Abstract

The filamentous soil bacteria Streptomyces undergo a highly complex developmental programme. Before streptomycetes commit themselves to sporulation, distinct morphological checkpoints are passed in the aerial hyphae that are subject to multi-level control by the whi sporulation genes. Here we show that whi-independent expression of FtsZ restores sporulation to the early sporulation mutants whiA, whiB, whiG, whiH, whiI and whiJ. Viability, stress resistance and high-resolution electron microscopy underlined that viable spores were formed. However, spores from sporulation-restored whiA and whiG mutants showed defects in DNA segregation/condensation, while spores from the complemented whiB mutant had increased stress sensitivity, perhaps as a result of changes in the spore sheath. In contrast to the whi mutants, normal sporulation of ssgB null mutants—which fail to properly localise FtsZ—could not be restored by enhancing FtsZ protein levels, forming spore-like bodies that lack spore walls. Our data strongly suggest that the whi genes control a decisive event towards sporulation of streptomycetes, namely the correct timing of developmental ftsZ transcription. The biological significance may be to ensure that sporulation-specific cell division will only start once sufficient aerial mycelium biomass has been generated. Our data shed new light on the longstanding question as to how whi genes control sporulation, which has intrigued scientists for four decades.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10482-011-9678-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Checkpoint, Transcription, Cell division, Feedback control, Actinomycete

Introduction

Bacterial cells do not commit themselves lightly to dramatic changes in their lifestyle. Radical morphological changes, such as sporulation, stalk formation or swarming are typically made out of need for survival and controlled by major transcriptional checkpoints (Chater 2001; Grossman 1995; Wang and Levin 2009). At important junctures in the onset of cellular development, transcriptional control is coupled to the completion of landmark morphological events. It has been proposed that checkpoints also govern the activity of the whi genes that control the onset of sporulation in Streptomyces (Chater 2001). These soil-dwelling Gram-positive bacteria undergo complex morphological development and in connection to the developmental programme antibiotics and other natural products are produced (Hopwood 2007; van Wezel and McDowall 2011). Initially, streptomycetes form a network of branched hyphae, the vegetative or substrate mycelium, consisting of syncytial cells separated by occasional cross-walls (Wildermuth and Hopwood 1970). Once the checkpoint for the initiation of differentiation has been passed, the formation of an aerial mycelium is initiated, using the vegetative mycelium as a substrate (Chater 2001). The aerial hyphae then undergo several morphological stages before committing themselves to sporulation (Flärdh and Buttner 2009). In sporulation-committed aerial hyphae, FtsZ organises into spiral-shaped intermediates along the length of the aerial hyphal cell, which then assemble into multiple foci at the septum sites, eventually forming ladders of up to a hundred Z-rings (Grantcharova et al. 2005; Schwedock et al. 1997; Willemse and van Wezel 2009). The ftsZ gene is regulated from three promoters, one constitutive (p3), one primarily transcribed during vegetative growth (p1) and one primarily transcribed during sporulation (p2). Interestingly, deletion of the p2 promoter prevents sporulation-specific cell division, but vegetative division appears unaffected (Flärdh et al. 2000).

Genes essential for sporulation are called whi (white) genes, characterised by the white appearance of mutants due to the lack of the WhiE spore pigment (Chater 1972). Six whi loci, designated whiA, whiB, whiG, whiH, whiI (Chater 1972) and whiJ (Ryding et al. 1999) were identified that presumably form checkpoints in the development of aerial hyphae and spores (Chater 2001). The respective mutants fail to make the transitions through particular stages of aerial development. The whiG gene encodes a sigma factor that is required for early aerial mycelium development, with the mutant producing erect aerial hyphae that fail to coil (Chater 1989); whiB encodes a small, cysteine-rich transcription factor with many homologues in streptomycetes and mycobacteria (Soliveri et al. 2000), and mutants of whiB (as well as of the less well characterised whiA) form abundant and coiling aerial hyphae (presporulation stage). Deletion of the gntR-family regulatory gene whiH results in sporulation mutants that produce occasional sporulation septa (Flärdh et al. 1999; Ryding et al. 1999), and a direct role for WhiH in enhancing developmental ftsZ transcription has been proposed (Flärdh et al. 2000). The whiI gene encodes a response regulator-like protein controlling both early and late sporulation events (Tian et al. 2007), while whiJ encodes a likely DNA binding protein that may act as a repressor of development (Ainsa et al. 2010). Several paralogues of whiJ exist in streptomycetes that are typically flanked by abaA-like genes associated with control of antibiotic production (Gehring et al. 2000).

Still relatively little is known of how sporulation-specific cell division is controlled. In most bacteria the positioning and timing of septum formation involves the action of negative control systems such as Min, which prevents Z-ring assembly at the cell poles (Raskin and de Boer 1997; Marston et al. 1998), and nucleoid occlusion that prevents formation of the Z-ring over non-segregated chromosomes (Wu and Errington 2004). We recently showed that the formation of Z-ladders depends on the SsgB protein, which is a member of the SsgA-like proteins (SALPs), an emerging family of sporulation proteins found exclusively in morphologically complex actinomycetes (Noens et al. 2005; Traag and van Wezel 2008). Of the SALPs, SsgA (van Wezel et al. 2000a; Jiang and Kendrick 2000) and SsgB (Keijser et al. 2003) are essential for sporulation. Interestingly, the transcription of ssgA does not depend on the classical whi genes whiABGHIJ (Traag et al. 2004), which may be explained by the fact that SsgA is also involved in processes involving remodelling of the peptidoglycan during normal growth, such as germination, branching and tip growth (Noens et al. 2007) as well as submerged sporulation (Yamazaki et al. 2003).

In this work we show that sporulation is restored to the whi mutants by expression of ftsZ from a constitutive promoter, strongly suggesting that the sporulation proteins WhiA, WhiB, WhiG, WhiH, WhiI and WhiJ form a checkpoint system to correctly time the expression of FtsZ, a complicated regulatory system that may serve to ensure the production of sufficient aerial biomass prior to undergoing sporulation.

Results

FtsZ accumulation in whi mutants

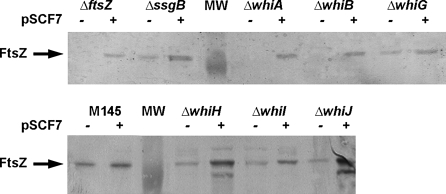

In an attempt to identify possible global causes for the sporulation block in the whi mutants we traced back the steps leading to sporulation-specific cell division. This cell division process is hampered in all whi mutants, perhaps because transcription from the developmental ftsZp2 promoter is not yet activated (Flärdh et al. 2000; Ryding et al. 1999). Transcript analysis revealed that transcriptional activity of ftsZp2 was absent in whiA and whiB mutants and very low in whiG mutants, while in whiH, whiI and whiJ mutants there was transcriptional activity, but without the strong upregulation during development that is typical of wild-type cells. To establish how the reduced expression of the p2 promoter affects FtsZ protein accumulation, protein extracts were prepared from solid-grown cultures when robust aerial mycelium was formed and analysed by Western analysis using polyclonal antibodies against FtsZ. This revealed that FtsZ was absent in mycelia of whiA and whiB mutants as well as in the control ftsZ mutant, while it was strongly reduced in whiG mutants. However, FtsZ was detected in protein samples of the whiH, whiI and whiJ mutants, which are all stalled at a later stage of aerial development (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

FtsZ levels in the whi mutants and restoration by pSCF7. Western analysis using polyclonal antibodies against FtsZ demonstrating FtsZ protein levels in protein extracts of S. coelicolor M145 (wild-type strain) as well as its sporulation mutant derivatives carrying complete deletions of the whiA, whiB, whiG, whiH, whiI, whiJ or ssgB genes. Note that introduction of pSCF7 restores FtsZ to levels similar to those found in the wild-type strain, except for whiH and whiJ mutants, which show enhanced FtsZ protein levels

Restoration of sporulation by nondevelopmental expression of ftsZ

In order to find out if the reduced expression of FtsZ in the whi mutants may be a determining factor in their failure to initiate sporulation-specific cell division, we forced FtsZ expression in aerial hyphae of the whi mutants using integrative vector pSCF7 that expresses ftsZ from the constitutive ermE promoter, resulting in FtsZ protein levels that are around twice as high as in wild-type cells [(van Wezel et al. 2000b); see also Fig. 1]. While overexpression of FtsZ from a multi-copy vector strongly inhibits development, the enhanced levels resulting from integrative vector pSCF7 lead to a slight delay of colony development in original transformants but otherwise sporulation is normal (van Wezel et al. 2000b). As controls we used pSCF1 and pSCF5 (Table S1), which are low-copy shuttle vectors harbouring ftsZ and ftsQ or ftsZ alone, respectively, with in both cases the ftsZ gene preceded by its natural promoter region, or the empty vectors (pSET152 as control for pSCF7 and pHJL401 as control for pSCF1). Both plasmid systems are suitable for genetic complementation (van Wezel et al. 2000c). The functionality of pSCF7 was confirmed by its ability to restore sporulation to the ftsZ null mutant (Fig. S1). Western analysis of the pSCF7 transformants showed that the construct enhanced FtsZ protein levels in all whi mutants (Fig. 1). FtsZ protein levels were restored to around wild-type levels for whiA, whiB, whiG and whiI mutants. Surprisingly, FtsZ levels were reproducibly enhanced in whiH and whiJ mutants as compared to the parental strain M145 harbouring the same plasmid. A second lower band was also observed in these mutants, perhaps reflecting degradation of FtsZ. In contrast, a similar experiment with samples taken from mycelia grown in TSBS media and harvested at transition phase, which corresponds to the onset of development in surface-grown cultures, showed restoration of FtsZ levels by pSCF7 to wild-type levels in all six whi mutants (Fig. S2).

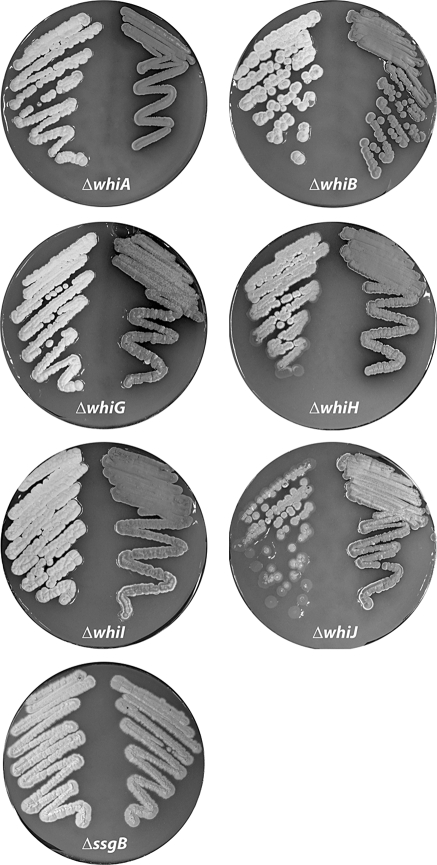

Excitingly, while the whi mutants harbouring control plasmid all showed the white phenotype typical of sporulation mutants, the constitutive expression of FtsZ resulted in the production of grey spore pigment, suggesting that sporulation had been restored to all of the whi mutants (Fig. 2). In contrast, transformation with pSCF1 expressing ftsZ from the natural promoter region did not restore sporulation to any of the whi mutants. Since pSCF1 also contains the ftsQ gene, we further tested pSCF5 (which contains a 1.6 kb DNA fragment harbouring only ftsZ and its promoter region; Table S1), and introduction of this plasmid also failed to restore sporulation to the whi mutants (not shown). A mutant lacking the ssgB gene, which encodes a structural protein required for the proper localization of FtsZ, was also analysed. ssgB mutants harbouring pSCF7B (a variant of pSCF7 based on pHM10a, which integrates at the minicircle attachment site) showed light grey pigmentation indicating that development had progressed enough to produce the WhiE spore pigment, while no pigmentation was observed for pSCF1 or the empty vectors. However, no intact spores were identified as was apparent from transmission electron microscopy and stress sensitivity tests (see below).

Fig. 2.

Expression of FtsZ from a constitutive promoter rescues the sporulation block of whi mutants. The image shows the respective whi mutants (whiA, whiB, whiG, whiH, whiI, or whiJ) with control plasmid (left), and the mutants carrying pSCF7 (right), which expresses ftsZ from the constitutive ermE promoter. The ssgB null mutant is presented as a control. Note that grey pigmentation is restored to the whi mutants but only partially to the ssgB mutant (see Fig. 3 and Fig. S3 for cryo-SEM images). Single colonies of the whiJ mutant reproducibly showed delayed aerial development. Strains were grown for 4 days on SFM agar plates at 30°C

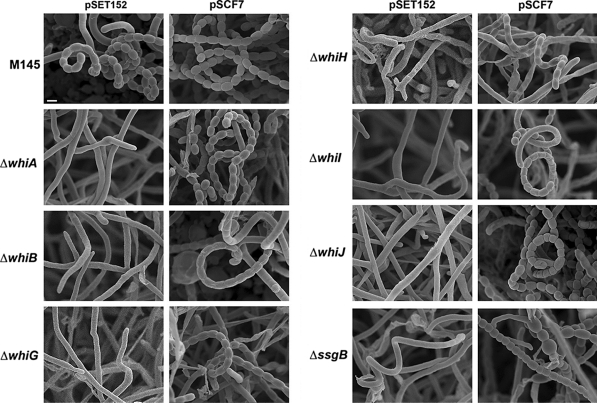

After initial scrutiny by phase-contrast microscopy, all original strains and their transformants were analysed in detail by high-resolution imaging. Cryo-scanning electron microscopy (cryo-SEM) indeed revealed that introduction of pSCF7 restored sporulation to the whiA, whiB, whiH, whiI and whiJ mutants, forming the abundant coiling spore chains similar to the parental strain M145 (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3), with similar lengths of the spore chains (those of sporulation-restored whiJ mutants were in fact longer, see below). Spore sizes (0.95–1.12 ± 0.19 μm; averages of >100 spores measured by SEM) were very similar to wild type spores (1.03 ± 0.19 μm). Partial restoration of sporulation was observed for the whiG mutant carrying pSCF7, which revealed wild-type spore chains, but with strongly reduced amount of spores, namely around 10% of wild-type levels (M145). Conversely, the whiJ mutant sporulated so abundantly that we could not observe non-sporulating sections of the aerial hyphae (Fig. S3). As could already be gleaned from the Whi phenotype of the transformants, cryo-SEM showed that neither pSCF1 (expressing ftsZ from the natural promoters) nor the empty plasmid could restore sporulation to any of the mutants (Fig. 3). Some spore-like bodies were also observed in the ssgB mutant expressing FtsZ from the ermE promoter (Fig. 3; Fig. S3), with a significantly larger variation in size (0.95 ± 0.30 μm; F-test P < 0.001) and only 44% in the size range of 0.9–1.3 μm that is typical of wild-type spores (Fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

Cryo-scanning electron micrographs of mature spore chains of the whi mutants expressing FtsZ. Column 1, S. coelicolor M145 (parental strain) and its whiA, whiB and whiG mutants harbouring control plasmid; column 2, same strains as shown in column 1 but now containing plasmid pSCF7, which expresses ftsZ from the constitutive ermE promoter; column 3, whiH, whiI, whiJ and ssgB mutants containing control plasmid; column 4, same strains as shown in column 3, but now containing plasmid pSCF7 (or pSCF7B for the ssgB mutant). Note that the constitutive expression of ftsZ restores sporulation to all whi mutants, while ssgB mutants produce spore-like bodies with highly variable sizes (see Fig. 5), most likely due to incorrect localization of FtsZ. For high-resolution TEM images of the spore chains see Fig. 5. All strains were grown for 5 days on SFM agar plates at 30°C. See Fig. S3 for lower magnification. All images presented at the same scale. Bar (top left), 1 μm

The sporulation-restored whi mutants produce viable spores

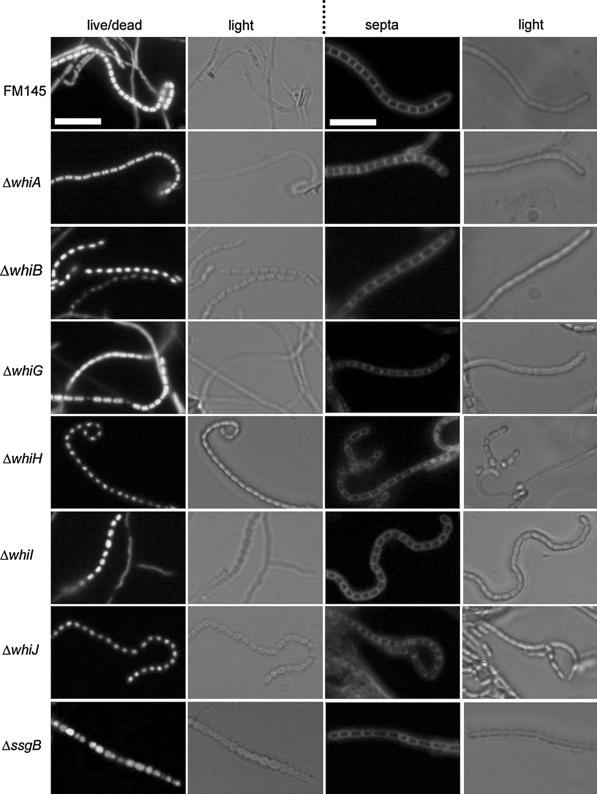

To establish to what extent sporulation had really been restored to the whi mutants, spores were analysed in more detail. Firstly, fluorescence microscopy was used to visualise septum formation (using the membrane dye FM 5-95) and for live/dead staining (combination of the green-fluorescent nucleic acid stain SYTO 82 for viable cells and the red-fluorescent nucleic acid stain propidium iodide (PI) for dead cells). The whi mutants themselves occasionally produced septa—with similar spacing as vegetative cross walls—but lack the ladders of septa typical of normal sporulation; such occasional septum formation is typical of aerial hyphae that fail to initiate sporulation-specific cell division (Grantcharova et al. 2005; Willemse et al. 2011). However, all whi mutants transformed with pSCF7 produced the septal ladders typical of sporulation-specific cell division (Fig. 4). These results are in line with the wild-type appearance of the spore chains (Fig. 3; Fig. S3). In terms of live/dead staining, no aberrant spores were detected in the pSCF7 transformants of whiA, whiB, whiH, whiI or whiJ mutants, and close to 100% of the spores gave rise to a colony (Fig. 4; Table 1), suggesting that the restoration of sporulation to these whi mutants results in spores with similar viability as the wild-type strain. However, over 10% of the spores obtained from the whiG mutant with pSCF7 were either dead (stained with propidium iodide) or empty, and in line with these imaging results, spore preparations of whiG-pSCF7 had about 10% reduced viability. Of the spore-like bodies produced by the ssgB transformants only 41% were viable, with a particularly low viability for the spores that were significantly smaller than wild-type spores. For distribution of spore sizes and viability of the spores of the ssgB transformants in comparison to wild-type spores see Fig. S4.

Fig. 4.

Viability and formation of septal ladders during sporulation of sporulation-restored whi mutants. Live/dead staining (left) and septum staining (right) is shown for the whi and ssgB mutants harbouring pSCF7. FM145 was used as the control. Live cells were identified with syto-82, dead cells with propidium iodide. Septa were highlighted by the membrane stain FM5-95. Note that several spores of the whiG and ssgB mutants were not viable (red; dark in b/w), fitting with the viability count and the incomplete restoration of sporulation. Note the multi-lobed DNA produced by whiA and whiG mutants (see Fig. S5 for deconvolution images). Transformants were grown against microscopy cover slips for 3 days on SFM agar plates. Bar, 5 μm

Table 1.

Viability of spores obtained from pSCF7 transformants of the whi mutants, the ssgB mutant and the parental strain (S. coelicolor M145)

| Strain | Viability (%)a | N | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| M145 | 100 | 248 | Reference |

| ΔwhiA | 99 | 269 | P > 0.99 |

| ΔwhiB | 100 | 307 | ND |

| ΔwhiG | 87 | 215 | P < 0.02 |

| ΔwhiH | 100 | 250 | ND |

| ΔwhiI | 100 | 200 | ND |

| ΔwhiJ | 100 | 364 | ND |

| ΔssgB | 41 | 266 | P < 0.001 |

N, number of spores counted

aBased on live/dead staining experiments

bprobability that the spores of the respective complemented mutants have similar viability as those of the parental strain M145 (ND not determined)

The whiA and whiG mutants with pSCF7 showed two or three well-separated DNA foci or ‘chromosomal lobes’ rather than uniform staining, although the total amount of DNA is similar to that in wild-type cells (Fig. 4; see Fig. S5 for deconvolution images). This aberrant DNA segregation/condensation was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (see below). Such lobed DNA is sometimes found in wild-type spores and may reflect a spore-specific nucleoid state in prespores (Dagmara Jakimowicz, personnel communication); apparently, this effect is strongly enhanced in whiA and whiG mutants. The incomplete indentation of the hyphae in light images (Fig. 4) suggests that most sporulating hyphae were still in a pre-sporulation stage (~80%). Similar multi-lobed DNA and incomplete indentation was observed for the whiG transformants (Fig. 4 and S4). This suggests that although sporulation in whiA and whiG mutants is restored, the maturation process is slowed down.

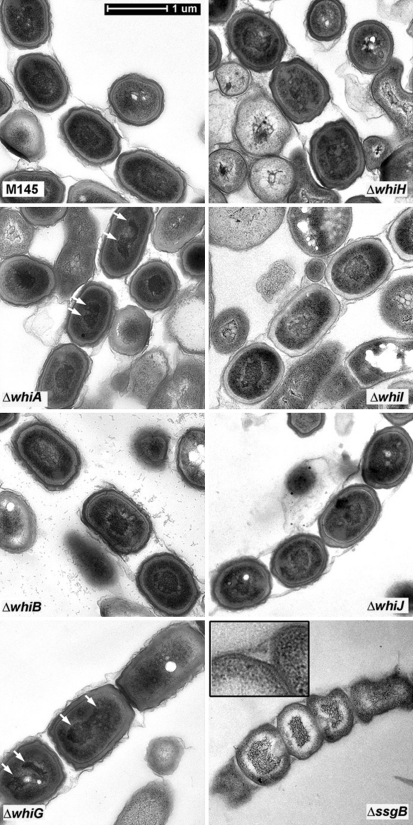

Subsequently, thin sections of the spores from the various pSCF7 transformants were prepared and analysed by high resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM). This revealed apparently normal spores for the whiB, whiH, whiI and whiJ transformants, although the spore sheaths of the whiB transformant was notably fragmented (Fig. 5). Interestingly, while also whiA and whiG transformants had apparently normal spore walls and sizes, both showed the multi-lobed DNA also observed with fluorescence microscopy (see white arrows in Fig. 5). This strongly suggests that WhiA and WhiG are required for proper DNA condensation, even in a situation where the sporulation block has been circumvented and (viable) spores were eventually produced. In contrast to the sporulation-restored whi mutants, the ‘spore chains’ that were observed for the ssgB mutant harbouring pSCF7B were highly aberrant, with the generally misshapen bodies having an entirely different appearance; the DNA had a spiky appearance and was surrounded by a white electron-lucent mass of unknown nature (Fig. 5), while the cell wall was as thin as that of aerial hyphae (see insert in Fig. 5 for a magnified example).

Fig. 5.

Transmission electron micrographs of sporulation-restored whi mutants. Thin sections of spore chains of pSCF7 transformants of S. coelicolor M145 and its whi and ssgB mutants were analysed at high resolution by transmission electron microscopy. For each of the transformants a representative spore chain is presented. Arrows indicate multi-lobed chromosomes in whiA and whiG transformants. Insert in the image for the ssgB transformant shows magnification of the thin cell wall of the spore-like bodies produced by the transformants. Bar = 1 μm

Finally, the spores were tested for resistance to heat and lysozyme treatment. Therefore, spores were diluted and incubated for 0–20 min either at 60°C or in a solution containing 2 μg/ml lysozyme (Table 2). As expected, the spore-like bodies obtained from the ssgB transformants were very sensitive to exposure to both heat and lysozyme, with hardly any colonies formed even after 5 min of either treatment. Spores from the whiA, whiG, whiH and whiI pSCF7 transformants showed similar resistance to heat treatment as the parental strain M145. However, spores of the whiB transformants were significantly more sensitive to heat treatment, with only around 10% of the spores surviving after 20 min of incubation at 60°C, while transformants of the other whi mutants and of the parent M145 showed at least 30% viability after 20 min of incubation at 60°C (Table 2). The same was observed for lysozyme treatment, with only around 20% survival for spores from whiB transformants after only 5 min incubation with lysozyme (Table 2). This may be due to the integrity of the sheath around the spores, which was found shattered in almost all spore chains, with small fragments surrounding the spores (see Fig. 5), while it was mostly intact (although occasionally broken at a single position) in the other transformants. Surprisingly, spores from the whiG and whiH transformants were more resistant to lysozyme treatment than the other transformants, with 90 and 100% survival after 20 min, respectively. The enhanced resistance of spores obtained from whiG and whiH transformants was reproducible, but scrutiny of many TEM images did not reveal statistically relevant differences in, for example, cell wall integrity or thickness as compared to wild-type spores. Transformants of ΔwhiA, ΔwhiI, ΔwhiJ and the parent M145 showed a significant decline already after 5 min of lysozyme treatment, followed by stabilization during longer incubation.

Table 2.

Heat and lysozyme resistance of spores

| Straina | Heat treatment (min)b | Lysozyme treatment (min)b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | |

| M145 | 100 | 67 | 54 | 44 | 100 | 63 | 60 | 65 |

| ΔwhiA | 100 | 100 | 63 | 63 | 100 | 79 | 50 | 56 |

| ΔwhiB | 100 | 54 | 23 | 8 | 100 | 18 | 21 | 20 |

| ΔwhiG | 100 | 54 | 50 | 30 | 100 | 82 | 89 | 89 |

| ΔwhiH | 100 | 100 | 66 | 43 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| ΔwhiI | 100 | 45 | 40 | 34 | 100 | 41 | 51 | 48 |

| ΔwhiJ | 100 | 45 | 33 | 30 | 100 | 29 | 31 | 33 |

| ΔssgB | 100 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

Survival (in percentage) of spores after heat treatment (60°C for 0–20 min) or lysozyme treatment (2 mg/ml, 0–20 min) of the spores

aAll strains harboured plasmid pSGF7

bColony forming units at t = 0 set to 100%. Spores of all transformants were freshly prepared from SFM agar plates prior to treatment. Data are averages from three independent spore preparations

Discussion

The main finding presented in this work is that the sporulation deficiency of the whiA, whiB, whiG, whiH, whiI, and whiJ sporulation mutants can be overcome by transcription of ftsZ from a nondevelopmental (constitutive) promoter. This provides compelling evidence that the correct timing of developmental ftsZ transcription is (one of) the major function(s) of the whi regulatory genes and the primary reason for the developmental arrest of the whi mutants. This finding contrasts the canonical view that the main function of the whi genes is to activate genes and processes relating to the various stages of aerial development, from early aerial growth to the onset of sporulation, and is supported by the earlier observation that the developmental transcription of ftsZ is essential for sporulation (Flärdh et al. 2000). Apparently, most if not all other processes required for aerial development and for the onset of sporulation-specific cell division can take place in the absence of at least one of the whi genes. Therefore we propose that the Whi transcription factors form a regulatory network, with their transcription tied closely to morphological checkpoints, which is directed at ensuring the correct timing of developmental FtsZ production.

Live/dead staining, viability tests (cfu counting), analysis of heat and lysozyme resistance and TEM revealed that the spores of the sporulation-restored whi transformants were viable and stress resistant. Indeed, their spores had apparently normal spore walls, except for the spore-like bodies produced by ssgB pSCF7B transformants, which lacked a spore wall, rendering them hypersensitive to heat shock and lysozyme treatment (discussed below). Surprisingly, spores of the whiG and whiH transformants were significantly more resistant to lysozyme treatment than wild-type spores, perhaps as a result of structural differences in the spore wall, although these could not be detected by electron or fluorescence microscopy. Conversely, spores from whiB transformants were more sensitive to both heat and lysozyme treatment than the parental strain M145. TEM images revealed a shattered sheath around the spore chains of the sporulation-restored whiB mutants, suggesting that the higher stress sensitivity may be caused by structural changes in the protective sheath.

The failure to completely restore sporulation to the whiG mutant indicates that WhiG plays an important role in the control of other events during aerial development. It is not clear what the exact WhiG regulon is, but it includes whiH and whiI (Flärdh et al. 1999; Ainsa et al. 1999; Ryding et al. 1998), which can both be fully restored to normal sporulation by increasing FtsZ levels. Interestingly, both sporulation-restored whiA and whiG mutants showed multi-lobed DNA in the spores (as shown by both TEM and fluorescence microscopy), suggesting a defect in DNA condensation in these transformants. It was shown recently that WhiA, WhiG and WhiI are all required for the transcription of hupS, encoding one of the two Hu-like nucleoid-associated proteins in streptomycetes (Salerno et al. 2009). Such defective transcription of hupS may well explain the defects in DNA segregation in sporulation-restored whiA and whiG mutants, although it was not apparent in sporulation-restored whiI transformants. Deletion of smc (for structural maintenance of chromosomes) or scpAB (for segregation and condensation proteins) also strongly affects DNA condensation and segregation of the chromosomes during sporulation (Dedrick et al. 2009; Kois et al. 2009), but it is unknown if their transcription is controlled by the Whi proteins. While it seems likely that chromosome condensation and segregation are linked to the morphological checkpoints discussed above, strains in which sporulation septation was blocked by mutation of a sporulation-specific ftsZp2 promoter (Flärdh et al. 2000) showed normal activation of parAB transcription and proper localization of ParB in the aerial hyphae, which seems to argue against strong coupling between cell division and DNA partitioning (Jakimowicz et al. 2006). The coordination of cell division and chromosome partitioning during sporulation requires further investigation.

In contrast to the Whi proteins, which all carry DNA binding domains and are therefore likely regulatory proteins, SsgB has a structural role and acts in a way similar as ZipA, with both proteins connecting the Z-ring to the cell wall and stimulating the polymerization of FtsZ in vitro (Hale and de Boer 1997; Willemse et al. 2011). In line with the idea that nondevelopmental expression of FtsZ overrides specifically the Whi-mediated control system, and not just any sporulation mutant, introduction of an FtsZ-expressing plasmid in ssgB null mutants did not restore sporulation. Some deformed spore-like bodies were produced, similar to ssgB mutants complemented with ssgB orthologues from other actinomycetes (Xu et al. 2009), but considering among others the extremely high sensitivity to lysozyme and heat treatment and the obvious lack of a typical spore wall (see insert in Fig. 5) these could not be described as proper spores. The lack of a spore wall is the opposite phenotype of crp null mutants, which produce spores with a wall that is more than twice as thick as that of wild-type spores (Piette et al. 2005). Comparing the crp and ssgB mutants could provide interesting leads towards the study of proteins involved in (the control of) spore-wall synthesis.

It was suggested previously that the failure of whiA and whiB mutants to sporulate was due to their inability to stop aerial growth prior to sporulation (Flärdh et al. 1999). However, the restoration of sporulation by the expression of FtsZ in these mutants argues against this idea. It appears that the growth cessation checkpoint in aerial hyphae is most likely linked to the localization of SsgB at the future septum sites, as shown by the large-colony phenotype of ssgB null mutants, which form extremely large (‘immortal’) colonies (Keijser et al. 2003). Such a large-colony phenotype is not shown by any of the other whi mutants (data not shown).

Surprisingly, enhanced expression of FtsZ in whiJ mutants resulted in what is best described as hyper-sporulation, producing extremely long spore chains, whereby the entire aerial hyphae are converted into spores (Fig. S3). Earlier work suggested that WhiJ may repress developmental genes. Mutant J2452 contains a hyg cassette inserted downstream of the part of whiJ that encodes the DNA binding domain, and expression of this domain most likely causes the Whi phenotype (Ainsa et al. 2010). In contrast, complete deletion of whiJ does not visibly affect development (Ainsa et al. 2010), and the formation of extremely long spore chains which apparently include the entire aerial hyphae by the sporulation-restored whiJ mutants (presented in this work), suggests that such repression includes controlling the length of the sporogenic part of the aerial hyphae.

Concluding remarks and future perspective

In terms of the control of aerial development several important questions remain to be answered. For example, what other processes are controlled by the whi genes besides the correct timing of sporulation-specific FtsZ expression? Many attempts have been made to identify each of the individual Whi regulons and their primary (direct) target genes, such as for WhiB and WhiH, but have been hampered by the poor functionality of proteins heterologously produced in E. coli, perhaps as a result of incorrect posttranslational processing. However, modern technologies such as ChIP-on-chip now allow determining the primary response regulons in vivo. Another well-studied developmental regulatory network is that governed by the bld genes. While originally primarily considered for their role in controlling the events that take place during the switch from vegetative to aerial growth (Nodwell et al. 1999), the pleiotropic control of late developmental genes by BldD (den Hengst et al. 2010) and the sharp increase of bldN transcription during sporulation (Bibb et al. 2000) indicate that at least some of the Bld proteins also control gene expression during aerial growth and sporulation. Detailed insight into the regulatory networks controlled by the Bld and Whi proteins will further our understanding of precisely how the highly complex sporulation process in streptomycetes is controlled.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

For strains and plasmids see Table S1. pSCF7 is an integrative vector based on pSET152 (Bierman et al. 1992), with ftsZ expressed from the constitutive ermE promoter (van Wezel et al. 2000b). All plasmids were introduced by protoplast transformation. Derivative pSCF7B was created by cloning the insert of pSCF7 into the hygromycin resistant integrative vector pHM10a, which allows integration at the minicircle attachment site (Motamedi et al. 1995). All mutants described in this work were derived from the wild-type strain S. coelicolor M145. The whi mutants J2401 (M145 whiA::hyg), J2402 (M145 whiB::hyg), J2400 (M145 whiG::hyg), J2403 (M145 whiH::hyg), J2450 (M145 whiI::hyg) and J2452 (M145 whiJ::hyg) were obtained from the John Innes Centre strain collection. The ftsZ null mutant HU133 (ftsZ::aph; (McCormick et al. 1994)) was a kind gift from Joe McCormick. GSB1 has the ssgB gene replaced by the apramycin resistance cassette aacC4 (Keijser et al. 2003).

Protein extracts and western analysis

For preparation of protein extracts from solid-grown cultures, mycelia were grown on SFM agar plates (Kieser et al. 2000) overlaid with cellophane discs, and when robust aerial mycelium was formed (around 48 h after inoculation) mycelia were scraped from the surface, washed and resuspended in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7); for liquid-grown cultures we used TSBS media (tryptic soy broth with 10% sucrose) and cultures were grown until transition phase. Mycelia were then sonicated, followed by 15 min centrifugation at 30,000×g to remove the cell debris. The protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad). 20 μg of protein was analysed by SDS–PAGE and blotted to nitrocellulose filters. Subsequently, blots were incubated with 1:1000000 dilution of FtsZ antibodies. Following washing and incubation with GARAP as secondary antibody, alkaline phosphatase detection was used to visualise the bands. Two independent replicates were performed for all samples.

Microscopy

Electron microscopy

Morphological studies on surface grown aerial hyphae and/or spores by cryo-scanning electron microscopy were performed using a JEOL JSM6700F scanning electron microscope as described previously (Colson et al. 2008). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for the analysis of cross-sections of hyphae and spores was performed with a Philips EM410 transmission electron microscope as described previously (van Wezel et al. 2000a).

Fluorescence microscopy

Cell membranes were stained with FM® 5-95 and the ratio of live/dead cells was determined by staining nucleic acids with green-fluorescent SYTO® 82 (540/560 nm) and the red-fluorescent PI (propidium iodide; 535/617 nm). Staining and imaging was done as described previously (Willemse et al. 2011). All dyes were obtained from Molecular Probes, Inc (Eugene). All images were background corrected setting the signal outside the hyphae to zero.

Viability tests

Freshly harvested spores were diluted in 20% glycerol to a concentration of 4 × 106 colony forming units (cfu) per ml before treatment. Subsequently, 2 ml of spores were treated with lysozyme (2 mg/ml) for 5, 10 and 20 min, or incubated at 60°C (heat treatment) for 5, 10 and 20 min. At each time point a 10 μl aliquot was taken and plated following a tenfold dilution series onto SFM agar plates, Plates were then cultivated for 2 days at 30°C followed by cfu counting. Percentage of survival was calculated as the number of colonies grown on the plates after treatment at 60°C divided by the number of colonies grown on plates without treatment at 60°C in percentage.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dagmara Jakimowicz for discussions and for sharing unpublished data, to Keith Chater, Klas Flärdh and Bjørn Traag for discussions, to Maureen Bibb and Mark Buttner for providing the whi mutants, to Joe McCormick for providing the ftsZ mutant and to Jos Onderwater for help with electron microscopy.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Ainsa JA, Parry HD, Chater KF. A response regulator-like protein that functions at an intermediate stage of sporulation in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:607–619. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsa JA, Bird N, Ryding NJ, Findlay KC, Chater KF. The complex whiJ locus mediates environmentally sensitive repression of development of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2010;98:225–236. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9443-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibb MJ, Molle V, Buttner MJ. sigma(BldN), an extracytoplasmic function RNA polymerase sigma factor required for aerial mycelium formation in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4606–4616. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.16.4606-4616.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman M, Logan R, O’Brien K, Seno ET, Rao RN, Schoner BE. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene. 1992;116:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chater KF. A morphological and genetic mapping study of white colony mutants of Streptomyces coelicolor. J Gen Microbiol. 1972;72:9–28. doi: 10.1099/00221287-72-1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chater KF. Multilevel regulation of Streptomyces differentiation. Trends Genet. 1989;5:372–377. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(89)90172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chater KF. Regulation of sporulation in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): a checkpoint multiplex? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:667–673. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(01)00267-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson S, van Wezel GP, Craig M, Noens EE, Nothaft H, Mommaas AM, Titgemeyer F, Joris B, Rigali S. The chitobiose-binding protein, DasA, acts as a link between chitin utilization and morphogenesis in Streptomyces coelicolor. Microbiology. 2008;154:373–382. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/011940-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedrick RM, Wildschutte H, McCormick JR. Genetic interactions of smc, ftsK, and parB genes in Streptomyces coelicolor and their developmental genome segregation phenotypes. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:320–332. doi: 10.1128/JB.00858-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hengst CD, Tran NT, Bibb MJ, Chandra G, Leskiw BK, Buttner MJ. Genes essential for morphological development and antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor are targets of BldD during vegetative growth. Mol Microbiol. 2010;78:361–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flärdh K, Buttner MJ. Streptomyces morphogenetics: dissecting differentiation in a filamentous bacterium. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:36–49. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flärdh K, Findlay KC, Chater KF. Association of early sporulation genes with suggested developmental decision points in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Microbiology. 1999;145:2229–2243. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-9-2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flärdh K, Leibovitz E, Buttner MJ, Chater KF. Generation of a non-sporulating strain of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) by the manipulation of a developmentally controlled ftsZ promoter. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:737–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring AM, Nodwell JR, Beverley SM, Losick R. Genome wide insertional mutagenesis in Streptomyces coelicolor reveals additional genes involved in morphological differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9642–9647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170059797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantcharova N, Lustig U, Flärdh K. Dynamics of FtsZ assembly during sporulation in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3227–3237. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.3227-3237.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AD. Genetic networks controlling the initiation of sporulation and the development of genetic competence in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:477–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CA, de Boer PA. Direct binding of FtsZ to ZipA, an essential component of the septal ring structure that mediates cell division in E. coli. Cell. 1997;88:175–185. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood DA. Streptomyces in nature and medicine: the antibiotic makers. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jakimowicz D, Mouz S, Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J, Chater KF. Developmental control of a parAB promoter leads to formation of sporulation-associated ParB complexes in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:1710–1720. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.5.1710-1720.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Kendrick KE. Characterization of ssfR and ssgA, two genes involved in sporulation of Streptomyces griseus. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5521–5529. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.19.5521-5529.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keijser BJ, Noens EE, Kraal B, Koerten HK, van Wezel GP. The Streptomyces coelicolor ssgB gene is required for early stages of sporulation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;225:59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. Practical Streptomyces genetics. Norwich: The John Innes Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kois A, Swiatek M, Jakimowicz D, Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J. SMC protein-dependent chromosome condensation during aerial hyphal development in Streptomyces. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:310–319. doi: 10.1128/JB.00513-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston AL, Thomaides HB, Edwards DH, Sharpe ME, Errington J (1998) Polar localization of the MinD protein of Bacillus subtilis and its role in selection of the mid-cell division site. Genes Dev 12:3419–3430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCormick JR, Su EP, Driks A, Losick R. Growth and viability of Streptomyces coelicolor mutant for the cell division gene ftsZ. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:243–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motamedi H, Shafiee A, Cai SJ. Integrative vectors for heterologous gene expression in Streptomyces spp. Gene. 1995;160:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nodwell JR, Yang M, Kuo D, Losick R. Extracellular complementation and the identification of additional genes involved in aerial mycelium formation in Streptomyces coelicolor. Genetics. 1999;151:569–584. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noens EE, Mersinias V, Traag BA, Smith CP, Koerten HK, van Wezel GP. SsgA-like proteins determine the fate of peptidoglycan during sporulation of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:929–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noens EE, Mersinias V, Willemse J, Traag BA, Laing E, Chater KF, Smith CP, Koerten HK, van Wezel GP. Loss of the controlled localization of growth stage-specific cell-wall synthesis pleiotropically affects developmental gene expression in an ssgA mutant of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:1244–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette A, Derouaux A, Gerkens P, Noens EE, Mazzucchelli G, Vion S, Koerten HK, Titgemeyer F, De Pauw E, Leprince P, van Wezel GP, Galleni M, Rigali S. From dormant to germinating spores of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): new perspectives from the crp null mutant. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:1699–1708. doi: 10.1021/pr050155b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin DM, de Boer PA (1997) The MinE ring: an FtsZ-independent cell structure required for selection of the correct division site in E. coli. Cell 91:685–694 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ryding NJ, Kelemen GH, Whatling CA, Flärdh K, Buttner MJ, Chater KF. A developmentally regulated gene encoding a repressor-like protein is essential for sporulation in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:343–357. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryding NJ, Bibb MJ, Molle V, Findlay KC, Chater KF, Buttner MJ. New sporulation loci in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5419–5425. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5419-5425.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno P, Larsson J, Bucca G, Laing E, Smith CP, Flärdh K. One of the two genes encoding nucleoid-associated HU proteins in Streptomyces coelicolor is developmentally regulated and specifically involved in spore maturation. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6489–6500. doi: 10.1128/JB.00709-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwedock J, Mccormick JR, Angert ER, Nodwell JR, Losick R. Assembly of the cell division protein FtsZ into ladder like structures in the aerial hyphae of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:858. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliveri JA, Gomez J, Bishai WR, Chater KF. Multiple paralogous genes related to the Streptomyces coelicolor developmental regulatory gene whiB are present in Streptomyces and other actinomycetes. Microbiology. 2000;146:333–343. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-2-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Fowler K, Findlay K, Tan H, Chater KF. An unusual response regulator influences sporulation at early and late stages in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:2873–2885. doi: 10.1128/JB.01615-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traag BA, van Wezel GP. The SsgA-like proteins in actinomycetes: small proteins up to a big task. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2008;94:85–97. doi: 10.1007/s10482-008-9225-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traag BA, Kelemen GH, Van Wezel GP. Transcription of the sporulation gene ssgA is activated by the IclR-type regulator SsgR in a whi-independent manner in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:985–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel GP, McDowall KJ. The regulation of the secondary metabolism of Streptomyces: new links and experimental advances. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;28:1311–1333. doi: 10.1039/c1np00003a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel GP, van der Meulen J, Kawamoto S, Luiten RG, Koerten HK, Kraal B. ssgA is essential for sporulation of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) and affects hyphal development by stimulating septum formation. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5653–5662. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.20.5653-5662.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel GP, van der Meulen J, Taal E, Koerten H, Kraal B. Effects of increased and deregulated expression of cell division genes on the morphology and on antibiotic production of streptomycetes. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2000;78:269–276. doi: 10.1023/A:1010267708249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel GP, White J, Hoogvliet G, Bibb MJ. Application of redD, the transcriptional activator gene of the undecylprodigiosin biosynthetic pathway, as a reporter for transcriptional activity in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) and Streptomyces lividans. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;2:551–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JD, Levin PA. Metabolism, cell growth and the bacterial cell cycle. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:822–827. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildermuth H, Hopwood DA. Septation during sporulation in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;60:51–59. doi: 10.1099/00221287-60-1-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemse J, van Wezel GP. Imaging of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) with reduced autofluorescence reveals a novel stage of FtsZ localization. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemse J, Borst JW, de Waal E, Bisseling T, van Wezel GP. Positive control of cell division: FtsZ is recruited by SsgB during sporulation of Streptomyces. Genes Dev. 2011;25:89–99. doi: 10.1101/gad.600211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LJ, Errington J (2004) Coordination of cell division and chromosome segregation by a nucleoid occlusion protein in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 117:915–925 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xu Q, Traag BA, Willemse J, McMullan D, Miller MD, Elsliger MA, Abdubek P, Astakhova T, Axelrod HL, Bakolitsa C, Carlton D, Chen C, Chiu HJ, Chruszcz M, Clayton T, Das D, Deller MC, Duan L, Ellrott K, Ernst D, Farr CL, Feuerhelm J, Grant JC, Grzechnik A, Grzechnik SK, Han GW, Jaroszewski L, Jin KK, Klock HE, Knuth MW, Kozbial P, Krishna SS, Kumar A, Marciano D, Minor W, Mommaas AM, Morse AT, Nigoghossian E, Nopakun A, Okach L, Oommachen S, Paulsen J, Puckett C, Reyes R, Rife CL, Sefcovic N, Tien HJ, Trame CB, van den Bedem H, Wang S, Weekes D, Hodgson KO, Wooley J, Deacon AM, Godzik A, Lesley SA, Wilson I, van Wezel GP. Structural and functional characterizations of SsgB, a conserved activator of developmental cell division in morphologically complex actinomycetes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:25268–25279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H, Ohnishi Y, Horinouchi S. Transcriptional switch on of ssgA by A-factor, which is essential for spore septum formation in Streptomyces griseus. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1273–1283. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.4.1273-1283.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.