Abstract

Though Pleistocene refugia are frequently cited as drivers of species diversification, comparisons of molecular divergence among sister species typically indicate a continuum of divergence times from the Late Miocene, rather than a clear pulse of speciation events at the Last Glacial Maximum. Community-scale inference methods that explicitly test for multiple vicariance events, and account for differences in ancestral effective population size and gene flow, are well suited for detecting heterogeneity of species' responses to past climate fluctuations. We apply this approach to multi-locus sequence data from five co-distributed frog species endemic to the Wet Tropics rainforests of northeast Australia. Our results demonstrate at least two episodes of vicariance owing to climate-driven forest contractions: one in the Early Pleistocene and the other considerably older. Understanding how repeated cycles of rainforest contraction and expansion differentially affected lineage divergence among co-distributed species provides a framework for identifying evolutionary processes that underlie population divergence and speciation.

Keywords: community phylogeography, lineage divergence, Litoria, Australia Wet Tropics

1. Introduction

Climatic oscillations during the Late Quaternary greatly affected the global distribution of biomes and sea levels, with concomitant effects on the distributions and diversification of species [1]. These climatic oscillations, driven by Milankovitch orbital cycles, repeatedly altered the distributions of biomes and species from the Late Miocene continuing throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene [2,3]. In spite of the cyclical nature of these fluctuations, many phylogeographic studies focus on the effects of the Late Pleistocene, and especially the rapid and pronounced cycles of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), from which the richest palaeo-ecological records are available. Though Pleistocene refugia are frequently depicted as drivers of species diversification, comparisons of molecular divergence among sister species indicate a continuum of divergence times from the Late Miocene to Recent, rather than a clear pulse of speciation events at the LGM [4–8]. Comparative studies of birds suggest that reproductively isolated sister taxa with overlapping distributions typically split during the Pliocene or Early Pleistocene and experienced recurrent cyclic changes whereas lineages that diverged during the Late Pleistocene more often show incomplete isolation or are non-overlapping geographically [4,9–12]. Conversely, genetic or phenotypic divergence established during glacial periods may be reversed by intermittent (e.g. interglacial) connections and subsequent widespread introgression between previously isolated populations [3,13].

Phylogeography across multiple species with overlapping ranges provides a powerful approach for evaluating models of single versus multiple climate-driven vicariance events across a shared landscape [14,15]. Variation in molecular (mitochondrial and allozyme) divergence among species with a geographically congruent phylogeographic break is a well-documented pattern [15]. A more rigorous approach is needed, however, to disentangle the effects of ancestral effective population size and potential gene flow during periods of high connectivity (e.g. [16]). Community-scale inference methods that account for these interacting processes and explicitly test for heterogeneity of divergence times are well suited for detecting variation in species' responses to climate fluctuation [17,18]. Application of this approach to comparative mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) phylogeographic data has revealed disparate divergence times (multiple vicariance events) for marine taxa across the isthmus of Panama [17] and for terrestrial taxa across the central Baja peninsula [19]. mtDNA, like any single gene, is subject to stochastic processes and artefacts owing to selection [20]; thus combining mtDNA and multiple nuclear DNA (nuDNA) loci should provide more reliable inference of community-scale response to habitat fluctuation. Here, we extend the community phylogeographic approach from mtDNA to a comparative multi-locus analysis to test for single versus multiple vicariance events in stream-breeding frogs from the rainforests of northeastern Australia—the ‘Australian Wet Tropics’.

The Australian Wet Tropics (AWT) rainforests have emerged as a model system for understanding effects of climate-driven habitat fluctuation on distributions and genetic diversity of widespread and montane taxa [21–24]. Initial comparative phylogeography of frogs and lizards revealed several-fold differences in mtDNA divergence across a common biogeographic break—the Black Mountain Corridor (BMC)—indicating divergence times that ranged from the LGM to the Pliocene or earlier ([22], reviewed in [25]). Multi-locus analyses of reptiles indicate deep (Early Pleistocene–Pliocene) divergences between phylogeographic lineages [26,27] and more recent range expansions. These results are spatially consistent with models of potential species' ranges under inferred LGM palaeoclimates; yet the estimated divergence times clearly predate the most recent cycle of climate oscillations. Thus, we hypothesize that preceding climatic cycles also sundered species ranges into divergent lineages that have not been obscured by subsequent gene flow. Alternatively, and for species tolerant of edge or open forest habitats in particular, ancient divergences among refugial areas may be obscured by episodic introgression during rainforest expansion phases, which highlights the importance of implementing divergence models that include the potential for migration [28].

Using multi-locus sequence data (mtDNA and 7–10 nuDNA loci) from five species of co-distributed frogs, we test for the presence of single versus multiple vicariance events across the BMC. To the extent that the degree of rainforest restriction and reliance on streams affect species' responses to climatic fluctuation, we expect divergence times and migration rates to vary between species. Specifically, we expect to recover strongest signatures of isolation in species highly dependent on streams within rainforest habitats (e.g. Litoria serrata, Litoria rheocola and Litoria dayi), intermediate divergence in species restricted to specialized habitats (Litoria nannotis, a torrent specialist) but which can occur in dry forest as well as rainforest and minimal divergence with consistent migration in species restricted to neither rainforest nor specific stream habitats (e.g. Litoria jungguy) [29–31].

2. Methods

(a). Sampling details

We sampled across the AWT rainforest system, with equal representation of populations on both sides of the BMC suture zone. The exact location of the phylogeographic break varies slightly for each species; in particular, populations in the Malbon Thompson range and the Lamb Uplands are ‘northern’ in some species and ‘southern’ in others based on previous mitochondrial studies [25]. We stratified sampling across the geographical ranges of the species and known mtDNA lineages [22]. Litoria jungguy comprises the northern distribution of the L. lesueuri species complex [32], and multi-locus analyses indicate that all populations in the central–northern AWT are pure L. jungguy, whether they occur in open or closed forest habitats (J.B.M., S. Donnellan, C.M. 2011, unpublished data). The mitochondrial sampling ranged from 42 to 134 samples per species and the nuclear sampling ranged from 15 to 36 samples per species (electronic supplementary material, table S1).

(b). Genetic data collection

We extracted total genomic DNA from toe clips preserved in 95 per cent ethanol [33]. We amplified and sequenced one mitochondrial fragment (COI or ND4) in each species as well as 7–10 nuclear loci. To amplify COI (L. nannotis, L. rheocola, L. serrata, L. dayi), we used published primers (Cox/Coy [22]). Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) included 20 ng of total DNA in a final volume of 10 µl containing: 1× buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.6 µM of each primer, 0.4 µM dNTP mix and 0.04 units of Taq polymerase. Amplification was carried out as follows: initial denaturation for 3 min at 94°C, followed by 10 cycles (30 s denaturation at 94°C, 30 s annealing at 48°C, 60 s extension at 72°C), 25 cycles (30 s denaturation at 94°C, 30 s annealing at 50°C, 60 s extension at 72°C) and a final extension for 7 min at 72°C. For ND4 (L. jungguy), we used published primers (ND4 [34] and Limno2 [35]). PCRs included 20 ng of total DNA in a final volume of 10 µl containing: 1× buffer, 0.6 µM of each primer, 0.8 µM dNTP mix and 0.025 units of Taq polymerase. Amplification was carried out as follows: initial denaturation for 3 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles (45 s denaturation at 94°C, 45 s annealing at 55°C, 60 s extension at 72°C) and a final extension for 7 min at 72°C.

For nuclear genes, we used one published locus (β-crystallin [36]) and developed further nuclear loci by sequencing clones from a cDNA library for L. serrata, which were blasted against the Gallus and Xenopus genomes to establish the locations of exon and, by inference, intron regions. Primers, designed using Primer3 v. 0.4.0 [37], were anchored in conserved regions of exons flanking the intron sequence. Details for loci developed in this study are in electronic supplementary material, table S2. PCRs included 20 ng of total DNA in a final volume of 12.5 µl containing: 1× buffer, 1 µM betaine, 0.75 µM of each primer, 0.08 µM dNTP mix and 0.04 units of Taq polymerase. Amplification was carried out with initial denaturation for 3 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles (30 s denaturation at 95°C, 30 s annealing at 57–59°C (electronic supplementary material, table S2) and 45 s extension at 72°C) and a final extension for 7 min at 72°C. Depending on the species, we amplified approximately 2300 total base pairs across seven loci to 4400 total base pairs across 10 loci. PCR products were visualized on an agarose gel, purified using ExoSAP-IT (USB) and sequenced using BigDye v. 3.1 (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 3730 automated DNA sequencer. DNA sequences were edited using Sequencher v. 4.7 (Gene Codes Corporation) and are accessioned in GenBank (JN130400–JN131474). Sequences less than 200 base pairs in length are deposited in the Dryad Repository (doi:10.5061/dryad.1cf5d).

(c). Mitochondrial data analysis

Sequences were aligned using ClustalX v. 2.0.10 [38]. We implemented MrModel Test v. 2.3 [39] to establish which substitution models best fit each dataset (HKY for L. dayi; HKY + G for L. jungguy, L. rheocola and L. serrata; and GTR + G for L. nannotis). Bayesian phylogenetic analyses were conducted using MrBayes v. 3.1.2 [40] with datasets partitioned by codon position. We allowed six incrementally heated Markov chains to proceed for 20 million generations, sampling every 1000 generations. Bayesian posterior probability values were estimated from the sampled trees remaining after 2000 burn-in samples were discarded and convergence was evaluated using the standard deviation of split frequencies. We used Arlequin v. 3.1 [41] to calculate nucleotide diversity (θs, θπ) and sequence divergence (Dxy and Da using the Tamura–Nei model) for the northern and southern lineages.

(d). Nuclear data analysis

Sequences were aligned using ClustalX v. 2.0.10 [38]. To resolve haplotypes from heterozygous individuals, we used Phase v. 2.1 [42]. For individuals with heterozygous indels, we used CodonCode Aligner v. 2.0 (CodonCode Corporation) to resolve haplotypes. For the northern and southern lineages, we calculated nucleotide diversity (θs, θπ) and sequence divergence among populations (Dxy and Da using the Tamura–Nei model). All calculations were conducted in Arlequin v. 3.1 [41]. We used a linear model (implemented in R v. 2.9.2) to test for an association between mitochondrial and average nuclear values of sequence divergence (Da) and nucleotide diversity (θπ).

To visually represent overall divergence patterns, we used a multi-locus, individual-based network approach. We used Paup v. 4.0 [43] to create genetic distance matrices between phased haplotypes at each locus using the HKY85 [44] model. Using Pofad v. 1.03 [45], we combined individual locus matrices into one, multi-locus distance matrix (equally weighted across loci). Finally, we constructed a genetic network of the multi-locus distance matrix in SplitsTree v. 4.6 [46] using the NeighborNet algorithm [47].

(e). Test of simultaneous vicariance

To explicitly test for simultaneous vicariance in the five taxa, we used MTML-msBayes, a hierarchical approximate Bayesian computation (ABC) method that allows for across-species demographic variation, inter-gene variability in coalescent times and DNA mutation rate heterogeneity [48,49]. The analysis was conducted in three stages. We first compared models of migration versus isolation post-divergence for each species, then we tested for temporal congruence in divergence and finally, we estimated the timing of divergence events. For comparison, all three stages of analysis were conducted using the mtDNA-only dataset, as well as the combined mtDNA and nuDNA dataset. To avoid confounding the analysis, we removed L. jungguy samples from localities with potential hybridization.

To compare the relative likelihood of a model with complete isolation between lineages north and south of the BMC (species-pairs) versus a model with low levels of post-isolation migration, we used ABC model choice for each of the five species. Under the post-isolation migration model, migration ranged from 0 to 1.0 migrants per generation across the BMC after the time of isolation. Simulated data using parameter values randomly drawn from both isolation and migration models with equal probability (3 000 000 simulations each) were used to approximate the posterior probability of these two models by using the 500–1000 shortest Euclidian distances of the summary statistic vectors (see below) between the observed data and the corresponding 500–1000 simulated datasets out of a total 6 000 000 simulated datasets. This was followed by a logistical regression transformation between the two model indicator variables and corresponding simulated summary statistic vectors to improve the accuracy of the posterior model choice procedure [50]. A Bayes factor was used to compare support for either the isolation or migration model [51].

The ABC model choice procedure used a summary statistic vector consisting of five quantities that in combination are shown to discriminate between isolation and migration models given multi-locus data and this hierarchical ABC technique [49]. These are: (i) π, the average number of pairwise differences among all sequences within each species pair; (ii) qW, the number of segregating sites within each species pair normalized for sample size [52]; (iii) s.d. (π − qW), the standard deviation in the difference between these two quantities; (iv) πnet, net average pairwise differences between two descendent species samples [53]; and (v) Wakeley's ΨW, a derivation of the interpopulation correlation coefficient of the number of pairwise differences between species pairs. This latter summary statistic was originally developed to be useful for distinguishing migration from isolation models [54,55].

The second stage of the analysis estimated the amount of temporal congruence for vicariance across the BMC in all five species while incorporating for each species the divergence model with the greatest support (complete isolation or low levels of migration). Under the most probable model, hierarchical ABC was used to estimate Var(τ)/E(τ), the dispersion index of divergence times (τ) which takes a value of 0 under simultaneous vicariance. All possible multi-taxa models of divergence were modelled by exploring the full hyper-prior range of the hyper-parameter Ψ, the number of different divergence times across a total of Y species pairs under the most likely model, whereby Ψ is drawn from a discrete uniform hyper-prior, in this case ranging from 1 (simultaneous vicariance) to 5 (complete incongruent vicariance). To quantify the posterior strength in comparing simultaneous with non-simultaneous vicariance, a Bayes factor B(Ψ = 1,Ψ > 1) was calculated, such that values greater than 10 suggested strong support of simultaneous vicariance [51].

The third stage of analysis involved estimating the common divergence times across taxa for which there is support for simultaneous vicariance. The divergence time (τi) of each of the Y taxon-pairs was scaled for each taxon-pair relative to its effective population size (Ni), i.e. ti = τi 4Nig, where g is the generation time in years. To estimate a common divergence time across species, given that each species has a unique value of Ni, each τi was rescaled using the relationship τ = τiθib, where b = θAVE/θi, and θAVE is the mean of the prior for θ. For example, if a population pair happens to have a small Ni and a large τi (in units of 4Nig), its globally expressed divergence time τ will be directly comparable to a population pair with an equal divergence in absolute time but with differing Ni (and hence differing τi). Conversion of each divergence event τ into years is then t = τ 4NAVE g, where 4NAVE = θAVE/μ and μ is the average per gene per generation mutation rate. Generally, loci are assumed to be unlinked and have rate variability with rate differences that are scaled from the mean of a gamma distribution. We used a mean substitution rate of 1 per cent Myr–1 for mitochondrial genes [56] and a mean substitution rate of 0.2 per cent Myr–1 for nuclear genes, the latter based on estimates of mutation scalars inferred from preliminary IMa analyses [57]. Gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity across genes and uncertainty in the shape parameter α of this gamma distribution were incorporated by randomly drawing α from a uniform hyper-prior distribution as described in Huang et al. [49].

In both the second and third stages of analysis, we used the 500–1000 shortest Euclidian distances between the observed summary statistic vectors and those calculated from the corresponding 500–1000 simulated datasets out of a total of 3 000 000–15 000 000 simulated datasets using hyper-parameter values randomly drawn from the hyper-prior [49]. To improve ABC estimation of the dispersion index of divergence times and the divergence times themselves, we use weighted local linear regression on the 500–1000 accepted summary statistic vectors and their associated hyper-parameter values [58]. As in the first stage comparing isolation and migration models, when calculating B(Ψ = 1,Ψ > 1) to compare hyper-posterior probabilities between simultaneous and non-simultaneous vicariance, we use a polychotomous regression adjustment on the 500–1000 accepted summary statistic vectors and their associated hyper-parameter values [50].

3. Results

(a). Mitochondrial and nuclear phylogeography

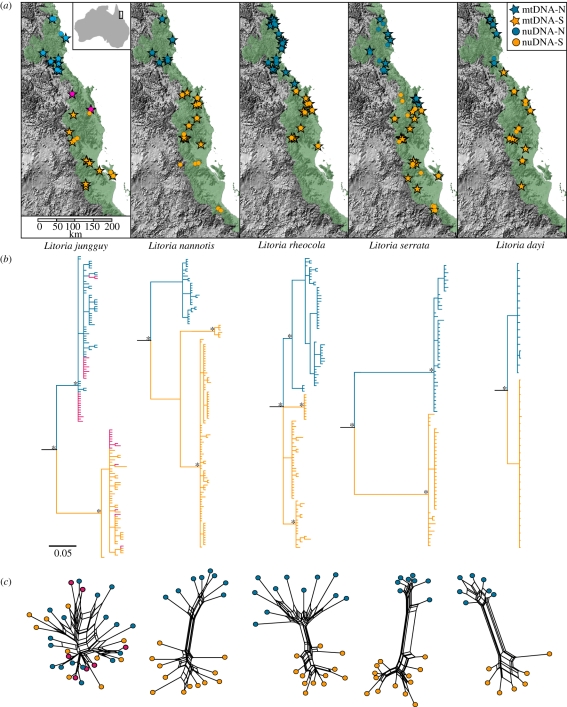

The mitochondrial phylogenies of all five species recovered varying levels of net sequence divergence (dA) between lineages north and south of the BMC region, ranging from 1.6 per cent in L. rheocola, to 14.4 per cent in L. serrata, with intermediate values in L. jungguy (3.7%), L. dayi (6.2%) and L. nannotis (6.5%; figure 1 and electronic supplementary material, table S3). Consistent with previous studies [22], L. nannotis populations south of the BMC formed two highly divergent (dA = 6.7%) parapatric lineages: one in the central AWT and the other in the south.

Figure 1.

(a) Localities for mtDNA and nuDNA sampling for each species, relative to the distribution of the AWT rainforest. (b) mtDNA trees for each species. Posterior probabilities greater than 95% are indicated by asterisks. (c) Multi-locus nuDNA networks generated using Pofad and SplitsTree. In all cases, samples are coloured according to northern (blue circles, nuDNA; blue stars, mtDNA) and southern (orange circles, nuDNA; orange stars, mtDNA) mitochondrial lineages. The populations of L. jungguy with sympatric mtDNA lineages are shown in pink. Pairwise distances for nuclear loci are given in electronic supplementary material, table S3.

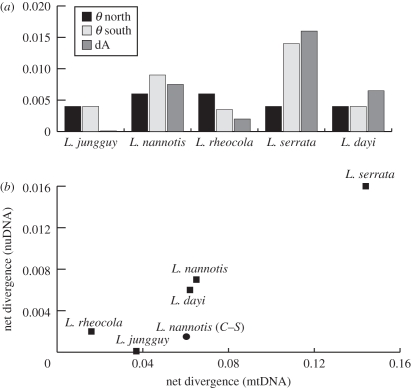

The multi-locus distance networks were largely congruent with the mitochondrial phylogeography in terms of locations of genetic breaks and the relative magnitude of divergence (figure 1). There were two notable exceptions. First, though most northern and southern populations of L. jungguy were reciprocally monophyletic in the mitochondrial phylogeography, there was substantial geographical overlap of these mtDNA lineages in the central AWT and the nuclear loci indicated very little, if any, differentiation across the BMC (dA = 0.001, p > 0.05). Second, there was no corresponding nuclear gene divergence (dA = 0.001, p > 0.05) between the distinct southern and central mitochondrial lineages of L. nannotis. Otherwise, estimates of nuclear gene divergence (dA) between lineages distributed either side of the BMC suture zone were significant and were correlated with mitochondrial estimates with an approximately 10-fold difference in per cent divergence (slope = 0.12, p < 0.01; figure 2 and electronic supplementary material, table S3). In contrast, estimates of nuclear gene diversity within lineages (θπ) were highly variable and were not correlated to corresponding estimates for mtDNA (slope = −0.02, p > 0.05; electronic supplementary material, table S3).

Figure 2.

(a) Indices of genetic diversity within (θ), and net divergence between (dA, dark grey bars), northern (black bars) and southern lineages (light grey bars). (b) Mitochondrial and nuclear estimates of net divergence across the BMC are highly correlated (slope = 0.12, p < 0.01). Mitochondrial and nuclear estimates of divergence between the central and southern lineages of L. nannotis (circle) deviate from this pattern.

(b). Test of simultaneous vicariance

Given the mtDNA data only, Bayes factors strongly supported isolation over migration for all five species (Bayes factor = 275.50). In the multi-locus analyses, however, Bayes factors strongly supported isolation in three of the five taxon-pairs (L. serrata, L. nannotis and L. dayi, Bayes factors from 11.03 to 31.61) but could not resolve an isolation model from a low-migration model in the other two taxa (L. jungguy and L. rheocola, Bayes factors = 0.49 and 0.48). Therefore, we performed subsequent analysis separately for these two groupings of taxon-pairs, considering L. jungguy and L. rheocola under both the isolation and the migration models and the pure isolation model only for L. serrata, L. nannotis and L. dayi.

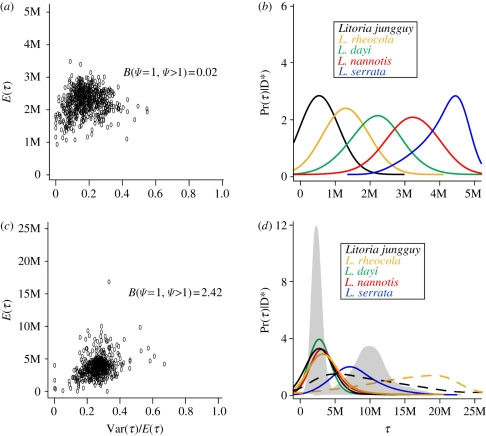

The mtDNA-only and combined datasets were indicative of multiple vicariance events, though support for multiple vicariance was slightly decreased in the analyses that split taxa to allow for differing histories of post-divergence migration. When we assumed no migration post-isolation in both the mtDNA-only and the combined datasets, there was little support for simultaneous vicariance events across all five taxon-pairs (mtDNA only B(Ψ = 1,Ψ > 1) = 0.02 and combined data B(Ψ = 1,Ψ > 1) = 2.42, figure 3)). When we analysed the two groupings of taxon-pairs separately with the combined dataset, we likewise found little support for simultaneous vicariance events across the BMC in either the three taxa that diverged under the isolation model (B(Ψ = 1,Ψ > 1) = 3.06) or the two taxa that diverged under the post-divergence migration model (B(Ψ = 1,Ψ > 1) = 1.07).

Figure 3.

(a,b) Results from mitochondrial-only and (c,d) multi-locus msBayes analyses. (a,c) The approximate joint posterior estimates of Var(τ)/E(τ), the dispersion index of τ and E(τ), the mean of τ. (b,d) Posterior probability densities for τ, the divergence time for each of the five lineage pairs. The solid lines represent estimates under the isolation model and the dashed lines in (d) represent estimates for L. rheocola and L. jungguy under the low-migration model. The joint divergence time estimates for the four taxa that diverged in the Mid-Pleistocene and for L. serrata, which diverged in the Pliocene, are shown in grey. Note that the single and multi-locus msBayes analyses have different timescales.

The mitochondrial-only analyses indicated a spread of divergence times across species ranging from approximately 0.5 Myr in L. jungguy to 4.5 Myr in L. serrata (figure 3b). Our multi-locus analyses demonstrated that isolation and divergence across the BMC into southern and northern lineages, with the exception of L. serrata, was more temporally congruent (Bayes factor for 2 versus greater than 2 divergence times = 3.56) and commenced in the Early Pleistocene or Late Pliocene (figure 3d). When we allowed for some introgression across the BMC in L. jungguy and L. rheocola, however, we recovered additional periods of isolation and divergence and the temporal estimate for these periods was much less certain (dashed lines in figure 3d). To get the most accurate temporal estimate of community-scale vicariance in the four taxa that probably split in the Early Pleistocene (no migration model, figure 3d), we ran the hierarchical ABC model to test for simultaneous vicariance and the corresponding divergence time estimate [17]. In this case, the timing of simultaneous isolation of northern versus southern lineages of L. jungguy, L. rheocola, L. dayi and L. nannotis was in the Early Pleistocene (Bayes factor = 4668.00) approximately 1.5 Myr before present (95% credibility interval: 30 000–3.70 Myr). The split between northern and southern lineages of L. serrata was older, most probably in the Early Pliocene or Late Miocene approximately 5.8 Mya (figure 3d; 95% credibility interval: 3.70–17.08 Myr).

4. Discussion

Using multi-locus sequence data from five co-distributed frog species, we demonstrate temporal heterogeneity in response to a common history of climate-driven forest dynamics. Substantial variation in the degree of genetic differentiation of all five species across the BMC is apparent from the mitochondrial phylogeography. For instance, in L. serrata, the genetic break across the BMC is very deep with minimal fine-scale genetic structure within either the northern or southern lineages. At the other extreme, L. rheocola exhibits shallow genetic divergence across the BMC and more structured genetic diversity within each of the northern and southern lineages (see also [22]). Community-scale inference methods, based on the mtDNA-only and on the multi-locus dataset, indicate substantial variation in the timing and degree of historical isolation, with consistent support for multiple vicariance events.

The timing and degree of isolation for each of the five species is only partly associated with ecological specialization and dependence on rainforest habitats. Litoria serrata, one of the species with the greatest degree of ecological specialization, exhibits signatures of long-term isolation and substantial divergence dating to the Pliocene. The other two species highly dependent on the rainforest habitat (L. rheocola and L. dayi) as well as the two species less reliant on the rainforest habitat (L. nannotis and L. jungguy) exhibit signatures of divergence consistent with more recent isolation, or in the case of L. jungguy and L. rheocola, ancient divergence with varying levels of subsequent gene flow.

In general, the nuclear loci are consistent with the mitochondrial phylogeography, and the nuclear and mitochondrial estimates of sequence divergence across the BMC are highly correlated with an approximately 10-fold difference. However, inconsistencies between mtDNA and nuDNA in L. nannotis and in L. jungguy amply illustrate the importance of multi-locus studies. For example, the populations of L. nannotis south of the BMC form two distinct mitochondrial lineages, a pattern documented in previous molecular studies [22], but this division is not supported by nuclear loci. Though this discrepancy may result from stochastic processes [59] or geographically varying selection on mtDNA [60], it might also reflect Early Holocene expansion of the central lineage into relictual southern populations, with distinct southern mitochondrial alleles becoming fixed at the wavefront (allele surfing [61]). Like L. nannotis, several reptiles endemic to wet tropics, such as Carlia rubrigularis [26], Lampropholis coggeri [27] and Saproscincus basiliscus [62], also exhibit distinct mtDNA lineages in the southern AWT, and for L. coggeri, this is supported by multi-locus data. All three species along with L. nannotis are tolerant of edge habitats [31], such that they could have persisted in marginal habitats during glacial periods.

The inconsistency between markers in L. jungguy is considerable in that the mitochondrial divergence observed between northern and southern populations is not recovered across multiple nuclear loci. In this instance, minimal structure across multiple nuclear loci indicates either broad-scale introgression across a broad contact zone in the central AWT, or perhaps that populations of L. jungguy remained connected across the BMC during the extended periods of rainforest replacement by drier habitats. Litoria jungguy, in contrast to most wet tropics species, tolerate dry forest habitats and are broadly distributed throughout dry sclerophyll forests in northeast Australia [32]; thus, it is conceivable that rainforest contraction did not limit migration across the range of this species.

Though mtDNA alone are often sufficient to detect major historical lineages [63], and here mtDNA lineages distributed either side of the BMC barrier are typically congruent with nuDNA evidence, multi-locus analyses are critical to obtain reliable estimates of historical demographic parameters that provide insight into underlying processes [64]. Our analysis of community vicariance based on a single mitochondrial locus is suggestive of multiple vicariance events, but lacks the statistical power to estimate the number and timing of divergence events. In contrast, the multi-locus analysis clearly rejects a single vicariance event in favour of two discrete episodes of vicariance, and while estimates of divergence time remain approximate, they are generally consistent with repeated effects of Pliocene and Pleistocene climate cycling across this geologically stable landscape. When we allow, in appropriate cases, for post-divergence migration in the multi-locus analysis, we still reject simultaneous vicariance across the five species, but the number and timing of divergence events are more ambiguous. This ambiguity reflects the increase in complexity of models and probably requires a substantial increase in the number of independent loci to resolve. The demographic models for both L. rheocola and L. jungguy were consistent with low levels of migration post-isolation. Though this implies that episodes of rainforest contraction did not limit migration across the BMC as strongly in these species, ephemeral divergence or multiple cycles of isolation and subsequent introgression can produce a similar pattern of apparent genetic and phenotypic stasis [13].

This study clearly demonstrates the advantages of comparative phylogeography, across both taxa and multiple loci, for disentangling how repeated vicariance events shape genetic diversity in a biogeographic system. Studies of community vicariance inform how species differ in their responses to a shared geographical and climatic history, and also shape expectations for further studies of speciation and the evolution of reproductive isolation. For instance, lineages that diverged in response to earlier (e.g. Pliocene or Late Miocene) climatic fluctuations are expected to exhibit stronger post-zygotic isolation than those that formed in response to more recent (Mid–Late Pleistocene) climatic cycles [4,12]. Previous studies of the early-diverging lineages of L. serrata (formerly Litoria genimaculata) found strong post-zygotic isolation and also evidence for pre-zygotic isolation when there is potential for reinforcement [65]. Divergence in the other species examined in this study is more recent; thus, we predict that reproductive isolation between lineages will be weaker in these taxa. Understanding how repeated cycles of rainforest contraction and expansion shaped current genetic diversity provides a framework for identifying evolutionary processes that underlie population divergence and speciation.

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Hoskin, A. Anderson, A. C. Carnaval, M. Higgie and M. Tonione, for assistance with fieldwork, V. Alla and J. Vo for assistance in the laboratory, and S. Singhal and three anonymous reviewers for comments that improved the manuscript. msBayes analyses were performed on the City University of New York HPCF (High Performance Computing Facility). MrBayes analyses were performed at Cornell Computational Biology Service Unit, a facility partially funded by the Microsoft Corporation. Support for M.J.H. was provided by the National Science Foundation (DEB-0743648). This work was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation to C.M. (DEB0416250, 0817035).

References

- 1.Hewitt G. M. 2004. Genetic consequences of climatic oscillations in the Quaternary. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 359, 183–195 10.1098/rstb.2003.1388 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2003.1388) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett K. D. 1990. Milankovitch cycles and their effects on species in ecological and evolutionary time. Paleobiology 16, 11–21 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dynesius M., Jansson R. 2000. Evolutionary consequences of changes in species' geographical distributions driven by Milankovitch climate oscillations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 9115–9120 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9115 (doi:10.1073/pnas.97.16.9115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avise J. C., Walker D. 1998. Phylogeographic effects on avian populations and the speciation process. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265, 457–463 10.1098/rspb.1998.0317 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0317) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klicka J., Zink R. M. 1999. Pleistocene effects on North American songbird evolution. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 695–700 10.1098/rspb.1999.0691 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0691) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rull V. 2009. Microrefugia. J. Biogeogr. 36, 481–484 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.02023.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.02023.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson N. K., Cicero C. 2004. New mitochondrial DNA data affirm the importance of Pleistocene speciation in North American birds. Evolution 58, 1122–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weir J. T., Schluter D. 2004. Ice sheets promote speciation in boreal birds. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, 1881–1887 10.1098/rspb.2004.2803 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2803) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prigogine A. 1987. Disjunctions of montane forest birds in the Afrotropical region. Bonn. Zool. Beit. 38, 195–207 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haffer J. 2008. Hypotheses to explain the origin of species in Amazonia. Braz. J. Biol. 68, 917–947 10.1590/S1519-69842008000500003 (doi:10.1590/S1519-69842008000500003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voelker G., Outlaw R. K., Bowie R. C. 2010. Pliocene forest dynamics as a primary driver of African bird speciation. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 19, 111–121 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00500.x (doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00500.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weir J. T., Price T. D. 2011. Limits to speciation inferred from times to secondary sympatry and ages of hybridizing species along a latitudinal gradient. Am. Nat. 177, 462–469 10.1086/658910 (doi:10.1086/658910) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Futuyma D. J. 2010. Evolutionary constraint and ecological consequences. Evolution 64, 1865–1884 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.00960.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.00960.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bermingham E., Mortiz C. 1998. Comparative phylogeography: concepts and applications. Mol. Ecol. 7, 367–369 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00424.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00424.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avise J. A. 2000. Phylogeography: the history and formation of species. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dasmahapatra K. K., Lamas G., Simpson F., Mallet J. 2010. The anatomy of a ‘suture zone’ in Amazonian butterflies: a coalescent-based test for vicariant geographic divergence and speciation. Mol. Ecol. 19, 4283–4301 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04802.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04802.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickerson M. J., Stahl E., Lessios H. A. 2006. Test for simultaneous divergence using approximate Bayesian computation. Evolution 60, 2435–2453 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hickerson M. J., Meyer C. P. 2008. Testing comparative phylogeographic models of marine vicariance and dispersal using a hierarchical Bayesian approach. BMC Evol. Biol. 8, 322. 10.1186/1471-2148-8-322 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-322) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leaché A., Crews S. A., Hickerson M. J. 2007. Two waves of diversification in mammals and reptiles of Baja California revealed by hierarchical Bayesian analysis. Biol. Lett. 3, 646–650 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0368 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0368) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg N. A., Nordborg M. 2002. Genealogical trees, coalescent theory, and the analysis of genetic polymorphisms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 380–390 10.1038/nrg795 (doi:10.1038/nrg795) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams S. E., Pearson R. G. 1997. Historical rainforest contractions, localized extinctions and patterns of vertebrate endemism in the rainforests of Australia's wet tropics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 264, 709–716 10.1098/rspb.1997.0101 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider C. J., Cunningham M., Moritz C. 1998. Comparative phylogeography and the history of endemic vertebrates in the Wet Tropics rainforests of Australia. Mol. Ecol. 7, 487–498 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00334.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00334.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hugall A., Moritz C., Moussalli A., Stanisic J. 2002. Reconciling paleodistribution models and comparative phylogeography in the Wet Tropics rainforest land snail Gnarosophia bellendenkerensis (Brazier 1875). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6112–6117 10.1073/pnas.092538699 (doi:10.1073/pnas.092538699) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham C. H., Moritz C., Williams S. E. 2006. Habitat history improves prediction of biodiversity in rainforest fauna. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 632–636 10.1073/pnas.0505754103 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0505754103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moritz C., Hoskin C. J., MacKenzie J. B., Phillips B. L., Tonione M., Silva N., VanDerWal J., Williams S. E., Graham C. H. 2009. Identification and dynamics of a cryptic suture zone in tropical rainforest. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 1235–1244 10.1098/rspb.2008.1622 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1622) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dolman G., Moritz C. 2006. A multilocus perspective on refugial isolation and divergence in rainforest skinks (Carlia). Evolution 60, 573–582 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell R. C., Parra J. L., Tonione M., Hoskin C. J., MacKenzie J. B., Williams S. E., Moritz C. 2010. Patterns of persistence and isolation indicate resilience to climate change in montane rainforest lizards. Mol. Ecol. 19, 2531–2544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen R., Wakeley J. 2001. Distinguishing migration from isolation: a Markov chain Monte Carlo approach. Genetics 158, 885–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams S. E., Hero J. M. 1998. Rainforest frogs of the Australian Wet Tropics: guild classification and the ecological similarity of declining species. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265, 597–602 10.1098/rspb.1998.0336 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0336) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowley J. L., Alford R. A. 2007. Movement patterns and habitat use of rainforest stream frogs in northern Queensland, Australia: implications for extinction vulnerability. Wildl. Res. 34, 371–378 10.1071/WR07014 (doi:10.1071/WR07014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams S. E., et al. 2010. Distributions, life history specialisation and phylogeny of the rainforest vertebrates in the Australian Wet Tropics. Ecology 91, 2493. 10.1890/09-1069.1 (doi:10.1890/09-1069.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donnellan S. C., Mahony M. J. 2004. Allozyme, chromosomal and morphological variability in the Litoria lesueuri species group (Anura: Hylidae), including a description of a new species. Aust. J. Zool. 52, 1–28 10.1071/ZO02069 (doi:10.1071/ZO02069) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aljanabi S. M., Martinez I. 1997. Universal and rapid salt-extraction of high quality genomic DNA for PCR-based techniques. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4692–4693 10.1093/nar/25.22.4692 (doi:10.1093/nar/25.22.4692) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arevalo E., Davis S. K., Sites J. W. 1994. Sequence divergence and phylogenetic relationships among eight chromosome races of the Sceloporus grammicus complex (Phrynosomatidae) in Central Mexico. Syst. Biol. 43, 387–418 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schäuble C. S., Moritz C., Slade R. W. 2000. A molecular phylogeny for the frog genus Limnodynastes (Anura: Myobatrachidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 16, 379–391 10.1006/mpev.2000.0803 (doi:10.1006/mpev.2000.0803) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dolman G., Phillips B. 2004. Single copy nuclear DNA markers characterized for comparative phylogeography in Australian wet tropics rainforest skinks. Mol. Ecol. Not. 4, 185–187 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2004.00609.x (doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2004.00609.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rozen S., Skaletsky H. J. 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. In Bioinformatics methods and protocols: methods in molecular biology (eds Krawetz S., Misener S.), pp. 365–386 Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larkin M. A., et al. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nylander J. A. MrModeltest v. 2.0 program distributed by the author. Uppsala University, Sweden: Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huelsenbeck J. P., Ronquist F. 2001. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17, 754–755 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Excoffier L., Laval G., Schneider S. 2005. Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinform. 1, 47–50 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stephens M., Smith N. J., Donnelly P. 2001. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 978–989 10.1086/319501 (doi:10.1086/319501) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swofford D. L. 2003. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), v. 4.0 Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hasegawa M., Kishino H., Yano T. 1985. Dating the human–ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 22, 160–174 10.1007/BF02101694 (doi:10.1007/BF02101694) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joly S., Bruneau A. 2006. Incorporating allelic variation for reconstructing the evolutionary history of organisms from multiple genes: an example from Rosa in North America. Syst. Biol. 55, 623–636 10.1080/10635150600863109 (doi:10.1080/10635150600863109) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huson D. H., Bryant D. 2006. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 254–267 10.1093/molbev/msj030 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msj030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bryant D., Moulton V. 2004. Neighbor-net: an agglomerative method for the construction of phylogenetic networks. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 255–265 10.1093/molbev/msh018 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msh018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hickerson M. J., Stahl E., Takebayashi N. 2007. msBayes: A flexible pipeline for comparative phylogeographic inference using approximate Bayesian computation (ABC). BMC Bioinform. 8, 268. 10.1186/1471-2105-8-268 (doi:10.1186/1471-2105-8-268) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang W., Takebayashi N., Qi Y., Hickerson M. J. 2011. MTML-msBayes: approximate Bayesian comparative phylogeographic inference from multiple taxa and multiple loci with rate heterogeneity. BMC Bioinform. 12, 1. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-1 (doi:10.1186/1471-2105-12-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beaumont M. A. 2008. Selection and sticklebacks. Mol. Ecol. 17, 3425–3427 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03786.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03786.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kass R. E., Raftery A. 1995. Bayesian factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 90, 773–795 10.2307/2291091 (doi:10.2307/2291091) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watterson G. A. 1975. On the number of segregating sites in genetic models without recombination. Theor. Popul. Biol. 7, 256–276 10.1016/0040-5809(75)90020-9 (doi:10.1016/0040-5809(75)90020-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nei M., Li W. 1979. Mathematical model for studying variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 76, 5269–5273 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269 (doi:10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wakeley J. 1996. The variance of pairwise nucleotide differences in two populations with migration. Theor. Popul. Biol. 49, 39–57 10.1006/tpbi.1996.0002 (doi:10.1006/tpbi.1996.0002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wakeley J. 1996. Distinguishing migration from isolation using the variance of pairwise differences. Theor. Popul. Biol. 49, 369–386 10.1006/tpbi.1996.0018 (doi:10.1006/tpbi.1996.0018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roelants K., Gower D., Wilkinson M., Loader S., Biju S. D., Guillaume K., Moriau L., Bossuyt F. 2007. Global patterns of diversification in the history of modern amphibians. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 887–892 10.1073/pnas.0608378104 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0608378104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hey J., Nielsen R. 2007. Integration within the Felsenstein equation for improved Markov chain Monte Carlo methods in population genetics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 2785–2790 10.1073/pnas.0611164104 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0611164104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beaumont M. A., Zhang W., Balding D. J. 2002. Approximate Bayesian computation in population genetics. Genetics 162, 2025–2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Irwin D. E. 2002. Phylogeographic breaks without geographic barriers to gene flow. Evolution 56, 2383–2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ballard J. W. O., Whitlock M. C. 2004. The incomplete natural history of mitochondria. Mol. Ecol. 13, 729–744 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.02063.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.02063.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Excoffier L., Ray N. 2009. Surfing during population expansions promotes genetic revolutions and structuration. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 347–351 10.1016/j.tree.2008.04.004 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.04.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moussalli A., Moritz C., Williams S. E., Carnaval A. C. 2009. Variable responses of skinks to a common history of rainforest fluctuation: concordance between phylogeography and palaeo-distribution models. Mol. Ecol. 18, 483–499 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.04035.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.04035.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zink R. M., Barrowclough G. F. 2008. Mitochondrial DNA under siege in avian phylogeography. Mol. Ecol. 17, 2107–2121 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03737.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03737.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brito P. H., Edwards S. V. 2008. Multilocus phylogeography and phylogenetics using sequence-based markers. Genetica 135, 439–455 10.1007/s10709-008-9293-3 (doi:10.1007/s10709-008-9293-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoskin C. J., Higgie M., McDonald K. R., Moritz C. 2005. Reinforcement drives rapid allopatric speciation. Nature 437, 1353–1356 10.1038/nature04004 (doi:10.1038/nature04004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]