Abstract

The Database for Bacterial Group II Introns (http://webapps2.ucalgary.ca/~groupii/index.html#) provides a catalogue of full-length, non-redundant group II introns present in bacterial DNA sequences in GenBank. The website is divided into three sections. The first section provides general information on group II intron properties, structures and classification. The second and main section lists information for individual introns, including insertion sites, DNA sequences, intron-encoded protein sequences and RNA secondary structure models. The final section provides tools for identification and analysis of intron sequences. These include a step-by-step guide to identify introns in genomic sequences, a local BLAST tool to identify closest intron relatives to a query sequence, and a boundary-finding tool that predicts 5′ and 3′ intron–exon junctions in an input DNA sequence. Finally, selected intron data can be downloaded in FASTA format. It is hoped that this database will be a useful resource not only to group II intron and RNA researchers, but also to microbiologists who encounter these unexpected introns in genomic sequences.

INTRODUCTION

Group II introns are a class of mobile DNAs consisting of a catalytic RNA (ribozyme) and an intron-encoded protein (IEP). The ribozyme component catalyzes self-splicing in vitro, at least for some introns, while the IEP promotes splicing reaction either in vivo, or under physiological conditions in vitro. The IEP also allows the intron to be mobile and insert into new genomic locations. The biochemical mechanisms for splicing and mobility reactions have been covered in detail in a number of review articles (1–9).

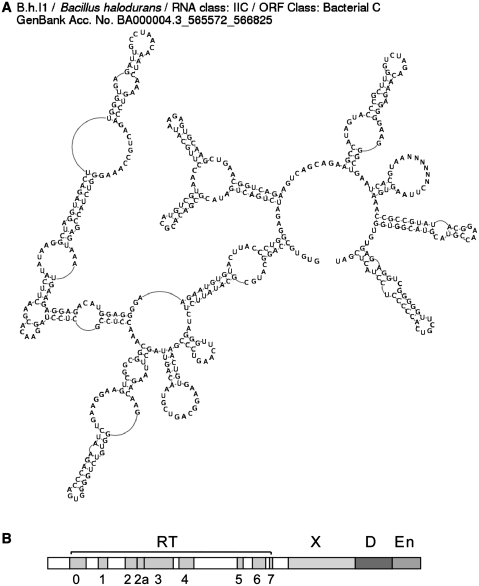

Despite having variable primary sequences, group II RNAs fold into a conserved secondary structure that consists of six domains (DI –DVI) emanating from a central wheel (Figure 1A) (10). Domain I is the largest domain, while domain V contains catalytic residues and domain VI contains a bulged adenosine motif that is analogous to the branchpoint of spliceosomal introns. Within a large loop of domain IV is an open reading frame (ORF) encoding the IEP (Figure 1A,B). The IEP is a multifunctional protein containing a reverse transcriptase (RT) domain that is comprised of seven sequence blocks conserved across RT families. Downstream domains include the X/thumb domain that contributes maturase (splicing) function, a DNA-binding domain (D), and an endonuclease (En) domain, with the latter two being involved in the mobility reaction. The D domain is not highly conserved in sequence among group II introns, while the En domain is absent from many introns.

Figure 1.

Group II intron structure. (A) An example intron RNA secondary structure, as displayed by the website. Ns in the domain IV loop denote the long ORF sequence that is not shown. (B) Typical ORF structure of a group II intron IEP with domains for RT, X/thumb (maturase, or splicing function), D (DNA-binding) and En (endonuclease) (drawn to scale for the Ll.LtrB intron of Lactococcus lactis). Some lineages of introns lack the En domain, while domain D is a functional domain and not highly conserved in sequence.

Group II introns can be classified according to either ribozyme secondary structures or IEP sequences. Ribozyme structures are divided into IIA, IIB and IIC classes, based on characteristic secondary structure features and mechanisms of exon recognition (8–10). In contrast, the IEP classifications are phylogenetically based, and are denoted bacterial classes A, B, C, D, E and F, ML (mitochondrial-like), and CL1 and CL2 (chloroplast-like 1 and 2) (11–13). The two classification systems do in fact correspond, in that ML introns have IIA structures, bacterial C introns have IIC structures, and the rest have class-specific variations of IIB structures. All of these classes are present in bacteria.

Group II introns are distributed throughout eubacteria and archaebacteria, as well as chloroplasts and mitochondria of plants, fungi, protists and a few animals (2,4,14,15). Approximately a quarter of eubacterial genomes harbor at least one group II intron, whereas relatively few are found in archaebacteria. Despite the widespread occurrence of group II introns in bacterial genomes, they continue to be overlooked and misannotated in new sequences. A major goal of the website is to facilitate identification of introns in newly sequenced genomes by providing a reference set of correctly identified introns and varietal classes.

DATA GENERATION AND DATABASE CONTENT

The website was established in 2002 as a compendium of all bacterial group II introns in GenBank, which at that time totalled ∼40 introns (16). By 2011, the number has increased to almost 400 introns in the database (http://webapps2.ucalgary.ca/~groupii/index.html#). The curation process occurs through a semi-automated series of steps that first identifies an IEP, and then locates and folds the surrounding ribozyme (to be reported elsewhere). Manual proofreading and refinements are required to maintain the quality of the results. A complication in this process is the large number of truncated and inactivated introns in bacteria, which in fact, outnumber the full-length, functional introns. Reflective of this, a major change in the curation of the database is that the main table now only lists introns that are full-length and presumably functional for both splicing and mobility. Once an intron is deemed to be full-length and functional, a name is assigned based on a species abbreviation and intron number. Sequences that are >95% identical and in the same species are given the same name and listed only once in the table to avoid redundancy. As much as possible, names are consistent with published literature, and are not changed over time. However, name changes are inevitable when species names are changed in GenBank entries.

The database is divided into three major sections. The introductory section presents information on the basic splicing and mobility properties of group II introns, as well as RNA secondary structures, ORF structure, and the distribution and evolution of group II introns. Detailed consensus secondary structures are provided for IIA, IIB and IIC ribozyme classes, as well as the ribozymes of the IEP-based phylogenetic subclasses (ML, CL1, CL2, A, B, C, D, E and F). IEP domains are defined in a multi-sequence alignment.

In the main section, individual bacterial introns are presented in a table format, with columns denoting the intron names, species, host genes, genomic loci (e.g. plasmid, chromosome), ORF domains, ORF sizes (amino acids), ORF phylogenetic classes, RNA secondary structure classes and GenBank accession numbers. Links from accession numbers lead to corresponding GenBank entries. Links from the intron names open pages for individual introns, which show their DNA sequences, with intron and ORF boundaries denoted by colors, and also their predicted ORF sequences and RNA secondary structures. Both eubacterial and archaeal tables can be sorted by clicking on column headings. For example, one could sort the intron tables by species, ORF class, intron size, etc. to cluster introns based on those criteria.

Group II introns that do not encode ORFs are comparatively rare in bacteria genomes. Information on these introns is provided on a separate web page. Almost without exception, ORF-less introns in bacteria are found in genomes harboring a closely related ORF-containing intron, such that the IEP may act in trans on the ORF-less intron (13,17). It remains possible that ORF-less introns are more abundant than realized, because intron identification relies on initial identification of an IEP; however, a search for group II introns independently of the IEP did not identify significantly more ORF-less introns (13).

As previously noted, there is a large number of fragmented and/or inactivated group II introns in bacterial genomes, and we no longer attempt to document all of them. In order to represent some of these sequences, a table is shown of inactivated bacterial introns, which corresponds to an approximately complete listing as of 2005.

Group II introns in organelles differ from those in bacteria because they frequently lack IEPs and have degenerated secondary structures. The database does not display a complete listing of group II introns in mitochondria and chloroplasts. Instead, a sampling of mitochondrial and chloroplast ORF-containing introns is shown in two separate tables. Researchers are referred to GOBASE (18) and FUGOID (19) for further information on organellar introns.

TOOLS FOR IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS OF GROUP II INTRONS

The third section of the database offers tools for identification and analysis of group II introns. A step-by-step guide outlines a procedure to identify introns in genomic sequences. The newly implemented BLAST search tool allows one to locate the closest intron relatives in the database to a query sequence. The search returns the top 10 hits along with alignments between the query sequence and matching intron. In analyzing a candidate intron sequence, the closest relative is quite useful for determining the correct boundaries and secondary structure. The tool can also identify truncated introns, when there is an abrupt discontinuity in the alignment.

The boundary prediction tool predicts 5′ and 3′ intron boundaries in an input DNA sequence, based on sequence profiles of the intron–exon junctions for the different subclasses of introns (20). The tool makes conservative predictions, such that boundaries identified are likely to be correct, while 5′ and 3′ boundaries may be missed for introns that do not follow the consensus strictly. A test for prediction accuracy, using known intron sequences in the database, showed correct boundary prediction for 72% of introns, incorrect boundary predictions for 3% and no prediction for 25% of introns. Regardless of the computational outcome, predicted boundaries must be confirmed by folding the intron RNAs into secondary structures, and/or by verifying that the theoretical exons, when ligated, code for a functional protein.

Finally, selected intron data can be downloaded as FASTA format text files. Downloads can be requested for intron sequence, ORF sequence (DNA or amino acid) or intron sequence with flanking sequence, and can be selected according to phylogenetic class, genus, species, intron name or accession number. For example, one could download all class ML DNA sequences, all Bacillus IEP amino acid sequences, or all introns present in a given GenBank entry.

Undoubtedly, the number of known group II introns will continue to grow rapidly as more genomic and metagenomic samples are sequenced. With the increased functionality and new tools provided by the intron database, it is hoped that the resource will continue to aid RNA researchers and microbiologists alike.

FUNDING

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (grant number MOP-93662); Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (grant number RGP 203717-02); Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (salary support, to S.Z., in part); PGS-D studentship (from NSERC, to B.A.M.). Funding for open access charge: CIHR (Canada).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Michel F, Feral J. Structure and activities of group II introns. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995;64:435–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonen L, Vogel J. The ins and outs of group II introns. Trends Genet. 2001;17:322–331. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belfort M, Derbyshire V, Parker MM, Cousineau B, Lambowitz AM. Mobile introns: pathways and proteins. In: Craig NL, Craigie R, Gellert M, Lambowitz AM, editors. Mobile DNA II. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2002. pp. 761–783. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambowitz AM, Zimmerly S. Mobile group II introns. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004;38:1–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toro N, Jiménez Zurdo JI, García Rodríguez FM. Bacterial group II introns: not just splicing. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2007;31:342–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fedorova O, Zingler N. Group II introns: structure, folding and splicing mechanism. Biol. Chem. 2007;388:665–678. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehmann K, Schmidt U. Group II introns: structural and catalytic versatility of large natural ribozymes. Crit.Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;38:249–303. doi: 10.1080/713609236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michel F, Costa M, Westhof E. The ribozyme core of group II introns: a structure in want of partners. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009;34:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyle AM. The tertiary structure of group II introns: Implications for biological function and evolution. Crit.Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;45:215–232. doi: 10.3109/10409231003796523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michel F, Kazuhiko U, Haruo O. Comparative and functional anatomy of group II catalytic introns—a review. Gene. 1989;82:5–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimmerly S, Hausner G, Wu X-C. Phylogenetic relationships among group II intron ORFs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1238–1250. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.5.1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toro N, Molina-Sanchez MD, Fernández-López M. Identification and characterization of bacterial class E group II introns. Gene. 2002;299:245–250. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon D, Clarke NAC, McNeil BA, Johnson I, Pantuso D, Dai L, Chai D, Zimmerly S. Group II introns in Eubacteria and Archaea: ORF-less introns and new varieties. RNA. 2008;14:1704–1713. doi: 10.1261/rna.1056108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallès Y, Halanych KM, Boore JL. Group II introns break new boundaries: presence in a bilaterian's genome. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Copertino DW, Hallick RB. Group II and group III introns of twintrons: potential relationships with nuclear pre-mRNA introns. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1993;18:467–471. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90008-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai L, Toor N, Olson R, Keeping A, Zimmerly S. Database for mobile group II introns. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:424–426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng Q, Wang Y, Liu XQ. An intron-encoded protein assists RNA splicing of multiple similar introns of different bacterial genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:35085–35088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Brien EA, Zhang Y, Wang E, Marie V, Badejoko W, Lang BF, Burger G. GOBASE: an organelle genome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D946–D950. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li F, Herrin DL. FUGOID: functional genomics of organellar introns database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:385–386. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eddy SR. A new generation of homology search tools based on probabilistic inference. Genome Inform. 2009;23:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]