Abstract

Developing efficient cellular delivery vectors is crucial for designing novel therapeutic agents to enhance their plasma membrane permeability and metabolic stability in cells. Previously, we engineered cell penetrating peptide vectors named as “lipo-oligoarginine peptides” (LOAPs) by conjugating a proper combination of fatty acid and oligoarginine that translocated into cell easily without adverse effect on cell viability. In the present study, we report a systemic evaluation of cellular uptake and metabolic stability of LOAPs in Jurkat cells by introducing different combination of D-Arg residues in the peptide backbone. The cellular uptake and intracellular fate, cell viability, and metabolic stability and proteolytic degradation patterns of various LOAPs consisted of different combination of L- and D-Arg sequences were confirmed by flow cytometry, cytotoxicity assay, and analytical RP-HPLC with MALDI-TOF mass. All investigated LOAPs penetrated the cell efficiently with low cellular toxicity. The LOAPs having D-Arg residues at their N-termini seemed to have better metabolic stability than the LOAPs having C-terminal D-Arg residues. The metabolic degradation patterns were similar among all investigated LOAPs. The major hydrolytic site was between lauroyl group and β-Ala residue. Without the lipid chain, the oligoarginine peptide was pumped out of cells easily. The results presented in this study suggest that structurally modified LOAPs could be used as a novel CPP design toward improved therapeutic application.

Keywords: Cell penetrating peptide, Cellular uptake, Drug delivery system, Metabolic stability, Oligoarginine

1. Introduction

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) have been introduced as fascinating delivery vectors to transport various cargo molecules, such as proteins, nanoparticles, molecular imaging reporters, and generally hydrophilic molecules, into intracellular compartments based on their high cellular uptake efficiency.1–3 Cationic residues in CPPs, particularly guanidine moiety in Arg-rich peptides, have been known to play a crucial role for the membrane translocation capability.4,5 Recently we reported that a fine tuned lipo-oligoarginine peptides (LOAPs) consisted of optimized hydrophobic fatty acids and hydrophilic oligoarginines could enhance cellular uptake, and accumulation.6 The study suggests that the membrane translocation pathway of LOAPs was an energy dependent endocytosis, while a small fraction of LOAP was able to enter cells through an energy independent manner.

A major obstacle of using CPPs as delivery vectors is their low metabolic stability by enzymatic proteolysis because proteases are everywhere, including in cytoplasm, on the membrane, and even outside of cells. Although metabolic stability of CPPs is an important factor for their efficient cellular translocation and for sustained release of cargo molecules into targets, most CPPs are metabolically unstable that lead to rapid degradation before reaching the targets.7–11 The degradation process is usually started with a combined action of exoproteases, that cleave the C-terminal (carboxypeptidases) and/or N-terminal residues (aminopeptidases), as well as endoproteases, that cleave internal amide bonds at specific sites. In order to minimize proteolytical degradation, their peptide structures are often modified so that they are no longer labile to proteases. We recently introduced a more stable LOAPs backbone, in which L-Arg residues were replaced with D-Arg residues. Although there was no apparent difference in cellular uptake,4,8 a C14dR11 (myristoylated hendecaarginine, all Arg residues are in D configuration) peptide expressed enhanced cellular uptake capacity compared with its unmodified parent C14R11 peptide.6 Furthermore, the C14dR11 exhibited superior metabolic stability without adverse effect on cell viability and function. Here we describe a systemic evaluation of the various LOAPs by introducing different combination of D-Arg residues in the backbone, focusing on cellular uptake, cell toxicity, metabolic stability, and metabolic degradation patterns.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Lipo-oligoarginine peptides (LOAPs) synthesis

LOAPs (Table 1) were synthesized using Fmoc solid phase chemistry in an automatic peptide synthesizer (433A, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The detailed methods for fatty acid conjugation and labeling of Fluorescein isothiocynate (FITC) of the synthesized LOAPs have been described previously.6,12 Purification of the peptides was achieved by preparative RP-HPLC (Varian, Walnut Creek, CA) with Vydac 218TP C18 column (22 mm × 250 mm) by using a linear gradient of 10 – 60% B (A = 0.1% TFA in H2O; B = 0.1% TFA in ACN) over 60 min and a flow rate of 8 ml/min with 1 ml sample volume. The molecular mass of purified LOAPs was confirmed by ABI 4800 MALDI-TOF Proteomics Analyzer.

Table 1.

Sequences of synthesized LOAPs and oligoargines

| Peptide | a Sequence | Arg sequence |

|---|---|---|

| R7 | B(R)7K(FITC)-NH2 | RRRRRRR |

| R9 | B(R)9K(FITC)-NH2 | RRRRRRRRR |

|

| ||

| LOAP-1 | Lauroyl-B(R)9K(FITC)-NH2 | RRRRRRRRR |

| LOAP-2 | Lauroyl-B(r)9K(FITC)-NH2 | rrrrrrrrr |

| LOAP-3 | Lauroyl-B(r)5(R)4K(FITC)-NH2 | rrrrrRRRR |

| LOAP-4 | Lauroyl-B(R)4(r)5K(FITC)-NH2 | RRRRrrrrr |

| LOAP-5 | Lauroyl-B(r)4(R)(r)4K(FITC)-NH2 | rrrrRrrrr |

| LOAP-6 | Lauroyl-B(r)3(R)(r)3(R)(r)K(FITC)-NH2 | rrrRrrrRr |

| LOAP-7 | Lauroyl-B(r)2(R)(r)2(R)(r)2(R) K(FITC)-NH2 | rrRrrRrrR |

| LOAP-8 | Lauroyl-B(r)3(R)3(r)3K(FITC)-NH2 | rrrRRRrrr |

| LOAP-9 | Lauroyl-B(r)2(R)2(r)2(R)2(r)K(FITC)-NH2 | rrRRrrRRr |

| LOAP-10 | Lauroyl-B(rR)4(r)K(FITC)-NH2 | rRrRrRrRr |

B: β-alanine, r: D-arginine, FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate

2.2. Cell culture

Human Jurkat cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. Cells were grown on 75 cm2 culture flasks at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. To evaluate cellular uptake, and intracellular fate of LOAPs, Jurkat cells (3.5 × 105/ml) were incubated with 10 μM of LOAPs or R9 at 37°C for 10 min. Cells were washed with PBS thoroughly then incubated with 200 μl of trypsin-EDTA at 37°C for 5 min to remove cell surface-bound LOAPs. At the end of the trypsin treatment, 200 μl of culture medium was added to neutralize the protease.

2.3. Cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity assay was performed using the CytoTox 96® Assay (Promega, Madison, WI).6,12 In brief, 50 μl of culture medium containing 2 × 104 cells was dispensed into 96 U-bottom well plates and the volume was adjusted to an appropriate concentration with a final volume of 100 μl by adding LOAP solution. LOAP-induced toxicity was evaluated by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity released in the culture supernatant after 10 min exposure to LOAPs at 37°C.

2.4. Flow cytometry analysis

Jurkat cells (3.5 × 105/ml) were incubated with 10 μM of LOAPs at 37°C for 10 min, followed by PBS washes, and trypsin treatment. The treated cells were further incubated with 200 μl ice-cold propidium iodide (PI, 1μg/ml, Sigma) in PBS + 2% FBS to assess cell viability. The cells were filtered with Cup Filcons cell strainer (70 μm, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells stained with PI were excluded from the analysis. A total of 2 × 104 events were recorded using FACS LSR II (BD, San Jose, CA) and analyzed by WinMDI software (The Scripps Institute).

2.5. Metabolic stability of LOAPs

Metabolic degradations of FITC labeled LOAPs were monitored by analytical RP-HPLC (920-LC, Varian) equipped with fluorescence detector (excitation at 495 nm, emission at 521 nm). At each indicated time point (6, 24, 48 and 72 h), the whole culture medium containing the LOAPs was collected for HPLC quantification and mass analysis. The elution solvent A consisting of H2O (0.1% TFA) and solvent B consisting of acetonitrile (0.1% TFA). The linear gradient was 0 to 60% solvent B over 30 min. The flow rate was 1 ml/min with 10 μl sample volume. Collected allocations of FITC conjugated sequences (C-terminus) were identified by MALDI-TOF mass.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times, and the results were expressed as the mean ± SD. The statistical comparison of the cellular uptake and measurement was evaluated by paired-samples t-test and differences were considered significant at p < 0.05 between control and experimental groups.

3. Results

3.1. Quantification of cellular uptakes and release kinetics of LOAPs

LOAPs were synthesized with automatic solid phase synthesis plus manual modifying steps as previously reported.6,12 Lauroyl chloride (C12) was covalently conjugated to the N-terminus of the amidated oligoarginines and the fluorescent tag, FITC, was attached to the C-terminal lysine side chain (Table 1). Cellular uptake and release kinetics of the LOAPs were evaluated and quantified by measuring the fluorescence in Jurkat cells using flow cytometry (Fig. 1 and 2). All cells incubated with LOAPs showed high fluorescence intensity as compared to those incubated with control R9 peptide (11–31 folds, p < 0.012), and more than 95% of cells were labeled with LOAPs efficiently (Fig. 1B). By replacing L-Arg residues (LOAP-1) with D-Arg isomers (LOAP-2 to LOAP-10), the cellular uptake was significantly improved and the maximal fluorescence intensity was observed with LOAP-2 (p = 0.011 to LOAP-1). Even the least effective one, LOAP-4, showed 1.8-fold higher than it of LOAP-1 (p = 0.010). Surprisingly, the difference between LOAP-2 and LOAP-10 was not significant. Every D-Arg modified LOAP has better uptake efficiency than it of LOAP-1 (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Cellular uptake of LOAPs and R9 in Jurkat cells. Jurkat cells were incubated with 10 μM of LOAPs and R9 for 10 min at 37°C. The cells were then trypsinized, stained with PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry with 2 × 104 events. (A) The median fluorescence intensity of LOAP-1 was set as 1. (B) Flow cytometry histograms of FITC-unlabeled control, R9, and four LOAPs. % FITC was calculated by dividing gated cells (FITC internalized cells) with live cell region.

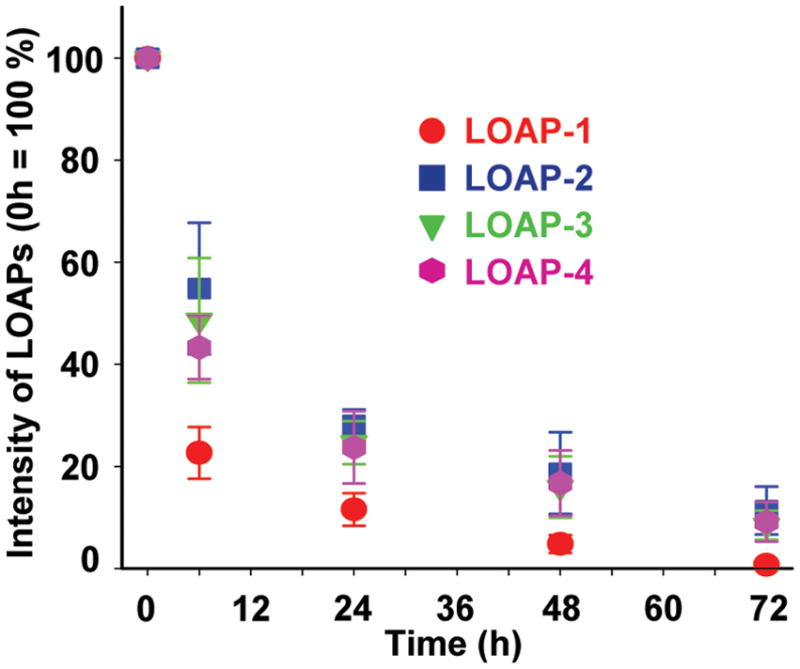

Fig. 2.

Release kinetics of LOAPs. Jurkat cells were incubated with 10 μM of LOAPs at 37°C for 10 min. Cells were then washed completely, further incubated with a fresh peptide-free culture medium for 6, 24, 48, and 72 h, and harvested for flow cytometry analysis. The fluorescence intensity of LOAPs at 0 h was set as 100 %.

The intracellular fate of LOAPs was studied by monitoring fluorescence signal changes over a period of 72 h (LOAP-1 to LOAP-4) (Fig. 2). In less than 6 h, 75% of LOAP-1 fluorescence signal was disappeared, and only 10 % of signal was retained after 24 h. On the contrary, near 50% and 20% of fluorescence intensities of LOAP-2, LOAP-3, and LOAP-4 were observed after 6 and 48 h, respectively.

3.2. Cellular toxicity

Although all LOAPs showed great cell loading capability, it is crucial to know whether the chirality difference could affect cell viability or not. Therefore, potential cellular toxicity was determined by measuring LDH release after exposure to LOAPs. Similar to R9, none of LOAPs caused significant LDH leakage (Fig. 3). This result indicates that LOAPs consisted of different combination of L- and D-Arg residues do not cause detrimental toxicity on cell viability and membrane integrity.

Fig. 3.

Toxicity of Jurkat cells incubated with various LOAPs. Cells were incubated with 10 μM of LOAPs at 37°C for 10 min. LOAPs-induced cell toxicity was evaluated by measuring LDH release assay. Data were normalized to the amount of maximum LDH released from the cultures treated with lysis solution alone and corrected for baseline LDH release from cultures exposed to buffer only. R9 peptide was used as a positive control.

3.3. Metabolic degradation patterns of LOAPs in Jurkat cells

The stability of LOAPs (LOAP-1 to LOAP-4) was first evaluated in cell free culture media containing 10% FBS. The culture media containing LOAPs were collected for HPLC analysis 6 h after incubation. Intact LOAP-1 gave one major peak with retention time (Rt) of 20.6 min, plus two tiny side-product peaks at 18.7 and 19.2 min, indicating that LOAP-1 was considerably stable in serum containing culture medium (Fig. 4A).8 Thereafter, LOAPs were incubated with Jurket cells in full culture medium for 10 min at 37°C, and the cells were treated with trypsin to remove surface bound LOAPs. After 6, 24, 48 and 72 h of incubation, the culture medium containing metabolites of each LOAP was collected and analyzed by HPLC (Fig. 4). The metabolites carrying C-terminal FITC-tag were followed by fluorescence detector. All investigated LOAPs showed two major peaks after 6 h (Fig. 4A). One group of peaks was eluted around 16 min (region 1), and the other group of peaks was located around 21 min (region 2). The retention time of region 2 is about the same of it of control LOAP-1, representing the intact LOAPs. No other metabolites could be found in the early Rt zone (t = 0 to 14 min) (Fig 4A inset). Surprisingly, it was found that the group 2 to group 1 ratio was about 2 for all tested LOAPs (Table 2), suggesting that LOAPs were hydrolyzed into similar metabolites at the similar rate. In order to identify the degraded metabolites, the Rt of R7 and R9 were determined (Fig. 4B). The Rt of group 1 matched well with R9 (Rt = 16.2 min) but not with R7 peptide (Rt = 15.5 min), indicating the group 1 peaks were various R9 peptides released from their parent LOAPs. Metabolites of LOAPs were also monitored after 24, 48, and 76 h to evaluate time dependent metabolic degradation pattern (Fig. 4C). There was no noticeable difference between metabolite patterns of LOAP-2 with time. The ratio of released metabolites from each LOAP was maintained at a constant level. Other LOAPs also showed roughly similar metabolic degradation patterns (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

HPLC profiles of LOAPs metabolites and intact peptides. (A) LOAP-1 (Black line) was incubated in the cell-free culture medium with 10% FBS for 6 h as the background reference. Culture media containing LOAPs (LOAP-1; red, LOAP-2; blue, LOAP-3; green, and LOAP-4; violet) were collected for HPLC analysis after 6 h incubation. (B) The chromatograms of intact R7 (blue) and R9 (green) peptides. (C) Metabolic degradation patterns of LOAP-2 at different incubation time. Cells were treated with 10 μM of LOAP-2 for 10 min at 37°C, washed completely, further incubated with a fresh peptide-free culture medium for 6, 24, 48 and 72 h, and whole culture medium was collected for HPLC analysis.

Table 2.

Ratio of metabolites obtained from HPLC spectra in Fig. 4A

| Peptide | Area (%)

|

Ratio (peak 1/peak 2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak 1* | Peak 2* | ||

| LOAP-1 | 64.39 | 33.01 | 1.95 |

| LOAP-2 | 59.08 | 32.27 | 1.83 |

| LOAP-3 | 56.17 | 29.07 | 1.93 |

| LOAP-4 | 62.56 | 30.14 | 2.08 |

: Peak1: Arg peptide, Peak 2: intact LOAPs. Mean ratio (peak 1: peak 2) = 1.95 ± 0.05

The molecular weight of peak 1 and peak 2 were determined and compared with it of R9 and LOAP-1 after 6h incubation (Fig 5). The mass of peak 2, [M+H]+ = 2195.6, matched with it of intact LOAPs in MALDI-TOF mass spectra, and the mass of peak 1, [M+H]+ = 2030.4, is close to it of R9 peptide, [M+H]+ = 2012.23. Metabolic products with similar mass were also found with other LOAPs (data not shown). The consistent results from HPLC and Mass analysis reveal that the acyl group was hydrolyzed easily; whereas, the oligoarginine peptides were relatively stable, so that no peptide fragments could be found.

Fig. 5.

MALDI-TOF analysis of the intact LOAP-1 and R9 peptide (A) and its metabolic fragments (B) after 6h incubation. Collected HPLC allocations of FITC conjugated fragments (C-terminus) were characterized by MALDI-TOF Mass. Mw of intact LOAP-1 and R9 were 2195.7 and 2012.23 ([M+H]+), respectively. The metabolite of intact LOAP-1 was identified as R9 peptide derivative (expected = 2012.23, observed = 2030.4). Schematic illustration showing the cleavage site in LOAP-1 is indicated at the bottom.

4. Discussion

Delivery of therapeutic agents into intracellular compartments has been impeded by cell plasma membrane. In order to overcome this impermeable barrier, therapeutic agents have been associated with CPPs which across the lipid bilayer of cell without compromising of normal cellular function. Several studies have demonstrated that lipophilic moiety conjugated CPP such as stearlylated arginine-rich peptides,13–16 lipid conjugated cationic peptides,17,18 and myristylated proline-rich peptides19 delivered cargo molecules efficiently. However, one major drawback in using CPPs as delivery vectors is their poor metabolic stability, because most CPPs are prepared with natural amino acids. Structurally modified CPPs, consisted of D-amino acids and/or β-peptides, have been developed to overcome these problems.6,8,12 A new approach was employed to reduce proteolytic degradation of CPPs by introducing N-terminal fatty acylation, C-terminal amidation, unnatural D-Arg and β-Ala insertion in the lipo-oligoarginine peptide template, wherefore intracellular metabolic stability of myristoylated D-hendecaarginine (C14dR11, all D-Arg residues) was improved dramatically.6 Interestingly, the cellular uptake of C14dR11 was also increased compared with the normal myristoylated L-hendecaarginine (C14R11, all L-Arg residues).4,5

In the present study, the cellular uptake, intracellular fate, cell toxicity, metabolic stability, and metabolic degradation pattern of LOAPs were systemically evaluated by introducing various combinations of D-Arg residues into the template backbone. It has been reported that translocation of cationic CPPs starts from electrostatic interaction of CPP positive residues with negatively charged glycosaminoglycan presented in the extracellular matrix of cell surface. The CPPs then associate with lipophilic regions of cell membrane and gain access to intracellular compartments by energy dependent endocytosis.20–22 Prior study of cellular internalization of LOAPs at 37 and 4°C has showed that most of the LOAPs were entered cells through the energy dependent pathway.6 On the other hand, several studies have showed that cationic CPPs containing hydrophobic molecules and arginine-rich peptides were internalized by non-endocytic pathway.23–25 It was also reported that the internalization efficiency of tat peptides was increased when all L-amino acids were replaced with their enatiomers (D-amino acids). Similarly, D-Arg CPPs were more effective in entering plasma membrane of Jurkat cells than L-Arg CPPs.4–6 The aforementioned findings are consistent with our result that cellular uptake efficiency of LOAPs (LOAP-2 to LOAP-10) was prominently increased by replacing L-Arg with D-Arg residues. Consequently, the receptor-mediated endocytosis could not represent the cellular uptake mechanism of LOAPs, since most receptors do not recognize D-isomers. The uptake efficiency of all D-arginine containing LOAPs was found to be similar. Variation was observed within LOAPs, but the difference was not significant. The cellular uptake capacity derived by median fluorescence intensity of LOAP-1 (557 AU) was significantly different from LOAP-2 (1778 AU) and other LOAPs; however, the number of FITC containing cells (% FITC) was similar for LOAP-1 and LOAP-2 (98 % vs. 99 %) (Fig. 1B). This result suggested that all LOAPs enter cells evenly, but at different efficiency. The release kinetics of LOAPs (LOAP-1 to LOAP-4) was monitored for 72 h. It was found that the fluorescence intensity in the LOAP-1 treated cells was declined sharply, while the other LOAPs which contained D-Arg residues had retained their fluorescence signals relatively long.

Another critical question is whether LOAPs can freely move into and out of cells. In one prior report, cells were treated with a N-terminal tagged tat peptide for 3 h, and then cultured with a fresh tat peptide-free medium.23 During incubation, fluorescence intensity was gradually decreased and totally diminished after 24 h. The culture medium was analyzed to understand whether the disappearance of fluorescence intensity was caused by the leakage of the intact tat peptide or partially degraded peptides. By HPLC, only degraded metabolites were detected in the collected medium, indicating that decreased fluorescence intensity was a result of peptide degradation, not efflux of the intact tat peptide. It is well known that Tat protein, capable of penetrating through the cell membrane, is released from the cells and then enter neighboring cells during HIV-1 infection or after infection.26,27 These results indicate that tat peptides can enter cell membrane effectively but it was degraded before transverse out of the cells. In a separate study, chemically modified pVEC peptides were used to study cellular stability.8 It was found that the D-analog pVEC peptide was stable in culture media supplemented with10% FBS, and the C-terminal Lys residue of normal pVEC was easily degraded into the culture medium.

The metabolic stability of four different LOAPs (LOAP-1 to LOAP-4) was evaluated in the extra- and intracellular proteolytic environments using two analytical methods, RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF MS. LOAP-1, composed of all L-amino acids, has maintained its original HPLC elution pattern in the cell-free culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS at least for 6 h, indicating that the LOAPs are stable in culture medium. To evaluate intracellular stability, Jurkat cells were incubated with LOAPs for 10 min, and then the culture medium was replaced with a fresh medium. After 6, 24, 48, and 72 h of incubation, both degraded metabolites and intact LOAPs were found in the culture medium and a considerable amount of fluorescence signal was detected inside of the cells during experiments as shown in Fig. 2 and 4. The results indicated that a portion of intact LOAPs and their metabolites were released from cells. The degraded metabolites were identified mainly as R9 residues, suggesting that a metabolic cleavage was occurred between lauroyl chain and non-natural β-Ala residue. Unexpectedly, regardless of types of LOAPs, the ratio between intact LOAPs and deacetylated peptide was all about 1:2. Although internalized CPPs have been reported to be sensitive to peptidase,8,9,11,23 none of the hydrolyzed peptide fragments were found in this study. The C-terminal amidated Lysine(FITC) residue plus the N-terminal non-nature β-Ala residue might have attributed to this unusual resistance to proteolysis.

Interestingly, the cell release study showed that the D-Arg residues containing LOAPs (LOAP-2 to LOAP-4) had longer retention time than it of LOAP-1. At 24 hrs, only 12% of LOAP-1 was remained within cells, while LOAP-2 to LOAP-4 maintained at about 23–28% level. Previously we have found that a much better retention, 85% at 24 hrs, could be achieved when the lipid chain and peptide chain were slightly increased to C14 and R11 (C14dR11).6 However, further lengthen the lipid chain caused significant toxicity.

In conclusion, the results presented in this study provide a better understanding about cellular uptake mechanisms and metabolic stability of amphiphilic LOAPs. Although fluoroscein was used as a payload to study the cellular translocation and intracellular distribution, a variety of drugs, macromolecules, or proteins can potentially be incorporated onto the optimized LOAPs. Therefore, the approach described here may represent an enabling strategy in CPP labeling technology for in vivo imaging of cell trafficking needed for long term investigation and therapeutic potentials based on the cellular delivery of cargo materials to a variety of phamacological treatments.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH CA135312, CA114149 and CA126752. We thank Catherine Chen (Rice University) for peptide preparation.

References

- 1.Tung CH, Weissleder R. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:281–294. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nori A, Jensen KD, Tijerina M, Kopeckova P, Kopecek J. Bioconjug Chem. 2003;14:44–50. doi: 10.1021/bc0255900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao M, Kircher MF, Josephson L, Weissleder R. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13:840–844. doi: 10.1021/bc0255236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wender PA, Mitchell DJ, Pattabiraman K, Pelkey ET, Steinman L, Rothbard JB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13003–13008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell DJ, Kim DT, Steinman L, Fathman CG, Rothbard JB. J Pept Res. 2000;56:318–325. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2000.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JS, Tung CH. Molecular bioSystems. 2010;6:2049–2055. doi: 10.1039/c004684a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garner P, Sherry B, Moilanen S, Huang Y. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2001;11:2315–2317. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elmquist A, Langel U. Biological chemistry. 2003;384:387–393. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trehin R, Nielsen HM, Jahnke HG, Krauss U, Beck-Sickinger AG, Merkle HP. The Biochemical journal. 2004;382:945–956. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rennert R, Wespe C, Beck-Sickinger AG, Neundorf I. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2006;1758:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foerg C, Weller KM, Rechsteiner H, Nielsen HM, Fernandez-Carneado J, Brunisholz R, Giralt E, Merkle HP. The AAPS journal. 2008;10:349–359. doi: 10.1208/s12248-008-9029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham W, Kircher MF, Weissleder R, Tung CH. Chembiochem. 2004;5:1148–1151. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khalil IA, Futaki S, Niwa M, Baba Y, Kaji N, Kamiya H, Harashima H. Gene Ther. 2004;11:636–644. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Futaki S, Ohashi W, Suzuki T, Niwa M, Tanaka S, Ueda K, Harashima H, Sugiura Y. Bioconjug Chem. 2001;12:1005–1011. doi: 10.1021/bc015508l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mae M, El Andaloussi S, Lundin P, Oskolkov N, Johansson HJ, Guterstam P, Langel U. J Control Release. 2009;134:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehto T, Abes R, Oskolkov N, Suhorutsenko J, Copolovici DM, Mager I, Viola JR, Simonson OE, Ezzat K, Guterstam P, Eriste E, Smith CI, Lebleu B, Samir El A, Langel U. J Control Release. 2010;141:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koppelhus U, Shiraishi T, Zachar V, Pankratova S, Nielsen PE. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1526–1534. doi: 10.1021/bc800068h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niidome T, Urakawa M, Takaji K, Matsuo Y, Ohmori N, Wada A, Hirayama T, Aoyagi H. J Pept Res. 1999;54:361–367. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.1999.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez-Carneado J, Kogan MJ, Van Mau N, Pujals S, Lopez-Iglesias C, Heitz F, Giralt E. J Pept Res. 2005;65:580–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2005.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki T, Futaki S, Niwa M, Tanaka S, Ueda K, Sugiura Y. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:2437–2443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Console S, Marty C, Garcia-Echeverria C, Schwendener R, Ballmer-Hofer K. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:35109–35114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuchs SM, Raines RT. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2438–2444. doi: 10.1021/bi035933x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Futaki S, Suzuki T, Ohashi W, Yagami T, Tanaka S, Ueda K, Sugiura Y. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:5836–5840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puckett CA, Barton JK. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131:8738–8739. doi: 10.1021/ja9025165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fretz MM, Penning NA, Al-Taei S, Futaki S, Takeuchi T, Nakase I, Storm G, Jones AT. The Biochemical journal. 2007;403:335–342. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frankel AD, Pabo CO. Cell. 1988;55:1189–1193. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ensoli B, Buonaguro L, Barillari G, Fiorelli V, Gendelman R, Morgan RA, Wingfield P, Gallo RC. Journal of virology. 1993;67:277–287. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.277-287.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]