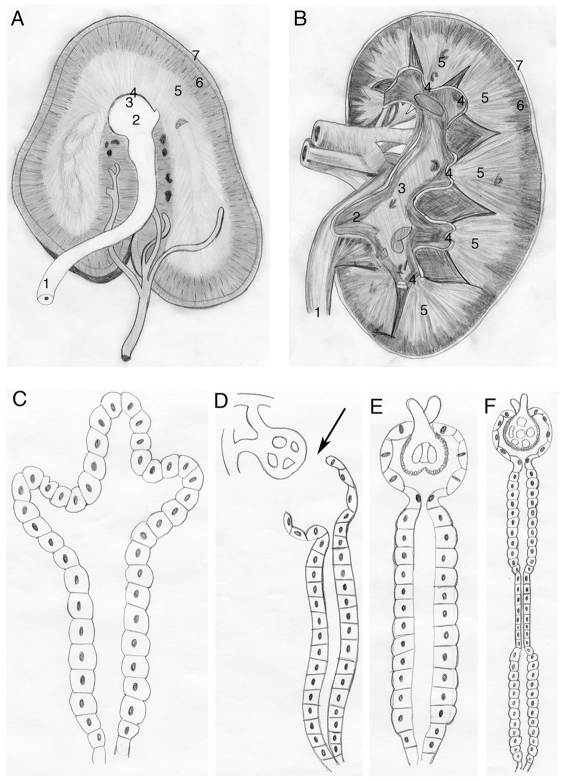

Fig. 1.

Kidney diversity. (A,B) Two examples of structural diversity seen in mammalian kidneys. Specific anatomical structures of these examples are as follows: ureter (1), pelvis (2), calyx (3), papilla (4), medulla (5), cortex (6) and fibrous capsule (7). The horse kidney (A) demonstrates a kidney type in which the papillae (4) and calyxes (3) fuse to form a single structure that projects into the pelvis (2) (Frandson et al., 2009). Rather than the familiar human (B) ‘bean’-shaped kidney, the two poles extend to form a ‘crest kidney’. The human kidney (B) demonstrates multiple papillae (4), and calyxes (3) merging into a single pelvis (2). This illustrates kidney adaptation beyond the single papilla. See Dyce et al. and Oliver (Dyce et al., 1995; Oliver, 1968). (C-F) Comparing three examples of aquatic pronephroi (C-E) with the mammalian nephron (F) to illustrate nephric structural diversity. Aglomerular nephrons (C) are seen in subsets of marine teleosts, including Opsanus tau and Lophius piscatorius. This type of nephron filters via secretion into the ductal system. (D-F) Example of non-integrated (D) versus integrated (E,F) glomerular kidneys. (D) A glomerular-filtering nephron whose tubules and ducts are separated by the coelom (arrow). An example of this type of kidney is seen in Xenopus embryos (Dressler, 2006). The zebrafish embryo nephron (E) consists of a glomerulus integrated into pronephric tubules and ducts, topological architecture similar to that seen in humans (F). When comparing E to F, however, the separate sections noted in mammalian ducts (F) cannot be visually distinguished in the zebrafish pronephros (E). See Vize and Smith (Vize and Smith, 2004).