Abstract

In primates the retina receives input from histaminergic neurons in the posterior hypothalamus that are active during the day. In order to understand how this input contributes to information processing in Old World monkey retinas, we have been localizing histamine receptors (HR) and studying the effects of histamine on the neurons that express them. Previously, we localized HR3 to the tips of ON bipolar cell dendrites and showed that histamine hyperpolarizes the cells via this receptor. We raised antisera against synthetic peptides corresponding to an extracellular domain of HR1 between the 4th and 5th transmembrane domains and to an intracellular domain near the carboxyl terminus of HR2. Using these, we localized HR1 to horizontal cells and a small number of amacrine cells and localized HR2 to puncta closely associated with synaptic ribbons inside cone pedicles. Consistent with this, HR1 mRNA was detected in horizontal cell perikarya and primary dendrites and HR2 mRNA was found in cone inner segments. We studied the effect of 5 µM exogenous histamine on primate cones in macaque retinal slices. Histamine reduced Ih at moderately hyperpolarized potentials, but not the maximal current. This would be expected to increase the operating range of cones and conserve ATP in bright, ambient light. Thus, all three major targets of histamine are in the outer plexiform layer, but the retinopetal axons containing histamine terminate in the inner plexiform layer. Taken together, the findings in these three studies suggest that histamine acts primarily via volume transmission in primate retina.

INDEXING TERMS: retinopetal, centrifugal, histamine receptor 1, histamine receptor 2, photoreceptor, primate

Retinopetal axons containing histamine were first described in guinea pigs (Airaksinen and Panula, 1988) and later in macaques (Gastinger et al., 1999). These axons emerge from the optic nerve head, run in the optic fiber layer, and descend orthogonally into the inner plexi-form layer (IPL), where they branch extensively. There are no cell bodies containing histamine in the retina, and axons containing histamine are also found among the ganglion cell axons in the optic nerve. A retrograde labeling study indicates that the perikarya that give rise to these axons are located in the tuberomamillary nucleus of the posterior hypothalamus (Labandeira-Garcia et al., 1990), the only area of the macaque brain where cell bodies containing histamine are found (Manning et al., 1996). These hypothalamic neurons containing histamine are not specialized for vision; they project diffusely throughout the central nervous system. They are components of the system that mediates arousal, firing most rapidly while the animal is awake (reviewed by Jones, 2005).

In the central nervous system, histamine acts on three types of G-protein coupled receptors: HR1, HR2, and HR3. The primary signaling pathway of HR1 is via activation of Gq/11. HR2 typically activates GS, leading to the stimulation of adenylate cyclase. Both are generally excitatory, but inhibitory effects have also been reported. HR3 activates GO or GI and typically decreases neurotransmitter release by inhibiting voltage gated calcium channels (reviewed by Haas and Panula, 2003). However, in macaque retinas stimulation of HR3 increases the delayed rectifier component of the voltage-dependent potassium conductance in ON bipolar cells, hyperpolarizing the cells by 5 mV, on average (Yu et al., 2009). In dark-adapted baboon retinas, histamine also decreases the rate of maintained firing and the amplitude of the light responses of ON ganglion cells (Akimov et al., 2010).

HR3 is the only histamine receptor that has been localized anatomically in the primate retina to date. Puncta containing immunoreactive HR3 are found in the outer plexiform layer (OPL), associated with both rods and cones. The labeled processes have been identified as ON bipolar cell dendrites, both by electron microscopic immunohistochemistry and by light microscopic double labeling with antibody to metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 (mGluR6; Gastinger et al., 2006). HR1 has been characterized in human retinal membrane preparations based on the binding of [3H] mepyramine (Sawai et al., 1988), but the neurons expressing the receptors have not been identified. HR2 has not been localized previously in primate retinas, but histamine elevates cyclic AMP in a cell line derived from human retinoblastoma (Kyritsis et al., 1984). There is indirect evidence for the presence of HR1, HR2, or both in monkey retinas based on the effects of histamine on ganglion cells. When histamine and the HR3 agonist (R)-alpha-methylhistamine are applied to monkey retinas in succession, their effects on ganglion cells are not always the same (Gastinger et al., 2004). These experiments were designed to identify the cells in macaque and baboon retinas that express HR1 and HR2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Histamine receptor 1

HR1 antibody

A synthetic peptide corresponding to the extracellular loop between the 4th and 5th transmembrane domains of human HR1 and consisting of amino acids 164–186 was made at Bachem Laboratories (Torrance, CA). The amino acid sequence was GWNHFMQQTSVRREDKCETDFYD. The following procedures were performed at Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, TX). The peptide was crosslinked to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) via the cysteine thiol group using Sulfo-SMCC. The hemocyanin-linked peptide was dialyzed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), sterile-filtered, and 100 µg was injected intramuscularly (IM) into a goat. Freund’s Complete Adjuvant was used for the initial immunization and subsequent booster immunizations used Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. Blood was tested every week to assess the need for further booster injections. Subsequent booster immunizations were given on the same day as blood was collected; this was repeated four times. Some of the immune serum was purified by affinity chromatography with the synthetic peptide coupled to sepharose. The initial concentration of IgG in the affinity purified fraction was 1 mg/ml.

HR1 fusion protein

A GST-fusion protein corresponding to amino acids 155 to 199 of a cDNA clone of human HR1 (Accession No. BC060802) was obtained from Proteintech Group (Chicago, IL). The clone was prepared at Proteintech by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of a 120-bp segment of the human HR1 cDNA using the primers containing Bam HI restriction sites at 5′-TTTTGGATC CGTTATTCCCATTCTAGGCTGG-3′ (forward) and XhoI restriction TTTTCTCGAGGTTGATGATGGCAGTCATGAC-3′ (reverse). Unique restriction sites are underlined. The cDNA was amplified using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, San Diego, CA) and cloned into the BamHI and XhoI sites of pGex4T (GE Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ). The fusion protein was expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 cells. The transformants were induced by the addition of the lactose analog IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 2 hours.

Immunoblotting

Crude lysates of induced bacterial cells expressing GST fusion protein were used for western blotting. Samples were assayed for protein content with the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Bacterial lysates were adjusted to 1.3 mg protein/ml and β-mercaptoethanol added prior to heating samples to 65°C and loading the gels. Aliquots containing 10 µg of protein were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Following transfer, membranes were blocked with 2% nonfat dry milk in high-salt TBST (500 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 0.05% Tween-20) for 5 hours at room temperature and then probed with antihistamine receptor 1 (dilution 1:2,500) goat affinity-purified antibody for 2 days at 4°C. To confirm the presence of GST fusion proteins in the sample, membranes were probed with anti-GST (dilution 1:1,000) mouse monoclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Signals were developed with either Cy5-conjugated donkey antigoat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) or peroxidase-conjugated donkey antimouse secondary antibodies (Pierce) diluted 1:5,000 in 1× TBST with 2% nonfat dry milk (O’Brien et al.,2006). The membranes were then washed and imaged with a Typhoon 9400 imager (GE Healthcare Biosciences) or detected by chemiluminescence using x-ray film (Supersignal; Pierce). Western blot analysis showed that a 34-kDa band was detectable, corresponding to the expected size of GST-HR1 fusion protein (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

HR1 and HR2 antibodies. Immunoblotting analysis of induced bacterial cells expressing GST fusion protein and antibody selectivity in transfected HeLa cells. Nitrocellulose membranes were probed with affinity-purified anti-HR1 antisera (A) and G-purified anti-HR2 (B). Bands corresponding to the expected sizes of both GST-HR1 and GST-HR2 fusion proteins were detected by chemiluminescence using x-ray film. HeLa cells were transfected with HR1 (C,E) or HR2 (D,F) cDNAs. C: HR1 immunoreactivity (red) in HR1 transfected cells (control) was localized to the cytoplasm in granular aggregate form. D: HR1 immunolabeling was absent in cells transfected with HR2 cDNA. E: HR2 immunolabeling was absent in cells transfected with HR1 cDNA. F: HR2 immunoreactivity (red) in HR2 transfected cells (control) was localized to the cytoplasm in granular aggregate form. DAPI staining (blue) indicated that labeling was confined around the nucleus. Scale bars = 20 micrometers. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Cell line expressing HR1

The full coding sequence of human HR1 (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL) was subcloned into pcDNA 3.1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). HeLa cells (clone CCL2; ATCC) were grown with minimum essential media (MEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 24 hours with 5% CO2 at 37°C. After reaching 80–100% confluency, confluent cells were plated on coverslips, transfected with 2 µg of plasmid using GenePorter 2 (Genlantis, San Diego, CA), and grown in serum-free medium for 4 hours. Transfected cells were grown for 24 hours with medium containing 10% FBS. After rinsing the cells twice with fresh MEM containing 10% FBS, cells were allowed to stabilize for a minimum of 2 hours before fixation. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, labeled with antibodies against HR1 (1:2,000), HR2 (1:2,000), and Cy3-conjugated donkey antigoat IgG (1:1,000 Jackson ImmunoResearch). Cells were coverslipped in Vectashield mounting medium containing 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole dihtydrochloride (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). HR1 immunolabeling was not detected in the untransfected HeLa cells. Immunolabeling was granular and found around the nuclei labeled with DAPI (Fig. 2C). To eliminate the possibility of crossreactivity with HR2, HR1 antibody was also tested in transfected cells that express HR2; no immunolabeling was observed (Fig. 2D).

Immunolabeling with HR1 antibody

A total of 21 pairs of macaque eyes, including tissue from 12 Macaca mulatta and 9 Macaca fascicularis, were purchased from Charles River (Houston, TX). These animals were sedated with ketamine (15 mg/kg), exsanguinated via the femoral vein, and killed with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) mixed with sodium phenytoin (50 mg/kg), following protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conforming to National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines. The eyes were removed and hemisected; the vitreous humor was removed using fine forceps within 10 minutes postmortem. Eyecups were transported to the laboratory in carboxygenated Ames medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at ambient temperature. Approximately 25 mm2 pieces of the eyecups were cut from mid-periphery or central retina and immersion fixed in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4, containing 2% or 4% paraformaldehyde for varying lengths of time. The best labeling was obtained when the tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. The fixed retinas were isolated from the retinal pigment epithelium. To facilitate penetration of the antibodies, the tissue was treated with an ascending and descending series of graded ethanol solutions in PBS (10 minutes each 10%, 25%, 40%, 25%, and 10%), or else 0.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) was included in the primary antiserum. Retinal pieces were embedded in 4% low-melting temperature agarose (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in PBS with 0.3% sodium azide (PBSa), and 50–100 µm vertical vibratome (Leica VT1000 S, Bannockburn, IL) sections were cut.

The tissue was rinsed three times in PBS after this and all other steps. It was incubated in primary antiserum or purified IgG at 4°C with 1:100 donkey serum in PBSa; in some experiments 5% Chemiblock (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was substituted for the donkey serum. In those experiments in which ethanol solutions were used to pretreat the tissue, 0.01% NP40 (Sigma-Aldrich) was included with the diluted primary antisera. Sections were incubated for a minimum of 7 days. In addition to goat antibodies against HR1 (1:1,000), vibratome sections were double-labeled using mouse monoclonal antibodies against parvalbumin (1:2,000, Swant, Bellinzona, Switzerland) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH16 1:5,000, Sigma), or else rabbit polyclonal antibody against calretinin (1:1,000, Millipore). Additional information about the antibodies is given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Antibodies Used in This Study

| Antibody | Host | Antigen | Source | Catalog No. | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR1 | Gt | 4th and 5th transmembrane domain of human HR1 (aa164–186) coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) | Bachem Laboratories, Torrance, California | N/A | 1:1,000 |

| HR2 | Gt | C-terminus of human HR2 (aa 306–327) coupled to KLH | Bachem Laboratories, Torrance, California | N/A | 1:2,000–1:5,000 |

| Parvalbumin | Ms | Parvalbumin purified from carp muscles | Swant, Bellinzona, Switzerland | PV235 | 1:2000 |

| TH16 | Ms | Rat tyrosine hydroxylase | Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO | T2928 | 1:5,000 |

| Calretinin | Rb | Guinea pig calretinin | Millipore Corporation. Temecula, CA | AB5054 | 1:1,000 |

| Arrestin | Ms | Whole native human cone arrestin clone 7G6 | Dr Peter MacLeish; Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA | N/A | 1:1,000 |

| PNA | N/A | Lectin peanut agglutinin from Arachis hypogaea Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate | Molecular Probes, Inc Eugene, OR | L-21409 | 1:1,000 |

| Ribeye | Rb | Purified glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein containing B domain {aa 563–988) of rat ribeye (U2656) | Dr. Thomas Südhof; Stanford University School of Medicine, CA | N/A | 1:500 |

| mGluR6 | Rb | C-terminal peptide (KATSTVAAPPKGEDAEAHK) of human mGluR6 | Dr. Noga Vardi; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | N/A | 1:500 |

| GluR4 | Rb | C-terminus of rat GluR4 (RQSSGLAVIASDLP) | Millipore Corporation., Temecula,CA | AB1508 | 1:500 |

| Syntaxin 3 | Rb | N-terminal peptide (KDRLEQLKAKQLTQDDC) of mouse syntaxin 3 | Dr. Roger Janz; University of Texas, Medical School, Houston | N/A | 1:500 |

Secondary antibodies were all raised in donkeys and affinity-purified. These included: antigoat IgG conjugated to Cy3 (1:1,000 Jackson ImmunoResearch), antirabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 488 (1:750; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and antimouse IgG conjugated to Cy5 (1:1000 Jackson ImmunoResearch). Sections were incubated in secondary antibodies for 2 hours at 20°C, and pieces of retina were left in secondary antibodies for 2 days at 4°C. Tissue was coverslipped in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories) with DAPI.

HR1 peptide control experiments

The synthetic peptide used for immunization and affinity chromatography was also used in blocking control experiments. Retinas were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M PB pH 7.4 overnight at 4°C. The tissue was processed with graded ethanol solutions to enhance the permeation of the antibodies and cut into 50-µm vibratome sections. The final concentration of IgG against HR1 was 0.1 mg/ml. In the control experiments, the primary antibodies were preincubated with the synthetic peptide (10 µg/µl) in 1% donkey serum and 0.01% NP-40 diluted in 0.1M PBSa. The peptide solution was centrifuged and filtered through 0.2-µm polysulfone membrane (Sigma-Aldrich). Sections were incubated for 7 days at 4°C. Preincubation with the peptide alone blocked the labeling in the retina. Tissue incubated in parallel with untreated antibody yielded positive immunolabeling.

Confocal microscopy

Images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM 510 META laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Fluorescent beads (TetraSpeck; Invitrogen) were used as reference standards to verify the colocalization of probes emitting different wavelengths of light in the same optical plane. All sections were imaged with dye-appropriate filters (330 nm excitation, 440–460 nm emission for DAPI; 540 nm excitation, 590–620 nm emission for Cyanine 3; 470 nm excitation, 530–550 nm emission for Alexa 488; 633 nm excitation, long-pass 650 nm emission for Cyanine 5). Images were acquired with a 63× oil-immersion objective as a series of optical sections ranging between 0.25 to 0.5 µm in step size. Each marker was assigned a pseudocolor and the images were analyzed as single optical sections and as stacks of optical sections projected along the y or z axis. All images were processed in Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems 9.0, San Jose, CA) to enhance brightness and contrast.

Histamine receptor 2

HR2 antibody

A synthetic peptide corresponding to a sequence near the C-terminal intracellular tail of HR2, consisting of amino acids 306–327, was made at Bachem Laboratories. The amino acid sequence was RLANRNSHKTSLRSNASQLSRT. The peptide was conjugated to KLH via glutaraldehyde for 1 hour at room temperature in PBS. This resulted in crosslinking via the amino group of the lysyl residue at position 315 in the HR2 sequence or else the amino terminus of the peptide. The hemocyanin-linked peptide was dialyzed in PBS and sterile-filtered. At Bethyl Laboratories, a goat was immunized, and serum was collected as described for HR1. A protein G chromatography method was used to purify immunoglobulins at Affinity Life Sciences (Milford, NH). The initial concentration of IgG in the purified preparations was 1 mg/ml.

HR2 fusion protein

A cDNA clone of human HR2 (GenBank: BC054510) in pCMV-SPORT6 was obtained from Open Biosystems. Specific primers were designed to amplify the cDNA region for human HR2 corresponding to amino acids 291 to 397 of the C-terminal tail. The C-terminus starts at position 290, therefore the GST fusion protein contains almost the entire C-terminal tail of the HR2, and primers for PCR were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) The primers containing Xba/Xho I restriction sites were CCTGAACCCA TTCTAGATGCTGCGCTGAAC (forward primer) and AATCTCATTTCTCGAGCCCCAGTATTCATCATAATTCC (reverse primer). Unique restriction sites are underlined. The cDNA was amplified using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase. PCR amplification of HR2-derived cDNA was achieved with the following protocol: denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, then for 30 cycles under denaturing at 94°C for 15 seconds, annealing at 58°C for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for 1 minute 15 seconds, and final extension at 72°C for 2 minutes after the last cycle. A single band corresponding to the predicted size of the amplified fragment (397 bp) was detected by agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR products were subcloned into pGEX2T (GE Life Sciences). Escherichia coli strain BL21 cells were transformed with the recombinant vector. The transformants were induced by the addition of IPTG for 2 hours.

Immunoblotting

The specificity of the HR2 antibody was tested by western blot against the HR2 C-terminal domain GST fusion protein. Detection methods similar to those used for HR1 were used for HR2. A 41-kDa band was detectable, corresponding to the expected size of GST-HR2 fusion protein (Fig. 2B).

Cell line expressing HR2

The full coding sequence of human HR2 in pCMVSPORT6 vector was transformed into HeLa cells. HeLa transfection procedures were the same as with HR1. HR2 Immunolabeling had a distribution very similar to that of HR1. That is, the labeling was granular and confined to the cytoplasm (Fig. 2F). No labeling of the plasma membrane was observed. To eliminate the possibility of cross-reactivity with HR1, HR2 antibody was also tested in transfected cells that express HR1; no immunolabeling was observed (Fig. 2E).

Immunolabeling

A total of 30 pairs of macaque eyes, including 13 from M. mulatta, and 17 from M. fascicularis, were obtained and processed as described above. Pieces of the eyecups were immersion fixed in 0.1M PB, pH 7.4, containing various mixtures of aldehydes. The optimal conditions for labeling with anti-HR2 were retinas fixed with a mixture of 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% glutaraldehyde for 1 to 2 hours at 20°C. However, similar patterns of HR2 immunolabeling were also observed in tissue fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15–30 minutes at 20°C. The fixed retinas were isolated from the retinal pigment epithelium and rinsed five times in 0.1M PBS. Retinas fixed with glutaraldehyde were incubated in a solution of 1% sodium borohydride in PBS for 1 hour. Otherwise, labeling procedures were the same as described above.

Vibratome sections or flat mounts were incubated in primary antisera at 4°C with 1% donkey serum in PBSa or else 5% Chemiblock. Sections were incubated for 5–7 days and flat mounts were incubated for 12 days or more. In addition to goat antibodies against HR2 (1:2,000–1:5,000), the tissue was double- or triple-labeled using mouse monoclonal antibody 7G6, which was made against a crude extract of monkey retina and was later discovered to recognize cone arrestin (1:1,000; Zhang et al., 2003), rabbit polyclonal antiserum, U2656, raised against a purified glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein containing the entire B domain of rat ribeye (1:500, gift of Dr. Thomas Südhof; Schmitz et al., 2000) against the C-terminal peptide (KATSTVAAPPKGEDAEAHK) of human metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 (mGluR6; 1:500, gift of Dr. Noga Vardi; Vardi et al., 2000), affinity-purified polyclonal rabbit antibody against the C-terminus (RQSSGLAVIASDLP) of rat glutamate receptor subunit 4 (GluR4; 1:500, Millipore), and affinity-purified syntaxin 3 specific antibody generated in rabbits against a peptide from the N-terminus of mouse syntaxin 3 KDRLEQLKAKQLTQDDC, an epitope conserved in primates (1:500, gift of Dr. Roger Janz). Fluorescein peanut agglutinin (Vector Laboratories), a specific marker for cones (Blanks et al., 1988), was used at 1:400 dilution. Sections were incubated in secondary antibodies as described above. Both whole mounts and sections were placed on glass slides and coverslipped in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) mounting medium with DAPI.

Antibody characterization

Several additional antibodies were used as markers for specific cell types or for synaptic structures. In every case, their specificity was demonstrated using western blots, and they reproduced the pattern of labeling described previously in primate or other mammalian retinas.

The parvalbumin monoclonal antibody recognized a single band of 12 kDa on western blots of rat brain (Celio et al., 1988). The parvalbumin antibody reproduced the pattern of labeling described previously using calretinin antibodies in macaque retina; it labeled macaque horizontal cells and a type of broadly stratified amacrine cell (Klump et al., 2009).

The tryosine hydroxylase monoclonal antibody recognized a single band at 60 kDa on western blots of cultured rat adrenal pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells (pers. commun., Sigma-Aldrich technical support). It reproduced the pattern of labeling described previously using tyrosine hydroxylase antibodies in primate retinas; that is, it labeled a type of wide-field amacrine cell (Casini et al., 2006).

The calretinin antiserum recognized a single spot at the predicted molecular weight (29 kDa) and isoelectric point (5.3) of calretinin on 2D gels of rat brain or cochlear nucleus (Winsky and Jacobowitz, 1991a,b). It reproduced the pattern of labeling described previously using calretinin antibodies in macaque retina; that is, broadly stratified amacrine cells were labeled (Kolb et al., 2002).

The arrestin monoclonal antibody recognized a single band of 50 kDa on western blots of human retina. It reproduced the pattern of labeling described previously in macaque retina; it labeled cones in their entirety (Zhang et al., 2003).

The ribeye antiserum recognized only two bands on western blots of bovine retina, one at 120 kDa corresponding to the predicted molecular weight of ribeye and one at 50 kDa corresponding to the predicted molecular weight of CtBP2, which has a structure identical to that of the B domain of ribeye (Schmitz et al., 2000). Antisera against ribeye had never been used previously in primate retinas, but the pattern of labeling was identical to that observed in other mammalian retinas; it labeled synaptic ribbons in both the outer and inner plexiform layers (Katsumata et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2009).

The mGluRr6 antibody recognized a single band of 190 kDa in western blots of monkey retina (Vardi et al., 2000). It reproduced the pattern of labeling described previously in macaque retina; it labeled the tips of macaque ON bipolar cell dendrites (Gastinger et al., 2006).

The GluR4 antibody recognized a single band of 100 kDa on western blots of rat brain (manufacturer’s datasheet). The pattern of labeling observed in the macaque outer plexiform layer with this antibody was the same as that described previously in the human retina using antibody to GluR4 (Santiago et al., 2008).

The syntaxin 3B antibody recognized a single band of 37 kDa in western blots of mouse retina (R. Janz, pers. commun.). The antibody had never been used in primate retinas. However, the pattern of labeling observed was identical to that described previously in mouse retina; that is, ribbon synapses of photoreceptors and bipolar cells were labeled (Sherry et al., 2006).

Control experiments

Macaca mulatta retinas were fixed with 0.1% glutaraldehyde/ 4% paraformaldehyde 0.1M PB pH 7.4 for 2 hours at 20°C, treated with NaBH4 and graded ethanol solutions, and 50-µm vibratome sections were cut. Control experiments were done in parallel, incubating sections with HR2 IgG alone diluted at 1:5,000 for 48 hours at 20°C. HR2 immunolabeling was blocked by preadsorption of antibody (1:5,000) with KLH-conjugated peptide (1 mg/ml). To determine whether the HR2 antibody was reacting with the carrier protein, a control experiment was repeated with an excess of synthetic KLH alone (80 µg/ mL); the labeling was not blocked. Sections incubated in parallel with untreated anti-HR2 yielded positive results.

Horizontal cell injection with Neurobiotin

Horizontal cells were injected iontophoretically with Neurobiotin (Vector Laboratories) in pieces of living macaque retina. Eyecups from four macaques including three M. mulatta and one M. fascicularis were used for this experiment. The time from enucleation until the experiment ranged between 30 minutes and 1 hour. Under room light the eyecups were cut into small pieces (5 × 5 mm), the retina isolated and placed on a black membrane filter paper, ganglion cell side-up while being superfused in carboxygenated Ames medium on an upright, fixed stage microscope Olympus BX50WI microscope (Tokyo, Japan). Unused pieces were stored at room temperature in carboxygenated Ames medium and kept in the dark. Pieces of retina were prelabeled with DAPI in Ames medium with 95% oxygen/5% CO2 at ambient temperature for 30 minutes. Glass microelectrodes pulled with a Flaming- Brown horizontal micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA), tip-filled with a mixture of 0.5% Lucifer Yellow-CH (L-453, Invitrogen) and 3.5% Neurobiotin in 0.05M PBS, and backfilled with 3M LiCl. The electrode resistance was between 50–100 MΩ. Horizontal cell somas were targeted based on the intensity of DAPI staining. Single type 1 horizontal cells were targeted under visual control with a 40× water immersion objective. Several cells in each piece of retina were injected with 1 nA negative current using a Warner Instruments (Hamden, CT) 1 E-210 amplifier for 5 minutes and tracer was allowed to diffuse for 30 minutes at 35°C before fixation. After the last injection, retinal pieces were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes and washed several times in PBS. Neurobiotin was visualized by incubating retinas with Alexa 488-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson) 1:500 overnight using the same diluents as for the secondary antibodies.

Electrophysiology

Seven macaques were used, in all, including five M. mulatta and two M. fascicularis. The methods for preparing retinal slices and recording in whole-cell voltage clamp mode with patch electrodes were the same as described in a recent article from this laboratory, except that cones were targeted (Yu et al., 2009). Briefly, slices were continuously superfused at 2.5 ml/min; at this rate, the chamber volume was replaced after 20 seconds. The extracellular solution was bicarbonate-buffered Ames medium (Sigma- Aldrich) adjusted to 300 mOsm with sucrose and equilibrated with 95% O2 / 5% CO2. The slices were maintained at 33°C. The pipette solution contained (in mM): 126 K-Gluconate, 4 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 1.1 EGTA, 10 Na-HEPES, 3 Mg-ATP, and 0.5 Na-GTP; the pH was adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. The data were corrected for a 2 mV liquid junction potential. Capacitance was compensated automatically using Patchmaster software (Heka Elektronik, Bellmore, NY). The cone membrane was held at −58 mV, and command voltages were applied in −10 mV steps from −58 mV to −98 mV for 500 ms. Then 5 µM histamine was added to the superfusate and after 1 minute the procedure was repeated. The measurements were made again after a Histamine receptors of monkey retina 5-minute washout with normal Ames medium. Data were analyzed using Igor Pro v. 5 (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Paired t-tests were used to compare the currents before and after histamine application were done using SigmaPlot v. 9 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

In situ hybridization

Human cDNA clones coding for histamine receptor 1 (accession number: BC060802), and histamine receptor 2 (accession number: BC054510) were used to generate digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes. Approximately 200 bp portions of the coding regions of the cDNA sequences were amplified by PCR with T7 or T3 RNA polymerase promoter sequences included in the primers. Primers for HR1 were cgtaatacgactcactatagggcgacgctcgcattcaagacagta (forward) and caattaaccctcactaaagggaagggtggttcagacactggtt (reverse). Primers for HR2 were cgtaatacgactcactatagggcgaaccagcaagggcaatcatac (forward) and caattaaccctcactaaagggaatcatgtgagcttcaggcaac (reverse). Sense and antisense riboprobes were generated by in vitro transcription from the PCR products using a Dig-RNA labeling kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). In situ hybridization was performed in a baboon (Papio anubis) retina obtained through the Tissue Distribution Program at the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research (San Antonio, TX) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours. The tissue was embedded flat in a block of 1% agarose, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 13 µm. In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (O’Brien et al., 2004). Briefly, the sections were dewaxed with xylene, digested with 40 µg/ml proteinase K (Pierce) in 100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 25 mM EDTA for 10 minutes at 37°C, postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes, and acetylated with 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 M triethanolamine, pH 8.0 for 10 minutes. Sections were prehybridized with hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 750 mM NaCl, 75 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0, 10% dextran sulfate, 0.02% Ficoll, 0.02% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 10 µg/ml bovine serum albumin, 10 mM DTT, 1 mg/ml salmon sperm DNA) at 50°C for 2 hours and then hybridized with probes in the same solution at 50°C overnight. Hybridized sections were washed three times for 30 minutes each with washing buffer (50% formamide, 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0, 1% SDS) at 50°C. Sections were treated with 2% H2O2 in PBS for 10 minutes to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. The slides were then incubated with peroxidase-conjugated anti-DIG antibody (Roche) 1:400 in PBS, 0.3% Triton X-100 without sodium azide (Sigma) and TNB blocking buffer (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT) overnight at room temperature. After being washed five times (10 minutes each) with PBS, 0.3% Triton X-100, hybridization signals were visualized by incubating with Cy3 Tyramide (TSA Fluorescence System, Invitrogen) at 1:100 in PBS for 5 minutes at room temperature and counterstained with TO-PRO-3 (Molecular Probes). Digital fluorescent images were acquired and processed as described above.

RESULTS

In situ hybridization

To determine the cell-type specificity of histamine receptor expression in the retina, we carried out in situ hybridization on sections through the central baboon retina (Fig. 1). HR1 antisense probe labeling was confined to perikarya and dendrites of horizontal cells. Horizontal cell perikarya were identified by their position in the outer row of the inner nuclear layer (INL). All perikarya in that row were lightly labeled. The labeling was more intense in horizontal cell primary dendrites, identified by their relatively large diameter and oblique course through the neuropil. HR2 antisense probe labeled the inner segments of cones, which were identified by their characteristic shape and position.

Figure 1.

Baboon retinal sections labeled with sense and antisense probes against human HR1 and HR2. Nuclear counterstaining was done with TO-PRO-3 iodide stain (Molecular Probes; blue). There was no labeling with HR1 (A,B) and HR2 (F–G) sense probes. HR1 antisense probe labeling (green) was most prominent in dendrites of horizontal cells (C). Image is a 6-µm confocal stack. The area in the square is shown at higher magnification (E). Perikarya in the outermost row of the INL (arrows) were also labeled. Image is an 8-µm confocal stack. HR2 antisense probe labeling was found in cone photoreceptors (H, green). Image is a 7-µm confocal stack. The area in the square is shown at higher magnification (J). Cone inner segments were labeled. Image is a 5-µm confocal stack. ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. Scale bars = 20 µm in A–D,F–I; 10 µm in E,J. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Development of new HR1 and HR2 antibodies

We developed antibodies against synthetic peptides corresponding to an extracellular loop of human HR1 and a C-terminal (cytoplasmic) epitope of human HR2. The HR1 antibody was affinity-purified against its peptide target; the HR2 antibody was protein G-purified. Both antibodies labeled GST fusion proteins containing the targeted domains in western blots (Fig. 2). The HR1 antibody labeled HeLa cells transfected with the full-length human HR1 cDNA but not HeLa cells transfected with the full-length human HR2 cDNA. In contrast, the HR2 antibody did not label HeLa cells transfected with the HR1 cDNA but did label cells transfected with HR2 cDNA. Thus, both antibodies labeled their native histamine receptor targets and did not crossreact with other histamine receptors.

Most immunoreactive HR1 is in the outer row of the inner nuclear layer

The majority of the HR1-immunoreactive (IR) cells were in the outermost row of the INL and had the morphology characteristic of primate horizontal cells (Polyak, 1941). The horizontal cells were not completely labeled. HR1 immunoreactivity was granular and typically confined to the perinuclear cytoplasm and the bases of dendrites (Fig. 3). In some instances, higher-order dendrites were labeled, but their branching was difficult to visualize. It was clear that dendritic terminals were not labeled. Fine, unbranched axons emerging from the perikarya, but distinct from the dendrites, were also labeled; however, axon terminals were unlabeled (Boycott and Kolb, 1973).

Figure 3.

Localization of HR1 and parvalbumin (PV) in a vertical section. Single optical section of central retina. A: HR1 immunoreactivity (red) was confined to perinuclear cytoplasm and the bases of primary dendrites in the outermost row of the INL. Occasionally, there were labeled cells in the innermost row of the INL (arrowhead). The fine unbranched process (large arrow) is a horizontal cell axon. The labeling in the optic fiber layer was not specific. B: PV-positive (green) horizontal cell bodies exist in precise register with HR1 immunolabeled cells. DAPI staining (blue) indicated that both types of horizontal cells expressed HR1. Arrows indicate labeling of dendritic tips, which did not contain immunoreactive HR1. GCL, ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer. Scale bar = 20 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Histamine receptor 1 is localized in perikarya of horizontal cells

To confirm that HR1 was expressed by horizontal cells, sections were processed for double-labeling experiments with antibodies to parvalbumin (PV; Wassle et al., 2000). HR1-immunolabeled cells in the outer row of the INL were also PV-positive (Fig. 3). Sections were also labeled with nuclear marker DAPI. In all instances, DAPI-labeled nuclei in the outermost row of the INL were surrounded by immunoreactive HR1. HR1 immunolabeling was also found in PV-immunoreactive ascending dendrites, but, there was no HR1-immunoreactivity in horizontal cell dendrites.

Histamine receptor 1 is also localized in amacrine cells

A few cells that expressed HR1 had cell bodies in the innermost row of the INL and were tentatively identified as amacrine cells (Fig. 4). HR1-IR amacrine cells were very sparse; there were never more than two cells in each 50-µm vertical section. The cell bodies were ovoid in shape, with the long axis vertically. The average soma diameter (short axis) of HR1-IR cells in mid-peripheral and central retina was 9.2 ± 1.2 µm (n = 18). HR1-IR amacrine cell bodies were only found in 9 out of 21 retinas fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium PB, pH 7.4 for 2 hours, including seven M. mulatta, and two M. fascicularis. HR1-expressing cells were never displaced to the ganglion cell layer (GCL). The granular immunoreactivity was confined exclusively to the cytoplasm and primary dendrites of the cells (Fig. 4). HR1-IR amacrine cells had one or two primary dendrites, whose average diameter was 1–2 µm. Because higher order dendrites were not labeled, it was impossible to identify these cells by their stratification patterns in the IPL. The HR1-IR amacrine cells did not contain immunoreactive PV (Figs. 3, 4), tyrosine hydroxylase, or calretinin (not illustrated).

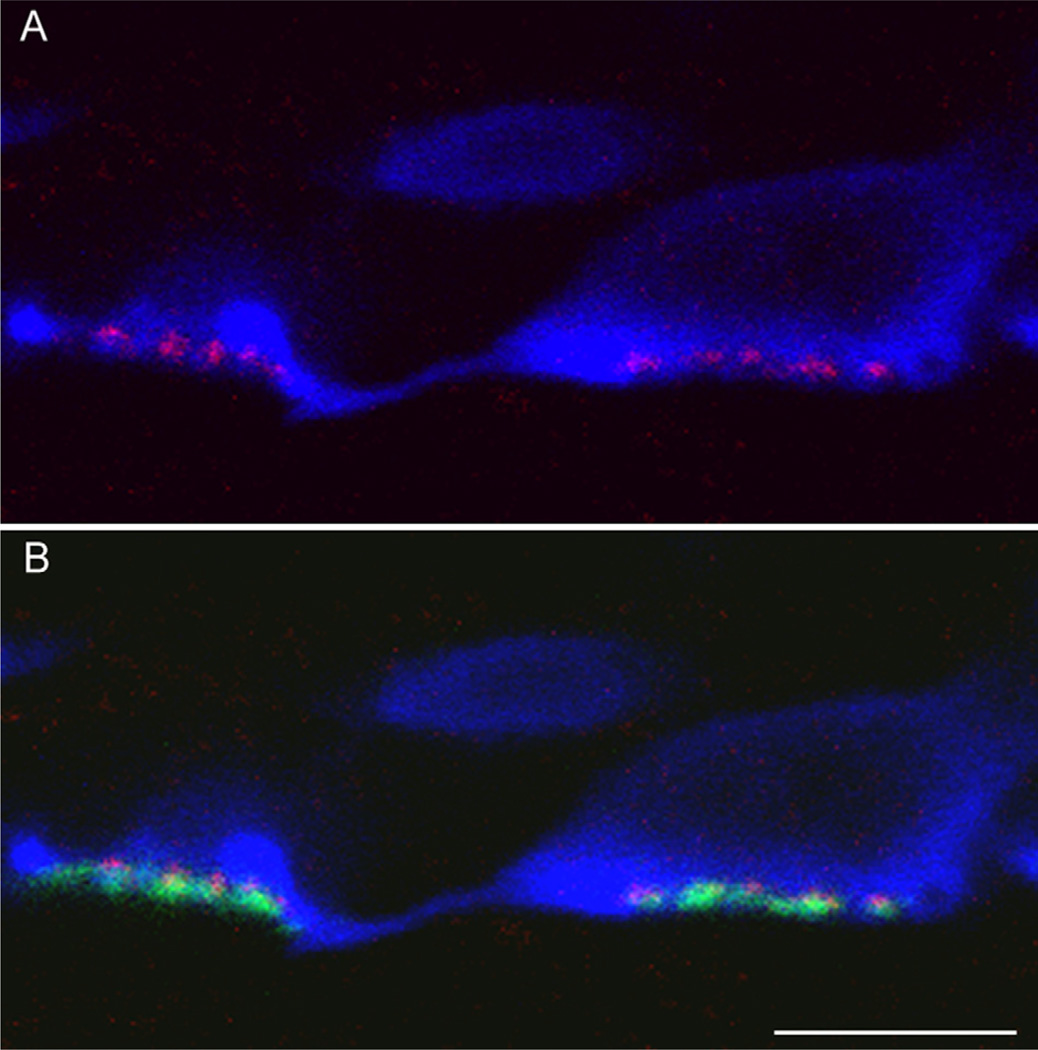

Figure 4.

HR1 localization in amacrine cells. A: Immunoreactive HR1 (magenta) was also found to somata in the innermost row of the inner nuclear layer. HR1-expressing cells contained granular immunoreactivity confined exclusively to the cytoplasm. B: Double-label experiments showed that HR1-immunoreactive amacrine cells did not contain immunoreactive parvalbumin (green). IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer. Scale bar = 20 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Histamine receptor 2 immunoreactivity is localized to cone pedicles

Immunoreactive HR2 was found in the outer margin of outer plexiform layer (OPL). In vertical sections of tissue fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at 4°C, the labeling was granular in appearance and uniformly distributed within the cone pedicles. HR2 labeling was found to be very inconsistent under these conditions; however, it was seen only in one out of five attempts. Punctate HR2 labeling was more consistently found in tissue fixed in a mixture of 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% glutaraldehyde for 2 hours (Fig. 5). The puncta were round, averaging 0.40 µm in diameter, and were found in the lower part of each cone pedicle. No labeling was associated with rod spherules.

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescent localization of HR2 in cone pedicles. A single optical section is shown. The tissue was double-labeled with antibody to HR2 (red) and antibody 7G6 against cone arrestin (blue). A: The entire cone was labeled with antibody 7G6. HR2 labeling with a punctate distribution was present in cone pedicles. B: HR2 immunoreactivity appeared as discrete puncta in the OPL. C: High-power micrograph showing superposition of HR2 and 7G6 labeling in the base of the cone pedicle. Telodendria were also labeled (arrowhead). Scale bar = 20 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

The identity of the cones was confirmed with two specific markers, the lectin peanut-agglutinin (PNA) which labels the cone cell membrane (Mitchell et al., 1999), and monoclonal antibody 7G6 against cone arrestin, a marker that labels the cytoplasm of all cones (Zhang et al., 2003). HR2 labeling with punctate distribution was only present in structures also labeled with antibody 7G6 (Fig. 5). In single optical sections labeled with 7G6, invaginations in the cone pedicle bases were observed, and HR2-IR puncta were located above each invagination in the cone pedicle bases (Figs. 6, 7). They were also located slightly above the PNA labeling. Taken together, these findings suggest that HR2-IR puncta are inside cone pedicles and not in their plasma membranes.

Figure 6.

Optical section of flat-mounted retina double-labeled for HR2 and antibody 7G6 against cone arrestin. A: HR2 immunoreactivity (red) appeared as discrete puncta in the lowest part of the cone pedicles. B: Cone pedicles are labeled using antibody 7G6 (blue). HR2 labeling with punctate distribution occupied the invaginations in the bases of the cone pedicles. Scale bar = 5 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Figure 7.

Immunofluorescent localization of HR2, arrestin, and peanut agglutinin (PNA) in cone pedicles. A single optical section is shown. A: Punctate HR2 immunoreactivity (red) was found in invaginations of the cone pedicles (blue). B: A section double-labeled with PNA (green), a specific marker for the cone plasma membrane. HR2 and PNA are closely associated but not colocalized. Note that the immunoreactive HR2 is located above the cone plasma membrane. Scale bar = 5 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

To determine whether HR2 was expressed in the plasma membrane of the cones, retinas were labeled with antibodies to syntaxin 3, a membrane protein expressed by cones that is a component of the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex at ribbon synapses (Morgans et al., 1996). Syntaxin 3 labeling was found in the membranes of inner segments, cell bodies, and axon terminals of photoreceptors (Curtis et al., 2008). There was particularly strong syntaxin 3 labeling in the synaptic terminals (Fig. 8). Single optical sections through cone pedicles double labeled with HR2 and syntaxin 3 antibodies showed that the two were closely associated but not colocalized. HR2 puncta were located slightly above the plasma membrane, a finding also suggesting that HR2 is inside cone pedicles and not in their plasma membranes.

Figure 8.

Cone pedicles that were double-labeled for HR2 and Syntaxin 3. A: Single optical section through four cone pedicles labeled with HR2 antibody. The HR2-positive puncta are localized at the bases of cone pedicles (magenta) B: Syntaxin 3 immunoreactivity in plasma membranes of cone pedicles (green). HR2-IR puncta are located slightly above the syntaxin 3-positive membranes. Scale bar = 5 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

To determine whether HR2 was associated with synaptic ribbons in the cone, double-labeling studies were performed using an antibody to the protein ribeye, a component of synaptic ribbons (Schmitz et al., 2000). Single optical sections showed ribbons labeled with the antibody to ribeye and HR2-IR puncta clustered within the cone pedicles (Fig. 9). The puncta were closely associated with synaptic ribbons, but ribeye and HR2 were not colocalized. One punctum was typically found per ribbon.

Figure 9.

Horizontal section of a cone pedicle double-labeled with antibodies to HR2 and ribeye. A: Single optical section showing HR2-IR puncta in a cone pedicle (magenta). B: Ribbons labeled with antibody to ribeye (green) were associated with synaptic ribbons, but there was very little overlap (white). No HR2-IR puncta were associated with rods indicated by the longer synaptic ribbons. Scale bar = 5 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Histamine receptor 2 is not localized to horizontal or bipolar cells

To rule out the possibility that HR2 was associated with ON bipolar cell dendrites, the central elements of the triads, double-labeling studies were performed using an antibody to metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 (mGluR6), a specific marker for ON bipolar cell dendrites (Vardi et al., 2000). ON bipolar cell dendrites formed 0.2– 0.5 µm clusters (Fig. 10). ON bipolar cell dendrites were closely associated with HR2-IR puncta, but the two were not colocalized. The HR2-IR puncta were always located above the ON bipolar cell dendrites, as expected if they were within the cone pedicles.

Figure 10.

Cone pedicle triple-labeled with antibodies to HR2, 7G6, and mGluR6. Single horizontal optical section through the cone pedicle is shown. A: HR2-IR puncta (red) were found within 7G6-IR cones (blue). Immunoreactive mGluR6, a specific marker for ON bipolar cell dendrites (green) was also localized to puncta inside invaginations of the cone pedicle, but these were not colocalized with puncta containing immunoreactive HR2 (red), though the two were associated. B: A single vertical optical section of the OPL labeled with antibody to HR2 is shown. HR2 immunoreactivity (red) with punctate distribution was found in invaginations of this cone pedicle. C: The same section double-labeled with mGluR6 (green) shows both structures closely associated but not colocalized. Magenta and green copies of panels B and C are available as a Supplementary Figure 1. Note that the immunoreactive HR2 is located above the ON bipolar cell dendrites. Scale bars = 5 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

To rule out the possibility that HR2 was expressed by horizontal cell dendrites, the lateral elements of the triads, two complementary approaches were used. The first approach consisted of visualizing cell bodies of type 1 horizontal cells with DAPI and filling them with Neurobiotin using intracellular electrodes (Fig. 11). If Neurobiotinfilled horizontal cells express immunoreactive HR2 on the tips of their dendrites, the two markers would be colocalized. The lateral elements of the triads formed by the Neurobiotin-filled dendrites were associated with HR2-IR puncta, but the two markers were not colocalized.

Figure 11.

Distribution of HR2 immunoreactivity relative to horizontal cell dendrites in the OPL. A: A single type 1 horizontal cell was filled with Neurobiotin. A stack from 17 single optical sections at 0.50 µm increments is shown (green). B: A single optical section imaged at the level of the OPL at higher magnification. Puncta containing immunoreactive HR2 (magenta) were closely associated with horizontal cell dendrites, but the two were not colocalized. Scale bars = 20 µm in A; 1 µm in B. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

The second approach was to compare the localization of HR2 with glutamate receptor 4 (GluR4), an alphaamino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA) receptor subunit expressed on horizontal cell dendrites (Harvey and Calkins, 2002; Shen et al., 2004). There were two GluR4-IR bands in sections imaged through the OPL, as described previously (Haverkamp et al., 2001). The inner band labeled with GluR4 was below the cone pedicle bases (Figs. 12, 13). This band represents a clustering of the AMPA receptor subunit at the desmosome-like junctions beneath the cone pedicles (Haverkamp et al., 2001). There was no HR2 labeling associated with the inner band. The outer band was found within the invaginations of the cone pedicles and corresponded to lateral elements in the triads (Haverkamp et al., 2001). HR2-IR puncta were always found above the outer band of GluR4-IR puncta, confirming that the puncta were in cone pedicles, not in horizontal cell dendrites.

Figure 12.

Localization of HR2 puncta in the pedicle with respect to horizontal cell dendrites using an AMPA receptor subunit (GluR4) expressed on the tips of horizontal cell dendrites. A: Punctate GluR4 immunoreactivity (green) is closely associated with the HR2 (magenta). B: Optical section located closest to the inner segment was exclusively labeled with HR2 (magenta) and showed no colocalization with GluR4. Scale bar = 5 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Figure 13.

Expression of GluR4 and HR2 at the cone pedicle base. A: Single optical section through 3 cone pedicles immunostained for HR2 (magenta). B: Two bands of GluR4 labeling (green) in the OPL at three cone pedicles. C: double labeling shows that the top band of GluR4 is closely associated, but not in register with HR2 immunoreactive puncta. OPL, outer plexiform layer. Scale bar = 5 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Histamine effects on Ih of cones

The effect of histamine on hyperpolarization activated inward current (Ih) was studied using patch electrodes in the whole-cell, voltage-clamp mode in seven macaque retinal slice preparations (Fig. 14). The cone membrane was held at −58 mV, and command voltages were applied in −10 mV steps from −58 mV to −98 mV. At the −68 mV command voltage, cones showed a prominent inward current. The application of 5 µM histamine in the superfusate reversibly reduced the amplitude of this current by 20% under these conditions, on average. A smaller, but statistically significant, decrease in Ih was observed at −78 mV as well (P < 0.05). At more hyperpolarized potentials, however, Ih was the same before and after histamine application. The maximum amplitude of the current was also unchanged. Taken together, these results suggest that histamine shifts the activation function of Ih to more hyperpolarized potentials.

Figure 14.

Hyperpolarization-activated currents recorded from a macaque cone in the whole-cell, voltage-clamp mode. A: The holding potential was −58 mV, and the membrane potential was stepped to −68 mV. The amplitude of the current was reduced by 5 µM histamine (HA), and the effect was reversible (Wash). B: Averaged current-voltage plots from the seven macaque cones. At −68 mV and −78 mV (asterisks), the hyperpolarization activated cation currents were significantly reduced (P < 0.05) after application of 5 µM histamine (open circles) compared with control (closed circles). Bars indicate the standard error of the mean.

DISCUSSION

HR1 is expressed in horizontal cells and a subset of amacrine cells

The first major finding was that HR1 were expressed in baboon horizontal cells, and the receptor was localized to cell bodies, primary dendrites, and axons of horizontal cells in the macaque retina. These findings suggest that histamine would influence both rod and cone pathways via HR1. However, there was no immunoreactive HR1 in axonal or dendritic terminals, a finding suggesting that the antibody either recognizes a precursor of the receptor or detects receptor that is contained in an internal compartment due to receptor recycling. This is the first time HR1 has been localized in a primate retina and the first time any histamine receptor has been found in horizontal cells.

Histamine release is maximal during the day in primates (Prell et al., 1989), and therefore it is expected to optimize the function of the retina in bright ambient light. HR1 activation typically stimulates phospholipase C (PLC), which releases calcium ions from internal stores (Brown et al., 2001); PLC has not been localized in primate retinas, but it is found in other mammalian horizontal cells. A retina-specific isoform, PLC beta 4, has been identified (Lee et al., 1993) and localized to bovine horizontal cells, among other cell types (Ferreira and Pak, 1994). PLC beta 4 was localized to horizontal cells in mouse retina, and PLC beta 4-knockout mice had visual deficits and reductions in the electroretinogram (Jiang et al., 1996). PLC gamma 1 has also been localized to horizontal cells in mice (Peng et al., 1997).

When HR1 on primate horizontal cells are activated by histamine, they might enable the retina to respond to light stimuli at higher temporal frequencies. In humans, HR1 antagonists, the classical antihistamines, decrease the critical flicker fusion frequency (Nicholson, 1982; Nicholson and Stone, 1983). The responses of macaque parasol ganglion cells to luminance flicker are identical to those of human subjects under the same conditions (Lee et al., 1989), and horizontal cells make a major contribution to the receptive field surrounds of parasol cells (McMahon et al., 2004; Davenport et al., 2008). According to this hypothesis, histamine acting via HR1 would make the light responses of the horizontal cells larger or faster and have similar effects on the receptive field surrounds of parasol cells.

Horizontal cell axon terminals make synapses onto rod spherules and rod bipolar dendrites in primates (Linberg and Fisher, 1988). Horizontal cell axon terminals in rod spherules of rodents contain vesicular GABA transporter, a finding suggesting that they release GABA by a calcium-dependent mechanism (Cueva et al., 2002; Guo et al., 2010). In other mammalian retinas, horizontal cells express the proteins associated with calcium-dependent neurotransmitter release, including: complexin, syntaxin, synapsin, and SNAP-25 (Hirano et al., 2005, 2007; Lee and Brecha, 2010; Deniz et al., 2011). If stimulation of HR1 increases intracellular levels of calcium in primate horizontal cells, this would be expected to enhance synaptic transmission.

Macaque horizontal cells are electrically coupled (Dacey et al., 1999), and another possibility is that histamine modulates coupling via HR1, as described previously in the hypothalamus (Hatton and Yang, 1996). Elevated levels of intracellular calcium in horizontal cells might also stimulate nitric oxide synthase (Brown et al., 2001), releasing nitric oxide, which, in turn, uncouples gap junctions (Xin and Bloomfield, 2000). Because Ca2+ can diffuse freely through gap junctions, coupling of horizontal cells would allow for intercellular signal transmission within the layer of horizontal cells (Schubert et al., 2006).

HR1 was also localized to amacrine cells whose cell bodies resembled those of spiny amacrine cells described using the Golgi method (Mariani, 1990; Kolb, 1992). There is evidence of HR1 expression in dopaminergic amacrine cells in rat (Gastinger et al., 2006) and mouse (Greferath et al., 2009) retinas. However, the HR1-IR cells in macaque retina did not contain immunoreactive tyrosine hydroxylase.

HR2 is expressed in cone pedicles

The second major finding was that HR2 was expressed by cones in macaque and baboon retinas. This was the first time that HR2 had been localized anywhere in the central nervous system using immunolabeling methods. HR2 was localized to puncta closely associated with the synaptic ribbons, one per ribbon. Given that HR2 is a membrane protein, these results suggest that HR2 has been internalized, possibly after binding to histamine. It is also possible that such receptors are internalized constitutively (Scarselli and Donaldson, 2009). The HR2 in cones may, nevertheless, be active. Another G-protein-coupled receptor can stimulate production of cAMP after internalization, and this effect is independent of receptor activation (Calebiro et al., 2009). It was not possible to identify the compartment in which the HR2 was expressed in macaque retina; two possibilities are recycled plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum. Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 (SERCA2) immunoreactive puncta are closely associated with ribeye, and in electron micrographs endoplasmic reticulum is closely associated with synaptic ribbons (Babai et al., 2009). Macaque cones also contain immunoreactive SERCA2 (Krizaj, 2005), and there might be a similar association of endoplasmic reticulum with synaptic ribbons.

The hyperpolarization activated cation current (Ih) in macaque cones was reduced by histamine. This is a prominent current mediated by hyperpolarization and cyclic nucleotide gated (HCN) channels. Ih is activated by hyperpolarizations greater than −65 mV and produces an inward current that drives the membrane potential of the cone back toward its dark value, around −40 mV. Its function is to limit the amplitude and duration of the cone’s hyperpolarization to light and thus to enhance the frequency response of the cones (Yagi and MacLeish, 1994; Kawai et al., 2002; Barrow and Wu, 2009). In 5 µM histamine, this current was reduced in amplitude by as much as 20% at moderately hyperpolarized membrane potentials, but not at more hyperpolarized potentials. Because the maximum amplitude of the current was also unaffected, these findings suggest that the activation voltage of Ih was shifted to more hyperpolarized potentials. In mouse rods, Ih contributes significantly to ATP utilization (Okawa et al., 2008), and the same should be true for primate cones. If so, the shift in the activation function of Ih would conserve ATP in bright ambient light. The reduction in Ih might also enhance voltage-gated sodium currents, as reported in human cones (Kawai et al., 2005). Sodium action potentials mediated by these currents are thought to enhance the release of glutamate after bright lights are turned off and to rapidly terminate the voltage responses (Ohkuma et al., 2007). A similar reduction of Ih mediated via D2 receptors was recently described in human rods. Unlike the effect of histamine on macaque cones, however, the peak amplitude of the current was also decreased (Kawai et al., 2011).

HR2 acts through the cAMP-dependent PKA pathway (Brown et al., 2001), and this might act on a number of other targets within the cone pedicles as well. Primate cones are coupled to one another (Hornstein et al., 2004) and to rods (Hornstein et al., 2005), and it is possible that histamine modulates this coupling. Results using retinas from other mammals in vitro suggest that rod-cone coupling is weak during the day as a result of dopamine stimulating D4 receptors on cones (Ribelayga and Mangel, 2008). If dopamine also uncouples rods and cones in primates, its effects would be opposite to those predicted for histamine. One possibility, however, is that histamine and dopamine act in different compartments within the cones. According to this hypothesis, histamine acts near the neurotransmitter release sites, but dopamine acts on the telodendria, where connexin 36-IR plaques have been localized (O’Brien et al., 2004).

The cAMP generated by HR2 in cones might have an effect on cyclic nucleotide-gated CNG channels (Kaupp and Seifert, 2002). In chicken cones, cAMP increases the affinity of the channel for cGMP, and this would promote calcium influx through these channels (Ko et al., 2004). The combination of Ca2+ influx through cGMP-gated channels and voltage gated calcium channels allows exocytosis to be maintained over an extended voltage range (Rieke and Schwartz, 1994). cAMP might also act directly on voltage gated calcium channels (Stella and Thoreson, 2000), which are essential for the release of glutamate from primate cones (Yagi and MacLeish, 1994). In any case, the localization of HR2 very close to cone synaptic ribbons suggests a presynaptic role for the receptor.

CONCLUSIONS

HR1 was expressed by horizontal cells, and HR2 was closely associated with synaptic ribbons in cone pedicles. HR3 was previously localized on the tips of ON bipolar cell dendrites in both rod and cone terminals (Gastinger et al., 2006). Thus, all three histamine receptors have been identified in the OPL, but the retinopetal axons containing histamine terminate in the IPL (Gastinger et al., 1999). Taken together, these findings suggest that most effects of histamine released by retinopetal axons in the primate retina are mediated by volume transmission.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Roger Janz, Dr. Noga Vardi, and Dr. Thomas Südhof for donating antibodies used in this study and Dr. Samuel Wu, Dr. Stephen Massey, and Dr. Gordon Fain for valuable discussions.

Grant sponsor: National Eye Institute; Grant numbers: EY06472 (to D.W.M.), EY012857 (to J.O.), core grant EY10608.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

LITERATURE CITED

- Airaksinen MS, Panula P. The histaminergic system in the guinea pig central nervous system: an immunocytochemical mapping study using an antiserum against histamine. J Comp Neurol. 1988;273:163–186. doi: 10.1002/cne.902730204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimov NP, Marshak DW, Frishman L, Glickman RD, Yusupov GR. Histamine reduces flash sensitivity of ON retinal ganglion cells in primate retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babai N, Morgans CW, Thoreson WB. Calcium-induced calcium release contributes to synaptic release from mouse rod photoreceptors. Neuroscience. 2009;165:1447–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow AJ, Wu SM. Low-conductance HCN1 ion channels augment the frequency response of rod and cone photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5841–5853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5746-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boycott BB, Kolb H. The horizontal cells of the rhesus monkey retina. J Comp Neurol. 1973;148:115–139. doi: 10.1002/cne.901480107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Stevens DR, Haas HL. The physiology of brain histamine. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:637–672. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calebiro D, Nikolaev VO, Gagliani MC, de Filippis T, Dees C, Tacchetti C, Persani L, Lohse MJ. Persistent cAMP-signals triggered by internalized G-protein-coupled receptors. PLoS Biol. 2009;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000172. e1000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casini G, Rickman DW, Brecha NC. Expression of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) plasma membrane transporter-1 in monkey and human retina. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1682–1690. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio M, Baier W, Schärer L, De Viragh PA, Gerday CH. Monoclonal antibodies directed against the calcium binding protein parvalbumin. Cell Calcium. 1988;9:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(88)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cueva JG, Haverkamp S, Reimer RJ, Edwards R, Wässle H, Brecha NC. Vesicular gamma-aminobutyric acid transporter expression in amacrine and horizontal cells. J Comp Neurol. 2002;445:227–237. doi: 10.1002/cne.10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis L, Datta P, Liu X, Bogdanova N, Heidelberger R, Janz R. Syntaxin 3B is essential for the exocytosis of synaptic vesicles in ribbon synapses of the retina. Neuroscience. 2010;166:832–841. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacey DM. Primate retina: cell types, circuits and color opponency. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:737–763. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport CM, Detwiler PB, et al. Effects of pH buffering on horizontal and ganglion cell light responses in primate retina: evidence for the proton hypothesis of surround formation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:456–464. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2735-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deniz S, Wersinger E, Schwab Y, Mura C, Erdelyi F, Szabó G, Rendon A, Sahel JA, Picaud S, Roux MJ. Mammalian retinal horizontal cells are unconventional GABAergic neurons. J Neurochem. 2011;116:350–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira PA, Pak WL. Bovine phospholipase C highly homologous to the norpA protein of Drosophila is expressed specifically in cones. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3129–3131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastinger MJ, O’Brien JJ, Larsen NB, Marshak DW. Histamine immunoreactive axons in the macaque retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:487–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastinger MJ, Yusupov RG, Glickman RD, Marshak DW. The effects of histamine on rat and monkey retinal ganglion cells. Vis Neurosci. 2004;21:935–943. doi: 10.1017/S0952523804216133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastinger MJ, Barber AJ, Vardi N, Marshak DW. Histamine receptors in mammalian retinas. J Comp Neurol. 2006;495:658–667. doi: 10.1002/cne.20902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greferath U, Kambourakis M, Barth C, Fletcher EL, Murphy M. Characterization of histamine projections and their potential cellular targets in the mouse retina. Neuroscience. 2009;158:932–944. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Hirano AA, Stella SL, Jr, Bitzer M, Brecha NC. Guinea pig horizontal cells express GABA, the GABA-synthesizing enzyme GAD 65, and the GABA vesicular transporter. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:1647–1669. doi: 10.1002/cne.22294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas H, Panula P. The role of histamine and the tubero-mamillary nucleus in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:121–130. doi: 10.1038/nrn1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey DM, Calkins DJ. Localization of kainate receptors to the presynaptic active zone of the rod photoreceptor in primate retina. Vis Neurosci. 2002;19:681–692. doi: 10.1017/s0952523802195137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton GI, Yang QZ. Synaptically released histamine increases dye coupling among vasopressinergic neurons of the supraoptic nucleus: mediation by H1 receptors and cyclic nucleotides. J Neurosci. 1996;16:123–129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00123.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp S, Grunert U, Wässle H. The synaptic architecture of AMPA receptors at the cone pedicle of the primate retina. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2488–2500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02488.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano AA, Brandstatter JH, et al. Cellular distribution and subcellular localization of molecular components of vesicular transmitter release in horizontal cells of rabbit retina. J Comp Neurol. 2005;488:70–81. doi: 10.1002/cne.20577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano AA, Brandstatter JH, et al. Robust syntaxin-4 immunoreactivity in mammalian horizontal cell processes. Vis Neurosci. 2007;24:489–502. doi: 10.1017/S0952523807070198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornstein EP, Verweij J, et al. Electrical coupling between red and green cones in primate retina. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:745–750. doi: 10.1038/nn1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornstein EP, Verweij J, et al. Gap-junctional coupling and absolute sensitivity of photoreceptors in macaque retina. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11201–11209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3416-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Lyubarsky A, Dodd R, Vardi N, Pugh E, Baylor D, Simon MI, Wu D. Phospholipase C beta 4 is involved in modulating the visual response in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14598–14601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BE. From waking to sleeping: neuronal and chemical substrates. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumata O, Ohara N, Tamaki H, Niimura T, Naganuma H, Watanabe M, Sakagami H. IQ-ArfGEF/BRAG1 is associated with synaptic ribbons in the mouse retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1509–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupp UB, Seifert R. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:769–824. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai F, Horiguchi M, Suzuki H, Miyachi E. Modulation by hyperpolarization-activated cationic currents of voltage responses in human rods. Brain Res. 2002;943:48–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai F, Horiguchi M, Ichinose H, Ohkuma M, Isobe R, Miyachi E. Suppression by an h current of spontaneous Na+ action potentials in human cone and rod photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:390–397. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai F, Horiguchi M, Miyachi E. Dopamine modulates voltage responses of human rod photoreceptors by inhibiting h current. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:4113–4137. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KE, Zhang AJ, Wu SM, Marshak DW. Parvalbumin-immunoreactive amacrine cells of macaque retina. Vis Neurosci. 2009;26:287–296. doi: 10.1017/S0952523809090075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko GY, Ko ML, Dryer SE. Circadian regulation of cGMP-gated channels of vertebrate cone photoreceptors: role of cAMP and Ras. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1296–1304. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3560-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H, Linberg KA, Fisher SK. Neurons of the human retina: a Golgi study. J Comp Neurol. 1992;318:147–187. doi: 10.1002/cne.903180204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H, Zhang L, Dekorver L, Cuenca N. A new look at calretinin-immunoreactive amacrine cell types in the monkey retina. J Comp Neurol. 2002;453:168–184. doi: 10.1002/cne.10405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizaj D. Serca isoform expression in the mammalian retina. Exp Eye Res. 2005;81:690–699. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyritsis A, Koh SW, Chader GJ. Modulators of cyclic AMP in monolayer cultures of Y-79 retinoblastoma cells: partial characterization of the response with VIP and glucagon. Curr Eye Res. 1984;3:339–343. doi: 10.3109/02713688408997218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labandeira-Garcia JL, Guerra-Seijas MJ, Gonzalez F, Perez R, Acuna C. Location of neurons projecting to the retina in mammals. Neurosci Res. 1990;8:291–302. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(90)90035-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Brecha NC. Immunocytochemical evidence for SNARE protein-dependent transmitter release from guinea pig horizontal cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:1388–1401. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BB, Martin PR, Valberg A. Amplitude and phase of responses of macaque retinal ganglion cells to flickering stimuli. J Physiol. 1989;414:245–263. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CW, Park DJ, Lee KH, Kim CG, Rhee SG. Purification, molecular cloning, and sequencing of phospholipase C-beta 4. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21318–21327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Masland RH, Strettoi E. Remodeling of cone photoreceptor cells after rod degeneration in rd mice. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:589–599. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linberg KA, Fisher SK. Ultrastructural evidence that horizontal cell axon terminals are presynaptic in the human retina. J Comp Neurol. 1988;268:281–297. doi: 10.1002/cne.902680211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning KA, Wilson, Uhlrich DJ. Histamine-immunoreactive neurons and their innervation of visual regions in the cortex, tectum, and thalamus in the primate Macaca mulatta. J Comp Neurol. 1996;373:271–282. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960916)373:2<271::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani AP. Amacrine cells of the rhesus monkey retina. J Comp Neurol. 1990;301:382–400. doi: 10.1002/cne.903010305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon MJ, Packer OS, Dacey DM. The classical receptive field surround of primate parasol ganglion cells is mediated primarily by a non-GABAergic pathway. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3736–3745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5252-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CK, Huang B, Redburn-Johnson DA. GABA(A) receptor immunoreactivity is transiently expressed in the developing outer retina. Vis Neurosci. 1999;16:1083–1088. doi: 10.1017/s0952523899166082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgans CW, Brandstatter JH, et al. A SNARE complex containing syntaxin 3 is present in ribbon synapses of the retina. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6713–6721. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06713.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson AN. Antihistaminic activity and central effects of terfenadine. A review of European studies. Arzneimittelforschung. 1982;32:1191–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson AN, Stone BM. The H1-antagonist mequitazine: studies on performance and visual function. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;25:563–566. doi: 10.1007/BF00542129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien J, Nguyen HB, Mills SL. Cone photoreceptors in bass retina use two connexins to mediate electrical coupling. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5632–5642. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1248-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkuma M, Kawai F, Horiguchi M, Miyachi EI. Patch-clamp recording of human retinal photoreceptors and bipolar cells. Photochem Photobiol. 2007;83:317–322. doi: 10.1562/2006-06-15-RA-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okawa H, Sampath AP, Laughlin SB, Fain GL. ATP consumption by mammalian rod photoreceptors in darkness and in light. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1917–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YW, Rhee SG, Yu WP, Ho YK, Schoen T, Chader GJ, Yau KW. Identification of components of a phosphoinositide signaling pathway in retinal rod outer segments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1995–2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak SL. The retina. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Prell GD, Khandelwal JK, Burns RS, Green JP. Diurnal fluctuation in levels of histamine metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid of rhesus monkey. Agents Actions. 1989;26:279–286. doi: 10.1007/BF01967291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribelayga C, Cao Y, Mangel SC. The circadian clock in the retina controls rod-cone coupling. Neuron. 2008;59:790–801. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieke F, Schwartz EA. A cGMP-gated current can control exocytosis at cone synapses. Neuron. 1994;13:863–873. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago AR, Hughes JM, Kamphuis W, Schlingemann RO, Ambrósio AF. Diabetes changes ionotropic glutamate receptor subunit expression level in the human retina. Brain Res. 2008;1198:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai S, Wang NP, Fukui H, Fukuda M, Manabe R, Wada H. Histamine H1-receptor in the retina: species differences. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;150:316–322. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90522-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarselli M, Donaldson JG. Constitutive internalization of G protein-coupled receptors and G proteins via clathrin-independent endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3577–3585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806819200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz F, Konigstorfer A, Südhof TC. RIBEYE, a component of synaptic ribbons: a protein’s journey through evolution provides insight into synaptic ribbon function. Neuron. 2000;28:857–872. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert T, Weiler R, Feigenspan A. Intracellular calcium is regulated by different pathways in horizontal cells of the mouse retina. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:1278–1292. doi: 10.1152/jn.00191.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Finnegan SG, Slaughter MM. Glutamate receptor subtypes in human retinal horizontal cells. Vis Neurosci. 2004;21:89–95. doi: 10.1017/s0952523804041094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry DM, Mitchell R, Standifer KM, du Plessis B. Distribution of plasma membrane-associated syntaxins 1 through 4 indicates distinct trafficking functions in the synaptic layers of the mouse retina. BMC Neurosci. 2006;13:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella SL, Jr, Thoreson WB. Differential modulation of rod and cone calcium currents in tiger salamander retina by D2 dopamine receptors and cAMP. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3537–3548. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardi N, Duvoisin R, Wu G, Sterling P. Localization of mGluR6 to dendrites of ON bipolar cells in primate retina. J Comp Neurol. 2000;423:402–412. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000731)423:3<402::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassle H, Dacey DM, Haun T, Haverkamp S, Grunert U, Boycott BB. The mosaic of horizontal cells in the macaque monkey retina: with a comment on biplexiform ganglion cells. Vis Neurosci. 2000;17:591–608. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800174097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsky L, Jacobowitz DM. Purification, identification and regional localization of a brain-specific calretinin-lie calcium binding protein (protein 10) Novel Calcium-Binding Proteins. 1991a:277–300. [Google Scholar]