Abstract

Purpose

There is an increased incidence of maxillofacial trauma all over the world. A study was conducted to find out the epidemiological characteristics of maxillofacial trauma in Northern districts of Kerala.

Methods

All the trauma patients who attended the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Government Dental College, Calicut, Kerala during the period of 2006–2007 was included in the study. The incidence, prevalence, age and sex distribution, seasonal and daily variations and aetiology of maxillofacial trauma were studied. The pattern and demographic distribution of fractures of maxillofacial skeleton also were studied.

Results

This study indicates a significant increase in the incidence of maxillofacial trauma in the region. There was a male predominance and the highest incidence was in the age group of 20–40 years. Road traffic accident was the most common aetiological factor causing maxillofacial trauma. More than 30% of trauma cases suffered fracture of maxillofacial skeleton. There was an increased incidence of midface fracture when compared to mandibular fractures in the study. Most common site of mandibular fracture was in the parasymphysis region and in the midface was the zygomatic complex region.

Conclusion

The increased incidence of maxillofacial trauma following road traffic accidents noted in this study reveals the need for formulating preventive measures in the state of Kerala. Increasing facilities for the management of maxillofacial trauma at local hospitals and medical colleges is mandatory. Training of the paramedical personnel, health workers and also the public regarding first aid and primary trauma care is also necessary.

Keywords: Maxillofacial trauma-Northern Kerala-Epidemiology, Mandibular fractures, Midface fractures

Introduction

Injuries to the face were common since time immemorial. Surveys of facial injuries have shown that the aetiology varies from one country to another and even within the same country depending on the prevailing socioeconomic, cultural and environmental factors [9]. Epidemiological studies of maxillofacial trauma is lacking from the Malabar region of Kerala. Facial trauma is an important health issue because its incidence has repeatedly been shown to be associated with motor vehicle accident and assaults [3], both of which can be prevented. A clearer understanding of the demographic patterns of maxillofacial injuries will assist health care providers as they plan and manage the treatment of traumatic maxillofacial injuries. Such epidemiological information can also be used to guide the future funding of public health programs geared towards prevention.

Studies from most developing countries of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, however, have shown that road traffic accidents are the predominant cause of maxillofacial trauma [2, 15, 17]. Less common causes of facial injuries are fall, industrial accidents and sports. In the more economically advanced countries of Western Europe [20] Australia [23] and United States of America [19] maxillofacial injuries are more often caused by interpersonal violence in the form of assaults and gunshot injuries.

No studies have been done so far to find out the aetiological factors and to estimate the extent of various maxillofacial trauma patterns in the northern districts of Kerala state. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department of Government Dental College, Calicut is the major maxillofacial trauma centre for the five northern districts viz. Wayand, Kozhikode, Kannur, Malappuram, Thrissur and Palakkad. The profile of the maxillofacial trauma in these districts is studied by analyzing the trauma patients reporting to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Casualty of Government Dental College, Calicut. So a prospective study was conducted for a period of 1 year starting from 1 June 2005 to assess the epidemiological characteristics of various maxillofacial trauma patterns.

Aims and Objectives

The following parameters were taken into account

Age and sex distribution of maxillofacial trauma.

Aetiological factors causing maxillofacial trauma.

Incidence of maxillofacial trauma due to road traffic accidents on different roads; viz. national highway, state highway, rural and city roads.

Pattern and demographic distribution of fractures at different sites of the maxillofacial skeleton.

Seasonal and daily variation in the incidence of maxillofacial trauma.

Materials and Methods

Various maxillofacial trauma patterns in the patients who attended the casualty of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department of Government Dental College, Calicut from 1st June 2005 to 31st May 2006 were included in the study. Patients with fatal injuries were excluded from this study. A proforma was prepared. The personal data, detailed description of the incidence, clinical signs and symptoms of the patients were recorded. Detailed clinical examination was done and soft tissue lacerations, tooth injuries, number and site(s) of fracture(s) of maxillofacial skeleton etc. were recorded. The diagnosis was based on clinical and radiological findings. In relevant cases CT scan was also done. The data obtained were computerized and analyzed using Statistica software.

The aetiological factors were divided into road traffic accidents, falls, interpersonal violence, sports, occupational hazards and miscellaneous (van Beek and Merkx [25]). The road traffic accidents were analyzed regarding the type of vehicle [light motor vehicle, bicycle (pedalled), motorcycle, heavy motor vehicle and pedestrians] and road types (national highway, state highway, city road and rural road).

Mandible fractures were recorded as dentoalveolar, condylar, ramus, angle, body, symphyseal and parasymphyseal regions [21] and middle-third of the face as dentoalveolar, Le Fort I, II, and III types, zygomatic, nasal, orbital, palatine and sinus.

Results

Incidence, Age and Sex

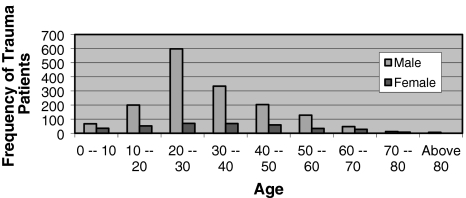

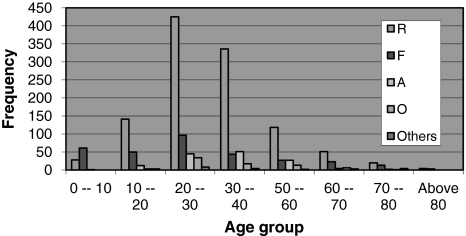

During the study period a total number 1950 cases of maxillofacial trauma reported to the casualty department of OMFS in which 1596 were male and 354 were female. (male:female = 4.1:1).

Patients’ age ranged from 1 year to 89 years (mean 33). The highest numbers of patients were in the 20–30 years age group (No: 668, 34.26%). The age of male patients ranged from 1-year male to 89 years (mean 32.55 years). The age of female patients were from 2 to 79 years (mean age 35 years). The peak age groups among male patients were 20–30 (37.56%); and that for females were also 20–30 (19.77%). Only six cases were reported above 80 years of age (0.38%). Below 10 years there were 65 cases (4.08%).

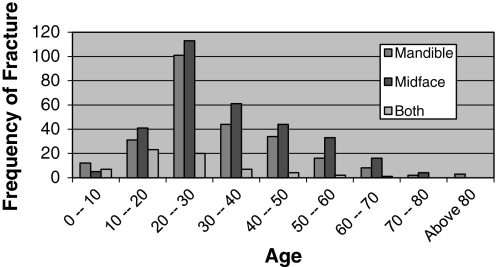

There was an overwhelming male preponderance in all age groups. The overall male–female ratio was 4.1:1. The age and sex-wise distribution of trauma cases is as shown in the Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Age and sex wise frequency distribution of trauma patients

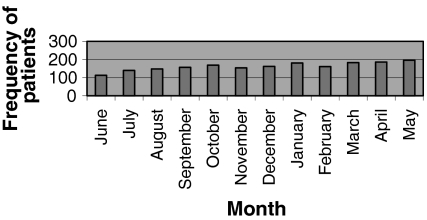

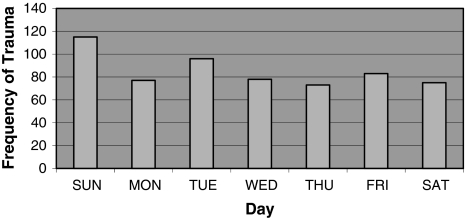

Maxillofacial trauma was highest in the months of April (186) and May (196). The monthly distribution of trauma cases is as shown in the Fig. 2. A higher incidence of trauma was noticed on Sundays, which was statistically significant. The day-wise distribution of trauma cases is as shown in the Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Monthly distribution of trauma cases

Fig. 3.

Day-wise distribution of trauma

Since chi-square value is higher than the table values the frequency difference over the months is statistically significant.

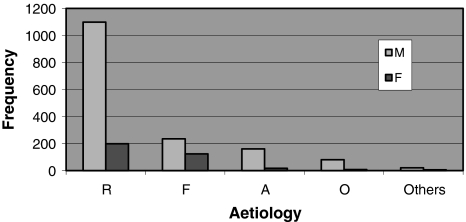

Aetiology

Most of the trauma cases were due to road traffic accidents (1297, 66.46%). The next cause was fall 359 (18.41%). The remainder was caused by violence (178, 9.12%), occupational accidents (89, 4.56%), sports (27, 1.38) and others (27, 1.38%). The aetiological distribution of maxillofacial trauma cases is as in the Figs. 4 (sex-wise) and 5 (age-wise).

Fig. 4.

Aetiology—sex-wise

Fig. 5.

Aetiology vs. age group

Road Traffic Accidents

Total number of RTA cases were 1297 (66.46%) of which 449(34.61) had fractures of maxillofacial skeleton. Male female ratio of RTA cases was 5.5:1.

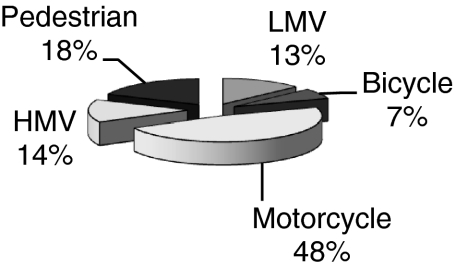

In the road traffic accidents the motorcycle was the vehicle involved in majority of cases (618, 47.5%) followed by heavy motor vehicle 186 (14.4%). Pedestrian trauma in 238 cases (18.4%). This was almost always involving a vehicle. The vehicle-wise distribution of road traffic accidents cases is as in the Figs. 6 and 7.

Fig. 6.

Type of vehicle

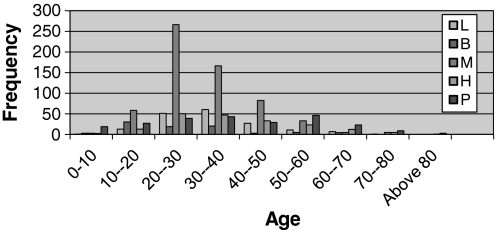

Fig. 7.

Age vs. type of vehicle

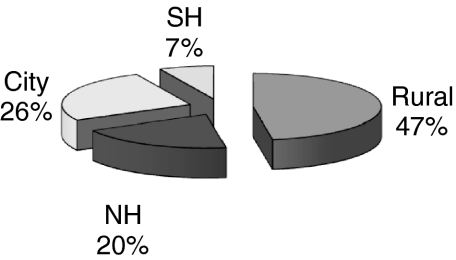

The highest number of road traffic accidents occurred on the rural roads 617(47.6%). Next prominent location was city roads 337, 26% and the rest in the national highways (254, 19.6%) and state highways (89, 6.8%). The road location-wise distribution of road traffic accidents cases is as in the Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Distribution of types of roads

Fall

Second aetiological factor of maxillofacial trauma was fall. 359 (18.41%) of the trauma cases were due to fall. The most commonly affected age group in this category was the 20–30 years (96, 26.74%). 17% (61) of the fall were in the 0–10 year age group.

Violence

The number of assault cases was 178 (9.13%). The male- female ratio was 9.5:1. The assault was mainly due to interpersonal rivalry. Some mob violence was also reported (20 cases, 11.23%). No trauma due to religious or racial violence was reported during this period.

Other Causes

Sports related injuries and occupational hazards were very few and constituted 27 (1.38%) and 89 (4.56%) respectively.

Other rare causes for the maxillofacial trauma in this study include fall from train, fall due to electric shock, acid burn, and injury due to fishbone and cheek bite. There was one gunshot injury by an air gun. It was an accident while cleaning the gun.

Influence of Alcohol

Of the total number of 1950 trauma cases 675 cases (34.61%) were under the influence of alcohol during the incident. 450 (34.7%) of RTA cases and 138 (77.5%) of assault cases were reported to have consumed alcohol before the incident. During the beginning of the study enquiries about the use of helmet and seat belt were made, but as only very few were using this that question was dropped from the questionnaire.

Fracture Patterns

During the study out of the 1950 trauma cases 627 (32.2%) had fractures of maxillofacial skeleton. In this 543 were male and 84 were female.

The male female ratio was 6.5:1. The highest incidence of maxillofacial fracture was in the age group of 20–30 years (37.6%). The age distribution of the fracture cases is as shown in the Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Age-wise distribution of types of fractures

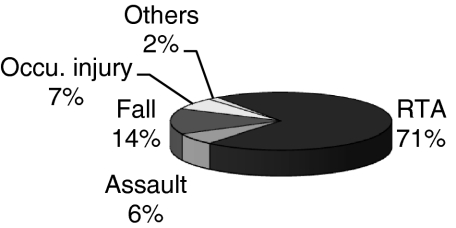

The major causative factor of maxillofacial fracture was road traffic accidents (444 cases, 70%) followed by fall (91 cases, 15%). Etiological factors causing maxillofacial fractures are as shown in the Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Aetiology of maxillofacial fracture

251 cases were having only fractures of mandible and 317 cases were having only fractures of midface. Fractures of both mandible and midface occurred in 64 cases. In the 632 cases there were 1237 (mandible 663, midface 574) fracture lines at different sites (1.95 fracture/case).

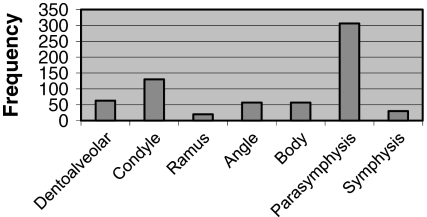

Mandible Fractures

Site-wise distribution of the mandible fracture cases is given in the Fig. 11. In the 251 cases of mandible fractures there were 663 fractures at different sites. The most prominent site of mandibular fracture was parasymphysis (306, 46.15%). Distribution of mandible fractures in the other sites were dentoalveolar (63, 9.5%), condyle (130, 19.6%), ramus (20, 3.01), angle (57, 8.61), body (57, 8.61) and symphysis (30, 4.52%) (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Site-wise distribution of mandible fractures

Of the total number of 632 fracture cases, 403(64.27%) had single fractures, 136 (21.69%) had two fractures and 88(14.04%) had fractures at more than two sites. In 108 (17.1%) cases there were bilateral fractures. The most common combination of mandibular fractures was subcondylar and parasymphysis fracture (21 cases), followed by bilateral parasymphysis fractures (15 cases), angle and parasymphysis (12 case) and bilateral subcondylar (10 cases).

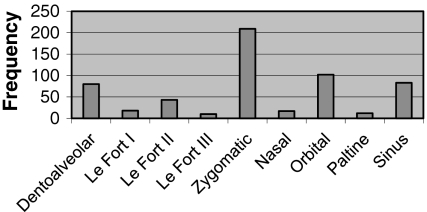

Mid Face Fractures

Site-wise distribution of the midface fracture cases is given in the Fig. 12. Midface fracture occurred in 381 cases out of the 632 cases. 64 had midface fracture along with mandible fractures. In 381 midface fracture cases there were 574 fracture lines. The most prevalent type of midface fracture was in the zygomatic region (209, 36.4%), followed by orbital (102, 17.8%), Le Fort I (18, 3.1%), Le Fort II (43, 7.5%), Le Fort III (10, 1.7%).

Fig. 12.

Frequency of different type of midface fractuers

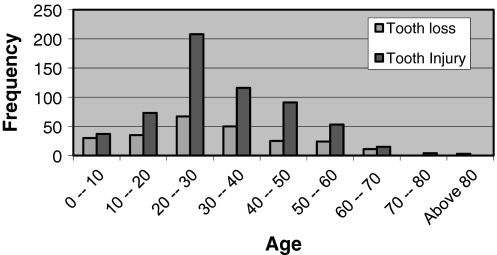

Tooth Injury

Of the total number of 1950 trauma cases the tooth was injured in 842 (43.18%) cases of which 245 (29.1%) had lost one or more teeth and 597(70.9%) had restorable injury (tooth fractures, mobility, displacements etc.) (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13.

Age-wise distribution of tooth injury

Discussion

Incidence

The incidence of maxillofacial trauma in the present study was 1950. Number of cases with one or more maxillofacial fractures is 627(32.15%). In comparison with a similar study conducted in Trivandrum by Nair and Paul [17], there were more than double the number of fracture cases. Other studies also show an increase in the maxillofacial trauma Kontio [16] reported 27% of increase in the maxillofacial trauma by 16 years from 1981 to 1997. Fasola [10] reported an increase in maxillofacial trauma. Buchanan [5] reported that maxillofacial trauma almost doubled in a period of 12 years.

In India the recent hike in socio-economic status has directly affected the incidence of facial fractures. There is a fast growth in the volume of road traffic. A substantial rural to urban drift of the productive segment of the population has increased the density of urban population. Deteriorating infrastructure such as bad roads, driving under the influence of alcohol 4, and non-compliance with seat belt [27] and crash helmet legislation [6] also can be considered as the factors contributing to the increasing road traffic accidents in developing countries.

Age & Sex Distribution

Age of the patients suffering from maxillofacial trauma ranged from 1 year to 89 years with highest incidence of fracture in the 20–30 year age group followed by 30-40 year age group both in males and females which correlated with reports of other investigators [7, 8, 18, 24].

There was a clear male preponderance with male female ratio being 4.1:1. The sex ratio in other published series ranges from 2.8:1 [8] to 11:1 [2]. In most of the studies it was around 3:1. However Adekeye [3] reported a male female ratio of 16.9:1.

Seasonal and Daily Variation

A significantly higher incidence of maxillofacial trauma was noticed on Sundays. Fasola [11] and Chrcanovic [7] report an increased incidence of road traffic accidents in weekends. Kontio [16] also reports a similar increased incidence of maxillofacial trauma at the weekends.

The number of maxillofacial trauma cases were significantly high in the months of April and May in the present study. Ogundare [19] reports an increased violence in summer. Kontio [16] in his study found an increase in incidents in June and August. The increased incidence in the weekends and in the months of summer holidays indicates an increased incidence of maxillofacial trauma during increased leisure time.

Aetiology of Fractures

The main causes of maxillofacial fractures in all the studies are road traffic accidents, falls, violence and sports related injuries. In the present study road traffic accident was the most frequent cause (444, 70%) of facial trauma, followed by fall (91, 15%). In the studies of Adekeye [3], Nair [17], Tan [24], Hussain [12], Oikarinen [20], Adebayo [2] also gives the same sequence.

Studies from most of the developed countries inter personal violence has become the major cause of maxillofacial trauma. Ogundare [19], Schon [23], Buchanan [5]. In developing countries road traffic accidents continues to be the prime aetiological factor of maxillofacial trauma. Iida [13], Wong [26]. This is in accordance with our present study.

Type of Vehicle

In road traffic accidents cases, an analysis was done to find out the prevalence of different types of vehicles involved. Motorcycle was the most prominent group (618, 47.5%). In studies of Oginni [18], Chapman [6] also similar results were obtained.

Roads

The prevalence of road traffic accidents in different types of roads was studied. Road traffic accidents were significantly higher in number on rural roads 617(47.6%). Next prominent location was city roads 337 (26%). Lesser number of cases were reported on the national highways (254, 19.6%) and in state highways (89, 6.8%). The increased incidence of road traffic accidents in rural and city roads may be due to increased number of curvatures in the hilly terrain of Malabar.

Influence of Alcohol

Of the total number of 1950 trauma cases, 655(34.61%) reported to have consumed alcohol before the incident. 34% of RTA cases and 77.5% of assault cases had abused alcohol. Atanosov [4], Adams [1], Buchanan [5] also found significant relationship between alcohol abuse and maxillofacial trauma.

Fracture Patterns

In the present study there were 632 cases with fractures in which there were 1237 (mandible 663, midface 574) fracture lines at different sites (1.95 fracture/case).

Cases with midface fracture were more than the mandible fracture. This was in contrast with the results obtained by Nair and Paul [17] in which number of mandible fractures was almost double that of midface fractures.

In our study the most common site of fracture was parasymphysis (306, 24.73%) followed by zygomatic (209, 16.9%). King [14] in a study found a statistically significant association between road traffic accidents and parasymphysis fractures whereas in assault cases there were more angle fractures. In their study children and young adults seems to suffer more parasymphysis fractures. Ogundare [19] also reported assault as the major cause and angle as the most prevalent site of fracture. Atanasov [4], Wong [26] reported that motorcycle accidents (79.5%) were the major cause for fractures of mandible and the parasymphysis was the most common fracture site.

Distribution of Mandible Fractures

In the present study the most common site of mandibular fracture was parasymphysis (306, 46.15%) followed by condyle (130, 19.61%). Adekeye [3] Nair [17] and Adebayo [2] reported the body as the most prominent site. van Beek [25] found condyle as the most common site.

Of the total number of 632 fracture cases, 403(64.27%) had single fractures, 136 (21.69%) had two fractures and 88(14.04%) had fractures at multiple sites. In 108 (17.1%) cases there were bilateral fractures. The most common combination of mandible fractures was subcondylar and parasymphysis (21 cases), followed by bilateral parasymphysis (15 cases), angle and parasymphysis (12 case) and bilateral subcondylar (10 cases).

Distribution of Midface Fractures

The most common type midface fracture in this study was fracture of zygomatic complex. In most of the reports (Adekeye [3], Nair [17], Adebayo [2], Peter Banks [22]) the zygomatic complex fracture was the most common type of midface fracture.

Limitations of the Study

We had assessed only few parameters pertaining to maxillofacial injuries. We had included in our study only those patients who reported to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Casualty. Those patients who were fatally injured did not figure in our study. Isolated nasal fractures might have gone to ENT Casualty, which resulted in its reduced incidence. Mortality in different roads were not assessed which may be a factor in decreased number of maxillofacial trauma in National Highway and Sate Highway seen in our study.

Conclusion

The increased incidence of maxillofacial trauma following road traffic accidents noted in this study reveals the need for formulating preventive measures in the state of Kerala. Prohibition of driving under influence of alcohol, over speeding, proper repair and maintenance of roads, introduction of seat belts and helmet legislation are absolutely necessary. Detailed education of the driving license holders and pedestrians about the traffic rules and regulations is essential. Increasing facilities for the management of maxillofacial trauma at local hospitals and medical colleges is mandatory. Training of the paramedical personnel, health workers and also the public regarding first aid and primary trauma care is also necessary.

One of the points noted in the present study is the increased number of trauma victims in the age group of 20–30 years. Thus people in the prime of their life are affected and it is a huge loss to the society and country. This underlies the need to incorporate traffic rules in the school curriculum.

Another point in question is the influence of alcohol in trauma victims. 34.61% of the patients have consumed alcohol prior to the accident. Among the cases involved in interpersonal violence 77% gave a history of alcohol consumption prior to the incident. It is for the society to ponder and steps taken to reduce or eradicate this social evil.

Rural roads causing a larger number of trauma cases may be a clear indication of the unscientific surveying and construction techniques used. So the authorities need to look into planning of the roads, reduce curves, put speed breakers etc.

As a whole we had tried to assess only certain parameters of maxillofacial trauma. The social and economic implications of trauma were not in the scope of this study. We suggest more detailed studies to recognize the changing trends of maxillofacial injuries, to assess the effects of maxillofacial injuries, to assess the effectiveness of management and to assess the effectiveness of public education.

In 2007 as per Kerala High Court order Helmets were made compulsory for two wheeler riders. The effect of the Helmet rule on maxillofacial injuries was also studied prospectively in our institution.

Contributor Information

V. Ravindran, Phone: +495-2356193, Email: ravi_nambisan@yahoo.co.in

K. S. Ravindran Nair, Phone: +9349982045, Email: ksravinair@gmail.com

References

- 1.Adams CD, Januszkiewcz JS, Judson J. Changing patterns of severe craniomaxillofacial trauma in Auckland over eight years. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70(6):401–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.2000.01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adebayo ET, Ajike OS, Adekeye EO. Analysis of the pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Kaduna, Nigeria. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41(6):396–400. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(03)00165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adekeye EO. The pattern of fractures of the facial skeleton in Kaduna, Nigeria. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;49:491–495. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atanasov DT. A retrospective study of 3326 mandibular fractures in 2252 patients. Folia Med Plovdiv. 2003;45(2):38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchanan J, Colquhoun A, Friedlander L, Evans S, Whitley B, Thomson M. Maxillofacial fractures at Waikato Hospital, New Zealand: 1989 to 2000. N Z Med J. 2005;118(1217):U1529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman HR, Curran AL. Bicycle helmets—does the dental profession have a role in promoting their use? Br Dent J. 2004;196(9):555–560. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chrcanovic BR, Freire-Maia B, Souza LN, Araujo VO, Abreu MH. Facial fractures: a 1-year retrospective study in a hospital in Belo Horizonte. Pesqui Odontol Bras. 2004;18(4):322–328. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242004000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deogratius BK, Isaac MM, Farrid S. Epidemiology and management of maxillofacial fractures treated at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 1998–2003. Int Dent J. 2006;56(3):131–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2006.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis E, Moos KF, El-Attar A. Ten years of mandibular fractures. An analysis of 2137 cases. Oral Surg. 1985;59:120–129. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fasola AO, Nyako EA, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Trends in the characteristics of maxillofacial fractures in Nigeria. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(10):1140–1143. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fasola AO, Lawoyin JO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Inner city maxillofacial fractures due to road traffic accidents. Dent Traumatol. 2003;19(1):2–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2003.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussain SS, Ahmad M, Khan MI, Anwar M, Amin M, Ajmal S, Tariq F, Ahmad N, Iqbal T, Malik SA. Maxillofacial trauma: current practice in management at Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2003;15(2):8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iida S, Kogo M, Sugiura T, Mima T, Matsuya T. Retrospective analysis of 1502 patients with facial fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30(4):286–290. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King RE, Scianna JM, Petruzzelli GJ. Mandible fracture patterns: a suburban trauma center experience. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25(5):301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klenk G, Kovacs A. Etiology and patterns of facial fractures in the United Arab Emirates. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14(1):78–84. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200301000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kontio R, Suuronen R, Ponkkonen H, Lindqvist C, Laine P. Have the causes of maxillofacial fractures changed over the last 16 years in Finland? An epidemiological study of 725 fractures. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21(1):14–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2004.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nair BK, Paul G. Incidence and aetiology of maxillofacial skeleton in Trivandrum—a retrospective study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:40–43. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oginni FO, Ugboko VI, Ogundipe O, Adegbehingbe BO. Motorcycle-related maxillofacial injuries among Nigerian intracity road users. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(1):56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogundare BO, Bonnick A, Bayley N. Pattern of mandibular fractures in an urban major trauma center. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(6):713–718. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oikarinen KI, Schutz P, Thalib L, Sandor GK, Clokie C, Meisami T, Safar S, Moilanen M, Belal M. Differences in the etiology of mandibular fractures in Kuwait, Canada, and Finland. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20(5):241–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2004.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peter Banks (1993) Killy’s fractures of the mandible, 4th edn. Varghese Publishing House, Bombay, pp 1–10

- 22.Peter Banks (1992) Killy’s fractures of the middle third of the facial skeleton, 5th edn. Varghese Publishing House, Bombay, pp 11–16

- 23.Schön R, Roveda SIL, Carter B (2001) Mandibular fractures in Townsville, Australia: incidence, aetiology and treatment using the 2.0 AO/ASIF miniplate system. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 39:145–148 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Tan WK, Lim TC. Aetiology and distribution of mandibular fractures in the National University Hospital, Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1999;28(5):625–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beek GJ, Merkx CA. Changes in the pattern of fractures of the maxillofacial skeleton. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28(6):424–428. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0020.1999.280605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong KH. Mandible fractures: a 3-year retrospective study of cases seen in an oral surgical unit in Singapore. Singapore Dent J. 2000;23(1 Suppl):6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood EB, Freer TJ. Incidence and aetiology of facial injuries resulting from motor vehicle accidents in Queensland for a three-year period. Aust Dent J. 2001;46(4):284–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2001.tb00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]