Abstract

The immune response to recombinant adenoviruses is the most significant impediment to their clinical use for immunization. We test the hypothesis that specific virus-antibody combinations dictate the type of immune response generated against the adenovirus and its transgene cassette under certain physiological conditions while minimizing vector-induced toxicity. In vitro and in vivo assays were used to characterize the transduction efficiency, the T and B cell responses to the encoded transgene, and the toxicity of 1 × 1011 adenovirus particles mixed with different concentrations of neutralizing antibodies. Complexes formed at concentrations of 500 to 0.05 times the 50% neutralizing dose (ND50) elicited strong virus- and transgene-specific T cell responses. The 0.05-ND50 formulation elicited measurable anti-transgene antibodies that were similar to those of virus alone (P = 0.07). This preparation also elicited very strong transgene-specific memory T cell responses (28.6 ± 5.2% proliferation versus 7.7 ± 1.4% for virus alone). Preexisting immunity significantly reduced all responses elicited by these formulations. Although lower concentrations (0.005 and 0.0005 ND50) of antibody did not improve cellular and humoral responses in naïve animals, they did promote strong cellular (0.005 ND50) and humoral (0.0005 ND50) responses in mice with preexisting immunity. Some virus-antibody complexes may improve the potency of adenovirus-based vaccines in naïve individuals, while others can sway the immune response in those with preexisting immunity. Additional studies with these and other virus-antibody ratios may be useful to predict and model the type of immune responses generated against a transgene in those with different levels of exposure to adenovirus.

INTRODUCTION

Despite a concerted effort to develop recombinant adenoviruses for clinical gene transfer, the immune response induced by the virus continues to be the most significant limitation of this otherwise potent vector (20, 59). After systemic administration, virus rapidly binds to complement and clotting factors that promote cell adhesion and sequestration of virus by macrophages and dendritic and Kupffer cells (1, 3, 15, 49, 55). This and efficient transduction of hepatocytes stimulate release of numerous cytokines and chemokines into the circulation (15, 59). Immediate effects include thrombocytopenia and elevated liver enzymes, often transient and self-limiting. Virus-induced pathology can then progress further, manifesting significant tissue injury, multiorgan failure, and death (41). The innate response is further strengthened through Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent mechanisms (2, 31, 60). As a result, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-restricted CD8+ and MHC class II helper CD4+ T cells specific for targets expressing viral gene and transgene products are produced (22, 57, 58). In the context of gene transfer, these responses limit the duration of gene expression and compromise the potency of subsequent doses of vector in immunocompetent individuals. In contrast, the innate response to adenoviruses can effectively boost the immune response against an encoded antigen, making them attractive for immunization platforms (27, 28, 56). However, this response still hampers the clinical utility of the virus for this purpose.

Adenovirus serotype 5, used in 414 clinical trials to date (http://www.wiley.co.uk/genmed/clinical/), is ubiquitous in nature and infects humans frequently, making preexisting immunity to the virus prevalent in the general population. Although anti-adenovirus 5 antibody levels are generally low in children, they increase with age (52) and vary according to geographical location, with the lowest levels found in the United States (30 to 60% of the population positive), moderate levels in Europe and Asia (40 to 80% positive), and highest levels in sub-Saharan Africa (80 to 100% positive) (38). With the primary concern being neutralization of virus particles and failure to produce sufficient amounts of antigen required for protective immunity, early efforts to address the issue of preexisting immunity involved isolation and development of rare human and nonhuman adenovirus serotypes as carriers (17, 21, 43, 44). These vectors do evade neutralization by anti-adenovirus 5 antibodies; however, they are difficult to produce and elicit moderate immune responses against the encoded antigen. Genetic modification of hexon proteins, the primary site of antibody binding (50), covalent attachment of biocompatible polymers to the capsid to deter antibody binding, production of adenovirus chimeras from several different serotypes, and direct incorporation of antigen-specific epitopes into the virus capsid have improved the potency of adenovirus-based vaccines in those with preexisting immunity to some degree (6, 16, 23, 47, 51, 54).

Although reduction of the potency of an adenovirus-based vaccine in those with preexisting immunity to adenovirus 5 is a legitimate concern, recent results from a phase IIb clinical trial suggest that virus-antibody complexes can significantly influence the type of immune response generated by the vaccine carrier in a another way that may not be appropriate in some infectious disease models. In this trial, it was initially thought that adenovirus-antibody complexes triggered expansion of adenovirus-specific effector CD4+ cells, increasing the targets available for HIV infection (4, 36). Although it is still not clear if this was the primary cause of the outcome of that trial (32), this and the fact that development of alternative adenoviral vectors has not adequately addressed the issue of preexisting immunity highlight the fact that this immunological state in the general population is poorly characterized and not well understood.

In this report, we test the hypothesis that specific virus-antibody ratios dictate the types of immune responses generated against the virus and the transgene cassette under certain physiological conditions and that this information can be used to improve and predict the potency of adenovirus-based vaccines in certain patient populations. Experiments outlined in this paper were explicitly designed to identify specific virus-antibody combinations that promote potent immune responses to an encoded antigen and reduce virus-induced toxicity. In vitro and in vivo assays were used to assess the transduction efficiency, the T and B cell responses to the encoded transgene, and the toxicity profile of a single dose of a model recombinant virus premixed with neutralizing antibodies at various concentrations prior to administration to naïve mice. The utility of these complexes in animals with established preexisting immunity is also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus production.

Wild-type (VR-5; ATCC, Manassas, VA) and first-generation adenovirus serotype 5 vectors containing either Escherichia coli beta-galactosidase (AdlacZ) or enhanced green fluorescent protein (AdEGFP) were amplified and purified according to established methods (53). All experiments were performed with freshly purified virus.

Infectious titer assay.

Samples were serially diluted in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Cellgro DMEM; Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Medium was removed from 12-well plates (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA) seeded with 1.5 × 104 293 cells/well and replaced with 0.1 ml of the appropriate dilution of virus. After 2 h at 37°C, 1 ml of DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to each well. Sixteen hours later, medium was removed and cells were fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde. Beta-galactosidase activity was determined after treatment with the substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-beta-galactoside (Gold Biotechnology, St. Louis, MO) for 16 h at 37°C in the dark. Staining medium was removed and blue lac+ cells were tallied from a minimum of 20 microscope fields (approximately 48,000 cells). The number of infectious virus particles was calculated as described previously (13).

Plaque assay.

Plaque assays were performed according to established protocols (19). Aliquots of virus (250 μl), serially diluted in DMEM, supplemented with 2% FBS, were added to 293 cells for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were then overlaid with minimum essential medium (Gibco Invitrogen) containing agarose (0.8%, SeaPlaque; BioWhittaker Molecular Applications, Walkersville, MD), FBS (2%), and MgCl2 (10 mM). PFU were calculated as described previously (5).

Production of VACs.

Virus-antibody complexes (VACs) were formed by mixing freshly purified virus (1 × 1012 virus particles/ml) with a specific amount of stock anti-adenovirus serotype 5 antibody and gentamicin (20 μg/ml; Abraxis Pharmaceutical Products, Schaumburg, IL) in Protein LoBind microcentrifuge tubes (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY). Tubes were affixed to a rocking platform shaker (Ames aliquot mixer; Siemens Medical Solutions, Elkhart, IN) and gently agitated for 1 h at 37°C. Preparations were then placed on ice and immediately given to C57BL/6 mice. The timeline for dosing, sample collection, necropsy, and assessment of the immune response generated by VACs is summarized in Fig. 1.

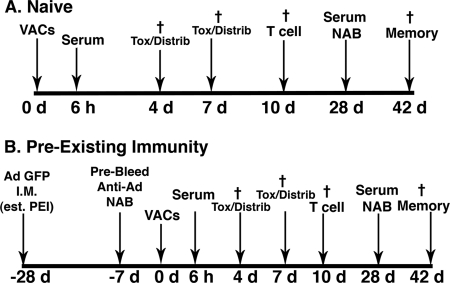

Fig 1.

Timeline for administration of virus-antibody complexes (VACs), sample collection, necropsy, and assessment of the immune response for naïve mice (A) and those with preexisting immunity (PEI) (B). Mice were given a single dose of 1 × 1011 virus particles mixed with different concentrations of anti-adenovirus antibodies (naïve mice) or 28 days after establishment of preexisting immunity by tail vein injection in a volume of 100 μl. Control mice were given 100 μl of sterile PBS and gentamicin in the same manner. Six hours after treatment, blood was collected from the saphenous vein and serum processed for assessment of cytokines, platelets, and serum transaminases. Blood was also collected on days 3 and 7 for assessment of serum transaminases and platelets. Mice from each group (n = 4) were sacrificed on days 4 and 7, and portions of liver and spleen were cryopreserved for sectioning and histochemical detection of beta-galactosidase. Remaining tissue and other organs (heart, kidney, lung, lymph nodes) were harvested and snap-frozen for assessment of virus distribution by real-time PCR. Ten days after treatment, mice (n = 5) were sacrificed and splenocytes processed for assessment of T cell responses. Tissue samples were also taken at this time point for assessment of virus distribution patterns. On day 28, blood was collected from the saphenous vein of remaining animals for characterization of anti-beta-galactosidase and anti-adenovirus antibodies. These animals (5 per group) were sacrificed on day 42 and splenocytes processed for assessment of immunological memory by CFSE staining and flow cytometry. †, terminal bleed and necropsy of animals at the denoted time point.

Characterization of neutralizing antibody stock and VACs. (i) Anti-adenovirus IgG isotyping.

The types of antibodies generated during production of the neutralizing antibody stock were identified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously (12). Briefly, high-binding polystyrene microtiter plates (Immulon 2HB; Thermo Scientific, Rochester, NY) were coated with 100 μl of AdlacZ (5 × 109 virus particles/well) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C, washed four times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, and blocked in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (ELISA grade; Sigma) for 2 h at room temperature. Serum dilutions used to form VACs were added to the antigen-coated plates for 2 h at room temperature. Plates were washed four times and incubated with horseradish peroxidasean (HRP)-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgM antibodies (1:2,000 dilution; Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were washed, p-nitrophenyl phosphate in diethanolamine buffer was added (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and optical densities (OD) were read at 450 nm on a microplate reader (Tecan USA, Research Triangle Park, NC).

(ii) Western blotting.

Adenovirus structural proteins obtained from 20 μg adenovirus (∼5 × 108 virus particles) were resolved in each individual lane of a 9% gel via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) microporous membranes using a Trans-blot Turbo transfer system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The membrane was then cut into individual lanes, and each was incubated with a specific serum dilution used to form VACs overnight at 4°C. Membranes were then incubated with an HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:25,000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were developed with the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and membranes were exposed to BioMax ML film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) for 30 min. Films were scanned and analyzed using Kodak 1D image analysis software (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY).

(iii) Dynamic light scattering.

Particle size of VACs was assessed with a DynaPro LSR laser light scattering detection system (Wyatt Technology Corporation, Santa Barbara, CA) according to established protocols (8).

Animal studies.

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas at Austin and are in accordance with the guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health for the humane treatment of animals.

Production of neutralizing antibody stock.

Serum used to form VACs was generated by immunizing 80 male C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice (6 to 8 weeks old; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) with 100 μg of density gradient-purified wild-type adenovirus 5. Virus was prepared as an emulsion with TiterMax Gold according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma-Aldrich). One hundred microliters of the final emulsion was injected subcutaneously. Two weeks later, mice were given a second dose prepared in the same manner. Blood was collected 2 weeks later from a representative cohort (n = 40) via the saphenous vein and serum screened for anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibodies (NAB). Animals were sacrificed and terminally bled 21 days later. Serum was collected, pooled, heat inactivated, and stored in LoBind microcentrifuge tubes at −80°C prior to use. The final NAB titer of this stock preparation was a 3,926 reciprocal dilution.

Establishment of preexisting immunity (PEI) to adenovirus.

PEI was established in male C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice (6 to 8 weeks) with 1 × 1011 particles of AdEGFP (total volume, 100 μl) by direct injection of 50 μl into each gastrocnemius muscle on the hind limb (Fig. 1B). Twenty-one days later, blood was collected and serum screened for anti-adenovirus NAB. Average anti-adenovirus NAB levels prior to administration of VACs across treatment groups was a 184.2 ± 32.4 reciprocal dilution. Mice were given VACs 7 days later (28 days post-PEI) by tail vein injection. Necropsy and sampling times are the same as for naïve mice (Fig. 1).

Chromium release assay.

Splenocytes were harvested on day 10, pooled according to treatment, and cultured for 5 days at a density of 6 × 106 cells/well in RPMI 1640 medium (Mediatech) with 10% FBS and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) in the presence of AdlacZ at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 PFU/cell in 24-well culture plates. Activation and cytolytic activity was determined by a classical chromium release assay in which MC57 (H-2b) target cells (∼1 × 106), infected for 24 h with AdlacZ (MOI, 100), were labeled with 100 μCi of 51Cr sodium (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed and plated in 96-well round-bottomed plates (BD Falcon) in DMEM containing 10% FBS at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well. Effector cells were then added at different effector:target ratios (100:1, 50:1, 25:1, 12:1, 6:1, and 3:1) and maintained at 37°C for 6 h. At this time, 100 μl of culture supernatant was removed from each well and counted in a gamma counter (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). The percentage of specific 51Cr release was calculated as [(cpm of sample – cpm of spontaneous release)/(cpm of maximal release – cpm of spontaneous release)] × 100. Spontaneous release was determined by assaying target cells in the absence of effectors. Maximum release was determined by addition of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to target cells in the absence of effectors. Data represent average values obtained from four wells.

Intracellular cytokine staining.

Splenocytes isolated from mice on day 10 were pooled according to treatment and ground through sterile strainers (70 μm; BD Falcon) into 50-ml conical tubes containing Liebovitz's L15 medium (Mediatech). Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and red blood cells were removed by resuspending the pellet in an equal volume of ACK lysis buffer (Quality Biological, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). After several washes, cells were adjusted to a density of 2 × 106/well in complete DMEM containing 10% FBS, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, penicillin (10,000 IU/ml), streptomycin (10,000 μg/ml) (Gibco, Invitrogen), 1 mM l-glutamine (HyClone, Salt Lake City, UT), 50 U/ml mouse interleukin-2 (IL-2) (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), 1 mM nonessential amino acids (Lonza), and 1 μg/ml brefeldin A (Sigma). Cells were cultured for 6 h at 37°C in round-bottom 96-well plates with a peptide (DAPIYTNV; 1 μg/well; New England Peptide, Gardner, MA) which contains the beta-galactosidase MHC class I restricted epitope for mice of the H-2b haplotype (34). Cells were pelleted, resuspended in PBS containing rat fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-mouse CD8a antibody (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA), and placed at 4°C for 30 min. Cells were washed 3 times, resuspended in Cytoperm (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and stored at 4°C for 30 min. Cells were then stained with rat phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody (BD PharMingen) for 30 min at 4°C. Positive cells were counted using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Over 250,000 events were captured per sample. Data were analyzed with FCS Express (DeNovo Software, Los Angeles, CA).

Carboxy fluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) staining.

Expansion of T cells in response to beta-galactosidase-specific T peptide was analyzed using the Vybrant CFDA SE cell tracer kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Splenocytes were harvested, and 2 × 106 cells from each animal were incubated in triplicate for 15 min with 1.5 μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFDA SE), at 37°C for 15 min. Cells were washed twice and resuspended in complete DMEM with or without the DAPIYTNV peptide (1 μg/well) and cultured for 5 days at 37°C. Staining for cell surface markers was performed for 30 min at 4°C with a cocktail of antibodies (PerCP-Cy5.5-labeled anti-CD8, PE-labeled anti-CD44, and APC-labeled anti-CD62L; BD PharMingen) and analyzed as described.

Detection of transgene-specific IgG.

Twenty-four hours prior to collection of serum, 96-well plates (Evergreen Scientific, Los Angeles, CA) were coated with beta-galactosidase (1 μg/well; enzyme immunoassay [EIA] grade; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) in PBS at 4°C. Plates were washed 4 times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and blocked in PBS containing 1% BSA for 1 h. Serum from each animal was serially diluted in 2-fold increments, and 100 μl of each was added to the plate in triplicate. After incubation at 4°C overnight, the plate was washed and HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Sigma) added for 2 h at room temperature. Wells were washed and 100 μl of o-phenylenediamine (0.4 mg/ml, Sigma) added to each well. After 15 min, optical densities were read at 450 nm on a microplate reader. Fifty percent endpoint titers were calculated according to the method of Reed and Muench (42).

Anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibody assay.

Serum was heat inactivated at 56°C for 30 min. Each sample was serially diluted in serum-free DMEM in 2-fold increments starting from a 1:20 dilution as described previously (12). Each dilution (100 μl) was mixed with 1 × 106 PFU of AdlacZ, incubated for 1 h at 37°C, and then added to HeLa cells (CCL-2; ATCC) seeded in 96-well plates (2 × 104 cells/well). One hundred microliters of DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS was added to each well after 1 h. Beta-galactosidase expression was assessed 24 h later. Neutralizing antibody titers were calculated as the dilution at which beta-galactosidase expression is reduced by 50% using the Reed and Muench method (42).

Evaluation of virus distribution, gene expression, and toxicity.

Beta-galactosidase expression was assessed in tissue samples by histochemical staining as described previously (11). The number of virus genomes in tissue was determined by real-time PCR of genomic DNA extracts as described previously (7). Serum cytokines were assessed by ELISA (Invitrogen, BioSource International, Camarillo, CA). Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were measured as described previously (7). Platelet counts were performed at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Keeling Center for Comparative Medicine and Research, Bastrop, TX.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed for statistical significance by performing a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) between control and experimental groups, followed by Bonferroni-Dunn post hoc tests when appropriate. Analysis was performed with SigmaStat software (Systat Software, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

In vitro characterization of virus-antibody complexes.

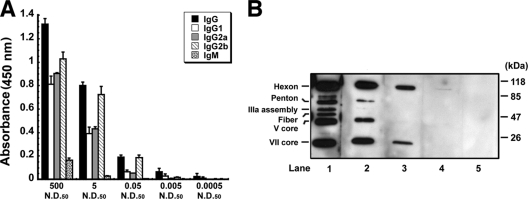

In an initial pilot study, freshly purified virus containing the beta-galactosidase transgene at a concentration of 1.0 × 1011 virus particles/ml was mixed with mouse-generated anti-adenovirus antibody at concentrations 500, 5, and 0.05 times the 50% neutralizing dose (ND50) of the stock solution. The antibody stock mostly consisted of anti-adenovirus IgG antibodies, with Ig2b being the primary isotype (Fig. 2A). Although a marked amount of IgM antibodies was also found in the 500-ND50 preparation, this isotype could not be detected in the 5- and 0.05-ND50 formulations. Western blotting revealed that the antibodies were capable of binding major adenovirus capsid proteins (hexon, penton, fiber) in preparations with concentrations at and above 5 ND50 (lane 1, Fig. 2B). The 0.05-ND50 preparation bound hexon alone (lane 3, Fig. 2B). Addition of antibody at the 500-ND50 level reduced the infectious titer of the virus by a factor of 4,000 (Table 1). The infectious titer of the 5-ND50 preparation was somewhat lower than that of the 500-ND50 preparation (1.60 ± 0.55 × 108 versus 1.02 ± 0.52 × 108 infectious virus particles/ml) while the titer of the 0.05-ND50 preparation was approximately twice that amount (2.30 ± 0.55 × 108).

Fig 2.

Characterization of stock serum by ELISA isotyping (A) and Western blotting (B). (A) Isotyping assays revealed that the antibody stock used to create antibody-virus complexes mostly consisted of anti-adenovirus IgG antibodies with Ig2b being the primary isotype in the 500-, 5-, and 0.05-ND50 preparations. Marked amounts of IgM antibodies were detected in the 500-ND50 preparation only. Values for isotypes present in the 0.005- and 0.0005-ND50 preparations fell below the detection limit of the assay. Error bars indicate the standard deviations from the average results of 4 separate preparations for each serum concentration. (B) Western blot of adenovirus capsid proteins resolved on a 9% SDS-PAGE gel. Each lane was incubated with a different dilution of stock serum. Lane 1, 5 ND50; lane 2, 0.5 ND50; lane 3, 0.05 ND50; lane 4, 0.005 ND50; lane 5, 0.0005 ND50. Serum concentrations at or above 5 ND50 bound the primary adenovirus capsid proteins (hexon, penton, fiber). Fiber binding was lost at the 0.5-ND50 concentration. Hexon binding was detected in the 0.05- and 0.005-ND50 preparations. Binding of adenovirus capsid proteins could not be detected at the 0.0005-ND50 concentration.

Table 1.

Infectious titer as determined by two in vitro assays for each production lot of virus-antibody complexesa

| Treatment | ITA (ivp/ml) | PLA (PFU/ml) | PFU:IVP ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus alone | 4.08 ± 0.22 × 1010 | 4.5 ± 0.48 × 1010 | 1:1.1 |

| Virus + 500 ND50 | 1.02 ± 0.52 × 108 | 3.2 ± 0.95 × 106 | 1:32 |

| Virus + 5 ND50 | 1.60 ± 0.55 × 108 | 3.6 ± 0.28 × 106 | 1:44 |

| Virus + 0.05 ND50 | 2.30 ± 0.92 × 108 | 4.2 ± 0.73 × 106 | 1:55 |

| Virus + 0.005 ND50 | 2.53 ± 0.22 × 1010 | NA | |

| Virus + 0.0005 ND50 | 3.62 ± 0.15 × 1010 | NA |

The input for each of these preparations was 1.0 × 1011 virus particles/ml, as determined by measuring the absorbance of each preparation at 260 nm. ITA, infectious titer assay; ivp, infectious virus particles; PLA, plaque assay; NA, not assayed.

In vivo performance of virus-antibody complexes. Transgene expression.

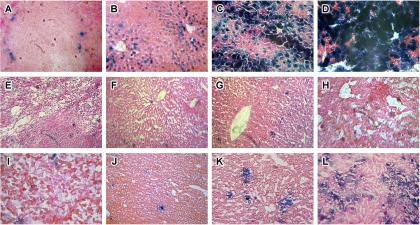

Systemic administration of recombinant adenoviruses containing beta-galactosidase elicit measurable levels of transgene expression in the marginal zones of the spleen (Fig. 3A) and the liver (Fig. 3B) as early as 6 h after administration. Transgene expression in the liver intensifies by day 4 (Fig. 3C) and peaks by day 7 (Fig. 3D). Transgene expression could not be detected in the spleens (Fig. 3E) or the livers of animals given the 500-ND50 preparation at any of the selected time points (Fig. 3F to H). Similar results were obtained for the 5-ND50 preparation (data not shown). Spotty transgene expression was detected in the spleens of mice given the 0.05-ND50 preparation (Fig. 3I). Although notable transgene expression could not be detected in the livers of these animals at 6 h (Fig. 3J), some expression could be detected at 4 days (Fig. 3K), which intensified by day 7 (Fig. 3L) but was still significantly less than that observed in mice given virus alone (Fig. 3D).

Fig 3.

VACs elicit limited transgene expression after systemic administration. First-generation adenoviral vectors were mixed with various concentrations of mouse anti-adenovirus antibodies and given to C57BL/6 mice by tail vein injection (1 × 1011 particles/ml). Animals were sacrificed and livers were evaluated for beta-galactosidase expression by histochemical staining 6 h (second column), 4 days (third column), and 7 days (fourth column) after administration. Samples obtained from the spleen were also evaluated for transgene expression at the 6-h time point (first column). Transgene expression could not be detected in any samples from mice given the 500-ND50 preparation (E to H). Similar results were found for the 5-ND50 preparation (data not shown). Transgene expression could be detected in sections obtained from animals given the 0.05-ND50 preparation (I to L), and the level was significantly lower than that for mice given the virus alone at all time points (A to D).

Immune response.

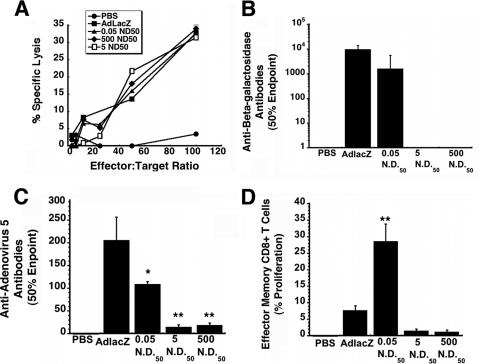

The T cell response was first evaluated by 51Cr release assays using splenocytes of mice given either the native virus or VACs. After incubation with H-2b target cells infected with native virus expressing beta-galactosidase, substantial cytolysis was detected in samples from animals given unmodified virus (AdlacZ; Fig. 4A). Formation of virus-antibody complexes did not blunt the CTL response, as significant cytolysis was detected in samples from all groups given these preparations. Negligible cytolysis was observed with naïve, restimulated splenocytes (PBS).

Fig 4.

VACs at a concentration of 0.05 ND50 can elicit strong T-cell mediated and humoral immune responses against an encoded transgene. (A) CTL responses elicited by VACs. Splenocytes harvested 10 days after treatment were restimulated in vitro for 5 days and tested for specific lysis on MC57 target cells infected with adenovirus expressing beta-galactosidase in a 6-h 51Cr release assay. Percent specific lysis is expressed as a function of different effector-to-target ratios (6:1, 12.5:1, 25:1, 50:1, and 100:1). (B) Anti-beta-galactosidase neutralizing antibody profile after a single dose of VACs in C57BL/6 mice. Serum was analyzed 28 days after treatment for the presence of antibody to beta-galactosidase. Fifty percent endpoint titers were calculated according to the method of Reed and Muench. (C) Anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibody levels. The presence of neutralizing antibody against the adenoviral vector was determined by assessing the ability of collected sera to block infection of HeLa cells by virus expressing beta-galactosidase. The 50% endpoint titer is plotted according to treatment. (D) Memory response. Splenocytes were isolated 42 days after treatment, stained with CFSE, and stimulated with beta-galactosidase-specific peptide for 5 days. Cells positive for CD8+, CD44hi, and CD62Llo were evaluated for CFSE staining by flow cytometry. Data represent the degree of effector CD8 T cell expansion after stimulation. Data illustrated in each panel reflect the means and standard deviations of results for five animals per group. Statistical significance was determined between individual treatment groups and vehicle controls by one-way analysis of variance with a Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc test. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

In an effort to evaluate the ability of virus-antibody complexes to strengthen the B cell-mediated immune response against antigens encoded in adenovirus-based vaccines, serum was collected and screened for anti-beta-galactosidase antibodies on day 28. The most significant amount of antibody was found in animals given virus alone (9,606 ± 624 50% endpoint titer; Fig. 4B). Titers were somewhat lower in animals receiving the 0.05-ND50 preparation (1,580 ± 775 50% endpoint titer). Trace amounts of anti-beta-galactosidase antibodies were detected in samples from mice given the 500- and 5-ND50 preparations. Small amounts of anti-adenovirus NABs were also detected in these groups (18.2 ± 5.5 and 13.7 ± 6.12 50% endpoint titers, respectively; Fig. 4C). The amount of anti-adenovirus NABs present in animals given the 0.05-ND50 preparation were significantly lower than that of animals given the virus alone (108.5 ± 6.36 versus 205.0 ± 51.3 50% endpoint titer, P ≤ 0.05).

CD8 T cell memory is a crucial component of protective immunity against various pathogens. In this context, beta-galactosidase-specific T cells were evaluated for their ability to rapidly proliferate when pulsed with immunostimulatory peptides from the cognate antigen. Five days after restimulation, an average of 28.6 ± 5.2% of effector memory CD8+ T cells obtained from mice given the 0.05-ND50 preparation had undergone proliferation in response to the antigenic epitope (Fig. 4D). This was significantly higher than that of mice given virus alone (7.7 ± 1.4%, P ≤ 0.01) and the other virus-antibody preparations (1.2 ± 0.5% and 1.5 ± 0.5%, 500 and 5 ND50, respectively).

Toxicity profiles of virus-antibody complexes.

The immune response against capsid proteins is largely responsible for the toxicity associated with systemic administration of recombinant adenoviral vectors (46). Thus, several biochemical markers were measured over time to delineate the toxicity profiles of virus-antibody complexes.

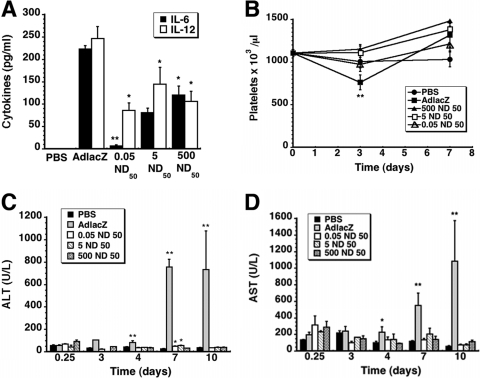

Proinflammatory cytokines.

Serum was collected 6 h after treatment and analyzed for IL-6 and IL-12, markers commonly associated with activation of the innate immune response against recombinant adenoviruses (2). This time point was selected because cytokine concentrations peak approximately 6 h after virus infection and rapidly decline within 24 h (20). Samples from animals given virus alone contained the highest concentrations of both cytokines (223.4 ± 7.6 pg/ml IL-6, 246.3 ± 26.8 pg/ml IL-12; Fig. 5A). The 500-ND50 preparation reduced IL-6 by a factor of 2, while samples from mice given the 0.05-ND50 preparation contained the lowest levels of this cytokine (6.5 ± 2.8 pg/ml, P ≤ 0.01). IL-12 was also significantly lower in this treatment group with respect to mice given virus alone (86.1 ± 16.9 pg/ml, P ≤ 0.05). A similar trend was also noted for the 500- and 5-ND50 preparations (106.02 ± 22.8 pg/ml and 144.2 ± 37.8, respectively; P ≤ 0.05).

Fig 5.

VACs significantly reduce virus-induced toxicity. (A) Serum cytokine levels. IL-6 and IL-12 (p70) were assessed 6 h after systemic administration of a single dose of either virus alone (1 × 1011 virus particles), the same dose of virus mixed with different amounts of anti-adenovirus antibody, or saline (PBS). (B) Platelets. Fourteen days before treatment, baseline platelet counts were determined (t = 0). A notable drop in platelet count was observed only in animals given virus alone. (C) Kinetic profile of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Normal levels for C57BL/6 mice fall within the range of 24 to 140 U/liter (40). (D) Kinetic profile of serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST). Normal levels for C57BL/6 mice fall within the range of 72 to 288 U/liter (40). In each panel, data reflect average values ± the standard error of the mean for 5 mice from each treatment group. Statistical significance was determined between individual treatment groups and vehicle controls by one-way analysis of variance with a Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc test. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

Platelets.

Baseline platelet counts for mice used in these studies was 1,105.1 ± 41.6 × 103/μl (Fig. 5B). Three days after treatment, a significant drop to 762.5 ± 86.3 × 103/μl was detected in animals given virus alone (P = 0.001). This returned to baseline 4 days later. Platelet counts from mice given the 5- and 0.05-ND50 preparations (1,110.0 ± 83.5 and 1,105.1 ± 41.6 × 103/μl, respectively) were not statistically different than those from animals given saline (PBS, 1,007.5 ± 74.5 × 103/μl, P = 0.07) and remained unchanged throughout the study. Similar results were obtained for animals given the 500-ND50 preparation.

Serum transaminases.

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were used to monitor hepatotoxicity associated with systemic administration of adenovirus (Fig. 5C and D). Animals given virus alone experienced significant elevations in serum AST at days 4, 7, and 10 after treatment with respect to saline controls (2, 29, and 20 times baseline, respectively; P = 0.001) (Fig. 5D). AST levels of mice given any of the virus-antibody combinations all fell within the accepted normal range for C57BL/6 mice throughout the study (40). A similar trend was observed for ALT; however, transaminase levels of animals given the 5- and 0.05-ND50 preparations were notably higher than baseline levels 7 days after treatment (55.2 ± 4.6 and 49.8 ± 3.2 U/liter, respectively, versus 26.6 ± 1.9 U/liter PBS; P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 5C).

Refinement and selection of additional virus-antibody ratios for further investigation in naïve mice and those with preexisting immunity.

Critical evaluation of data identified the 0.05-ND50 antibody concentration as the one that most closely fit our criteria for a suitable vaccine candidate, since it elicited the strongest T and B cell responses to the transgene and minimized virus-associated toxicity. Although the 500- and 5-ND50 preparations prevented notable transgene expression in any of the organs screened by histochemical staining and ELISA (data not shown), moderate levels of transgene expression in organs of animals given the 0.05-ND50 preparation suggested that this may not be the true optimum and that another antibody-virus ratio may further improve the transgene-specific immune response. In this regard, two additional virus-antibody concentrations were selected (0.005 and 0.0005 ND50) for toxicological and immunological comparison with virus alone in naïve mice and those with preexisting immunity to adenovirus.

Effect of reducing the amount of anti-adenovirus antibody on the immune response against the transgene.

The transduction efficiency of preparations made with the revised antibody concentrations was similar to free virus in vitro and in vivo. The infectious titer of the 0.005-ND50 preparation was reduced by only a factor of 2, while that of the 0.0005-ND50 preparation was not significantly different from that of virus alone (Table 1). Although Western blotting revealed that the 0.005-ND50 preparation bound hexon (lane 4, Fig. 2B), protein binding could not be detected with the 0.0005-ND50 dilution (lane 5, Fig. 2B). Visual inspection of sections of spleen and liver histochemically stained for beta-galactosidase also revealed that each of these preparations transduced these organs in a manner similar to that of virus alone (data not shown).

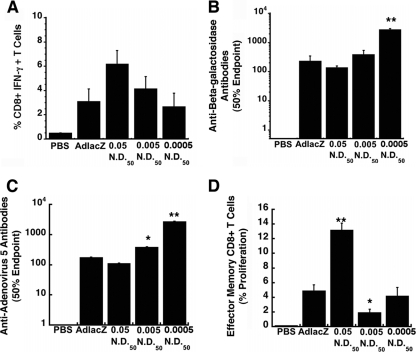

Peptide-specific activation of CD8+ T cells, evaluated by the production of IFN-γ, was detected in splenocytes of mice given the 0.005- and 0.0005-ND50 preparations at frequencies of 4.2 ± 1 and 2.7 ± 1.1%, respectively (Fig. 6A). These values were not statistically different from those of mice given virus alone (3.1 ± 1.0%, P = 0.06). The frequency of IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells in mice given the 0.05-ND50 preparation was twice this value (6.2 ± 1.1%). There was no significant difference in the amount of anti-beta-galactosidase antibody in serum from animals given either the 0.005-ND50 preparation (383 ± 150) or virus alone (226 ± 116 50% endpoint titer; P = 0.07) (Fig. 6B). A significant increase in anti-transgene antibodies was noted for animals given the 0.0005-ND50 preparation (2,698 ± 337 50% endpoint titer). Antibody titers of the 0.05-ND50 group were slightly lower than those of the group given virus alone (134.5 ± 22.2). Samples from animals given the 0.05-ND50 preparation also contained anti-adenovirus antibodies at a concentration not significantly different from mice given virus alone (108.5 ± 30.5 and 175.1 ± 47.5 50% endpoint titer, respectively; P = 0.06) (Fig. 6C). In contrast, anti-adenovirus antibody levels were significantly elevated in samples from the 0.005-ND50 (383 ± 98 50% endpoint titer; P ≤ 0.05) and the 0.0005-ND50 (2,691 ± 624 50% endpoint titer; P ≤ 0.01) groups. Significant proliferation of beta-galactosidase-specific effector memory CD8+ T cells was detected in mice given the 0.05-ND50 preparation (13.2% ± 1%) with respect to mice given virus alone (4.9 ± 0.8%; P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 6D). The memory response was significantly reduced to 1.9 ± 0.5% in mice given the 0.005-ND50 preparation (P ≤ 0.05), while that of animals given virus with antibody at a concentration of 0.0005 ND50 was not significantly different from that of mice given virus alone (4.2 ± 1.2%; P = 0.06).

Fig 6.

Anti-adenovirus antibody at a concentration of 0.05 ND50 facilitates strong effector memory responses against an encoded transgene in naive mice. (A) Frequency of IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells. Naïve mice were given either virus alone (1 × 1011 virus particles), the same amount of virus mixed with different concentrations of anti-adenovirus antibody, or saline (PBS, negative control) systemically. Ten days later, 1 × 106 splenocytes from each animal were incubated with a beta-galactosidase-specific peptide and responsive cells analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Anti-beta-galactosidase neutralizing antibody profile. Serum was analyzed 28 days after treatment by ELISA. Fifty percent endpoint titers were calculated according to the method of Reed and Muench. (C) Anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibody. NAB titers were determined by assessing the ability of collected sera to block infection of HeLa cells by adenovirus expressing beta-galactosidase. The 50% endpoint titer is plotted according to treatment. (D) Memory response. Splenocytes were isolated 42 days after treatment, stained with CFSE, and stimulated with beta-galactosidase-specific peptide. CD8+ cells also positive for CD44hi and CD62Llo were evaluated for CFSE staining by flow cytometry. Data illustrated in each panel reflects the means and standard errors of the means for five animals per group. Statistical significance was determined between individual treatment groups by one-way analysis of variance with a Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc test. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

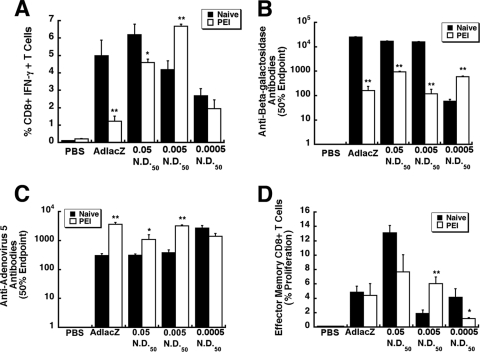

Effect of preexisting immunity to adenovirus on the in vivo performance of VACs.

PEI significantly compromised the production of beta-galactosidase-specific IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells in mice given virus alone (5.0 ± 0.9% [naïve] versus 1.23% [PEI]; P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 7A). Although PEI did reduce the number of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells in mice given the 0.05-ND50 preparation from 6.2 ± 0.6 to 4.6 ± 0.2%, the latter value was still 4 times that for mice given virus alone. Prior exposure to adenovirus did not affect the transgene-specific T cell response in mice given the 0.0005-ND50 preparation (2.70 ± 0.4% [naïve] versus 1.96% ± 0.5% [PEI]) and significantly improved the response of mice given the 0.005-ND50 formulation (4.20 ± 0.5% [naïve] versus 6.70% ± 0.1% [PEI]; P ≤ 0.01).

Fig 7.

Preexisting immunity to adenovirus serotype 5 does not significantly compromise the immune response elicited by some VACs. Preexisting immunity was established by intramuscular injection of 1 × 1011 particles of AdEGFP 28 days prior to administration of VACs. At that time, mice had a circulating anti-adenovirus NAB titer of a 184.2 ± 32.4 reciprocal dilution. Animals given saline served as negative controls (PBS). (A) Frequency of IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells. Ten days after treatment, 1 × 106 splenocytes from each animal were harvested and incubated with a beta-galactosidase-specific peptide. Responsive cells were quantitated by flow cytometry. (B) Anti-beta-galactosidase antibody profile after administration of VACs. Serum was analyzed 28 days after treatment. Fifty percent endpoint titers are plotted according to treatment and were calculated according to the method of Reed and Muench. (C) Anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibody. Neutralizing antibody titers were determined by assessing the ability of sera to block infection of HeLa cells by unmodified virus expressing beta-galactosidase. The 50% endpoint titer is plotted according to treatment. (D) Memory response. Cells positive for CD8+, CD44hi, and CD62Llo were evaluated for CFSE staining by flow cytometry. Data represent the degree of effector CD8+ T cell expansion after stimulation for each treatment group. Data illustrated in each panel reflect the means and standard errors of the means for five animals/group. Statistical significance was determined between individual treatment groups and vehicle controls or between naïve animals and those with preexisting immunity to adenovirus by one-way analysis of variance with a Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc test. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01. PEI, preexisting immunity to adenovirus.

PEI significantly reduced the amount of circulating anti-beta-galactosidase antibodies in mice given virus alone by a factor of 150 (25,542 ± 748 [naïve] versus 163.3 ± 79.7 [PEI] 50% endpoint titer, Fig. 7B). A similar trend was noted for the 0.005-ND50 preparation (16,306 ± 202.86 [naïve] versus 121.1 ± 59.9 [PEI] 50% endpoint titer). PEI also reduced the number of circulating anti-beta-galactosidase antibodies in mice given the 0.05-ND50 preparation but to a lesser degree (17,382.3 ± 445 [naïve] to 955 ± 53.5 [PEI] 50% endpoint titer). Antibody titers in mice given the 0.0005-ND50 preparation increased under these conditions from 60.3 ± 10.9 (naïve) to 600.5 ± 44.7 (PEI) 50% endpoint titer. This specific preparation also induced production of anti-adenovirus antibodies in naïve mice to a level that was approximately 9 times that of mice given virus alone (Fig. 7C). Preexisting immunity did not significantly alter the amount of antibodies produced against the virus in this group (2,691 ± 624 [naïve], 1,415 ± 660 [PEI] 50% endpoint titer, P = 0.056). PEI boosted the amount of anti-adenovirus antibodies produced by mice given the 0.005-ND50 and 0.05-ND50 preparations by factors of 9 and 4, respectively. The highest increase in antibody production was noted, however, in mice given virus alone (308 ± 47.5 [naïve], 3,704 ± 613 [PEI] 50% endpoint titer).

The memory response of mice given virus alone was not compromised by PEI, since 4.9 ± 0.8% effector memory cells from this group responded to the transgene-specific peptide and 4.4 ± 1.7% from those with PEI responded in the same manner (P = 0.72; Fig. 7D). The memory response was significantly reduced in mice given the 0.0005-ND50 preparation (4.17 ± 1.2% [naïve] versus 1.2 ± 0.1 [PEI]; P ≤ 0.01). A less significant reduction was noted with the 0.05-ND50 preparation (13.2 ± 1.0% [naïve] versus 7.7 ± 2.4 [PEI]; P ≤ 0.05). In contrast, PEI increased the memory response elicited by the 0.005-ND50 preparation 3-fold from 1.9 ± 0.5% proliferating effector cells (naïve) to 6.0 ± 1.0% (PEI).

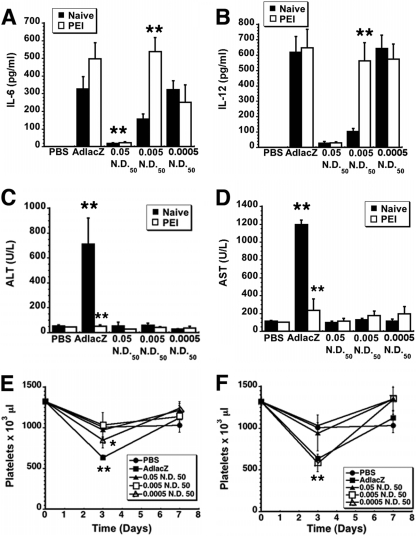

Cytokine secretion patterns and clinical chemistry profiles of optimized virus-antibody complexes.

PEI increased serum IL-6 and IL-12 in mice given the 0.005-ND50 preparation 3.5 and 5.4 times baseline, respectively (P ≤ 0.01; Fig. 8A and 8B). In contrast, PEI did not significantly alter cytokine levels of mice treated with virus alone and the 0.0005-ND50 preparation (P ≥ 0.05). Samples from mice given the 0.05-ND50 formulation contained the smallest amount of both IL-6 (17.6 ± 4.7 [naïve] versus 21.8 ± 6.5 [PEI] pg/ml) and IL-12 (27.6 ± 9.4 [naïve] versus 28.8 ± 6.3 [PEI] pg/ml). Evaluation of serum transaminases 7 days after administration of virus alone revealed that PEI significantly reduced both ALT (709.5 [naïve] versus 51.4 U/liter [PEI]) and AST (1,192.5 [naïve] versus 232.2 U/liter [PEI]; P ≤ 0.01; Fig. 8C and 8D). Serum transaminases fell within normal ranges for mice in the other treatment groups throughout the course of the study. Although a significant drop in platelets was noted for naïve mice given either virus alone or the 0.0005-ND50 preparation (Fig. 8E), this effect was absent in mice with PEI given the 0.0005-ND50 preparation (Fig. 8F). Platelets dropped from baseline (1,322 × 103/μl) to 582.5 × 103/μl in mice with PEI given the 0.005-ND50 preparation (P ≤ 0.01; Fig. 8F). Thrombocytopenia was not observed in naïve mice or those with PEI given the 0.05-ND50 preparation.

Fig 8.

VACs at a 0.05-ND50 ratio significantly reduce the cytokine response and virus-induced thromobcytopenia in mice with PEI. (A) IL-6 secretion. IL-6 was assessed in serum collected 6 h after systemic administration of either virus alone (AdlacZ), virus mixed with different concentrations of anti-adenovirus antibody, or saline (PBS). (B) IL-12 secretion. IL-12 (p70) was also measured 6 h after treatment from a minimum of five mice per group. (C) Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT). ALT was measured at the time when significant increases are commonly noted in mice given virus alone, 7 days after treatment. Normal levels for C57BL/6 mice are 24 to 140 U/liter (40). (D) Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST). AST was also measured at the time when significant increases are commonly noted in mice given virus alone, the 7-day time point. AST levels normally fall within the 72- to 288-U/liter range (40). (E) Kinetic profile of platelet counts for naïve mice. Fourteen days before treatment, baseline platelet counts were determined (t = 0). Notable thrombocytopenia was detected in animals given virus alone and the 0.0005-ND50 preparation. (F) Kinetic profile of platelet counts for mice with PEI. Platelet counts were significantly reduced in mice 3 days after virus to establish PEI was given, with levels returning to baseline prior to administration of VACs 28 days later (data not shown). In each panel, statistical significance was determined either between individual treatment groups and vehicle controls or between naïve animals and those with preexisting immunity to adenovirus by one-way analysis of variance with a Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc test. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The experiments described in this paper were primarily designed to determine if virus-antibody complexes can be optimized to effectively influence the strength and type of immune response elicited by a recombinant adenovirus. While this certainly is not the first report describing a strategy for targeting Fcγ receptors on antigen-presenting cells to improve the potency of vaccine candidates (14, 18, 39), it is the first, to our knowledge, that makes a concerted effort to identify specific virus:antibody ratios that strengthen the immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus. Data obtained from our initial pilot study revealed that the immune response against an encoded transgene could be enhanced by virus-antibody complexes and the degree of enhancement is ratio dependent. The absence of transgene expression in tissues isolated from mice given the 500- and 5-ND50 preparations and data from infectious titer assays illustrate that, at these concentrations, the antibody stock could effectively neutralize the virus in vitro and in vivo. Although these preparations elicited strong, short-term T cell responses in naïve mice, a measurable humoral response against the transgene was not established (Fig. 4). In contrast, the same amount of virus mixed with antibody at a concentration of 0.05 ND50 could induce both cellular and humoral responses, similar to the virus alone with moderate amounts of transgene expression noted in target tissues (Fig. 3). This suggests that (i) a robust immune response to an encoded transgene requires some balance between direct uptake and processing of virus particles by antigen-presenting cells and effective transduction of target cells and tissues in the whole animal and (ii) that these complexes could be used to incite tailored immune responses for particular disease targets.

Physical characterization of virus-antibody complexes by dynamic light scattering revealed that over 90% of the particles present in the 500-ND50 preparation had average hydrodynamic radii of 3,862 nm and 76% of the 5-ND50 preparation contained particles of similar size. Characterization of antibody isotypes in the stock serum used to generate the complexes suggests that anti-adenovirus IgM antibodies facilitated aggregation of virus particles in these preparations (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the 0.05-ND50 preparation consisted primarily of particles with radii similar to that of a single adenovirus particle (83.4 ± 12.9 nm). Large particles (≥1 μm) are toxic to antigen-presenting cells and can induce spontaneous apoptosis or necrosis accompanied by the release of proinflammatory cytokines (33, 48). This also has been described for adenovirus infection with the rapid destruction of Kupffer cells noted immediately after systemic administration of large amounts of virus (26, 30, 55). Thus, we believe the initial strong T cell-mediated immune response generated by these preparations was partly in response to spontaneous destruction of antigen-presenting cells. Opsonization of virus particles through the complement system was most likely responsible for the low levels of anti-adenovirus antibodies and effector memory T cells found in mice given these preparations.

Data generated with preparations in the 0.05 to 0.0005-ND50 range also suggest that the amount of neutralizing antibody present in a virus-antibody complex can influence the type and quality of immune response elicited against a transgene cassette. Administration of virus mixed with the antibody at a concentration of 0.05 ND50 favored the T cell-mediated response (Fig. 4 and 6). This was most likely achieved by reinforcement of the early T cell response initiated by free virions through preferential activation of macrophages and dendritic cells by virus-antibody complexes, resulting in a significant increase in transgene-specific memory effector cells (31, 36, 60). Although the 0.005- and 0.0005-ND50 combinations did not improve the transgene-specific cellular or humoral immune responses with respect to the virus alone in naïve animals (Fig. 6), they did strengthen certain arms of the immune response in mice with preexisting immunity (Fig. 7). For example, cytokine secretion was significantly increased by the 0.005-ND50 formulation in mice with preexisting immunity (Fig. 8). This effect, in concert with this specific virus-antibody ratio, fostered strong cellular responses in the form of increased numbers of transgene-specific IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells and effector memory cells higher than those elicited by virus alone under the same conditions (Fig. 7). Although cytokine secretion was not enhanced by preexisting immunity in animals given the 0.0005-ND50 preparation, this combination was sufficient to improve the humoral response against beta-galactosidase without significantly increasing the response to the virus capsid (Fig. 7). This may be due to the ability of this combination to target virus to different cellular compartments and sufficiently alter antigen trafficking and processing in a manner that facilitates this arm of the immune response (25, 59). In order to define the limits to which one arm of the immune response can be influenced by virus-antibody complexes, additional studies within narrower antibody concentration ranges are under way in our laboratories.

A critical issue to the development of adenovirus-based vaccines is the reliability of in vitro neutralization assays to predict the effect of anti-virus antibodies on the in vivo performance of the vector (9, 37, 38). In this context, it is important to realize that the extent to which serum can effectively neutralize virus infection is determined by several factors. The presence (or absence) of particular antibody isotypes and their respective affinity for antigenic epitopes on the virus can significantly effect the neutralization properties of serum. The number and identity of antigenic epitopes against which antibodies are generated, the concentration of nonimmune components that promote virus infection (clotting factors), and the presence/absence of virus-specific and Fc receptors on the cell line used in testing serum also influence the results of neutralizing assays and the ability to predict the performance of adenoviruses in vivo (35, 38). Characterization of our stock serum revealed that multivalent IgM antibodies as well as IgG antibodies capable of binding all major virus capsid proteins were present in preparations in which large aggregates of virus particles were detected (Fig. 2). This provides a valid explanation for the immunological responses elicited by complexes formed with high concentrations of antibody stock and also demonstrates the role that antibody isotype and specificity plays in the immune response against the adenovirus and its encoded antigen. IgG2b antibodies were the most abundant isotype in each dilution used in the studies outlined in this paper (Fig. 2A). Of all the IgG subclasses, this isotype has the lowest affinity for Fc receptors on phagocytic cells and only binds to one Fcγ receptor, FcγR II (45). Engagement of the two isoforms of this receptor, FcγR IIA and FcγR IIB, can have opposing effects, with FcγR IIA eliciting a stimulatory signal and FcγR IIB inhibiting immune activation. Taken together, these two effects may be responsible for the variability in the immune responses elicited in vivo by preparations containing the lowest antibody concentrations, which could not be predicted using standard in vitro neutralization assays. Most recently, Perreau et al., using an antibody stock preparation with a composition similar to ours, demonstrated that FcγR IIA receptors do play a key role in antibody-mediated immune responses against adenoviral vectors (36).

Certain antibody isotypes have also been shown to mediate platelet clearance in a differential manner, which could explain why the toxicity profiles of the virus-antibody complexes was significantly lower than that of virus alone (29) (Fig. 8). In contrast to most adenovirus-based vaccines to date, the vector used to generate the data described in this paper contained a nonsecreted transgene (24). Additional studies with an immunologically relevant transgene cassette to assess the immune response in the context of protective immunity after antigenic challenge will further establish the clinical utility of virus-antibody complexes for vaccination purposes. The fact that most of the virus-antibody preparations tested strengthened the humoral immune response to adenovirus in mice with established preexisting immunity suggests that systemic administration of this type preparation is not yet a viable therapeutic option in this particular patient population. Additional evaluation of this approach in naïve animals and models of preexisting immunity with well-characterized lots of monoclonal antibodies will be the focus of future studies.

To our knowledge this is the first report describing the immunological profile of a defined series of antibody:adenovirus combinations in both naïve mice and those with preexisting immunity. Although correlations between anti-adenovirus cellular immune responses and neutralizing antibody titers in the clinic have been described (4, 10), this concept has not been extensively investigated in the context of the transgene-specific response in preclinical animal models as described in these studies. Subtle changes in the type of immune response elicited against the transgene by complexes formed with very low antibody concentrations suggest that information generated from studies such as this would be useful in the assessment of clinical candidates for which a particular immune response is desired. Additional work in larger animal models with paired evaluation of clinical data is also warranted, not only to determine if this would be of benefit in the optimization of vaccination protocols but also to determine when and if these complexes may establish conditions that are inappropriate for certain antigens and disease states.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Leah Donaldson, Sandra Renteria, and Gavin Best for excellent technical support in conducting the studies outlined in this paper.

This work was supported by a research grant awarded to the corresponding author by Immunobiosciences, Inc.

Author disclosure statement: although this work was supported by a research grant awarded to the corresponding author by Immunobiosciences, Inc., neither she nor any member of her research team held any equity or other financial stake in this company during the project or after its completion.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Appledorn DM, et al. 2008. Complex interactions with several arms of the complement system dictate innate and humoral immunity to adenoviral vectors. Gene Ther. 15: 1606–1617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Appledorn DM, et al. 2008. Adenovirus vector-induced innate inflammatory mediators, MAPK signaling, as well as adaptive immune responses are dependent upon both TLR2 and TLR9 in vivo. J. Immunol. 181: 2134–2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baker AH, McVey JH, Waddington SN, Di Paolo NC, Shayakhmetov DM. 2007. The influence of blood on in vivo adenovirus bio-distribution and transduction. Mol. Ther. 15: 1410–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Benlahrech A, et al. 2009. Adenovirus vector vaccination induces expansion of memory CD4 T cells with a mucosal homing phenotype that are readily susceptible to HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106: 19940–19945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boquet MP, Wonganan P, Dekker JD, Croyle MA. 2008. Influence of method of systemic administration of adenovirus on virus-mediated toxicity: focus on mortality, virus distribution, and drug metabolism. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 58: 222–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boyer J, et al. 2010. Protective immunity against a lethal respiratory Yersinia pestis challenge induced by V antigen or the F1 capsular antigen incorporated into the adenovirus capsid. Hum. Gene Ther. 21: 891–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Callahan SM, Boquet MP, Ming X, Brunner LJ, Croyle MA. 2006. Impact of transgene expression on drug metabolism following systemic adenoviral vector administration. J. Gene Med. 8: 566–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Callahan SM, et al. 2008. Controlled inactivation of recombinant viruses with vitamin B2. J. Virol. Methods 148: 132–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng C, et al. 2010. Differential specificity and immunogenicity of adenovirus type 5 neutralizing antibodies elicited by natural infection or immunization. J. Virol. 84: 630–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chirmule N, et al. 1999. Immune responses to adenovirus and adeno-associated virus in humans. Gene Ther. 6: 1574–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Croyle MA, Chirmule N, Zhang Y, Wilson JM. 2002. PEGylation of E1-deleted adenovirus vectors allows significant gene expression on readministration to liver. Hum. Gene Ther. 13: 1887–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Croyle MA, Chirmule N, Zhang Y, Wilson JM. 2001. “Stealth” adenoviruses blunt cell-mediated and humoral immune responses against the virus and allow for significant gene expression upon readministration in the lung. J. Virol. 75: 4792–4801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Croyle MA, Roessler BJ, Davidson BL, Hilfinger JM, Amidon GL. 1998. Factors that influence stability of recombinant adenoviral preparations for human gene therapy. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 3: 373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deckert PM. 2009. Current constructs and targets in clinical development for antibody-based cancer therapy. Curr. Drug Targets 10: 158–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Descamps D, Benihoud K. 2009. Two key challenges for effective adenovirus-mediated liver gene therapy: innate immune responses and hepatocyte-specific transduction. Curr. Gene Ther. 9: 115–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dharmapuri S, Peruzzi D, Aurisicchio L. 2009. Engineered adenovirus serotypes for overcoming anti-vector immunity. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 9: 1279–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Geisbert TW, et al. 2011. Recombinant adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) and Ad35 vaccine vectors bypass immunity to Ad5 and protect nonhuman primates against ebolavirus challenge. J. Virol. 85: 4222–4233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gosselin EJ, Bitsaktsis C, Li Y, Iglesias BV. 2009. Fc receptor-targeted mucosal vaccination as a novel strategy for the generation of enhanced immunity against mucosal and non-mucosal pathogens. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz.) 57: 311–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Graham FL, van der Eb AJ. 1973. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology 52: 456–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hartman ZC, Appledorn DM, Amalfitano A. 2008. Adenovirus vector induced innate immune responses: impact upon efficacy and toxicity in gene therapy and vaccine applications. Virus Res. 132: 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jager L, Ehrhardt A. 2007. Emerging adenoviral vectors for stable correction of genetic disorders. Curr. Gene Ther. 7: 272–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jooss K, Ertl HC, Wilson JM. 1998. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte target proteins and their major histocompatibility complex class I restriction in response to adenovirus vectors delivered to mouse liver. J. Virol. 72: 2945–2954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kreppel F, Kochanek S. 2008. Modification of adenovirus gene transfer vectors with synthetic polymers: a scientific review and technical guide. Mol. Ther. 16: 16–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lasaro MO, Ertl HC. 2009. New insights on adenovirus as vaccine vectors. Mol. Ther. 17: 1333–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leopold PL, Wendland RL, Vincent T, Crystal RG. 2006. Neutralized adenovirus-immune complexes can mediate effective gene transfer via an Fc receptor-dependent infection pathway. J. Virol. 80: 10237–10247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lieber A, et al. 1997. The role of Kupffer cell activation and viral gene expression in early liver toxicity after infusion of recombinant adenovirus vectors. J. Virol. 71: 8798–8807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liniger M, Zuniga A, Naim HY. 2007. Use of viral vectors for the development of vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 6: 255–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu MA. 2010. Immunologic basis of vaccine vectors. Immunity 33: 504–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lux A, Nimmerjahn F. 2012. Impact of differential glycosylation on IgG activity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 780: 113–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Manickan E, et al. 2006. Rapid Kupffer cell death after intravenous injection of adenovirus vectors. Mol. Ther. 13: 108–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muruve DA, et al. 2008. The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature 452: 103–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. O'Brien KL, et al. 2009. Adenovirus-specific immunity after immunization with an Ad5 HIV-1 vaccine candidate in humans. Nat. Med. 15: 873–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Olivier V, Duval JL, Hindié M, Pouletaut P, Nagel MD. 2003. Comparative particle-induced cytotoxicity toward macrophages and fibroblasts. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 19: 145–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Overwijk WW, Surman DR, Tsung K, Restifo NP. 1997. Identification of a Kb-restricted CTL epitope of beta-galactosidase: potential use in development of immunization protocols for “self” antigens. Methods 12: 117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parker AL, et al. 2009. Effect of neutralizing sera on factor x-mediated adenovirus serotype 5 gene transfer. J. Virol. 83: 479–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Perreau M, Pantaleo G, Kremer EJ. 2008. Activation of a dendritic cell-T cell axis by Ad5 immune complexes creates an improved environment for replication of HIV in T cells. J. Exp. Med. 205: 2717–2725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pichla-Gollon SL, et al. 2009. Effect of preexisting immunity on an adenovirus vaccine vector: in vitro neutralization assays fail to predict inhibition by antiviral antibody in vivo. J. Virol. 83: 5567–5573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pilankatta R, Chawla T, Khanna N, Swaminathan S. 2010. The prevalence of antibodies to adenovirus serotype 5 in an adult Indian population and implications for adenovirus vector vaccines. J. Med. Virol. 82: 407–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pleass RJ. 2009. Fc-receptors and immunity to malaria: from models to vaccines. Parasite Immunol. 31: 529–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Quimby FW. 1999. The mouse, p 3–33 In Loeb WF, Quimby FW. (ed), The clinical chemistry of laboratory animals, second ed. Taylor and Francis, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raper SE, et al. 2003. Fatal systemic inflammatory response syndrome in a ornithine transcarbamylase deficient patient following adenoviral gene transfer. Mol. Genet. Metab. 80: 148–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27: 493–497 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sakurai F. 2008. Development and evaluation of a novel gene delivery vehicle composed of adenovirus serotype 35. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31: 1819–1825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sakurai F, Kawabata K, Mizuguchi H. 2007. Adenovirus vectors composed of subgroup B adenoviruses. Curr. Gene Ther. 7: 229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schroeder HW, Cavacini L. 2010. Structure and function of immunoglobulins. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125: S41–S52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Seiler MP, Cerullo V, Lee B. 2007. Immune response to helper dependent adenoviral mediated liver gene therapy: challenges and prospects. Curr. Gene Ther. 7: 297–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Seregin SS, Amalfitano A. 2009. Overcoming pre-existing adenovirus immunity by genetic engineering of adenovirus-based vectors. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 9: 1521–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shanbhag AS, Jacobs JJ, Black J, Galante JO, Glant TT. 1994. Macrophage/particle interactions: effect of size, composition and surface area. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 28: 81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shayakhmetov DM, Gaggar A, Ni S, Li ZY, Lieber A. 2005. Adenovirus binding to blood factors results in liver cell infection and hepatotoxicity. J. Virol. 79: 7478–7491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sumida SM, et al. 2005. Neutralizing antibodies to adenovirus serotype 5 vaccine vectors are directed primarily against the adenovirus hexon protein. J. Immunol. 174: 7179–7185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thacker EE, Timares L, Matthews QL. 2009. Strategies to overcome host immunity to adenovirus vectors in vaccine development. Expert Rev. Vaccines 8: 761–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thorner AR, et al. 2006. Age dependence of adenovirus-specific neutralizing antibody titers in individuals from sub-Saharan Africa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44: 3781–3783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tollefson AE, Kuppuswamy M, Shashkova EV, Doronin K, Wold WS. 2007. Preparation and titration of CsCl-banded adenovirus stocks. Methods Mol. Med. 130: 223–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Worgall S, et al. 2007. Protective immunity to Pseudomonas aeruginosa induced with a capsid-modified adenovirus expressing P. aeruginosa OprF. J. Virol. 81: 13801–13808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu Z, Tian J, Smith JS, Byrnes AP. 2008. Clearance of adenovirus by Kupffer cells is mediated by scavenger receptors, natural antibodies, and complement. J. Virol. 82: 11705–11713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yang TC, et al. 2007. T-cell immunity generated by recombinant adenovirus vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 6: 347–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yang Y, Wilson JM. 1995. Clearance of adenovirus-infected hepatocytes by MHC class I-restricted CD4+ CTLAs in vivo. J. Immunol. 155: 2564–2570 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang Y, Jooss K, Su Q, Ertl HC, Wilson JM. 1996. Immune responses to viral antigens versus transgene product in the elimination of recombinant adenovirus-infected adenovirus hepatocytes in vivo. Gene Ther. 3: 137–144 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zaiss AK, Machado HB, Herschman HR. 2009. The influence of innate and pre-existing immunity on adenovirus therapy. J. Cell. Biochem. 108: 778–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhu J, Huang X, Yang Y. 2007. Innate immune response to adenoviral vectors is mediated by both Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent pathways. J. Virol. 81: 3170–3180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]