Abstract

The chemokine CCL5 (RANTES) plays active promalignancy roles in breast malignancy. The secretion of CCL5 by breast tumor cells is an important step in its tumor-promoting activities; therefore, inhibition of CCL5 secretion may have antitumorigenic effects. We demonstrate that, in breast tumor cells, CCL5 secretion necessitated the trafficking of CCL5-containing vesicles on microtubules from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the post-Golgi stage, and CCL5 release was regulated by the rigidity of the actin cytoskeleton. Focusing on the 40s loop of CCL5, we found that the 43TRKN46 sequence of CCL5 was indispensable for its inclusion in motile vesicles, and for its secretion. The TRKN-mutated chemokine reached the Golgi, but trafficked along the ER-to-post-Golgi route differently than the wild-type (WT) chemokine. Based on the studies showing that the 40s loop of CCL5 mediates its binding to glycosaminoglycans (GAG), we analyzed the roles of GAG in regulating CCL5 secretion. TRKN-mutated CCL5 had lower propensity for colocalization with GAG in the Golgi compared to the WT chemokine. Secretion of WT CCL5 was significantly reduced in CHO mutant cells deficient in GAG synthesis, and the WT chemokine acquired an ER-like distribution in these cells, similar to that of TRKN-mutated CCL5 in GAG-expressing cells. The release of WT CCL5 was also reduced after inhibition of GAG presence/synthesis by intracellular expression of heparanase, inhibition of GAG sulfation, and sulfate deprivation. The need for a 43TRKN46 motif and for a GAG-mediated process in CCL5 secretion may enable the future design of modalities that prevent CCL5 release by breast tumor cells.

Introduction

The inflammatory milieu plays a key role in regulating tumor growth and progression [1–3]. A growing number of studies suggest that the inflammatory CC chemokine CCL5 (also known as RANTES) has major tumor-supporting activities in several cancer diseases [4,5]. CCL5 was extensively studied in breast cancer, where it was shown to causatively promote malignancy [4,5]. The chemotactic properties of CCL5 lead to elevated levels of deleterious tumor-associated macrophages in breast tumors, and it was suggested that this chemokine recruits inflammatory TH17 cells to the tumor site [6–9]. In parallel, the chemokine promotes the release of matrix-degrading enzymes by the tumor cells [7,10] and induces their migration and invasion [10–19]. Particularly, the chemokine was shown to promote the invasiveness of cells having the CD44+/CD24- phenotype of tumor-initiating cells [19].

The importance of CCL5 in breast cancer is reinforced by the fact that its inhibition has led to reduced malignancy in animal model systems of breast cancer, indicating that the chemokine has a causative role in promoting breast cancer [6,8,13,20–22]. In line with the above, CCL5 was intimately linked with advanced and aggressive disease in patients and with lymph node involvement and was suggested as a potential prognostic factor predicting progression in stage II breast cancer patients [19,23–26].

In biopsies of breast cancer patients, the most important source for CCL5 is the cancer cells themselves [5,9,19,23–30]. Recent studies indicate that the expression of the procancerous chemokine CCL5 is acquired in the course of malignant transformation, and its release by the tumor cells enables its paracrine and autocrine activities on cells of the tumor microenvironment and on the tumor cells, respectively [4,5,19,27,31]. Therefore, the secretion of CCL5 by breast cancer cells is a key regulatory step whose inhibition may lead to a significant reduction in the tumor-promoting activities induced by this chemokine.

The aim of the present study was to characterize the mechanisms that control the secretion of CCL5 by breast tumor cells. Specifically, we wished to identify chemokine domains that are required for CCL5 secretion and cellular components that regulate the release of this chemokine by breast tumor cells. The findings of this study indicate that the chemokine is mobilized in well-organized vesicles on microtubules from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the post-Golgi stage and that its release by the tumor cells is an actin-regulated process. Furthermore, by using a mutated CCL5, we have identified a four-amino-acid motif in the 40s region of CCL5, 43TRKN46, that is essential for its inclusion in motile vesicles and for its secretion by breast cancer cells. We have also shown that glycosaminoglycans (GAG) play an important regulatory role, although partial, in mediating CCL5 release by the tumor cells.

The above results indicate that the 43TRKN46 sequence of CCL5 and intracellular GAG are essential for the secretion of CCL5. When these results are considered with additional findings provided in this study, and in the literature, we suggest that one of the mechanisms that mediate the secretion of CCL5 by breast tumor cells is based on the association of the 40s loop of CCL5 with intracellular GAG that make their way to the cell surface or to the cell exterior. The identification of a 43TRKN46-mediated and GAG-mediated process of CCL5 secretion may set the basis for the future design of inhibitors that would reduce the secretion of CCL5 by breast tumor cells and thus may limit CCL5-dependent processes that are involved in breast malignancy.

Materials and Methods

Cell Cultures

The MCF-7 and T47D human breast carcinoma cell lines were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) as described previously [24]. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in DMEM as above. MCF-10A cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 5% horse serum, 10 µg/ml insulin, 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (all purchased from Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel), 100 ng/ml cholera toxin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and 0.5 µg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma). WI-38 cells (kindly provided by Prof Rotter, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel) were cultured in minimum essential medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 250 ng/ml amphotericin (Biological Industries). Human mammary normal epithelial cells (HMECs; kindly provided by Dr Berger, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel) were cultured in MEGM Ready Medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD). CHO-K1 and CHO-pgsA-745 cells (kindly provided by Prof Vlodavsky, Technion, Haifa, Israel) were cultured in DMEM and RPMI 1640 medium, respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 250 ng/ml amphotericin (Biological Industries).

Before the different experimental procedures, the various cell lines were transferred to their corresponding serum-free media, except for MCF-10A cells that were transferred to LPM medium (Biological Industries).

Chemokine Sequences

The vector used in most analyses in this study was pEGFP-N1, expressing WT or 43TRKN46-mutated CCL5 (Table 1). The constructs of WT and mutated CCL5 were produced by polymerase chain reaction, and the sequences of both chemokines were validated by full-length sequencing. In parallel, we used the pcDNA3.1-zeo(-) vector, expressing HA-tagged WT CCL5, whose sequence was validated by full-length sequencing.

Table 1.

Sequences of GFP-CCL5(WT) and GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) Used in the Study.

| The sequences of the GFP-CCL5(WT) and GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) are presented starting at their 34th amino acid. The sequence that was mutated to alanines (43TRKN46) is underlined. |

|

Bioinformatics Analysis of Chemokine Structure

Models were built using Rosetta 3.1 AbinitioRelax protocol, with protein structure prediction using Rosetta [32]. The sequence of the TRKN-mutated CCL5 [named CCL5(TRKN-)], SPYSSDTTPCCFAYIARPLPRAHIKEYFYTSGK CSNPAVVFVAAAARQVCANPEKKWVREYINSLEMS, was superimposed on the x-ray structure of WT CCL5 (PDB 1U4M [33]; the modeling started at amino acid 14 because the mutated chemokine was modeled as monomer, whereas the x-ray structure of WT CCL5 was of a dimer, in which the N′ is differently organized compared to the monomer). To predict the appropriate folding of the mutated CCL5 protein, an ab initio protocol was applied, which predicts the structure of a protein based on its sequence. The final model presented was chosen out of 10,000 decoys, based on their lowest score. The model was further assessed using the MolProbity Web server [34], which examines psi and phi angles, C-beta deviations, atom clashes, and rotamers.

Transfection and Determination of Transfection Yields

MCF-7 and T47D cells were transfected by electroporation as described previously [35]. The other cell types were transfected by ICA Fectin 441 DNA transfection reagent (MedProbe, Oslo, Norway) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transfection outcome was evaluated by flow cytometry analyses (fluorescence-activated cell sorter [FACS]). The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 0.02% sodium azide, and the expression of GFP was determined with a Becton Dickinson FACSort (Mountain View, CA) using the CellQuest software.

Determination of CCL5 Secretion by ELISA

The different cell types were grown in serum-free medium for 24 to 48 hours. In specific cases, the cells were treated by brefeld in A (BFA; Sigma; in two experiments, we used 5 µg/ml BFA for 2 hours, and in one additional experiment, we used 25 µg/ml for 5 hours; the two conditions yielded similar results), by latrunculin (5 µg/ml; Sigma), or by jasplakinolide [10-6 M; Alexis, Farmingdale, NY]) for 2 hours at 37°C. In other cases, the cells were treated by BFA for 20 minutes at room temperature. When the cells were treated by nocodazole (15 µg/ml; Sigma), they were incubated as follows: 15 minutes at 4°C without the drug; 15 minutes at 4°C with the drug; 1.5 hours at 37°C with the drug. Treatment with sodium chlorate (30 mM; Sigma) was performed for 48 hours at 37°C. In all cases, control treatments included incubation of the cells with the relevant diluents of the reagents for similar periods. The inhibitors did not affect cell viability.

When sulfate deprivation was induced, the cells were grown for 48 hours with magnesium sulfate-deprived medium (Biological Industries; to replenish the magnesium, a similar quantity of magnesium chloride was added to the medium). Control cells were grown with regular DMEM.

In other experiments, MCF-7 cells were transiently or stably transfected with a myc-tagged pSecTag vector-expressing heparanase or with an empty vector as control (kindly provided by Prof I. Vlodavsky, Technion, Haifa, Israel). In parallel, the cells were transiently transfected with GFP-CCL5 (WT).

Chemokine levels in cell supernatants were determined by ELISA, using standard curves with recombinant human CCL5 at the linear range of absorbance. The ELISA analyses were performed in the following manners: Procedure 1. Unless otherwise indicated, the ELISA studies were performed with antibodies against CCL5: coating—mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against human CCL5 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ); detection—biotinylated polyclonal goat anti-human CCL5 antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Procedure 2. Coating—mouse mAb against GFP (Covance, Princeton, NJ; MBL International, Woburn, MA); detection—biotinylated polyclonal rabbit anti-GFP antibodies (Sigma). Procedure 3. Coating—mouse mAb against GFP (Covance); detection—biotinylated polyclonal goat anti-human CCL5 antibodies (PeproTech). Procedure 4. Coating—polyclonal rabbit antibodies against human CCL5 (PeproTech); detection—biotinylated polyclonal goat anti-human CCL5 antibodies (PeproTech). P values were calculated by Student's t test.

Determination of CCL5 Expression by Western Blot Analysis

MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected with vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT), GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) or GFP only. The proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates by mouse mAb against GFP (Covance), and Western blot for GFP was performed by mouse mAb against GFP (Covance).

Confocal Analyses

Cells transiently transfected with vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT), GFP-CCL5(TRKN-), GFP only, or HA-CCL5(WT) were grown in growth medium on coverslips for 24 hours and then in serum-free medium for another 24 hours at 37°C. Actin polymerization was detected by phalloidin (40 minutes; Molecular Probes, Poort Gebouw, the Netherlands) after cell fixation and permeabilization [36].

To determine the localization of CCL5 in the ER, staining was performed with rabbit antibodies against calnexin (Sigma), then with DyLight 549-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). To determine the localization of CCL5 in the Golgi, a vector expressing the Golgi marker a mannosidase IB, tagged by HA, was expressed by transfection in the cells. HA was detected by rabbit antibodies against HA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), then stained by DyLight 549-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). Negative controls included cell staining by secondary antibodies only, as well as by an isotype-matched nonrelevant antibody (data not shown). In this set of experiments, stained cells were imaged by Zeiss LSM-510 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Determination of colocalization of GFP-CCL5(WT) or GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) with markers of the ER or of the Golgi was performed by Slidebook software (Slidebook, Denver, CO), applied on a large number of cells.

In parallel, experiments were performed to determine the colocalization of GFP-CCL5(WT) or GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) with GAG in the Golgi. In these experiments, MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected by constructs expressing GFP-CCL5(WT) or GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) and simultaneously with the Golgi marker a mannosidase IB, tagged by HA. The cells were stained with Texas Red-labeled Lycopersicon Esculentum (Tomato) Lectin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and with rabbit antibodies against HA (Santa Cruz), followed by Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) highly cross-adsorbed antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Stained cells were imaged with Zeiss LSM-510 confocal microscope and with spinning disk confocal microscope, carried out with Axiovert 200M microscope (Zeiss) coupled to a Yokogawa CSU-22 spinning disk confocal head (Yokogawa, Sugar Land, TX). Slidebook software was used for determination of colocalization of GFP-CCL5(WT) or GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) with GAG in the Golgi.

In additional experiments, HA-CCL5(WT) was detected in the cells, stained by antibodies against HA (as above), and then with DyLight 549-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). Analysis was performed with Zeiss LSM-510 confocal microscopy, as above.

Live Cell Imaging

MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected by vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT) or GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) and, 48 hours later, were imaged by live cell spinning disk confocal microscopy. Two-dimensional time-lapse series were acquired with a 3-second interval. To visualize the paths taken by moving vesicles containing GFP-CCL5(WT), images were projected in two dimensions using the maximum-value-per-pixel algorithm of Slidebook. The two dimensional algorithm was pseudo-colored in red and expanded through the entire time-lapse series.

Results

Vesicles Containing CCL5 Are Shuttled from the ER to the Post-Golgi Stage, Leading to CCL5 Secretion by Breast Tumor Cells

In the present study, we wished to identify CCL5 domains and intracellular components regulating the secretion of the chemokine by breast tumor cells and to detect intracellular regulatory determinants of CCL5 secretion. To this end, we have expressed in the tumor cells GFP-tagged human wild-type (WT) CCL5, namely GFP-CCL5(WT). At first, we wished to guarantee that the GFP-tagged CCL5 acts in similar manners to those characterized for endogenous CCL5 that is constitutively produced by the same tumor cells [27] and to further extend our understanding of basic mechanisms involved in CCL5 secretion by the tumor cells.

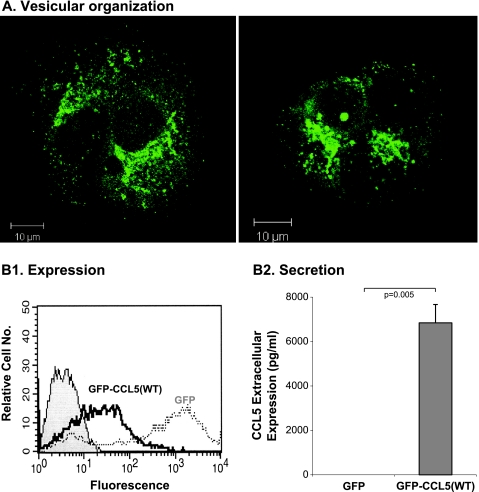

Being a secretory protein expressing a signal peptide, we have shown in our published study that endogenous CCL5 is organized in vesicles in MCF-7 breast tumor cells and is secreted by breast tumor cells in an ER-to-Golgi-dependent process [27]. In the present study, we show similar characteristics for the GFP-tagged CCL5 that we have produced, analyzed in MCF-7 cells (Figures 1 and 2). The results in Figure 1A demonstrate that the GFP-tagged chemokine had a pronounced vesicular organization, with high propensity to Golgi localization, as was confirmed in colocalization analyses described below. This pattern of intra-cellular localization also applied to CCL5 labeled by a smaller tag, when we used HA-tagged CCL5(WT), showing vesicular organization and distribution typical of Golgi (Figure W1).

Figure 1.

CCL5 is organized in vesicles and is secreted by breast tumor cells. Human MCF-7 breast tumor cells were transiently transfected by a vector expressing GFP-CCL5(WT) or by a control vector expressing GFP only (=GFP). (A) GFP-CCL5(WT) acquires a vesicular distribution in the tumor cells, as determined by confocal analysis (similar localization pattern was observed for HA-tagged WT CCL5, as shown in Figure W1). This vesicular distribution is similar to that of endogenous CCL5 produced by the cells [27]. Live cell imaging of motility of GFP-CCL5(WT)-containing vesicles is demonstrated in Video W1. The control empty vector expressing GFP had a diffuse nonorganized distribution in the cells (data not shown). (B) Determination of transfection yields and of CCL5 secretion by MCF-7 cells transfected with the GFP-CCL5(WT) vector and by the control GFP vector. (B1) Transfection yields based on GFP expression in FACS analysis. (B2) CCL5 secretion to the cell supernatants, determined by ELISA assays with antibodies against human CCL5, as described in procedure 1 in Materials and Methods. In each part of the figure, the results are representatives of at least n = 3.

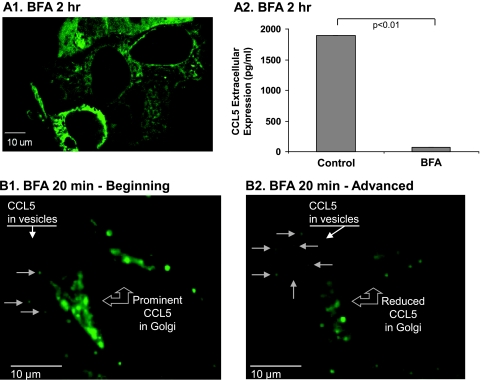

Figure 2.

Vesicles containing CCL5 are shuttled from the ER to the post-Golgi stage. The effects of treatment by BFA on the intracellular organization of vesicles containing GFP-CCL5(WT) and on CCL5 secretion. Control cells were treated by the solubilizer of the drug. (A) Human MCF-7 breast tumor cells were transiently transfected by a vector expressing GFP-CCL5(WT), and the pool of cells was split to cells treated by BFA or to control cells treated by the solubilizer of the drug. The drug did not affect cell viability (data not shown). (A1) Confocal analysis showing cells treated by BFA for 2 hours. Before BFA addition, the localization of GFP-CCL5(WT) was as in Figure 1A (vesicular and punctuate; data not shown). The picture is a representative of multiple cells analyzed in n = 2. (B) ELISA analysis of CCL5 amounts in supernatants of cells untreated or treated by BFA (for 2–5 hours, as described in Materials and Methods). The results are similar to those obtained for the endogenous CCL5 produced by breast tumor cells, shown to be mobilized toward secretion in an ER-to-Golgi-dependent manner [27]. CCL5 secretion to the cell supernatants was determined by ELISA assays with antibodies against human CCL5, as described in procedure 1 in Materials and Methods. (B) The effect of short-term treatment by BFA (20 minutes) on motility of CCL5-containing vesicles. Human MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected by GFP-CCL5(WT), and the motility of CCL5-containing vesicles was determined by live cell imaging in spinning disk confocal microscope after the treatment by BFA. The figure provides static pictures of Video W2. (B1) At the beginning of the BFA treatment, prominent localization of CCL5 was detected in the Golgi, and the chemokine was also found in peripheral vesicles. (B2) At advanced stages after this short treatment by BFA, there was almost an entire collapse of the Golgi, CCL5 was minimally detected in the Golgi, but it was still vastly localized in peripheral vesicles. The pictures are representatives of multiple cells analyzed in n ≥ 2.

Using the GFP-tagged CCL5 in our further analyses, we found that CCL5-containing vesicles had a very dynamic motility in the cells (Video W1). As expected, owing to the transfection with GFP-CCL5 (WT) (Figure 1B1), high levels of the chemokine were detected in the supernatants of the cells (Figure 1B2). The transfection of the cells by GFP-tagged empty vector (named GFP) allowed us to determine the background levels of endogenous CCL5 released by the cells. In most analyses included in the study (see below), it was difficult to detect the endogenous chemokine after transfection of the cells by GFP (as is the case in Figure 1B2). Please note that the MCF-7 cells used in this analysis, before their transfection by vector expressing GFP-CCL5(WT), release endogenous CCL5 [24,27,31], but in lower levels than the nanogram amounts released after the expression of the transfected WT chemokine. Therefore, the endogenous CCL5 is hardly detected under the current experimental conditions, designed to provide reliable detection curves of high nanogram CCL5 levels.

After these analyses that have verified the secretion of the GFP-tagged CCL5, we asked if the chemokine is released by the tumor cells in an ER-to-Golgi-dependent process, as was shown to be the case in our previous study of endogenous CCL5 in breast tumor cells. In that published investigation [27], we have shown that BFA, a drug that induces the collapse of the Golgi apparatus and blocks the transport of proteins from the ER to the trans-Golgi network [37,38], has led to a pronounced inhibition of secretion of endogenous CCL5 by the tumor cells. In line with those findings on the endogenous chemokine, when GFP-CCL5(WT)-transfected tumor cells were treated with BFA (2–5 hours; see Materials and Methods), GFP-CCL5(WT) assumed a reticulate pattern with an enhanced localization to the nuclear membrane, typical of ER localization (Figure 2A1), and almost complete inhibition of CCL5 secretion was obtained (Figure 2A2). This observation indicated that the secretion of the GFP-tagged CCL5 that we have produced, similarly to that of the endogenous CCL5 [27], requires ER-to-Golgi trafficking.

Also, in our published study, we have shown that endogenously expressed CCL5 is secreted from pre made vesicles, localized to the cell periphery [27]. To confirm the presence of such a secretion-ready vesicle population and to extend our understanding of the mechanisms involved in CCL5 secretion, we used a relatively short BFA treatment (20 minutes) designed to induce the collapse of the Golgi without affecting the vesicle population that has already reached the post-Golgi stage close to the cell periphery. Video W2, provided as static pictures in Figure 2, B1 and B2, shows by live cell imaging that despite the collapse of the Golgi, CCL5 was still localized to motile vesicles, in accord with its localization to a post-Golgi secretory compartment adjacent to the cell membrane.

Overall, the above findings validate the suitability of the GFP-tagged CCL5 for further research and are in line with our published results [27]. In addition, these results provide additional insights into basic events taking place in the course of CCL5 secretion, showing that CCL5-containing vesicles mobilize in a dynamic manner from the ER to the post-Golgi stage and give rise to a productive process of CCL5 secretion to the cell exterior.

Vesicles Containing CCL5 Move on Structured Microtubule Tracks, and the Release of the Chemokine Is Regulated by the Rigidity of the Actin Cytoskeleton

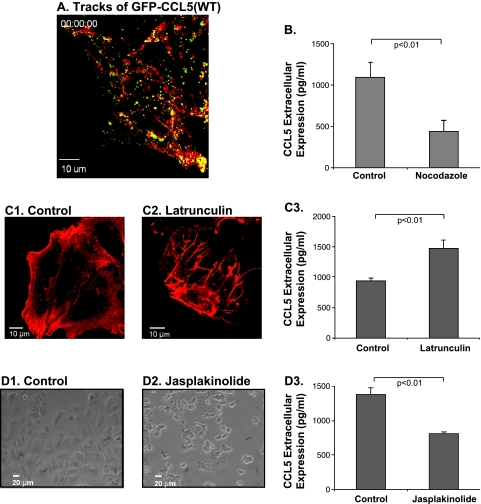

The observations obtained in the previous part of the study demonstrated a dynamic behavior of vesicles containing GFP-CCL5(WT), along well-structured paths in the cells (Video W1). To envision the tracks undertaken by the vesicles and to understand if the same paths were reused over time, we projected and pseudocolored in red the maximum intensity of the GFP signal of individual frames and superimposed this signal on the original time-lapse series. Video W3, provided as a static picture in Figure 3A, clearly shows that the vesicles containing GFP-CCL5(WT) (yellow, owing to the superimposition of the red signal of the tracks and the green signal of GFP-CCL5(WT)) traffic along structured, defined, and extended routes, which stretch throughout the cells (shown in red).

Figure 3.

The trafficking and secretion of CCL5 are regulated by cytoskeleton elements. The characteristics of CCL5 trafficking and secretion were determined in human MCF-7 breast tumor cells, transiently transfected by a vector expressing GFP-CCL5(WT). (A) GFP-CCL5(WT)-containing vesicles traffic on structured cellular tracks. The cells were imaged by live cell imaging in confocal microscopy. The figure shows a static picture of Video W3. To visualize the paths taken by moving GFP-CCL5(WT)-containing vesicles, images were projected in two dimensions using the maximum-value-per-pixel algorithm of Slidebook. The two-dimensional algorithm was pseudocolored in red and expended through the entire time-lapse series. The tracks used by GFP-CCL5(WT)-containing vesicles are demonstrated in red, and the vesicles containing GFP-CCL5(WT) (green) are shown in yellow, owing to the superimposition of red and green signals. The pictures are representatives of multiple cells analyzed in n = 2. (B, C, D) The roles of microtubules (B) and of actin filaments (C, D) in regulating the motility of CCL5-containing vesicles and the secretion of CCL5 were determined in MCF-7 cells. After transient transfection with a vector expressing GFP-CCL5(WT), the pool of cells was split to cells treated with (B) nocodazole (microtubule depolymerizing), (C) latrunculin (actin depolymerizing), or (D) jasplakinolide (actin polymerizing) and to control cells that were treated by the solubilizers of the drugs. The drugs did not affect cell viability (data not shown). (B) CCL5 secretion after treatment by nocodazole was determined as indicated below. In parallel, the motility of vesicles containing GFP-CCL5(WT) was followed by live cell imaging in confocal microscopy, without (Video W4) and following nocodazole treatment (Video W5). (C) The effects of latrunculin on the organization of actin filaments were determined by staining control cells (C1) or latrunculin-treated cells (C2) with phalloidin. (C3) CCL5 secretion after latrunculin treatment was determined as indicated below. (D) The effects of jasplakinolide on the shape and contour of the cells were determined by light microscope in control cells (D1) and in jasplakinolide-treated cells (D2). (D3) CCL5 secretion after jasplakinolide treatment was determined as indicated below. (B, C3, D3) CCL5 secretion to the cell supernatants was determined by ELISA analyses with antibodies against human CCL5, as described in procedure 1 in the Materials and Methods. In all parts of the figure, the ELISA analyses are of a representative experiment of n = 3, and the pictures are representatives of multiple cells analyzed in n = 3 (except for the live cell imaging in B, where n = 2).

Because vesicles containing GFP-CCL5(WT) had apparent directional motility and they reused defined paths, we tested the possibility that vesicles carrying the chemokine move along cytoskeleton filaments. Depolymerization of microtubules by nocodazole [39] reduced considerably the motility of CCL5-containing vesicles, and decelerated their movement along well-defined paths (Video W4: before nocodazole treatment; Video W5: after nocodazole treatment). In parallel, depolymerization of the microtubules significantly inhibited CCL5 secretion by the tumor cells (Figure 3B), being in line with the above findings showing that the inclusion of CCL5 into motile vesicles is important for its secretion (Video W1 and Figure 2).

In addition, we have analyzed the roles of the actin cytoskeleton in regulating the secretion of CCL5 by the tumor cells. After depolymerization of the actin filaments by latrunculin [40] (Figure 3, C1 and C2), the secretion of CCL5 was promoted (Figure 3C3), suggesting that the membrane-proximal actin cortex acts as a partial barrier that prevents maximal vesicle fusion and secretion of the chemokine. This possibility was supported by taking the opposite approach, in which the cells were treated by the actin polymerizing agent jasplakinolide [41]. This drug has led to change in cell shape and contour that are consistent with increased rigidity of the actin cortex (Figure 3, D1 and D2) and inhibited the secretion of CCL5 by the tumor cells (Figure 3D3).

Together, the above observations indicate that microtubules serve as structured tracks along which the chemokine-containing vesicles shuttle toward secretion, whereas the actin cytoskeleton controls the extent of chemokine release to the extracellular milieu of the cells.

The 43TRKN46 Sequence of CCL5 Is Essential for Its Secretion by Breast Tumor Cells and for Its Inclusion in Motile Vesicles

Next, we asked what are the chemokine motifs that are essential for its release by breast tumor cells and chose to focus on the 43TRKN46 sequence located in the 40s loop of CCL5. The rationale for focusing on this motif was based on the following two observations: 1) A recent study by El Golli et al. [42] has shown that the 45LKNG48 sequence of CXCL4 facilitates the targeting of this chemokine to granules in platelets. That research has suggested that the 45LKNG48 sequence of CXCL4 exhibits the same surface-exposed hydrophilic turn/loop features as the 43TRKN46 sequence of CCL5, thus motivating us to ask whether the 43TRKN46 sequence of CCL5 regulates its secretion by breast tumor cells. 2) The 43TRKN46 sequence is found in the exposed 40s loop of CCL5, known to be important for CCL5 binding to GAG and to the CCL5 receptors CCR1 and CCR3 [33,43,44]. Therefore, we speculated that such a region may mediate the interactions of the chemokine with intracellular components that shuttle it toward secretion.

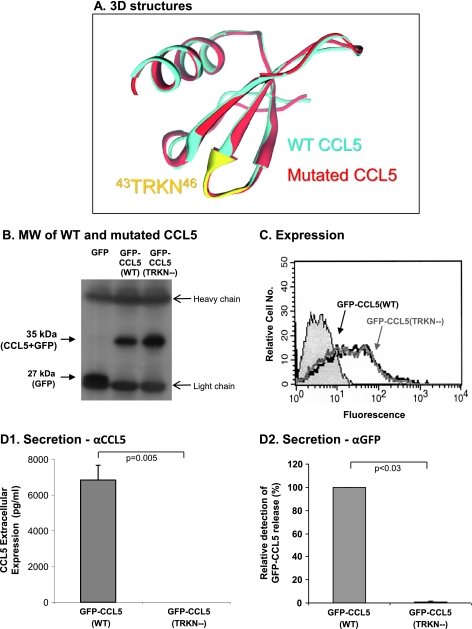

On the basis of the above, we asked if the 43TRKN46 motif of CCL5 is required for the secretion of the chemokine by breast tumor cells. To this end, we generated a CCL5(TRKN-) variant in which the 43TRKN46 motif was mutated to alanines. To guarantee that the TRKN-mutated chemokine is correctly folded, we have performed the following two analyses: 1) We determined the predicted three-dimensional structure of the TRKN-mutated chemokine by super-imposing it on the x-ray structure of WT CCL5 [33]. This analysis has shown that the TRKN-mutated CCL5 is correctly folded (Figure 4A), and this conclusion is supported by past studies showing that CCL5 mutated at 44RKNR47 (a sequence shifted one amino acid from our 43TRKN46 motif) had similar x-ray characteristics to WT CCL5 [33]. 2) Further below in the article, we describe studies determining the intracellular localization of GFP-CCL5(WT) and GFP-CCL5 (TRKN-). In those experiments (see below), we found that the mutated CCL5 exited from the ER to the Golgi, a process that could not have taken place if the mutated chemokine was misfolded owing to ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) that ensures that only properly folded and assembled proteins proceed to the Golgi for further processing and secretion [45–47].

Figure 4.

The 43TRKN46 motif of CCL5 is essential for its secretion by breast tumor cells. (A) The predicted three-dimensional structure of 43TRKN46-mutated CCL5, superimposed on the three-dimensional structure of WT CCL5 obtained by x-ray analyses [33]. Of note, this article also showed similar x-ray structures for WT CCL5 and the 44RKNR47 CCL5 mutant. (B) Human MCF-7 breast tumor cells were transiently transfected by vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT), GFP-CCL5(TRKN-), or GFP alone (GFP), followed by determination of chemokine expression in cell lysates. The chemokines were immunoprecipitated by mAb against GFP, and Western blot analysis was performed with mAb against GFP. The results are of a representative experiment of n > 3. (C, D) The effects of the 43TRKN46 mutation on CCL5 secretion. Human MCF-7 breast tumor cells were transiently transfected by vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT) or GFP-CCL5 (TRKN-), followed by determination of chemokine secretion. (C) FACS analyses showing the transfection yields of vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT) or GFP-CCL5(TRKN-). (D) Determination of CCL5 secretion to cell supernatants, performed by ELISA assays. (D1) ELISA assays with antibodies against human CCL5, as described in procedure 1 in Materials and Methods. (D2) ELISA assays with antibodies against human GFP, as described in procedure 2 in Materials and Methods. The results in all parts of the figure are of a representative experiment of n > 3. Additional ELISA analyses with other combinations of antibodies, showing the reduced secretion of GFP-CCL5 (TRKN-), are provided in Figure W2.

We now asked if the vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT) and GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) generate proteins at the correct molecular weights (MWs). Western blot analyses performed on cell lysates of cells transfected with GFP-CCL5(WT) and with GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) have shown that the two proteins had a similar MW, and they both assumed the expected MW of 35 kDa, as expected for CCL5 tagged by GFP (CCL5, ∼8 kDa; GFP, ∼27 kDa) (Figure 4B).

After these analyses, we have determined the secretion of GFP-CCL5(WT) and GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) by the tumor cells. Figure 4C shows that the transfection yields of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) were very similar to those of GFP-CCL5(WT) in the tumor cells. However, whereas the WT chemokine was highly secreted and was detected in high levels in the cell supernatants, very substantial inhibition of secretion was obtained for the mutated GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) (Figure 4, D1 and D2). This was indicated by ELISAs performed with antibodies against CCL5 (Figure 4D1) and with antibodies against the GFP tag (Figure 4D2). Very prominent reduction in the secretion of the GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) was obtained also by two additional ELISA analyses performed with other combinations of antibodies (Figure W2).

In line with the perturbed secret ion of the mutated GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) by the tumor cells, we found that the mutated chemokine had a diffuse/reticulate distribution, with no definite vesicular organization (Figures 5 and 6). Live cell imaging experiments have shown that the motility of the mutated chemokine was limited, random, and nondirectional (Video W6), in contrast to the dynamic and directional motility of vesicles containing GFP-CCL5(WT) (Video W1). These findings, showing lack of vesicular localization of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-), support fully the prominent reduction observed in secretion of the mutated chemokine by the tumor cells.

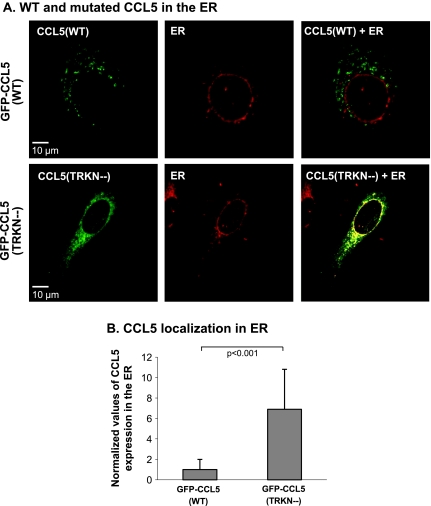

Figure 5.

GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) is found in the ER in higher propensity than GFP-CCL5(WT). Confocal pictures showing the localization pattern of GFP-CCL5(WT) and of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) with the ER marker calnexin. (A) Human MCF-7 breast tumor cells were transiently transfected by vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT) or GFP-CCL5(TRKN-). The colocalization of CCL5 (green) with an ER marker (calnexin, red) was determined by confocal analysis and shown in orange/yellow. The pictures also show that, in contrast to the vesicular organization of GFP-CCL5(WT), the GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) had a diffuse/reticulate organization. The nondirectional and limited motility of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) in the tumor cells is shown in Video W6. The pictures are representatives of multiple cells analyzed in n > 3. (B) Quantitative analysis of the colocalization of the mutated and GFP-CCL5(WT) molecules with calnexin, performed on a large number of cells. The graph shows the mean ± SD of the normalized values obtained in n = 3. P values were obtained from actual values of the computational analysis before normalization.

Figure 6.

GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) reaches the Golgi apparatus but in a lower propensity than GFP-CCL5(WT). Confocal pictures showing the localization pattern of GFP-CCL5(WT) and of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) with the Golgi marker a mannosidase IB. (A) Human MCF-7 breast tumor cells were transiently transfected by vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT) or GFP-CCL5(TRKN-). The colocalization of CCL5 (green) with a Golgi marker (a mannosidase IB, red) was determined by confocal analysis and is shown in orange/yellow. The pictures also show that, in contrast to the vesicular organization of GFP-CCL5(WT), the GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) had a diffuse/reticulate organization. The nondirectional and limited motility of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) in the tumor cells is shown in Video W6. The pictures are representatives of multiple cells analyzed in n > 3. (B) Quantitative analysis of the colocalization of the mutated and GFP-CCL5(WT) molecules with a mannosidase IB, performed on a large number of cells. The graph shows the mean ± SD of the normalized values obtained in n = 3. P values were obtained from actual values of the computational analysis before normalization.

The TRKN-Mutated Chemokine Reaches the Golgi, but Traffics along the ER-to-Post-Golgi Route in a Different Manner than the WT Chemokine

The above results indicate that the 43TRKN46 motif of CCL5 is essential for the vesicular organization and for the secretion of the chemokine by breast tumor cells. To provide further insights to the mechanisms responsible for reduced secretion of the TRKN-mutated CCL5, we have determined its intracellular localization along the ER-to-Golgi trafficking process, relative to the WT chemokine. To this end, we studied the colocalization of the WT CCL5 or mutated CCL5 chemokines with markers of the ER (calnexin) and of the Golgi (ε mannosidase IB). The extent of colocalization was also determined quantitatively, as described in Materials and Methods.

The results in Figures 5 and 6 indicate that the GFP-CCL5 (TRKN-) exited from the ER to the Golgi, however, with modified proportions compared to the WT chemokine. The TRKN-mutated chemokine had higher propensity for ER localization than the WT chemokine (Figure 5), and in parallel, its expression in the Golgi was somewhat reduced (Figure 6). These results indicate that: 1) The 43TRKN46 motif regulates the trafficking of CCL5 at two points along the mobilization process, where the first stage takes place at the exit from the ER to the trans-Golgi network and the second is in trafficking of CCL5, in motile vesicles at the post-Golgi stage, a stage that is required for completion of secretion. These findings agree well with the reduced secretion of the TRKN-mutated CCL5 by the tumor cells. 2) GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) exited from the ER and reached the Golgi, indicating that it is correctly folded because its inappropriate folding would have led to activation of the ERAD process [45–47] that would have completely prevented its exit from the ER.

The 43TRKN46 Sequence Is a Ubiquitous Motif Required for Secretion of CCL5 in Many Different Cell Types

In our search for the mechanisms that may be involved in the 43TRKN46-mediated process of CCL5 secretion, we first asked if the dependence on the 43TRKN46 motif is a general phenomenon shared by many cell types or whether it is specific to breast tumor cells in general, or to MCF-7 cells in particular. To answer this question, we have expressed GFP-CCL5(WT) and GFP-CCL5(TRKN-), which were compared with control GFP vector, in several cell types. In each of the cell types, we validated that the expression levels of GFP-CCL5(WT) were similar to those of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-)(Figure 7, A1–D1) and determined the release of the WT or the mutated CCL5 by the cells (Figure 7, A2–D2; please note that the levels of chemokines are presented in different scales in the various panels of the figure).

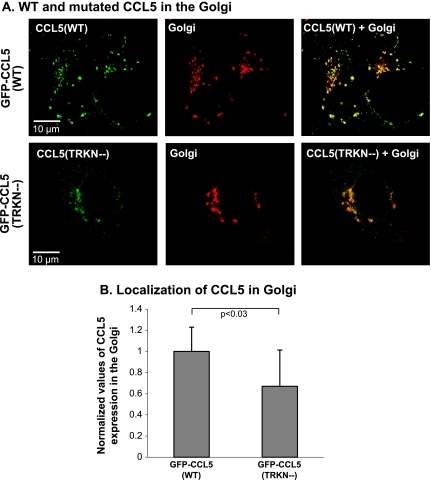

Figure 7.

The 43TRKN46 sequence is required for CCL5 secretion in many cell types. Different cell types were transiently transfected by vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT), GFP-CCL5(TRKN-), or GFP alone (GFP) (please note the different scales used for the various cell types in the ELISA analyses presented). (A1–D1) FACS analyses showing the transfection yields of GFP-CCL5(WT) and GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) in the different cell types. (A2–D2) The secretion of CCL5 was determined by ELISA assays, performed on cell supernatants of the different cell types, with antibodies against human CCL5, as described in procedure 1 in the Materials and Methods. (A1, A2) Human T47D nonaggressive breast carcinoma cells. (B1, B2) Human MDA-MB-231 metastatic breast carcinoma cells. (C1, C2) Human mammary normal epithelial cells. (D1, D2) Human WI-38 normal lung fibroblasts. In all parts of the figure, the results are of a representative experiment of n = 3.

We began this analysis by studying the T47D human breast tumor cells that, like MCF-7 cells are tumorigenic but not metastatic, and the MDA-MB-231 cells that are highly metastatic human breast tumor cells [35]. In both cell types, the patterns of CCL5 release were similar to those of MCF-7 cells: GFP-CCL5(WT) was highly secreted, whereas the release of mutated CCL5 was prominently inhibited by the mutation of the 43TRKN46 motif (Figure 7, A2 and B2). This has indicated that the 43TRKN46 motif is involved in CCL5 trafficking in breast tumor cells, independently of their metastatic potential.

We then asked if the same is correct for nontransformed human cells of the breast (HMEC) and for normal human lung fibroblasts (WI-38) (Figure 7, C2 and D2). We found that also in these two cell types, the secretion of the mutated GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) chemokine was much reduced when compared with the release of GFP-CCL5(WT) by the cells. In general, reduced secretion of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) was also detected in the MCF-10A nontransformed breast epithelial cells (data are not presented because, in several of the experiments, the transfection procedure has led to very high release of endogenous CCL5 by the cells, making the expression of GFP-CCL5(WT) inefficient. In these specific cases, it was difficult to interpret the exact pattern of secretion of the mutated chemokine and to correctly appreciate what seemed to be a dominant negative effect induced by GFP-CCL5 (TRKN-)).

Taken together, the above results indicate that the 43TRKN46-dependent mechanism of CCL5 secretion is shared by many cell types and is probably ubiquitous. These observations have led us to search for a general mechanism, by which the 43TRKN46 motif is required for the secretion of CCL5.

The Process of CCL5 Secretion Is Partly Regulated by GAG

In search for a general mechanism which leads to CCL5 secretion and is shared by many cell types, we investigated the possibility that CCL5 interacts with intracellular GAG on its trafficking route toward release from the cells. This approach was based on published studies showing that GAG-decorated proteoglycans participate in the packaging of positively charged proteins in cytotoxic lymphocytes—such as granzymes and perforin [48,49]—and that supernatants of activated human immunodeficiency virus 1-specific cytotoxic t cells include CC chemokines complexed with proteoglycans [50]. The latter study did not address the involvement of GAG in the intracellular mobilization of the chemokines toward secretion, but it motivated us to determine the possibility that GAG regulate the intracellular trafficking and release of the CC chemokine CCL5 in breast tumor cells. This possibility was reinforced by the fact that the CCL5-secretory motif of 43TRKN46 is only one amino acid shifted from the 44RKNR47 sequence of CCL5, known to be essential for CCL5 binding to GAG [33,43,44]. Importantly, both43TRKN46 and 44RKNR47 express positively charged amino acids that are part of the sequence required for GAG binding [33,43,44]. Therefore, if indeed intracellular GAG are required for CCL5 secretion, it is possible that they interact with the 43TRKN46 motif of CCL5, which is essential for the release of this chemokine by the tumor cells.

On the basis of the above, our primary goal in this part of the study was to determine whether the secretion of CCL5 by breast tumor cells was regulated by intracellular GAG. To achieve this aim, we took several approaches in which we determined the effects of GAG inhibition on the secretion of WT CCL5. In the framework of this study, we have also addressed indirectly the possibility that the 43TRKN46 motif associates with such intracellular GAG. This point was not addressed by direct measures because of two restrictions: 1) We found that, because of technical reasons, it is impossible to isolate from the transfected cells the actual molecules of GFP-CCL5(WT) and of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) in a manner that will enable determination of their binding to GAG on solid surfaces (plates or beads). 2) The approach of CCL5 immunoprecipitation with GAG was expected to be problematic owing to the weak nature of the chemical bonds between them.

Below we provide data on the analyses that we have performed to address the roles of intracellular GAG in CCL5 secretion and the measures taken to address the possible involvement of the CCL5 43TRKN46 sequence in such a GAG-mediated process. The findings provided below indicate that intracellular GAG are indeed involved in CCL5 secretion. In parallel, our findings are suggestive of a process in which the 43TRKN46 motif of CCL5 participates in a mechanism mediated by GAG, and this possibility is supported by additional findings in the literature, as detailed in the Discussion section.

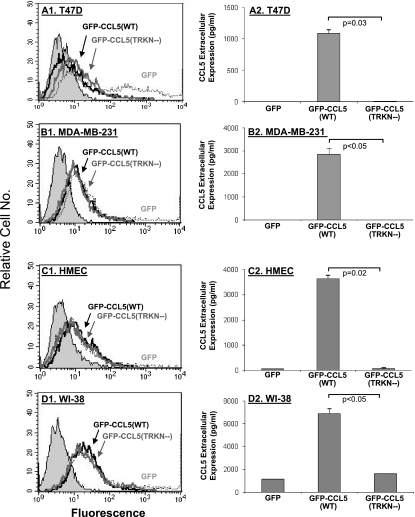

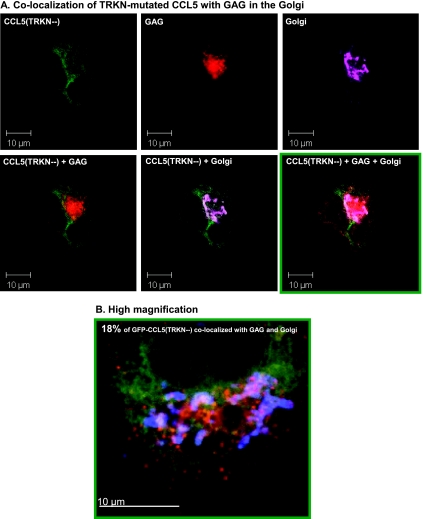

First, we asked if the TRKN-mutated CCL5 diverges from the WT chemokine in its ability to associate with GAG in the Golgi. This approach was based on our findings showing that the secretion of WT CCL5 requires positioning of the chemokine in the Golgi (Figure 2 and [27]) and that, in the Golgi, saccharides are appended to protein cores by glycosyltransferases, leading to formation of proteoglycans [51]. By performing triple-dye analyses, we have shown that GFP-CCL5(WT) was highly colocalized with GAG in the Golgi (Figure 8), whereas the mutated GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) had a considerably reduced colocalization with GAG in the Golgi (Figure 9). These data show that CCL5 is highly localized in secretion-related organelles (Golgi) that are enriched with GAG and that this localization is associated with the expression of the positively charged 43TRKN46 motif of CCL5.

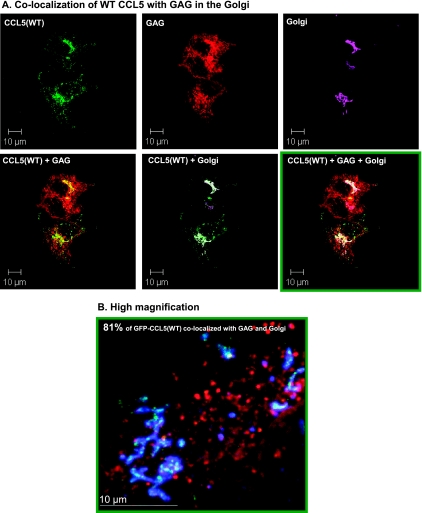

Figure 8.

The localization of GFP-CCL5(WT) with GAG in the Golgi. Human MCF-7 breast tumor cells were transiently transfected by a vector expressing GFP-CCL5(WT). The colocalization of CCL5 (green) with GAG (red), and with a Golgi marker (a mannosidase IB, purple/blue) was determined by confocal analysis. (A) The pictures show each of the proteins alone, as well as combinations of the following: GFP-CCL5(WT) + GAG, GFP-CCL5(WT) + Golgi, or GFP-CCL5(WT) + GAG + Golgi. The colocalization of GFP CCL5(WT) + GAG + Golgi is demonstrated in white. (B) Higher magnification of the colocalization of GFP-CCL5(WT) with GAG and Golgi, demonstrated in bright white. The percentage of GFP-CCL5(WT) that was colocalized with GAG and Golgi is indicated in the figure. The pictures are representatives of multiple cells analyzed in n = 3.

Figure 9.

The localization of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) with GAG in the Golgi. Human MCF-7 breast tumor cells were transiently transfected by a vector expressing GFP-CCL5(TRKN-). The colocalization of CCL5 (green) with GAG (red), and with a Golgi marker (a mannosidase IB, purple/blue) was determined by confocal analysis. (A) The pictures show each of the proteins alone, as well as combinations of the following: GFP-CCL5(TRKN-)+ GAG, GFP-CCL5(TRKN-)+ Golgi, or GFP-CCL5(TRKN-)+ GAG + Golgi. The colocalization of GFP-CCL5 (TRKN-)+ GAG + Golgi is demonstrated in white. (B) Higher magnification of the colocalization of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) with GAG and Golgi, demonstrated in bright white. The percentage of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) that was colocalized with GAG and Golgi is indicated in the figure. The pictures are representatives of multiple cells analyzed in n = 3.

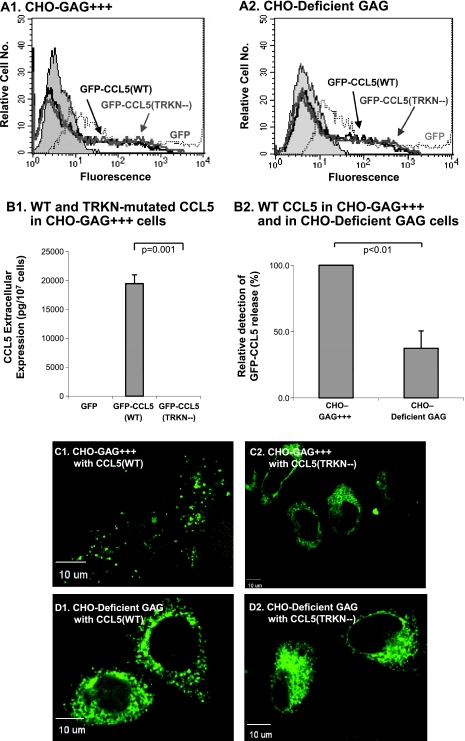

Next, we asked if GAG are required for CCL5 secretion, and to what extent. To address this issue, we have used a highly specific approach, in which we measured the degree of GFP-CCL5(WT) secretion by mutated CHO cells that have substantially reduced levels of GAG synthesis due to deficiency in xylosyltransferase, which initiates GAG biosynthesis [52]. The secretion of GFP-CCL5(WT) by these “CHO-deficient GAG” cells (original name CHO-pgsA-745 cells) was compared to “CHO-GAG+++” cells that expressed normal GAG levels (original name CHO-K1 cells). Here, it is important to indicate that 1) we ensured that the CHO-deficient GAG cells indeed did not express GAG (data not shown) and that 2) the CHO-deficient GAG cells do not have a general defect in secretion [53]; therefore, they were valid for our studies.

This analysis was begun by validating that similarly to MCF-7 cells, CHO cells that express normal levels of GAG mobilize CCL5 through the 43TRKN46 motif. Indeed, Figure 10, A and B1, shows that, despite similar transfection yields of GFP-CCL5(WT) and GFP-CCL5 (TRKN-) in the CHO-GAG+++ cells, the mutated GFP-CCL5 (TRKN-) chemokine was not secreted by the cells. Furthermore, the mutated chemokine assumed a reticulate intracellular localization in the CHO-GAG+++ cells (Figure 10C), as was the case in MCF-7 cells (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 10.

The secretion of GFP-CCL5(WT) and its vesicular organization are perturbed in CHO-deficient GAG cells. CHO cells were transfected by vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT), GFP-CCL5(TRKN-), or GFP alone (GFP), followed by determination of secretion and intracellular organization of CCL5. The analyses were performed in cells that expressed normal GAG levels, termed herein CHO-GAG+++ cells (=CHO-K1 cells), compared to CHO cells deficient in GAG expression, termed herein CHO-deficient GAG cells (=CHO-pgsA-745 cells). (A1, A2) FACS analyses showing the transfection yields of GFP-CCL5(WT) and GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) in CHO-GAG+++ cells and in CHO-deficient GAG cells. The results are of a representative experiment of n = 2–3. (B) CCL5 secretion, determined by ELISA assays performed on supernatants of the different cell types, with antibodies against human CCL5, as described in procedure 1 in Materials and Methods. (B1) Secretion of WT CCL5 in CHO-GAG+++ cells, transfected with vectors expressing GFP-CCL5(WT), GFP-CCL5(TRKN-), or GFP vector only (=GFP). The results are of a representative experiment of n = 3. (B2) Secretion of CCL5 by CHO-GAG+++ cells and by CHO-deficient GAG cells, transfected with GFP-CCL5(WT). The results are mean ± SD of normalized values of CCL5 secretion in n = 3. P values were obtained from actual values of the computational analysis before normalization. (C, D) Intracellular localization of GFP-CCL5(WT) (C1, D1) and of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) (C2, D2) in CHO-GAG+++ cells (C1, C2) and in CHO-deficient GAG cells (D1, D2). In C and D, the results are of a representative experiment of n = 2, with multiple cells analyzed in each experiment.

Then, we compared the release of GFP-CCL5(WT) in CHO-GAG+++ cells to its secretion by CHO-deficient GAG cells. The results in Figure 10B2 show that the control CHO-GAG+++ cells released high levels of GFP-CCL5(WT); however, the secretion of GFP-CCL5(WT) by CHO-deficient GAG cells was prominently impaired, although only partly. The CHO-deficient GAG cells also failed to release the mutated CCL5, as was the case in the other cell lines that were investigated (data not shown).

Further analyses that were performed in the CHO-deficient GAG cells have indicated that GAG are important not only for the secretion of GFP-CCL5(WT) but also for its vesicular localization. Figure 10C1 shows that in CHO-GAG+++ cells, GFP-CCL5(WT) was localized in vesicles that had a very definite punctuate distribution. In contrast, in CHO-deficient GAG cells, the punctuate distribution of GFP-CCL5 (WT) was perturbed (Figure 10D1), and the WT chemokine was largely localized in the ER and acquired a phenotype which was in general similar to that of the TRKN-mutated CCL5, which was expressed in normal, GAG-expressing cells (Figures 10C2, 5, and 6).

The roles of GAG in regulating the secretion of GFP-CCL5(WT) was further supported by three additional methods taken to inhibit GAG presence or synthesis in the cells. These experiments were performed in the original MCF-7 breast tumor cells, in which the secretion of the GFP-CCL5(WT) was analyzed with and without different GAG inhibitory measures. We did not analyze the effects of these measures on the mutated chemokine because it was not secreted by the MCF-7 cells, as shown in Figure 4. In all three types of analysis, we have ensured similar expression of the GFP-CCL5(WT) in cells not treated, compared with cells treated by the different inhibitory measures (see the relevant figures, as indicated herein).

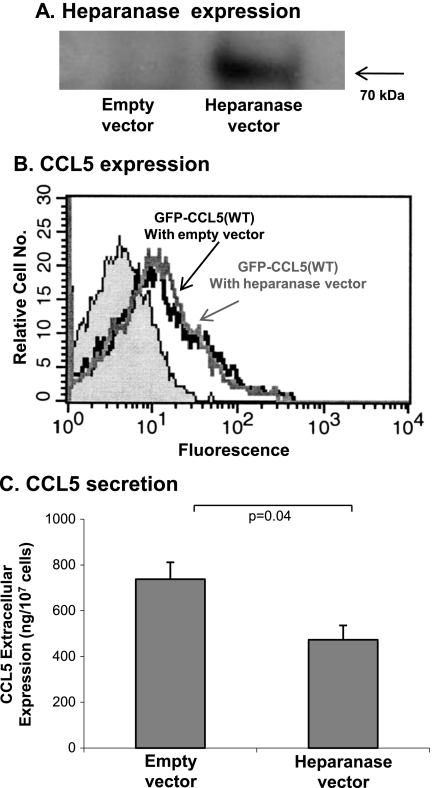

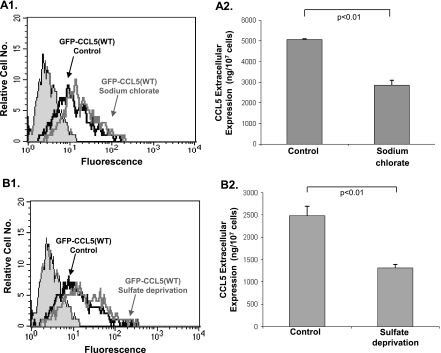

The following three methods were applied to inhibit GAG functions in the tumor cells: 1) We have expressed in breast tumor cells heparanase (Figure 11), an enzyme that degrades heparane sulfate, which is one of the GAG that bind CCL5 [44,54–56]. The results in Figure 11A show that heparanase was expressed intracellularly in the tumor cells, at the expected MW for the intracellularly expressed enzyme, tagged by myc (∼65 kDa of heparanase [57] + the myc tag). In cells expressing the enzyme intracellularly, the secretion of GFP-CCL5(WT) was significantly inhibited, compared to control cells transfected by vector only. However, the reduction in CCL5 secretion after expression of heparanase was only partial (Figure 11, B and C). 2) In view of the importance of GAG sulfation for binding of chemokines, including of CCL5 [33,58–60], we treated the cells with sodium chlorate, a competitive inhibitor of ATP-sulfurylase that inhibits the sulfation process of GAG and is used routinely as a measure for reduction of GAG sulfation, including in aspects related to chemokine activities [61–63]. This treatment has also led to significant, but partial, reduction in secretion of CCL5 by the tumor cells (Figure 12A). 3) We have deprived sulfate out of the growth medium of the cells. As shown in Figure 12B, this measure has also led to significant inhibition of GFP-CCL5(WT) secretion by the cells. Here again, the reduction was partial. The combination of the sodium chlorate treatment + sulfate deprivation did not yield additive inhibitory effects on the secretion of GFP-CCL5(WT) by the tumor cells, and the inhibition level remained partial (data not shown). These results indicate that the involvement of GAG activities has reached a saturation point, with respect to their roles in regulating CCL5 secretion.

Figure 11.

Intracellular expression of heparanase leads to reduced secretion of GFP-CCL5(WT) by breast tumor cells. Human MCF-7 breast tumor cells were transiently transfected by a vector expressing GFP-CCL5(WT). In parallel, the cells were transfected with a myc-tagged vector expressing heparanase or by a control myc-tagged empty vector. (A) Western blot showing the expression of heparanase in cells transfected with heparanase-containing vector but not in cells transfected with the control vector. The analysis was performed with antibodies against myc. The MW of the heparanase is the one expected for the intracellularly expressed enzyme, tagged by myc (∼65 kDa of heparanase + the myc tag). No signal was detected in the control cells transfected with the myc-tagged vector only because of its small MW (in the conditions used for appropriate detection of the heparanase, the myc protein run out of the gel). (B) FACS analysis showing the transfection yields of GFP-CCL5(WT) in cells transfected with the heparanase vector and those transfected with control vector. (C) CCL5 secretion to the cell supernatants determined by ELISA assays with antibodies against human CCL5, as described in procedure 1 in Materials and Methods. In all parts of the figure, the results are of a representative experiment of n > 3.

Figure 12.

The secretion of GFP-CCL5(WT) by breast tumor cells is inhibited by reduced sulfation of GAG. The effects of GAG undersulfation on the secretion of CCL5 were determined in MCF-7 cells, transfected with GFP-CCL5(WT). (A) Treatment by sodium chlorate, a competitive inhibitor of ATP-sulfurylase that inhibits the sulfation process of GAG (30 mM, 48 hours). (B) The cells were exposed to sulfate deprivation by growth in sulfate-deficient medium (48 hours). (A1, B1) FACS analyses showing the transfection yields of GFP-CCL5(WT) in control cells and in cells in which undersulfation was induced by (A1) sodium chlorate or (B1) sulfate deprivation. (A2, B2) The secretion of CCL5 was determined by ELISA assays, performed on supernatants of control cells and of cells in which undersulfation was induced, performed with antibodies against human CCL5, as described in procedure 1 in Materials and Methods. (A2) Sodium chlorate. (B2) Sulfate deprivation. In all parts of the figure, the results are of a representative experiment of n = 3.

To conclude, by taking four different inhibitory approaches, we have shown that GAG play a significant and an important role in mobilizing GFP-CCL5(WT) toward secretion. However, these GAG-inhibitory measures have led to only partial reduction in secretion of GFP-CCL5(WT), suggesting that other mechanisms regulate CCL5 release as well. Our results show that GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) had reduced localization with GAG in the Golgi and that GFP-CCL5(WT) had an ER-like organization in GAG-deficient cells, which was similar to the organization of the TRKN-mutated chemokine in GAG-expressing cells. Together with supporting findings in the literature (see Discussion), it is possible that one of the mechanisms mediating CCL5 secretion is a process involving 43TRKN46-GAG associations.

Discussion

The results of this study provide novel information on the molecular mechanisms involved in the secretion of CCL5. They are the first to identify a role for the 40s loop of CCL5 and for GAG in trafficking and secretion of this chemokine. These findings contribute to our understanding of basic processes controlling the expression of promalignancy chemokines in tumor cells and may have potential therapeutic implications, as follows:

The 43TRKN46 Motif Is Essential for CCL5 Secretion and for Its Inclusion in Motile Vesicles

The results of this study indicate that the secretion of a TRKN-mutated CCL5 by breast tumor cells is prominently reduced and that the 43TRKN46 sequence is a ubiquitous motif required for the secretion of the chemokine by many cell types. Additional analyses that we have performed (article in preparation) indicate that the TRKN sequence requires the backbone of CCL5 to act as a secretion-determining motif because it did not support the secretion of a different chemokine when it was positioned at its 40s domain (data not shown). The need for the 40s domain of a chemokine for its secretion is supported by recent findings showing that regions of the 40s loop regulate the sorting of the chemokine CXCL4 (45LKNG48) into a granules in platelets and of CXCL8 (44DSG46) into Weibel-Palade bodies in endothelial cells [42,64].

Our confocal analyses identified a defect in the intracellular organization and in the ability of the mutated chemokine to use the appropriate routes on its way toward secretion. Whereas the WT chemokine was mobilized from the ER to the post-Golgi stage and was organized in vesicles that moved on definite microtubule tracks, the TRKN-mutated chemokine was loosely organized in diffuse vesicles that had random, unstructured, and limited motility in the cells.

Furthermore, our findings indicate that the 43TRKN46 motif of CCL5 regulates the trafficking of the chemokine at two points of the ER-to-post-Golgi path: Some of the molecules of the TRKN-mutated chemokine could not find their way to the Golgi, and those that did reach the Golgi could not give rise to a productive release of the chemokine to the cell exterior. The fact that a considerable amount of GFP-CCL5(TRKN-) molecules did exit from the ER to the Golgi indicates that the folding of the mutated chemokine is correct; otherwise, the ERAD process [45–47] would have led to complete arrest of their exit from the ER.

Secretion of CCL5 Is Partly Regulated by a GAG-Dependent Process

We have shown by four different approaches that GAG are necessary and important for CCL5 secretion. These approaches included three highly specific methods: one based on GAG-mutated CHO cells, the second on the use of the enzyme heparanase that degrades heparane sulfate, and the third on perturbation of GAG sulfation by a competitive inhibitor of ATP-sulfurylase. The results of these studies were reinforced by sulfate deprivation. Furthermore, our results with heparanase provided a partial clue to the identity of the GAG involved in this process, suggesting that heparane sulfate participates in the release of CCL5 by the cells.

On the basis of the above, we propose that one of the mechanisms mediating CCL5 secretion is based on the ability of CCL5 to “hitch-hike” on GAG, possibly on GAG-decorated proteoglycans, that make their way to the cell membrane or to the cell exterior. Supporting this mechanism are two recent studies, one by Meen et al. [65] that suggested that a proteoglycan-mediated process was involved in the secretion of the chemokine CXCL1 by endothelial cells and the second on FGF-2, showing that extracellular heparane sulfate proteoglycans formed a molecular trap that translocated the protein across the plasma membrane [66].

It is interesting to note that all four measures that were taken in our study to reduce GAG activities/expression were in good agreement with each other, all yielding similar inhibition levels of CCL5 secretion, between 40% and 60%. It is possible that the presence or synthesis of GAG was not completely shut down by any of these measures; however, as indicated in the Results section, when sulfate deprivation was combined with sodium chlorate, there was no additive inhibitory effect, and the inhibition of CCL5 secretion remained partial (data not shown).

Therefore, it is very likely that the partial reduction in CCL5 secretion, which was obtained by the different measures of GAG inhibition, actually reflects the existence of alternative mechanisms that are involved in CCL5 secretion. Because the absence of the 43TRKN46 motif has led to complete inhibition of CCL5 secretion whereas the degree of GAG involvement in CCL5 secretion was only partial, such additional mechanisms possibly also regulate the secretion of CCL5 in a 43TRKN46-dependent manner. On the basis of the literature, we speculate that one such additional mechanism may be based on CCR1 and CCR3, at least in breast tumor cells, because these cells express such receptors [7,19]. This possibility is supported by the fact that the 44RKNR47 sequence mediates the binding of CCL5 to CCR1 and CCR3 [43,44]. These findings stand in the basis of our plans to investigate whether CCR1 and CCR3 regulate the release of CCL5 in breast tumor cells.

Taking our novel findings a step further and considering them with additional results provided in our study and in the literature, it is logical to assume that the secretion of CCL5 by breast tumor cells is regulated by associations formed through its 43TRKN46 motif with GAG. This possibility is supported by the following observations: 1) In contrast to WT CCL5 that had a definite colocalization with GAG in the Golgi, the TRKN-mutated chemokine had much lower propensity to such colocalization. These findings indicate that the existence of the positively charged 43TRKN46 motif of CCL5 is associated with the localization of the chemokine in GAG-enriched secretion-related organelles (Golgi) and supports the role of 43TRKN46-GAG associations in the secretion of CCL5. 2) Our confocal analyses have shown that WT CCL5 acquired a reticulate localization phenotype, which is typical of ER, in CHO-deficient GAG cells, similar to the one detected for the TRKN-mutated chemokine in normal GAG expressing cells. This observation suggests that the organization of CCL5 in the Golgi is mediated through the 43TRKN46 motif. 3) Our secretion-regulating 43TRKN46 sequence carries two of the three basic residues found in the 44RKNR47 motif, that is essential for CCL5 binding to GAG [33,43,44,60]. 4) Being a CC chemokine, CCL5 was found to be expressed in supernatants of human immunodeficiency virus-specific cytolytic T cells in complexes with proteoglycans [50]. Our study suggests that the reason for CCL5 association with proteoglycans in the extracellular milieu of those cells is that the chemokine associated with them intracellularly on its path toward secretion and that this process involved a 43TRKN46-GAG-mediated mechanism.

From the therapeutic point of view, the identification of the components that regulate the secretion of CCL5 may have potential implications, as they may pave the way toward the future design of modalities that inhibit 43TRKN46-mediated or GAG-mediated mechanisms, leading thereafter to reduced release of CCL5 by breast tumor cells. Moreover, the fact that the 43TRKN46 motif is required for the secretion of CCL5 by many cell types (Figure 7) suggests that the different measures taken to reduce the 43TRKN46-mediated process of CCL5 secretion may inhibit the release of the chemokine also by tumor-promoting host cells that are found at the tumor microenvironment, like leukocytes or mesenchymal stem cells, that contribute to tumor growth through CCL5 release [13,24].

Although such an approach may lead to inhibition of CCL5 secretion also at inflammatory sites, it is not expected to impose a threat on the immune integrity of the host because the immune activities of CCL5 are backed up by other chemokines [67,68]. One additional aspect of inhibitory modalities that target the 43TRKN46-mediated or GAG-mediated mechanism is the question whether they would lead also to reduced secretion of other chemokines or to interference with their binding to GAG in other cell types. The interactions of many chemokines with GAG are mediated by basic amino acids of the chemokines and negative charges of the GAG molecules. However, the different chemokines diverge in the sequences through which they bind to GAG and in the positions of such domains in the chemokine sequence. Hence, it is possible that the secretion of other chemokines would not be affected when the 43TRKN46-mediated or GAG-mediated trafficking of CCL5 is targeted and inhibited.

To conclude, our study has provided novel findings on the regulatory processes involved in the secretion of CCL5 by breast tumor cells and are the first to identify the important roles played by the 40s loop of CCL5 and of GAG in the secretion of this chemokine. In our future studies, we will aim at targeting the 43TRKN46-mediated or GAG-mediated mechanisms that lead CCL5 toward secretion and will determine the effects of such inhibitory measures on the malignancy phenotype of breast tumor cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof Vlodavsky and Dr Ilan from the Technion (Haifa, Israel) for providing the CHO cells and the heparanase constructs used in the study and Dr Barbul (Tel Aviv University) for his assistance with the confocal analyses.

Abbreviations

- BFA

brefeldin A

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

ER-associated protein degradation

- HMEC

human mammary normal epithelial cell

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MW

molecular weight

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

This study was supported by Israel Science Foundation and by Federico Foundation. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article refers to supplementary materials, which are designated by Videos W1 to W6 and Figures W1 and W2 and are available online at www.neoplasia.com.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, Garlanda C, Mantovani A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1073–1081. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagemann T, Balkwill F, Lawrence T. Inflammation and cancer: a double-edged sword. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:300–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soria G, Ben-Baruch A. The CCL5/CCR5 Axis in Cancer. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soria G, Ben-Baruch A. The inflammatory chemokines CCL2 and CCL5 in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;267:271–285. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adler EP, Lemken CA, Katchen NS, Kurt RA. A dual role for tumor-derived chemokine RANTES (CCL5) Immunol Lett. 2003;90:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azenshtein E, Luboshits G, Shina S, Neumark E, Shahbazian D, Weil M, Wigler N, Keydar I, Ben-Baruch A. The CC chemokine RANTES in breast carcinoma progression: regulation of expression and potential mechanisms of promalignant activity. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1093–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson SC, Scott KA, Wilson JL, Thompson RG, Proudfoot AE, Balkwill FR. A chemokine receptor antagonist inhibits experimental breast tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8360–8365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su X, Ye J, Hsueh EC, Zhang Y, Hoft DF, Peng G. Tumor microenvironments direct the recruitment and expansion of human TH17 cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:1630–1641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JE, Kim HS, Shin YJ, Lee CS, Won C, Lee SA, Lee JW, Kim Y, Kang JS, Ye SK, et al. LYR71, a derivative of trimeric resveratrol, inhibits tumorigenesis by blocking STAT3-mediated matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression. Exp Mol Med. 2008;40:514–522. doi: 10.3858/emm.2008.40.5.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cappellen D, Schlange T, Bauer M, Maurer F, Hynes NE. Novel c-MYC target genes mediate differential effects on cell proliferation and migration. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:70–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiao X, Katiyar S, Willmarth NE, Liu M, Ma X, Flomenberg N, Lisanti MP, Pestell RG. c-Jun induces mammary epithelial cellular invasion and breast cancer stem cell expansion. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8218–8226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.100792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, Sullivan A, Brooks MW, Bell GW, Richardson AL, Polyak K, Tubo R, Weinberg RA. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mira E, Lacalle RA, Gonzalez MA, Gomez-Mouton C, Abad JL, Bernad A, Martinez AC, Manes S. A role for chemokine receptor transactivation in growth factor signaling. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:151–156. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinilla S, Alt E, Abdul Khalek FJ, Jotzu C, Muehlberg F, Beckmann C, Song YH. Tissue resident stem cells produce CCL5 under the influence of cancer cells and thereby promote breast cancer cell invasion. Cancer Lett. 2009;284:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prest SJ, Rees RC, Murdoch C, Marshall JF, Cooper PA, Bibby M, Li G, Ali SA. Chemokines induce the cellular migration of MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cells: subpopulations of tumour cells display positive and negative chemotaxis and differential in vivo growth potentials. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1999;17:389–396. doi: 10.1023/a:1006657109866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Youngs SJ, Ali SA, Taub DD, Rees RC. Chemokines induce migrational responses in human breast carcinoma cell lines. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:257–266. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970410)71:2<257::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zabouo G, Imbert AM, Jacquemier J, Finetti P, Moreau T, Esterni B, Birnbaum D, Bertucci F, Chabannon C. CD146 expression is associated with a poor prognosis in human breast tumors and with enhanced motility in breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R1. doi: 10.1186/bcr2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Yao F, Yao X, Yi C, Tan C, Wei L, Sun S. Role of CCL5 in invasion, proliferation and proportion of CD44+/CD24- phenotype of MCF-7 cells and correlation of CCL5 and CCR5 expression with breast cancer progression. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:1113–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forst B, Hansen MT, Klingelhofer J, Moller HD, Nielsen GH, Grum-Schwensen B, Ambartsumian N, Lukanidin E, Grigorian M. Metastasis-inducing S100A4 and RANTES cooperate in promoting tumor progression in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manes S, Mira E, Colomer R, Montero S, Real LM, Gomez-Mouton C, Jimenez-Baranda S, Garzon A, Lacalle RA, Harshman K, et al. CCR5 expression influences the progression of human breast cancer in a p53-dependent manner. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1381–1389. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stormes KA, Lemken CA, Lepre JV, Marinucci MN, Kurt RA. Inhibition of metastasis by inhibition of tumor-derived CCL5. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;89:209–212. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-5328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bieche I, Lerebours F, Tozlu S, Espie M, Marty M, Lidereau R. Molecular profiling of inflammatory breast cancer: identification of a poor-prognosis gene expression signature. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6789–6795. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luboshits G, Shina S, Kaplan O, Engelberg S, Nass D, Lifshitz-Mercer B, Chaitchik S, Keydar I, Ben-Baruch A. Elevated expression of the CC chemokine regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) in advanced breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4681–4687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sauer G, Schneiderhan-Marra N, Kazmaier C, Hutzel K, Koretz K, Muche R, Kreienberg R, Joos T, Deissler H. Prediction of nodal involvement in breast cancer based on multiparametric protein analyses from preoperative core needle biopsies of the primary lesion. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3345–3353. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaal-Hahoshen N, Shina S, Leider-Trejo L, Barnea I, Shabtai EL, Azenshtein E, Greenberg I, Keydar I, Ben-Baruch A. The chemokine CCL5 as a potential prognostic factor predicting disease progression in stage II breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4474–4480. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soria G, Yaal-Hahoshen N, Azenshtein E, Shina S, Leider-Trejo L, Ryvo L, Cohen-Hillel E, Shtabsky A, Ehrlich M, Meshel T. Concomitant expression of the chemokines RANTES and MCP-1 in human breast cancer: a basis for tumor-promoting interactions. Cytokine. 2008;44:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dupre SA, Redelman D, Hunter KW., JR The mouse mammary carcinoma 4T1: characterization of the cellular landscape of primary tumours and metastatic tumour foci. Int J Exp Pathol. 2007;88:351–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2007.00539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niwa Y, Akamatsu H, Niwa H, Sumi H, Ozaki Y, Abe A. Correlation of tissue and plasma RANTES levels with disease course in patients with breast or cervical cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tedla N, Palladinetti P, Wakefield D, Lloyd A. Abundant expression of chemokines in malignant and infective human lymphadenopathies. Cytokine. 1999;11:531–540. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soria G, Ofri-Shahak M, Haas I, Yaal-Hahoshen N, Leider-Trejo L, Leibovich-Rivkin T, Weitzenfeld P, Meshel T, Shabtai E, Gutman M, et al. An inflammatory network in breast cancer: coordinated expression of TNFα & IL-1β with CCL2 & CCL5 and effects on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:130–149. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohl CA, Strauss CE, Misura KM, Baker D. Protein structure prediction using Rosetta. Methods Enzymol. 2004;383:66–93. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw JP, Johnson Z, Borlat F, Zwahlen C, Kungl A, Roulin K, Harrenga A, Wells TN, Proudfoot AE. The x-ray structure of RANTES: heparin-derived disaccharides allows the rational design of chemokine inhibitors. Structure. 2004;12:2081–2093. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, III, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, et al. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soria G, Meshel T, Ben-Baruch A. Chemokines in human breast tumor cells: modifying their expression levels and determining their effects on the malignancy phenotype. Methods Enzymol. 2009;460:3–16. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)05201-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feniger-Barish R, Yron I, Meshel T, Matityahu E, Ben-Baruch A. IL-8-induced migratory responses through CXCR1 and CXCR2: association with phosphorylation and cellular redistribution of focal adhesion kinase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2874–2886. doi: 10.1021/bi026783d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strous GJ, van Kerkhof P, van Meer G, Rijnboutt S, Stoorvogel W. Differential effects of brefeldin A on transport of secretory and lysosomal proteins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2341–2347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller SG, Carnell L, Moore HH. Post-Golgi membrane traffic: brefeldin A inhibits export from distal Golgi compartments to the cell surface but not recycling. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:267–283. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams RC, Jr, Caplow M, McIntosh JR. Cytoskeleton. Dynamic microtubule dynamics. Nature. 1986;324:106–107. doi: 10.1038/324106a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coue M, Brenner SL, Spector I, Korn ED. Inhibition of actin polymerization by latrunculin A. FEBS Lett. 1987;213:316–318. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cingolani LA, Goda Y. Actin in action: the interplay between the actin cytoskeleton and synaptic efficacy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:344–356. doi: 10.1038/nrn2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]