Abstract

The role of metabolism-excitation coupling in insulin secretion has long been apparent but, in parallel with studies of human hyperinsulinism and diabetes, genetic manipulation of proteins involved in glucose transport, metabolism and excitability in mice has brought the central importance of this pathway into sharp relief in recent years. We focus on these animal studies, and how they not only provide important insights to metabolic and electrical regulation of insulin secretion, but also to downstream consequences of alterations in this pathway, and to the etiology and treatment of insulin-secretion diseases in humans.

Keywords: Diabetes, transgenic, pancreas, mice, hyperinsulinism, hyperglycemia, genetic, β-cells

1. Introduction

Human diseases highlight the importance of β-cell metabolism-excitation (M-E) coupling

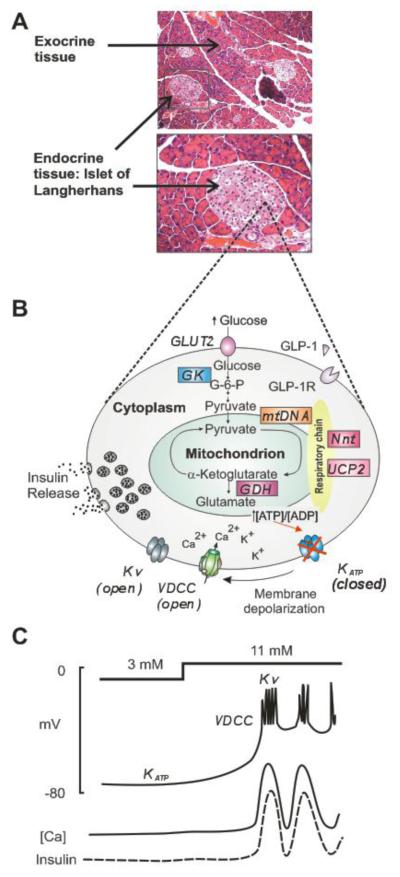

The pathway from glucose entry into the β-cell, through metabolism to electrical signaling and intracellular [Ca2+] (Fig. 1) is critical in control of insulin secretion, and it is becoming increasingly apparent that many of the relevant genes underlying human diabetes and hyperinsulinism are found in this pathway. Established steps in response to elevated blood glucose are uptake through glucose transporters, conversion to glucose-6-phosphate by glucokinase and metabolism to generate ATP. A rise in cytoplasmic [ATP]:[ADP] leads to ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel closure at the plasma membrane, which in turn results in membrane depolarization, opening of voltage-dependent Ca2+ and voltage-gated K+ channels (Dukes and Philipson, 1996; Philipson, 1999; Rorsman and Trube, 1986; Su et al., 2001). Calcium entry through Ca2+ channels results in increased intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i), which, in turn, triggers insulin exocytosis (Ashcroft and Rorsman, 1990; MacDonald et al., 2005).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the glucose stimulated insulin secretory pathway in β-cells.

A) Hematoxylin-eosin stained paraffin section of mouse pancreas. The pancreas is composed of exocrine tissue and endocrine tissue (Islet of Langerhans). Islets contain different cell types, including the insulin-secreting β-cells. Arrows point to exocrine and endocrine tissue. B) Schematic illustration of the β-cell glucose-stimulated insulin secretion pathway. Glucose entering the β-cell through glucose transporters (GLUT2) is phosphorylated by glucokinase (GK) and metabolized by glycolysis (Cytoplasm) and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (mitochondria). A rise in the [ATP]:[ADP] ratio resulting from oxidative metabolism inhibits the ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP) at the cell surface, causing membrane depolarization and opening of voltage-dependent Ca2+-channels (VDCC). This results in a rise of intracellular [Ca2+] which stimulates insulin secretion. Voltage-dependent outward K+ channel (Kv) are involved in membrane repolarization and cessation of insulin secretion. Factors that impair ATP production or downstream signaling are expected to suppress GSIS. Several genes that directly or indirectly alter ATP production and therefore underlie a diabetic or hypeinsulinemic phenotype when mutated (humans and/or mouse models) are shown in color: glucokinase (GK), nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (Nnt), uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2), mitochondrial DNA mutations (mtDNA) and glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH). Mutations that may indirectly affect channel activity are also shown in color. C) Schematic illustration of the electrical activity of β-cells and the temporal response to elevated glucose. In low (3 mM) glucose, the membrane is hyperpolarized due to KATP activity, intracellular Ca ([Ca]) is low and insulin is not secreted. When glucose is elevated to stimulatory levels (11 mM), KATP channels close, and the membrane depolarizes due to L-type VDCC activity. Bursts of APs, involving both VDCC and Kv channels, result in slowly elevated [Ca], which in turn triggers insulin secretion.

Congenital Hyperinsulinism of Infancy (HI), characterized by constitutive insulin secretion despite low blood glucose (Aynsley-Green, 1981), can result from abnormalities in several genes involved in M-E coupling, including loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in the KATP channel, and gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in glucokinase (GCK), glutamate dehydrogenase or short chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (Palladino et al., 2008). Conversely, Permanent and Transient Neonatal Diabetes Mellitus (PNDM, TNDM), can result from LOF mutations in glucokinase and GOF mutations in the β-cell KATP channel subunits (Smith et al., 2007). Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young 2 (MODY-2) results from weaker LOF mutations in GCK (Cuesta-Munoz et al., 2004; Gloyn et al., 2003), and monogenic diabetes caused by mitochondrial DNA mutation, results from defective β-cell secretion (Maassen, 2002). Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified multiple polymorphisms associated with type-2 diabetes (Cauchi et al., 2008; Sladek et al., 2007; Unoki et al., 2008; Yasuda et al., 2008; Zeggini et al., 2007) and again, many are in or near several genes that encode for proteins involved in β-cell M-E coupling directly, or indirectly via Ca-dependent processes. These include CAPN10 (calpain10, an intracellular calcium-dependent cysteine protease), SLC30A8 (a zinc transporter), KCNJ11 (the channel-forming subunit of the KATP channel) and KCNQ1 (pore-forming subunit of a voltage-gated K channel). Others, including CDKAL1, HHEX, HNF4A, IGF2BP2, PPARG and TCF7L2, are potentially involved in β-cell growth or proliferation and may indirectly affect insulin secretion (Pascoe et al., 2008; Stancakova et al., 2009).

Over the last ten years or so, while these genetic bases of human disease have been identified, detailed knowledge of in vivo β-cell function has come from genetically-modified mice. We focus on how these studies, in dissecting M-E coupling in vivo, inform islet function in the intact animal, and the dysfunctions that result in hyperinsulinism and diabetes. In many cases, different gene products fulfill similar roles in human and mouse β-cells, and extrapolation from mouse to man is not automatic. Nevertheless, emerging themes from mouse studies not only provide mechanistic insights to the metabolic regulation of insulin secretion and the downstream consequences of altered genes, but in many cases may directly predict and inform the etiology of the human diseases.

2. Mouse models of altered glucose uptake and glucose metabolism

Loss of membrane glucose transporters causes diabetes

Although both GLUT1 and GLUT2 isoforms may be present in human islets (Richardson et al., 2007). GLUT2 is the main isoform expressed in rodent pancreatic β-cells (Efrat et al., 1994; Thorens, 2001). Inactivation of GLUT2 (GLUT2−/−) in mice leads to severe hyperglycemia accompanied by high circulating fatty acids, and GLUT2−/− mice die within the first 3 weeks after birth (Guillam et al., 1997). Isolated islets show loss of first-phase and reduced second-phase glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) (Guillam et al., 1997), reflecting lack of glucose uptake into the β-cell. Re-expression of glucose transporters in GLUT2 knockout islets (using recombinant lentiviral expression or by crossing with mice overexpressing GLUT2 or GLUT1 under Rip control) restores normal GSIS (Guillam et al., 2000; Thorens et al., 2000)

Alterations in Glucokinase activity cause diabetes and hyperinsulinism

Following entry into the β-cell, glucose is phosphorylated by GCK and then metabolized through glycolytic and oxidative pathways (Matschinsky, 1996) (Fig. 1B). In humans, GOF mutations in either GCK or mitochondrial glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) cause HI, elevating [ATP]:[ADP] at any ambient glucose concentration and suppressing KATP channel activity (Page et al., 1992; Sakura et al., 1998). Reiterating key features, mice overexpressing yeast hexokinase (Epstein et al., 1992a) or the GCK gene itself (Shiota et al., 2001) are relatively hyperinsulinemic. Conversely, homozygous inactivating GCK mutations cause PNDM (Gloyn et al., 2003; Gloyn et al., 2002; Njolstad et al., 2001). Mice with deletion of the GCK gene in pancreatic β-cells and neurons but not in the liver (by targeted disruption of the appropriate exon 1 variant), showed severe perinatal diabetes, and died shortly after birth (Grupe et al., 1995; Terauchi et al., 1995). Confirming the critical role of β-cell GCK, transgenic re-expression only in β-cells reversed diabetes in ~50% of the mice (Grupe et al., 1995).

While homozygous LOF GCK mutations cause PNDM (Gloyn et al., 2003), heterozygous LOF mutations, resulting in only partial reduction of GCK activity, underlie MODY-2 (Cuesta-Munoz et al., 2004; Gloyn et al., 2003), characterized by impaired insulin secretion and diabetes onset in early adulthood, typically not worsening over time (Fajans et al., 2001). Heterozygous β-cell GCK+/− mutant mice show glucose-intolerance and impaired GSIS (Bali et al., 1995; Grupe et al., 1995; Sakura et al., 1998) but again, the diabetes does not progress, reiterating the MODY-2 phenotype. Why the phenotype is non-progressive, in humans and mice, is interesting, since the level of hyperglycemia that is reached (typically fasted blood glucose of ~ 125-135 mg/dL (Codner et al., 2006; Fajans et al., 2001; Shehadeh et al., 2005) is one that progresses to uncontrollable levels in other forms of diabetes, including human type-2 (Guillausseau et al., 2008; Matveyenko and Butler, 2008). Insulin levels are typically normal, such that decreased insulin/glucose ratio suggests increased insulin sensitivity, in humans and mice (Grupe et al., 1995; Katagiri et al., 1992; Terauchi et al., 1995). Chronic (48-96 hours) exposure of GCK+/− islets to high glucose concentration enhances glucose responsivity, whereas similar exposure of wild-type islets induces dysfunction(Sreenan et al., 1998). As we discuss below, an emerging idea from multiple transgenic animals is that secondary progression of diseases may depend critically on the underlying cellular mechanisms. ‘Underexcited’ islets, such as those with reduced metabolic flux, may respond well to chronic restoration of excitability, whereas ‘hyperstimulation’ of otherwise normal islets may be detrimental.

A first polygenic mouse model of non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (Terauchi et al., 1997) was obtained by crossing heterozygous GCK+/− mice (Terauchi et al., 1995) with homozygous insulin receptor substrate-1 knockout (IRS-1−/−) mice. Parental IRS-1−/− mice were insulin-resistant, but did not develop diabetes, due to compensatory β-cell hyperplasia (Araki et al., 1994; Tamemoto et al., 1994). Importantly, GCK+/−/IRS-1−/− mice showed hyperglycemia despite β-cell hyperplasia, and became overtly diabetic with age (Terauchi et al., 1997), experimentally confirming that genetic combination of insulin-resistance and reduced insulin secretion can lead to diabetes.

Any consequences of GCK-deficiency on electrical activity should be absent in animals that lack glucose-regulated KATP channels, and perinatal lethality was avoided in GCK−/−/Kir6.2−/− double knockout mice, although they were still insulin-deficient and still died prematurely (Remedi et al., 2005). However, heterozygous GCK+/− animals, that were markedly diabetic on the Kir6.2 wild-type background, became only mildly glucose-intolerant on the Kir6.2−/− background, essentially behaving like Kir6.2−/− mice (see below) (Remedi et al., 2005), confirming that a major feature of GCK-deficiency is indeed reduced excitability via enhanced KATP channel activity.

Alteration of mitochondrial proteins involved in regulation of ATP production and expenditure: indirect action via electrical signaling

Mitochondria provide the major ATP-generating capacity of β-cells (Erecinska et al., 1992; Maechler, 2001). Overactive mitochondrial metabolism will increase cytosolic [ATP]:[ADP], leading to closure of β-cell KATP channels and enhancing secretion (see below) (Fig. 1). Conversely, impaired mitochondrial metabolism will decrease [ATP]:[ADP], preventing KATP channel closure and suppressing secretion (Wallace, 2001). UnCoupling Proteins (UCPs) dissociate mitochondrial substrate oxidation from ATP synthesis (Fig. 1). UCP2 activation contributes to decreased reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation and free fatty-acid transport/metabolism, but mostly reduces the efficiency of ATP generation (Arsenijevic, 2000; Himms-Hagen and Harper, 2001; Nishikawa et al., 2000; Samec et al., 1998). UCP2 is present in β-cells and, consistent with above predictions, UCP2−/− mice demonstrate increased circulating insulin, without changes in peripheral insulin sensitivity (Joseph et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2001). UCP2−/− islets show increased [ATP] and hypersecretion of insulin at any glucose concentration (Joseph et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2001). When fed a high-fat diet, these mice show improved β-cell glucose-sensitivity, enhanced GSIS and increased insulin content (Joseph et al., 2002). Several animal models support the idea that UCP2 upregulation and consequent inefficient ATP production is a feature of gluco-lipotoxic conditions (Chan et al., 1999). Mice and rats fed a high-fat diet show up-regulation of UCP2 gene expression and elevated plasma lipids (Briaud et al., 2002; Chan et al., 2001). Fa/fa rats (leptin-receptor deficient) and ob/ob mice (leptin deficient) are popular models of obesity-induced diabetes, and both show up-regulation of UCP2 mRNA in β-cells (Kassis et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2001). Knockout of the UCP2 gene in the ob/ob mouse background, improved GSIS and reduced blood glucose (Zhang et al., 2001).

In C57Bl6 mice, reported by some groups to exhibit impaired insulin secretion relative to other strains (Toye et al., 2005), mutations in the Nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (Nnt) have been identified. Nnt is a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein catalyzing reversible reduction of NADP+ by NADH, promoting proton translocation across the membrane and detoxification of ROS (Arkblad et al., 2005; Hoek and Rydstrom, 1988). Accumulation of ROS in the mitochondrial matrix can increase UCP2 activity, enhancing proton leakage and impairing ATP production (Echtay et al., 2002; Krauss et al., 2003). Nnt–transgenic mice showed impaired glucose tolerance and loss of both β-cell ATP synthesis and GSIS, consistent with a direct effect of impaired ATP production on KATP channel activity (Freeman et al., 2006). No mutations in mitochondrial enzymes have been reported in human diabetes, but a few mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) have. Mitochondria are a major source of free radicals, as a result of electrons leaking into the mitochondrial matrix reacting with molecular oxygen. An A3243G mutation in the tRNA(Leu(UUR)) gene was identified as a common diabetes-causing mitochondrial DNA mutation, mutation carriers exhibiting reduced first- and second-phase insulin secretion (Maassen et al., 2004), although the underlying molecular mechanisms are unclear. A mouse model of mitochondrial diabetes was generated by disruption of the nuclear gene Tfam, a transcriptional activator essential for mtDNA expression in β-cells (Silva et al., 2000). These mice showed depletion of mtDNA and developed diabetes at 5 weeks. Again, consistent with impaired M-E coupling, dispersed β-cells demonstrated hyperpolarized mitochondria, impaired Ca2+-signaling, and decreased GSIS. As in other models in which the primary defect is in M-E coupling, older Tfam-mutant mice showed reduced β-cell mass, indicating secondary progression (Silva et al., 2000). Recently, a transgenic mouse expressing mutant mtDNA polymerase γ (D181A polyγ) under insulin promoter-control was generated (Bensch et al., 2009), to cause accumulation of mtDNA mutations in β-cells. Despite males being overtly diabetic and females being glucose-intolerant by 6 weeks of age, GSIS was normal in isolated islets, suggesting a non-islet mechanism.

Oxygen-sensing pathways have also been implicated in modulation of insulin secretion: both β-cell specific (βVhlKO) and whole pancreas (VhlKO) knockout of von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein, which controls the degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), are glucose intolerant. Isolated islets show altered expression of β-cell glucose transporter and glycolytic genes, impaired glucose uptake and metabolism, and reduced GSIS (Cantley et al., 2009; Zehetner et al., 2008). Hif1α is expressed in these β-cells, and deletion of Hif1α restores GSIS in these mice (Cantley et al., 2009; Zehetner et al., 2008). Beta-cell specific Vhl-deficient mice hypersecrete insulin at low glucose concentration, but have impaired GSIS and increased [Ca2+]i (Cantley et al., 2009; Zehetner et al., 2008). Thus, impaired mitochondrial oxidation and/or oxygen-sensing mechanisms may all contribute to altered secretion via altered M-E coupling.

3. Genetic manipulation of KATP channels: mouse models of hyperinsulinism and diabetes

KATP Knockout and dominant-negative mice as models of hyperinsulinemia

Beta-cell KATP channels are complexes of the sulfonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1, ABCC8) and the potassium channel Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) (Clement et al., 1997; Inagaki et al., 1995; Sakura et al., 1995; Shyng and Nichols, 1997) In humans, LOF mutations in these genes are major causes of HI (Aguilar-Bryan et al., 2001; Dunne et al., 2004; Huopio et al., 2002a; Stanley, 2002). Reduction of channel expression at the cell surface, loss of MgADP-stimulation, or abolished channel activity are primary defects (Dunne et al., 1997; Nestorowicz et al., 1998; Nichols et al., 1996; Shyng et al., 1998). Kir6.2−/− and SUR1−/− mice (Miki et al., 1998; Seghers et al., 2000; Shiota et al., 2002), as well as mice expressing a dominant-negative Kir6.2 mutant transgene in β-cells (Kir6.2[AAA] (Koster et al., 2002) or Kir6.2[G132S] (Miki et al., 1997), both of which disrupt the selectivity filter) have been generated. Kir6.2−/− and SUR1−/− mice (Miki et al., 1998; Seghers et al., 2000; Shiota et al., 2002), lacking KATP in multiple tissues, and Kir6.2[G132S] mice which specifically lack β-cell KATP (Miki et al., 1997), show a complex and surprising phenotype that does not trivially replicate human HI. These mice reportedly demonstrate transient hyperinsulinemia and hypoglycemia as neonates, but islets from adult SUR1−/− or Kir6.2−/− mice show a dramatic loss of insulin secretion at all glucose concentration, and the animals are relatively hypoinsulinemic (Miki et al., 1998; Seghers et al., 2000; Shiota et al., 2002). In Kir6.2[G132S] mice, loss of β-cell mass was reported (Miki et al., 1997), although hyperglycemia was apparently spontaneously improved and insulin content even increased in older mice (Oyama et al., 2006).

Conversely, β-cell specific Kir6.2[AAA] dominant-negative mice, which lose KATP channel activity in only ~70% β-cells, exhibit elevated circulating insulin levels that persists through adulthood, with essentially normal insulin content and islet morphology (Koster et al., 2002). Heterozygous Kir6.2+/− and SUR1+/− mice, with ~60% reduction in KATP density in every cell, show a similar phenotype (Remedi et al., 2006). Thus, while heterozygous Kir6.2+/− and SUR1+/− mice, as well as Kir6.2[AAA] mice all show enhanced glucose-tolerance and increased GSIS (Remedi et al., 2006), Kir6.2−/− and SUR−/− mice (100% reduction in KATP density) are glucose-intolerant. Complete lack of KATP activity has been reported in β-cells from some HI patients (Kane et al., 1996). However, the phenotype of many HI mutations would suggest that KATP is not always completely absent (de Lonlay et al., 2002; Huopio et al., 2002a; Huopio et al., 2002b; Shyng et al., 1998), and active KATP channels and diazoxide sensitivity have been detected in some patients (Henwood et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2006). The progress of the disease can be complex and, although surgical removal of excess pancreatic tissue may result in diabetes, it is also observed that some non-surgically treated patients spontaneously cross-over to diabetes (Grimberg et al., 2001; Huopio et al., 2002a; Leibowitz et al., 1995). Apparent recapitulation of this complex phenotype in mice with variable loss of KATP channels suggests that similar mechanism may be operating in mice and humans.

Overactive β-cell KATP channel in mice cause Neonatal Diabetes

GOF KATP channel mutations resulting in ‘overactive’ β-cell channels are expected to decrease excitability and suppress GSIS. Mice expressing mutant KATP channels with reduced ATP-sensitivity only in pancreatic β-cells (Kir6.2[ΔN2-30]) developed severe NDM and died within days of birth (Koster et al., 2000), predicting the subsequent demonstration that GOF mutations in Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and SUR1 (ABCC8) are common causes of human TNDM and PNDM (Gloyn et al., 2004; Hattersley and Ashcroft, 2005). These mutations reduce sensitivity to ATP inhibition, by decreasing the affinity of the ATP-binding pocket for the nucleotide, or by allosterically decreasing ATP-affinity (Ashcroft, 2006; Nichols, 2006). Recently, inducible KATP GOF transgenic mice under Cre-recombinase control have been generated (Girard et al., 2009; Remedi et al., 2009). Both rat insulin promoter (Rip-Cre)- (Herrera, 2002) and tamoxifen-inducible Pdx1PBCreERTM (Zhang et al., 2005) (Pdx-Cre)-driven transgenes lead to severe glucose-intolerance, around weaning (Rip-Cre), or within two weeks after tamoxifen injection (Pdx-Cre), and progress to severe diabetes (Girard et al., 2009; Remedi et al., 2009). They also show growth retardation and dramatic reduction of insulin content, accompanied by profound loss of β-cell mass over time (Remedi et al., 2009). Importantly, syngeneic islet transplantation or chronic treatment with glibenclamide, initiated prior to tamoxifen induction, not only prevented the development of diabetes, but also maintained both pancreatic islet architecture and β-cell mass (Remedi et al., 2009).

Control-based genetic studies (Gloyn, 2003), metanalysis (Nielsen et al., 2003; Schwanstecher et al., 2002) and GWAS (Saxena et al., 2007; Zeggini et al., 2007) have established the E23K polymorphism in Kir6.2 as a risk factor in type-2 diabetes. Although early studies failed to demonstrate significant effect of E23K on recombinant KATP channel properties (Riedel et al., 2003; Sakura et al., 1996), subsequent studies reveal a small rightward shift in ATP sensitivity (Schwanstecher et al., 2002; Villareal et al., 2009). Such GOF behavior is predicted to suppress GSIS, consistent with the findings in non-diabetic individuals who carry this polymorphism (Chistiakov et al., 2009; Florez et al., 2004; Nielsen et al., 2003; Villareal et al., 2009). In addition to severely diabetic transgenic mice (Koster et al., 2000), additional KATP GOF (Kir6.2[ΔN2-30]) transgenic mouse lines with lower levels of transgene expression, exhibit normal islet morphology and insulin content, but are glucose-intolerant (and more so on high fat diet) (Koster et al., 2006), reiterating the general phenotype of humans carrying the E23K polymorphism (Villareal et al., 2009).

4. Mouse models of altered Ca channels

The role of L-type high voltage-activated Ca channels in hyperisulinemia and diabetes

The Cav1 sub-family, comprising 4 members (Cav1.1 to Cav1.4) (Hofmann et al., 1999), generates L-type voltage-dependent Ca channels (VDCCs) involved in insulin secretion (Ichii et al., 2005; Mears, 2004; Yang and Berggren, 2005a, b). Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 may be the dominant subunits (Barg et al., 2001; Iwashima et al., 1993; Yang et al., 1999) (Fig. 1). Cav1.3−/− mice are viable with no major disturbances in insulin secretion, even though they show deafness, bradycardia and arrhythmias (Platzer et al., 2000), suggesting that Cav1.3 is not normally a major player in mouse β-cell insulin secretion. Cav1.2−/− mice die in utero before day 15, presumably because of lack of functional VDCC in the heart (Seisenberger et al., 2000), obviating study of β-cell roles, but β-cell specific knockout (β-Cav1.2−/−) mice (deleted exons in one allele of Cav1.2 and ‘floxed’ exons in the other, using Cre/loxP recombination), exhibit decreased VDCC, and a marked reduction in insulin exocytosis in response to initial membrane depolarization (first-phase) but unaffected second-phase secretion (Schulla et al., 2003). The β-cell Cav1.2 is sensitive to dihydropyridines (DHPs), and these drugs almost abolish GSIS in β-cell lines (Minami et al., 2002). Cav1.2−/− β-cells show no DHP-sensitive VDCC, but glucose-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations and AP firing persist, suggesting that L-type channels are necessary for insulin secretion but not for electrical activity and [Ca2+]i oscillations, perhaps indicating compensatory overexpression of non-L-type channels in β-cells lacking Cav1.2 (Schulla et al., 2003). Timothy syndrome, due to Cav1.2 overactivity, is characterized by deafness, webbing of fingers and toes, congenital heart disease and severe arrhythmias, and is associated with hypoglycemia (Splawski et al., 2004), probably due to Cav1.2 overactivity in β-cells. It seems likely that LOF polymorphisms or mutations of L-type VDCC in humans should be associated with diabetic syndromes, but none have yet been identified, and we speculate that this is again because of compensatory upregulation of other subunits.

Non L-type high voltage-activated Ca channels in the regulation of insulin secretion

The role of non-L-type, high voltage-activated, Ca channels (e.g. Cav2.3 R-type Ca channel) in β-cells is controversial, and some studies indicate their absence in human islets (Braun et al., 2008; Yang and Berggren, 2005b), but there is evidence for association of Cav2.3 polymorphisms with impaired insulin secretion and development of type-2 diabetes (Holmkvist et al., 2007). They appear to play a role in second-phase insulin secretion by mobilizing insulin reserve granules to the readily releasable pool in mice. Cav2.3 (CACNA1E) knockout (Cav2.3−/−) mice show impaired glucose tolerance and GSIS (Pereverzev et al., 2002). In addition, genetic, or pharmacological (using R-type channel blocker SNX482) ablation of Cav2.3 channels strongly suppresses second-phase secretion, but the first-phase is unaltered (Jing et al., 2005). Pancreatic cells from Cav2.3−/− mice show reduction of Ca2+ signaling and impairment of insulin granule recruitment after the initial exocytotic burst (Jing et al., 2005).

5. Voltage-dependent outward K+ current: repolarization of β-cells and insulin secretion

Pancreatic β-cells have prominent voltage dependent outward K+ (Kv) currents that mediate AP repolarization (Dukes and Philipson, 1996; Philipson, 1999; Rorsman and Trube, 1986; Su et al., 2001), and both Kv1 (KCNA) and Kv2 (KCNB) channel families are involved (MacDonald et al., 2001) (Fig. 1C). Kv2.1 expression is high in β-cells (MacDonald et al., 2001; Roe et al., 1996), and adenovirus-mediated expression of dominant-negative Kv2.1 reduced (60-70%) β-cell delayed-rectifier currents and markedly enhanced GSIS (MacDonald et al., 2001). Perfusion of mouse pancreas with Kv2.1 antagonists enhances first- and second-phase insulin secretion, but, as expected, does not affect basal insulin levels (MacDonald et al., 2002). Philipson and colleagues (Philipson et al., 1994) generated Kv2.1-overexpressing transgenic mice under Rip control. Although expression levels were variable, the mice showed hyperglycemia and hypoinsulinemia, with normal β-cell morphology and insulin content (Philipson et al., 1994). Conversely, Kv2.1 knockout (Kv2.1−/−) mice show reduced fasting blood glucose level and elevated serum insulin (Jacobson et al., 2007), with enhanced GSIS. Isolated Kv2.1−/− β-cells exhibit increased glucose-induced AP duration but firing frequency is diminished (Jacobson et al., 2007), consistent with loss of Kv currents, and enhanced Ca2+ entry during the AP, leading to increased insulin secretion. SNARE proteins also affect insulin exocytosis (Daniel et al., 1999). Syntaxin-1A (STX-1A) directly binds and regulates Ca2+ channels (Yang et al., 1999), KATP (Kang et al., 2002) and Kv2.1 channels in β-cells (Leung et al., 2003; Leung et al., 2005). Transgenic mice overexpressing STX-1A in β-cells demonstrate fasting hyperglycemia and reduced plasma insulin (Lam et al., 2005), with reduced Cav currents but little change in the Kv and KATP currents (Lam et al., 2005).

Multiple other K channels may be involved in insulin secretion and may ultimately be shown to be involved in secretion defects. Variants in the voltage-gated potassium channel KCNQ1 gene have recently been associated with susceptibility to type-2 diabetes, impaired fasting glucose and β-cell function, in various populations (Hu et al., 2009; Tan et al., 2009; Unoki et al., 2008; Yasuda et al., 2008). The evidence that KCNQ1 locus harbors control elements that influence the imprinting of neighboring genes (Lee et al., 1997; Smilinich et al., 1999), some associated with type-2 diabetes, suggest that the mechanism responsible for type-2 diabetes susceptibility may extend beyond the direct effect of KCNQ1 (McCarthy, 2008). KCNQ1−/− mice demonstrate enhanced insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance, as well as decreased fed and fasting glucose and insulin levels (Boini et al., 2009), broadly consistent with a role in secretion, but the evidence for KCNQ1 expression in islets is weak (Jonsson et al., 2009; Mussig et al., 2009; Stancakova et al., 2009), and further investigation is needed. The role of Ca-activated potassium channels in β-cell function remains controversial. Early studies demonstrated the presence of Ca2+-dependent K+ conductances in β-cells (Atwater et al., 1983) and recent studies have argued for roles of small-conductance SK channels in rodent β-cells (Tamarina et al., 2003), and large-conductance BK channels may be prominent in human β-cells (Braun et al., 2008), but again, more studies are clearly needed.

6. Genetic alterations of Calmodulin in hyperglycemia and neonatal diabetes

Calmodulin and protein kinase C are two β-cell calcium-binding proteins with multiple potential roles in secretion (Hubinont et al., 1984; Prentki and Matschinsky, 1987; Sugden et al., 1979). Calmodulin may be a major calcium buffer, and transgenic mice that overexpress calmodulin (CaM) specifically in pancreatic β-cells develop severe diabetes within hours after birth, demonstrating elevated blood glucose and glucagon levels, and a marked reduction in insulin levels (Epstein et al., 1992b), very much like that seen in GOF Kir6.2 transgenic mice (Remedi et al., 2009). A similar phenotype was found in transgenic mice overexpressing inactive CaM-8, containing a deletion of 8 amino acids in the central helix (Ribar et al., 1995), suggesting a mechanism involving Ca2+ buffering rather than downstream calmodulin signaling; and consistent with Ca2+-sensitive pools of insulin granules: vesicles colocalized with VDCC (Pertusa et al., 1999).

7. Integrating the models: emerging themes and future directions

M-E coupling leads to Ca2+: So what?

In a 2002 review, we systematically compared the phenotypic consequences of transgenic manipulation of multiple genes in pancreatic β-cells (Nichols and Koster, 2002). Although genes obviously involved in pancreatic development lead to loss of β-cells and inevitably insulin-dependent diabetes, many signaling molecules have relatively mild consequences, except for those involved directly in coupling glucose uptake, through metabolism, to electrical signaling (e.g. GLUT2, GCK, Kir6.2, SUR1). In these cases, even minor over- or underactivity leads to under- or oversecretion, and marked hyperinsulinism or diabetes. This is dramatic in the case of KATP (where even relatively small shifts in the ATP sensitivity leads severe diabetes, (Girard et al., 2009; Koster et al., 2000; Remedi et al., 2009), glucokinase knockout (Grupe et al., 1995; Terauchi et al., 1995), or calmodulin overexpression (Epstein et al., 1992b; Ribar et al., 1995). The data from human NDM patients is entirely consistent: monogenic NDM is caused by loss of glucokinase and by GOF mutations in KATP (Gloyn et al., 2003; Gloyn et al., 2004). In the latter case, the more severe the ATP-insensitivity, the more severe the disease, but even mild shifts in ATP-sensitivity can cause neonatal disease (Hattersley and Ashcroft, 2005; Sivaprasadarao et al., 2007).

The reiteration of very similar phenotype for mutations in these 3 genes seems quite telling: at least at early stages of life, the pathway from glucose metabolism, initiated by glucokinase activity, through excitability to elevated [Ca2+]i is critical, and cannot be compromised. The calmodulin-overactive mouse is interesting in this regard. Early studies indicated that the primary defect is probably the consequent increase in Ca2+ buffering, leading to depressed [Ca2+]i, since the phenotype is the same when an inactive mutant is overexpressed (Easom, 1999; Epstein et al., 1992b; Ribar et al., 1995), indicating that failure of [Ca2+]i elevation is causal.

So what are the broader implications for β-cell function and diabetes? Sulfonylureas are effective treatments for NDM due to KATP mutations (Hattersley and Ashcroft, 2005; Pearson et al., 2006; Wambach et al., 2009), providing generally better control of blood glucose than insulin, and potentially without the long-term failure found in type-2 patients (Rustenbeck, 2002). Total loss of mouse β-cell GCK (i.e. a more severe defect than likely present in most human LOF mutations (Njolstad et al., 2001); (Njolstad et al., 2003; Porter et al., 2005) results in failure to close KATP channels (Sakura et al., 1998) and consequent diabetes is at least partially abrogated by removal of KATP channels in GK−/−/Kir6.2−/− double knockout mice (Remedi et al., 2005). This suggests that GCK underactivity, and potentially any other defects upstream of KATP, i.e. between glucose uptake and KATP closure might be treatable at the level of the KATP channel, and it is interesting that a recent report (Turkkahraman et al., 2008) indeed suggests that such treatment may be effective in GCK-dependent human NDM.

Secondary consequences of altered M-E coupling

As discussed above, it is clear from studies of calmodulin overexpressors (Epstein et al., 1992b; Ribar et al., 1995), GCK knockouts (Grupe et al., 1995; Terauchi et al., 1995) and from KATP GOF mice (Koster et al., 2000; Remedi et al., 2009), that diabetes can result simply from loss of insulin secretion due to failure of M-E coupling. At the earliest stages of the disease (Koster et al., 2000; Remedi et al., 2009), and chronically when protected against the systemic consequences (Remedi et al., 2009), β-cells do not deteriorate, and maintain normal insulin content, even though secretion in response to glucose remains refractory. However, in the untreated situation there is rapid deterioration: β-cell mass is lost, and insulin content disappears (Girard et al., 2009; Koster et al., 2000; Remedi et al., 2009). These models therefore provide important tools to understand the basis of this secondary failure. There are many hypotheses behind the ‘glucotoxic’ death of β-cells in diabetes (Poitout and Robertson, 2008). It is clear that in some animal models it can result from ‘overstimulation’ by glucose (Grill and Bjorklund, 2001) and, since this can be protected against by infusion of diazoxide (Guldstrand et al., 2002; Sako and Grill, 1990), implicitly involves hyper-activation of Ca2+ stimulation. (Grill and Bjorklund, 2001) examined long-term effects of diazoxide treatment on β-cell function in islets transplanted from normal rats into syngeneic recipients previously made diabetic by streptozotocin (Hiramatsu et al., 2000). After 8 weeks transplant, function was improved, implying a protection against ‘overstimulation’, and consequent ‘Ca2+ toxicity’ (which could lead to multiple pathways of cell death, including Ca-dependent proteases and apoptosis). Such a mechanism may well occur in otherwise normal islets facing an abnormal ‘glucose load’, but in the case of reduced signaling through M-E coupling, this does not seem possible, since even in late stages of disease, islets remain refractory to stimulation and intracellular [Ca2+] remains low (Girard et al., 2009; Remedi et al., 2009). Potential mechanisms of ‘glucotoxicity’ without ‘Ca2+ toxicity’ are manifold, including the generation of advanced glycosylation end products (AGE) and other potentially toxic compounds (Del Prato et al., 2007; Grill and Bjorklund, 2001; Zhao et al., 2009), and the islets from these animals will therefore provide models for future studies of the mechanisms of ‘glucotoxic’ loss of β-cells and insulin content, in the face of low intracellular [Ca2+].

M-E coupling leads to Ca2+: Surprises too

A clear picture emerging from animal models is that reduced M-E coupling leads to reduced [Ca2+]i, and reduced insulin secretion, with remarkably small tolerance limits, and this is borne out in humans by the finding that NDM results from relatively small changes in ATP-sensitivity of the KATP channel. But there are surprises on the other side of the ‘see-saw’. The lack of hyperinsulinism (in fact relative hypoinsulinism) in mice completely lacking KATP channels is not readily explained (Dufer et al., 2004). Our studies have demonstrated that partial loss of KATP has the expected effect of shifting secretion to lower glucose levels, leading to enhanced glucose tolerance, but below a certain level (<~15% of normal KATP) (Nichols et al., 2007; Remedi et al., 2006), there is crossover to marked undersecretion, due to downregulation of secretion itself, in the face of a maintained elevated [Ca2+]i. While this might be ascribed to some form of ‘Ca2+ toxicity’, it appears to be very labile, and readily reversible: the phenotype is closely replicated by chronic pharmacological block of channel activity in mice implanted with slow-release high-dose glibenclamide pellets, yet this phenotype is completely reversed within hours of removal of the drug (Remedi and Nichols, 2008). Again, such findings point to previously unconsidered mechanisms, and may be of relevance to humans. Firstly, as discussed, there are reports that HI patients with LOF KATP mutations can cross over to a glucose-intolerant phenotype later in life, even without pancreatectomy (de Lonlay et al., 2002; Dunne et al., 2004; Mazor-Aronovitch et al., 2009). Secondly, chronic sulfonylurea treatment inevitably fails in type-2 patients, again potentially involving chronic downregulation of secretion that can be reversed by β-cell ‘rest’ (Guldstrand et al., 2002; Pfutzner et al., 2006; Sargsyan et al., 2008).

Concluding remarks

Clearly mice and humans are not genetically the same, and differential islet morphology is a relevant issue. We do not suggest that animal models can supplant clinical experience, or that the implications from animal models can automatically translate to clinical relevance. However, many major players in M-E coupling are likely to be the same in humans and mouse, and recent studies show marked parallels in disease etiology and progression resulting from their derangement in mouse and man. Given the undisputed experimental advantages of the mouse, both genetically and physiologically, mouse models will continue to provide important avenues for explaining basic mechanisms of M-E coupling, but also the molecular basis of, and therapeutic possibilities for treating, diseases that results from its derangement.

Acknowledgements

Our own experimental work has been supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK69445 (to CGN). We are additionally grateful to the Washington University DRTC (DK20579) for reagent support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Nakazaki M. Of mice and men: K(ATP) channels and insulin secretion. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2001;56:47–68. doi: 10.1210/rp.56.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki E, Lipes MA, Patti ME, Bruning JC, Haag B, 3rd, Johnson RS, Kahn CR. Alternative pathway of insulin signalling in mice with targeted disruption of the IRS-1 gene. Nature. 1994;372:186–190. doi: 10.1038/372186a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkblad EL, Tuck S, Pestov NB, Dmitriev RI, Kostina MB, Stenvall J, Tranberg M, Rydstrom J. A Caenorhabditis elegans mutant lacking functional nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase displays increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2005;38:1518–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenijevic D. Disruption of the uncoupling protein-2 gene in mice reveals a role in immunity and reactive oxygen species production.[see comment] Nat Genet. 2000;26:435–439. doi: 10.1038/82565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM. From molecule to malady. Nature. 2006;440:440–447. doi: 10.1038/nature04707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. ATP-sensitive K+ channels: a link between B-cell metabolism and insulin secretion. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990;18:109–111. doi: 10.1042/bst0180109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwater I, Rosario L, Rojas E. Properties of the Ca-activated K+ channel in pancreatic beta-cells. Cell Calcium. 1983;4:451–461. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(83)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aynsley-Green A. Nesidioblastosis of the pancreas in infancy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 1981;23:372–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bali D, Svetlanov A, Lee HW, Fusco-DeMane D, Leiser M, Li B, Barzilai N, Surana M, Hou H, Fleischer N. Animal model for maturity-onset diabetes of the young generated by disruption of the mouse glucokinase gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:21464–21467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barg S, Ma X, Eliasson L, Galvanovskis J, Gopel SO, Obermuller S, Platzer J, Renstrom E, Trus M, Atlas D, Striessnig J, Rorsman P. Fast exocytosis with few Ca(2+) channels in insulin-secreting mouse pancreatic B cells. Biophysical Journal. 2001;81:3308–3323. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75964-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensch KG, Mott JL, Chang SW, Hansen PA, Moxley MA, Chambers KT, de Graaf W, Zassenhaus HP, Corbett JA. Selective mtDNA mutation accumulation results in beta-cell apoptosis and diabetes development. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E672–680. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90839.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boini KM, Graf D, Hennige AM, Koka S, Kempe DS, Wang K, Ackermann TF, Foller M, Vallon V, Pfeifer K, Schleicher E, Ullrich S, Haring HU, Haussinger D, Lang F. Enhanced insulin sensitivity of gene-targeted mice lacking functional KCNQ1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1695–1701. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90839.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M, Ramracheya R, Bengtsson M, Zhang Q, Karanauskaite J, Partridge C, Johnson PR, Rorsman P. Voltage-gated ion channels in human pancreatic beta-cells: electrophysiological characterization and role in insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2008;57:1618–1628. doi: 10.2337/db07-0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briaud I, Kelpe CL, Johnson LM, Tran PO, Poitout V. Differential effects of hyperlipidemia on insulin secretion in islets of langerhans from hyperglycemic versus normoglycemic rats. Diabetes. 2002;51:662–668. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.3.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley J, Selman C, Shukla D, Abramov AY, Forstreuter F, Esteban MA, Claret M, Lingard SJ, Clements M, Harten SK, Asare-Anane H, Batterham RL, Herrera PL, Persaud SJ, Duchen MR, Maxwell PH, Withers DJ. Deletion of the von Hippel-Lindau gene in pancreatic beta cells impairs glucose homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:125–135. doi: 10.1172/JCI26934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauchi S, Meyre D, Durand E, Proenca C, Marre M, Hadjadj S, Choquet H, De Graeve F, Gaget S, Allegaert F, Delplanque J, Permutt MA, Wasson J, Blech I, Charpentier G, Balkau B, Vergnaud AC, Czernichow S, Patsch W, Chikri M, Glaser B, Sladek R, Froguel P. Post genome-wide association studies of novel genes associated with type 2 diabetes show gene-gene interaction and high predictive value. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CB, De Leo D, Joseph JW, McQuaid TS, Ha XF, Xu F, Tsushima RG, Pennefather PS, Salapatek AM, Wheeler MB. Increased uncoupling protein-2 levels in beta-cells are associated with impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion: mechanism of action. Diabetes. 2001;50:1302–1310. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CB, MacDonald PE, Saleh MC, Johns DC, Marban E, Wheeler MB. Overexpression of uncoupling protein 2 inhibits glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from rat islets. Diabetes. 1999;48:1482–1486. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.7.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chistiakov DA, Potapov VA, Khodirev DC, Shamkhalova MS, Shestakova MV, Nosikov VV. Genetic variations in the pancreatic ATP-sensitive potassium channel, beta-cell dysfunction, and susceptibility to type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2009;46:43–49. doi: 10.1007/s00592-008-0056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement J.P.t., Kunjilwar K, Gonzalez G, Schwanstecher M, Panten U, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Association and stoichiometry of K(ATP) channel subunits. Neuron. 1997;18:827–838. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codner E, Deng L, Perez-Bravo F, Roman R, Lanzano P, Cassorla F, Chung WK. Glucokinase mutations in young children with hyperglycemia. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2006;22:348–355. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta-Munoz AL, Huopio H, Otonkoski T, Gomez-Zumaquero JM, Nanto-Salonen K, Rahier J, Lopez-Enriquez S, Garcia-Gimeno MA, Sanz P, Soriguer FC, Laakso M. Severe persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia due to a de novo glucokinase mutation. Diabetes. 2004;53:2164–2168. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel S, Noda M, Straub SG, Sharp GW. Identification of the docked granule pool responsible for the first phase of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 1999;48:1686–1690. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.9.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lonlay P, Fournet JC, Touati G, Groos MS, Martin D, Sevin C, Delagne V, Mayaud C, Chigot V, Sempoux C, Brusset MC, Laborde K, Bellane-Chantelot C, Vassault A, Rahier J, Junien C, Brunelle F, Nihoul-Fekete C, Saudubray JM, Robert JJ. Heterogeneity of persistent hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia. A series of 175 cases. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161:37–48. doi: 10.1007/s004310100847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prato S, Bianchi C, Marchetti P. beta-cell function and antidiabetic pharmacotherapy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007;23:518–527. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufer M, Haspel D, Krippeit-Drews P, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Drews G. Oscillations of membrane potential and cytosolic Ca(2+) concentration in SUR1(-/-) beta cells. Diabetologia. 2004;47:488–498. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukes ID, Philipson LH. K+ channels: generating excitement in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 1996;45:845–853. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.7.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne MJ, Cosgrove KE, Shepherd RM, Aynley-Green A, Lindley KJ. Hyperinsulinism in Infancy: From Basic Science to Clinical Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:239–275. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne MJ, Kane C, Shepherd RM, Sanchez JA, James RF, Johnson PR, Aynsley-Green A, Lu S, Clement J.P.t., Lindley KJ, Seino S, Aguilar-Bryan L. Familial persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy and mutations in the sulfonylurea receptor. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336:703–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703063361005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easom RA. CaM kinase II: a protein kinase with extraordinary talents germane to insulin exocytosis. Diabetes. 1999;48:675–684. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.4.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echtay KS, Roussel D, St-Pierre J, Jekabsons MB, Cadenas S, Stuart JA, Harper JA, Roebuck SJ, Morrison A, Pickering S, Clapham JC, Brand MD. Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Nature. 2002;415:96–99. doi: 10.1038/415096a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efrat S, Tal M, Lodish HF. The pancreatic beta-cell glucose sensor. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:535–538. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein PN, Boschero AC, Atwater I, Cai X, Overbeek PA. Expression of yeast hexokinase in pancreatic beta cells of transgenic mice reduces blood glucose, enhances insulin secretion, and decreases diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992a;89:12038–12042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein PN, Ribar TJ, Decker GL, Yaney G, Means AR. Elevated beta-cell calmodulin produces a unique insulin secretory defect in transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 1992b;130:1387–1393. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.3.1371447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erecinska M, Bryla J, Michalik M, Meglasson MD, Nelson D. Energy metabolism in islets of Langerhans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1101:273–295. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(92)90084-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajans SS, Bell GI, Polonsky KS. Molecular mechanisms and clinical pathophysiology of maturity-onset diabetes of the young. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:971–980. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florez JC, Burtt N, de Bakker PI, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Holmkvist J, Gaudet D, Hudson TJ, Schaffner SF, Daly MJ, Hirschhorn JN, Groop L, Altshuler D. Haplotype structure and genotype-phenotype correlations of the sulfonylurea receptor and the islet ATP-sensitive potassium channel gene region. Diabetes. 2004;53:1360–1368. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H, Shimomura K, Cox RD, Ashcroft FM. Nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase: a link between insulin secretion, glucose metabolism and oxidative stress. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:806–810. doi: 10.1042/BST0340806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard CA, Wunderlich FT, Shimomura K, Collins S, Kaizik S, Proks P, Abdulkader F, Clark A, Ball V, Zubcevic L, Bentley L, Clark R, Church C, Hugill A, Galvanovskis J, Cox R, Rorsman P, Bruning JC, Ashcroft FM. Expression of an activating mutation in the gene encoding the KATP channel subunit Kir6.2 in mouse pancreatic beta cells recapitulates neonatal diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:80–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI35772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloyn AL. The search for type 2 diabetes genes. Ageing Res Rev. 2003;2:111–127. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloyn AL, Colclough K, Batten M, Allen LI, Beards F, Hattersley AT, Ellard S. Glucokinase (GCK) mutations in hyper- and hypoglycemia: maturity-onset diabetes of the young, permanent neonatal diabetes, and hyperinsulinemia of infancy. Human Mutation. 2003;22:417. doi: 10.1002/humu.9186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloyn AL, Ellard S, Shield JP, Temple IK, Mackay DJ, Polak M, Barrett T, Hattersley AT. Complete glucokinase deficiency is not a common cause of permanent neonatal diabetes. Diabetologia. 2002;45:290. doi: 10.1007/s00125-001-0746-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloyn AL, Pearson ER, Antcliff JF, Proks P, Bruining GJ, Slingerland AS, Howard N, Srinivasan S, Silva JMCL, Molnes J, Edghill EL, Frayling TM, Temple IK, Mackay D, Shield JPH, Sumnik Z, van Rhijn A, Wales JKH, Clark P, Gorman S, Aisenberg J, Ellard S, Njolstad PR, Ashcroft FM, Hattersley AT. Activating Mutations in the Gene Encoding the ATP-Sensitive Potassium-Channel Subunit Kir6.2 and Permanent Neonatal Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350:1838–1849. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill V, Bjorklund A. Overstimulation and beta-cell function. Diabetes. 2001;50(Suppl 1):S122–124. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2007.s122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimberg A, Ferry RJ, Jr., Kelly A, Koo-McCoy S, Polonsky K, Glaser B, Permutt MA, Aguilar-Bryan L, Stafford D, Thornton PS, Baker L, Stanley CA. Dysregulation of insulin secretion in children with congenital hyperinsulinism due to sulfonylurea receptor mutations. Diabetes. 2001;50:322–328. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupe A, Hultgren B, Ryan A, Ma YH, Bauer M, Stewart TA. Transgenic knockouts reveal a critical requirement for pancreatic beta cell glucokinase in maintaining glucose homeostasis. Cell. 1995;83:69–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90235-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillam MT, Dupraz P, Thorens B. Glucose uptake, utilization, and signaling in GLUT2-null islets. Diabetes. 2000;49:1485–1491. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillam MT, Hummler E, Schaerer E, Yeh JI, Birnbaum MJ, Beermann F, Schmidt A, Deriaz N, Thorens B, Wu JY. Early diabetes and abnormal postnatal pancreatic islet development in mice lacking Glut-2. Nat Genet. 1997;17:327–330. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillausseau PJ, Meas T, Virally M, Laloi-Michelin M, Medeau V, Kevorkian JP. Abnormalities in insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2008;34(Suppl 2):S43–48. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(08)73394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldstrand M, Grill V, Bjorklund A, Lins PE, Adamson U. Improved beta cell function after short-term treatment with diazoxide in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2002;28:448–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattersley AT, Ashcroft FM. Activating mutations in Kir6.2 and neonatal diabetes: new clinical syndromes, new scientific insights, and new therapy. Diabetes. 2005;54:2503–2513. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henwood MJ, Kelly A, MacMullen C, Bhatia P, Ganguly A, Thornton PS, Stanley CA. Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in Children with Congenital Hyperinsulinism Due to Recessive Mutations of the Adenosine Triphosphate-Sensitive Potassium Channel Genes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:789–794. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera PL. Defining the cell lineages of the islets of Langerhans using transgenic mice. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2002;46:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himms-Hagen J, Harper ME. Physiological role of UCP3 may be export of fatty acids from mitochondria when fatty acid oxidation predominates: an hypothesis. Experimental Biology & Medicine. 2001;226:78–84. doi: 10.1177/153537020122600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu S, Hoog A, Moller C, Grill V. Treatment with diazoxide causes prolonged improvement of beta-cell function in rat islets transplanted to a diabetic environment. Metabolism. 2000;49:657–661. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(00)80044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek JB, Rydstrom J. Physiological roles of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase. Biochemical Journal. 1988;254:1–10. doi: 10.1042/bj2540001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Illes P, Aktories K, Meyer DK. Voltage-dependent calcium channels: from structure to function. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;127:1060–1063. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmkvist J, Tojjar D, Almgren P, Lyssenko V, Lindgren CM, Isomaa B, Tuomi T, Berglund G, Renstrom E, Groop L. Polymorphisms in the gene encoding the voltage-dependent Ca(2+) channel Ca (V)2.3 (CACNA1E) are associated with type 2 diabetes and impaired insulin secretion. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2467–2475. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Wang C, Zhang R, Ma X, Wang J, Lu J, Qin W, Bao Y, Xiang K, Jia W. Variations in KCNQ1 are associated with type 2 diabetes and beta cell function in a Chinese population. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1322–1325. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubinont CJ, Best L, Sener A, Malaisse WJ. Activation of protein kinase C by a tumor-promoting phorbol ester in pancreatic islets. FEBS Letters. 1984;170:247–253. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)81322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huopio H, Shyng SL, Otonkoski T, Nichols CG. K(ATP) channels and insulin secretion disorders. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002a;283:E207–216. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00047.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huopio H, Vauhkonen I, Komulainen J, Niskanen L, Otonkoski T, Laakso M. Carriers of an inactivating beta-cell ATP-sensitive K(+) channel mutation have normal glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity and appropriate insulin secretion. Diabetes Care. 2002b;25:101–106. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichii H, Inverardi L, Pileggi A, Molano RD, Cabrera O, Caicedo A, Messinger S, Kuroda Y, Berggren PO, Ricordi C. A novel method for the assessment of cellular composition and beta-cell viability in human islet preparations. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1635–1645. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement J.P.t., Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science. 1995;270:1166–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwashima Y, Pugh W, Depaoli AM, Takeda J, Seino S, Bell GI, Polonsky KS. Expression of calcium channel mRNAs in rat pancreatic islets and downregulation after glucose infusion. Diabetes. 1993;42:948–955. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.7.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson DA, Kuznetsov A, Lopez JP, Kash S, Ammala CE, Philipson LH. Kv2.1 ablation alters glucose-induced islet electrical activity, enhancing insulin secretion. Cell Metab. 2007;6:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing X, Li D, Olofsson CS, Salehi A, Surve VV, Caballero J, Ivarsson R, Lundquist I, Pereverzev A, Schneider T, Rorsman P, Renstrom E. CaV2.3 calcium channels control second-phase insulin release. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115:146–154. doi: 10.1172/JCI22518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson A, Isomaa B, Tuomi T, Taneera J, Salehi A, Nilsson P, Groop L, Lyssenko V. A variant in the KCNQ1 gene predicts future type 2 diabetes and mediates impaired insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2009;58:2409–2413. doi: 10.2337/db09-0246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph JW, Koshkin V, Zhang CY, Wang J, Lowell BB, Chan CB, Wheeler MB. Uncoupling protein 2 knockout mice have enhanced insulin secretory capacity after a high-fat diet. Diabetes. 2002;51:3211–3219. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.11.3211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane C, Shepherd RM, Squires PE, Johnson PR, James RF, Milla PJ, Aynsley-Green A, Lindley KJ, Dunne MJ. Loss of functional KATP channels in pancreatic beta-cells causes persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy.[comment] Nature Medicine. 1996;2:1344–1347. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Huang X, Pasyk EA, Ji J, Holz GG, Wheeler MB, Tsushima RG, Gaisano HY. Syntaxin-3 and syntaxin-1A inhibit L-type calcium channel activity, insulin biosynthesis and exocytosis in beta-cell lines. Diabetologia. 2002;45:231–241. doi: 10.1007/s00125-001-0718-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassis N, Bernard C, Pusterla A, Casteilla L, Penicaud L, Richard D, Ricquier D, Ktorza A. Correlation between pancreatic islet uncoupling protein-2 (UCP2) mRNA concentration and insulin status in rats. International Journal of Experimental Diabetes Research. 2000;1:185–193. doi: 10.1155/EDR.2000.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri H, Asano T, Ishihara H, Inukai K, Anai M, Miyazaki J, Tsukuda K, Kikuchi M, Yazaki Y, Oka Y. Nonsense mutation of glucokinase gene in late-onset non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1992;340:1316–1317. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92494-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster JC, Marshall BA, Ensor N, Corbett JA, Nichols CG. Targeted overactivity of beta cell K(ATP) channels induces profound neonatal diabetes. Cell. 2000;100:645–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster JC, Remedi MS, Flagg TP, Johnson JD, Markova KP, Marshall BA, Nichols CG. Hyperinsulinism induced by targeted suppression of beta cell KATP channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16992–16997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012479199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster JC, Remedi MS, Masia R, Patton B, Tong A, Nichols CG. Expression of ATP-insensitive KATP channels in pancreatic beta-cells underlies a spectrum of diabetic phenotypes. Diabetes. 2006;55:2957–2964. doi: 10.2337/db06-0732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss S, Zhang C-Y, Scorrano L, Dalgaard LT, St-Pierre J, Grey ST, Lowell BB. Superoxide-mediated activation of uncoupling protein 2 causes pancreatic {beta} cell dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;112:1831–1842. doi: 10.1172/JCI19774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam PP, Leung YM, Sheu L, Ellis J, Tsushima RG, Osborne LR, Gaisano HY. Transgenic mouse overexpressing syntaxin-1A as a diabetes model. Diabetes. 2005;54:2744–2754. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MP, Hu RJ, Johnson LA, Feinberg AP. Human KVLQT1 gene shows tissue-specific imprinting and encompasses Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Genet. 1997;15:181–185. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz G, Glaser B, Higazi AA, Salameh M, Cerasi E, Landau H. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy (nesidioblastosis) in clinical remission: high incidence of diabetes mellitus and persistent beta-cell dysfunction at long-term follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:386–392. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.2.7852494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung YM, Kang Y, Gao X, Xia F, Xie H, Sheu L, Tsuk S, Lotan I, Tsushima RG, Gaisano HY. Syntaxin 1A binds to the cytoplasmic C terminus of Kv2.1 to regulate channel gating and trafficking. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:17532–17538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung YM, Kang Y, Xia F, Sheu L, Gao X, Xie H, Tsushima RG, Gaisano HY. Open form of syntaxin-1A is a more potent inhibitor than wild-type syntaxin-1A of Kv2.1 channels. Biochemical Journal. 2005;387:195–202. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y-W, MacMullen C, Ganguly A, Stanley CA, Shyng S-L. A novel KCNJ11 mutation associated with congenital hyperinsulinism reduces the intrinsic open probability of beta-cell ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:3006–30012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511875200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maassen JA. Mitochondrial diabetes: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and genetic analysis. Am J Med Genet. 2002;115:66–70. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maassen JA, LM TH, Van Essen E, Heine RJ, Nijpels G, Tafrechi R.S. Jahangir, Raap AK, Janssen GM, Lemkes HH. Mitochondrial diabetes: molecular mechanisms and clinical presentation. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 1):S103–109. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald PE, Ha XF, Wang J, Smukler SR, Sun AM, Gaisano HY, Salapatek AM, Backx PH, Wheeler MB. Members of the Kv1 and Kv2 voltage-dependent K(+) channel families regulate insulin secretion. Molecular Endocrinology. 2001;15:1423–1435. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.8.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald PE, Joseph JW, Rorsman P. Glucose-sensing mechanisms in pancreatic beta-cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:2211–2225. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald PE, Sewing S, Wang J, Joseph JW, Smukler SR, Sakellaropoulos G, Saleh MC, Chan CB, Tsushima RG, Salapatek AM, Wheeler MB. Inhibition of Kv2.1 voltage-dependent K+ channels in pancreatic beta-cells enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:44938–44945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205532200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maechler P.a.W., C. B. Mitochondrial function in normal and diabetic beta-cells. Nature. 2001;414:807–812. doi: 10.1038/414807a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matschinsky FM. Banting Lecture 1995. A lesson in metabolic regulation inspired by the glucokinase glucose sensor paradigm. Diabetes. 1996;45:223–241. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matveyenko AV, Butler PC. Relationship between beta-cell mass and diabetes onset. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10(Suppl 4):23–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00939.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazor-Aronovitch K, Landau H, Gillis D. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment of congenital hyperinsulinism. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2009;6:424–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MI. Casting a wider net for diabetes susceptibility genes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1039–1040. doi: 10.1038/ng0908-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mears D. Regulation of insulin secretion in islets of Langerhans by Ca(2+)channels. J Membr Biol. 2004;200:57–66. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0692-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Nagashima K, Tashiro F, Kotake K, Yoshitomi H, Tamamoto A, Gonoi T, Iwanaga T, Miyazaki J, Seino S. Defective insulin secretion and enhanced insulin action in KATP channel-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10402–10406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Tashiro F, Iwanaga T, Nagashima K, Yoshitomi H, Aihara H, Nitta Y, Gonoi T, Inagaki N, Miyazaki J, Seino S. Abnormalities of pancreatic islets by targeted expression of a dominant-negative KATP channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11969–11973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami K, Yokokura M, Ishizuka N, Seino S. Normalization of Intracellular Ca2+ Induces a Glucose-responsive State in Glucose-unresponsive beta -Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:25277–25282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussig K, Staiger H, Machicao F, Kirchhoff K, Guthoff M, Schafer SA, Kantartzis K, Silbernagel G, Stefan N, Holst JJ, Gallwitz B, Haring HU, Fritsche A. Association of type 2 diabetes candidate polymorphisms in KCNQ1 with incretin and insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2009;58:1715–1720. doi: 10.2337/db08-1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestorowicz A, Glaser B, Wilson BA, Shyng SL, Nichols CG, Stanley CA, Thornton PS, Permutt MA. Genetic heterogeneity in familial hyperinsulinism. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1119–1128. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature. 2006;440:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature04711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG, Koster JC. Diabetes and insulin secretion: whither KATP? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E403–412. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00168.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG, Koster JC, Remedi MS. beta-cell hyperexcitability: from hyperinsulinism to diabetes. Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 2007;9(Suppl 2):81–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG, Shyng SL, Nestorowicz A, Glaser B, Clement JP, Gonzalez G, Aguilarbryan L, Permutt MA, Bryan J. Adenosine Diphosphate As an Intracellular Regulator Of Insulin Secretion. Science. 1996;272:1785–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen EM, Hansen L, Carstensen B, Echwald SM, Drivsholm T, Glumer C, Thorsteinsson B, Borch-Johnsen K, Hansen T, Pedersen O. The E23K variant of Kir6.2 associates with impaired post-OGTT serum insulin response and increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:573–577. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Du XL, Yamagishi S, Matsumura T, Kaneda Y, Yorek MA, Beebe D, Oates PJ, Hammes HP, Giardino I, Brownlee M. Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature. 2000;404:787–790. doi: 10.1038/35008121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njolstad PR, Sagen JV, Bjorkhaug L, Odili S, Shehadeh N, Bakry D, Sarici SU, Alpay F, Molnes J, Molven A, Sovik O, Matschinsky FM. Permanent neonatal diabetes caused by glucokinase deficiency: inborn error of the glucose-insulin signaling pathway. Diabetes. 2003;52:2854–2860. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njolstad PR, Sovik O, Cuesta-Munoz A, Bjorkhaug L, Massa O, Barbetti F, Undlien DE, Shiota C, Magnuson MA, Molven A, Matschinsky FM, Bell GI. Neonatal diabetes mellitus due to complete glucokinase deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344:1588–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama K, Minami K, Ishizaki K, Fuse M, Miki T, Seino S. Spontaneous recovery from hyperglycemia by regeneration of pancreatic beta-cells in Kir6.2G132S transgenic mice. Diabetes. 2006;55:1930–1938. doi: 10.2337/db05-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page R, Hattersley A, Turner R. Beta-cell secretory defect caused by mutations in glucokinase gene. Lancet. 1992;340:1162–1163. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93192-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino AA, Bennett MJ, Stanley CA. Hyperinsulinism in infancy and childhood: when an insulin level is not always enough. Clinical Chemistry. 2008;54:256–263. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.098988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe L, Frayling TM, Weedon MN, Mari A, Tura A, Ferrannini E, Walker M. Beta cell glucose sensitivity is decreased by 39% in non-diabetic individuals carrying multiple diabetes-risk alleles compared with those with no risk alleles. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1989–1992. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson ER, Flechtner I, Njolstad PR, Malecki MT, Flanagan SE, Larkin B, Ashcroft FM, Klimes I, Codner E, Iotova V, Slingerland AS, Shield J, Robert JJ, Holst JJ, Clark PM, Ellard S, Sovik O, Polak M, Hattersley AT, Neonatal Diabetes International Collaborative, G. Switching from insulin to oral sulfonylureas in patients with diabetes due to Kir6.2 mutations.[see comment] New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:467–477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereverzev A, Mikhna M, Vajna R, Gissel C, Henry M, Weiergraber M, Hescheler J, Smyth N, Schneider T. Disturbances in glucose-tolerance, insulin-release, and stress-induced hyperglycemia upon disruption of the Ca(v)2.3 (alpha 1E) subunit of voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels. Molecular Endocrinology. 2002;16:884–895. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.4.0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertusa JA, Sanchez-Andres JV, Martin F, Soria B. Effects of calcium buffering on glucose-induced insulin release in mouse pancreatic islets: an approximation to the calcium sensor. J Physiol. 1999;520(Pt 2):473–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfutzner A, Lorra B, Abdollahnia MR, Kann PH, Mathieu D, Pehnert C, Oligschleger C, Kaiser M, Forst T. The switch from sulfonylurea to preprandial short-acting insulin analog substitution has an immediate and comprehensive beta-cell protective effect in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2006;8:375–384. doi: 10.1089/dia.2006.8.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson LH. Beta-cell ion channels: keys to endodermal excitability. Hormone Metabolic Research. 1999;31:455–461. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson LH, Rosenberg MP, Kuznetsov A, Lancaster ME, Worley J.F.r., Roe MW, Dukes ID. Delayed rectifier K+ channel overexpression in transgenic islets and beta-cells associated with impaired glucose responsiveness. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:27787–27790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platzer J, Engel J, Schrott-Fischer A, Stephan K, Bova S, Chen H, Zheng H, Striessnig J. Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L-type Ca2+ channels. Cell. 2000;102:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poitout V, Robertson RP. Glucolipotoxicity: fuel excess and beta-cell dysfunction. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:351–366. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JR, Shaw NJ, Barrett TG, Hattersley AT, Ellard S, Gloyn AL. Permanent neonatal diabetes in an Asian infant. J Pediatr. 2005;146:131–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentki M, Matschinsky FM. Ca2+, cAMP, and phospholipid-derived messengers in coupling mechanisms of insulin secretion. Physiological Reviews. 1987;67:1185–1248. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1987.67.4.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remedi MS, Koster JC, Patton BL, Nichols CG. ATP-Sensitive K+ Channel Signaling in Glucokinase-Deficient Diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:2925–2931. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remedi MS, Kurata HT, Scott A, Wunderlich FT, Rother E, Kleinridders A, Tong A, Bruning JC, Koster JC, Nichols CG. Secondary consequences of beta cell inexcitability: identification and prevention in a murine model of K(ATP)-induced neonatal diabetes mellitus. Cell Metab. 2009;9:140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remedi MS, Nichols CG. Chronic antidiabetic sulfonylureas in vivo: reversible effects on mouse pancreatic beta-cells. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remedi MS, Rocheleau JV, Tong A, Patton BL, McDaniel ML, Piston DW, Koster JC, Nichols CG. Hyperinsulinism in mice with heterozygous loss of K(ATP) channels. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2368–2378. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribar TJ, Epstein PN, Overbeek PA, Means AR. Targeted overexpression of an inactive calmodulin that binds Ca2+ to the mouse pancreatic beta-cell results in impaired secretion and chronic hyperglycemia. Endocrinology. 1995;136:106–115. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.1.7828519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson CC, Hussain K, Jones PM, Persaud S, Lobner K, Boehm A, Clark A, Christie MR. Low levels of glucose transporters and K+ATP channels in human pancreatic beta cells early in development. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1000–1005. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0644-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel MJ, Boora P, Steckley D, de Vries G, Light PE. Kir6.2 polymorphisms sensitize beta-cell ATP-sensitive potassium channels to activation by acyl CoAs: a possible cellular mechanism for increased susceptibility to type 2 diabetes? Diabetes. 2003;52:2630–2635. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe MW, Worley JF, 3rd, Mittal AA, Kuznetsov A, DasGupta S, Mertz RJ, Witherspoon SM, 3rd, Blair N, Lancaster ME, McIntyre MS, Shehee WR, Dukes ID, Philipson LH. Expression and function of pancreatic beta-cell delayed rectifier K+ channels. Role in stimulus-secretion coupling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:32241–32246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorsman P, Trube G. Calcium and delayed potassium currents in mouse pancreatic beta-cells under voltage-clamp conditions. Journal of Physiology. 1986;374:531–550. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustenbeck I. Desensitization of insulin secretion. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:1921–1935. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)00996-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako Y, Grill VE. A 48-hour lipid infusion in the rat time-dependently inhibits glucose- induced insulin secretion and B cell oxidation through a process likely coupled to fatty acid oxidation. Endocrinology. 1990;127:1580–1589. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-4-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakura H, Ashcroft SJ, Terauchi Y, Kadowaki T, Ashcroft FM. Glucose modulation of ATP-sensitive K-currents in wild-type, homozygous and heterozygous glucokinase knock-out mice. Diabetologia. 1998;41:654–659. doi: 10.1007/s001250050964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakura H, Bond C, Warren-Perry M, Horsley S, Kearney L, Tucker S, Adelman J, Turner R, Ashcroft FM. Characterization and variation of a human inwardly-rectifying-K-channel gene (KCNJ6): a putative ATP-sensitive K-channel subunit. FEBS Letters. 1995;367:193–197. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakura H, Wat N, Horton V, Millns H, Turner RC, Ashcroft FM. Sequence variations in the human Kir6.2 gene, a subunit of the beta-cell ATP-sensitive K-channel: no association with NIDDM in while Caucasian subjects or evidence of abnormal function when expressed in vitro. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1233–1236. doi: 10.1007/BF02658512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samec S, Seydoux J, Dulloo AG. Role of UCP homologues in skeletal muscles and brown adipose tissue: mediators of thermogenesis or regulators of lipids as fuel substrate? FASEB Journal. 1998;12:715–724. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.9.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargsyan E, Ortsater H, Thorn K, Bergsten P. Diazoxide-induced beta-cell rest reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress in lipotoxic beta-cells. J Endocrinol. 2008;199:41–50. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]