Abstract

Using non-conventional markers, DNA metabarcoding allows biodiversity assessment from complex substrates. In this article, we present ecoPrimers, a software for identifying new barcode markers and their associated PCR primers. ecoPrimers scans whole genomes to find such markers without a priori knowledge. ecoPrimers optimizes two quality indices measuring taxonomical range and discrimination to select the most efficient markers from a set of reference sequences, according to specific experimental constraints such as marker length or specifically targeted taxa. The key step of the algorithm is the identification of conserved regions among reference sequences for anchoring primers. We propose an efficient algorithm based on data mining, that allows the analysis of huge sets of sequences. We evaluate the efficiency of ecoPrimers by running it on three different sequence sets: mitochondrial, chloroplast and bacterial genomes. Identified barcode markers correspond either to barcode regions already in use for plants or animals, or to new potential barcodes. Results from empirical experiments carried out on a promising new barcode for analyzing vertebrate diversity fully agree with expectations based on bioinformatics analysis. These tests demonstrate the efficiency of ecoPrimers for inferring new barcodes fitting with diverse experimental contexts. ecoPrimers is available as an open source project at: http://www.grenoble.prabi.fr/trac/ecoPrimers.

INTRODUCTION

DNA barcoding opens new opportunities for biodiversity research. This technique is now considered to be a powerful tool, both for taxonomical (1) and ecological (2) studies. Taxonomies based solely on morphological analyses are sometimes problematic due to either convergence in phenotypes among distantly related species, or the failure to identify cryptic species where morphologic divergence has not kept pace with genetic divergence (3). Though the original aim of DNA barcoding was to assign an unambiguous molecular identifier to each taxon (1), today new DNA barcoding applications are emerging. These applications apply DNA barcodes not as a means to unambiguously identify a single specimen from a taxonomical point of view, but as a tool for better characterizing a set of taxa from a complex biological sample. This metabarcoding approach (i.e. the simultaneous identification of many taxa from the same sample) has a wide range of applications in forensics, ecology and palaeoecology.

Following the original (sensu stricto) barcode definition, a barcode marker must be as universal as possible and must contain enough information to discriminate between closely related species and to discover new ones. The Consortium for the Barcode of Life (CBoL: http://www.barcodeoflife.org) leads the standardization of such markers. For example, the COI gene is recommended for animal barcoding (1). However, in ecological research, other constraints must sometimes be considered when selecting a barcode marker and its associated primers. As a consequence, the standardized COI animal barcode that clearly fulfills all the requirements for specimen identification (1) is not always the most efficient one for a metabarcoding approach.

Metabarcoding constraints on the locus choice

Sensu stricto barcode applications prefer long barcode markers with high discrimination capacity and, if possible, high phylogenetic information content. For these reasons the COI gene for animals (1) and rbcL and matK genes for plants (4) are recommended by CBoL. Metabarcoding has a different aim and requires different optimality criteria for the markers employed: (i) as the DNA will often be degraded (and to minimize the risk of chimeric sequences) shorter amplicons are needed, and (ii) to minimize amplification biases in mixed-template reactions, the primers need to be highly conserved. Furthermore, taxonomic resolution at the species level is not always required. Identification at a higher taxonomic level (e.g. family, order, etc.) is sometimes sufficient. Thus in some conditions, it might be necessary to select a short marker even if its resolution is low.

Metabarcoding constraints on the primer choice

Sensu stricto barcode applications usually rely on PCR amplifications from good quality DNA extracted from a single specimen. This allows the use of degenerate primers and relaxed PCR conditions, with the key constraint of amplifying the same highly informative standard locus from the broadest range of organisms. A contrario, metabarcode applications require robust PCR conditions allowing unbiased amplifications from a mix of several DNA templates which are often degraded [DNA extracted from modern and ancient soils (5,6), water (7) or animal feces (8,9)]. This imposes the use of highly conserved primers for simplifying PCR amplification conditions and reducing disequilibrium in amplification among the different DNA templates. Moreover, it can be advantageous to select primers amplifying only a subset of taxa for solving a given biological question (i.e. excluding the amplification of other taxonomic groups).

Tracking the ideal barcode markers

Ideal metabarcode markers should be short, highly discriminant, restricted to the studied clades and have highly conserved primer sites. Such ideal markers might not be the same among studies. In many cases this requires a specific pair of primers be designed to exactly fit the biological question.

The traditional method for identifying barcode regions is human observation of sequence alignments to locate two conserved regions flanking a variable one. This manual approach obliges barcode designers to work on well-known sets of genes. Based on this approach, several manually discovered barcode loci are in routine use today, including regions of protein encoding genes such as COI (1,12), rbcL or matK (4), RNA genes like mitochondrial 12S (13) or 16S (14) rDNA and non-coding chloroplast regions such as the trnL intron (15) or the intergenic trnH-psbA region (16). Several tools exist to help biologists during the primer design step, but they were not often developed for the context of DNA barcoding. Among them, Primer3 (17) and QPrimer (18) use a single training sequence and were clearly not developed for designing versatile primers. TmPrime (19) and UniPrimer (20) can work on a training set of short sequences (i.e. gene sequences), allowing the design of primers that amplify several homologous sequences. But these tools are not adapted for long sequences (i.e. whole genomes) and do not take into account the taxonomic discrimination capacity of the amplified sequence during the primer selection process. More interestingly, PrimerHunter (21) was developed to select highly specific primers for distinguishing virus subtypes, a typical sensu lato barcoding application. Unfortunately, its efficiency on large data sets of long sequences is problematic. We were unable to run it on a 13.7 MB (Megabyte) database corresponding to the full set of whole mitochondrial genomes extracted from GenBank. Finally, Amplicon (22) allows for selecting specific primers to a group of aligned sequences and excluding a counterexample data set. But, as Amplicon requires aligned sequences, it can only design primers from a set of short regions compatible with multi-alignment software capacity and so cannot be run with a whole-genome data set.

To efficiently infer new metabarcode markers, we developed a software, ecoPrimers, fulfilling the following prerequisites: (i) the ability to scan a large database of whole genomes allowing the selection of markers without a priori identification, (ii) the ability to select highly conserved primers among a training set of sequences (example sequences) and possibly not amplifying a counterexample set of sequences (iii) the ability to test an amplified region for its capacity to discriminate among taxa. For achieving these goals, we took advantage of two indices previously proposed to evaluate in silico the relative quality of barcode primers in the context of metabarcoding (10). The first index, Bc, estimates the coverage or taxonomical amplification range of a primer pair. The second, Bs, evaluates the taxonomical discrimination capacity of the amplified marker among the amplified taxa. These indices have been successfully used by Bellemain et al. (11) to demonstrate the importance of primer selection for metabarcoding studies of fungal communities. ecoPrimers selects primer pairs by optimizing these two indices. A special effort was made to ensure computational efficiency of the program, and this was tested on the one thousand bacterial genomes currently available in public databases.

Here we used ecoPrimers to design specific primer pairs for bacterial, chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes. Validation by empirical experiments of the primer pairs selected to identify the vertebrates confirms that ecoPrimers proposed specific and robust primer pairs for amplifying target sequences. ecoPrimers is available as an open source software at: http://www.grenoble.prabi.fr/trac/ecoPrimers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Problem formulation

We assume that all sequences are texts over the DNA alphabet {A, C, G, T}, and that the orientation of sequences is unknown. Given a set of example sequences Es and an optional second set of counterexample sequences Cs, we want to identify highly conserved primers which are present in the largest possible subset of Es and in the smallest subset of Cs. Highly conserved primers are defined as words of length lp, (i) strictly present in at least Qs sequences of Es, (ii) present in at least Qe sequences of Es with no more than e mismatches (optionally we can impose that these errors are not located in the n last 3′ bases of the primers to be more realistic in subsequent empirical DNA amplification), (iii) not present in more than Qx sequences of Cs. The same approximative matching conditions used for Qe are applied to this quorum. By default Qs is set to 70% of |Es|, Qe is set to 90% of |Es| and Qx is set to 10% of |Cs|. Identified potential primers are then paired with respect to their locations and orientation to allow amplification of those DNA fragments that are within the size range specified by the user.

Algorithm

In a nutshell, our method consists of five steps: (i) finding strict primers (i.e. without mismatch) from Es respecting Qs; (ii) using these strict primers as models to find their non-strict occurrences (i.e. with mismatches) in Es to check Qe and in Cs to check Qx; (iii) building the primer pairs, (iv) evaluating Bc and Bs indices to select the best primers, and (v) estimating the melting temperature of each of the primers in selected pairs.

Finding strict repeats

Finding conserved regions among a set of sequences is an equivalent problem to finding repeats among those sequences. Identification of repeats in DNA sequences is a well-known problem in bioinformatics and many efficient data structures and associated algorithms exist for finding strict repeats, such as KMR (23), suffix tree (24) and suffix array (25). These algorithms work well on short sequences but are not efficient enough for us in terms of memory usage for finding repeats in a quorum of a large number of very long sequences (i.e. the set of all whole sequenced bacterial genomes available in public databases, approximatively 1000 genomes and 3 Gb (gigabases) of sequences). The best implementation of suffix tree was developed in Reputer (26). It uses about 12.5 bytes per nucleotide to build the data structure. This compact implementation is based on a 32 bit architecture; consequently it cannot manipulate sequence data larger than 340 Mb (megabases). Similarly, the most compact implementation of KMR is done in RepSeek, (27) which uses about 9 bytes per nucleotide on a 32 bit architecture, corresponding to a limit of 475 Mb. The last structure, suffix array, requires 4 bytes per nucleotide on a 32 bit, and 4 more bytes to be efficiently used to infer repeats. These two values have to be multiplied by 2 on a 64 bit architecture. Finally, as we do not assume that all the sequences are in the same orientation, we have to encode the direct and the reverse strand in the data, multiplying by two the memory requirement.

These three algorithms simultaneously identify conserved motifs and the positions of their occurrences. Following our brief description of the ecoPrimers algorithm, we just need the motif and the number of the sequences in which they occur. We do not need their exact positions, as they will be recomputed in step (ii) taking into account mismatches. We take advantage of this to gain memory compactness.

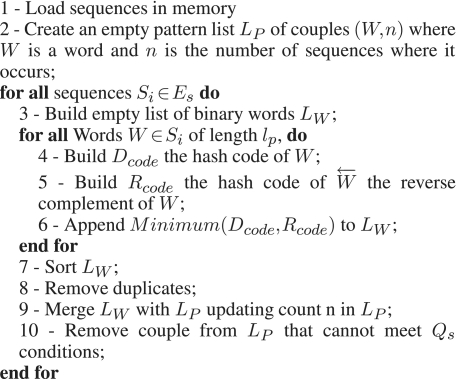

For ecoPrimers we have developed a simple algorithm for finding strict repeats which is notably compact in memory. This algorithm is based on a sort and a merge algorithm and some data mining steps. The algorithm presented in Figure 1 (named Strict Primer Algorithm, SPA) gives the outline of our strict repeats finding procedure without a data mining step.

Figure 1.

Strict primer algorithm (SPA) used for finding strict repeats.

In the first step, we load all sequences in memory. Then we construct an empty list LP that will contain the strict repeats found at the end of the algorithm as a set of couple (W, n) where W is a word and n is the number of sequences where it occurs. In the third step, for each input sequence Si of Es, we build LW, the list of all overlapping words of length lp. For purpose of compactness, words are saved as a 64-bit binary hash code (named further Dcode or Rcode) following the encoding schema {A = 00, C = 01, G = 10, T = 11}. This allows us to manipulate words up to 32 nucleotides long.

To look for repeats in both strands of a DNA sequence, standard algorithms are required to store direct and reverse sequences in their data structures. In a double stranded DNA sequence, occurrence position is defined by a position and an orientation. As in our algorithm, occurrence positions are not important at this stage, orientations of enumerated words do not have to be stored. Thus, if a word W occurs n times in both strands of a sequence,  the reverse complement corresponding word of W also occurs n times. Therefore we just need to count one of the two (W or

the reverse complement corresponding word of W also occurs n times. Therefore we just need to count one of the two (W or  ). The actual counted word for a given word pair

). The actual counted word for a given word pair  is the one corresponding to the smaller hash code between Dcode and Rcode.

is the one corresponding to the smaller hash code between Dcode and Rcode.

Sorting (Step 7) is achieved using the Smoothsort algorithm (25,28). This algorithm has a complexity of O(nlogn) in the worst case, as do several other sorting algorithms, but has a complexity near to O(n) when the input array is almost ordered.

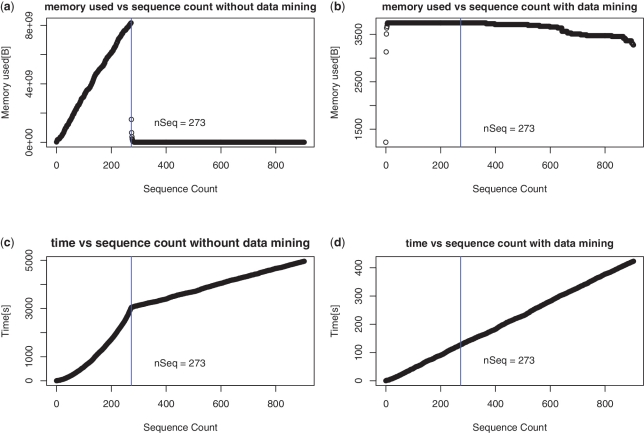

The merge (Step 9) of the two lists LP and LW is achieved in place and in a linear time using just an extra buffer of size = minimum(|LP|, |LW|). During this merging step words that will not be able to respect Qs are eliminated of LP. Despite this, the |LP| increases quickly until |Es| − Qs sequences are analyzed (Figure 2a). This technique is sufficient for data sets of reasonable size, but for large data sets like fully sequenced bacterial genomes having total size of approximately 3 Gb, it consumes a significant amount of memory. To overcome this problem a pre-filtration/data-mining step was added.

Figure 2.

Comparison of time and memory usages of the both versions of the SPA. (a) Memory used with respect to the sequences processed without data mining step. Memory used increases rapidly until strict quorum (70%) starts taking effect after 271 (30% of 905) sequences have been processed (b) Same but with data mining step. Only a small number of prefix of 13 bases for primers of length18 bases pass the strict quorum, hence memory used is significantly small. (c) Time required to process the sequences without data mining increases exponentially until strict quorum starts making effect and after that time becomes linear. (d) With the data mining step added, time required becomes linear.

Data mining

Data mining used for finding strict repeats is based on the fact that all words W of size lp present in at least Qs sequences of Es are composed only of words Wm of size lm ≤ lp present in at least Qs sequences of Es. Using the binary encoding schema presented previously, we built a complete hash table Hm of all words Wm of size lm = 13. Each cell of this table stores the count of sequences where the corresponding word occurs. As we have 413 = 67 108 864 different words of size lm, and for each word the hash table used 4 bytes, 256 MB of memory is required to store it. This size is small if we compare it to the 3 GB used to store the bacterial genome sequences and more than 8 GB used by SPA to store the LP list corresponding to these sequences. Hm is built in a linear time.

To include data mining in SPA, we just added a condition on Hm in the building hash code methods of Steps 3 and 4 (Figure 1), verifying the assertion that no word Wm ∈ W is present in less than Qs sequences. As computation of the next hash code at Steps 3 and 4 is achieved by bit shifting of the previous one, only one lookup into Hm is required per hash code generated. Each lookup is done in constant time so data mining does not change the global complexity of the initial algorithm.

Finding approximate primers

In the above step we have found a list of words LP which are present in at least Qs of the Es. In this step, we find the approximate occurrences of these words in all the example sequences Se ∈ Es and all the counterexample sequences Sc ∈ Cs. For this purpose, we use these strict words as patterns and find their approximate occurrences using the agrep algorithm (29). At the end, we conserve only words occurring in more than Qe sequences of Es with no more than e errors (i.e. mismatches). From these words, the words which are not present in more than Qx sequences of Cs are tagged as good primers.

Pairing the primers

Words must finally be paired to delimit potential barcode regions. Pairing is done for all the sequences with an almost linear time algorithm checking the minimal (lmin) and maximal length (lmax) constraint imposed on the potentially amplified sequence. Each pair must contain at least one good primer (specificity of a single primer is enough to ensure specificity of the amplified region). A primer pairs is composed of two words and their relative orientation indicates which one of W and  must be used as primer. Once orientation is defined only pairs satisfying the constraint of no mismatches on the n last 3′ bases of the primer are conserved.

must be used as primer. Once orientation is defined only pairs satisfying the constraint of no mismatches on the n last 3′ bases of the primer are conserved.

Applying the quality indices

Once constructed, the primer pairs can be evaluated using both the indices Bc and Bs defined in Ficetola et al. (10). Bc the barcode coverage index is the ratio between the number of amplified taxa and |Es|. Bs the barcode selectivity index is the ratio between the number of identified taxa and |Es|. These indices can be efficiently computed in ecoPrimers using data stored during the pairing process.

Melting temperature calculation

ecoPrimers uses the nearest neighbor thermodynamic model (30) for melting temperature (Tm) computation. Using this technique we estimate Tm of the perfect match of the primer and of the worst match of the primer on the example sequence. The temperatures are calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

Here, ΔH and ΔS are enthalpy and entropy changes for annealing reaction respectively. This annealing reaction results in a duplex having Watson–Crick base pairs. N is the total number of phosphates in the duplex, R is the universal gas constant, C is the total DNA concentration from (30) and Na+ is the concentration of salt cations. ΔH and ΔS are computed by summing experimentally estimated contributions of constituting dimer duplexes as in (21).

Empirical ecoPrimers evaluation

ecoPrimers must be evaluated for its computational efficiency and the quality of its results. Efficiency was tested using the large eubact data set (vide infra). The quality of the results proposed by ecoPrimers can be checked by comparing proposed barcodes with ones currently used. If we assume that previously used barcodes were designed empirically but correctly, we hope that a subset of ecoPrimers results must correspond to them. For this purpose three different training data sets and their associated parameters were used.

The eubact data set contains 905 whole eubacteria genomes extracted from Genome Review release 115 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/GenomeReviews) (31). They correspond to 603 species belonging to 311 genera. Their median size is 3.5 Mb. To identify barcodes similar to those used in bacterial biodiversity studies of soil (33), ecoPrimers was run on this data set using default parameters and searching for a marker of size smaller than 1 Kb (kilobases). The e parameter was set to 3.

The chloro data set contains 175 whole chloroplast genomes extracted from Genbank using eutils web api (http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) in January 2010. They correspond to 174 species belonging to 145 genera. From these sequences 119 belong to Tracheophyta (vascular plants, NCBI Taxid: 58023) corresponding to 118 species in 93 genera. The median size of the 175 sequences is 152 Kb. In order to find markers useful for environmental studies on vascular plant biodiversity (15), ecoPrimers was run on this data set with the default parameters, searching for markers with a size ranging from 10 bp to 120 bp. The e parameter was set to 3. The search was taxonomically restricted to Tracheophyta.

The mito data set is composed of 2044 whole mitochondrion genomes extracted from Genbank using eutils web api. They correspond to 2002 species belonging to 1549 genera. Among these sequences 1293 belong to Vertebrata (NCBI Taxid: 7742) corresponding to 1261 species in 966 genera. The median size of the 2044 sequences is 16.6 Kb. To search for markers usable in diet analysis studies of Carnivora, ecoPrimers was run on this data set with the default parameters, looking for markers with a size ranging from 50 bp to 120 bp. The e parameter was set to 3. On this data set two taxonomical restrictions were used. The first restricts the example sequence set ES to NCBI Taxid: 7742 (Vertebrata) to optimize primers for vertebrates. The second defines the CS counterexample sequence set to NCBI Taxid: 1 (Root) requiring that primers not match on sequences belonging to non-vertebrates.

In silico primer checking

Primers were checked against full Nucleic EMBL Standard release 103 database using the electronic PCR software ecoPCR (10). The resulting ecoPCR output file contains all data about potentially amplified sequences, among them the size of the amplicon, the number of mismatches associated to each primer and the taxa associated with the amplified sequences.

Empirical primer testing

Empirical testing was done for only one primer pair, named 12S-V5. This primer pair was designed by ecoPrimers when run on the mito data set with the above mentioned parameters. This primer pair had reasonably high values of Bc and Bs indices with relatively short amplification length as shown in Table 3, making it suitable for amplification from degraded DNA. 12S-V5 primer pair was empirically tested in diet analysis of three felid species, namely snow leopard (Uncia uncia), common leopard (Panthera pardus) and leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) using feces as a source of DNA. The feces sampling was done by field workers of The Snow Leopard Trust (http://www.snowleopard.org). Snow leopard feces were collected from Mongolia in 2009 while common leopard and leopard cat feces were collected from Pakistan in 2008.

Table 3.

The five best primer pairs proposed by ecoPrimers to amplify potential barcode markers specific of vertebrates

| Primer Name | Sequences |

Tm |

Amplified |

Bc | Bs | Fragment size (bp) |

Region | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Reverse | P1 | P2 | Es | Cs | Min | Max | Average | ||||

| ACTGGGATTAGATACCCC | TAGAACAGGCTCCTCTAG | 52.6 | 52.3 | 1221 | 31 | 0.968 | 0.858 | 85 | 117 | 105.38 | 16S RNA | |

| 12S–V5 | TAGAACAGGCTCCTCTAG | TTAGATACCCCACTATGC | 52.3 | 50.7 | 1236 | 7 | 0.980 | 0.720 | 73 | 110 | 98.32 | 12S RNA |

| AGGGATAACAGCGCAATC | TCGTTGAACAAACGAACC | 55.6 | 54.4 | 1256 | 18 | 0.996 | 0.459 | 63 | 84 | 82.03 | 12S RNA | |

| similar to 16Sr | CTCCGGTCTGAACTCAGA | GATGTTGGATCAGGACAT | 56.1 | 52.1 | 1253 | 59 | 0.994 | 0.196 | 53 | 59 | 58.22 | 16S RNA |

| ATGTTGGATCAGGACATC | CTCCGGTCTGAACTCAGA | 52.1 | 56.1 | 1253 | 35 | 0.994 | 0.195 | 54 | 60 | 57.22 | 16S RNA | |

DNA extractions were performed from about 15 mg of feces with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAgen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and recovered in a total volume of 250 μl. Amplifications were carried out in a final volume of 25 μl, using 2 μl of DNA extract as template. The amplification mixture contained 1 U AmpliTaq® Gold DNA Polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), 10 mM Tris–HCl, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 0.1 μM of each primer (12SV05F/R), and 5 μg bovine serum albumin (BSA, Roche Diagnostic, Basel, Switzerland). The PCR mixture was denatured at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, and 30 s at 60°C; as the target sequences are shorter than 120 bp, the elongation step was removed to reduce the +A artifact (34,35) that might decrease the efficiency of the first step of the sequencing process (blunt-end ligation). The sequencing was carried out on an Illumina/Solexa Genome Analyzer IIx (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA 92121, USA), using the Paired-End Cluster Generation Kit V4 and the Sequencing Kit V4 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA 92121, USA), and following manufacturer's instructions. A total of 108 nucleotides were sequenced on each extremity of the DNA fragments.

The sequence reads were analyzed using the OBITools software (http://www.prabi.grenoble.fr/trac/OBITools). First, the direct and reverse reads corresponding to a single molecule were aligned and merged using the solexaPairEnd program, taking into account data quality during the alignment and the consensus computation. Then, primers and DNA tag identifying samples were identified using the ngsfilter program. The amplified regions, excluding primers, were kept for further analysis. Strictly identical sequences were clustered together using the obiuniq program. Sequences shorter than 10 bp, or containing degenerated IUPAC nucleotide codes (other than A, C, G and T), or with occurrence less than or equal to 10 were excluded using the obigrep program. Taxon assignment was achieved using the ecoTag program (9). EcoTag relies on a dynamic programming global alignment algorithm (32) to find highly similar sequences in the reference database. This database was built by extracting the region between the two primers 12S-V5 of the mitochondrial 12S gene from EMBL nucleotide library using the output of the ecoPCR program, allowing a maximum of three mismatches between each primer and its target (10).

All computations were done on a LINUX DELL server with 32 GB of RAM (Random Access Memory).

RESULTS

Empirical testing of ecoPrimers on a large data set

The ability of ecoPrimers to analyze full genome data sets, allowing it to identify barcodes without a priori targeting of any potential locus, relies on its algorithm efficiency. Efforts have been made during algorithm conception both in terms of memory and time. We have empirically estimated the memory requirements of SPA and compared it with three algorithms KMR (23), Suffix trees (24) and Suffix arrays (25). Memory and time complexities were estimated using eubact as data set. Size of LP list and computation time was measured after each sequence insertion during SPA execution.

SPA without data mining

The program was first run without data mining. Figure 2a displays the evolution of LP size. As expected, it increased during the insertion of the first 273 sequences. The limit value corresponds to |Es| − Qs + 1. At this point, many words could not reach Qs and were discarded from LP. The maximum size of LP is about 7.8 GB for 3 Gb of sequences. This corresponds to a usage of about 3.6 bytes per nucleotide analyzed on both strands, including one byte to store the sequence itself. This is already better than the three standard algorithms, but this transient long list has a drastic impact on memory and speed performances. Time evolution during execution (Figure 2c) evolves in a quadratic way with the sequence count. Theoretically, in the worst case, the algorithm has a complexity of O(N2) during this phase, where N is count of processed sequences. Then time evolves linearly, as |LP| becomes very small. With eubact data set, total time used for the strict primer algorithm is about 1 h and 40 min.

SPA with data mining

The experiment was repeated with data mining activated. This time the majority of hashed words were not included in the LW list because they occurred in less than Qs sequences of Es. The effect of this reduction of |LW| is observable on Figure 2b. The memory size of LP is never over 2.5 KB (less than 210 patterns). The global size used with data mining including Hs, LP, LW and the sequence itself is about 1.1 bytes per nucleotide. The second effect of this drastic size reduction of LP and LW is the speed increase. With data mining the execution time of the strict primer detection is about 5 min (2 min for Hm building and 3 min for strict primer detection). Moreover empirical time complexity is now linear with the count of sequences (Figure 2d).

Global execution

A full search for primers using data mining on the eubact data set is about 3 h 40 min. Main time is devoted to the agrep algorithm. Execution time of this part of our global algorithm is in O((|Es + |Cs|)|LP|). On this data set ecoPrimers never used more than 4 GB of memory.

Designed primers

A Eubacteria training data set was used to demonstrate efficiency of the algorithm, so primers identified with this data set were not checked further. The program proposed almost 5521 primer pairs. Out of these 5521 primer pairs, we investigated the first few pairs and they seem to amplify part of functional RNA genes (rRNA 16S gene, rRNA 23S genes). The five pairs are presented in Table 1, they all correspond to parts of the 16S gene.

Table 1.

The five best primer pairs proposed by ecoPrimers to amplify potential barcode markers specific of eubacteria

| Sequences |

Tm |

Amplified Es | Bc | Bs | Fragment size (bp) |

Region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Reverse | P1 | P2 | Min | Max | Average | ||||

| CGACACGAGCTGACGACA | CTACGGGAGGCAGCAGTG | 60.5 | 60.8 | 603 | 1.00 | 0.927 | 668 | 987 | 699.07 | 16S RNA |

| CTACGGGAGGCAGCAGTG | GGTATCTAATCCTGTTTG | 60.8 | 47.5 | 603 | 1.00 | 0.910 | 392 | 708 | 417.52 | 16S RNA |

| CTACGGGAGGCAGCAGTG | GCGGGCCCCCGTCAATTC | 60.8 | 64.9 | 603 | 1.00 | 0.907 | 525 | 844 | 556.49 | 16S RNA |

| AGCAGCCGCGGTAATACG | GCGGGCCCCCGTCAATTC | 61.1 | 64.9 | 603 | 1.00 | 0.842 | 370 | 666 | 380.21 | 16S RNA |

| ACCGCGGCTGCTGGCACG | CTACGGGAGGCAGCAGTG | 69.6 | 60.8 | 603 | 1.00 | 0.819 | 128 | 598 | 152.66 | 16S RNA |

Amplified Es column indicates electronically amplified species count belonging to the Eubacteria data set.

Validation of ecoPrimers on vascular plants

As the majority of already published barcodes for plants correspond to regions of the chloroplast DNA (4,15,16), we ran ecoPrimers on the chloro data set. Three hundred and forty three primer pairs were selected out of 265 273 primer pairs identified limiting the value of barcode specificity to at least 50%. The specified parameters allow the selection of markers with properties similar to that of g/h primers (15). These primers have already been used for several metabarcoding applications, such as diet analysis (9,36) or to reconstruct past arctic vegetation (6). Table 2 presents the five primers pairs selected from five best regions identified by ecoPrimers. Not only did ecoPrimers identify primers similar to g/h as expected, amplifying the same trnL P6-loop, but it ranked them with the best mark. Most of the primer pairs amplify regions of functional RNA genes, or of introns. (34 primers amplify regions of trnL, 41 primers amplify regions of trnW, 11 primers amplify regions of trnY and 13 primer amplify regions of trnH. Finally 231 primer pairs amplify regions of protein coding genes including psaB, psaA, psbA, psbC and the intergenic region of psbL and psbF).

Table 2.

The five best primer pairs proposed by ecoPrimers to amplify potential barcode markers specific of vascular plants

| Primer name | Sequences |

Tm |

Amplified Es | Bc | Bs | Fragment size (bp) |

Region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Reverse | P1 | P2 | Min | Max | Average | |||||

| similar to g/h | GGCAATCCTGAGCCAAAT | TGAGTCTCTGCACCTATC | 56.1 | 53.5 | 114 | 0.966 | 0.711 | 10 | 90 | 45.65 | trnL-P6-loop |

| similar to g/h | ATTGAGTCTCTGCACCTA | GGGCAATCCTGAGCCAAA | 52.7 | 58.4 | 114 | 0.966 | 0.658 | 13 | 93 | 48.65 | trnL-P6-loop |

| similar to g/h | AGCTTCCATTGAGTCTCT | GGGCAATCCTGAGCCAAA | 53.0 | 58.4 | 111 | 0.941 | 0.649 | 20 | 100 | 55.96 | trnL-P6-loop |

| TGGTTATTTACTAAAATC | TTTGGTTAAGATATGCCA | 41.9 | 48.9 | 116 | 0.983 | 0.647 | 100 | 103 | 100.3 | psbCL | |

| GCAATCCTGAGCCAAATC | GCTTCCATTGAGTCTCTG | 54.8 | 53.4 | 112 | 0.949 | 0.652 | 17 | 97 | 52.73 | trnL | |

g/h primers were proposed by Taberlet et al. (15) for vascular plant identification. Amplified Es column indicates electronically amplified species count belonging to the vascular plant example set.

Validation of ecoPrimers on vertebrates

In a similar way as we did for vascular plants, we ran ecoPrimers on the mito data set, asking for primers amplifying only Vertebrata.

Designed primers

Forty-two primer pairs were identified. As for previous tests, they were mainly located on non-protein coding sequences (30 in rRNA 16S gene, 12 in rRNA 12S gene). The five best primer pairs are presented in Table 3. The first of them, named 12S-V5, was more carefully checked using bioinformatics and experimental approaches (see below). The third and fourth correspond to variants of primers amplifying a region of the 16S rRNA gene already proposed as barcode marker for mammals (14,37)

Bioinformatics validation of the 12S-V5 primer pair

The 12S-V5 primer pair amplifies a part of the 12S rRNA gene including its V5 variable region. The amplified region from the ecoPrimers results range from 73 bp to 110 bp. It is able to amplify 98% of the sequence training set (Bc = 0.98) and unambiguously identifies 74% of those amplified species (Bs = 0.74). Only 7 taxa of over 741 represented in the counterexample set of sequences CS are recognized by this primer pair. Better estimation of the quality of this barcode was achieved using ecoPCR against EMBL nucleotide database (10). We set ecoPCR parameters to allow in silico PCR amplification ranging from a size between 50 bp to 250 bp with no more than 3 mismatches per primer. It resulted in the potential amplification of 17737 sequences of vertebrate (according to the EMBL annotation) and only 79 sequences belonging to other taxa. Of these non-vertebrate sequences, 66 of them belong to the Crustacea (NCBI Taxid: 6657), 5 belong to Insecta (NCBI Taxid: 50557), 3 belong to Arthropoda (NCBI Taxid: 6656) and 1 sequence belongs to each of the following taxa: Gastropoda (NCBI Taxid: 6448), Lineidae (NCBI Taxid: 6222), Loxosomatidae (NCBI Taxid: 231594). All these non-vertebrate taxa present two or three mismatches with both primers. The two last non-vertebrate sequences exhibit zero or one mismatch for both primers but they correspond to mis-assigned taxa. The first one embl:EU626452, annotated as an uncultured bacterium (NCBI Taxid: 77133), is identical to a human sequence. The second one embl:AF257243, annotated as a nematode (Onchocerca volvulus NCBI Taxid: 6282), is similar to many bony fish (Actinopterygii NCBI Taxid: 7898) sequences. The amplified vertebrate sequences correspond to 5926 species and 2732 genera. Among them 4537 species (Bs = 0.77) and 2430 genera (Bs = 0.89) are unambiguously identified. Among the 17737 sequences of vertebrate only 353 have two or three mismatches with the both primers. A total of 266 of them belong to reptiles (Sauropsida NCBI Taxid: 8457), 24 sequences belong to amphibians (Amphibia NCBI Taxid: 8292) and 3 sequences belong to the Batrachoididae family (NCBI Taxid: 8065). The 60 remaining sequences belong to mammals (NCBI Taxid: 40674) but most of these sequences are annotated as a nuclear copy of this mitochondrial locus. Table 4 resumes the distribution of mismatches of the two 12S-V5 primers among vertebrate species.

Table 4.

Number of vertebrate species exhibiting from 0 to 3 mismatches for forward and reverse 12S-V5 primers

| Number of mismatches | Number of species |

|

|---|---|---|

| Forward primer | Reverse primer | |

| 0 | 3272 | 4592 |

| 1 | 2031 | 1021 |

| 2 | 465 | 291 |

| 3 | 158 | 20 |

Experimental validation of primer 12S-V5

The empirical testing of the 12S-V5 primer pair was carried on felid feces, to assess their diet. One, one and two feces were used for snow leopard (U. uncia), common leopard (P. pardus) and leopard cat (P. bengalensis), respectively. The results are summarized in Table 5. As expected, both felid (i.e. predator) and the prey sequences were obtained. The Bs of the amplified sequences allowed us to unambiguously distinguish the three predators, and to identify different prey, including three mammals, one bird and one amphibian.

Table 5.

Count of sequences observed per sample after Solexa sequencing of 4 PCR amplicons

| Feces |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common leopard | Snow leopard | Leopard cat |

|||

| 1 | 2 | ||||

| Predator | Common leopard (P. pardus) | 2460 | – | – | – |

| Snow leopard (U. uncia) | – | 10 807 | - | - | |

| Leopard cat (P. bengalensis) | – | – | 1982 | 9765 | |

| Prey | Domestic goat (Capra hircus) | 2969 | – | – | – |

| Siberian ibex (Capra sibirica) | – | 1256 | – | – | |

| Shrew (Crocidura pullata) | – | – | – | 964 | |

| Chukar partridge (Alectoris chukar) | – | – | 1711 | ||

| Muree hill frog (Paa vicina) | – | – | – | 982 | |

Each of them corresponds to one predator feces.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we have clearly demonstrated the ability of the ecoPrimers software to fulfill all the requirements for designing new barcode regions suitable for metabarcoding studies. This software has the ability to scan large training databases (example and counterexample sets) so as to design highly conserved primers that have the potential to amplify a variable DNA region. The ranking of the primer pairs is based on the two previously proposed indices Bc and Bs (10) that evaluate the taxonomic range potentially amplified by a primer pair, and the discrimination capacity of the amplified region, respectively. A large set of parameters can be specified for tuning the algorithm, including (i) the maximum number of errors allowed between each primer and the target sequence, (ii) the possibility to restrict the search to a given taxonomic level (example set), (iii) the possibility to define a set of counterexample taxa that the primers should not amplify (within or outside of the clade used for the search), (iv) the minimum and maximum length of the amplified region, (v) the possibility to consider that the database sequences are circular, (vi) the possibility to require a strict match on a specified number of nucleotides on 3′-end of the primers, (vii) the proportion of strict matching primers on the example set, (viii) the proportion of primers matching with specified number of errors on the example set, (ix) the proportion of primers matching the counterexample dataset, and finally (x) the possibility of avoiding primers matching more than once in one sequence of the example set. The efficiency of ecoPrimers has been successfully validated, both via bioinformatics analyses and via empirical experiments.

The main advantage and the originality of ecoPrimers is its full integration of the taxonomy. This characteristic has been implemented in a way that allows the design of new barcodes specific to any taxonomic group, as well as the optional exclusion of any other clades. For example, if analyzing the fish diet of an otter (genus Lutra) using their feces, it is possible with ecoPrimers to design a short barcode that includes all teleost fish (Teleostei) and excludes the genus Lutra; such a strategy will not only promote prey DNA amplification, but also prevent otter DNA amplification. Another key advantage is the speed efficiency of the ecoPrimers algorithm when it is used on whole mitochondrial or chloroplast genomes as example sets, and its ability to run on other huge data sets like whole eubacteria genomes.

ecoPrimers is particularly useful for setting up the analysis of environmental samples using a metabarcoding approach. In such a situation, to avoid amplification bias among the different taxonomic groups, it is extremely important to work with highly conserved primers. Unfortunately, for higher taxonomic group (e.g. vertebrate, angiosperms) it is impossible to find primer pairs amplifying all species without mismatch (Bc) and with a good specificity (Bs). So we cannot exclude that some species could be missed by a primer pair. To limit potential problems related to relatively low coverage of a primer pair, it could be useful to analyze the same sample with several markers targeting the same taxonomic group.

The possibility to choose the length of the barcode is crucial when working with degraded DNA: in such a context only fragments shorter than 100 bp can be reliably amplified. According to our experience, in some taxonomic groups, it is even possible to design extremely short barcodes that nevertheless have a very high coverage and specificity. This is the case for earthworms (Lumbricina) where a 30 bp barcode located on the mitochondrial 16S gene allows the identification of all species from the French Alps analyzed up to now (Bienert et al., submitted for publication). Even when using good quality DNA, the length of the sequence reads obtained from the DNA sequencer might impose a maximum length when designing new barcodes. The current standardized barcodes for animals (38) and plants (4) were designed according to the technological characteristics of the sanger sequencing using capillary electrophoresis (sequence reads shorter than 1 kb). In the near future, if the read length of next generation DNA sequencers increases to several kilobases, it might be worthwhile to redesign much longer barcodes to significantly increase the taxonomic resolution. As more and more whole mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes become available, ecoPrimers has the potential to provide new optimal barcodes.

The majority of barcodes proposed by ecoPrimers for Eubacteria, vascular plants and vertebrates are located on ribosomal DNA. The only exception was on chloroplast DNA, with a few primers located either on transfer RNA or on protein genes. As a consequence, the example set of sequences can be taxonomically enlarged by only taking into account the ribosomal genes, and not the whole mitochondrial or chloroplast genomes. In the same way, if the goal is to design a nuclear barcode, the nuclear ribosomal genes can be efficiently used as the example set.

According to our experience, it is sometimes difficult to find suitable short barcodes for some taxonomic groups, particularly if they diverged a very long time ago. Usually, the higher the taxonomic level considered, the greater the difficulty to find universal barcodes. If such a problem occurs, we advise first modifying the parameters by relaxing as much as possible the different constraints, and then trying to design several barcodes, one for each of the taxonomic groups at a lower level. The other option is to degenerate the proposed primers to enlarge their taxonomic coverage. Combined use of ecoPrimers and ecoPCR (10) is convenient for this purpose.

As more and more sequences become available in public databases, by using larger example sets, ecoPrimers will be more and more efficient for designing new barcodes that can be precisely optimized according to the biological question and to the experimental constraints. The biological question might impose a particular level of specificity (e.g. species level), or conversely a broad taxonomic range, but with a resolution at the family level. The experimental constraints might concern the length of the barcode, or the avoidance of amplifying another non-target taxonomic group. The analysis of environmental samples using next generation sequencers is already frequently used for estimating the diversity of bacteria, e.g. (33), fungi, e.g. (39), and more recently of nematodes, e.g. (40). There are more and more research projects extending the approach to other taxonomic groups. In such a context, the availability of a program allowing the design of the most suitable barcode will probably enhance studies analyzing the biodiversity of environmental samples. ecoPrimers is available as an open source software at: http://www.grenoble.prabi.fr/trac/ecoPrimers.

FUNDING

Alocad project (ANR-06-PNRA-004- 02, in part): European Project EcoChange (FP6-036866, in part). The authors T.R. and W.S. were funded by HEC (Higher Education Commission), Government of Pakistan. Funding for open access charge: European Project EcoChange (FP6-036866).

Conflict of interest statement. T.R., P.T. and E.C. are co-inventors of a pending French patent on the primer pair named 12S − V5F and 12S − V5R and on the use of the amplified fragment for identifying vertebrate species from environmental samples. This patent only restricts commercial applications and has no impact on the use of this method by academic researchers.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hebert PDN, Cywinska A, Ball SL, deWaard JR. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2003;270:313–321. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valentini A, Pompanon F, Taberlet P. DNA barcoding for ecologists. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009;24:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahrens D, Monaghan MT, Vogler AP. DNA-based taxonomy for associating adults and larvae in multi-species assemblages of chafers (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 2007;44:436–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. CBOL Plant Working Group (2009) A DNA barcode for land plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 12794–12797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willerslev E, Hansen AJ, Binladen J, Brand TB, Gilbert MTP, Shapiro B, Bunce M, Wiuf C, Gilichinsky DA, Cooper A. Diverse plant and animal genetic records from Holocene and Pleistocene sediments. Science. 2003;300:791–795. doi: 10.1126/science.1084114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sønstebø JH, Gielly L, Brysting AK, Elven R, Edwards M, Haile J, Willerslev E, Coissac E, Rioux D, Sannier J, et al. Using next-generation sequencing for molecular reconstruction of past Arctic vegetation and climate. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010;10:1009–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ficetola GF, Miaud C, Pompanon F, Taberlet P. Species detection using environmental DNA from water samples. Biol Lett. 2008;4:423–425. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valentini A, Miquel C, Nawaz MA, Bellemain E, Coissac E, Pompanon F, Gielly L, Cruaud C, Nascetti G, Wincker P, et al. New perspectives in diet analysis based on DNA barcoding and parallel pyrosequencing: the trnL approach. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009;9:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pegard A, Miquel C, Valentini A, Coissac E, Bouvier F, François D, Taberlet P, Engel E, Pompanon F. Universal DNA-based methods for assessing the diet of grazing livestock and wildlife from feces. J. Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:5700–5706. doi: 10.1021/jf803680c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ficetola GF, Coissac E, Zundel S, Riaz T, Shehzad W, Bessiere J, Taberlet P, Pompanon F. An In silico approach for the evaluation of DNA barcodes. BMC Genom. 2010;11:434. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellemain E, Carlsen T, Brochmann C, Coissac E, Taberlet P, Kauserud H. ITS as an environmental DNA barcode for fungi: an in silico approach reveals potential PCR biases. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meusnier I, Singer GAC, Landry JF, Hickey DA, Hebert PDN, Hajibabaei M. A universal DNA mini-barcode for biodiversity analysis. BMC Genom. 2008;9:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kocher TD, Thomas WK, Meyer A, Edwards SV, Pääbo S, Villablanca FX, Wilson AC. Dynamics of mitochondrial DNA evolution in animals: amplification and sequencing with conserved primers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:6196–6200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palumbi S. Nucleic acids II: the polymerase chain reaction. In: Hillis D, Moritz C, Mable B, editors. Molecular Systematics. 2nd edn. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Assoc.; 1996. pp. 205–247. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taberlet P, Coissac E, Pompanon F, Gielly L, Miquel C, Valentini A, Vermat T, Corthier G, Brochmann C, Willerslev E. Power and limitations of the chloroplast trnL (UAA) intron for plant DNA barcoding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kress WJ, Wurdack KJ, Zimmer EA, Weigt LA, Janzen DH. Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8369–8374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503123102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim N, Lee C. QPRIMER. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2331–2333. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bode M, Khor S, Ye H, Li M-H, Ying JY. TmPrime: fast, flexible oligonucleotide design software for gene synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W214–W221. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bekaert M, Teeling EC. UniPrime: a workflow-based platform for improved universal primer design. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duitama J, Kumar DM, Hemphill E, Khan M, Mandoiu II, Nelson CE. PrimerHunter: a primer design tool for PCR-based virus subtype identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2483–2492. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarman SN. Amplicon: software for designing pcr primers on aligned dna sequences. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1644–1645. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karp RM, Miller RE, Rosenberg AL. STOC '72: Proceedings of the fourth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 1972. pp. 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCreight EM. A space-economical suffix tree construction algorithm. J. ACM. 1976;23:262–272. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manber U, Myers G. SODA '90: Proceedings of the first annual ACM-SIAM symposium on Discrete algorithms. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; 1990. pp. 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurtz S, Schleiermacher C. REPuter: fast computation of maximal repeats in complete genomes. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:426–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.5.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Achaz G, Boyer F, Rocha EPC, Viari A, Coissac E. Repseek, a tool to retrieve approximate repeats from large DNA sequences. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:119–121. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dijkstra EW. Smoothsort, an alternative for sorting in situ. Sci. Comput. Program. 1982;1:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu S, Manber U. In Proceedings USENIX Winter 1992 Technical Conference. 1992. Agrep, a fast approximate pattern-matching tool; pp. 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santalucia J, Hicks D. The thermodynamics of DNA structural motifs. Annu. Rev. Biophys. BioMol. Struct. 2004;33:415–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.141800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kersey P, Bower L, Morris L, Horne A, Petryszak R, Kanz C, Kanapin A, Das U, Michoud K, Phan I, et al. Integr8 and Genome Reviews: integrated views of complete genomes and proteomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D297–D302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Needleman SB, Wunsch CD. A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1970;48:443–53. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edwards RA, Rodriguez-Brito B, Wegley L, Haynes M, Breitbart M, Peterson DM, Saar MO, Alexander S, Alexander EC, Jr, Rohwer F. Using pyrosequencing to shed light on deep mine microbial ecology. BMC Genom. 2006;7:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brownstein MJ, Carpten JD, Smith JR. Modulation of non-templated nucleotide addition by Taq DNA polymerase: primer modifications that facilitate genotyping. Biotechniques. 1996;20:1004–1006. doi: 10.2144/96206st01. 1008–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magnuson VL, Ally DS, Nylund SJ, Karanjawala ZE, Rayman JB, Knapp JI, Lowe AL, Ghosh S, Collins FS. Substrate nucleotide-determined non-templated addition of adenine by Taq DNA polymerase: implications for PCR-based genotyping and cloning. Biotechniques. 1996;21:700–709. doi: 10.2144/96214rr03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soininen EM, Valentini A, Coissac E, Miquel C, Gielly L, Brochmann C, Brysting AK, Sonstebo JH, Ims RA, Yoccoz NG, et al. Analysing diet of small herbivores: the efficiency of DNA barcoding coupled with high-throughput pyrosequencing for deciphering the composition of complex plant mixtures. Front Zool. 2009;6:16. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palumbi S, Martin A, Romano S, McMillan W, Stice L, Grabowski G. The Simple Fool's Guide to PCR, Version 2.0. Honolulu: University of Hawaii; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hebert PDN, Ratnasingham S, deWaard JR. Barcoding animal life: cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 divergences among closely related species. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2003;270:S96–S99. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Opik M, Metsis M, Daniell TJ, Zobel M, Moora M. Large-scale parallel 454 sequencing reveals host ecological group specificity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in a boreonemoral forest. New Phytol. 2009;184:424–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Porazinska DL, Giblin-Davis RM, Faller L, Farmerie W, Kanzaki N, Morris K, Powers TO, Tucker AE, Sung W, Thomas WK. Evaluating high-throughput sequencing as a method for metagenomic analysis of nematode diversity. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009;9:1439–1450. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]