Abstract

Fibrillar collagens form the structural basis of organs and tissues including the vasculature, bone, and tendon. They are also dynamic, organizational scaffolds that present binding and recognition sites for ligands, cells, and platelets. We interpret recently published X-ray diffraction findings and use atomic force microscopy data to illustrate the significance of new insights into the functional organization of the collagen fibril. These data indicate that collagen’s most crucial functional domains localize primarily to the overlap region, comprising a constellation of sites we call the ‘master control region’. Moreover, collagens most exposed aspect contains its most stable part - the C-terminal region that controls collagen assembly, cross-linking, and blood clotting. Hidden beneath the fibril surface exists a constellation of ‘cryptic’ sequences poised to promote hemostasis and cell-collagen interactions in tissue injury and regeneration. These findings begin to address several important, and previously unresolved, questions: How functional domains are organized in the fibril, which domains are accessible, and which require proteolysis or structural trauma to become exposed. Here we speculate as to how collagen fibrillar organization impacts molecular processes relating to tissue growth, development, and repair.

Keywords: collagen, fibril, extracellular matrix, cell adhesion, hemostasis

Fibrillar collagens, of which types I and II are among the most common, are synthesized as soluble procollagens (1). They are composed of globular C- and N-propeptides, joined to their respective ends of the triple-helix. Upon secretion, the propeptides are cleaved by C- and N-proteinases leaving short, non-helical telopeptides, and a central triple-helical domain. The collagen monomer is then assembled into the collagen fibril, an aggregated form of collagen (1, 2). The collagen fibril apparently consists of microfibrils, or 5-mer bundles of overlapping monomers (3–7). Adjacent monomers overlap each other by 234 residues, giving rise to the 67 nm ‘D-period’, the basic repeat structure of the fibril. Hence, the D-periodic microfibril provides a simple model for assessing the fibril structure-function relationship, in particular when appreciating the architecture and accessibility of key ligand and cell interaction sites (3, 8–11).

We recently mapped human protein sequences of the collagen monomer onto the 67 nm staggered arrangement (9, 10) described above, also known as the Hodge-Petruska/Chapman scheme (4, 12) (see accompanying review article and Fig. 1). Known ligand binding, functional elements, and human substitution mutations were superimposed onto these sequences and we identified three major ligand binding regions and novel mutation patterns on the fibril. The distribution of functional sites and mutations suggested a domain model of the collagen fibril D-period, where dynamic aspects of collagen biology are coordinately regulated by cell-integrin interactions and collagen remodeling in the cell interaction domain. This domain is flanked by fibril zones performing structural duties, such as intermolecular cross-linking, proteoglycan (PG) binding, and mineralization. On a revised collagen map (10) it was recently noted that a relatively narrow fibril zone (the overlap regions) harbors all the cell interaction domain elements, and most other major functional domains, including the intermolecular cross-link sites, GFOGER, the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) cleavage sequence, the fibronectin binding site, the putative triple-helix nucleation domain, and the GPVI binding site GPO(5), P986, the substrate for prolyl-3 hydroxylation, and adjacent fibrillogenesis control sequences. We have therefore called this the ‘master control region’ (MCR) of the fibril (see accompanying review article). We explore the architecture and availability of these domain elements in the collagen fibril under different physiological circumstances in hypothetical “static” and “dynamic” fibril models. We present Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) data to help illustrate how key functional regions of the fibril localize relative to its convoluted surface structure.

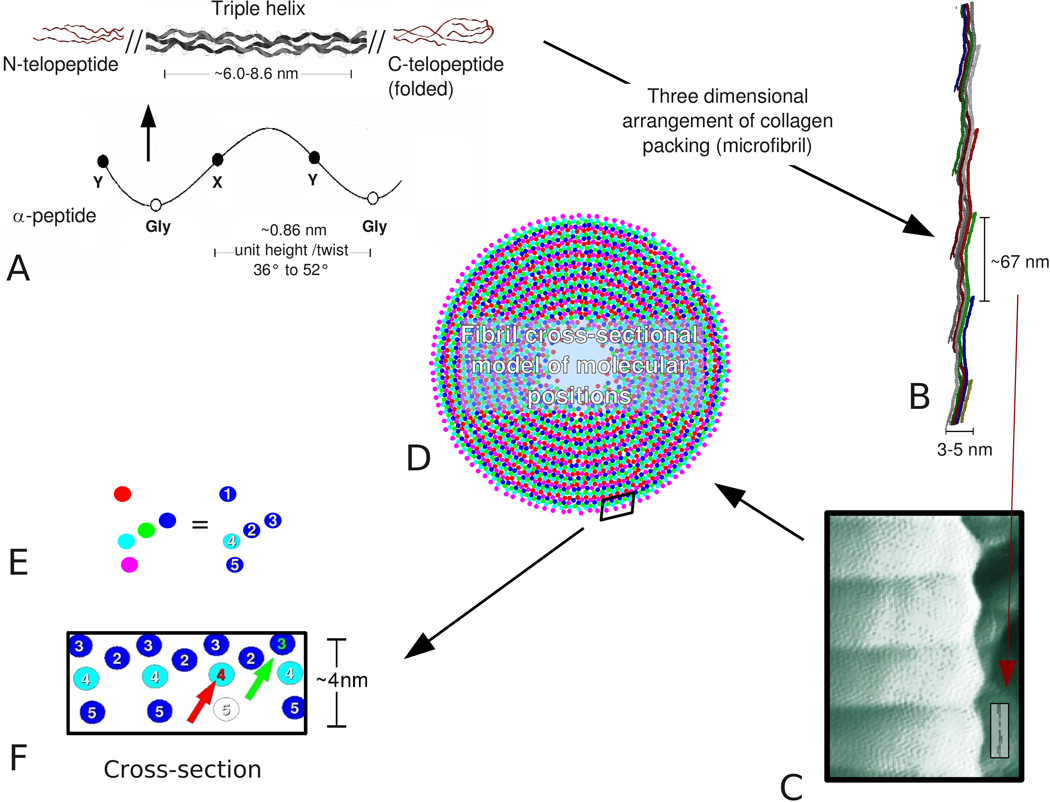

Figure 1. Summary of known structural features of fibrillar collagen (hierarchy from polypeptide to fibril).

A. The collagen-forming polypeptide chains contain a large helix-forming domain with the repeat amino acid sequence Gly-X-Y, where X and Y are occupied by Pro or Hyp more frequently than other residues, but account for approximately 1/6 of the total amino acid content (see for instance human sequence: ExPASy sequence data bank codes; P02452 and P08123). An arrow points to the figure element that shows that three polypeptides form the collagen monomer. The large triple helix (super-helix) domain of approximately 300 nm in length is flanked by non-helical telopeptides (N and C, shown). The 6–8.6 nm dimension indicates the repeat of the triple-helix (36, 37). B. Collagen molecules are staggered approximately 67 nm from one another in the formation of microfibril aggregates. The microfibrils are D-periodic (D=67 nm), and in each D-period, two monomers coil, or partially coil, around each other giving the appearance of another helix-like feature in the structural hierarchy (3). Note that the structure of the microfibril is ridged or corrugated, compared with (C). C. Profile of the type I collagen fibril recorded by atomic force microscopy (AFM) before dehydration of the fibril under air. Compared with D, note corrugations, termed "hills and valleys" in the main text. Hills refer to the raised parts and valleys to the dips (into the fibril), as seen via the edge profile. The insert shows one D-period of the microfibril to scale for comparison. D. Cross-sectional view of the collagen molecular packing of a type I collagen fibril (11). Each colored circle represents one collagen molecule in cross-section (at the axial level of the matrix metalloproteinase [MMP] collagenase cleavage-site). E. Cross-section of an isolated microfibril at the 0.44 D position. Color code matches that used in D and shows segment numbering for element F (note that M1 is not shown in F). F. Expanded view from the box in D. Colors of molecule cross-sections are changed to highlight M4 (location of collagenase cleavage site, yellow arrow). Green arrow marks the location of the integrin binding sequence GFOGER in the molecular packing, on M3. Note that both the collagenase binding domain and integrin binding sequence are partially buried until the C-terminus and/or M5 or M4 are moved aside or removed. Figure elements B, D-F are adapted from (3, 11).

Experimental procedures

Fibril surface model and microfibril orientation

The structure of the fibril surface was constructed, as described previously (11, 13), by convolution of the coordinates for the collagen microfibril (RCSB 3HR2) with the fibrillar packing lattice. A model of four neighboring microfibrils along the ‘3.8’ nm crystal lattice plane was generated after this fashion for one D-period (Fig. 2).

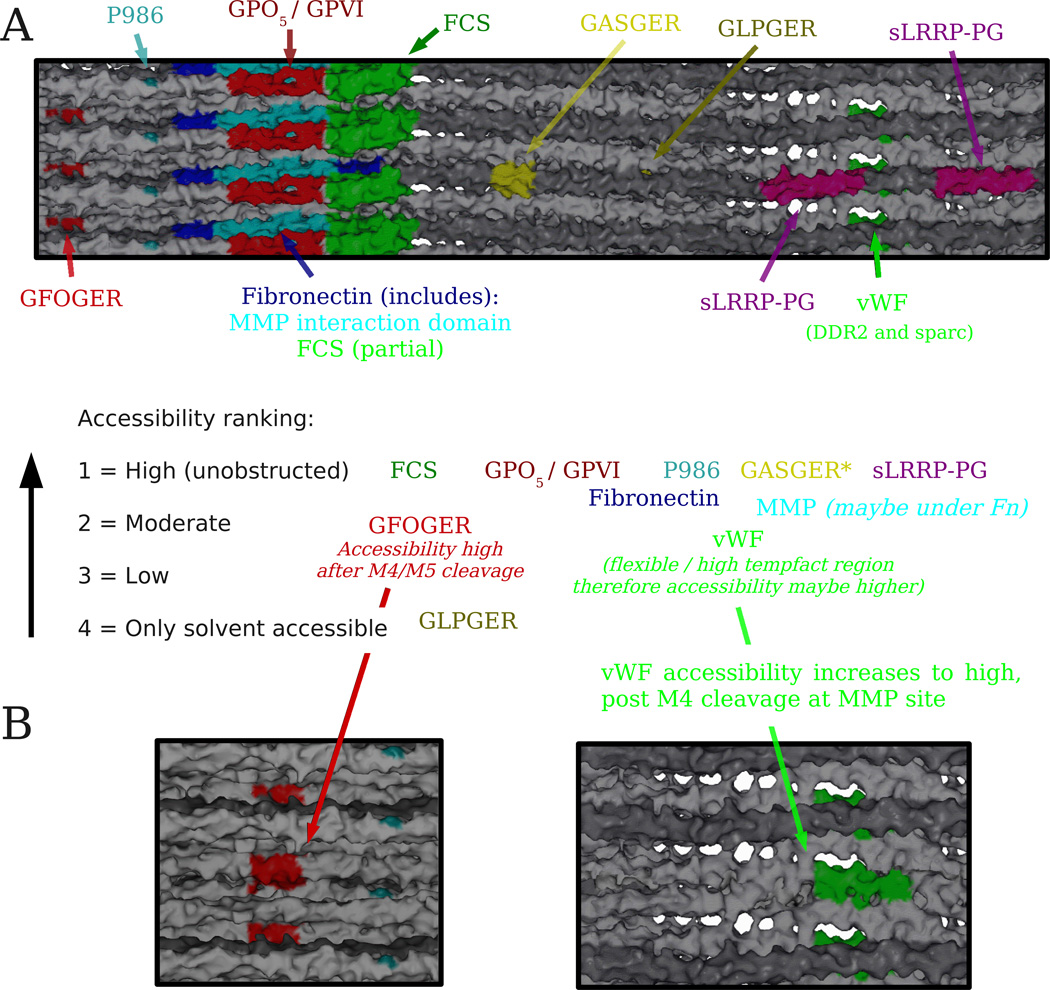

Figure 2. Ranking of ligand accessibilities to crucial binding sites and functional domains in the native and proteolyzed fibril.

A. Key functional domains of collagen were mapped onto a model of the fibril surface viewed from the fibril’s exterior. The model includes partial overlap and gap zones of a single D-period segment of a fibril comprised of four microfibrils. A qualitative molecular ‘accessibility’ ranking of various ligands to their respective binding sites was determined for the static fibril, and following matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) cleavage of M4. B) View of the fibril’s vWF binding site and surrounding area following MMP cleavage of M4.

The orientation of the microfibril along the 3.8 nm lattice followed the precedent of previous studies (11, 14, 15). For type I collagen, because the 'X3' ridge (14) aligns with the C-terminus of the collagen monomers, the 'highest' ridge is at the C-terminal part of each D-period (Figs. 1 and 3). This is also consistent with the fact that the C-terminal binding monoclonal antibody, regularly used by researchers to distinguish type I collagen in vivo from other collagen types (16), attaches to fibrillar collagen. Alternate fibril models would render this antibody’s epitope (near the C-terminus of collagen) buried and inaccessible (17).

Figure 3. Surface topology and functional architecture of the native collagen fibril.

A. By high resolution atomic force microscopy (AFM), rat tail tendon fibril surfaces resemble cables comprised of overlap zones which appear as the bright raised bands (the apex of each D-period being a white band, the X3 ridge, corresponding to the C-terminus), and gap zones, which appear as darker, recessed regions. Considering the relationship between fibril surface topology and collagen polarity (B), the borders of the MCR of the collagen microfibril (Figs. 1 and 2) were mapped relative to the fibril surface (B is an edge detected rendering of a native type collagen AFM image). The region of the overlap zone projecting furthest outward was found to coincide with the C-terminal end of the (11) MCR (red rectangle, A). The most structurally stable part, GPO(5), a likely candidate for initial platelet association, also localizes to a highly accessible region of the fibril (red dot), and apex of fibril surface (green arrow). B) The positions of the C- and N- termini of collagen monomers, determined in reference (11), are indicated on an edge-enhanced profile of the fibril surface. C) AFM of lamprey notochord, type II collagen shows a similar surface topology to that of type I collagen (compare A and B). Note these are collagen type II fibers rather than fibrils, i.e. bundles of fibrils. However, the ridged structure is preserved.

Molecular surface rendering and accessibility score

Surface rendering was performed, as described in two previous publications (11, 13) using Spock (18). Key structural features reported previously (10) were located in the model coordinates by amino acid sequence and sequence number and colored in the molecular scene rendering so that they may be differentiated. Ranking relative molecular accessibility was determined by estimating the relative depth of the sequence carrying the ligand binding amino acid sequence from the calculated molecular surface of the fibril. If not directly at the surface, the space between collagen monomers that allow access to the sequences was estimated: A relative ranking based on one molecular collagen diameter (score of one), and one eighth of this (score of four), were used to give an approximate grade of accessibility. A score of four implies only solvent accessibility, a score of one suggests a site is unobstructed, or nearly so.

Sample preparation

Sample preparation was similar to that described elsewhere (19). Briefly, type I collagen fibrils were harvested from rat tail tendons via pull dissection (tail ends are cut and vertebrae are snapped, and tendons removed with a gentle pull). Type II collagen fibrils were obtained from the notochords of adult lampreys, and carefully dissected from their sheaths (from nearby muscle and other tissues). Thin fibers were gently tweezed from each tissue and stored in PBS or TBS (physiological pH) for 1 to 6 h at 4°C before imaging experiments.

Atomic force microscopy

Type I fibrils were pipetted from the teased fiber ‘pull dissection’ suspension (described above), washed in distilled water and mounted on clean glass slides before they dried out. Images were acquired with a PicoScan-3000 AFM (Molecular Imaging Co., Tempe, AZ) and Multi-Mode NanoScope(R) IIIa AFM (Veeco Metrology, Santa Barbara, CA) using commercially available sharp tips in contact or tapping mode.

Type II fibrils were pipetted from the teased dissection suspension, described above, washed in distilled water, and placed onto a 1×1 cm2 clean plastic square, pre-cut from a cell culture dish, and the sample mounted onto the AFM sample stage for imaging. Imaging was carried out in fluid-tapping mode using a multimode Nanoscope IIIa AFM (Veeco Metrology), equipped with a J-scanner, using single crystal silicon tips at a resonance frequency of 300–350 kHz.

Labeling of AFM amplitude image data with key surface features

The location of the X3 and X2 ridges correspond to the C and N-termini respectively (20) (labeled in Fig. 3). The X2 ridge is small and not always apparent but its location is at the edge of the dip of the D-period. The X3 ridge is clearly pronounced and its location is at the apex of the D-period (20) within the A-band. The approximate location of the GPO(5) site was calculated on the basis of its percentage D-periodic position relative to the C-terminus (X3 ridge), and Figure 2 was labeled accordingly after comparison with the published data (20).

Results and Discussion

Architecture and biology of the fibril

We visualized how the elements of the MCR are arranged within the microfibril and fibril in situ (3, 11). Relevant functional domains on the triple-helices were color shaded and their accessibilities from the fibril surface (composed of closely packed microfibrils) were ranked (Fig. 2). These data are discussed from the perspective of fibrils in the "static", or intact state, as well as the "dynamic" states of fibril assembly, mechanical processes, thermal motion, or remodeling by proteases.

Static fibril

Fig. 2 shows that the crucial MCR elements occupy a relatively narrow region of the D-period, the overlap region (see also Fig. 3 and (10)). The C-terminus, due to its location relative to several key collagen amino acid sequences, may stabilize and protect the part of the D-periodic fibril surface that is most exposed to the extracellular environment (Figs. 1 and 2). This region, directly around and underlying the C-terminus, includes the collagen sequences that control fibril stability and assembly, such as cross-links mediating intermolecular (type I to type I and type V collagen's), as well as heterotypic associations (21), P986, a residue implicated in collagen assembly and crucial ligand interactions (22), and the triple-helix nucleation domain GPO(5) (23). This latter domain is the longest GPO repeat found in the collagen sequence and, due to its high imino acid content, is presumed to be more stable than the rest of the triple-helix. Its location, at the peaks of each of the microfibril’s repeating segments, or D-periods, might serve as a 'cap' to protect the less stable sequences located underneath the fibril surface (Fig. 2).

GPO(5) is also a putative platelet glycoprotein VI binding site (24). Platelet ligation of collagen is proposed to be a multistep process (25), however, peptides containing multiple GPO repeats directly support platelet adhesion and activation (24). This implies that GPO(5) is ‘platelet-active’, especially when presented on the multimeric fibril surface, as it is in our structure (11) (Figs. 2 and 3).

The remainder of the D-period at the fibril surface, which comprises mainly the matrix interaction domain, harbors the principal small leucine rich repeat protein (sLRRP) PG core protein interaction sites in the D and E band regions on M4. We recently confirmed these sites, albeit in silico, to be both accessible and favorably bound by decoron (13, 26) (Fig. 2). We surmise that the PGs and their prominent anionic glycosaminoglycan (AGAG) chains likely dominate or exclude interactions of other ligand types within this region (10). Thus, the entire span of the fibril surface in each D-period displays a predominantly structural, ‘tough’ face (that is, its most stable aspect is presented to the milieu). However, a potential exception is that of the three putative integrin binding sequences of the fibril (10, 27, 28), GASGER, is the only one that appears to be surface-accessible in the static fibril (Fig. 2). However, it is a relatively weak ligand binding site and is located in the matrix interaction domain, where its accessibility may be significantly modulated by fibril-associated PGs or mineralization (10).

Dynamic fibril

The fibril surface partially obscures, and may thus regulate, the accessibility of other elements of the MCR, including the underlying fibronectin binding site, the MMP cleavage site, and sequences for integrin and von Willebrand’s factor (vWF) binding, and platelet aggregation (Fig. 2). Whether these hidden sites have biological roles may depend on the physiological context. We previously proposed that selective proteolysis, or molecular disorganization resulting from physical or chemical trauma to, or bending of the fibril, may expose cryptic, specialized functional sites (11). For example, under certain conditions the C-terminus may be moved aside, or removed, and the MMP cleavage site on the underlying triple-helix become exposed to proteolytic attack (11, 29). This may depend on whether fibronectin masks the protease cleavage site. Slightly deeper into the fibril, and under the layer of collagen monomers removed with the initial fibril proteolysis (11), lies GFOGER (Fig 1) and the vWF binding site that promotes platelet aggregation and activation (Fig. 2). GFOGER is considered a high affinity integrin binding site for endothelial, epithelial, cartilage, and bone cells, and platelets. Thus, cell/GFOGER interactions likely occur, not with the static fibril, but rather during collagen fibril assembly, where the integrin binding site on the collagen monomer may be exposed, or in fibril remodeling, in response to proteolysis or tissue injury. Moreover, the fact that the fibril harbors at least three sequences to promote platelet activation on its surface, or at various depths within, highlights hemostasis as among collagen’s most prominent functions. On the other hand, since the circumstances of tissue injury may be so variable, multiple platelet-interactive sites may exist for the sake of functional redundancy, rather than for their requisite co-ordinate or sequential roles in hemostasis.

Several lines of evidence support the concept that proteolytic action may be a prerequisite for cell/collagen interactions (11, 30, 31). For instance, MMPs-1 and -2 (32) are involved in collagen fibril association with platelets. Given the proximity of the GPVI binding site to the C-terminus and underlying MMP-interaction domain, it is plausible that initial platelet-fibril associations may lead to collagenolysis of collagen monomer 4 (M4) that partially obscures the remaining platelet association sequences, including those for vWF and integrin ligation. Of note is that under pathological circumstances, C-terminal telopeptide release is a hallmark of matrix remodeling (33, 34). Without the removal of M4, the binding sites for the α1/α2β1 integrin I-domain (i.e., GFOGER) and vWF are partially obscured, although the vWF site is in a region of the fibril and collagen molecule given to fluctuations in molecular conformation (3, 11, 35) that could increase its surface accessibility However, removal or peeling away of M4 from the microfibril/fibril surface (a single collagen monomer cleavage event) leaves the GFOGER and vWF binding sites available for interactions with their macromolecular binding partners (11). Thus, the crucial matrix organizing regions of fibrillar collagen are generally accessible to large molecular ligands at the fibril surface, but other key ligand binding sites are less available until ‘proteolytic functionalization’ occurs. Therefore, we suggest that the ‘tough’ face of the collagen fibril is designed to protect these functional sites, until specific circumstances for their use arise.

With respect to the relative inaccessibility of the portions of the collagen monomer buried in the preferred orientation (see methods) (11), it is also worth considering the following points:

[1] The collagen molecule, and therefore the fibril is not a static structure; there is both disorder and thermal motion to consider in the packing of the molecules. This allows some leeway from the crystalline structure determined from the most ‘perfectly’ ordered parts of rat-tail tendon fibrils. [2] There are significantly fewer ligand-binding sites on the N-terminal half (particularly M1) of the collagen molecule than the C-terminal half. Perhaps these more ‘buried’ sites at the N-terminal end are less relevant to 'steady-state' fibril-ligand interactions than they are to fibrillogenesis/fibril proteolysis. [3] Limited proteolytic activity may periodically expose these sites and the extent to which this happens may also be highly tissue specific. In fact, we suggest that the collagen fibril may be functionalized via limited proteolysis as a step analogous to the removal of pro-peptides from smaller proteins or complexes for their functional activation. [4] Monomeric collagen that is not associated into microfibrils may periodically sit in the grooves outlined on the fibril surface between the successive M5s (overlap) and M4s (gap), (see Fig. 2). If so, it is also possible that this may be the localization site for other fibril associating collagens (such as collagen type V). This allows for the type I-type V crosslink, mapped to the Cterminus, to be available to the fibril surface [5]. All of the above may apply simultaneously to greater or lesser degree depending upon specific circumstances.

Collagen puts its tough face forward

The positions of key functional elements were localized relative to the surface of the native collagen fibril using AFM data (Figs. 2 and 3). Fibrils viewed in this way show ‘up-ward slopes’ corresponding to the fibril’s overlap zones, and ‘downward slopes’ representing its gap zones. These appear as ‘hills’ and ‘valleys’ in Figs. 2 and 3, each of which are composed of two parts of neighboring D-periods. The ‘peak’ or apex of each hill represents the C-terminus of the outermost microfibril layer of the fibril. The C-terminal portion of the microfibril’s MCR was found to form the apex of the overlap zone, the D-periodic fibril portion that protrudes farthest into the surrounding milieu. Thus, the region that is likely the ‘toughest’ i.e. most structurally stable part of the collagen fibril, is the most exposed. The gap region, which harbors and may be dominated by the sLRRP PGs, and structural macromolecules, can be envisioned to maintain a low surface profile within the valleys of the fibril surface (3, 13). Yet, collagen’s tough face masks a softer side, remaining poised to promote blood clotting in response to injury, and to reveal a constellation of sites crucial for tissue healing and regeneration.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant #MCB-0644015 CAREER) and the National Institutes of Health (grant #RR-08630). This material is based upon work supported by, or in part by, the U. S. Army Research Laboratory and the U. S. Army Research Office under contract/grant number W911NF 09-1-0378.

Footnotes

Potential Conflict of Interest: JDS is an employee of Orthovita Inc.

References

- 1.Ayad S, Boot-Handford R, Humphries M, Kadler K, Shuttleworth C. The extracellular matrix Facts Book. Academic Press; 1998. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kadler K, Baldock C, Bella J, Boot-Handford R. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1955–1958. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orgel J, Irving T, Miller A, Wess T. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9001–9005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502718103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petruska J, Hodge A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1964;51:871–876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.51.5.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bear R. Adv Protein Chem. 1952;7:69–160. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes D, Gilpin C, Baldock C, Ziese U, Koster A, Kadler K. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7307–7312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111150598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman J. Connect Tissue Res. 1974;2:137–150. doi: 10.3109/03008207409152099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Twardowski T, Fertala A, Orgel J, San Antonio J. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:3608–3621. doi: 10.2174/138161207782794176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Lullo G, Sweeney S, Korkko J, Ala-Kokko L, San Antonio J. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4223–4231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sweeney S, Orgel J, Fertala A, McAuliffe J, Turner K, Di Lullo G, Chen S, Antipova O, Perumal S, Ala-Kokko L, Forlino A, Cabral W, Barnes A, Marini J, Antonio J. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21187–21197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709319200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perumal S, Antipova O, Orgel J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2824–2829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710588105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman J, Hardcastle R. Connect Tissue Res. 1974;2:151–159. doi: 10.3109/03008207409152100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orgel JPRO, Eid A, Antipova O, Bella J, Scott JE. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hulmes D, Jesior J, Miller A, Berthet-Colominas C, Wolff C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:3567–3571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hulmes D, Wess T, Prockop D, Fratzl P. Biophys J. 1995;68:1661–1670. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80391-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werkmeister J, Ramshaw J, Ellender G. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1990;187:439–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herr AB, Farndale RW. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19781–19785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.013219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christopher J, Swanson R, Baldwin T. Comput Chem. 1996;20:339–345. doi: 10.1016/0097-8485(95)00075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orgel J, Wess T, Miller A. Structure Fold Des. 2000;8:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raspanti M, Alessandrini A, Gobbi P, Ruggeri A. Microscopy Research And Technique. 1996;35:87–93. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19960901)35:1<87::AID-JEMT8>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruckner P. Cell and Tissue Research. 2010;339:7–18. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0864-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morello R, Bertin TK, Chen Y, Hicks J, Tonachini L, Monticone M, Castagnola P, Rauch F, Glorieux FH, Vranka J, Bächinger HP, Pace JM, Schwarze U, Byers PH, Weis M, Fernandes RJ, Eyre DR, Yao Z, Boyce BF, Lee B. Cell. 2006;127:291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyde TJ, Bryan MA, Brodsky B, Baum J. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:36937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smethurst PA, Onley DJ, Jarvis GE, O'Connor MN, Knight CG, Herr AB, Ouwehand WH, Farndale RW. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:1296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahn ML. Seminars in Thrombosis & Hemostasis. 2004. Platelet-Collagen Responses: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Promise; p. 419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott J. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8795–8799. doi: 10.1021/bi960773t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Y, Gurusiddappa S, Rich R, Owens R, Keene D, Mayne R, Hook A, Hook M. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38981–38989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007668200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knight CG, Morton LF, Peachey AR, Tuckwell DS, Farndale RW, Barnes MJ. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:35–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenblum G, Van den Steen PE, Cohen SR, Bitler A, Brand DD, Opdenakker G, Sagi I. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sternlicht M, Werb Z. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2001;17:463–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rundhaug JE. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:267–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trivedi V, Boire A, Tchemychev B, Kaneider N, Leger A, O'Callaghan K, Covic L, Kuliopulos A. Cell. 2009;137:332–343. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pater A, Sypniewska G, Pilecki O. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;23:81–86. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2010.23.1-2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villarreal F, Omens J, Dillmann W, Risteli J, Nguyen J, Covell J. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2004;36:597–601. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan P, Li M, Brodsky B, Baum J. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13299–13309. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rainey J, Goh M. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2748–2754. doi: 10.1110/ps.0218502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bella J. J. Struct. Biol. 2010;170:377–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]