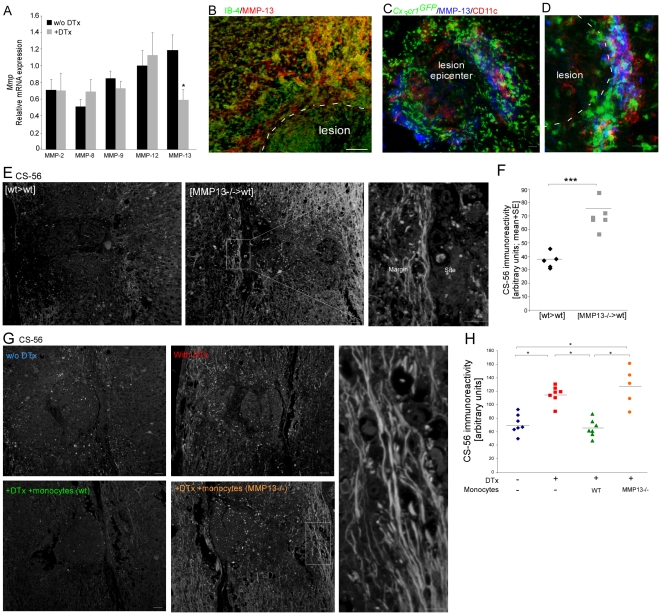

Figure 4. Infiltrating monocytes resolve glial scar matrix accumulation via the production of matrix metalloproteinase 13.

(A) Analysis of expression of various Mmp genes in excised spinal cord tissues of [CD11c-DTR:Cx3cr1 GFP/+>wt] BM chimeras, with or without DTx treatment. (B–D) Immunohistochemical labeling of the injured spinal cord sections of [Cx3cr1 GFP/+>wt] BM chimeric mice for MMP-13, together with IB-4 (B), or GFP and CD11c (C; D). (E,F) [wt>wt] or [MMP-13−/−>wt] BM chimeras were subjected to spinal cord injury 8 weeks following transplantation, and analyzed 14 days post trauma for CSPG immunoreactivity. Representative pictures are presented in E. Quantification of CS-56 (CSPG) immunoreactivity in 2 mm2 sections, including the lesion site margin and surrounding parenchyma is shown in F. Deficiency in MMP-13 resulted in increased accumulation of CSPG (Student's t-test; ***p = 0.0002). (G,H) [CD11c-DTR>wt] BM chimeric mice were subjected to spinal cord injury 8 weeks following BM transplantation. Four groups were used: one group left untreated, one group was treated with DTx alone, and the other two groups received DTx in parallel to transfer with DTx-resistant monocytes isolated from either wt or MMP-13 KO mice; CSPG immunoreactivity was evaluated 14 days post injury. Representative pictures are shown in G. Quantification is shown in H (ANOVA; F3,22 = 15.4; p<0.0001). While reconstitution with wt monocytes restored the regulation of CSPG accumulation, MMP13−/− monocytes failed to do so. Scale bar representation; 50 µm.