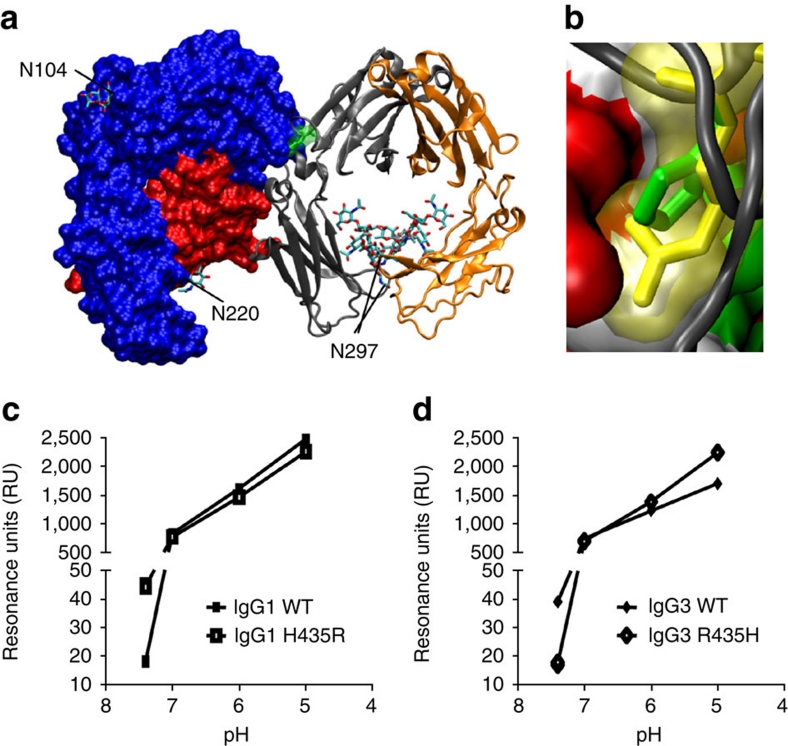

Figure 3. The influence of the Histidine versus Arginine at position 435 on FcRn binding at different pH.

(a) The crystal structure of FcRn with IgG–Fc part, showing the orientation of the amino acid 435 of IgG in yellow. N-linked glycans are labelled according to their occurrence in FcRn and Fc. (b) A close-up showing the side chain of amino acid 435 of IgG (histidine, in green) in the binding pocket of FcRn. When arginine (present at this position in IgG3) was modelled into this position (yellow), it protrudes into the FcRn surface area (non-polar residues in white, positively charged amino acids in blue, negatively charged residues in red and polar residues in green), suggesting steric hindrance. Histidine at this position alters its charge at pH 6.5 and lower (positive charge, resulting in FcRn binding) versus neutral pH (no charge, resulting in release of IgG from FcRn)22. Arginine in this position, however, is positively charged at both low and neutral pH, possibly resulting in better binding of IgG3 at neutral pH. The crystallographic coordinates51 (accession 1I1A) were modelled using DeepView 4.03 (ref. 52) and VMD 1.9 (ref. 53). (c,d) The importance of this amino acid difference between IgG1 and IgG3 was tested biochemically by injecting 500 nM recombinant IgG over shFcRn-coupled CM5 sensor chips at different pH. IgG3 (d) bound FcRn better than IgG1 (c) at neutral pH, but the situation was reversed at acidic pH. IgG1–H435R mutant gained IgG3-like characteristics, binding better at neutral pH, but worse at low pH (c). Likewise, IgG3 behaved like IgG1 after replacing the R435 with H435, binding relatively worse at neutral pH, but better at low pH (d), confirming that two opposing factors (steric hindrance versus charge) may contribute to the observed inhibition by IgG1 on FcRn-mediated IgG3 transport. The data in (c,d) are presented as individual data points connecting the means from two independent injections with a line.