff et al., 2003).

Only recently, several microfluidic FACS (μFACS) have been proposed. They have mostly suffered, however, from low throughput, lack of integrated mechanisms for actuation, poor sensitivity of fluorescence detection, and low sorting accuracy as compared to the conventional FACS. Recent innovations made in the field seem, however, to alleviate most of these dilemma and pave the way for the development of fully integrated and automated microsorters. In this context, recent work of Cho and colleagues introduced a new design with microfluidic, as well as optical, acoustical, and piezoelectronic components, all embedded into a single chip (Cho et al., 2010). This superior design features also a new automated sorting control system and a signal processing algorithm (“space-time coding technology”) that permit high-speed sorting of particles combined with a superior purification enrichment factors (Cho et al., 2010).

The multiple sample processing procedures are often required during conventional FACS that decrease the efficiency and make separation of clinically relevant rare subpopulations challenging. High pressures and electrostatic charges used to deflect sorted cells can further affect the recovery of fragile cell subpopulations such as apoptotic cells and cancer stem cells. At the same time large-size conventional equipment coupled with complex fluidic technologies are major impediments for the development of clinical grade sorting. Also undesired aerosol formation usually associated with conventional FACS often preclude safe sorting of highly infectious specimens without dedicated containment rooms necessary for biohazard FACS sorting. Most recently, an innovative μFACS system has been commercialized that provides a new solution to the above-mentioned problems. The Gigasort™ Clinical Grade Cell Sorter developed by the CytonomeST LLC (Boston, MA, USA) is the fastest fully sterile optical cell sorter ever produced and can be named as the most revolutionary advancement in FACS since its invention in early 1960s. It employs fully enclosed, disposable chip sorting cartridges that enable gentle, clinical grade, sterile sorting without any undesired side-effects of the procedure (Fig. 3). As such clinical-grade cell sorting can be performed that was not possible with other solid or flow-based cell sorting methods. Importantly, the Gigasort’s enclosed and disposable cartridges support all staining protocols developed for conventional FCM with up to two optical (extinction and side scatter) and seven simultaneous fluorescent parameters from each cell. In the heart of this groundbreaking technology lies a system of innovative microfluidic particle switches used to deflect and sort cells in the microchannels (Fig. 3). The switch (microsorter) operates at a rate of 2000 cell sorting operations per second. By leveraging the potential for modular design, Gigasort™ increases the throughput by using a parallel sample processing paradigm well known in the microprocessor industry (Fig. 3). Using a massively parallel array of up to 72 concurrently operating microfluidic sorter cores, the technology achieves ultra-high sorting speeds of up to 1 billion events/h. The 72 microfluidic switches have been fabricated onto a single glass chip that measures 2 × 3 in. (Fig. 3). Reportedly, the single 72 channel chip can sort up to 1 × 105 cells/s (0.5 × 109 cells/h) and can operate at over seven times the throughput of any conventional FACS. According to CytonomeST data, the new generation of the Gigasort sorters will boast the configuration of up to 144 sorter cores reaching the combined sorting speed of up to 2.8 × 105 cells/s (1.0 × 109 cells/h). To support such ultra-high throughput, the Cytonome’s cartridges exceed 2 billion cells capacity that is optimized for a sample concentration of 5 × 106/ml.

Fig. 3.

Gigasort™ Clinical Grade Cell Sorter (CytonomeST LLC, Boston, MA, USA) is the fastest fully sterile optical cell sorter ever produced and can be named as the most revolutionary advancement in FACS since its invention in the early 1960s. (A) A microfabricated glass die measuring 2 × 3 inches and containing 72 parallel microfluidic switches (microsorters). Using a massively parallel array of simultaneously operating microfluidic sorter cores, the technology achieves ultra-high sorting speeds of up to 1 billion events per hour. As such it can operate at over seven times the throughput of any conventional FACS. (B) Early prototype of Gigasort™ Clinical Grade Cell Sorter. (C) Principles of Gigasort operation. Each switch (microsorter) operates in sequential steps at a rate of 2000 cell sorting operations per second. In Step 1, cells pass through the microfluidic channel. In Step 2, laser beams illuminate the cells and optical emission occurs. In Step 3, emission is analyzed and accept/reject sort decisions are made by the off-chip hardware and software modules. In Step 4, microactuator pushes the diaphragm that moves the sorted cell into the upper portion of the laminar fluid stream. In Step 5, the desired cell (green) is moved into the keep area, whereas non-sorted cells (red) are directed to waste compartment. Data courtesy of Dr John C Sharpe, CytonomeST LLC (Boston, MA, USA). (See plate no. 7 in the color plate section.)

We expect many new microfabricated cell sorters coming up to the market during next couple of years. Considering the advantages and simplicity of the on-chip cell sorting protocols, these platforms have a wide potential to be used for automated diagnostic and laboratory routines. Similarly to the μFCM, we anticipate that rapid advances in microfluidics, electronics, miniaturized optical components, micron tolerance mechanics and control algorithms will bring fluorescently activated cell sorting out of the centralized core facilities and onto the benches of regular biomedical laboratories.

V. Real-Time Cell Analysis: Living Cell Microarrays and a Real-Time Physiometry on a Chip

A common drawback of both conventional FCM and μFCM is that the cells flow suspended in a laminar stream of fluid and fluorescence is collected by PMTs or photodiodes without collecting the valuable information on subcellular and morphological features (Skommer et al., 2010; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010b, c; Wlodkowic et al., 2009d, 2010). Moreover, flow cytometric analysis suffers from a lack of capabilities to monitor single living cells in real time (dynamic analysis) and as such still represent a binary system that averages the results by capturing only a snapshot of the intermittent cellular reaction at a particular point in time (Skommer et al., 2010; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010c). Cellular processes, however, are dynamic and feature very large cell-to-cell variations. Moreover, the majority of cellular events have highly ordered interactions not only between different intracellular compartments but also between the neighboring cells (Skommer et al., 2010; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010a, b). Monitoring of these biological phenomena at a single cell level requires real-time and spatial detection systems with a micrometer scale resolution (Faley et al., 2009; Skommer et al., 2010; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010b, d; Wlodkowic et al., 2009b).

These drawbacks of microflow-based methods have recently led to the development of new LOC technologies with an attempt to transfer cell culture and real-time cell assays to a format commonly known as living cell microarrays (Di Carlo et al., 2006; Situma et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Wheeler et al., 2005; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010b; Yarmush and King, 2009). Cell microarrays in general allow creating positioned arrays composed of highly miniaturized cell culture. These unique LOC systems can be easily integrated with imaging or laser-scanning cytometers. Unlike FCM, measurements are made at multiple time points, and in contrast to conventional time-lapse microscopy, image analysis is greatly simplified by arranging the cells in a spatially defined pattern and/or by their physical separation (Di Carlo et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010b, d; Wlodkowic et al., 2009b; Yarmush and King, 2009). Cell microarrays are scalable for massively parallel processing and as such they are ideal for drug screening routines. They also have the ability to perform kinetic and multivariate analysis of signaling events on a single cell level. Thus, cell microarray technology seems to be particularly suitable to uncover intricacies in cell-to-cell variability (Skommer et al., 2010; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010b, c; Wlodkowic et al., 2009b, 2010).

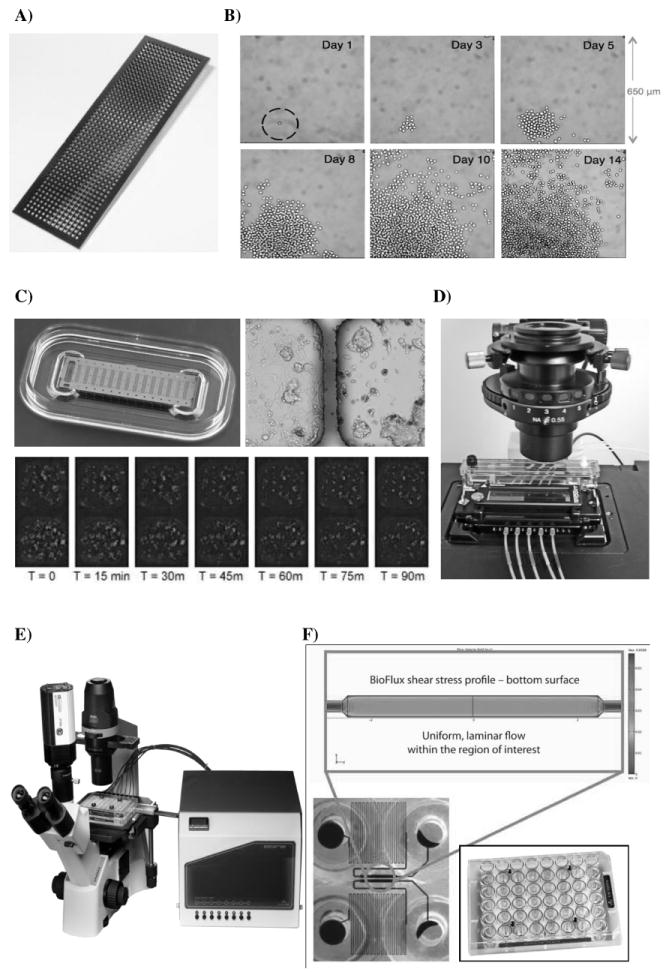

Successful attempts have been made to provide high-density living cell arrays in both static and microperfusion formats and several interesting commercial designs have already reached the market. Picovitro plates (Picovitro AB, Stockholm, Sweden) are one of the examples of static cell microarrays where cells can be seeded, cultivated, and treated in microwells with sizes of the order of 600 μm and the net volume of 500 nl (Fig. 4A) (Lindstrom and Andersson-Svahn, 2010; Lindstrom et al., 2009c). This cell microarray design utilizes glass bottom with a silicon microgrid that forms the walls of the wells (Lindstrom et al., 2009a, 2009b, 2009c). A top level semi-permeable PDMS membrane is added after cell seeding that seals the array from external world. PDMS membrane facilitates efficient gas diffusion but profoundly limits the evaporative water loss (Lindstrom et al., 2009a). These high-density microplates reportedly allow long-term and simultaneous culture in 3243 microwells vastly increasing the assay throughput while being compatible with conventional liquid handling protocols (Fig 4B).

Fig. 4.

High-throughput drug screening on innovative microfabricated chips. (A) Picovitro microarray plates and slides as an example of a proprietary, microfabricated high-density cell array. Microwells 650 × 650 μm are fabricated by anodically bonding the silicon grid wafer to a 500 μm borofloat glass substrate (left panel). (B) Example of a long-term cell proliferation analysis on a Picovitro array. Long-term clone formation was started with a single K-562 cell FACS sorted to one well and cultured for up to 2 weeks. Data courtesy of Dr Sara Lindström, Picovitro AB (Stockholm, Sweden). (C) (D) CellTRAY®–a novel micro-etched live cell screening technology. Independently addressable regions of glass or plastic microwells allow for a multiplexed and time-resolved experimentation at a single cell level. Fully integrated and automated CellTRAY® system mounted on a microscope stage. On-microscope incubator and integrated microfluidics system allow for long-term experiments with automated, precise time-lapse imaging of live cells over the course of several days. Data courtesy of Dr Cathy Owen, Nanopoint Inc. (Honolulu, HI, USA). (E) (F) The BioFlux System (Fluxion Biosciences, San Francisco, CA, USA) that provides the state-of-the-art ability to emulate the physiological shear flow in an in vitro model. Shear force, flow rates, temperature, and compound addition, however, can be independently controlled and automated through the dedicated software. The BioFlux system leverages the advantages of microfluidics to create a network of laminar flow cells integrated into standard microtiterwell plates to ensure compatibility with common microscope stages making it thus compatible with bright field, fluorescence, confocal microscopy, and possibly also laser scanning cytometry. Data courtesy of Dr Mike Schwartz, Fluxion Biosciences (San Francisco, CA, USA).

The precise delivery and exchange of reagents using static cell microarrays still requires macroscale liquid handling equipment. Most important, it does not allow for a precise spatiotemporal control over the artificial microenvironment on a chip (Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010a, b; Yarmush and King, 2009). Microfluidic cell arrays provide here a considerable technological improvement over static microarrays that allow for fabrication of parallelized and fully addressable arrays (Di Carlo et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Yarmush and King, 2009). In contrast to static cell microarrays, the constant microperfusion under low Reynold numbers facilities physiologically relevant exchange of stimulants and metabolites. Furthermore, the straightforward computer-aided design (CAD) of microfluidic chips and computational modeling of their fluid mechanics supports the precise control over the microenvironment surrounding growing cells. As a result, microfluidic cell arrays are ideally positioned for studies on real time and spatiotemporal control of cell behavior to changing microenvironment, a feature not attainable with any static technologies (Di Carlo et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010b, c; Wlodkowic et al., 2009b; Yarmush and King, 2009).

An interesting proprietary design of perfusion array technology has recently been introduced by the Nanopoint Inc. (Honolulu, HI, USA) under the trademark of CellTRAY® (Fig 4C, D). CellTRAY® consists of independent subregions of glass or plastic microwells that allow for a multiplexed, time-resolved imaging of single cells (Fig 4C). Apart from the innovative chip design, Nanopoint Inc. provides also fully integrated and automated control hardware and software that is user friendly and reportedly can be installed within minutes (Fig 4D). Microchip and integrated microfluidics control system can be mounted on an inverted microscope stage and allow for long-term experiments with time-lapse imaging of live cells over the course of several days (Fig 4C, D).

Many conventional assays do not incorporate physiological processes that are normally encountered by cells/tissues in the human body, such as microperfusion, gas/drug diffusion rates and shear stress (Hallow et al., 2008; Schaff et al., 2007). These design limitations of macroscale analytical systems have led to biased understanding of many transient and intermittent physiological processes. This is often reflected by failure of many therapeutic leads, selected after in vitro screening, to perform in vivo in animal models. In this context, another noteworthy commercial technology for automated real-time analysis under shear flow has recently been proposed by Fluxion Biosciences (San Francisco, CA, USA) (Fig 4E). The BioFlux System is a versatile platform for conducting cellular interaction assays which overcomes the limitations of static well plates and conventional laminar flow chambers (Fig 4E, F). The system provides the state-of-the-art ability to emulate the physiological shear flow in an in vitro model (Fig 4F). It leverages the advantages of microfluidics to create a network of laminar flow cells integrated into standard microtiterwell plates to ensure compatibility with common microscope stages making it thus compatible with bright field, fluorescence, confocal microscopy, and possibly also laser scanning cytometry (Fig 4E, F). Shear force, flow rates, temperature, and compound addition, however, can be independently controlled and automated through the dedicated software. The microfluidic environment closely mimics the physiological microenvironment, including gas and drug diffusion rates, shear stress, and cell confinement. In the context of, that is, tumor, vascular, developmental, and stem cell biology, the BioFlux system warrants a major “quantum leap” for the improved drug discovery pipelines.

Other emerging microfluidic technologies provide innovative ways to simultaneously analyze large population of living cells whereby the position of every single cell is encoded and spatially maintained over extended periods of time (Fig. 5) (Di Carlo et al., 2006; Rettig and Folch, 2005; Revzin et al., 2005; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010b; Wlodkowic et al., 2009b; Wood et al., 2010; Yarmush and King, 2009). The main advantage of positioned cell arrays lies in the ability to study the kinetic multivariate signaling events on a single cell level, which is particularly useful for analysis of cell-to-cell variability and its relevance to cancer therapy (Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010b; Wlodkowic et al., 2009b). Many single cell immobilization designs have recently been explored that include static microwells, DEP, as well as micromechanical, chemical, and hydrodynamic cell trapping (Di Carlo et al., 2006; Jang et al., 2009; Lan and Jang, 2010; Rettig and Folch, 2005; Revzin et al., 2005; Thomas et al., 2009; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010b; Wlodkowic et al., 2009b; Wood et al., 2010). Most recently, the noteworthy reports have proposed hydrodynamic positioning and immobilization of single cells in arrays of micromechanical traps, designed to passively cage individual non-adherent cells (Fig. 5). They reportedly allow for rapid trapping of cells in low shear stress zones while being continuously perfused with drugs and sensors (Di Carlo et al., 2006; Faley et al., 2009; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010b; Wlodkowic et al., 2009b). The density and cell trapping efficiency can be easily tailored by changing the number and geometry of microjails (Fig. 5). These emerging techniques create a living single cell and dynamic arrays, ideal for modeling cellular microenvironment and inherently scalable for high-throughput screening (Faley et al., 2009; Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010b, c; Wlodkowic et al., 2009b; Yarmush and King, 2009).

Fig. 5.

Living cell microarrays. (A) Single cell microarray platform fabricated in a glass substratum using femtosecond pulse laser μ-machining. Static cell microarray allows for a single cell docking into an array of microfabricated wells. Single wells are 25 μm in diameter. Cells passively sediment into a predefined pattern and are inaccessible to neighboring cells. This minimizes the influence of extrinsic factors, such as physical cell-to-cell contacts and paracrine signaling. This design facilitates real-time analysis at both single cell and population level. (B) Design of the microfluidic cell array (microfluidic array cytometer) with an active (hydrodynamic) cell docking into an array of microfabricated cell traps (microjails). Note the triangular chamber that contains a low-density cell positioning array. Array of microjails was fabricated in a biocompatible elastomer, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), and bonded to a glass substrate. The microfluidic array cytometer allows for a gentle trapping of single live cells for prolonged periods of time. (C) Principles of hydrodynamic cell docking and continuous microperfusion on a microfluidic array cytometer.

VI. Conclusions

Microfluidic LOC technologies emerge as relatively uncomplicated and effective solutions for modern cytometry and single cytomics (Wlodkowic and Cooper, 2010a, b). Most importantly, they often provide functionalities and sensitivity that often cannot be easily achieved with any conventional analytical platforms. There is a reason to believe that progress in novel LOC technologies is just a prelude to the major transformation of the field of cytometry. There are still key challenges that lie ahead and include on-chip integration and simplification of many functional components. Robust incorporation within the clinical and research laboratory infrastructure and standardization of innovative LOC cytometers will be an important step toward the rapid expansion of these enabling technologies. As discussed, the recent emergence on the market of user-friendly microscale equipment heralds arrival of the new era in the field of cytometry. We envisage that technologies described here will soon have direct implications for cost and time savings that play an ever increasing role in industrial drug screening pipelines. We anticipate that maturation of such microfluidic technologies in the form of user friendly and integrated enabling systems will attract a mounting interest from biopharmaceutical and academic communities, and will help to reduce drug development expenditures while increasing throughput and content of information.

Expectedly, we are also soon to witness the rise of even more innovative microtechnologies with vast potential in clinical and point-of-care diagnostics (Kiechle and Holland, 2009; Lee et al., 2010; Linder, 2007; Mansfield et al., 2006; Mauk et al., 2007; Ong et al., 2010; Sia and Kricka, 2008). Finally, based on the incredible progress in the field and looking beyond the next 10 years, we anticipate that a new generation of cytometers will prospectively employ microfluidic systems possibly with integrated on-chip cell culture, drug delivery, cytometric analysis and sorting modules. As such they will provide an all-in-one workstations for the future generations of cytometrists.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Foundation for Research Science and Technology NZ (FRST). Authors thank: Drs Kazuo Takeda from On-chip Biotechnologies Co. (Tokyo, Japan), John C Sharpe from CytonomeST LLC (Boston, MA, USA), Sara Lindström from Picovitro AB (Stockholm, Sweden), Cathy Owen from Nanopoint Inc. (Honolulu, HI, USA), and Mike Schwartz from Fluxion Biosciences (San Francisco, CA, USA) for sharing data and providing materials on proprietary micro-fabricated analytical systems.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicting financial interest.

References

- Adams JD, Kim U, Soh HT. Multitarget magnetic activated cell sorter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18165–18170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809795105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JD, Tom Soh H. Perspectives on utilizing unique features of microfluidics technology for particle and cell sorting. JALA Charlottesv Va. 2009;14:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jala.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson H, van den Berg A. Microtechnologies and nanotechnologies for single-cell analysis. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2004;15:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt-Jovin DJ, Jovin TM. Computer-controlled multiparameter analysis and sorting of cells and particles. J Histochem Cytochem. 1974;22:622–625. doi: 10.1177/22.7.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baret JC, Miller OJ, Taly V, Ryckelynck M, El-Harrak A, Frenz L, Rick C, Samuels ML, Hutchison JB, Agresti JJ, Link DR, Weitz DA, Griffiths AD. Fluorescence-activated droplet sorting (FADS): efficient microfluidic cell sorting based on enzymatic activity. Lab Chip. 2009;9:1850–1858. doi: 10.1039/b902504a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe DJ, Mensing GA, Walker GM. Physics and applications of microfluidics in biology. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2002;4:261–286. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.112601.125916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthier E, Warrick J, Yu H, Beebe DJ. Managing evaporation for more robust microscale assays. Part 1. Volume loss in high throughput assays. Lab Chip. 2008a;8:852–859. doi: 10.1039/b717422e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthier E, Warrick J, Yu H, Beebe DJ. Managing evaporation for more robust microscale assays. Part 2. Characterization of convection and diffusion for cell biology. Lab Chip. 2008b;8:860–864. doi: 10.1039/b717423c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat AA, Bow H, Hou HW, Tan SJ, Han J, Lim CT. Microfluidics for cell separation. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2010a;48:999–1014. doi: 10.1007/s11517-010-0611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat AA, Kuntaegowdanahalli SS, Kaval N, Seliskar CJ, Papautsky I. Inertial microfluidics for sheath-less high-throughput flow cytometry. Biomed Microdevices. 2010b;12:187–195. doi: 10.1007/s10544-009-9374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SD, Luedke G, Valer M, Buhlmann C, Preckel T. Cytometric analysis of protein expression and apoptosis in human primary cells with a novel microfluidic chip-based system. Cytometry A. 2003;55:119–125. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung KC, Di Berardino M, Schade-Kampmann G, Hebeisen M, Pierzchalski A, Bocsi J, Mittag A, Tarnok A. Microfluidic impedance-based flow cytometry. Cytometry A. 2010;77:648–666. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SH, Chen CH, Tsai FS, Godin JM, Lo YH. Human mammalian cell sorting using a highly integrated micro-fabricated fluorescence-activated cell sorter (microFACS) Lab Chip. 2010;10:1567–1573. doi: 10.1039/c000136h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung TD, Kim HC. Recent advances in miniaturized microfluidic flow cytometry for clinical use. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:4511–4520. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzynkiewicz Z, Bedner E, Li X, Gorczyca W, Melamed MR. Laser-scanning cytometry: A new instrumentation with many applications. Exp Cell Res. 1999;249:1–12. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo D, Wu LY, Lee LP. Dynamic single cell culture array. Lab Chip. 2006;6:1445–1449. doi: 10.1039/b605937f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich PS, Manz A. Lab-on-a-chip: microfluidics in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:210–218. doi: 10.1038/nrd1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein M. Cell sorting: divide and conquer. Nature. 2006;441:1179–1185. doi: 10.1038/4411179a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faley SL, Copland M, Wlodkowic D, Kolch W, Seale KT, Wikswo JP, Cooper JM. Microfluidic single cell arrays to interrogate signalling dynamics of individual, patient-derived hematopoietic stem cells. Lab Chip. 2009;9:2659–2664. doi: 10.1039/b902083g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke TA, Wixforth A. Microfluidics for miniaturized laboratories on a chip. Chemphyschem. 2008;9:2140–2156. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200800349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluckstad J. Microfluidics: sorting particles with light. Nat Mater. 2004;3:9–10. doi: 10.1038/nmat1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallow DM, Seeger RA, Kamaev PP, Prado GR, LaPlaca MC, Prausnitz MR. Shear-induced intracellular loading of cells with molecules by controlled microfluidics. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;99:846–854. doi: 10.1002/bit.21651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DC. Trends in development of high-throughput screening technologies for rapid discovery of novel drugs. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 1998;1:92–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes D, Gawad S. The application of microfluidics in biology. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;583:55–80. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-106-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D, Gu W, Kamotani Y, Grotberg JB, Takayama S. Microfluidics for flow cytometric analysis of cells and particles. Physiol Meas. 2005;26:R73–98. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/26/3/R02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur SC, Tse HT, Di Carlo D. Sheathless inertial cell ordering for extreme throughput flow cytometry. Lab Chip. 2010;10:274–280. doi: 10.1039/b919495a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irimia D, Toner M. Spontaneous migration of cancer cells under conditions of mechanical confinement. Integr Biol (Camb) 2009;1:506–512. doi: 10.1039/b908595e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang LS, Huang PH, Lan KC. Single-cell trapping utilizing negative dielectrophoretic quadrupole and microwell electrodes. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;24:3637–3644. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastrup CJ, Runyon MK, Lucchetta EM, Price JM, Ismagilov RF. Using chemistry and microfluidics to understand the spatial dynamics of complex biological networks. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:549–558. doi: 10.1021/ar700174g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiechle FL, Holland CA. Point-of-care testing and molecular diagnostics: miniaturization required. Clin Lab Med. 2009;29:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummrow A, Theisen J, Frankowski M, Tuchscheerer A, Yildirim H, Brattke K, Schmidt M, Neukammer J. Microfluidic structures for flow cytometric analysis of hydrodynamically focussed blood cells fabricated by ultraprecision micromachining. Lab Chip. 2009;9:972–981. doi: 10.1039/b808336c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntaegowdanahalli SS, Bhagat AA, Kumar G, Papautsky I. Inertial microfluidics for continuous particle separation in spiral microchannels. Lab Chip. 2009;9:2973–2980. doi: 10.1039/b908271a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan KC, Jang LS. Integration of single-cell trapping and impedance measurement utilizing microwell electrodes. Biosens Bioelectron. 2010;26:2025–2031. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.08.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Choi S, Park JK. Three-dimensional hydrodynamic focusing with a single sheath flow in a single-layer microfluidic device. Lab Chip. 2009;9:3155–3160. doi: 10.1039/b910712f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WG, Kim YG, Chung BG, Demirci U, Khademhosseini A. Nano/microfluidics for diagnosis of infectious diseases in developing countries. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder V. Microfluidics at the crossroad with point-of-care diagnostics. Analyst. 2007;132:1186–1192. doi: 10.1039/b706347d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom S, Andersson-Svahn H. Miniaturization of biological assays – Overview on microwell devices for single-cell analyses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1810:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom S, Eriksson M, Vazin T, Sandberg J, Lundeberg J, Frisen J, Andersson-Svahn H. High-density microwell chip for culture and analysis of stem cells. PLoS One. 2009a;4:e6997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom S, Hammond M, Brismar H, Andersson-Svahn H, Ahmadian A. PCR amplification and genetic analysis in a microwell cell culturing chip. Lab Chip. 2009b;9:3465–3471. doi: 10.1039/b912596e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom S, Mori K, Ohashi T, Andersson-Svahn H. A microwell array device with integrated microfluidic components for enhanced single-cell analysis. Electrophoresis. 2009c;30:4166–4171. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Li C, Li H, Zeng S, Qin J, Lin B. A microfluidic device for characterizing the invasion of cancer cells in 3-D matrix. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:4285–4291. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mach WJ, Thimmesch AR, Orr JA, Slusser JG, Pierce JD. Flow cytometry and laser scanning cytometry, a comparison of techniques. J Clin Monit Comput. 2010;24:251–259. doi: 10.1007/s10877-010-9242-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield CD, Man A, Shaw RA. Integration of microfluidics with biomedical infrared spectroscopy for analytical and diagnostic metabolic profiling. IEE Proc Nanobiotechnol. 2006;153:74–80. doi: 10.1049/ip-nbt:20050028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Lin SC, Dong C, Huang TJ. Single-layer planar on-chip flow cytometer using microfluidic drifting based three-dimensional (3D) hydrodynamic focusing. Lab Chip. 2009;9:1583–1589. doi: 10.1039/b820138b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauk MG, Ziober BL, Chen Z, Thompson JA, Bau HH. Lab-on-a-chip technologies for oral-based cancer screening and diagnostics: capabilities, issues, and prospects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1098:467–475. doi: 10.1196/annals.1384.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr LM, Bojanic D. Novel trends in high-throughput screening. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed MR. A brief history of flow cytometry and sorting. Methods Cell Biol. 2001;63:3–17. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(01)63005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen U. Microfluidics in medical applications. Med Device Technol. 2007;18:12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers FB, Lee LP. Innovations in optical microfluidic technologies for point-of-care diagnostics. Lab Chip. 2008;8:2015–2031. doi: 10.1039/b812343h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakey J, Applegate RW, Jr, Arellano E, Di Carlo D, Graves SW, Toner M. Particle focusing in staged inertial microfluidic devices for flow cytometry. Anal Chem. 2010;82:3862–3867. doi: 10.1021/ac100387b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong PK, Lim D, Kim S. Are microfluidics-based blood viscometers ready for point-of-care applications? A review Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2010;38:189–200. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v38.i2.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkova Z, Vachova L, Valer M, Preckel T. Single-cell analysis of yeast, mammalian cells, and fungal spores with a microfluidic pressure-driven chip-based system. Cytometry A. 2004;59:246–253. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl T, Mugele F, Seemann R, Herminghaus S. Trends in microfluidics with complex fluids. Chemphyschem. 2003;4:1291–1298. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200300847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polson NA, Hayes MA. Microfluidics: controlling fluids in small places. Anal Chem. 2001;73:312A–319A. doi: 10.1021/ac0124585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugmire DL, Waddell EA, Haasch R, Tarlov MJ, Locascio LE. Surface characterization of laser-ablated polymers used for microfluidics. Anal Chem. 2002;74:871–878. doi: 10.1021/ac011026r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi S, Liu X, Ford S, Barrows J, Thomas G, Kelly K, McCandless A, Lian K, Goettert J, Soper SA. Microfluidic devices fabricated in poly(methyl methacrylate) using hot-embossing with integrated sampling capillary and fiber optics for fluorescence detection. Lab Chip. 2002;2:88–95. doi: 10.1039/b200370h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig JR, Folch A. Large-scale single-cell trapping and imaging using microwell arrays. Anal Chem. 2005;77:5628–5634. doi: 10.1021/ac0505977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revzin A, Sekine K, Sin A, Tompkins RG, Toner M. Development of a microfabricated cytometry platform for characterization and sorting of individual leukocytes. Lab Chip. 2005;5:30–37. doi: 10.1039/b405557h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaff UY, Xing MM, Lin KK, Pan N, Jeon NL, Simon SI. Vascular mimetics based on microfluidics for imaging the leukocyte–endothelial inflammatory response. Lab Chip. 2007;7:448–456. doi: 10.1039/b617915k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R, Sethu P, Harnett CK. Three-dimensional hydrodynamic focusing in a microfluidic Coulter counter. Rev Sci Instrum. 2008;79:046104. doi: 10.1063/1.2900010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro HM. The evolution of cytometers. Cytometry A. 2004;58:13–20. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia SK, Kricka LJ. Microfluidics and point-of-care testing. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1982–1983. doi: 10.1039/b817915h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia SK, Whitesides GM. Microfluidic devices fabricated in poly(dimethylsiloxane) for biological studies. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:3563–3576. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims CE, Allbritton NL. Analysis of single mammalian cells on-chip. Lab Chip. 2007;7:423–440. doi: 10.1039/b615235j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Situma C, Hashimoto M, Soper SA. Merging microfluidics with microarray-based bioassays. Biomol Eng. 2006;23:213–231. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skommer J, Darzynkiewicz Z, Wlodkowic D. Cell death goes LIVE: technological advances in real-time tracking of cell death. Cell Cycle. 2010;9 doi: 10.4161/cc.9.12.11911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroock AD, Fischbach C. Microfluidic culture models of tumor angiogenesis. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2143–2146. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svahn HA, van den Berg A. Single cells or large populations? Lab Chip. 2007;7:544–546. doi: 10.1039/b704632b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S, Ostuni E, LeDuc P, Naruse K, Ingber DE, Whitesides GM. Subcellular positioning of small molecules. Nature. 2001;411:1016. doi: 10.1038/35082637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S, Ostuni E, LeDuc P, Naruse K, Ingber DE, Whitesides GM. Selective chemical treatment of cellular microdomains using multiple laminar streams. Chem Biol. 2003;10:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Jimma F. Maintenance free biosafety flowcytometer using disposable microfluidic chip (FISHMAN-R) Cytometry B. 2009;76B:405–406. [Google Scholar]

- Takao M, Jimma F, Takeda K. Expanded applications of new-designed microfluidic flow cytometer (FISHMAN-R) Cytometry B. 2009;76B:405. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas RS, Morgan H, Green NG. Negative DEP traps for single cell immobilisation. Lab Chip. 2009;9:1534–1540. doi: 10.1039/b819267g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ren L, Li L, Liu W, Zhou J, Yu W, Tong D, Chen S. Microfluidics: a new cosset for neurobiology. Lab Chip. 2009;9:644–652. doi: 10.1039/b813495b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MM, Tu E, Raymond DE, Yang JM, Zhang H, Hagen N, Dees B, Mercer EM, Forster AH, Kariv I, Marchand PJ, Butler WF. Microfluidic sorting of mammalian cells by optical force switching. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:83–87. doi: 10.1038/nbt1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Kim MC, Marquez M, Thorsen T. High-density microfluidic arrays for cell cytotoxicity analysis. Lab Chip. 2007;7:740–745. doi: 10.1039/b618734j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrick JW, Murphy WL, Beebe DJ. Screening the cellular microenvironment: a role for microfluidics. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2008;1:75–93. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2008.2008241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel DB, Whitesides GM. Applications of microfluidics in chemical biology. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigl B, Domingo G, Labarre P, Gerlach J. Towards non- and minimally instrumented, microfluidics-based diagnostic devices. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1999–2014. doi: 10.1039/b811314a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DB, Carpenter AE, Sabatini DM. Cell microarrays and RNA interference chip away at gene function. Nat Genet. 2005;37(Suppl):S25–30. doi: 10.1038/ng1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesides GM. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature. 2006;442:368–373. doi: 10.1038/nature05058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodkowic D, Cooper JM. Microfabricated analytical systems for integrated cancer cytomics. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010a;398:193–209. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3722-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodkowic D, Cooper JM. Microfluidic cell arrays in tumor analysis: new prospects for integrated cytomics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2010b;10:521–530. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodkowic D, Cooper JM. Tumors on chips: oncology meets microfluidics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010c;14:556–567. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodkowic D, Faley S, Skommer J, McGuinness D, Cooper JM. Biological implications of polymeric microdevices for live cell assays. Anal Chem. 2009a;81:9828–9833. doi: 10.1021/ac902010s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodkowic D, Faley S, Zagnoni M, Wikswo JP, Cooper JM. Microfluidic single-cell array cytometry for the analysis of tumor apoptosis. Anal Chem. 2009b;81:5517–5523. doi: 10.1021/ac9008463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodkowic D, Skommer J, Darzynkiewicz Z. Cytometry in cell necrobiology revisited. Recent advances and new vistas. Cytometry A. 2010;77:591–606. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodkowic D, Skommer J, Faley S, Darzynkiewicz Z, Cooper JM. Dynamic analysis of apoptosis using cyanine SYTO probes: from classical to microfluidic cytometry. Exp Cell Res. 2009c;315:1706–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodkowic D, Skommer J, McGuinness D, Faley S, Kolch W, Darzynkiewicz Z, Cooper JM. Chip-based dynamic real-time quantification of drug-induced cytotoxicity in human tumor cells. Anal Chem. 2009d;81:6952–6959. doi: 10.1021/ac9010217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff A, Perch-Nielsen IR, Larsen UD, Friis P, Goranovic G, Poulsen CR, Kutter JP, Telleman P. Integrating advanced functionality in a microfabricated high-throughput fluorescent-activated cell sorter. Lab Chip. 2003;3:22–27. doi: 10.1039/b209333b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood DK, Weingeist DM, Bhatia SN, Engelward BP. Single cell trapping and DNA damage analysis using microwell arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10008–10013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004056107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarmush ML, King KR. Living-cell microarrays. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2009;11:235–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.10.061807.160502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaouk R, Park BY, Madou MJ. Fabrication of polydimethylsiloxane microfluidics using SU-8 molds. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;321:17–21. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-997-4:17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Lin S, Wang C, Hu J, Li C, Zhuang Z, Zhou Y, Mathies RA, Yang CJ. PMMA/PDMS valves and pumps for disposable microfluidics. Lab Chip. 2009;9:3088–3094. doi: 10.1039/b907254c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T, Luo C, Huang J, Xiong C, Ouyang Q, Fang J. Electroporation based on hydrodynamic focusing of microfluidics with low dc voltage. Biomed Microdevices. 2010;12:35–40. doi: 10.1007/s10544-009-9355-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]