Abstract

Gossypiboma or textiloma is used to describe a retained surgical swab in the body after an operation. Inadvertent retention of a foreign body in the abdomen often requires another surgery. This increases morbidity and mortality of the patient, cost of treatment, and medicolegal problems. We are reporting case of a 45-year-old woman who was referred from periphery with acute pain in abdomen. She had a surgical history of abdominal hysterectomy 3 years back, performed at another hospital. On clinical examination and investigation, twisted ovarian cyst was suspected. That is a cystic mass further confirmed by abdominal computerized tomography (CT). During laparotomy, the cyst wall was opened incidentally which lead to the drainage of a large amount of dense pus. In between pus, there was found retained surgical gauze that confirmed the diagnosis of gossypiboma.

Keywords: Complication, gossypiboma, retained foreign body, textiloma

INTRODUCTION

Gossypiboma, term is derived from the combination of Latin words “gossypium” (cotton) and the Swahilli “boma” (place of concealment).[1] Gossypiboma is a term used to describe a mass within the body that comprises a cotton matrix surrounded by a foreign body reaction. Another term, “textiloma” which originated from the “textilis” - weave in Latin and “oma” - disease, tumor, swelling in Greek. It refers both to a fabric body involuntarily left in the patient during surgery and the reactions secondary to its presence in the body.[2] Surgical mop retained in the abdominal cavity following surgery is a serious, but avoidable complication.[3] Two usual responses to retained mops are exudative inflammatory reaction with formation of abscess, or aseptic fibrotic reaction to develop a mass that leads to future complications.[4]

CASE REPORT

A 45-year-old female patient referred to our center with complains of acute pain and distention of the abdomen. She was a known case of diabetes and hypertension for the last 3 years with well controlled status. It was learned from her past history that she underwent abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy for menorrahagia due to fibroid uterus. Her general examinations and laboratory parameters were within normal limits. On abdominal examination, a vertical midline scar was present; a large cystic mass was felt ~20x20 cm size with restricted mobility and smooth surface. Patient was managed conservatory on line of acute abdomen. Abdominal ultrasonography showed a round mass of 16-18 cm size with fluid echogenicity in the right lower quadrant. In the abdominal-pelvic computerized tomography (CT) scan, a heterogeneous cystic soft tissue mass of 24 cm size was found in the right lower quadrant of abdomen [Figure 1]. She was planned for exploratory laparotomy under general anesthesia with suspected diagnosis of twisted ovarian cyst from incidentally left ovarian tissue. Abdomen was opened with low midline incision. The mass was intraperitoneal, lying between loops of the small intestine [Figures 2 and 3]. We took all the precautions to prevent rupture of the cyst. But, because of multiple adhesions, it ruptured with expulsion of yellow, thick pus in which a sponge was found [Figure 4]. Pus samples were sent in a sterile container for culture and sensitivity. The sponge was removed and peritoneal lavage was done. The abdomen was closed with all precautions and counts of sponges and instruments. The culture and sensitivity of pus was sterile. Postoperative period was uneventful and the patient recovered well. After 8 days, patient was discharged and advised to follow-up.

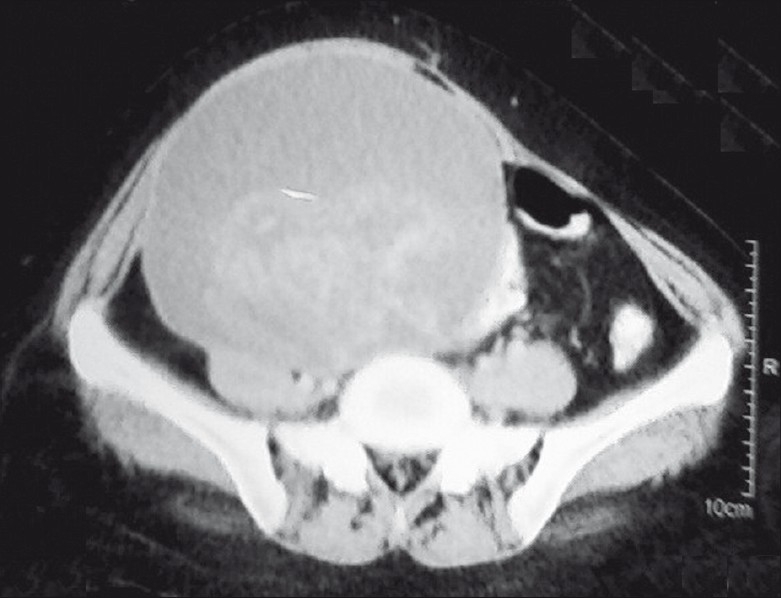

Figure 1.

CT scan of abdominopelvic region showing an extent of mass (cystic lesion with hyperechoic shadow inside)

Figure 2.

After evacuation of pus showing cyst wall (holding with artery forceps)

Figure 3.

After opening cyst wall retained foreign body in situ

Figure 4.

Specimen of a sponge as retained foreign body removed from abdomen

DISCUSSION

An acute surgical abdomen is one of those cases in which a patient needs emergent evaluation, treatment and likely requires emergent operative treatment. The causes can be mesenteric ischemia, appendicitis, cholecystitis, diverticulitis, bowel obstruction etc. An adult patient with an acute abdomen generally appears ill and has abnormal findings on physical examination There can be upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) signs and symptoms with signs of peritonitis. Management includes conservative treatment to surgical removal of definitive cause.[5] Gossypiboma cases generally have subacute or chronic presentation that is different from rest of the cases of acute abdomen.

This case is an important pearl to revisit the gossypiboma/retained postoperative foreign body (RFP). The gossypiboma cases can leads to embarrassment, humiliation, job loss, and law suit worldwide. Data concerning the actual incidence is difficult to estimate because of a low reporting rate due to medicolegal implication.[6] It varies between 1 out of 1,000–1,500 intra-abdominal operations and 1 out of 300–1,000 of all operations.[7] It is difficult to recognize a gossypiboma by using radiological screening if the sponge does not have any radiological marker on itself, because the cotton can simulate hematoma, granulomatous process, abscess formation, cystic masses or neoplasm.

The possibility of a retained foreign body should be in the differential diagnosis of any postoperative patient who presents with pain, infection, or palpable mass. The low index of suspicion is due to rarity of the condition and latency in the manifestation. If the diagnosis is made early, laparoscopic retrieval may be feasible.[8] According to recent review article by Wan et al., about retained sponges, gossypibomas were most commonly found in the abdomen (56%), pelvis (18%), and thorax (11%). The most common detection methods were computed tomography (61%), radiography (35%), and ultrasound (34%). Pain/irritation (42%), palpable mass (27%), and fever (12%) were the leading signs and symptoms, but 6% of cases were asymptomatic. Complications included adhesion (31%), abscess (24%), and fistula (20%). Average discovery time equalled 6.9 years with a median (quartiles) of 2.2 years (0.3-8.4 years).[9] In the case report which was conducted by Sumer et al., gossypiboma was exctraced from the abdominal cavity 23 years after caesarean operation. This is the longest time in the literature for forein body.[10]

The possible causes of sponge retention are emergency surgery, unexpected change in the surgical procedure, disorganization (e.g. poor communication), hurried sponge counts, long operations, unstable patient condition, inexperienced staff, inadequate staff numbers, and obesity. Most cases occurred when the sponge count was falsely pronounced correct at the end of surgery.[11] Gossypiboma most commonly occurs after gynecological and upper abdominal emergency surgical procedures, but it may also follow thoracic, orthopedic, urological, and neurosurgical procedures.[12] Because the symptoms of gossypiboma are usually nonspecific and may appear years after surgery, the diagnosis of gossypiboma usually comes from imaging studies and a high index of suspicion.

The clinical presentation of gossypiboma is variable and depends on the location of the sponge and the type of reaction. There are two types of foreign body reactions in pathology: an exudates reaction leading to abscess formation like our case and chronic internal or external fistula formation. Another is an aseptic fibrinous reaction resulting in adhesion, encapsulation, and eventual formation of granuloma. The latter usually presents much later than exudates reaction sequelae. They usually remain asymptomatic or present with pseudotumor syndrome. Common symptoms and signs of gossypiboma are abdominal distension, ileus, tenesmus, pain, palpable mass, diarrhea, abscess, and fistula formation, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss resulting from obstruction or a malabsorption type syndrome caused by the multiple intestinal fistulas or intraluminal bacterial overgrowth. Retained surgical sponges can cause serious consequences, such as bowel or visceral perforation, obstruction or fistula formation, sepsis or even death.[11,13] Intraabdominal gossypibomas can migrate into the ileum, stomach, colon or bladder without any apparent opening in the wall of these luminal organs.[14]

The inflammatory granulomatous reaction is the most likely cause of the extraosseous accumulation of technetium-99m-methylene diphosphonate (Tc-99m MDP) in gossypibomas as studied by nuclear medicine study.[15] Recently, New England Journal of Medicine published an article about risk factors of retained foreign bodies (RFBs). Of the 8 risk factors, the authors identified only 3 (emergency surgery, unplanned change in the operation, and body mass index [BMI]) were found to be statistically significant by multivariate logistic regression. The counting of sponges and instruments was not a significant predictor.[16]

The most impressive imaging finding of gossypiboma is the curved or banded radio-opaque lines on plain radiograph. The ultrasound feature is usually a well-defined mass containing wavy internal echogenic focus with a hypoechoic rim and a strong posterior shadow.[17] On CT, a gossypiboma may manifest as a cystic lesion with internal spongiform appearance with mottled shadows as bubbles, hyperdense capsule, concentric layering, and mottled shadows as bubbles or mottled mural calcifications.[18] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features of gossypiboma in the abdomen and pelvis, which include the delineation of a well-defined mass with a peripheral wall of low signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted imaging, with whorled stripes seen in the central portion and peripheral wall enhancement after intravenous gadolinium administration on T1-weighted imaging.[19]

Prevention of gossypiboma can be done by simple precaution like keeping a thorough pack count and tagging the packs with markers. Newer technologies are being developed that will hopefully decrease the incidence of RFP, like radiofrequency chip identification (RFID) by barcode scanner.[20] The overall objective of this system would be to eliminate errors in the sponge count by removing the human error factor. Furthermore, the sponge count protocol itself has been implicated as a hazard to patient safety.[21]

CONCLUSION

Present case is an important pearl that one must be aware of the risk factors that could lead to a gossypiboma and take measures to prevent it. Gossypibomas are uncommon, mostly asymptomatic, and hard to diagnose. Particularly, chronic cases do not show specific clinical and radiological signs for differential diagnosis. It should be included in the differential diagnosis of soft-tissue masses detected in patients with a history of a prior operation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rajput A, Loud PA, Gibbs JF, Kraybill WG. Diagnostic challenges in patients with tumors: Gossypiboma (foreign body) manifesting 30 years after laparotomy. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3700–1. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andronic D, Lupaşcu C, Târcoveanu E, Georgescu S. [Gossypiboma--retained textile foreign body] Chirurgia (Bucur) 2010;105:767–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibbs VC, Coakley FD, Reines HD. Preventable errors in the operating room: Retained foreign bodies after surgery--Part I. Curr Probl Surg. 2007;44:281–337. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wan YL, Ko SF, Ng KK, Cheung YC, Lui KW, Wong HF. Role of CT guided core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of a gosspypiboma: Case report. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:713–5. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell BH, Mendelson MH. Acute surgical abdomen the basics. Emerg Med. 2010;42:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uluçay T, Dizdar MG, SunayYavuz M, Aşirdizer M. The importance of medico-legal evaluation in a case with intraabdominal gossypiboma. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;198:e15–8. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lincourt AE, Harrell A, Cristiano J, Schrist C, Kercher K, Heniford BT. Retained foreign bodies after surgery. J Surg Res. 2007;138:170–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uranos S, Schauer C, Pfeifer J, Dagcioglu A. Laparoscopic removal of a large laparotomy pad forgotten in situ. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1995;5:77–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan W, Le T, Riskin L, Macario A. Improving safety in the operating room: A systematic literature review of retained surgical sponges. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22:207–14. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328324f82d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sümer A, Carparlar MA, Uslukaya O, Bayrak V, Kotan C, Kemik O, et al. Gossypiboma: Retained surgical sponge after a gynecologic procedure. Case Report Med. 2010;2010:1–3. doi: 10.1155/2010/917626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun HS, Chen SL, Kuo CC, Wang SC, Kao YL. Gossypiboma-retained surgical sponge. J Chin Med Assoc. 2007;70:511–3. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bani-Hani KE, Gharaibeh KA, Yaghan RJ. “Retained surgical sponges (gossypiboma)”. Asian J Surg. 2005;28:109–15. doi: 10.1016/s1015-9584(09)60273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruz RJ, Jr, Poli de Figueiredo LF, Guerra L. Intracolonic obstruction induced by a retained surgical sponge after trauma laparotomy. J Trauma. 2003;55:989–91. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000027128.99334.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moslemi MK, Abedinzadeh M. Retained Intraabdominal Gossypiboma, five years after bilateral orchiopexy. Case Report Med. 2010;2010:420357. doi: 10.1155/2010/420357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas BG, Silverman ED. “Focal uptake of Tc-99m MDP in a gossypiboma”. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33:290–1. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181662b41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gawande AA, Studdert DM, Orav EJ, Brennan TA, Zinner MJ. Risk factors for retained instruments and sponges after surgery. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:229–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zappa M, Sibert A, Vullierme MP, Bertin C, Bruno O, Vilgrain V. Postoperative imaging of the peritoneum and abdominal wall. J Radiol. 2009;90:969–79. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(09)73235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy CF, Stunell H, Torreggiani WC. Diagnosis of gossypiboma of the abdomen and pelvis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:W382. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim CK, Park BK, Ha H. Gossypiboma in abdomen and pelvis: MRI findings in four patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:814–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macario A, Morris D, Morris S. Initial clinical evaluation of a handheld device for detecting retained surgical gauze sponges using radiofrequency identification technology. Arch Surg. 2006;141:659–62. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.7.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers A, Jones E, Oleynikov D. Radio frequency identification (RFID) applied to surgical sponges. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1235–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]