Abstract

Background

Cancer Care Ontario’s Program in Evidence-Based Care (pebc) was formalized in 1997 to produce clinical practice guidelines for cancer management for the Province of Ontario. At the time, the gap between guideline development and implementation was beginning to be acknowledged. The Program implemented strategies to promote use of guidelines.

Methods

The program had to overcome numerous social challenges to survive.

Prospective strategies useful to practitioners—including participation, transparent communication, a methodological vision, and methodology skills development offerings—were used to create a culture of research-informed oncology practice within a broad community of practitioners.

Reactive strategies ensured the survival of the program in the early years, when some within the influential academic community and among decision-makers were skeptical about the feasibility of a rigorous methodologic approach meeting the fast turnaround times necessary for policy.

Results

The paper details the pebc strategies within the context of what was known about knowledge translation (kt) at the time, and it tries to identify key success factors.

Conclusions

Many of the barriers faced in the implementation of kt—and the strategies for overcoming them—are unavailable in the public domain because the relevant reporting does not fit the traditional paradigm for publication. Telling the “stories behind the story” should be encouraged to enhance the practice of kt beyond the science.

Keywords: Knowledge translation challenges, cancer guidelines, Cancer Care Ontario

1. INTRODUCTION

The editorial that introduced this series distinguished between the “science” and the “practice” of knowledge translation (kta), implying that important kt experiences stay hidden because their publication does not “conform to the traditional research paradigm” 1. In that spirit, this article presents the story behind the early days of the Program in Evidence-Based Care (pebc), Cancer Care Ontario’s guideline initiative. The story is a personal commentary narrated by the program’s founding director, and circulated for comment to early program participants.

The pebc (https://www.cancercare.on.ca/cms/one.aspx?pageId=7582) was established to meet Cancer Care Ontario’s requirement to develop clinical practice guidelines (cpgs) as one condition of continued funding. At the time, the limitation of guidelines as kt vehicles was beginning to be recognized, prompting the Program to institute strategies beyond dissemination to promote their use. The implementation strategies described in the rest of this article together qualify pebc as a kt initiative.

“The Story” describes the early years of the initiative, providing insights into the barriers faced and the responses to them. Its intent is to meet the challenge to tell honestly about issues faced that otherwise might not surface. Where “The Story” ends, others have since taken the Program much further: https://www.cancercare.on.ca/toolbox/qualityguidelines/pebc/.

2. THE STORY: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

In 1994, Cancer Care Ontario embarked on cpg development through expert panels within Ontario’s provincial cancer system. Development of cpgs came at the direction of the organization’s funder, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, which made their development a condition of continued funding.

Initially, province-wide panels corresponding to cancer disease sites and consisting almost exclusively of oncologists were assembled to develop cpgs. They approached the task using informal consensus, without specific tools. Then, one cancer centre—at the instruction of then-director and regional vice president, Dr. Mark Levine—declined participation because of concern about the lack of commitment to evidence-based methods.

The nonparticipating centre, of which I was a senior member, subsequently conducted a process within its region to meet the parent organization’s goals through an evidence-based model. That process involved having disease site groups develop clinical recommendations on priority clinical conditions of their own choice. The groups were provided with library science support and were asked to present their experiences to a broad regional audience at monthly evening sessions. Sessions were observed by a selected group of research design methodologists, including oncologists, an oncology nurse, internal medicine and health informatics specialists, library scientists, clinical trialists, and a health economist. After 12 months, the team used what it had learned from its observations to design a structured approach to the evidence-based development of cpgs on cancer within the context of a cancer system 2,3.

Meanwhile, the province-wide expert panels were developing their consensus guidelines. Approximately 10 cpgs were submitted from the various panels. Cancer Care Ontario’s organizational leaders (vice presidents and the president)—and, to their credit, the panel chairs—were disappointed in the quality of the cpgs produced. Loose connections between recommendations and evidence, highly variable cpg formats, variation in comprehensiveness, and variable attention paid to the research evidence behind recommendations were some of the major concerns. As a result, the group from the nonparticipating centre was invited to meet provincial panel chairs to assist in improving the process, with a commitment to an evidence-based approach.

The group brought with them a slide presentation of the methodology they had developed 2, but they first invited the panel chairs to present their experiences, including frustrations, barriers, and facilitators. Experiences were consistent across panels. Only then did the group present its model, demonstrating how the model features addressed each concern that had been raised.

Four features of the model addressed common frustrations:

Use of priorities for topic selection, rather than across-the-board coverage of all disease sites—that is, panel control over agenda-setting. The term “priorities” refers to the disease site panel’s judgment about topics of importance from the clinical, treatment access, and cost perspectives.

Framing of guidelines around specific clinical questions rather than an attempt to comprehensively cover a disease site—that is, a narrower focus for each guideline. For example, instead of one comprehensive breast cancer cpg, disease site panels would narrow the frame of reference: adjuvant therapy for stage ii node-positive postmenopausal women, for instance.

Provision of a guiding framework and organizational structure for the cpgs.

Negotiation of administrative policy support to reassure panels that clinical recommendations would be respected at the board level.

The members of the group from the nonparticipating centre were then appointed to lead the next phase of cpg development with support from the panel chairs and with adequate funding. By 1997, that informal charge had been converted to a new funded program—the pebc—and within 3 years, the budget had been more than quintupled.

The pebc was conceptualized as more than a cpg development program. It also focused on implementation strategies now recognized as consistent with the field of kt. Specific strategies designed to enhance engagement and support included mentoring the expert panel members; addressing the urgencies of policymakers with respect to emerging evidence and advocacy; creating educational tools; engaging in international collaborations 4–6; and convening workshops for skills transfer in literature search, evidence synthesis, and the use of meta-analytic software. The pebc came to involve multiple academic disciplines, community-based professionals, and community representatives (laypeople).

The pebc philosophy embraced “bottom-up” engagement in the process of evidence synthesis and interpretation, and of review and development of recommendations by those expected to apply them. The process was facilitated by a trained methods resource group (librarians, methodologists, oncologists) attached to panels and by peer support coming from mentors chosen for their enabling style. Using the kt principle of pilot-testing with end users, an inventory of all provincial-based oncologists and a survey tool were developed to allow practicing oncologists, whether part of the formal cancer system or not, to review draft guidelines before release, and panels were expected to document and to respond to the concerns expressed in the feedback in a dedicated section within each cpg 7,8.

3. BEHIND THE STORY: KT CHALLENGES

Certain challenges were anticipated and led to proactive kt strategies (Table i). Others were not anticipated and required reactive strategies in response (Table ii).

TABLE I.

Proactive knowledge translation strategies

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Fostering a sense of community | |

| Publication of a regular newsletter updating panel participants on learning opportunities, progress of other panels, and general information in cancer guideline development | |

| Giving back | |

| Offering educational workshops, led by experts, upgrading the methodology skills of panel members: literature search, systematic review design and interpretation, meta-analysis software use, critical appraisal methods, consensus methods, and evidence-based principles | |

| Methodologic peer mentorship | |

| Panel meetings were facilitated by an oncologist with special skills in research design methods and an enabling style | |

| Structured guidance and social strategies | |

| Structured methods were used to guide panel meetings; features included “time outs” to allow panels to reflect on behaviours and learning opportunities arising from discussions—for example, a predictable comment early in initial meetings was that participants were “experts,” knew the literature and therefore didn’t need a systematic approach; by allowing the discussion to proceed, we were able in each instance to show how each panel member had a different “biopsy” of “the body of evidence,” which they interpreted differently, demonstrating explicitly the need for a systematic approach | |

| Facilitation through staff support | |

| Each panel was supported with a dedicated research coordinator skilled in library science or research design methods at the Masters level as part of a Methods Resource Group (supported by Program funding) | |

| Empowerment through choice | |

| Panels were offered flexibility in topic selection and in the order in which they addressed each topic according to specific priority criteria | |

| Realistic goal-setting | |

| Panels were charged to address narrowly defined clinical questions that could result in the completion of a useful clinical practice guideline within a reasonable time frame | |

| Instilling pride | |

| We benefited from intimate collegial access to those who popularized or originated the critical appraisal and evidence-based movements, together with access to trained staff associated with those fields; this access allowed for the design of products of world-class quality as a means of attracting commitment and support | |

| Negotiating support and fostering trust | |

| The Program negotiated with the parent organization to ensure that clinical recommendations of panels were respected at the management and policy levels | |

TABLE II.

Reactive strategies to barriers in early phases of knowledge-translation programming

| Barriers | Responses |

|---|---|

| Academic rivalry Five university-based academic health science centres with medical schools, often with inter-organizational competition; the Program in Evidence-Based Care (pebc) was placed within one of those universities Some academic department heads discouraged participation, indicating that Program contributions would not qualify for academic credit Program leaders accused of benefitting their own careers at the expense of panel members’ work |

|

| Availability of oncologists’ time to participate Among the most difficult challenges, especially for community-based oncologists paid fee-for-service |

|

| Time taken to produce documents for decision-making Most guideline development programs that focus on evidence-based methods learn that rigorous attention to methodology requires time that often fails to meet expectations of clinical and management/policy decision-makers alike, thus threatening the credibility and utility of the Program |

|

| Emerging expectations of the advocacy community At the time, the advocacy movement was gaining momentum, and even peer-review grants panels were including community representatives. There was pressure to complement what was perceived as the “sterility” and elitism of the evidence-based paradigm to include other factors such as patient and system circumstances and patient preferences into clinical recommendations |

|

3.1. Proactive Strategies

Early on, it was recognized that the initiative would need to go beyond cpg development; implementation strategies across an entire jurisdiction with a population more than 10 million would be required. To that end, a sense of identity would have to be created among Program participants, and those participants would have to be offered something in return. (Early on, a significant proportion of practitioners remained leery of cpgs.)

To begin, the Program had one research assistant, a faculty leader, and a panel of oncologist mentors from various regions of the Province of Ontario who were formally trained in research design. When the Program began, the literature on kt identified certain strategies, alone or in combination, as being modestly effective in influencing clinical behaviour:

Targeting opinion leaders

Academic detailing

Involvement of the community (participation)

Patient-mediated tools

Audit and feedback

Point-of-care and computer-assisted reminders

Since then, the science of kt has evolved 9–14.

To enhance uptake of guidelines, the Program adopted other proactive strategies including “giving back” to participants (educational events and skills transfer), regular newsletters to foster a sense of community, a commitment to the quality of cpgs to instill pride and to capture the support of skeptics, and active facilitation through the Methods Resource Group of trained staff in recognition of the limited time available to clinical participants and the social nature of practice change 14. “Facilitation” included undertaking literature searches, entering data into tables, using software to do the meta-analyses, preparing the guideline draft, coordinating community surveys, and organizing panel meetings.

In essence, conditions for well-functioning “communities of practice” were created at the community–academic interface. The communities-of-practice model tends to encourage loyalty of members to the group and a sense of identity that fosters effective participation and productivity 15.

3.2. Reactive Strategies

Not every threat to the Program’s success and credibility could be anticipated. As the Program evolved, several issues arose requiring a direct and effective response:

-

The Program was born within a competitive environment involving five academic health science centres, each with a cancer centre in its region. The Program took up the time of participating oncologists who were clinically busy and who had cross-appointments to academic departments within faculties of medicine. The cancer centres highly valued academic productivity. As a result, several oncologists indicated that they could not participate because their department head did not consider their Program contributions worthy of academic credit—either because the head undervalued such activity (evidence synthesis and cpg development) as a legitimate scientific or research pursuit, or because the program was housed within a competing institution. At the time, the evidence-based movement was still controversial.

In response, the Program- negotiated with a peer-reviewed Canadian oncology journal (now out of print) to have the cpgs published. In addition, Program staff prepared cpgs for publication by other peer-reviewed journals.

- negotiated with the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada to provide continuing medical education credits for participants.

- focused on instilling pride and gaining credibility through the production of high-quality products—for example, by having its guidelines accepted and posted at the National Guideline Clearinghouse managed by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (http://www.guidelines.gov/).

-

The rivalries associated with a competitive academic environment provoked accusations that Program leaders were advancing their own academic careers at the expense of the work of others.

In response,- Program leaders agreed to decline co-authorship for cpgs to which they did not make the most substantive contribution.

- the Program ensured that panel members making significant contributions earned academic credit through authorship, a strategy that was especially effective for gaining the support of community-based participants and other health professional groups.

-

Decision-makers at the management and policy levels, and clinicians who desired access to new treatments, were concerned that the time taken for an evidence-based approach would not yield a cpg within a reasonable period.

In response, the Program- developed a methodology framework for “advice documents” that short-circuited the elaborate process of systematic reviews, while maintaining a credible level of methodologic rigour 16.

- The early methodology for advice documents is not available, because it has been considerably improved since the early years. A full presentation of the Program’s current methods can be found at https://www.cancercare.on.ca/cms/one.aspx?pageId=10179. Ultimately, the systematic reviews were done and the full cpgs were completed, but the process nevertheless provided guidance for policymakers in “real time.”

- developed a formal “horizon-scanning” approach to anticipate emerging hot topics to which a quick response might be needed.

- Horizon-scanning applied mainly to anticipated conference presentations—for example, those at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting—and to media coverage of new and expensive cancer drugs. Horizon-scanning was instituted through monthly teleconferences between panel chairs and a dedicated research coordinator, who added such items to each monthly agenda. As an issue was identified (for example, through knowledge of progress in various clinical trials, discussions with industry, and presentations at major conferences), one member of the panel and the chair worked with the research coordinator to assemble the material for a draft cpg to be ready when needed. Subsequently, over a 4-year period, the Program had a usable cpg ready when 13 of 15 “new cancer drug” stories emerged in the press.

- Development of the Program coincided with acceleration of the cancer patient advocacy movement. Empowerment of the lay community was gaining momentum, and credible peer-review granting agencies were including community representatives on scientific review panels.

- The Program responded by inviting the Canadian Cancer Society to identify volunteer representatives to sit as members of cpg panels and other Program committees. The strategy included development of orientation materials and workshops.

3.3. Relevance to KT and KT Theory

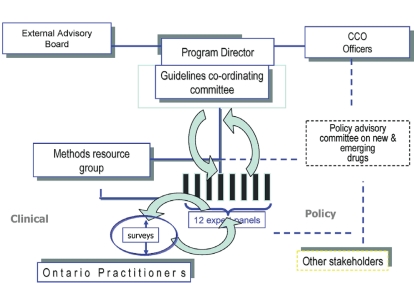

The pebc developed with a conscious agenda to go beyond cpg development toward implementation. Through panel chair and membership selection, opinion leaders and community-based practitioners were recruited. The Program attempted to instill a sense of belonging and trust among participants through transparent processes such as pilot-testing with end users, making a panel’s responses to feedback explicit within the cpgs, and implementing a clear organizational and reporting structure (Figure 1). Because of how the Program was situated, it aimed to influence the practice and the policy sectors alike, meaning that the Program met the criteria of a kt initiative.

FIGURE 1.

Initial structure of the Program in Evidence-Based Care and reporting relationships. The “expert panels” refers to the provincial disease site groups. They engage the community of practitioners through regular surveys conducted by the Methods Resource Group to obtain feedback on draft guidelines. The activities of the panels are overseen by the Program Director and the Coordinating Committee, who review all clinical practice guidelines produced and make recommendations for improvement before the guidelines are officially approved by the Program. The Program Director has access to senior decision-makers within the organization and is advised by an external Advisory Group. Note the Program’s link to a Policy Advisory Committee.

Useful insights into the history and theoretical models that inform kt are found in published reviews of the kt literature (for examples, see Kitson et al., 2008 14; Sudsawad, 2007 17; Oborn et al., 2010 18; Estabrooks et al., 2006 19; Graham and Tetroe, 2007 20; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2009 21; and Graham et al., 2006 22). The potential importance and effectiveness of the “communities of practice” social learning model in supporting the implementation of evidence into practice has been demonstrated in the mental health sector 23. The Program’s approach was heavily influenced by the teachings of Jonathan Lomas, with whom the Program had a close collegial relationship, and by his “coordinated implementation model” of kt 24. Readers desiring more information on social learning theory and the coordinated implementation model can refer to the citations provided in the references.

This kt initiative was pursued without the benefit of a formalized, universally accepted, or unifying theoretical kt framework. A systematic review of kt, social networking, or the organizational literature was not undertaken before the Program started. In other words, we “muddled through” 25. However, the Program described here was informed by generous exposure to an academic environment rich in evidence-based and kt expertise. In fact, one reviewer of the Program’s first published paper 2 asked whether the experience could have happened anywhere else—the point being that the research and practice environment was primed and in a state of “readiness” for the approach. The comment might be interpreted as a compliment or a question about the transferability of the proposed model. The program did learn of a remarkably similar cancer guidelines program at a similar stage of development being conducted in Lyon, France 26, which led to productive collaborations 27.

4. EVALUATION

Is there evidence that the Program is effectively meeting its objectives?

By their nature, cpgs are kt objects. They meet the criteria of “boundary objects”: tools intended to bridge the various communities between which knowledge is to be transferred 28,29. Evidence-based cpgs are, by definition, a bridge between research and practice, or what Graham prefers to call “action” 22. In this case, recall that the Program originated at the behest of policymakers, one of the four communities involved (researchers, practitioners, policymakers, and patients).

From the perspective of policymakers, the Program has been successful, in that cancer system funding, which was contingent on cpg production, did flow. More telling was informal feedback from government contacts that cancer system recommendations based on the Program’s guidelines were highly valued because of the rigour of the methodology, international credibility, and the inclusiveness of the process. As a result, Program recommendations were approved for funding more quickly than otherwise would have been the case (personal communication), suggesting that the policymakers felt that their decisions were well informed by the process.

Health care practitioners gave anecdotal feedback that “panel meetings are the highlight of my professional activities,” and that “the Program has raised the bar of cancer care in the province.” But what everyone wants to know is the “bottom line”: Has the Program improved practice (that is, patterns consistent with evidence) or patient outcomes? Has it reduced costs?

The Program has itself participated in evaluative efforts, and it has encouraged other independent researchers in the province to take up the evaluation challenge. Cancer Care Ontario’s Cancer Quality Council (http://www.cancercare.on.ca/cms/One.aspx?portalId=1377&pageId=7358) reported on the concordance between lung cancer guidelines and practice, observing that 51% of patients with stage ii or iiia non-small-cell lung cancer received guideline-recommended adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection. For those with stage iiia and b disease not resected, only 27% received treatment consistent with guidelines 30.

A two-province study—in Newfoundland and Labrador, and Ontario—of adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stages i–iii colon cancer 31 observed complete concordance with guidelines for stage i disease, and 87% (Newfoundland and Labrador) and 94% (Ontario) concordance with guidelines in stage iii disease. In the more controversial area of stage ii disease, the use of adjuvant therapy was, as expected, more variable. In a single-centre study, Major and colleagues 32 observed 95% concordance for the use both of adjuvant chemotherapy and of specific regimens for stage iii disease. Again, for stage ii disease, 80% of “high risk” patients received adjuvant treatment consistent with guideline-recommended options, and only 4% of low-risk patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, consistent with the guideline.

Of particular interest, Biagi et al. reported province-wide adherence to guidelines for stage iii colorectal cancer across eight cancer centres, together with reasons for non-adherence 33. Overall, 65% of patients received treatment consistent with guidelines (range across centres: 47%–72%). But, of the practitioners not treating 132 patients according to guidelines, nearly all had good reasons for the departure, including documented comorbidity, patient choice, diagnostic uncertainty, and clinical trial enrollment. This study suggests caution with respect to judgments of clinical performance based on patterns of practice and to assumptions about reasons for non-adherence to cpgs.

None of the foregoing studies was designed to allow for inferences about the causal relationship between guidelines and practice, but they are useful for generating hypotheses, promoting reflective practice, and informing quality improvement activities. Systematic reviews of properly designed prospective studies of the influence of guidelines and similar interventions suggest that these efforts are of at least modest effectiveness in influencing practice and possibly outcomes 34–36.

Regardless of whether the Program’s efforts have caused practice changes or improved outcomes, regionally relevant guidelines serve as a benchmark against which to evaluate existing practice patterns and outcomes.

5. DISCUSSION

The early history of the development of a kt initiative that began as a cancer cpg development mandate provides insights into the barriers faced in implementing practice and policy changes informed by research evidence. The Program was designed as it was becoming clear that cpg development and passive dissemination were necessary but insufficient for guideline use and practice change. In retrospect, the Program leaders managed the development of the Program in a manner consistent with emerging theories that we now associate with the field of kt. This paper describes the often unrecognized and unreported “real-world” barriers that were faced in the early years of the Program before it acquired its current international stature and credibility. Those that follow may want to anticipate similar issues.

Table iii lists key success factors for the Program. They include

strong organizational leadership, not from the Program itself, but from the parent organization Cancer Care Ontario, which provided adequate funds and supported the Program and its vision during times of criticism from influential actors within the organization.

active facilitation of cpg development by providing a methodology resource and a conceptual framework that respects the time and educational needs of participants and their need for a vision if they are to contribute constructively.

commitment to high quality in the final products to establish credibility, especially among the academic “elites.” “High quality” here refers mainly to the cpg documents themselves, which meet the principles and incorporate the rigour of an evidence-based approach to a degree beyond most other cpg documents.

responsiveness to the needs of participants (community-based and academic) and of clients (policy- and decision-makers) through innovative programming on a continuous basis as reflected by the reactive strategies used.

inclusiveness—specifically, involving all stakeholders and multiple disciplines throughout the process.

a level of transparency that fosters the trust of all participants from various sectors.

TABLE III.

Key success factors

| Organizational leadership support (loyalty and funding) |

| Facilitating participant contributions [methodology resource, conceptual framework (vision)] |

| Commitment to quality in process and products (gain in credibility) |

| Responsiveness to client and participant needs and concerns through innovative action |

| Inclusiveness (involvement of participants representing multiple disciplines and practice environments) |

| Transparency (gradual building of trust) |

These experiences are not necessarily transferrable to more widely distributed practice environments (primary care, for instance). The Program benefited from being located within a recognized and legislatively legitimized system of care. However, some of the barriers may be familiar in other environments, and the Program’s generally responsive approach may inspire others faced with similar challenges.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The support and participation of the Province of Ontario oncology community and especially panel chairs, health care organizations, Cancer Care Ontario, and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care is acknowledged. Also acknowledged are the ongoing dynamic innovations of the pebc under the leadership of Dr. Melissa Brouwers. The leadership of Dr. Mark Levine is also acknowledged in recognition of his insistence, in 1994, as a regional cancer centre director, on evidence-based guideline development, which allowed for the creation of the guideline model described.

Footnotes

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The author’s work in kt is supported by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, the Priorities in Cancer Care Network (supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research), and the Canadian Centre for Applied Research in Cancer Control (supported by the Canadian Cancer Society).

kt refers to “knowledge translation.” More recently, the term “knowledge translation and exchange” (kte) has been popularized. As used here, kt refers to both terms.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.Grunfeld E. Knowledge translation to improve cancer control in Canada: a new standing series in Current Oncology. Curr Oncol. 2011;18:9–10. doi: 10.3747/co.v18i1.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Browman GP, Levine MN, Mohide EA, et al. The practice guidelines development cycle: a conceptual tool for practice guidelines development and implementation. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:502–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.2.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine M, Browman G, Newman T, Cowan DH. The Ontario cancer treatment practice guidelines initiative. Oncology (Williston Park) 1996;10(suppl):19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgers JS, Fervers B, Haugh M, et al. International assessment of the quality of clinical practice guidelines in oncology using the Appraisal of Guidelines and Research and Evaluation Instrument. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2000–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fervers B, Remy-Stockinger M, Graham ID, et al. Guideline adaptation: an appealing alternative to de novo guideline development. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:563–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-7-200804010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fervers B, Burgers JS, Haugh MC, et al. Adaptation of clinical guidelines: literature review and proposition for a framework and procedure. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18:167–76. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Browman GP, Newman TE, Mohide EA, et al. Progress of clinical oncology guidelines development using the practice guidelines development cycle: the role of practitioner feedback. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1226–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Browman GP, Makarski J, Robinson P, Brouwers M. Practitioners as experts: the influence of practicing oncologists “in-the-field” on evidence-based guideline development. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:113–19. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ. 1995;153:1423–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt DL, Haynes RB, Hanna SE, Smith K. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 1998;80:1339–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Locock L, Dopson S, Chambers D, Gabbay J. Understanding the role of opinion leaders inn improving clinical effectiveness. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:745–57. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00387-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Greener J, et al. Is the involvement of opinion leaders in implementation of research findings a feasible strategy? Implement Sci. 2006;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, O’Brien MA, Oxman AD. Does telling people what they have been doing change what they do? A systematic review of the effects of audit and feedback. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:433–6. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.018549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitson AL, Rycroft–Malone J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the parihs framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implement Sci. 2008;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bentley C, Browman GP, Poole B. Conceptual and practical challenges for implementing the communities of practice model on a national scale—a Canadian cancer control initiative. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Browman GP. Development and aftercare of clinical guidelines: the balance between rigor and pragmatism. JAMA. 2001;286:1509–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.12.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sudsawad P. Knowledge Translation: Introduction to Models, Strategies and Measures. Madison, WI: The National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research at the Southwest Educational Development Laboratory; 2007. [Available online at: http://www.ncddr.org/kt/products/ktintro; cited October 4, 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oborn E, Barrett M, Racko C. Knowledge Translation in Healthcare: A Review of the Literature. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Judge Business School, University of Cambridge; 2010. [Available online at: http://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/research/working_papers/2010/wp1005.pdf; cited October 4, 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estabrooks CA, Thompson DS, Lovely JJ, Hofmeyer A. A guide to knowledge translation theory. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:25–36. doi: 10.1002/chp.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham ID, Tetroe J, on behalf of the KT Theories Research Group Some theoretical underpinnings of knowledge translation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:936–41. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) About Knowledge Translation [Web page] Ottawa, ON: CIHR; 2009. [Available at: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html; cited October 4, 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barwick MA, Peters J, Boydell K. Getting to uptake: do communities of practice support the implementation of evidence-based practice? J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18:16–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lomas J. Retailing research: increasing the role of evidence in clinical services for childbirth. Milbank Q. 1993;71:439–75. doi: 10.2307/3350410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindblom CE. The science of “muddling through. Public Adm Rev. 1959;19:79–88. doi: 10.2307/973677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fervers B, Hardy J, Blanc–Vincent MP, et al. sor: project methodology. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(suppl 2):8–16. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Browman G. Background to clinical guidelines in cancer: sor, a programmatic approach to guideline development and aftercare. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(suppl 2):1–3. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Constantinides P, Barrett M. Large-scale ict innovation, power, and organizational change: the case of a regional health information network. J Appl Behav Sci. 2006;42:76–90. doi: 10.1177/0021886305284291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Star SL, Griesemer J. Institutional ecology, “translations,” and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907–1939. Soc Stud Sci. 1989;19:387–420. doi: 10.1177/030631289019003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cancer Care Ontario (CCO) Treating Non-Small Cell (nsc) Lung Cancer According to Guidelines [Web page] Toronto, ON: CCO; 2010. [Available at: http://www.csqi.on.ca/cms/one.aspx?portalId=63405&pageId=67863; cited October 4, 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wirtzfeld DA, Mikula L, Gryfe R, et al. Concordance with clinical practice guidelines for adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage i–iii colon cancer: experience in 2 Canadian provinces. Can J Surg. 2009;52:92–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Major P, Petrella TM, Brouwers MC, Johnston ME, Lockman S, Browman GP. Concordance between practice guidelines on adjuvant therapy for colon cancer and clinical practice at a regional cancer centre [abstract 1040] J Clin Oncol. 2002;21 [Available online at: http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=16&abstractID=1040; cited December 14, 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biagi JJ, Wong R, Brierley J, Rahal R, Ros J. Assessing compliance with practice treatment guidelines by treatment centres and the reasons for non-compliance [abstract e17507] J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342:1317–22. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92244-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grimshaw J, Russell IT. Achieving health gain through clinical guidelines ii: ensuring guidelines change medical practice. Qual Health Care. 1994;3:45–52. doi: 10.1136/qshc.3.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Westert GP. Effects of evidence-based practice guidelines on quality of care: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:385–92. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.028043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]