Abstract

The present study was an examination of how exposure to print affects sentence processing and memory in older readers. A sample of older adults (N = 139; Mean age = 72) completed a battery of cognitive and linguistic tests and read a series of sentences for recall. Word-by-word reading times were recorded and generalized linear mixed effects models were used to estimate components representing attentional allocation to word-level and textbase-level processes. Older adults with higher levels of print exposure showed greater efficiency in word-level processing and in the immediate instantiation of new concepts, but allocated more time to semantic integration at clause boundaries. While lower levels of working memory were associated with smaller wrap-up effects, individuals with higher levels of print exposure showed a reduced effect of working memory on sentence wrap-up. Importantly, print exposure was not only positively associated with sentence memory, but was also found to buffer the effects of working memory on sentence recall. These findings suggest that the increased efficiency of component reading processes that come with life-long habits of literacy buffer the effects of working memory decline on comprehension and contribute to maintaining skilled reading among older adults.

Keywords: Cognitive Aging, Reading, Print Exposure, Compensation, Sentence Processing, Text Memory

Reading is an important activity for maintaining intellectual capacity and exercising cognitive function across the lifespan (Manly et al., 1999; Manly, Byrd, Touradji, Sanchez & Stern, 2004; Manly, Schupf, Tang, & Stern, 2005; Manly, Touradji, Tang, & Stern, 2003; Stern, 2009), with higher rates of literacy-related behaviors predicting greater levels of memory for text (Rice & Meyer, 1985, 1986; Hartley, 1986), attenuated longitudinal decline in memory more generally (Manly et al., 2005), and resistance to late-life cognitive pathology (Wilson et al., 2000). Sustained literacy habits also cultivate crystallized abilities (Stanovich, West, & Harrison, 1995), such as vocabulary (Verhaghen, 2003) and general world knowledge (Ackerman, 2008) that can be well preserved into very late in life, and to some extent offset declines in processing capacity (Meyer & Rice, 1989). However, less is known about how the accumulated experience of reading contributes to the capacity to learn from text or the moment-to-moment processes underlying text comprehension, the fluent experience of which would likely contribute to continued reading (cf. Payne, Jackson, Noh, & Stine-Morrow, 2011). In the current study, we investigated whether individual differences in exposure to print, a measure of reading-related engagement, contributes to sentence processing and memory among older readers.

Reading and Aging

The mechanisms underlying the comprehension of written language are complex, involving the active processing and integration of information as the reader controls pacing through the text. At the word level, readers encode orthographic and lexical information. At the sentence level, readers parse sentences into syntactic constituents (Pickering & van Gompel, 2006) and construct a semantic representation of the integrated ideas given by the text (Kintsch & Keenan, 1973; McKoon & Ratcliff, 1980; 2008). This textbase representation of the sentence is resilient relative to the surface form and is the basis for text memory (Kintsch, Welsch, Schmalhofer, & Zimny, 1990). One method that has been used by researchers to measure the moment-to-moment allocation of attention to word and textbase processes is the resource allocation approach (Aaronson & Scarborough, 1977; Just & Carpenter, 1980; Lorch & Myers, 1990; Millis, Simon, & tenBroek, 1998; Schroeder, in press). This approach involves recording millisecond reading times (in a word-by-word or segment-by-segment self-paced paradigm or with eye-tracking) and using statistical techniques (e.g., random regression or mixed effects modeling) to decompose these reading times into process-specific components. For example, when a random regression approach (Lorch & Meyers, 1990) is used to model how individuals’ reading time is affected by particular linguistic features, the resulting coefficients represent each individual’s attentional allocation policy in engaging the text demands online.

A number of studies have used this approach to examine age differences in reading strategies during sentence and text processing (e.g., Stine-Morrow, Miller et al., 2001; Stine-Morrow et al., 2008). Collectively, these studies have found that age differences in text memory can be explained to some extent by a reduced allocation of attentional resources to textbase processing during reading. However, older readers appear to be able to achieve relatively high levels of performance, in part by allocating disproportionately more time to textbase processes, such as conceptual integration (see Stine-Morrow, Miller, & Hertzog, 2006; Stine-Morrow & Miller, 2009, for reviews).

A hallmark of language comprehension is the ability to construct a coherent representation in memory of the conceptual relationships given by a text (Kintsch et al., 1990; Kintsch, 1998). There is substantial evidence suggesting that elaborated semantic and conceptual analysis occurs at clause and sentence boundaries (i.e., across input cycles; see Kintsch, 1998). This phenomenon is called wrap-up and is characterized by peaks in reading time at clause and sentence boundaries (Just & Carpenter, 1980; Rayner et al., 1989, 2000). Wrap-up effects have been found to be one particular textbase process associated with higher levels of memory performance among older adults (Stine, 1990; Stine-Morrow et al., 2008; Stine-Morrow, Miller, et al., 2001), suggesting that greater attention to conceptual integration during reading serves an essential compensatory function in engendering high levels of comprehension with advancing age.

Print Exposure, Verbal Efficiency, and Language Processing

Even within literate populations, there is a great deal of variability in how much people read in everyday life. Stanovich and colleagues (Stanovich & Cunningham, 1992; Stanovich & West, 1989) have coined the term print exposure to describe the habitual investment in reading and literacy activities. The Author Recognition Test (ART; Stanovich & West, 1989) was developed as a performance-based measure of print exposure that avoids common issues with self-report data (Stanovich & West, 1989; Paulhus, 1984). In the ART, participants are given a checklist containing authors and foils and are asked to indicate which names they recognize as authors. An overall discriminability score is calculated to adjust for false alarms. The logic of this measure is that people who read widely develop a familiarly with the names of authors even if they haven’t read their work. Across multiple studies, both the reliability and construct validity of the ART have been established (Acheson, Wells, & MacDonald, 2008; Cunningham & Stanovich, 1992; Stanovich & West, 1989; Stanovich, West, & Harrison, 1995; West, Stanovich, & Mitchell, 1993), with scores on the ART relating highly to both subjective (e.g., activity preference, self-reported time) and objective (e.g., observed reading in natural environments) measures of reading habits.

Researchers have long been interested in the role that print exposure plays in vocabulary development, cognitive ability, and word-identification processes in children and young adult readers (Cunningham & Stanovich, 2003; see Long, Johns, & Morris, 2006). In developing readers, for example, higher levels of print exposure (as measured by the ART) uniquely predict facilitation in visual word recognition (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1990). Interestingly, the impact of print exposure on word recognition processes is maintained into college age, suggesting that individual differences in print exposure still affect orthographic and lexical processing even among young adult readers, long after they have developed into skilled readers (Stanovich & West, 1989; Unsworth & Pexman, 2003; Chateau & Jared, 2000). These effects are maintained even when accounting for general vocabulary ability (Chateau & Jared, 2000), suggesting that print exposure contributes to word recognition processes over and above reading-related gains in vocabulary.

According to verbal efficiency theory (Perfetti, 1985, 2007), this increased efficiency in the retrieval of orthographic and lexical codes that comes with accumulated reading experience may free up resources to be available for higher-level language processes. For instance, Ruthruff and colleagues (2008) found that visual word recognition shows evidence of increased automaticity among more highly skilled readers. A similar effect is also found among older adults, who were assumed to have greater cumulative experience in lexical processing than younger readers (Lien et al., 2006). It is important to note that this age-related benefit in visual word recognition would be expected only for older readers with relatively stronger literacy habits. That is, automaticity in lexical processing would not be assumed to come “for free” with age. Rather, there is a great deal of individual variability in lexical efficiency among older adults that may, in part, be explained by individual differences in exposure to print.

There is also evidence that efficient word-level processing leads to the greater availability of resources for more elaborative semantic processing. Gao and colleagues (2011) found evidence for this word-level/textbase-level tradeoff predicted by verbal efficiency theory. They presented text in varying levels of visual noise in order to manipulate the difficulty of word-level encoding and found that when visual noise was high, participants allocated more time to word-level processing (i.e., greater time spent at less frequent and longer words), but this came at the cost of reduced attentional allocation to textbase processes and poorer memory for text.

Collectively, these studies suggest that greater experience with skilled reading may result in more efficient lexical processing that may, in turn, free up resources for more demanding textbase processing. Given the cognitive profile of older adults, who typically have reduced cognitive capacity but at the same time incur the benefits of an accumulated lifetime of reading experience, individual differences in exposure to print would be expected to play an important role in sentence processing and memory within this group of readers.

A distinct but related possibility is that an increased efficiency in lexical processing would serve a compensatory function in sentence processing and memory particularly for older adults with diminished cognitive abilities. Age-related deficits in verbal working memory (vWM) are robust (Bopp & Verhaghen, 2005) and have been argued to be an important mechanism responsible for declines in sentence and text comprehension (Borella, Ghisletta, de Ribaupierre, 2011; Daneman & Merikle, 1996; Just & Carpenter, 1992; Just, Carpenter, & Keller, 1996). While the empirical evidence for effects of vWM on online language processing are mixed (Caplan & Waters, 1999; Caplan et al., 2011; Gordon, Hendrick, & Johnson, 2001; Fedorenko et al., 2006; Just & Carpenter, 1992; Kemper et al. 2004; Kemper & Liu, 2007; MacDonald & Christiansen, 2002; Stine-Morrow, Ryan, & Leonard, 2000; Waters & Caplan, 1996; 2001; 2005), there is a great deal of evidence that vWM impacts sentence memory and reading comprehension (Daneman & Merikle, 1996; DeDe et al., 2004; Friedman & Miyake, 2004, Waters & Caplan, 2005; Stine-Morrow et al., 2008).

At the same time, certain factors have been shown to buffer the impact of vWM on text processing and memory among older readers. For example, if older adults have sufficient prior contextual knowledge of the information to be read, they show greater efficiency during reading and minimal effects of vWM on recall, suggesting that readers can use domain knowledge to buffer against capacity declines during reading (Miller, Cohen, & Wingfield, 2006; Miller, 2009). In a similar vein, it may be that increased practice with reading serves to alleviate the impact of capacity limitations on text processing and memory for text. To the extent that individual differences in print exposure reflect differences in the practice of a highly skilled activity that continues to accrue benefits over time (cf. Ericsson et al., 2006), then engagement in reading-related activities may have beneficial effects on text processing and memory, even among older adults with reduced cognitive capacity.

The Current Study

The current study addressed two particular mechanisms through which individual differences in print exposure might impact sentence processing and memory performance among older readers. First, to the extent that greater print exposure leads to facilitated orthographic and lexical processing that frees up resources for semantic integration, we hypothesized that those with higher levels of print exposure would be facilitated in word-level processing during reading, but would show increased allocation to higher-level textbase processing and improved sentence memory. We call this the efficiency hypothesis. Second, although individual differences in vWM have been shown to impact sentence comprehension, it is not known how print exposure and vWM jointly determine text processing and recall. Thus, we examined the moderating effect that print exposure has on sentence processing and memory among older adults with varying levels of verbal working memory. We reasoned that higher levels of print exposure might operate as a compensatory “reserve” mechanism by buffering against the impact of capacity limitations on sentence processing and memory. Specifically, any effects of vWM on textbase processing and sentence recall should be diminished among individuals with greater exposure to print. We call this the reserve hypothesis.

Method

Participants

Participants were 139 community-dwelling older adults. These data are reported from the Senior Odyssey project (Stine-Morrow et al., 2007; Stine-Morrow et al., 2008), an ongoing community-based field experiment investigating the effects of intellectual engagement on cognition, and are based on pretest measures, before participants were randomly assigned to an experimental or control group. Participants ranged in age from 64 to 92 years (mean = 72.03, SD = 7.94), and had an average of 15.41 years of education (SD = 2.67). The participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were screened for incident dementia or other major cognitive impairment, such that all participants in the sample scored above a 23 on the Mini-Mental State Exam (Folstein, Folstien, & McHugh, 1975).

Measures

Print Exposure

Print exposure was measured with the ART (Stanovich & West, 1989), as described earlier. Participants were instructed to select the authors they knew and were discouraged from guessing. A discriminability score was calculated as hits minus false alarms. In this sample, the ART was highly correlated with each of the major variables of interest in the current study (see Table 2), as well as with a number of other key variables that were collected, confirming the validity of the ART in this sample. ART scores were correlated with a self-report of the number of hours per week spent reading books, r = .42, p < .001, and with performance on the comprehension subtest of the Nelson-Denny Reading Test, a timed measure of general reading comprehension, r = .26, p > .001. Additionally, the ART was positively associated measures of psychomotor speed (letter and pattern comparison tasks, Salthouse & Babcock, 1991; and the identical pictures test, Ekstrom, French & Harman, 1976; α = .84), r = .23, p > .001, and reasoning (letter sets, number series, letter series, word series tasks, Ekstrom et al., 1976; and the everyday problem solving task; Marsiske & Willis, 1995; α = .90), r = .20, p > .01, which is in line with prior research finding positive relationships between reasoning, fluid cognition, and print exposure (Stanovich & West, 1995; Siddiqui, West, & Stanovich, 1998).

Table 2.

Estimates and Standard Errors From Linear Mixed Effects Models of Reading Time

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | Est | SE | Est | SE | Est | SE | Est | SE | ||

| Intercept | 6.493*** | .039 | 6.764*** | .066 | 6.691*** | .317 | 6.736*** | .317 | 7.142*** | .432 | |

| Fixed Item Effects | |||||||||||

| Syll | .049*** | .01 | .068*** | .011 | .066*** | .012 | .062*** | .015 | .117*** | .033 | |

| logWF | −.051*** | .001 | −.058*** | .007 | −.057*** | .007 | −.054*** | .009 | −.047** | .019 | |

| NC | .058*** | .017 | .084*** | .020 | .086*** | .020 | .071* | .028 | .123* | .061 | |

| IntSB | .040** | .015 | .064*** | .019 | .066*** | .019 | .016 | .029 | −.079 | .064 | |

| SB | .479*** | .028 | .458*** | .039 | .454*** | .033 | .258*** | .047 | −.271*** | .099 | |

| Fixed Subject Effects | |||||||||||

| ART | — | — | −.026*** | .005 | −.019** | .007 | −.019** | .007 | −.055* | .028 | |

| Age | — | — | — | — | .001 | .004 | .001 | .004 | .001 | .004 | |

| Vocab | — | — | — | — | −.046 | .038 | −.047 | .037 | −.046 | .037 | |

| vWM | — | — | — | — | −.028 | .029 | −.038 | .030 | −.134 | .077 | |

| vWM×ART | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .009 | .006 | |

| Two-Way Cross-Level Interactions | |||||||||||

| ART×Syll | — | — | −.002*** | .001 | −.002*** | .001 | −.002** | .001 | −.007* | .003 | |

| ART×logWF | — | — | .001* | .000 | .001 | .000 | .001 | .000 | .000 | .002 | |

| ART×NC | — | — | −.002** | .001 | −.002** | .001 | −.003** | .001 | −.008 | .005 | |

| ART×IntSB | — | — | .002* | .001 | .002* | .001 | .003* | .001 | .003 | .005 | |

| ART×SB | — | — | .003 | .002 | .002 | .002 | .000 | .002 | .050*** | .008 | |

| vWM×Syll | — | — | — | — | — | — | .001 | .003 | −.012 | .008 | |

| vWM×logWF | — | — | — | — | — | — | −.001 | .002 | −.002 | .004 | |

| vWM×NC | — | — | — | — | — | — | .004 | .006 | −.009 | .014 | |

| vWM×IntSB | — | — | — | — | — | — | .023*** | .006 | .038* | .015 | |

| vWM×SB | — | — | — | — | — | — | .055*** | .009 | .185*** | .023 | |

| Three-Way Cross-Level Interactions | |||||||||||

| ART×vWM×Syll | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .001 | .001 | |

| ART×vWM×logWF | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .000 | .000 | |

| ART×vWM×NC | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .001 | .001 | |

| ART×vWM×IntSB | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | −.001 | .001 | |

| ART×vWM×SB | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | −.012*** | .002 | |

| Random Effects | |||||||||||

| τ2 | .122*** | .015 | .091*** | .011 | .089*** | .011 | .089*** | .011 | .087*** | .011 | |

| Ψ2 | .014*** | .001 | .014*** | .001 | .014*** | .001 | .014*** | .001 | .014*** | .001 | |

| σ2 | .167*** | .001 | .169*** | .001 | .168*** | .001 | .165*** | .001 | .169*** | .001 | |

| Model Fit (−2 Log Likelihood) | 64428.51 | 63063.12 | 57969.68 | 57851.11 | 57795.82 | ||||||

Vocabulary

The advanced vocabulary and extended range vocabulary tests from the Educational Testing Service Kit of Factor Referenced Cognitive Tests (Ekstrom, French & Harman, 1976) were used to measure vocabulary. Both tests are timed and similar in that, for each item, participants are asked to choose a correct synonym of a target word from a list of five possible words. Because of the high correlation between these two measures (r = .82, p < .001), they were combined into one composite measure of vocabulary for each subject. This composite showed high rank-order stability, with a test-retest reliability correlation of .78 (p > .001).

Verbal Working Memory (vWM)

The loaded reading span task, as described in Stine and Hindman (1994), was used to measure verbal working memory. Participants read a set of sentences silently and were asked to immediately make true/false judgments after each sentence. After reading all of the sentences in a group, the participants were asked to recall all of the target words (the last words of each sentence in that group) in order. The number of sentences per set increased with progress through the task (until eight sentences per set or when the participant could no longer recall each of the target words in a set successfully). The participants’ final score was the number of target words recalled within the highest set in which they did not make an error, plus a fraction for the number of correctly recalled words on the set in which they erred. This measure showed modest test-retest reliability in this sample, r = .40, p < .001.

Sentence Materials

Each participant read a set of 24 sentences adapted from the stimuli in Stine-Morrow, Milinder et al. (2001). Each sentence contained 18 words and was followed by a filler sentence to ensure that retrieval planning did not contaminate reading times on the sentence-final word. These filler sentences were not analyzed. This resulted in 18 × 24 = 432 total words read per subject. Each of these words was coded for a set of five variables reflecting resource allocation to text processing demands. Word-level variables included: (1) the number of syllables (Syll) and (2) the natural logarithm of word-frequency (lnWF), using norms from Francis and Kucera (1982). These two variables reflect time spent on orthographic decoding and lexical access, respectively. Textbase level variables included: (3) whether a word introduced a new concept in the sentence (NC), (4) whether the word marked the end of a clause or other minor syntactic boundary (IntSB), and (5) whether the word occurred at a sentence boundary (SB). Readers spend more time on words that introduce new concepts (Haberlandt, Graesser, & Schneider, 1986) and readers allocate more time to processing words at the end of clause and sentence boundaries (i.e., wrap-up). These variables have consistently been shown to affect reading times (see Stine-Morrow, Milinder et al., 2001; Stine-Morrow et al., 2008) for both younger and older readers. In the analyses reported in this study, the number of syllables and word frequency were treated as continuous predictors and the remaining text variables were dummy coded (0/1) for the absence or presence of each effect.

Procedure

Participants completed the battery of measures in the current study as part of a larger group testing session lasting approximately two hours. Participants were later administered the sentence reading task in a larger individual laboratory session also lasting approximately two hours. For the reading task, the two-sentence passages were presented on a 19-in. (48.3 cm) Dell M782 monitor set to a resolution of 1024 × 768 pixels, controlled by a Dell 3.20 GHz computer. MATLAB software (Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA) was used to control presentation and record millisecond reading-times.

Participants read each passage word-by-word, using the moving window method (Aaronson & Ferres, 1984). Each sentence began with all punctuation intact, as well as a set of underscores representing each word in the sentence visible to the participant. The initial press of the space bar produced the first word of the sentence. Succeeding space bar presses produced the next word while concurrently removing the prior word. On a fixed but randomly selected one-third of the sentences, an indicator was presented at the close of the sentence instructing the participants to recall aloud what they had just previously read. Oral recall was recorded and transcribed for later scoring.

Analyses

Analyses on the reading time data were performed using generalized linear mixed effects models (GLMM), with subjects and words specified as crossed random effects. The sentence memory data were analyzed with logit mixed-effects models, with subjects and sentences specified as crossed random effects (see Jaeger, 2008). SAS (version 9.2) procedure MIXED was used to fit the reading time models and procedure GLIMMIX was used to fit the sentence memory models1.

Similar to the recent use of mixed effects modeling instead of traditional subject (F1) and item (F2) analyses in experimental psycholinguistic research, the resource allocation (RA) approach is also amenable to mixed effects modeling. In the classic RA approach, within-participant reading times are regressed onto item-level predictors and the resulting regression coefficients are submitted to a separate analysis across subject-level effects (see Lorch & Myers, 1990). Much in the way that GLMM draw strength by being able to combine F1 and F2 analyses, GLMM can also model the subject analyses and item-level regressions in RA simultaneously, resulting in more precise estimates, correct standard errors, and valid statistical tests of effects (see Baayen et al., 2008 for results from a simulation study). Furthermore, it is possible to simultaneously model interactions between predictors of subject and item variance.

The reading time models were based on maximum likelihood estimation and the sentence memory models were based on maximum likelihood estimation through the Laplace approximation. Significance tests for fixed effects were conducted using likelihood ratio tests (Agretsi, 2002; Snijders & Bosker, 1999). This test statistic is calculated as the difference between -2 times the natural logarithm of the likelihood for a full model and a nested model (without the predictor being tested) and follows an approximate χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom (df) equal to the difference in parameters between the full and nested models. For random effects, significance tests are conducted using a likelihood ratio test statistic where the sampling distribution of the test statistic is a mixture of two χ2 distributions, df = 0 and 1 (Self & Liang, 1987; Stram & Lee, 1994; 1995; Verbeke & Molenburghs, 2000).

Results

Table 1 presents the means and standard errors for age, educational level, vWM, vocabulary, and sentence memory, and their intercorrelations.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Errors, and Correlations among Age, Educational Level, Verbal Working Memory, Vocabulary, Print Exposure, and Sentence Memory

| M (SE) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 72.30 (.65) | |||||

| 2. Ed | 15.40 (.22) | .01 | ||||

| 3. vWM | 3.92 (.08) | −.14† | .15† | |||

| 4. Vocab | .00a (.09) | .03 | .49** | .22* | ||

| 5. ART | 10.20 (.43) | −.18* | .30** | .20* | .62** | |

| 6. Recall | .51 (.01) | −.12 | .28** | .34** | .46** | .34** |

Note.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01.

M = Mean; SE = Standard Error; Ed = Educational level; vWM = Verbal Working Memory; Vocab = Composite of Extended Range Vocabulary and Advanced Vocabulary; ART = Author Recognition Test; Recall = Sentence Memory.

Mean is equal to 0 because it is based on a composite of two standardized measures.

Effects of Print Exposure on Online Sentence Processing

There were 60,048 total observations (432 observations per subject × 139 subjects) for the reading time (RT) analyses. The natural logarithm (ln) of RTs was calculated to transform the distribution to normality. These RTs were then trimmed about each individual’s mean, such that RTs over three standard deviations were replaced with the value at the third standard deviation. This constitutes a very conservative trimming procedure, resulting in less than .02% replacement of the data.

Based on the unconditional means model (see Equation 1 in Appendix A), we entered predictors of reading time sequentially in 5 models. First, in Model 1, we examined only the item-level predictors of reading time. It was specified as seen in Equation 2 in Appendix A and represents the fixed effects of the word and textbase characteristics on reading time. All parameters in this model were significant (see Table 2), replicating findings using the random regression resource allocation approach (see Stine-Morrow et al., 2001; 2008). On average, readers allocated significantly more time to words that were more orthographically complex, to words that were lower in word frequency, to the immediate instantiation of new concepts, and to wrap-up at clause and sentence boundaries.

To examine individual differences in resource allocation as a function of PE, we added performance on the ART as a predictor, as well as the cross-level interactions between ART and each of the five item-level predictors (see Equation 3 in Appendix A). In this model, Model 2, the interaction terms represent the degree to which print exposure moderates the effects of each of the item-level predictors of reading time.

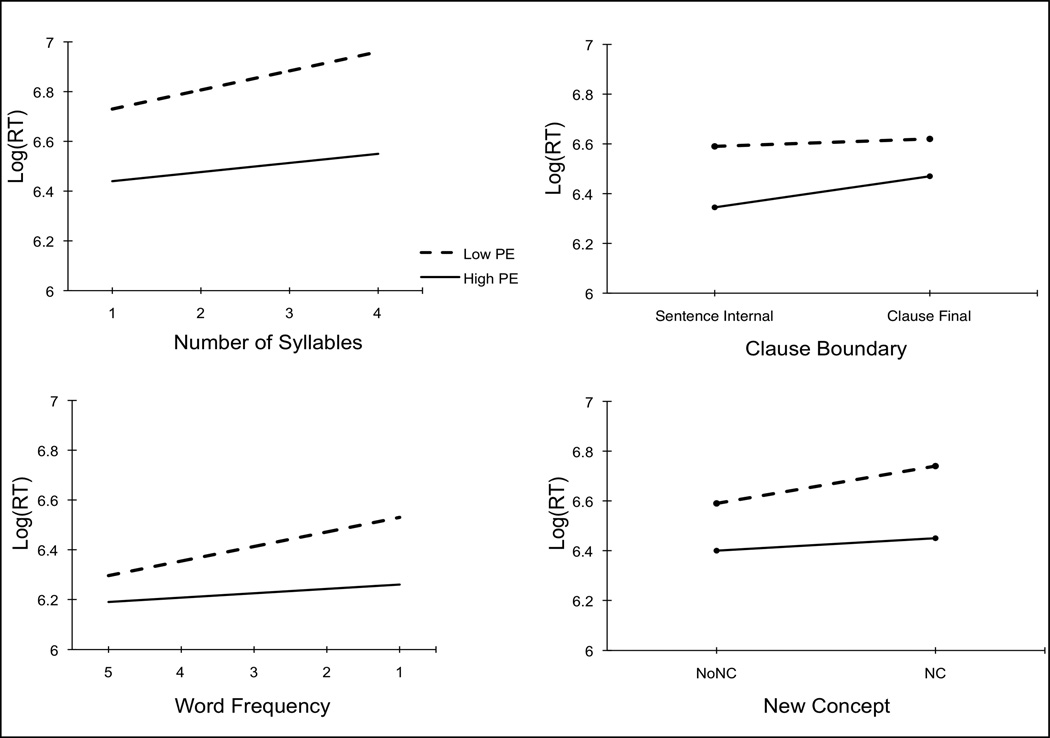

Figure 1 plots the partial effects of each significant interaction parameter in this model at conditional levels of print exposure, where low print exposure is one SD below the mean and high print exposure is 1 SD above the mean. The significant interactions between ART and the text features (Syll, lnWF, NC, and IntSB) revealed that older adults who had greater levels of print exposure were facilitated in orthographic processing, lexical access, and in the immediate instantiation of new concepts, but allocated disproportionally more time to clause wrap-up. While the ART × SB interaction was in the predicted direction, it did not reach significance (p = .20). Collectively, these findings are largely consistent with the verbal efficiency hypothesis (Perfetti, 1985; 2007) in suggesting that those with higher levels of print exposure were more efficient in orthographic decoding and lexical processing, but also showed larger end of clause wrap-up effects, which are associated with demanding semantic integration processes (Rayner et al., 2000; Stine-Morrow et al., 2010; Payne & Stine-Morrow, under review).

Figure 1.

Partial Effects Plots of Significant Interactions in Model 2 at Conditional Levels of Print Exposure (Low Print Exposure = 1 SD Below the Mean; High Print Exposure = 1 SD Above the Mean). Note: PE = Print Exposure; NC = New Concept; Word Frequency is plotted in reverse to show effect from high frequency to low frequency.

In Model 3, we added age, vocabulary, and vWM as covariates in order to assess the unique effects of print exposure after accounting for these individual differences. In our sample, individuals with better vocabulary read more (see also Stanovich & West, 1989), as suggested by the fact that vocabulary was correlated with both print exposure and a self-report of the number of hours per week spent reading books (r = .62; r = .23, respectively), and it is possible that vocabulary performance is a stronger determinant of resource allocation (Stine-Morrow et al., 2008) than print exposure. This raises the possibility that the correlation between print exposure and any online measure of sentence processing might arise because of shared covariance between print exposure and vocabulary (see also, Chateau & Jared, 2000). Likewise, as there exists a moderate correlation between vWM and PE, and vWM often predicts processing time during reading (though not necessarily as a function of processing difficulty; Waters & Caplan, 1999), we also included this as a covariate in the analysis. Examining differences in exposure to print that are independent of vocabulary and vWM constitutes a very conservative test (Chateau & Jared, 2000) because we are partialing out variability in abilities that are likely developed and sustained by greater exposure to print. Thus, the findings we present in Model 3 represent the unique effects of print exposure on online reading comprehension even after it has been “robbed of some of its rightful variance” (p. 265; Cunningham & Stanovich, 1991).

Model 3 was specified by adding the three subject-level covariates to Model 2 (see Appendix A, Equation 4). If age, vocabulary, or verbal working memory were responsible for the relationships between print exposure and resource allocation, then adding these would be expected to reduce or eliminate the significant interactions found in Model 2. After covarying for age, vocabulary, and vWM, all parameters that were significant from Model 2 were largely unchanged in Model 3 (see Table 2), with all parameter estimates remaining relatively stable and significant, with the exception of the ART × lnWF interaction that became marginally significant (p = .07) in Model 3. These findings suggest that the observed effects in Model 2 were largely unique to print exposure and could not be explained by individual differences in age, vocabulary, or vWM.

Next, we report evidence for the reserve hypothesis in online sentence processing, that greater print exposure serves as a compensatory mechanism particularly for individuals with lower cognitive capacity. To test this hypothesis, in Model 4 we examined whether individual differences in vWM affected resource allocation and in Model 5 whether print exposure moderated the effects of vWM on resource allocation.

Model 4 was specified by adding all two-way interactions between vWM and the item-level predictors to Model 3 (see Equation 5 in Appendix A). Table 2 shows that two significant 2-way interactions were found between vWM and the item-level variables. While vWM did not significantly moderate the Syll, logWF, or NC effects, there were reliable interactions between vWM and the clause wrap-up effect (IntSB × vWM) and vWM and the sentence wrap-up effect (SB × vWM). Older adults with higher working memory showed exaggerated clause and sentence wrap-up relative to those with lower working memory, suggesting that working memory afforded processing resources for consolidating and integrating semantic information at syntactic boundaries.

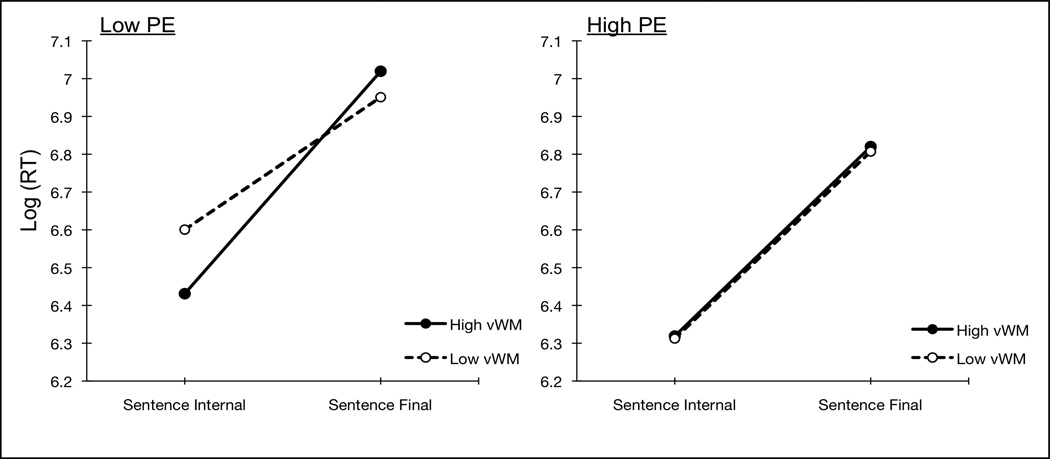

If print exposure contributes to compensation during online sentence processing, then the negative effects of poor working memory on resource allocation should be reduced among individuals with higher scores on the ART. In Model 5, this was tested by adding all 3-way interactions between vWM, ART, and the item-level predictors to Model 4 (see Equation 6 in Appendix A). The findings revealed only some evidence for the reserve hypothesis in online reading times. Of the 3-way interactions of interest that were added in Model 5, the ART × vWM × SB effect was reliable. Figure 2 presents this 3-way interaction, plotting the reading times for sentence internal and sentence final words as a function of print exposure and vWM.

Figure 2.

Partial Effects Plot of the 3-way Interaction in Model 5: Sentence Wrap-up As a Function of Verbal Working Memory (Low = 1 SD Below the Mean; High = 1 SD Above the Mean) and Print Exposure (Low PE = 1 SD Below the Mean; High PE = 1 SD Above the Mean). Note: PE = Print Exposure; vWM = Verbal Working Memory.

To decompose this three-way interaction, test statistics for differences in the simple slopes presented in Figure 2 were calculated (see Aiken & West, 1991; Preacher, Bauer & Curran, 2005; Dawson & Richter, 2006)2. For individuals with lower print exposure (mean − 1 SD), reduced working memory was associated with reduced allocation of time to sentence wrap-up (t = 4.98; p < .001). However, for those with higher levels of print exposure (mean + 1 SD), working memory was not systematically related to sentence wrap-up (t = .02).

These findings are in line with the reserve hypothesis in suggesting that print exposure served to alleviate the influence of working memory capacity on the more cognitively demanding (Payne & Stine-Morrow, under review) sentence wrap-up effect. To the extent that wrap-up represents the time allocated to conceptual integration across sentences (Stine-Morrow et al., 2008, 2010; Just & Carpenter, 1980), these results suggest that print exposure can buffer against the effects of working memory (cf. Miller et al., 2006). That older readers with lower print exposure and lower working memory showed less evidence of wrap-up suggests that they engaged in less end-of-sentence semantic and conceptual integration, which would result in a more fragmented representation of the sentence in memory. This is examined directly in the next section, where we examine the effects of print exposure and working memory on sentence recall3.

Effects of Print Exposure on Sentence Memory

Transcribed recall protocols were scored, using a gist-based criterion, for the proportion of propositions correctly recalled from each of the eight sentences that were probed (Turner & Greene, 1978). Two trained independent raters who were blind to participant characteristics (e.g., age, cognitive scores) assessed a subset of the protocols. Estimates between the two raters showed good inter-rater reliability (r = .93). Based on this procedure, the measure of sentence memory was the number of correct propositions recalled for each sentence by each participant. One participant’s verbal recall protocol was lost due to recording error, so analyses were based on N = 138 participants.

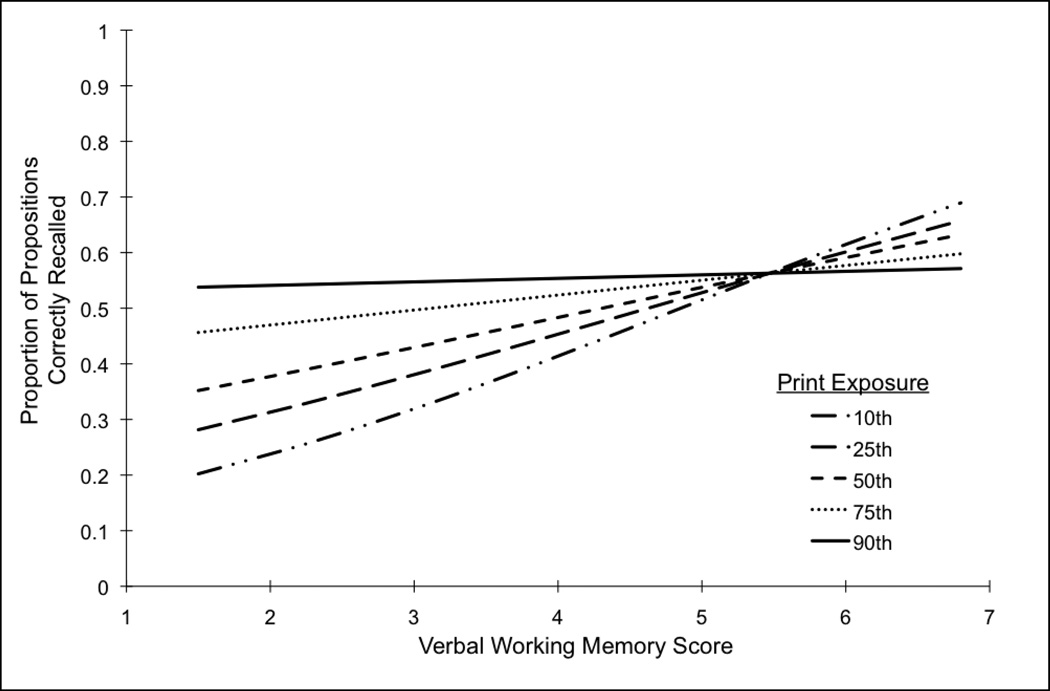

To investigate the effects of print exposure on sentence memory, we first fit a logit mixed-effects model to the data, with subjects and sentences as crossed random effects. This model treats each proposition in each sentence as a trial of a binomial random variable, where remembering a proposition is a success. This model included ART, vWM, and the interaction between vWM and ART as predictors and is presented in Equation 7 in Appendix A.

Both vWM (γ̂10 = .49, SE = .17; χ2(1) = 7.73, p < .001, odds ratio (OR) = 1.63) and ART (γ̂20 = .15, SE = .06; χ2 (1) = 6.02, p < .05; OR = 1.16) emerged as positive predictors of sentence memory. Thus, in line with the efficiency hypothesis, individuals with higher overall scores on the ART showed greater sentence recall. Importantly however, the interaction was also significant (γ̂30 = −.03, SE = .01; χ2 (1) = 4.17, p < .05, OR = .97), suggesting that print exposure moderated the effects of vWM on sentence recall. This interaction is presented in Figure 3, which plots the effect of vWM on the proportion of propositions recalled at varying levels of performance on the ART. Older adults with lower print exposure showed strong effects of vWM on sentence recall, while older adults with higher print exposure showed no systematic relationship between vWM and sentence memory. These results support the reserve hypothesis in suggesting that higher levels of print exposure serve to buffer against the effects of vWM capacity on sentence memory.

Figure 3.

Effects of Verbal Working Memory on Sentence Recall for Older Adults with Varying Levels of Print Exposure (Percentiles of Performance on the ART).

To test the unique effects of print exposure on sentence recall, we fit a model based on the above model that included both age and vocabulary as covariates (see Equation 8 in Appendix A). Unlike the reading time analyses, adding the covariates to the sentence memory models did reduce the effects of ART, leading to a non-significant main effect for ART and a non-significant vWM by ART interaction. Entering the age and vocabulary covariates sequentially revealed that, while age did not impact the main effect of ART nor the vWM × ART effect, adding vocabulary as a covariate did reduce both effects to non-significance. This suggests that the positive effects of print exposure on recall may be due in part to growth in crystallized verbal ability that comes with greater exposure to print4.

Discussion

The findings from the current study suggest that sentence comprehension among older adults may be partially determined by the degree to which they expose themselves to text and habitually engage in skilled reading. Specifically, we found evidence in support of several mechanisms by which print exposure affects reading comprehension. In line with the efficiency hypothesis, we found that higher print exposure was associated with (a) more efficient lexical and orthographic processing, (b) greater allocation of attention to clause wrap-up, and (c) better sentence recall. Importantly, greater print exposure also appeared to act as a compensatory mechanism for individuals with lower working memory capacity, in support of the reserve hypothesis. Specifically, (a) working memory had less of an impact on sentence wrap-up effects for those with higher print exposure and (b) print exposure appeared to buffer against the effects of working memory capacity limitations on sentence recall.

The online reading time findings are consistent with studies demonstrating facilitation in visual word recognition for individuals with higher print exposure (Chateau & Jared, 2000; Stanovich & West, 1989, Sears et al., 2008). Our results extend these findings by examining effects in a population of older readers, as well as in a sentence reading task. By examining effects on sentence processing, we not only showed that higher print exposure is associated with more efficient word-level processing, but also that this efficiency was important in allowing a greater availability of resources to be allocated to more demanding textbase processes, an effect which was particularly valuable for older adults with lower working memory5.

Earlier studies (Rice & Meyer, 1985, 1986; Hartley, 1986) have demonstrated positive relationships between self-reports of reading engagement and text memory among older adults. These early studies suggest that the habitual reading of older adults can be an important and unique contributor to the ability to learn and retain information from text. However, to our knowledge, this effect had not been previously estimated using an objective measure of reading engagement, as was done in the current study. Using this performance-based measure, we presented evidence that higher rates of literacy were associated with resilience in language memory in older adulthood. Importantly, we found that print exposure moderated the relationship between vWM and sentence recall. This suggests that higher rates of print exposure are beneficial to memory for text, especially in the face of capacity declines. Consistent with cognitive reserve theory (Stern, 1999; 2009; Manly et al., 1999; 2004), increased literacy appears to serve as a compensatory mechanism. Cognitive reserve theory is predicated on the view that certain factors (such as education, activity engagement, and literacy) are partially responsible for “individual differences in how tasks are processed that can allow some people to cope better than others with brain changes in general and aging in particular (p. 2027; Stern, 2009). Given that working memory is a basic cognitive ability: (1) that shows normative age-related declines, (2) that subserves complex performance in a number of domains and (3) of which the neural substrates show both structural and functional age-related change (Reuter- Lorenz, et al., 2000), the current study suggests that literacy habits serve as a source of cognitive reserve in buffering against the effects of cognitive decline on language processing and memory for text among older readers.

Interestingly, while the effects of print exposure on online processing appeared to be independent of vocabulary, this was not the case when examining the effects on recall. Adding vocabulary as a covariate reduced the effects of print exposure on recall to non-significance. To the extent that vocabulary performance is an index of general verbal knowledge and crystallized ability (Baltes, 1997; Schaie, 1994), this suggests that increases in crystallized knowledge that come with greater print exposure appear to be an active mechanism contributing to the positive effects on recall. At the same time, greater practice with reading appears to impact the efficiency of online processing over and above its effect on vocabulary (Chateau & Jared, 2000).

Similar to a great deal of the educational and psychological research on literacy, the current study is cross-sectional and correlational, limiting the ability to make causal claims. In fact, as mentioned in the introduction, there likely exists a reciprocal relationship between the cognitive processes underlying text comprehension and rates of print exposure (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1997; Stringer & Stanovich, 2000). However, the development of more sophisticated analyses allows for greater flexibility in making well informed inferences about the effects of reading experience on the component processes of reading (Stanovich & Cunningham, 2003). Thus, while certain limitations exist in terms of experimental manipulation (i.e., one cannot manipulate a lifetime of literacy activities), researchers can still test hypotheses that may not be easily and directly amenable to experimentation. Future research using converging methodologies, designs, and analytical strategies are key to addressing complex questions in the cognitive aging and psycholinguistic literature, such as the effects of literacy on language processing across the lifespan.

Examining the influence of expertise on the efficiency of the cognitive processes that subserve complex performance is an active field of study that cuts across multiple domains (Clancy & Hoyer, 1994; Morrow et al., 2009; Charness, 2009). Consistent with much of this literature on the development of expert performance and deliberate practice (see Ericsson et al., 2006), our results suggest that continued engagement in practicing the highly skilled activity of reading has beneficial effects on sentence processing and memory, even among older adults with reduced processing capacities. Thus, our data are largely in support of the notion that experiential factors, such as engagement in reading-related activities, play a large role in sculpting the cognitive system to perform effectively even in the face of declines.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for support from the National Institute on Aging (Grants R01 AG029475 and R01 AG013935). We also wish to thank Pat Hill and Joshua Jackson for comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Appendix

This appendix contains technical information regarding the generalized linear mixed effects models and general model fitting approach used in the current paper.

Section 1. Reading Time Analyses

The Unconditional Means Model

The unconditional means model (i.e., no predictors) was fit to the data to assess random effects of subject and item variability on reading time; that is,

| (1) |

where: ln(Yijk) is the log transformed reading time for subject j and word k, γ000 is the intercept; U0j0 is the random effect for subject j distributed as N ~ (0, τ2); V00k is word k random effect distributed as ~ (0,ψ2); and the eijk is the residual term that is assumed to be independent and distributed as N ~ (0, σ2). Unsurprisingly, there was significant variability accounted for by both subjects (τ̂2 = .12; SE = .014; χ2 (0/1) > 5,000, p < .001) and words (ψ̂2 = .05, SE = .004, χ2 (0/1) > 5,000, p < .001). The proportion of total variance in reading time accounted for by subjects was 35% and the proportion of total variance in reading time accounted for by words was 15%.

Resource Allocation Model

| (2) |

where: Syll = number of syllables, lnWF = the natural log of word-frequency, NC = whether a word introduced a new concept in the sentence, IntSB = whether the word marked the end of a clause or other minor syntactic boundary, and SB = whether the word occurred at a sentence boundary.

Effects of Print Exposure on Resource Allocation

| (3) |

Where: ART = scores on the author recognition task for print exposure.

Unique Effects of Print Exposure on Resource Allocation

| (4) |

Unique Effects of Print Exposure and Working Memory on Resource Allocation

| (5) |

Where: Vocab = scores on the vocabulary composite and vWM = scores on the reading span task for verbal working memory.

Print Exposure Moderates the Effect of Working Memory on Resource Allocation

| (6) |

Section 2. Sentence Memory Analyses

Effects of Print Exposure and Working Memory on Sentence Recall

| (7) |

where: πjkis the probability of correctly recalling a proposition.

Unique Effects of Print Exposure and Working Memory on Sentence Recall

| (8) |

Footnotes

The use of mixed-effects modeling has been prevalent in social science, education, and behavioral research for some time (Singer, 1998; Snijders & Bosker, 1999). Recently, these modeling techniques have begun to gain ground in psycholinguistic and cognitive psychology research as well (Baayen, Davidson & Bates, 2006; Locker, Hoffman, & Boviard, 2007; Quene & van den Bergh, 2004, 2008; Jaeger, 2008). In conventional psycholinguistic experiments, the use of GLMM incurs several benefits, such as allowing the researcher to analyze fixed and random effects across subjects and items simultaneously, which avoids the need for separate F1 (by-subjects) and F2 (by-items) analyses. Additionally, GLMM are capable of (1) modeling predictors of subject and item level variability simultaneously, (2) modeling both discrete and continuous variables simultaneously, (3) modeling unbalanced designs, and (4) explicitly modeling variances and covariances, allowing for violations of sphericity and homogeneity of error variance (Snijders & Bosker, 1999).

It is important to note that, while these methods for decomposing continuous interactions were originally designed in the context of ordinary least squares regression, these methods are also appropriate and equivalent in the context of GLMM, since we are only probing a parameter from the fixed portion of the model.

Although our analyses focused on verbal working memory as the major indicator of individual differences in processing capacity, similar effects were found for the reading time models when speed of processing was used in place of vWM as a proxy of fluid cognition. That is, re-fitting the reading time models while replacing speed with vWM revealed that processing speed was a significant predictor of reading time (p > .001) and interacted with sentence and clause wrap-up (SB × Speed, p > .001; IntSB × Speed, p > .001). Importantly, the effects of processing speed on sentence wrap-up were buffered by print exposure (ART × SB × Speed, p > .001), much in the same way that the effects of vWM were buffered by greater print exposure. Thus, it appears that individual differences in processing speed acted in a similar fashion to vWM as an indicator of cognitive capacity among older adults.

Unlike the reading time models (see footnote 3), using processing speed in place of vWM revealed that speed did not uniquely predict sentence recall (p = .20) nor was its effect on recall moderated by print exposure (p = .21). The robust effects of processing speed on the reading time models may reflect the fact that psychomotor speed is a stronger predictor of reaction time variables than those based on memory processes. Given that speed did not predict recall, while vWM did (and was influenced by print exposure), this suggests that working memory has broader predictive power for measures of language comprehension, perhaps because complex span measures tap multiple abilities (e.g., executive attention, processing capacity, and resistance to proactive interference; Engle, 2002; Lustig, May, & Hasher, 2001; Whitney, Arnett, Driver, & Budd, 2001) that underlie language comprehension.

Verbal working memory, like most measures of fluid cognition, shows monotonic declines across the entire lifespan. However, within this sample, the correlation between age and vWM was only marginally significant. This is due largely to the restricted age range in the current study (64 – 92). Nevertheless, there was a great deal of variance in vWM among the older adults, suggesting that our older sample showed substantial individual differences in cognitive ability.

Portions of this article were presented at the 63rd annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America.

References

- Aaronson D, Ferres S. The word-by-word reading paradigm: An experimental and theoretical approach. In: Kieras DE, Just MA, editors. New methods in reading comprehension research. Hillsdale, N. J.: Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 31–68. [Google Scholar]

- Aaronson D, Scarborough HS. Performance theories for sentence coding: Some quantitative models. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1977;16:277–303. [Google Scholar]

- Acheson DJ, Wells JB, MacDonald MC. New and updated tests of print exposure and reading abilities in college students. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:278–289. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.1.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman P. Knowledge and cognitive aging. In: Craik FIM, Salthouse TA, editors. The handbook of aging and cognition. 3rd ed. New York: Psychology Press; 2008. pp. 373–443. [Google Scholar]

- Baayen RH, Davidson DJ, Bates DM. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;59:390–412. [Google Scholar]

- Bopp KL, Verhaeghen P. Aging and verbal memory span: A meta-analysis. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2005;60:223–233. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.5.p223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borella E, Ghisletta P, de Ribaupierre A. Age differences in text processing: The role of working memory, inhibition, and processing speed. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2011 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charness N. Skill acquisition in older adults: Psychological mechanisms. In: Czaja SJ, Sharit J, editors. Aging and work: Issues and implications in a changing landscape. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. pp. 232–258. [Google Scholar]

- Chateau C, Jared D. Exposure to print and word recognition processes. Memory & Cognition. 2000;28:143–153. doi: 10.3758/bf03211582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy SM, Hoyer WJ. Age and skill in visual search. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:545–552. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AE, Stanovich KE. Tracking the unique effects of print exposure in children: Associations with vocabulary, general knowledge, and spelling. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1991;83:264–274. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AE, Stanovich KE. Predicting growth in reading ability from children’s exposure to print. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1992;54:74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AE, Stanovich KE. Reading matters: How reading engagement influences cognition. In: Flood J, Lapp D, Squire J, Jensen J, editors. Handbook of research on teaching the English language arts. Second Ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 666–675. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AE, Stanovich KE. Assessing print exposure and orthographic processing skill in children: a quick measure of reading experience. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1990;82:733–774. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AE, Stanovich KE. Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:934–945. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman M, Merikle PM. Working memory and comprehension: A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1996;3:422–433. doi: 10.3758/BF03214546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeDe G, Caplan D, Kemtes K, Gloria W. The relationship between age, verbal working memory, and language comprehension. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:601–616. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom RB, French JW, Harman HH. Manual for the kit of factor-referenced cognitive tests. Princeton: Educational Testing Service; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Engle RW. Working memory capacity as executive attention. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002;11:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson AK, Charness N, Feltovich P, Hoffman RR. Cambridge handbook on expertise and expert performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MR, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practice method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis W, Kucera H. Frequency Analysis of English Usage. New York: Houghton Mifflin; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Geo X, Stine-Morrow EAL, Noh SR, Eskew RT. Visual noise disrupts conceptual integration in reading. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2011 doi: 10.3758/s13423-010-0014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graesser AC. Prose comprehension beyond the word. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Haberlandt K, Graesser AC, Schneider NJ, Kiely J. Effects of task and new arguments on word reading times. Journal of Memory and Language. 1986;25:314–333. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley J. Reader and text variables as determinants of discourse memory in adulthood. Psychology and Aging. 1986;1:150–158. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.1.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley JT, Stojack CC, Mushaney TJ, Annon TAK, Lee DW. Reading speed and prose memory in older and younger adults. Psychology and Aging. 1994;9:216–223. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.9.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger TF. Categorical data analysis: Away from ANOVAs (transformation or not) and towards logit mixed models. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;59:434–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Carpenter PA. A capacity theory of comprehension: Individual differences in working memory. Psychological Review. 1992;98:122–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Carpenter PA, Keller TA. The capacity theory of comprehension: New frontiers of evidence and arguments. Psychological Review. 1996;103:773–780. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.4.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintsch W, Keenan JM. Reading rate and retention as a function of the number of propositions in the base structure of sentences. Cognitive Psychology. 1973;5:257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kintsch W, Welsch D, Schmalhofer F, Zimny S. Sentence memory: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Memory and Language. 1990;29:133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Lien M, Allen PA, Ruthruff E, Grabbe J, McCann RS, Remington RW. Visual word recognition without central attention: Evidence for automaticity with advancing age. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:431–447. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locker L, Hoffman L, Bovaird JA. On the use of multilevel modeling as an alternative to items analysis in psycholinguistic research. Behavior Research Methods. 2007 doi: 10.3758/bf03192962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long DL, Johns CL, Morris PE. Comprehension ability in mature readers. In: Traxler M, Gernsbacher M, editors. Handbook of Psycholinguistics. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2007. pp. 801–834. [Google Scholar]

- Lorch RF, Jr, Myers JL. Regression analyses of repeated measures data in cognitive research: A comparison of three different methods. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1990;16:149–157. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.16.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig C, May CP, Hasher L. Working memory span and the role of proactive interference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2001;130:199–207. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.130.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Sano M, Merchant CA, Small SA, Stern Y. Effect of literacy on neuropsychological test performance in non-demented, education-matched elders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 1999;5:191–202. doi: 10.1017/s135561779953302x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Touradji P, Tang M-X, Stern Y. Literacy and memory decline among ethnically diverse elders. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2003;25:680–690. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.680.14579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Schupf N, Tank MX, Stern Y. Cognitive decline and literacy among ethnically diverse elders. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2005;18:213–217. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKoon G, Ratcliff R. Priming in item recognition: The organization of propositions in memory for text. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior. 1980;19:369–386. [Google Scholar]

- McKoon G, Ratcliff R. Meanings, propositions, and verbs. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2008;15:592–597. doi: 10.3758/PBR.15.3.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer BJF, Rice GE. Prose processing in adulthood: The text, the reader, and the task. In: Poon LW, Rubin DC, Wilson BA, editors. Everyday cognition in adulthood and late life. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. pp. 157–194. [Google Scholar]

- Miller LMS. Age differences in the effects of domain knowledge on reading efficiency. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:63–74. doi: 10.1037/a0014586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LMS, Cohen JA, Wingfield A. Knowledge reduces demands on working memory during reading. Memory & Cognition. 2006;34:1355–1367. doi: 10.3758/bf03193277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LMS, Stine-Morrow EAL. Aging and the effects of knowledge on online reading strategies. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1998;53:223–233. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.p223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow DG, Miller LMS, Ridolfo HE, Magnor C, Fischer UM, Kokayeff NK, et al. Expertise and age differences in pilot decision-making. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2009;16:33–55. doi: 10.1080/13825580802195641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus DL. Two-component models of socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1984;46:598–609. [Google Scholar]

- Payne BR, Jackson JJ, Noh SR, Stine-Morrow EAL. In the zone: Flow state and cognition in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0022359. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne BR, Stine-Morrow EAL. Aging, parafoveal preview, and semantic integration in sentence processing: Testing the cognitive workload of wrap-up. doi: 10.1037/a0026540. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti CA. Reading Ability. New York: Oxford University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti CA. Reading ability: Lexical quality to comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2007;11:357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering MJ, van Gompel RPG. Syntactic parsing. In: Traxler MJ, Gernsbacher M, editors. Handbook of psycholinguistics. 2nd Ed. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 455–503. [Google Scholar]

- Quene H, Van den Bergh H. On multi-level modeling of data from repeated measures designs: A tutorial. Speech Communication. 2004;43:103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Quene H, van den Bergh Examples of mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects and binomial data. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;59:413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Rice GE, Meyer BJF. Reading behavior and prose recall performance of young and older adults with high and average verbal ability. Educational Gerontology. 1985;11:57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rice GE, Meyer BJF. Prose recall: Effects of aging, verbal ability, and reading behavior. Journal of Gerontology. 1986;41:469–480. doi: 10.1093/geronj/41.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthruff E, Allen PA, Lien M-C, Grabbe J. Visual word recognition without central attention: Evidence for greater automaticity with greater reading ability. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2008;15:337–343. doi: 10.3758/pbr.15.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder S. What readers have a do: Effects of student’s verbal ability and reading time components on comprehension with and without text availability. Journal of Educational Psychology. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Singer J. Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and residual growth models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1998;23:323–355. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis. London: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich KE, West RF. Exposure to print and orthographic processing. Reading Research Quarterly. 1989;24:402–433. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich KE, West RL, Harrison MR. Knowledge growth and maintenance across the life span: The role of print exposure. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:811–826. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer R, Stanovich KE. The connection between reaction time and variation in reading ability: Unraveling covariance relationships with cognitive ability and phonological sensitivity. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2000;4:41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2015–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine EAL, Hindman J. Age differences in reading time allocation for propositionally dense sentences. Aging and Cognition. 1994;1:2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow EAL, Millinder L, Pullara P, Herman B. Patterns of resource allocation are reliable among younger and older readers. Psychology and Aging. 2001;16:69–84. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.16.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow EAL, Miller LMS. Aging, self-regulation, and learning from text. Psychology of Learning and Motivation. 2009;51:255–285. [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow EAL, Miller LMS, Gagne DD, Hertzog C. Self- regulated reading in adulthood. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:131–153. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow EAL, Miller LMS, Hertzog C. Aging and self regulated language processing. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:582–606. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.4.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow EAL, Miller LMS, Leno R. Patterns of on-line resource allocation to narrative text by younger and older readers. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2001;8:36–53. [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow EAL, Noh SR, Shake MC. Age differences in the effects of conceptual integration training on resource allocation in sentence processing. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2009;63:1430–1455. doi: 10.1080/17470210903330983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow EAL, Shake MC, Miles JR, Lee K, Gao X, McConkie G. Pay now or pay later: Aging and the role of boundary salience in self-regulation of conceptual integration in sentence processing. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:168–176. doi: 10.1037/a0018127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorton R, Light LL. Language comprehension and production in normal aging. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of psychology and aging. 6th ed. New York: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 262–288. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth SJ, Pexman PM. The impact of reader skill on phonological processing in visual word recognition. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2003;56A:63–81. doi: 10.1080/02724980244000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaghen P. Aging and vocabulary score: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:332–339. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters GS, Caplan D. The relationship between age, processing speed, working memory capacity, and language comprehension. Memory. 2005;13:403–413. doi: 10.1080/09658210344000459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JB, Stanovich KE, Mitchell HR. Reading in the real world and its correlates. Reading Research Quarterly. 1993;28:34–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Gilley DW, Beckett LA, Barnes LL, Evans DA. Premorbid reading activity and patterns of cognitive decline in Alzheimer Disease. Archives of Neurology. 2000;57:1718–1723. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.12.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield A, Stine-Morrow EAL. Language and Speech. In: Craik FIM, Salthouse TA, editors. The handbook of aging and cognition. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 359–416. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney P, Arnett PA, Driver A, Budd D. Measuring central executive functioning: What’s in a reading span? Brain and Cognition. 2001;45:1–14. doi: 10.1006/brcg.2000.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]