Abstract

There is a need to explore why protocol-eligible subjects refuse participation in clinical trials. Without a clear understanding, participation by representative populations will be an ongoing obstacle to recruitment. This descriptive research study analyzes frequency data regarding a sample of 965 individuals who, despite being eligible for studies with the National Institute of Mental Health intramural program, declined research participation. Overall, responses regarding reasons for declining fell into the following five categories: a result of specific protocol issues; inconvenience; for other reasons not mentioned; financial reasons; and, lastly, decided to participate elsewhere. The results of this study identify common factors which suggest there are steps that investigators can take to better accommodate the needs of the public and, consequently, improve research participation.

Keywords: recruitment, clinical trials, refusal to participate

Why do eligible participants decline research participation? Little is known about the attitudes and willingness of the public to participate in medical research (Trauth et al., 2000). Most empirical research has focused on participants’ motives rather than the reasons why nonparticipants refuse (Williams et al., 2007). Although the general public expects, even demands, innovative prevention strategies and cutting-edge treatments, most individuals do not participate in research studies. Can investigators make changes to increase participation in research? Hunter et al. (1987) believe excluding data regarding eligible patients because of their refusal can raise questions about the adequacy of the selection and recruitment process. Ross et al. (1999), following a systematic review of three bibliographic databases from 1986–1996 related to barriers to recruitment in clinical trials, also identified the need to more clearly understand the reasons why clinicians and patients do or do not participate in clinical trials. And a more recent analysis of more than 100 trials showed that less than a third of trials achieved their original recruitment target and half were awarded an extension (McDonald et al., 2006).

This study examined the reasons why potential research subjects, who met initial inclusion criteria, chose to decline research participation in clinical trials for mental health disorders. Individuals who decline research participation are an important group to describe as they may increase our level of understanding regarding why otherwise eligible participants refuse to be in clinical trials. Further exploration could identify factors that are amenable to change and that help to determine possible solutions for improving recruitment and participation in research.

Method

Over the past decade, the Centralized Office of Recruitment and Evaluation (CORE) performed screening telephone interviews with potential research subjects for inclusion in National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) intramural research inpatient and outpatient studies in Bethesda, Maryland. The individuals included in this study were callers who initiated contact with NIMH because they were interested in being evaluated, and were then invited to participate in a diagnosis-specific research protocol for individuals with mental health disorders. Callers who contacted the investigators directly were excluded from this study. Most callers responded to advertisements they had seen in the community or heard on the radio. Generally, they called on behalf of themselves. For individuals with cognition limiting diagnoses, such as schizophrenia or Alzheimer’s disease, the screening questions were conducted with a primary caregiver identified by the participant. For pediatric studies, parents were interviewed.

Potential participants had a wide range of diagnoses, including, but not limited to, the following: autism, Alzheimer’s disease, anxiety, unipolar depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. After verbal consent was obtained to conduct a telephone interview, potential participants were asked a series of questions by advanced-practice mental health clinicians to ascertain whether they met the inclusion criteria for protocol participation. The results of these screening telephone interviews were maintained in a confidential NIMH database from 1999–2007. Applicants who met specific protocol inclusion criteria and were interested in continuing with evaluations were referred to the NIMH investigators conducting the appropriate clinical study for final evaluation.

Mental health clinicians at NIMH utilized the database to successfully screen and recruit thousands of applicants for inclusion in clinical trials. Using the recruitment database, we were able to identify a unique group of applicants who could be of interest to the research community: individuals who were determined to be eligible for mental health studies but who, ultimately, declined to participate. Data concerning these applicants were captured under the reason for decline category within the database.

The Office of Human Subjects Research (OHSR) at the National Institutes of Health reviewed and approved this study.

Results

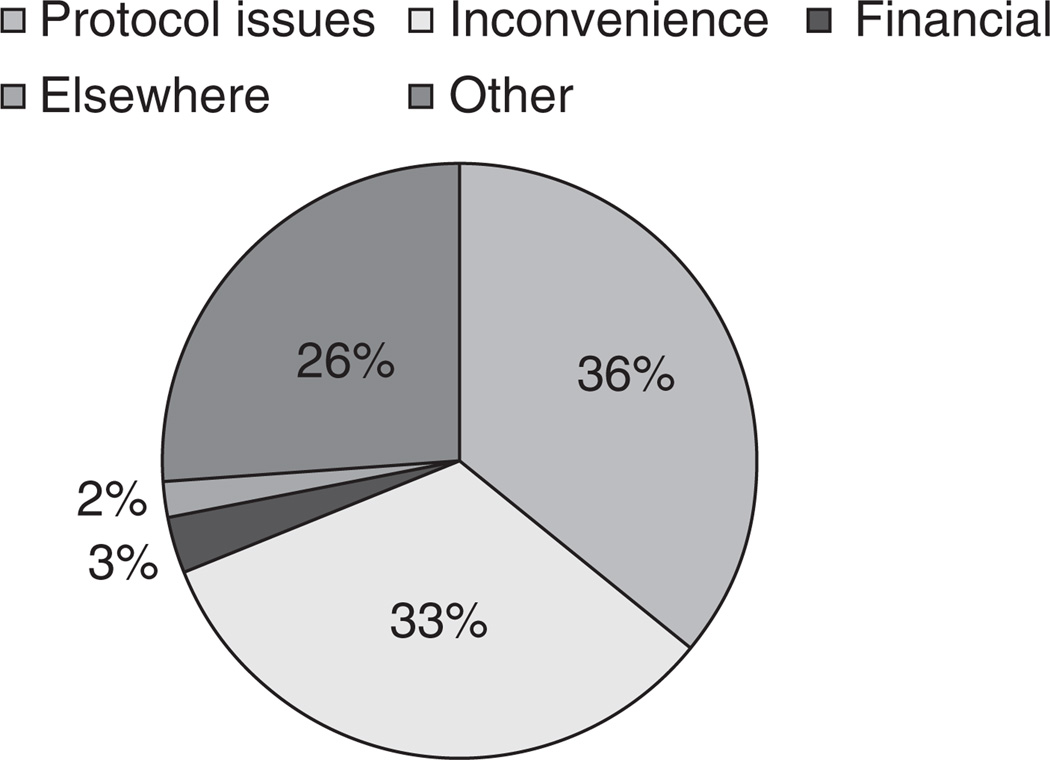

Between 1999 and 2007, 965 participants who were found to be eligible for participation in mental health research declined participation in NIMH intramural studies. By self-report, during interviews over the phone with psychiatric nurses and clinical social workers, responses of individuals who chose not to participate fell into the following categories: a result of specific protocol issues (36%, N = 345), inconvenience (33%, N = 323), financial reasons (3%, N = 29), decided to participate elsewhere (2%, N = 21), and for other reasons not mentioned above (26%, N = 261) (see Figure 1). These categories are further described below.

FIG. 1.

Reasons for Declining.

Protocol Issues

The individuals who declined research participation due to protocol issues (N = 345) reported the following reasons: length of inpatient studies; disinterest in a placebo-controlled study; concerns about symptoms getting worse due to washout from medications; unwillingness to participate in a washout phase; length of time spent in the Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)/Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanner; inability to participate in MRI/PET due to claustrophobia; length of the PET scan; radiation exposure due to the PET scan; refusal to have an arterial line placed; the side effects of the research medication were “too dangerous”; not willing to participate in a study that involves medications; unwilling to take a medication that has not been approved by the FDA for their specific disorder; only interested in open-label research studies; refusal to participate in the “lead-in” phase of a study which involved being placed on a mood stabilizer; discomfort with the requirement to take steps to prevent pregnancy in protection of an unborn fetus; or unwillingness to have their blood drawn. In addition, there were those who declined participation because they were solely interested in outpatient studies. These findings support the limited studies that have been done in the past, which also identified protocol issues such as preference for a specific treatment arm and fear of randomization (Penman et al., 1984; Llewellyn-Thomas et al., 1991; Jenkins et al., 1999) and the dislike of treatment being based on chance (Jenkins & Fallowfield, 2000) as reasons for declining participation.

Inconvenience and Lifestyle Issues

The second category, inconvenience/lifestyle issues (N = 323), overlaps with the aforementioned category but included responses that could be interpreted as more logistical in nature: inability to take time off of work; inability to travel to the Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD; distance to NIH; lack of flexibility in the participant’s schedule; and inability to participate during the work week and/or during work hours.

Other Reasons

The final category included those individuals who stated their reasons for declining participation was for other reasons not mentioned above (N = 261). Although the database made it optional for clinicians to ask the callers to elaborate, there were callers who were prompted by the interviewers to do so. Despite the limitations of this category, a few patterns could be identified. A common response within this category was from callers who chose to seek standard treatment in the community as an alternative to participating in research. Additional reasons for declining included: symptom remission; concerns about confidentiality; an interest in solely homeopathic and/or alternative remedies; religious/spiritual reasons; and individual concerns about losing benefits such as housing due to the duration of the inpatient studies.

Financial Reasons

The potential participants who declined due to financial reasons (N = 29) were individuals who had a mental health diagnosis but were solely interested in participating for pay. Although these callers were found to be eligible for certain clinical trials, if the potential participant was being referred to a protocol that did not offer compensation, they were not interested.

Studies Elsewhere

The few participants who decided to participate in studies elsewhere (N = 21) chose studies that, at the time of the screening process, were not available at the NIMH Intramural Research Program. For example, some callers wanted to participate in repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) research after the study had stopped actively recruiting subjects. These callers were offered other treatment protocols, but were not interested in trials that involved medications. In addition, there were individuals who called regarding specific research studies involving treatments such as: vagal nerve stimulation, herbal remedies, and/or therapies identified for specific disorders such as anorexia, bulimia, selective mutism, or trichotillomania. Typically, individuals within this category were so invested in a particular treatment modality that they were not open to the research alternatives presented, and voiced their decision to pursue studies elsewhere.

Discussion

Recruitment begins with protocol development and ends when the desired sample is obtained through the successful accrual of subjects. Consequently, understanding why potential participants decline is essential. With increased knowledge in this area, strategies to improve participation can be incorporated throughout the stages of the research cycle. A modest increase in participation of 2% to 3% could have a major impact, since completing a study in two years instead of three years could more rapidly improve standard of care treatments (Cornell University, Science Daily, 2007).

The primary purpose of the NIMH CORE database was to maintain recruitment and screening data. Consequently, the reason for decline category was narrow in its scope. In hindsight, it is evident that the five categories tracked by the database could be expanded.

Although the retrospective data reported in this paper are preliminary in scope and caution is warranted when considering larger implications, several themes are discernable. The preliminary findings suggest common factors that influence a potential participant’s decision to decline participation in clinical trials. Recruitment and participation in clinical trials could improve through increased awareness and education, by allowing more flexibility in protocols, and through maintaining specific recruitment data which include reasons for declining. Too often, recruitment strategies are considered as an afterthought and not as a critical component of the study. Educating investigators on best marketing and recruitment strategies, as well as encouraging them to consider these strategies when developing the protocol, would be beneficial. Based on this study, potential subjects reported they would be more willing to participate in clinical trials if studies were: offered in an outpatient setting; conducted over a shorter period of time; had less intrusive or time-consuming procedures; provided compensation; included alternative/homeopathic therapies; made available outside of the typical work schedule; or offered cutting-edge treatments that are not available to the general public. There were those who were solely interested in studies that involved treatment. Jenkins and Fallowfield (2000) had similar results; they found that significantly more patients declined entry to a trial with no treatment arm. Investigators may be able to improve recruitment and participation if they develop novel studies that involve cutting-edge treatments.

With studies that are currently open and recruiting, investigators could update their existing protocols through their respective institutional review boards during a continuing review, and eliminate unnecessary inclusion and/or exclusion criteria. Additionally, research teams could take into account the previous year’s recruitment refusal data and make simple modifications that would better accommodate the needs of the potential participants. Although excessive flexibility is not conducive to good research, extreme rigidity can have equally damaging consequences.

The individuals who were screened for participation in clinical trials had contacted NIMH for consideration in mental health studies. Due to this specific mode of entry, the generalizability of our findings may be limited. However, mental health issues are more prevalent than one might suspect. A recent national study conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) determined there were an estimated 45.1 million adults (19.9%) who dealt with mental illness, which was defined as having had a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder (excluding developmental and substance abuse disorders) of sufficient duration to meet diagnostic criteria in the DSM-IV (APA, 1994) in the United States over the course of the year 2009 (SAMSHA, 2010).

Given the limitations of descriptive research, a causal relationship among variables cannot be clearly identified or supported. The importance of querying each research participant and maintaining recruitment data that identifies reasons why potential participants decline is vital for the research cycle to be complete. When the voice of the public is heard and their needs are addressed, subject accrual will improve and advances in healthcare can be made.

Research Agenda

Participation in research is essential for the advancement of science, and the recruitment of adequate numbers of subjects is necessary for healthcare to progress. A recommendation made more than a decade ago by Van den Berg et al. (1997), “for good clinical practice and correct research, the number of patients refusing to participate in a clinical trial should be mentioned in all reports,” continues to provide appropriate advice for present-day investigators.

Strategies to improve participation rates should address reasons for nonparticipation, since low participation rates can lead to sampling bias, delays in completion, and increased costs (Williams et al., 2007). Biomedical research facilities would benefit from including detailed screening follow-up questions that identify specific reasons why potential subjects decline participation in studies, particularly when those individuals initiate contact and are found to be eligible for research participation in clinical trials. Further investigation could clarify modifiable factors and, in the long term, promote recruitment within clinical trials.

Best Practices

Educating clinicians who conduct screening interviews about the importance of maintaining clear and specific data regarding the reasons potential participants decline would be a helpful measure to identify criteria that may be amenable to change and helpful to future research endeavors. These data solely include those who expressed interest in research. Future studies could be designed to gather information from individuals who have never initiated contact nor expressed an interest in research participation.

Educational Implications

In order to improve participation in clinical trials, it is essential to educate investigators, the research team, and the public. Researchers who understand the preferences of potential participants ought to consider the factors that influence participant decisions, and make efforts to accommodate their needs (Candilis et al., 2006). Finally, educating potential subjects regarding clinical trials can increase understanding, help to establish rapport, and lay a foundation necessary for successful recruitment and participation. Williams et al. (BioMed Central, 2007) found that those individuals who declined did not reflect an objection to participating in research; rather their declining to participate frequently stemmed from barriers to or misunderstandings about the research project itself.

Participant and staff education regarding research procedures provided earlier in the recruitment process could focus on alleviating concerns and increasing the likelihood of participation. Overall, increased awareness among all of those involved, whether they are an investigator or a subject, is instrumental to the process and crucial to the research enterprise.

There are many helpful resources designed to inform the public and educate investigators. Education can involve something as simple as a verbal discussion with an advanced-practice clinician and/or the presentation of fact sheets and educational brochures. Recruitment experts within the National Institutes of Health recommend a selection of intranet links that provide helpful information necessary to make an informed decision about research participation. These unique resources were developed to increase public awareness and participation in clinical trials. They provide user-friendly information on general topics such as “What is a clinical trial?” to detailed information concerning the informed consent process as well as specific protocol criteria. The following resources have a wealth of information, useful to both the participant and investigator, and provide access to many helpful educational brochures, fact sheets, pamphlets, and videos in English and Spanish:

To access information regarding clinical trials and research participation:

To access information related to pediatric research and an educational video for children/families:

To access educational brochures that are free of charge for participants:

To access general information for professionals and participants:

Acknowledgment

This study was conducted with the support of the National Institute of Mental Health. Our gratitude goes to Dr. Donald Rosenstein, MD, for being one of the pioneers to spearhead CORE. We would like to thank Jean Murphy, RN, MSN, for the support and encouragement she gave to this research project and to Lisa Horowitz, PhD, for her editorial assistance. In addition, we would like to thank Dr. Christine Grady for highlighting the importance of recruitment issues and the need to better understand the desires of research participants during “The Ethical and Regulatory Aspects of Human Subject Research Conference” in 2002.

Biographies

Julie Brintnall-Karabelas is a Clinical Research Advocate with the Human Subjects Protection Unit at NIMH. While serving as a member of the IRB for the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, she developed an interest in addressing bioethical issues with vulnerable populations. She has a special interest in mental health and working with the terminally ill.

Susanna Sung is the Director, Marketing and Community Relations Unit at the NIMH, Intramural Research Program. She oversees recruitment support for clinical investigators at the NIMH IRB.

Mary Ellen Cadman is a Clinical Research Advocate with the Human Subjects Protection Unit at NIMH. She has worked at the National Institutes of Health since 1979 in both direct patient care as a senior clinical research nurse and, since 1999, as a monitor of the process of subject enrollment and of the ongoing participation of vulnerable subjects.

Carol Squires is a Clinical Research Advocate with the Human Subjects Protection Unit at NIMH. She has a special interest in human subject protections applied to the elderly, people with dementia, and individuals with mental health issues.

Katherine Whorton is a Clinical Research Advocate with the Human Subjects Protection Unit at NIMH. She specializes in the development and application of human subject’s protections for potentially vulnerable populations in research settings.

Maryland Pao is the Clinical Director of the National Institute of Mental Health and serves as Chief of the Psychiatry Consultation Liaison Service in the Hatfield Clinical Research Center at NIH and is the NIMH Clinical Fellowship Training Director. Her core research interests are in the complex interactions between somatic and psychiatric illnesses.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Candilis PJ, Geppert CM, Fletcher KE, Lidz CW, Appelbaum PS. Willingness of subjects with thought disorder to participate in research. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(1):159–165. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell University. How to improve patient participation in clinical trials. Science Daily. 2007 September 22; Retrieved May 1, 2010 from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/09/070917115305.htm.

- Hunter CP, Frelick RW, Feldman AR, Bavier AR, Dunlap WH, Ford L, Henson D, Macfarlane D, Smart CR, Yancik R, et al. Selection factors in clinical trials: Results from the Community Clinical Oncology Program Physician’s Patient Log. Cancer Treatment Reports. 1987;71(6):559–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins VA, Fallowfield LJ, Souhami A, Sawtell M. How do doctors explain randomized clinical trials to their patients? European Journal of Cancer. 1999;35(8):1187–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Reasons for accepting or declining to participate in randomized clinical trials for cancer therapy. British Journal of Cancer. 2000;82(11):1783–1788. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn-Thomas HA, McGreal MJ, Thiel EC, Fine S, Erlichman C. Patients’ willingness to enter clinical trials: Measuring the association with perceived benefits and preference for decision participation. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90124-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AM, Knight RC, Campbell MK, Entwistle VA, Grant AM, Cook JA, Elbourne DR, Francis D, Garcia J, Roberts I, Snowdon C. What influences recruitment to randomized controlled trials? A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials. 2006;7:7–9. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penman DT, Holland JC, Bahna GF, Morrow G, Schmale AH, Derogatis LR, Carnrike CL, Jr, Cherry R. Informed consent for investigational chemotherapy: Patients’ and physicians’ perceptions. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1984;2(7):849–855. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.7.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, Gillespie W, Russell I, Prescott R. Barriers to participation in randomized controlled trials: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1999;52(2):1143–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-39, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4609; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trauth JM, Musa MD, Siminoff L, Jewell IK, Ricci E. Public attitudes regarding willingness to participate in medical research studies. Journal of Health Social Policy. 2000;12(2):23–43. doi: 10.1300/J045v12n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg L, Lobatto RM, Zuurmond WWA, de Lange JJ, Wagemans MFM, Bezemert PD. Patients’ refusal to participate in clinical research. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 1997;14(3):287–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.1997.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Irvine L, McGinnis AR, McMurdo ME, Crombie IK. When “no” might not quite mean “no”; the importance of informed and meaningful non-consent: Results from a survey of individuals refusing participation in a health-related research project. Biomed Central Health Services Research. 2007 April 26; doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-59. Retrieved November 12, 2008 from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/7/59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]