Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the visual outcomes, complications and retention of threadless type I Boston keratoprosthesis (KPro) in Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods:

Retrospective analysis of four eyes of four patients (one female and three males; age range: 48 to 72 years) who underwent Boston type I threadless KPro implantation between January and December 2009.

Results:

In the median follow-up of 11 months (range 6 to 14 months), visual outcomes were satisfactory. Preoperative diagnosis included two patients of post-trachoma dense vascularized corneal scarring, one patient of corneal alkali burn and one patient of repeated failed corneal grafts. All patients demonstrated significant improvement in vision; with pre-operative visual acuity of hand movements (HM), counting fingers and HM improved to best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/200, 20/60, 20/50 and 20/30 on their last follow-up visits respectively. None of the patients developed glaucoma as a result of the procedure. No retro-prosthetic membrane developed till the last follow-up visit. One of the four patients had a corneal melt (due to severe dryness associated with trachoma) 6 months after the KPro implantation and underwent a successful KPro revision. Despite the relatively poor prognosis expected in alkali burn eye, the patient attained the maximum BCVA (20/30) of the four eye series on the last follow-up visit at six months.

Conclusion:

In consistent with the earlier reports from other parts of the world, all the 4 eyes had a significant increase in vision after Boston type I KPro implantation. However, patients require close lifelong follow-up to manage any complications.

Keywords: Alkali Burn, Boston Keratoprosthesis, Trachoma

INTRODUCTION

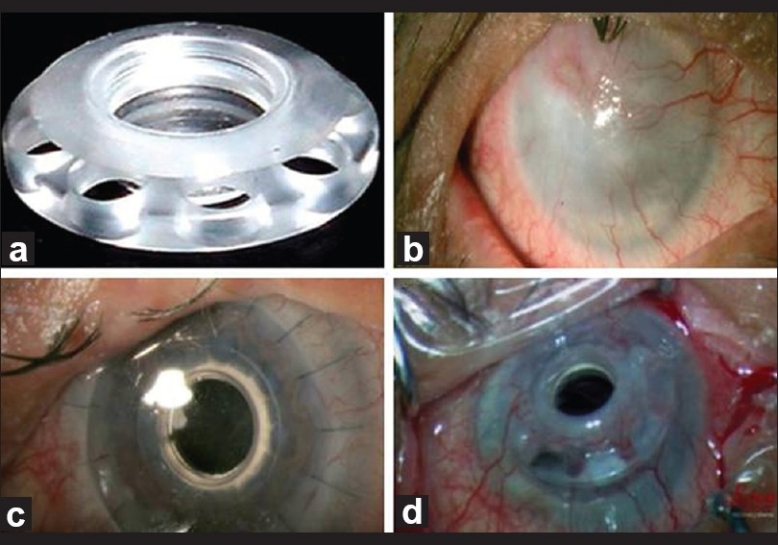

Clinical experience with keratoplasty over the past century has shown that patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP), chemical burns, stem cell deficiencies, and severe vascularization have an extremely poor prognosis.1 In addition, patients with repeated graft failures also have poor likelihood of successful subsequent corneal allo-grafting.2 Keratoprosthesis (KPro) offers an alternative technique to improve vision in such patients. Boston keratoprosthesis (Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA) is the most commonly used keratoprosthesis.3 It is a double-plated PMMA device with a central rigid optic that perforates the cornea. There are 2 variants of the device. Type I, the more common variant [Figure 1a], is a collar button-shaped device with front plate (diameter 5.5–7.0 mm), a central optical stem, and a back plate (available in 8.5 mm diameter adult size and 7.0 mm diameter paediatric size).3–6 The type II KPro is a through-the-lid design with a 2 mm anterior nub designed to penetrate through a tarsorrhaphy and is required to be used in rare indications of extreme dry eyes, symblepharon, and other clinical sequelae associated with the autoimmune and inflammatory disease category that includes SJS and OCP.7

Figure 1.

(a) Type I Boston keratoprosthesis (b) Case 1 with diffuse vascularized corneal scar (secondary to chronic trachoma) (c) One day after implantation of KPro (d): Melted inferior cornea with tilted KPro at 6 months post-operative visit (underwent successful KPro revision)

Our study was designed to evaluate the visual outcomes, complications and retention rates of threadless type I Boston KPro. The snap-on threadless back plate facilitates easier intraoperative assembly and prevents any shredding of endothelium and Descemet's by the posterior plate screwing. To the best of our knowledge, such data has not been reported before in the Middle East.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We undertook a retrospective analysis of 4 eyes of 4 patients (1 female and 3 males; age range: 48 to 72 years) who underwent Boston type I threadless keratoprosthesis implantation at a tertiary care eye hospital in Saudi Arabia by a single surgeon with similar surgical technique. All surgeries, performed between January and December 2009, were considered.

Preoperative assessment included detailed ocular history, including the number of previous surgeries or corneal grafts and examination. Patient's records were examined to ascertain the status of crystalline lens, glaucoma, macular and optic nerve, and best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) when the cornea/ last graft were clear. When possible, visual acuity was recorded using the Snellen's chart; other techniques included counting fingers, hand motions (HM), and central fixation and projection determined with a point light source. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured using Goldmann applanation tonometry or an easy-to-use, portable, handheld instrument (Tono-Pen; Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA), or by digital palpation depending on the status of the corneal disease.

A detailed ocular examination was performed, and when the posterior pole could not be visualized, B-scan ultrasonography was done. All care was taken to ensure that patients chosen for surgery have a fairly optimal visual potential from retinal and optic nerve perspective. Axial length measurements were obtained to decide on the diopteric power of the KPro. The patients and relatives were shown photographs illustrating postoperative cosmetic outcomes and a detailed informed consent was obtained using special KPro consent forms. Outcomes were measured as retention of the device, visual acuity at 1 week, best and last assessed visual acuity and intra-operative and post operative complications.

Surgical technique

Standard surgical technique as described by Dohlman and Barnes was followed.8 Donor cornea in the all the cases was trephined in the periphery with an 8.5 mm corneal trephine (which corresponded to the 8.5 mm size of the KPro backplate) and in the center with a 3 mm dermatological trephine. The optical cylinder of the KPro was passed through it. The back plate of the KPro was then snapped onto the stem with no rotating movement. A titanium locking ring is finally snapped in place behind the back plate to prevent loosening of the back plate. The recipient cornea was trephined using an 8.0 mm corneal trephine (in all the cases) and the graft prosthesis combination was then transferred to the patient's corneal opening and sutured with sixteen 10-0 monofilament nylon interrupted sutures. Both upper and lower puncta were cauterized at the end of the procedure.

Finally, a soft contact lens (Kontur lens; Kontur Kontact Lens Co., Hercules, CA), 16 mm diameter and 9.8 mm base curve, plano power, is placed as a bandage lens and left for indefinite duration (replaced if needed) to prevent dryness and exposure damage to the corneal tissue around the KPro, which might lead to melt and necrosis.5 All patients received lifelong prophylactic antibiotics: gutt moxifloxacin 0.5% (Vigamox, Alcon Inc., Hunenberg, Switzerland), gutt Vacomycin fortified drops (25mg/ml) qid, gutt Prednisolone Acetate 1% (Predforte, Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA, U.S.A.), and Tears Naturale Free (Alcon Inc., Hunenberg, Switzerland).

RESULTS

In the median follow up of 11 months (range six to 14 months), visual outcomes were satisfactory. None of the patients developed glaucoma, retroprosthetic membrane, sterile vitritis or endophthalmitis. One patient underwent KPro revision due to severe dry eye. Details of individual cases are discussed below and relevant details on indication, preparatory and super-added surgical procedures during the device implantation are summarized in Table 1.

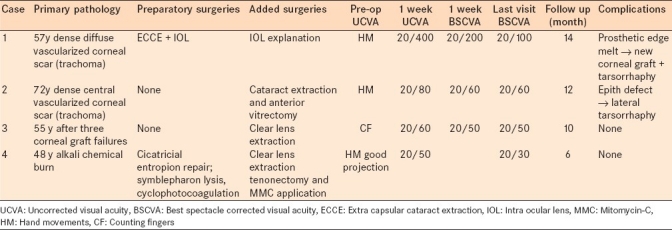

Table 1.

Summary of indications, preparatory and super-added surgical procedures, visual outcomes and complications of individual cases

Case 1

A 57-years-old male presented with uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) of light perception with a very poor projection (secondary to glaucomatous optic atrophy) in his right eye and counting fingers close to face with good projection in his left eye. Slit lamp examination of the left eye showed trichiasis and entropion of upper lid; and diffuse scarring of cornea with 360° deep vascularization reaching the central cornea; left eye IOP was 16 mmHg. Anterior chamber was deep and quiet and the pupil was round, regular and reactive, the posterior chamber IOL was in place (history of left eye cataract surgery 10 years ago). The retinal reflex was poor. Ocular B-scan showed posterior vitreous detachment, flat retina and normal optic nerve head shape. Left eye demonstrated severe dry eye with Schirmer's value (under anesthesia) of 3 mm.

The patient was diagnosed to have severe dry eye with severe corneal scarring and vascularization [Figure 1b] secondary to chronic trachoma. Entropion correction was done and the patient was taken for keratoprosthesis implantation. The decision of IOL explantation as well as threadless aphakic Boston KPro type I implantation in the left eye was made after correction of upper lid entropion.

The day after the surgery [Figure 1c], the UCVA improved to 20/400, IOP was digitally within normal limits; the prosthesis and contact lens were in place. One week after surgery, the patient's condition was stable with UCVA of 20/200 and was discharged on the medications per the protocol.

Six months later, the patient presented to cornea clinic with melted inferior cornea and tilted keratoprosthesis [Figure 1d]. So, the patient was admitted and keratoprosthesis revision was successfully done, in which KPro was dis-assembled, donor melted graft was exchanged with new trephined corneal graft of 8.50 mm then KPro was re-assembled and sutured in place. Generous medial and lateral tarsorrhaphy were done. At the last visit, 14 months after the initial KPro surgery, KPro was stable with UCVA of 20/100.

Case 2

A 72-years-old male presented with post-trachomatous central dense vascularized corneal scar in his right eye. UCVA in his right eye was HM and the IOP was 18 mmHg. Schirmer's test with anesthesia was 5 mm. Slitlamp examination revealed rounded, regular, reactive pupil and nuclear cataract (Grade III). Ocular B scan of the right eye revealed normal shaped posterior segment structures.

Boston KPro type I (aphakic design) was implanted after cataract extraction. The patient was kept on the same postoperative protocol. One week post-implantation, the UCVA improved dramatically to 20/80. However, at the two months follow up visit, corneal epithelial defect (size: 4×4 mm) without stromal melt was found on the temporal side of the KPro optic. Soft contact lens was in place and the patient did not report soft contact lens displacement/extrusion. Lateral tarsorrhaphy was done for the patient and the epithelial defect healed. The UCVA at one-year follow up visit was 20/60.

Case 3

A 55-years-old male presented with three repeated failed corneal grafts secondary to post-lasik ectasia in his left eye. His UCVA was counting fingers. The IOP of his left eye was 24 mmHg (attributed to the edematous rejected graft, central ultrasonic pachymetry of 590μ). Schirmer's test with anesthesia was 7 mm. The posterior segment B scan was within normal limits.

Clear lens extraction and Boston KPro Type I (aphakic design) was implanted. The patient's UCVA post-operative 1 week was 20/60 that improved to 20/50 at 10 months postoperative follow up. The patient's ocular condition was stable without complications till the last follow-up.

Case 4

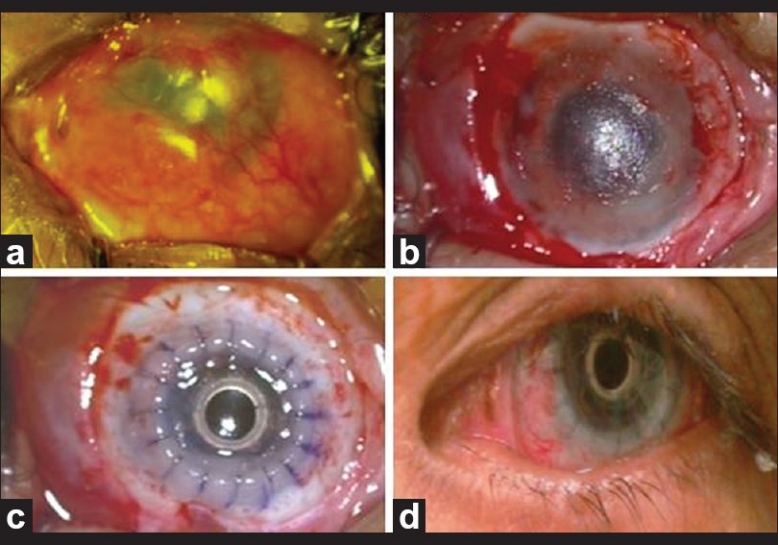

A 48-years-old female presented with multiple lid surgeries in her left eye to treat post- alkali burn cicatrization and excise fibrovascular proliferation [Figure 2a]. Cataract extraction was performed without IOL implantation. The left eye was also treated with trans-scleral cyclophotocoagulation (CPC) to control glaucoma. The UCVA in the left eye was hand motion and the IOP was 20 mmHg with medications. She was on gutt. Alphagan P 0.15% t.d.s (Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA, U.S.A) and gutt Cosopt q 12 hourly (dorzolamide hydrochloride and timolol maleate 0.5% MSD, Merck and Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA), The left eye Schirmer's test with anesthesia was 4 mm and B scan for the posterior segment was within normal limits. The overlying granulation tissue was excised and thorough tenonectomy were done [Figure 2b]. Mitomycin C soaked surgical spears (0.3mg/ml for 5 min) were applied to the 360° bare sclera to avoid any further fibrovascular proliferation followed by thorough wash with 40 cc balanced saline solution (BSS).

Figure 2.

(a) Case 4 with post-alkali burn cicatrization and dense fibrovascular proliferation (b) After excision of fibrovascular growth and tenectomy (c) After implantation of type I Boston KPro (d) 6 months post-operative visit with UCVA of 20/30

Implantation of Boston KPro Type I (aphakic design) with anterior vitrectomy was successfully done [Figure 2c]. At the end of the procedure, binocular indirect ophthalmoscope revealed advanced optic nerve cupping (0.9 × 0.9).

The patient completed six months follow up, with surprisingly UCVA of 20/30 with tunnel visual field. The patient is not only improved visually but also psychologically because of the good looking left eye [Figure 2d].

DISCUSSION

The Boston KPro provides a viable alternative for patients in whom conventional penetrating keratoplasty is likely to fail.9 Design modifications and improvement in surgical and postoperative management have improved patient outcomes.5,10,11 All our patients underwent Boston type I aphakic threadless keratoprosthesis. Visual and retention outcomes are comparable to the ones reported elsewhere in the world.

The prognosis of keratoprosthesis KPro procedures depends on the preoperative diagnosis. The difference between the best and the worst group differed markedly and has been documented to correlate well with the degree of the preoperative inflammation. According to the degree of the vision achieved and retention rate, Yaghouti and Dohlman12 classified the prognosis ranking (best to worst) as follows: 1) Graft failure in the eyes without past inflammation (corneal edema, etc.); 2)Graft failure in eyes with past inflammation (past herpes simplex or zoster, uveitis, etc.); 3) Pemphigiod (susceptible to retroprosthetic membrane formation); 4)Chemical burns (susceptible to glaucoma and retinal detachment), 5) Stevens-Johnsons syndrome (poor prognosis, high risk of endophthalmitis)

Of the 4 patients, 3 had pre-operative inflammation. Although there is little reported data on the use of Boston keratoprosthesis in trachoma eyes; our experience on 2 eyes was encouraging with one of the eyes achieving BCVA of 20/60 and the other eye 20/100 (due to associated amblyopia). The other trachoma eye, however, needed kerato-prosthesis revision due to the corneal melting resulting from the severe dry eye associated with trachoma. Surprisingly the eye with alkali burn, which was expected to be of the worst prognosis of the 4 cases, achieved BCVA of 20/30 and eye was quiet with a good control of glaucoma till the last follow up of 6 months. We researched the literature and found that Zerbe et al. have also reported good outcomes for patients with chemical burns.13

Absence of retroprosthetic membrane (RPM) in the all the 4 eyes seems to corroborate with the Chew et al's hypothesis that threadless design may reduce the formation of RPMs.14 Chew et al. hypothesized that the absence of mechanical torsional scraping of the donor corneal endothelium in the threadless design will prevent any liberation of fibroblasts and therefore decrease the likelihood of RPM formation. In addition, implantation of aphakic type I KPro in all the 4 eyes required anterior vitrectomy to be performed, which may have independently contributed to non-development of RPM. Future studies with longer follow-up may provide the relevant data to confirm this hypothesis.

Glaucoma is a frequent and severe complication after the keratoprothesis, particularly in cicatrizing conditions, such as chemical burn, etc.12 None of our 4 eyes developed glaucoma after the implantation of KPro. However, case number 4 (alkali burn) had pre-existing glaucoma, which was managed successfully with pre-KPro CPC and continuing anti-glaucoma medications post-operatively.

Ocular surface dryness is the single most important factor determining the retention rate of the Boston keratoprosthesis. Although bandage contact lens helps prevent desiccation of corneal surface and adds to the patients’ comfort by protecting from any exposed sutures and from the shearing forces of lid movements on the upper KPro edge,5 patients with extreme dry eye should be planned for type II through-the-lid KPro.

Increasing retention rates of KPro has lead to increasing acceptance and the gradual expansion of the indications. The procedure, which was reserved for patients with bilateral severe visual impairment and poor prognosis of keratoplasty, is now being considered in patients with a healthy fellow eye to improve the binocular status of those patients, either by expansion of the visual field or by recovering stereo vision.7

In consistent with the previous reports from other parts of the world, all the 4 eyes had a significant increase in vision after Boston type I keratoprosthesis implantation. Boston type I keratoprosthesis is a viable option after multiple keratoplasty failures or in conditions with a poor prognosis for primary keratoplasty. However, patients require close lifelong follow-up to monitor continued success or manage any long-term complications that may happen especially in indications like trachoma where the patho-physiological process may continue unabated.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khan B, Dudenhoefer EJ, Dohlman CH. Keratoprosthesis: an update. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12:282–7. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlap K, Chak G, Aquavella JV, Myrowitz E, Utine CA, Akpek E. Short-term visual outcomes of Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis implantation. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:687–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ilhan-Sarac O, Akpek EK. Current concepts and techniques in keratoprosthesis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2005;16:246–50. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000172829.33770.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dohlman CH, Harissi-Dagher M. The Boston Keratoprosthesis: A New Threadless Design. Digi J Opthalmol. 2007;13:6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohlman CH, Dudenhoefer EJ, Khan BF, Morneault S. Protection of the ocular surface after keratoprosthesis surgery: the role of soft contact lenses. Clao J. 2002;28:72–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dudenhoefer EJ, Nouri M, Gipson IK, Baratz KH, Tisdale AS, Dryja TP, et al. Histopathology of explanted collar button keratoprostheses: A clinicopathologic correlation. Cornea. 2003;22:424–8. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200307000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sayegh RR, Avena DL, Vargas-Martin F, Webb RH, Dohlman CH, Peli E. Optical functional properties of the Boston Keratoprosthesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:857–63. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dohlman CH, Barnes S MJ. keratoprosthesis. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, editors. Cornea. 2nd ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby–Year Book Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doane MG, Dohlman CH, Bearse G. Fabrication of a keratoprosthesis. Cornea. 1996;15:179–84. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nouri M, Terada H, Alfonso EC, Foster CS, Durand ML, Dohlman CH. Endophthalmitis after keratoprosthesis: incidence, bacterial causes, and risk factors. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:484–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.4.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan BF, Harissi-Dagher M, Khan DM, Dohlman CH. Advances in Boston keratoprosthesis: Enhancing retention and prevention of infection and inflammation. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2007;47:61–71. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e318036bd8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaghouti F, Dohlman CH. Innovations in keratoprosthesis: Proved and unproved. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1999;39:27–36. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199903910-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zerbe BL, Belin MW, Ciolino JB. Results from the multicenter Boston Type 1 Keratoprosthesis Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1779. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chew HF, Ayres BD, Hammersmith KM, Rapuano CJ, Laibson PR, Myers JS, et al. Boston keratoprosthesis outcomes and complications. Cornea. 2009;28:989–96. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181a186dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]