Abstract

A combination of mandelic acid and N-bromosuccinimide efficiently converts prochiral alkenes into a readily separable 1:1 mixture of the bromomandelates. The diastereomerically-pure bromomandelates are then converted into a variety of enantiomerically-pure products. Terminal alkenes are converted into enantiomerically-pure epoxides. Cyclohexene is converted into enantiomerically-pure cis 2-azidocyclohexanol and cis 2-phenylthiocyclohexanol.

Introduction

Sharpless asymmetric epoxidation1a and asymmetric dihydroxylation1b are workhorses of modern organic synthesis. More recently, Jacobsen epoxidation2a and Shi epoxidation2b have also become important. Epoxides of terminal alkenes, however, cannot be prepared directly in acceptable enantiomeric excess with any of these protocols. Enantiomerically-enriched epoxides of such alkenes are currently derived by catalytic asymmetric hydrolysis of the racemic epoxides.3 The epoxides of simple cyclic alkenes such as 5a are prochiral. Enantiomerically-enriched products from such epoxides are currently accessed by chiral catalytic nucleophilic opening4 or by resolution.5 We have found (Scheme 1) that mandelic acid reacts with terminal alkenes such as 1a in the presence of NBS to give the readily separated 1:1 mixture of diastereomeric secondary mandelates 2a and 3a. The diastereomeric bromomandelates from cyclic alkenes are also readily separated. This provides a facile entry to chiral pool starting materials such as 4a and 8.

SCHEME 1.

Results and Discussion

We envisioned that conversion of alkene 1a to the bromohydrin followed by esterification with an enantiomerically-pure acid could lead to a separable mixture of diastereromeric bromo esters. The known6 HPLC separation of diastereomeric secondary mandelates led us to this inexpensive ($0.23/mmol), easily-handled acid. We were pleased to observe that the (S)-mandelates 2a and 3a of the enantiomeric secondary bromohydrins derived from 1a were readily separated by silica gel chromatography.7 Methanolysis of 3a delivered the epoxide 4a as a single enantiomer (99% ee, chiral HPLC).

The success of this separation led us to devise a one-step protocol for the conversion of an alkene to the mixture of bromomandelates. To our surprise, we found that in contrast to halolactonization, intermolecular alkene bromoesterification had not been developed as a synthetic method.8 We have found that the key was the use of the hindered pyridine 2,6-lutidine as the base for the reaction. For simple terminal alkenes, the mixture of bromomandelates formed efficiently, and the diastereomeric secondary mandelates were indeed easy to separate. For example, from alkene 1a, TLC Rf’s, (isolated yields): 3a 0.62, (26%), 2a 0.54 (27%), followed by the 1:1 mixture of the primary mandelates 0.46 (25%). Other monosubstituted alkenes (Table 1) worked equally well. The diastereomers 2 and 3 were readily distinguished by 1H NMR of the methines: for 2, δ 3.47–3.50, for 3 δ 3.35–3.39. Relative configurations were assigned by analogy to 3b, 3d and 3e, each of which led to an epoxide of known optical rotation.

Table 1.

Bromomandelation of terminal alkenes.

|

Both of the diastereomers 2a and 3a could be converted to the same enantiomer of the epoxide 4a. Direct exposure of 3a to KOH gave 4a (92% yield, Table 1). Exposure of 2a (Scheme 2) to 4-methoxyphenol in the presence of KOH gave the alcohol 9. The derived mesylate 10 was deprotected12 to give, after cyclization, the same enantiomer 4a of the epoxide (64% yield overall from 2a). The net yield of the enantiomerically-pure epoxide 4a from the alkene 1a was thus 41%, comparable to the yield expected from alkene epoxidation followed by enantioselective hydrolysis.

SCHEME 2.

A substantial advantage of this approach is that it provides the single enantiomer epoxides (4a – 4e) directly from the chromatographically-pure bromomandelates. The diastereomers 2 and 3 are readily distinguishable by TLC and by 1H NMR. There is no need to monitor a catalyst-mediated enantioselective hydrolysis by the more cumbersome and expensive methods of chiral HPLC or chiral GC. On a larger scale, the individual diastereomers of the bromomandelates can alternatively be purified by cystallization (Table 2, Entry 2). Further, for low molecular weight epoxides, the diastereomerically-pure bromomandelate precursors are more convenient to store and to handle than are the epoxides themselves.

Table 2.

Bromomandelation of cyclic alkenes.

|

Yields based on limiting alkene.

Relative configurations assigned in analogy to 6a and 7a.

Diastereomers separated by low temperature differential crystallization.

Encouraged by these results, we undertook (Table 2) the bromomandelation of prochiral cyclic alkenes. Again, the bromomandelates were readily separable [From 5a, TLC Rf’s, (isolated yields): 7a 0.51 (40%), 6a 0.40 (41%)]. Consistently, the 1H NMR chemical shifts of the brominated methines of 7a – 7e were downfield (δ 0.13 – δ 0.33) from the 1H NMR chemical shifts of the brominated methines of 6a – 6e.

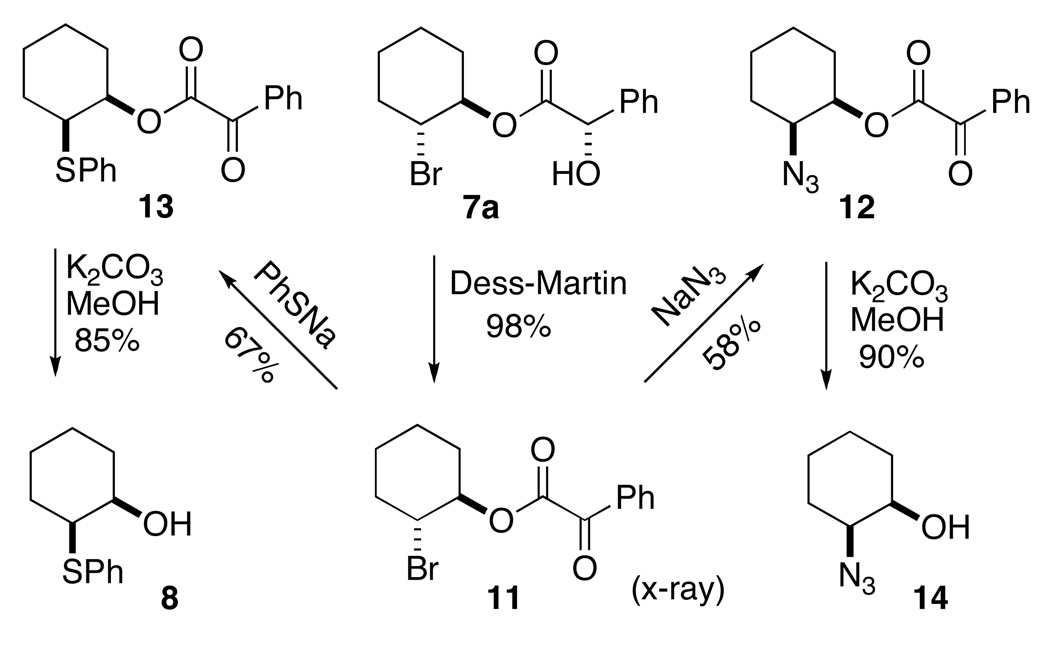

We briefly investigated nucleophilic displacement on 7a. The secondary bromide of 7a (Scheme 2) participated more efficiently in nucleophilic displacement after oxidation to the corresponding ketone 11. It is particularly noteworthy that these displacements, to give 12 and 13, led to the enantiomerically-pure cis derivatives 813 and 14,5,14 not directly available by other means. Indeed, the simple alcohol 813 had not previously been described in enantiomerically-pure form. X-ray analysis of the crystalline 9 allowed assignment of the absolute configuration of 7a.

Conclusion

The route to chiral pool starting materials that we have described here is operationally simple, and routinely delivers 99% e.e. products. We expect that it will have broad application in exploratory synthesis.

Experimental Section

Bromomandelation of terminal alkenes: Method A

A mixture of (S)-mandelic acid (350 mg, 2.3 mmol) and 2,6-lutidine (278 mg, 2.6 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (4 mL) was purged with N2 for 10 min. Alkene (1.00 mmol) was added. After stirring for another 2 min, NBS (267 mg, 1.5 mmol) was added in one portion while the solution was cooled by a water bath. The mixture was kept stirring overnight, the loaded onto a TLC mesh silica gel column and eluted.

Method B

A mixture of (S)-mandelic acid (305 mg, 2.0 mmol) and 2,6-lutidine (268 mg, 2.5 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (4 mL) was purged with N2 for 10 min. Alkene (4 mmol) was added. After stirring for another 2 min, NBS (178 mg, 1.00 mmol) was added in one portion while the solution was cooled by a water bath. The mixture was kept stirring for overnight, then loaded onto a TLC mesh silica gel column and eluted.

From 342 mg of 1a, method A

Ester 3a (colorless oil, 149 mg, 26%); TLC Rf = 0.62 (25% MTBE/petroleum ether); [α]20D +21.9 (c = 1.35, CHCl3); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 1.41 (m, 2H), 1.66 (m, 4H), 3.06 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.24 (m, 2H), 3.35 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 5.04 (m, 1H), 5.16 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.38 (m, 12H), 7.43 (m, 8H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ u 173.3, 144.4, 138.1, 86.5, 63.0, 33.1, 32.3, 29.6, 21.9; d 128.8, 128.7, 128.7, 127.9, 127.1, 126.7, 74.6, 73.0; IR (cm−1) 3499, 1736, 1597, 1491, 1448, 1182, 1068, 763, 746; HRMS calcd for C33H33BrNaO4 (M+Na): 595.1460, found: 595.1457.

Ester 2a (colorless oil, 155 mg, 27%); TLC Rf = 0.54 (25% MTBE/petroleum ether); [α]20D +31.3 (c = 1.20, CHCl3); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 0.88 (m, 2H), 1.42 (m, 4H), 2.83 (dt, J = 2.0 and 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.39 (dd, J = 6.0 and 11.4 Hz, 2H), 3.47 (dd, J = 6.0 and 11.0 Hz, 1H), 5.02 (m, 1H), 5.17 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.34 (m, 12H), 7.41 (m, 8H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ u 173.4, 144.4, 138.3, 86.5, 63.2, 33.5, 32.4, 29.5, 21.3; d 128.8, 128.7, 128.6, 127.9, 127.0, 126.6, 74.6, 73.0; IR (cm−1) 3466, 1737, 1596, 1491, 1448, 1181, 1068, 763, 746; HRMS calcd for C33H33BrNaO4 (M+Na): 595.1460, found: 595.1442.

The primary esters (1:1) were also eluted. TLC Rf = 0.46 (25% MTBE/petroleum ether).

From 178 mg of NBS, method B

Ester 3b (colorless oil, 79 mg, 23%), TLC Rf = 0.68 (30% Et2O/petroleum ether); [α]20D +34.7 (c = 0.95, CHCl3); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 1.28–1.49 (m, 4H), 1.71 (m, 2H), 2.05 (m, 2H), 3.28 (m, 2H), 3.37 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.94–5.10 (m, 3H), 5.20 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 5.77 (m, 1H), 7.35 (m, 3H), 7.44 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ u 173.3, 138.1, 115.0, 33.6, 33.1, 32.4, 28.5, 24.5; d 138.5, 128.7, 128.7, 126.7, 74.7, 73.1; IR (cm−1) 3469, 1737, 1454, 1181, 1067, 912, 732; HRMS calcd for C16H20BrO2 (M-OH): 323.0647, found: 323.0632.

Ester 2b (white solid, mp 53–54°C, 89 mg, 26%).; TLC Rf = 0.61 (30% Et2O/petroleum ether); [α]20D +66.6 (c = 0.9, CHCl3); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 0.94 (m, 2H), 1.16 (m, 2H), 1.54 (m, 2H), 1.82 (m, 2H), 3.43 (m, 2H), 3.50 (dd, J = 4.8 and 11.2 Hz, 1H), 4.90 (m, 2H), 5.04 (m, 1H), 5.21 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 5.63(m, 1H), 7.35 (m, 3H), 7.44 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ u 173.4, 138.4, 114.8, 33.6, 33.5, 32.4, 28.4, 24.0; d 138.5, 128.7, 126.7, 74.7, 73.0; IR (cm−1) 3438, 1734, 1455, 1203, 1101, 912, 737; HRMS calcd for C16H20BrO2 (M-OH): 323.0647, found: 323.0638.

The primary esters (1:1) were also eluted. TLC Rf = 0.57 (30% Et2O/petroleum ether).

Epoxide formation, Method A

To a solution of diastereo-pure bromomandelate (1 equiv) in methanol (0.1 M) was added K2CO3 (5 equiv), and the mixture was stirred at r.t. for 20 min. When the reaction was complete (monitored by TLC), methanol was removed at reduced pressure and Et2O was added. The mixture was filtered with Et2O and the combined filtrate was concentrated. The residue was chromatographed to provide enantio-enriched epoxide.

Epoxide 4a

(Method A, colorless solid, mp 54–55°C, 63 mg, 92%), from 110 mg of 3a, TLC Rf = 0.40 (10% Et2O/petroleum ether); [α]20D −7.2 (c = 1.0, CHCl3); The enantiomeric excess was measured to be 99.0% by HPLC using a CHIRALDALCEL OD column, eluting at 1 mL/min with 99.0/1.0 hexane/isopropanol, monitored at 250 nm, retention time: 7.75 min (R-epoxide), 8.77 min (S-epoxide). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 1.45–1.73 (m, 6H), 2.43 (dd, J = 2.8 and 4.8 Hz, 1H), 2.72 (dd, J = 4.0 and 4.8 Hz, 1H), 2.88 (m, 1H), 3.07 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 7.20 (m, 3H), 7.29 (m, 6H), 7.44 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ u 144.5, 86.5, 63.4, 47.2, 32.5, 29.9, 22.9; d 128.8, 127.8, 127.0, 52.4; IR (cm−1) 1596, 1490, 1448, 1219, 1154, 1076, 1032, 899, 747; HRMS calcd for C25H26O2 (M+): 358.1933, found: 358.1918.

Synthesis of Epoxide 4a from Ester 2a

A mixture of 2a (145 mg, 0.25 mmol), KOH (70 mg, 1.25 mmol) and 4-methoxyphenol (155 mg, 1.25 mmol) in dry THF (1.25 mL) in a thick-wall tube was purged with N2 for 10 min. This tube was sealed and heated to 95°C for 16 h with magnetic stirring. The cooled mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate and 5% aqueous NaOH. The combined organic extract was dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated. The residue was chromatographed to give the alcohol 9 (colorless oil, 105 mg, 0.22 mmol, 86%). TLC Rf = 0.34 (40% MTBE/petroleum ether); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 1.41–1.72 (m, 6H), 2.47 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.08 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 3.86 (dd, J = 2.8 and 9.2 Hz, 1H), 3.93 (m, 1H), 6.81 (s, 4H), 7.20 (m, 3H), 7.27 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ u 154.1, 152.8, 144.5, 86.4, 73.0, 63.4, 32.9, 30.0, 22.3; d 128.7, 127.8, 126.9, 115.6, 114.8, 70.2, 55.8.

A mixture of alcohol 9 (105 mg, 0.22 mmol), DMAP (3 mg, 0.024 mmol) and Et3N (67 mg, 0.66 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 was cooled to 0°C, and mesyl chloride (38 mg, 0.33 mmol) was added in one portion. The solution was kept stirring overnight, then partitioned between water and CH2Cl2. The combined organic extract was dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated. The residue was chromatographed to give the mesylate 10 (white crystals, mp 123–124°C, 104 mg, 0.19 mmol, 85%), TLC Rf = 0.34 (40% MTBE/petroleum ether); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 1.47–1.83 (m, 6H), 3.08 (m, 5H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 4.01 (m, 2H), 4.94 (m, 1H), 6.81 (m, 4H), 7.21 (m, 3H), 7.29 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H), 7.43 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ u 154.5, 152.2, 144.4, 86.5, 70.1, 63.1, 31.6, 29.7, 21.9; d 128.8, 127.9, 127.0, 115.6, 115.0, 81.7, 55.8, 38.8.

The mixture of mesylate 10 (104 mg, 0.19 mmol) in THF/H2O (4:1, 1.25 mL) was cooled to −5°C and ammonium cerium nitrate (312 mg, 0.57 mmol) was added in one portion. The reaction was monitored by TLC, and after 30 min, the reaction mixture was partitioned between water and ethyl acetate. The combined organic extract was dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated. The residue was re-dissolved in MeOH (2 mL) and K2CO3 (105 mg, 0.76 mmol) was added in one portion. After 20 min, the reaction was complete (monitored by TLC). Methanol was removed at reduced pressure and the residue was filtered with Et2O. The combined filtrate was concentrated and the residue was chromatographed to provide enantioenriched expoxide 4a (58 mg, 0.16 mmol, 88%. The overall yield from 2a was 64%). The enantiomeric excess was measured to be 99.0% under the conditions outlined above.

Epoxide formation, Method B

To a solution of diastereo-pure bromomandelate (1 equiv) in dry Et2O (0.1 M) was added KOH pellets (4 equiv), and the mixture was stirred for 2–3.5 h (monitored by TLC). When the reaction was complete, the reaction mixture was filtrated with Et2O. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was distilled bulb-to-bulb (pot = 110–130°C, 150 mm Hg) to give the epoxide as a clear oil.

Epoxide 4b

(method B, colorless oil, 205 mg, 89%), from 625 mg of 3b, TLC Rf = 0.71 (25% Et2O/petroleum ether); [α]20D −9.9 (c = 1.3, CHCl3), lit [α]20D −10.1 (c = 1.50, CH2Cl2.). Data identical with those reported.8

Bromomandelation of cyclic alkenes

A mixture of (S)-mandelic acid (609 mg, 4.0 mmol), 2,6-lutidine (535 mg, 5.0 mmol) and alkene (2.0 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (6 mL) was stirred for 10 min. NBS (356 mg, 2.0 mmol) was added in one portion while the solution was cooled by a water bath. The mixture was stirred overnight, added to TLC mesh silica gel column and eluted.

From 164 mg of 5a

Ester 7a (colorless oil, 250 mg, 40%), TLC Rf = 0.51 (30% Et2O/petroleum ether); [α]20D +14.7 (c = 1.65, CHCl3); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 1.28 (m, 3H), 1.62 (m, 2H), 1.90 (m, 2H), 2.34 (m, 1H), 3.42 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (m, 1H), 4.96 (dt, J = 4.4 and 9.6 Hz, 1H), 5.22 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (m, 3H), 7.42 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ u 172.9, 138.4, 35.6, 30.7, 25.4, 23.1; d 128.7, 128.6, 126.8, 77.9, 73.0, 52.1; IR (cm−1) 3447, 1732, 1453, 1186, 1067, 734; HRMS calcd for C14H17O3 (M-Br): 233.1178, found: 233.1188.

Ester 6a (white solid, mp 88–89°C, 259 mg, 41%); TLC Rf = 0.40 (30% Et2O/petroleum ether); [α]20D +126.1 (c = 1.65, CHCl3); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 1.28 (m, 1H), 1.45 (m, 2H), 1.72 (m, 3H), 2.15 (m, 2H), 3.42 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (dt, J = 4.4 and 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.93 (m, 1H), 5.18 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (m, 3H), 7.43 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ u 172.9, 138.1, 35.1, 30.7, 25.0, 23.1; d 128.6, 128.6, 126.9, 77.7, 73.2, 51.4; IR (cm−1) 3435, 1733, 1451, 1182, 1067, 733; HRMS calcd for C14H17O3 (M-Br): 233.1178, found: 233.1179.

Supplementary Material

SCHEME 3.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM 60287). We thank Andrea J. Passarelli for a crucial experiment.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION. Experimental details, spectra for all new compounds, and .cif file for 11. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Hanson RM, Sharpless KB. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:1922. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:2483. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Zhang W, Loebach JL, Wilson SR, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:2801. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang ZX, Cao GA, Shi Y. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:7646. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For leading references to the catalytic kinetic enantioselective opening of terminal epoxides, see Nielsen LPC, Stevenson CP, Blackmond DG, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:1360. doi: 10.1021/ja038590z. Kim SK, Jacobsen EN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3952. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460369..

- 4.For leading references to the catalytic enantioselective opening of cyclohexene epoxide, see McCleland BW, Nugent WA, Finn MG. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:6656. Ready JM, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:2687. doi: 10.1021/ja005867b..

- 5.Ami E, Ohrui H. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1999;63:2150. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Whitesell JK, Reynolds D. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:3548.. (b) For the use of O-methyl mandelate esters to resolve pre-formed halohydrins, see Konopelski JP, Boehler MA, Tarasow TM. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:4966..

- 7.Taber DF. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:1351. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) For bromoacetoxylation of a terminal alkene, see Srikrishna A, Sundarababu G. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:481.. (b) For bromoacetoxylation of cyclohexene, see Dulcère JP, Rodríguez J. Synlett. 1992:347..

- 9.Herb C, Dettner F, Maier ME. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005;13:728. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow S, Kitching W. Tetrahedron Asymm. 2002;13:779. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paddon-Jones GC, McErlean CSP, Hayes P, Moore CJ, Konig WA, Kitching W. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:7487. doi: 10.1021/jo0159237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petitou M, Duchaussoy P, Choay J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:1389. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritter RH, Cohen T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:3718. [Google Scholar]

- 14.For the use of an enantiomerically-pure cis 2-aminocyclohexanol as an effective ligand for the enantioselective reduction of a ketone, see Schiffers I, Rantanen T, Schmidt F, Bergmans W, Zani L, Bolm C. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:2320. doi: 10.1021/jo052433w..

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.