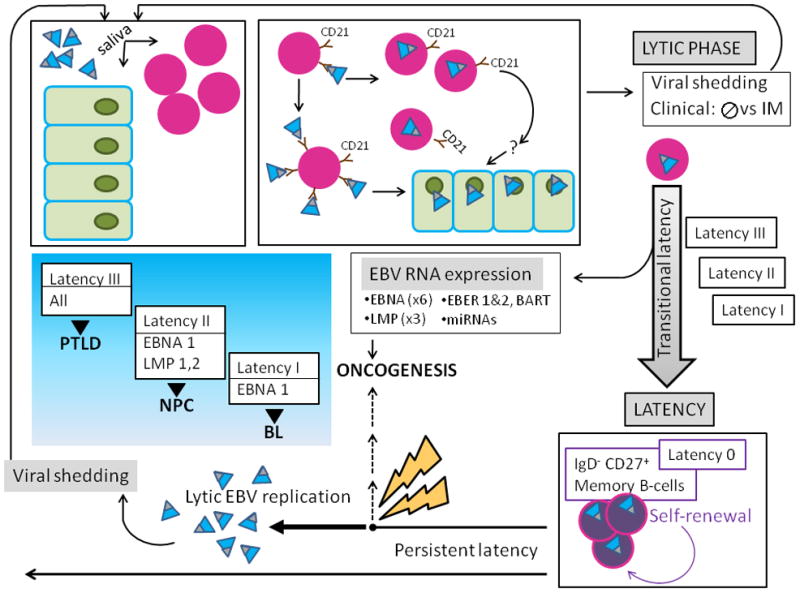

Figure 6. Schematic of EBV-host interactions.

A) EBV (teal virions with black tip) is acquired orally, and targets B-cells (lavender nucleated circles) and permissive epithelial cells of the oral pharynx (green). The major EBV envelope glycoproteins gp350 and gp220 (black tip) interact with complement receptor CD 21 (brown) on the surface of naïve resting B-lymphocytes, leading to viral binding. Additional EBV B-cell interactions involving fusion proteins and HLA class II molecules (not shown) lead to virus-cell fusion and EBV internalization. EBV bound to the B-cell surface likely allows for its transfer to orophangeal epithelial cells. The initial lytic viral reproductive phase may be asymptomatic (usually) or may manifest clinical symptoms and is termed infectious mononucleosis (IM). During the lytic phase, virus is shed via the saliva and can infect naïve hosts.

B) After the initial lytic phase, EBV evades host immunosurveillance to achieve persistence though “translational latency”, the tightly regulated selective expression of viral latent proteins and of non-coding RNAs. The former include six Epstein-Barr virus Nuclear Antigens (EBNAs) (1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C, and LP) and three integral Latent Membrane Proteins (LMPs) (1, 2A, and 2B). The latter include EBERs (1 and 2), small non-coding RNAs abundantly expressed in latently infected EBV cells and multiple microRNAs, encoded by two transcripts (in the BART and BHRF1 loci), that contribute to EBV-associated cellular transformation. Three distinct “transitional” EBV latency programs (Latency I, II, and III) are characterized by specific gene expression profiles that allow for establishing latency and enhancing cell survival and proliferation. After the initial lytic phase, EBV replicates as an episome, in tandem with the host cell genome. EBV employs host cell-driven DNA genomic methylation and modulation of NF-κβ activity, and Notch signaling pathway manipulations (not shown) to establish true latency (Latency 0) in resting memory B-cells (purple circles), with highly restricted EBV gene expression. Non-pathogenic and invisible to the host immune system, Latency 0 EBV persistently populates memory B-lymphocytes. In the course of the latently infected hosts’ life, episodic disruptions of latency occur (depicted as ‘STRESS’ and yellow bolt), resulting in EBV replication and viral shedding with potential spread to other hosts. Latent EBV also can contribute to several cancers (dashed line), including lymphomas such as Burkitt’s Lymphoma (BL), and Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma (NPC). Exogenous immunosuppression may result in Post-Transplantation Lymphoproliferative Disorders (PTLD). The emergence of malignancy appears to require interactions of co-factors, for example P. falciparum in BL, and individual host characteristics, including HLA type in NPC.