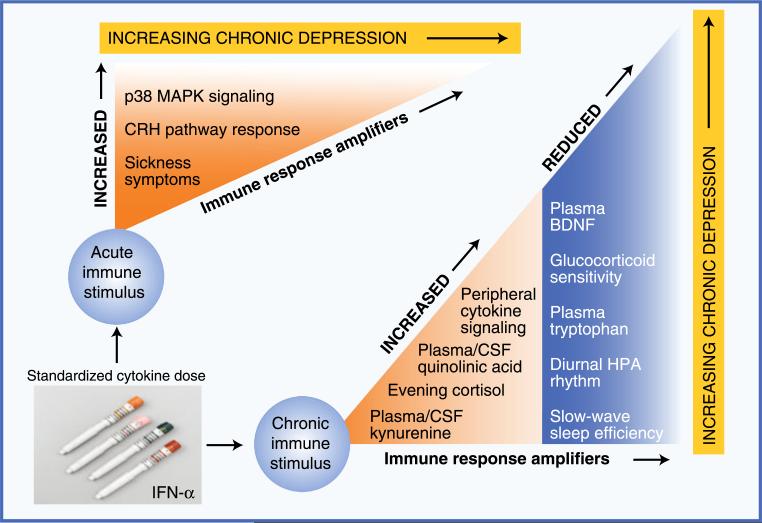

Fig. 1.

Evidence supporting the importance of immune response amplifiers in the etiology of immune-based depression. Studies using exposure to a constant dosage of inflammatory input have identified multiple pathways by which immune activation produces depressive symptoms. This figure illustrates patterns of physiologic vulnerability in such pathways, using treatment with interferon (IFN)-α as a model system for chronic cytokine exposure. Immune response amplifiers identified in response to an initial dose of IFN-α include increased activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), an important intracellular proinflammatory signaling cascade, and increased response of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) pathways. Although not a physiologic pathway per se, increased sickness-type symptoms in response to a first dose of IFN-α predict the later development of full major depressive disorder. In terms of patterns of functional disability in response to chronic cytokine exposure, evidence suggests that individuals with any of the following changes are at significantly increased risk of developing significant depressive symptoms during IFN-α treatment: 1) increased peripheral proinflammatory cytokine concentrations (eg, tumor necrosis factor-α or interleukin-6), 2) flattening of the diurnal cortisol rhythm and increased evening cortisol, 3) increased peripheral and central nervous system concentrations of kynurenine and its metabolite quinolinic acid, and 4) disrupted sleep as reflected by reduced slow-wave sleep and diminished sleep efficiency. Importantly, all these changes have been observed in the context of idiopathic major depressive disorder in medically healthy individuals. BDNF—brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CSF—cerebrospinal fluid; HPA—hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (axis)