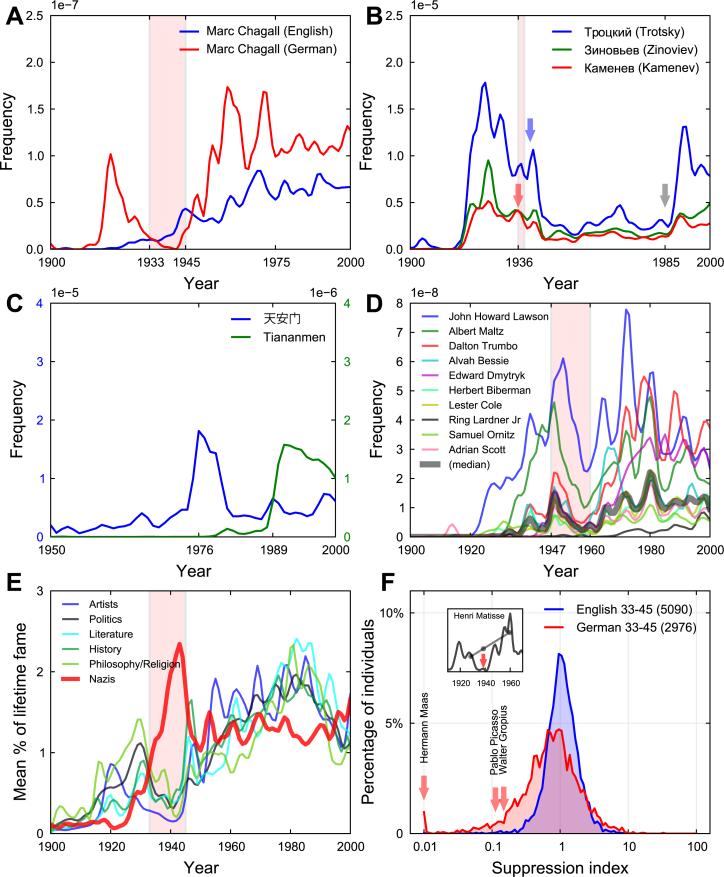

Fig. 4.

Culturomics can be used to detect censorship. (A) Usage frequency of ‘Marc Chagall’ in German (red) as compared to English (blue). (B) Suppression of Leon Trotsky (blue), Grigory Zinoviev (green), and Lev Kamenev (red) in Russian texts, with noteworthy events indicated: Trotsky's assassination (blue arrow), Zinoviev and Kamenev executed (red arrow), the ‘Great Purge’ (red highlight), perestroika (grey arrow). (C) The 1976 and 1989 Tiananmen Square incidents both lead to elevated discussion in English texts. Response to the 1989 incident is largely absent in Chinese texts (blue), suggesting government censorship. (D) After the ‘Hollywood Ten’ were blacklisted (red highlight) from American movie studios, their fame declined (median: wide grey). None of them were credited in a film until 1960's (aptly named) ‘Exodus’. (E) Writers in various disciplines were suppressed by the Nazi regime (red highlight). In contrast, the Nazis themselves (thick red) exhibited a strong fame peak during the war years. (F) Distribution of suppression indices for both English (blue) and German (red) for the period from 1933-1945. Three victims of Nazi suppression are highlighted at left (red arrows). Inset: Calculation of the suppression index for ‘Henri Matisse’.