Abstract

Background

High fertility and low contraceptive prevalence characterize Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region. In such populations, unmet needs for contraception have a tendency to be high, mainly due to the effect of socio-economic and demographic variables. However, there has not been any study examining the relationship between these variables and unmet need in the region. This study, therefore, identifies the key socio- demographic determinants of unmet need for family planning in the region.

Methods

The study used data from the 2000 and 2005 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Surveys. A total of 2,133 currently married women age 15–49 from the 2000 survey and 1,988 from the 2005 survey were included in the study. Unmet need for spacing, unmet need for limiting and total unmet need were used as dependent variables. Socio- demographic variables (respondent's age, age at marriage, number of living children, sex composition of living children, child mortality experience, place of residence, respondent's and partner's education, religion and work status) were treated as explanatory variables and their relative importance was examined on each of the dependent variables using multinomial and binary logistic regression models.

Results

Unmet need for contraception increased from 35.1% in 2000 to 37.4% in 2005. Unmet need for spacing remained constant at about 25%, while unmet need for limiting increased by 20% between 2000 and 2005. Age, age at marriage, number of living children, place of residence, respondent's education, knowledge of family planning, respondent's work status, being visited by a family planning worker and survey year emerged as significant factors affecting unmet need. On the other hand, number of living children, education, age and age at marriage were the only explanatory variables affecting unmet need for limiting. Number of living children, place of residence, age and age at marriage were also identified as factors affecting total unmet need for contraception.

Conclusion

unmet need for spacing is more prevalent than unmet need for limiting. Women with unmet need for both spacing and limiting are more likely to be living in rural areas, have lower level of education, lower level of knowledge about family planning methods, have no work other than household chores, and have never been visited by a family planning worker. In order to address unmet need for family planning in the region, policy should set mechanisms to enforce the law on minimum age for marriage, improve child survival and increase educational access to females. In addition, the policy should promote awareness creation about family planning in rural areas.

Keywords: Contraceptive use, Family Planning, Fertility, Unmet Need, spacing, limiting

Introduction

The Concept “unmet need” describes the condition of fecund women of reproductive age who do not want to have a child soon or ever but are not using contraception (1). Women with unmet need includes all fecund women who are married or living in union—and thus presumed to be sexually active—who are not using any method of contraception and who either do not want to have any more children (unmet need for limiting births) or want to postpone their next birth for at least two years (unmet need for spacing births) (2). Married pregnant women whose pregnancies are unwanted or mistimed and who became pregnant because they were not using contraception as well as those who recently gave birth but are not yet at risk of becoming pregnant because they are pregnant or amenorrhoeic and their pregnancies were unintended are also considered to have unmet need (2,3,4).

In developing countries, women with unmet need for family planning constitute a significant fraction of all married women of reproductive age. Data from the Demographic and Health Surveys showed that among currently married women, 36.9% in Rwanda and 35% in Senegal had unmet need for family planning during the period 1990-2000 (5, 6). In Ethiopia, nationwide it was 36% in 2000 and 33.8% in 2005 (7, 8).

Studies show that satisfying women's unmet need for family planning reduces the total fertility rate (TFR) by a considerable amount (5, 9, 10, 11). In Ethiopia, meeting the demand for family planning is likely to lead to achieving one of the national population policy objectives, i.e., reducing the total fertility rate (TFR) to 4.0 children per woman in 2015. Moreover, meeting unmet need for family planning would avert unwanted or mistimed pregnancies and thereby reduce unsafe abortion (12, 13). It is also likely to prevent high-risk births (14, 15). Unmet need remains a readily defended rationale for the formulation of population policy and a sensible guide to the design of family planning programs (16). Despite its importance, worldwide not much is known about the determinants of unmet need, mainly because most researches on unmet need to date have concentrated on issues of definition and measurement rather than on exploring the causal factors (17, 18, 19).

In Ethiopia, in particular, very little is known about the correlates of unmet need for family planning. The few studies conducted in the country so far are more of descriptive nature and focused on levels rather than causes (15, 20, 21). Meeting unmet need requires that policy makers and program managers know the characteristics of women with a demonstrated unmet need for family planning, that is, the reasons that some couples do not use contraceptives even when they do not want children and use that information to reduce the health and development consequences of unintended fertility (22). Thus, the main objective of this paper is to identify the key demographic and socio-economic factors affecting unmet need for family planning in Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR) of Ethiopia.

Methods

In this study, we used a sub-set of the data collected in the two rounds of the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Surveys (EDHS), conducted in 2000 and 2005, that of SNNPR. These surveys were designed to provide information on health and demographic indicators for the following domains: Ethiopia as a whole; urban and rural areas of Ethiopia (each as a separate domain); and 11 geographic areas (nine regions and two city administrations).

SNNPR is one of the 9 regional states of Ethiopia located in the southern part of the Country. It borders Kenya to the south, Sudan to the southwest and west, Gambella to the northwest and Oromia to the north and east (23) (Figure 1). The Region has an area of 119,000 square kilometers and accounts for a little over 10% of Ethiopia's total land. With an overall population density of 134 persons per km2, SNNPR is the most densely populated region in Ethiopia (24).

Figure 1.

Map of SNNPR, Ethiopia

Source: www.basics.org/publications/pubs/com (22)

According to the 2007 Population and Housing Census, the region has a total population of 14,929,548, accounting for about 20.2% of the country's population of 73,750,932, of which 90% lived in rural areas (25). Women of reproductive age (15–49) make up close to a quarter (24%) of the total population and children under 15 years account for 47.9%, signifying the potential for accelerated population growth.

Infant mortality was 85 per 1000 live births (10.4% higher than the national average) and under-five mortality was 142 per 1000 live births (15.4% higher than the national average). TFR was 5.6 children per woman in 2005 (about 4% higher than the national average) and contraceptive prevalence was 11.4% (18% lower than the national average) (8).

Data used in this paper were taken from the two consecutive rounds of the EDHS conducted in 2000 and 2005. The EDHS 2000 and 2005, implemented by the Central Statistics Agency (CSA) and ORCMacro, were the two comprehensive and nationally representative population and health surveys ever conducted in Ethiopia. Nationally, the surveys covered 15,365 and 14,070 women aged 15–49 years in 2000 and 2005, respectively. Details of the study design for these surveys can be obtained from CSA and ORC Macro (7, 8). In SNNP, the survey included 3,285 women of reproductive age in 2000 and 2,995 in 2005, of which, 2,133 and 1,988, respectively were married women at the time of the survey.

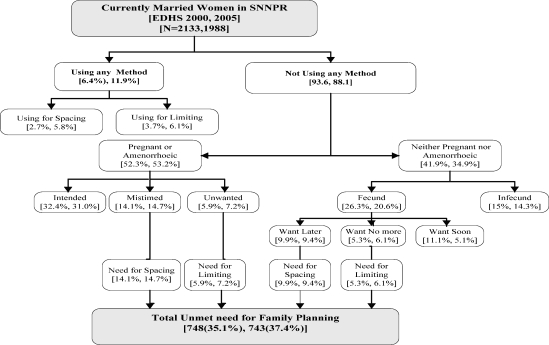

The currently married women were first divided into those using a method (6.4% in 2000, 11.9% in 2005) and those not using a method (93.6%, 88.1%). The nonusers were then divided into pregnant or amenorrheic women (52.3%, 53.2%) and nonusers who were in neither pregnant nor amenorrheic (41.9%, 34.9%) category at the time of the survey. The pregnant or amenorrheic women were then classified by whether the pregnancy or birth was intended (32.4%, 31.0%) at that time, mistimed (14.1%, 14.7%), or not wanted (5.9%, 7.2%). Those in the mistimed or unwanted category were regarded as one component of total unmet need. The other component consists of nonusers who were neither pregnant nor amenorrheic. These women were first divided into fecund (26.3%, 20.6%) or infecund (15%, 14.3%) women, with the fecund women then subdivided by their reproductive preferences. Those who wanted another child soon (11.1%, 5.1%) were excluded from the unmet need estimate, while women who wanted to wait for at least two years (9.9%, 9.4%) or who want no more children (5.3%, 6.1%) were classified in the unmet need category (Figure 2). Thus, the total unmet need in the region was 35.1% in 2000 and 37.4 in 2005 (7, 8).

Figure 2.

Unmet Need among Currently Married women in SNNPR-Ethiopia, EDHS 2000 and 2005.

The multivariate analysis employed two types of models, Multinomial Logistic Regression (Model I) and Binary Logistic Regression model (Model II). Model I was used to identify factors associated with spacing and limiting. It was fitted after classifying the data into three parts (Spacing coded as 1, Limiting coded as 2, and others coded as 0). The others women category which was coded as 0 was considered as a reference (base) category to compare the results with spacers and limiters. Model- II was fitted to identify factors associated with total unmet need for family planning and was fitted after classifying the data into two groups, those with unmet need coded as 1, and those with met need coded as 0).

The two years data were merged by creating a grouping variable year (0=2000 and 1=2005) to conduct the multivariate analysis and the grouping variable ‘year’ was used as predictor to see whether year was determinant factor for unmet need. All tabulations and regression models were estimated using STATA 10.0. In both models, respondent's age, age at marriage, number of living children, Sex composition of living children, child mortality experience, place of residence, respondent's education, partner's education, access to media, employment status, religion and knowledge of at least one modern method of contraception were used as explanatory variables.

Women's age was categorized into three broad groups, 15–24, 25–34 and 35 and above; age at first marriage into two categories, less than 18 and 18 and above; number of living children, into two groups, less than five living children, and five or more living children. Education was grouped into three levels (no education, primary education and secondary and above education) exposure to mass media and work status were categorized into two (no access to media, had access to media, not working and working, respectively). Four categories of religion - Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, Protestant, Muslims and others were used. Family planning factors included in the study are knowledge of contraceptive methods and being visited by a family planning worker.

Results

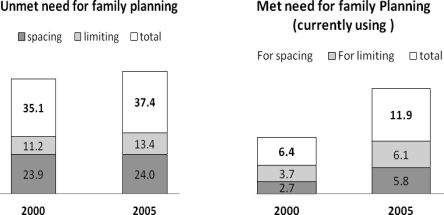

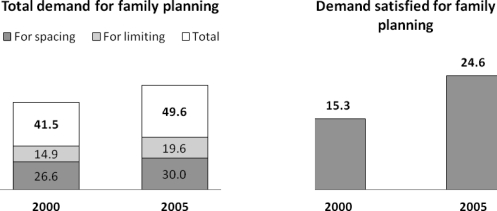

Unmet need increased from 35.1% (23.9 for spacing and 11.2% for limiting) in 2000 to 37.4% in 2005. In 2005, unmet need for spacing remained almost unchanged (24%) but for limiting, it increased by 2.0% to 13.3%. On the other hand, met need for family planning increased from 6.4% in 2000 to 11.9% in 2005. Thus, the total demand for family planning (percent with unmet need plus percent using contraception) in the region was 41.5% in 2000 and 49.3% in 2005. However, only 15.3% was met in 2000 and 24.6% in 2005 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of currently married women with unmet need for family planning and met need for in SNNP, Ethiopia; EDHS 2000–2005

Total Demand for family planning also increased between 2000 and 2005. The “total demand” is the sum of the total unmet need and total current use. It increased from 41.5% to 49.5%; from 26.6% to 30% for spacing; and from 14.9% to 19.6% for limiting births. The percentage of total demand satisfied is calculated by dividing the total current use by the total demand. Even though the satisfaction rate of demand for family planning increased over the survey years, demand for family planning was satisfied for only one women in six in 2000 and one in four in 2005 (Figure 3).

Differentials in Unmet Need for Family Planning

Bi-variate analysis using Pearson's chi-square test revealed that different factors have been significantly affecting unmet need for spacing, unmet need for limiting separately as well as total unmet need. Total unmet need was found to be significantly associated with age at first marriage, number of living children and place of residence in 2005 but with respondent's age only in 2000. On the other hand, unmet need for spacing: age, age at marriage, number of living children, child mortality experience, place of residence, and partner's education were significantly associated factors in both 2000 and 2005. Whereas unmet need for limiting was found to be significantly associated with age, number of living children and child mortality experience both in 2000 and 2005, and sex composition of living children in 2005, and religion in 2000 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Unmet need for family planning, SNNP, Ethiopia, EDHS 2000 and 2005.

| Unmet need for family planning | ||||||||

| 2000 | 2005 | |||||||

| Background Characteristics |

For spacing |

For limiting |

Total | Number of Women |

For spacing |

For limiting |

Total | Number of Women |

| Age | ||||||||

| 15–24 | 38.2 | 3.6 | 41.8 | 466 | 34.9 | 5.8 | 40.7 | 402 |

| 25–34 | 28.5 | 9.3 | 37.8 | 851 | 26.3 | 10.9 | 37.1 | 904 |

| 35+ | 11.0 | 17.4 | 28.4 | 815 | 14.6 | 21.2 | 35.8 | 682 |

| P-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.486 | ||

| Age at Marriage | ||||||||

| <18 | 21.5 | 12.2 | 33.7 | 1,174 | 20.6 | 14.0 | 34.6 | 1,215 |

| 18+ | 26.9 | 9.9 | 36.8 | 958 | 29.5 | 12.3 | 41.8 | 773 |

| P-value | 0.033 | 0.283 | 0.222 | 0.000 | 0.426 | 0.013 | ||

|

Number of living children |

||||||||

| <5 | 28.2 | 6.1 | 34.3 | 1,485 | 27.7 | 7.4 | 35.1 | 1,298 |

| 5+ | 14.3 | 22.8 | 37.0 | 647 | 17.1 | 24.6 | 41.8 | 690 |

| P-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.662 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.018 | ||

|

Sex composition of living children |

||||||||

| Sons > daughters | 24.9 | 11.5 | 36.4 | 777 | 22.8 | 16.6 | 39.4 | 724 |

| Sons=Daughters | 24.1 | 9.4 | 33.5 | 583 | 27.5 | 8.6 | 36.1 | 479 |

| Sons <than daughters | 22.8 | 12.1 | 35.0 | 772 | 23.0 | 13.3 | 36.3 | 785 |

| P-value | 0.760 | 0.448 | 0.280 | 0.008 | 0.548 | |||

|

Child Mortality Experience |

||||||||

| 0 | 30.2 | 8.2 | 38.4 | 1,083 | 26.6 | 10.8 | 37.4 | 1,132 |

| 1+ | 17.5 | 14.2 | 31.7 | 1,049 | 20.6 | 16.8 | 37.4 | 856 |

| P-value | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.034 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.988 | ||

| Place of Residence | ||||||||

| Urban | 17.1 | 13.1 | 30.2 | 147 | 14.0 | 11.5 | 25.6 | 97 |

| Rural | 24.5 | 11.0 | 35.5 | 1,986 | 24.5 | 13.5 | 38.0 | 1,892 |

| P-value | 0.005 | 0.601 | 0.356 | 0.009 | 0.536 | 0.003 | ||

|

Respondent's education |

||||||||

| No education | 23.2 | 10.7 | 33.9 | 1,719 | 22.9 | 14.4 | 37.3 | 1,528 |

| Primary | 24.4 | 15.2 | 39.6 | 308 | 29.5 | 9.6 | 39.2 | 392 |

| Secondary and above | 34.2 | 7.3 | 41.5 | 105 | 17.3 | 11.1 | 28.4 | 69 |

| P-value | 0.176 | 0.138 | 0.199 | 0.037 | 0.119 | 0.331 | ||

| Partner's education | ||||||||

| No education | 18.9 | 11.6 | 30.5 | 1,134 | 20.5 | 14.8 | 35.3 | 926 |

| Primary | 30.1 | 10.7 | 40.8 | 697 | 28.8 | 12.3 | 41.1 | 807 |

| Secondary and above | 28.3 | 11.2 | 39.5 | 287 | 22.0 | 10.7 | 32.7 | 242 |

| Don't know | 37.1 | 0.0 | 37.1 | 15 | 14.2 | 26.6 | 40.9 | 13 |

| P-value | 0.000 | 0.758 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 0.202 | 0.150 | ||

| Religion | ||||||||

| Orthodox | 22.0 | 15.2 | 37.3 | 594 | 22.1 | 12.9 | 35.0 | 422 |

| Protestant | 24.9 | 11.1 | 36.0 | 1,030 | 24.4 | 13.9 | 38.3 | 1117 |

| Muslim | 22.0 | 7.6 | 29.6 | 300 | 23.5 | 12.5 | 36.1 | 281 |

| Other | 27.6 | 4.8 | 32.4 | 208 | 27.4 | 12.5 | 39.9 | 168 |

| P-value | 0.556 | 0.002 | 0.314 | 0.757 | 0.960 | 0.770 | ||

|

Heard of FP in the media |

||||||||

| No | 23.4 | 11.1 | 34.5 | 1,858 | 24.41 | 13.15 | 37.6 | 1,659 |

| Yes | 27.4 | 11.7 | 39.1 | 275 | 22.1 | 14.5 | 36.5 | 329 |

| P-value | 0.242 | 0.811 | 0.210 | 0.429 | 0.580 | 0.777 | ||

| Work Status | ||||||||

| Working | 23.5 | 10.7 | 34.2 | 881 | 24.8 | 13.1 | 37.9 | 1510 |

| Not Working | 24.3 | 11.5 | 35.7 | 1,252 | 21.5 | 14.3 | 35.8 | 478 |

| P-value | 0.745 | 0.640 | 0.556 | 0.226 | 0.5710 | 0.498 | ||

| Total | 23.9 | 11.2 | 35.1 | 2,133 | 24.0 | 13.4 | 37.4 | 1988 |

The association between total unmet need for family planning and respondent's age revealed that total unmet need declined as the age of the respondent increases while unmet need for spacing births declined as the age of respondent increased.

Unmet need for spacing births was 28.5% in 2000 and, 26.3% in 2005 for the younger age cohort (<25) but least for the oldest cohort (11.0% and 14.6%), while unmet need for limiting increased from 3.6% in 2000 and 5.8% in 2005 for the youngest cohort to 17.4% in 2000 and 21.2% in 2005 for the oldest.

The total unmet need for family planning and unmet need for spacing births increased with respondent's age at first marriage. Total unmet need was 33.7% in 2000 and, 34.6% in 2005 among those who married before their eighteen birth anniversary but for those who married at age 18 or later, it was 36.8 in 2000 and 41.8% in 2005. Unmet need for spacing was highest (28.2% in 2000 and, 27.7% in 2005) among women with fewer than five living children but declined for women with five or more living children (14.3% in 2000 and 17.1% in 2005). Yet, unmet need for limiting increased as respondents number of living children increased.’ In both survey years, less than 10% of women with fewer than five living children had unmet need for limiting births, while among women with 5 or more living children, 22.8% in 2000 and, 24.6% in 2005 had unmet need for limiting births.

There appears to be a direct relationship between unmet need for spacing births and education. Both husband's as well as wife's education affect unmet need for spacing births positively. About one in five women (18.9% in 2000 and, 20.5% in 2005) with no education had unmet need for spacing, while 11.6% in 2000 and 14.8% in 2005 had unmet need for limiting. Among women with primary education, 30.1% in 2000 and, 28.8% in 2005 had unmet need for spacing and 10.7% in 2000 and 12.3% in 2005 had unmet need for limiting (Table 1).

Total unmet need for family planning was highest among Orthodox Christians in 2000 and shifted to Protestants in 2005. However, Protestants had highest unmet need for spacing in both survey years. In 2000, unmet need for limiting was highest (15.2%) for Orthodox Christians followed by Protestants (11.1%) and in 2005, this was reversed.

Women who had no access to mass media (radio, television and news paper) had higher level of unmet need for spacing and limiting births compared to those who had exposure to mass media. For instance, among women who had no access to media, 35.8% in 2000 and 38.1% in 2005 had unmet need for family planning. On the other hand, among women with access to media (32.2% and 35.8%, respectively had unmet need for family planning in 2000 and 2005 (Table 1).

Total unmet need for family planning (both spacing and limiting) was found to be higher among women who knew at least one method of family planning compared to those who had no knowledge of any modern contraceptive methods. Close to 40% (37.1% in 2000 and 39% in 2005) of the women who had knowledge of at least one method of family planning were found to have unmet need for family planning. Unmet need for spacing as well as limiting was very high among women who knew at least one contraceptive method (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of currently married women with total with unmet need for family planning by other family planning factors , SNNP Ethiopia, EDHS 2000 and 2005.

| Total demand for family planning | ||||||||

| 2000 | 2005 | |||||||

| Background Characteristics | For spacing |

For limiting |

Total | Number of Women |

For spacing |

For limiting |

Total | Number of Women |

| Knowledge of methods of FP | ||||||||

| Knows no method | 19.1 | 7.7 | 26.81 | 421 | 20.1 | 9.8 | 29.9 | 345 |

| knows at least one method | 25.13 | 12.0 | 37.12 | 1711 | 24.9 | 14.1 | 39.0 | 1643 |

| p-value | 0.052 | 0.082 | 0.009 | 0.166 | 0.059 | 0.014 | ||

| Visited by FP worker | ||||||||

| No | 23.7 | 11.1 | 34.8 | 2,094 | 24.4 | 13.4 | 37.7 | 1,783 |

| Yes | 35.4 | 13.4 | 48.8 | 39 | 21.1 | 13.2 | 34.4 | 205 |

| p-value | 0.281 | 0.700 | 0.352 | 0.402 | 0.962 | 0.386 | ||

| Access to Media | ||||||||

| No | 22.4 | 11.7 | 34.0 | 1,507 | 24.5 | 14.1 | 38.7 | 1,369 |

| Yes | 27.7 | 9.9 | 37.6 | 626 | 22.9 | 11.7 | 34.5 | 619 |

| p-value | 0.009 | 0.364 | 0.151 | 0.509 | 0.256 | 0.194 | ||

| Total | 23.9 | 11.2 | 35.1 | 2133 | 24.0 | 13.4 | 37.4 | 1,988 |

Table 3 shows that after controlling for several respondents' background characteristics, unmet need for spacing was significantly higher among those who lived in rural areas (the relative risk ratio, RRR=4.8 and P-value=0.00); having other religion (RRR=2.09 and P-Value =0.04) apart from familiar religions (Orthodox, Protestant and Muslim), and those who married at the age of 18 and above (RRR=1.99 and P-value =0.00). On the other hand, unmet need for spacing was significantly lower among women aged 25 and above (RRR<0.6 and p-value<0.05); those with primary or secondary and above educational level status (RRR<0.55 and P-Value=0.01); those who had ever heard about family planning methods through media (RRR=0.62 and P-value=0.02); and those visited by family planning worker (RRR=0.52 and p-value=0.02). Although older women had significantly lower unmet need for spacing, age appears to have no significant effect on unmet need for limiting at all levels.

Table 3.

Adjusted effects of selected variables on unmet need for spacing, limiting and total unmet need among currently married women in SNNPR, EDHS 2000 & 2005.

| Background Characteristics | Spacing | Limiting | Total | |||

| RRR | P-value | RRR | P-value | OR | P-Value | |

| Age | ||||||

| 15–24 R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 25–34 | 0.60 | 0.05 | 1.28 | 0.47 | 0.67 | 0.10 |

| 35+ | 0.32 | 0.00 | 1.58 | 0.26 | 0.54 | 0.06 |

| Age at first Marriage | ||||||

| <18 R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 18+ | 1.99 | 0.00 | 1.42 | 0.10 | 1.77 | 0.00 |

| Number of living children | ||||||

| <5 R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 5+ | 0.65 | 0.07 | 1.81 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.98 |

| Sex composition of living children | ||||||

| Sons > daughters R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Sons=Daughters | 1.47 | 0.06 | 1.31 | 0.29 | 1.42 | 0.07 |

| Sons <than daughters | 1.39 | 0.07 | 1.28 | 0.24 | 1.34 | 0.09 |

| Child mortality experience | ||||||

| 0 R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 1+ | 0.71 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.14 |

| Place of residence | ||||||

| Urban R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Rural | 4.79 | 0.00 | 2.46 | 0.01 | 3.63 | 0.00 |

| Respondent's education | ||||||

| No education R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Primary | 0.54 | 0.01 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.00 |

| Secondary and above | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.00 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Orthodox R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Protestant | 1.47 | 0.15 | 1.24 | 0.39 | 1.38 | 0.20 |

| Muslim | 1.28 | 0.33 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.15 | 0.55 |

| Other | 2.09 | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.93 | 1.62 | 0.17 |

| Knowledge of methods of FP | ||||||

| No R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.62 | 0.02 | 0.64 | 0.07 | 0.64 | 0.02 |

| Work status | ||||||

| Working R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Not Working | 0.71 | 0.06 | 0.76 | 0.17 | 0.73 | 0.07 |

| Visited by FP worker | ||||||

| No R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.52 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.00 |

| Year | ||||||

| 2000R | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 2005 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.00 |

| Number of Cases | 1870 | |||||

Unmet need for limiting was significantly higher among women residing in rural areas (RRR=2.5 and P-value=0.01) and those who had five or more children (RRR=1.81 and p-value =0.01). However, number of living children was less likely to affect unmet need for spacing. Unmet need for limiting was significantly lower among women with child loss experience (RRR<0.53 and p=0.05) as well as among women with primary level and above educational status (RRR<0.6 and P-value< 0.05); and among those who had been visited by family planning worker (RRR=0.48 and p-value=0.00).

Overall, seven variables were found to influence the total unmet need for family planning significantly after holding other explanatory variables constant. Women who live in rural areas were four times more likely (OR=3.63 and p-value= 0.00) to have unmet need for family planning compared to those residing in urban areas. Women with primary level and above education were found to be less likely (OR<0.6 and p-value =0.00) to have unmet need for family planning compared to women with no education. Those who had heard about family planning through media were also found to be significantly less likely to experience unmet need for family planning (OR=0.64 and p-value=0.02). Number of living children, religion and child mortality experience were found to have no significant effect on overall unmet need for family planning (Table 3).

Year of the survey was also found to be one of the factors which significantly affected all types of unmet need for family planning. The level of unmet need for family planning significantly declined between 2000 and 2005. In 2005 women were significantly less likely to have unmet need for spacing (RRR=0.39 and p-value=0.000); unmet need for limiting (RRR=0.48 and p-value =0.00) as well as overall unmet need for family planning (OR=0.42 and p-value =0.00) when compared to 2000.

Discussion

This study revealed that 35% of currently married women of reproductive age in SNNPR at the time of the survey had unmet need for family planning in 2000 and this has slightly increased to 37.4% in 2005. In both survey years, the higher proportion of the unmet need was for spacing (23.9 % in 2000 and 24.0% in 2005). The proportion of currently married women with met need (i.e., user of contraception at the time of the survey) for spacing increased by more than two fold (from 2.7% to 5.8%) between 2000 and 2005, while those with met need for limiting increased by 65% (from 3.7% to 6.1%) during the same period. Similar findings have been observed in sub-Saharan African countries. For instance, in West Africa, unmet need ranged from 16 to 34 percent and in Eastern and Southern Africa, it ranged from 13 to 38 percent (30). It was also observed that in SNNP, unmet need for spacing births contributed about two-third of the total unmet need for family planning (68% in 2000 and 64% in 2005).

Respondents' demographic and socioeconomic characteristics were found to influence unmet need for family planning whereas age of respondent, age at marriage, number of living children, child death experience, rural-urban residence, respondent's and partner's education, religion and knowledge of family planning methods were found to have significant effect on unmet need for family planning. These findings are consistent with findings in other studies (21, 27, 28, 29).

In both survey years, unmet need for spacing was inversely related with respondent's age and number of living children and positively related with age at first marriage. On the other hand, unmet need for limiting varied inversely with respondent's age and age at first marriage. This is because younger women are less likely to have achieved their fertility goals and therefore, want to space than limit the number of births, while older women are more likely to have achieved their desired family size and want to stop child bearing. women who got married at the age of 18 or older had slightly higher level of unmet need for spacing births than those who got married before they were 18.

This is because women who got married at the age of 18 or older are likely to adopt ideas about birth limitations more readily compared to those who got married before the age of 18. Hogan, et .al also indicated that women who were 18 years or older at marriage were more likely to discuss family size with their husbands and were also more likely to find out about a method of contraceptive than their younger counterparts (31). Women with higher number of living children (5 or more) are significantly more likely to have unmet need for limiting births than women with less than five living children. A study in Uganda found that women who have five or more living children were over three times likely to have unmet need (OR: 3.37, 95% Cl: 2.72–4.18) than women with less than five living children (26). It appears that women with less than five living children do not wish to stop childbearing due to fear of child death.

SNNP is characterized by high infant and child mortality. In 2005, infant mortality was 85 and under five mortality was 142 per 1000 (8). However, when women have five or more living children, they appear to feel secured of child mortality and wish to stop childbearing.

Women with at least one child loss experience had significantly lower unmet need for spacing and limiting compared to those with no child loss experience. Women with at least one child loss experience either want to replace the dead child immediately or want to continue to procreate as an insurance mechanism against future death of their children (27, 28, 29).

Women residing in rural areas were significantly more likely to be affected by all types of unmet need for family planning (spacing, limiting and total unmet need) (OR=4.79, 2.46 and 3.63, respectively). Studies in other sub-Saharan African countries also showed that rural women had significantly higher unmet need compared to urban women (21, 26, 27, 31). For instance, taking the most recent demographic and health surveys, urban-rural disparity in the following sub-Saharan African countries was observed: Kenya (17%, 27%); Lesotho (20%, 34%); Tanzania (17%, 24%); Uganda (23%, 36%) and Malawi (23%, 29%), respectively (30). The implication of these comparisons, with few exceptions, is that the percentage of total demand for contraception that is satisfied is greater—or at least as higher—in urban than in rural communities. Taking into account the demand satisfaction rate, the explanation for these urban-rural differences no doubt includes the easier accessibility of family planning services in cities, the desire for more children in rural areas, and the greater education in urban areas.

In most populations, women's education is an important determinant of unmet need for family planning and this has been found to be true in SNNPR where women with no education had significantly higher level of unmet need compared with those who had some level of education. In addition, unmet need progressively declined with increasing level of women's education. Hogan, et al also showed that literacy was the most important factor in increasing contraceptive knowledge and the desire to limit or space births (31). Studies elsewhere in Africa also document that unmet is lower for women with better education. For instance in Uganda, unmet need was lower for women with secondary or higher education (26) and in Kenya, women with primary incomplete education were 2 times more likely to experience unmet need for family planning compared to those with primary complete or higher education (27). The possible explanation for this could be that women empowered through education have better access to health facilities and information about modern contraceptive methods than uneducated women.

In conclusion, unmet need for family planning in SNNPR is one of the highest in the country, with a little over one third of currently married fecund women having unmet need for contraception. Therefore, interventions aimed at reducing unmet need should be targeted towards rural women and women with no or little education. Moreover, access to education, increased job opportunities and increased family planning practice will lead to a lower level of unmet need. Other areas of intervention include enforcing the law on minimum age for marriage and reducing infant as well childhood mortality. Moreover, providing all women with full access to family planning services would be instrumental in reducing unmet need.

Figure 4.

Percentage of currently married women with total demand and demand satisfied for family planning in SNNP, Ethiopia; EDHS 2000–2005.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank CSA and ORC Macro for allowing us to use the EDHS 2000 and 2005 Data. We are also thankful to the Institute of Population Studies, Addis Ababa University and the Ethiopian Public Health Association for providing the necessary resources for undertaking this study.

References

- 1.Concepcion M B. Family Formation and Contraception in Selected Developing Countries: Policy Implications of WFS Findings' In Proceedings of the World Fertility Survey Conference, London, 1980; International Statistical Institute; Voorburg, Netherlands. 1980. pp. 197–284. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westoff CF. The potential demand for family planning: A new measure of unmet need and estimates for five Latin American countries. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1988;14(2):45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westoff CF, Bankolle A. The Potential Demographic Significance of unmet need. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1996;22(1):16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westoff CF, Ochoa LH. Unmet need and the demand for family planning. DHS Comparative Studies No. 5. Columbia, Maryland, USA: Institute for Resource Development; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westoff CF, Bankole A. Unmet need: 1990–1994. DHS Comparative Studies No. 16. Calverton, Maryland: Macro International; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.USAID, author. Perspectives on unmet need for family planning in West Africa, Benin; Policy Project Briefing Paper presented at a Conference on Repositioning Family Planning in West Africa; February 15–18, 2005; Accra, Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Central Statistical Authority (CSA) and ORC Macro, author. Ethiopia: Demographic and Health Survey, 2000. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton MD., USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Central Statistical Agency (CSA) and ORC Macro, author. Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton MD., USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westoff CF. Unmet Need at the end of the Century. DHS Comparative Report No. 1. Calverton, MD., USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casterline JB. New Directions in the Philippines Family Planning Program, report No. 9579-PH. Washington DC: World Bank; 1995. “Integrating health risk considerations and fertility preferences in assessing the demand for family planning in the Philippines”. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinding SW, John AR, Rosenfield AG. Seeking common ground: Unmet need and demographic goals. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1994;20(1):23–27. 32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casterline JB, El-Zanatay F, El-Zeini LO. Unmet need and unintended fertility: longitudinal evidence from Upper Egypt. International family planning perspectives. 2003;29(4):158–166. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.29.158.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assefa H, Tekle-Ab M, Misganaw F. Family Planning in Ethiopia. In: Kloos H, Berhane Y, Hailemariam D, editors. The Ecology of Health and Diseases in Ethiopia. 2nd ed. Shama Publishers; 2006. pp. 267–285. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assefa H, Mekonen T. Determinants of infant and early childhood mortality in a small urban community of Ethiopia: a hazard model analysis. Ethiop J Health Dev. 1997;11(3):189–200. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mekonen Y, Ayalew T, Dejene A. A High risk birth, fertility intension and unmet need in Addis Ababa. Ethiop J Health Dev. 1998;12(2):103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casterline JB, Biddlecon E. Factors underlying unmet need for family planning in the Philippines. Studies in Family Planning. 1997;28(3):173–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casterline JB, Sinding SW. Unmet Need for Family Planning in Developing Countries and Implications for Population Policy. Population and Development Review. 2000;26(4):691–723. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon-Muller R, Germain A. Commentary. Stalking the elusive unmet need for family planning. Studies in Family Planning. 1992;23(5):330–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeGraff DS, Silva V. A new perspective on the definition and measurement of unmet need for contraception. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1996;22(4):140–147. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antenane K. Community-based family planning services: A performance assessment of the Jimma FP-CBD project. Ethiop J Health Dev. 1997;11(1):17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antenane K. Attitudes toward Family Planning, and Reasons for Nonuse among Women with Unmet Need for Family Planning in Ethiopia. Calverton, MD, USA: ORC Macro; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.USAID, author. Perspectives on Unmet Need for Family Planning in West Africa: Benin. 2005 POLICY Project Briefing Paper. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Retrieved from http://www.basics.org/publications/pubs/com.

- 24.Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People's Region. Retrieved from http:www.//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SNNPR.

- 25.Central Statistical Agency, author. Population and Housing Census Report at National Level. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Authority; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan EK, Bradley JF, Mishra FV. Unmet Need and the Demand for Family Planning in Uganda. Further Analysis of the Uganda Demographic and Health Surveys, 1995–2006. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wafula S, Ikamari L. Patterns, levels and trends in unmet need for contraception: a case study of Kenya; Paper presented at the Fifth African Population Conference; 10–14 December 2007; Arusha, Tanzania. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalemli-Ozcan A. Stochastic Model of Mortality, Fertility, and Human Capital Investment. Journal of Development Economics. 2003;70(1):103–118. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sah RK. The Effects of Child Mortality Changes on Fertility Choice and Parental Welfare. Journal of Political Economy. 1991;99(3):582–606. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westoff CF. New Estimates of Unmet Need and the Demand for Family Planning. DHS Comparative Reports No. 14. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Macro International Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hogan PD, Betemariam B, Assefa H. Household Organization, Women's Autonomy and Contraceptive Behavior in Southern Ethiopia. Studies in Family Planning. 1999;30(4):302–3148. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.1999.t01-2-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]