Abstract

DNA repair is expected to be a modulator of underlying mutation rates, however the major factors affecting the distribution of DNA repair pathways have not been determined. The Proteomic Constraint theory proposes that mutation rates are inversely proportional to the amount of heredity information contained in a genome, which is effectively the proteome. Thus, organisms with larger proteomes are expected to possess more efficient DNA repair. We show that an important factor influencing the presence or absence of four DNA repair genes mutM, mutY, mutL, and mutS is indeed the size of the bacterial proteome. This is true both of intracellular and other bacteria. In addition, the relationship of DNA repair to genome GC content was examined. In principle, if a DNA repair pathway is biased in the types of mutations it corrects, this may alter the genome GC content. The presence of the mismatch repair genes mutL and mutS was not correlated with genome GC content, consistent with their involvement in an unbiased DNA repair pathway. In contrast, the presence of the base excision repair genes mutM and mutY, whose products both correct GC → AT mutations, was positively correlated with genome GC content, consistent with their biased repair mechanism. Phylogenetic analysis however indicates that the relationship between the presence of mutM and mutY genes and genome GC content is not a simple one.

Keywords: proteome size, AT bias, DNA repair, bacterial genome

Introduction

DNA repair is fundamental for the survival of organisms but some bacterial genomes, particularly intracellular bacteria, lack DNA repair genes that are well conserved elsewhere (Himmelreich et al., 1996; Glass et al., 2000; Moran and Wernegreen, 2000; Shigenobu et al., 2000; Moran and Mira, 2001; Akman et al., 2002; Moran, 2002; Dale et al., 2003). The reason for these absences is unclear. An explanation is provided by the Proteomic Constraint theory, which proposes a selective pressure proportional to the size of the proteome (defined as the total number of codons) that acts to maintain the integrity of heredity information. The theory proposes that a larger proteome exerts a larger selective pressure (Proteomic Constraint) to minimize the occurrence of mutations (Massey and Garey, 2007; Massey, 2008). This is because the size of the mutational target is larger, and hence the mutational load is likely to be higher. This is expected to result in the evolution and maintenance of proofreading and DNA repair mechanisms. It follows that a reduction in the size of a proteome over evolutionary time will result in a reduction of the selection pressure, leading to loss of proofreading and DNA repair mechanisms. The proteomes of intracellular bacteria, for instance, have undergone sometimes extreme reductions in size, thus the absence of some DNA repair genes is consistent with this explanation. A distinction is made between proteome size and genome size. Not all regions of a genome are under evolutionary constraint; this is especially so in the case of eukaryotes that may have large amounts of junk DNA, but also the case with bacteria; for example, intergenic regions and significant parts of the regulatory regions. The proteome is used as a proxy for the total amount of information in a genome because (1) the large majority of heredity information is protein coding; (2) it is accurate to calculate. Ideally, the regulatory regions should be included in the calculation (Massey, 2008) – but this is difficult to calculate computationally; even if there is an estimate for one species of bacteria, it is not clear how this would vary for all the different species of bacteria with vastly different lifestyles and habitats.

Alternatively, both the action of Muller’s ratchet and increased drift have been invoked to account for a decrease in the strength of selection observed in intracellular genomes (Muller’s ratchet; Lynch, 1996, 1998; Moran, 1996; Brynnel et al., 1998; Lynch and Blanchard, 1998; increased drift; Wernegreen and Moran, 1999; Funk et al., 2001; Herbeck et al., 2003; Fry and Wernegreen, 2005; Mamirova et al., 2007; Kuo et al., 2009). These factors could also account for a reduction in the selection pressure to retain DNA repair genes in intracellular bacterial genomes. However, as formulated these explanations do not apply to extracellular bacteria, as it has been proposed that both Muller’s ratchet and increased drift are a consequence of the intracellular lifestyle.

Differences in DNA repair may potentially influence genome GC content; genome GC contents, particularly of bacteria, have been known to differ widely since the early days of nucleic acid biochemistry, but an accepted explanation is lacking. Various hypotheses fall into two categories; adaptationist and neutralist, and are applicable to all three domains of life. Adaptationist explanations invoke changes in genome GC content as an adaptation to factors such as temperature (body temperature; Bernardi et al., 1988, environmental temperature; Kagawa et al., 1984), halophilic conditions (Kennedy et al., 2001), aerobic environments (Naya et al., 2002), low nitrogen environments (Dufresne et al., 2005), high UV environments (Singer and Ames, 1970), or energetic costs (Rocha and Danchin, 2002). Neutralist explanations invoke changes in mutation bias as a cause of variations in genome GC content (Freese, 1962; Sueoka, 1962). In principle, if a DNA repair pathway preferentially corrects GC → AT or AT → GC mutations, then it has the potential to alter the genome GC content (King and Jukes, 1969). This assumes that most mutations are neutral, or nearly neutral. While changes in mutation bias is a potential proximate cause for differences in genome GC content, the ultimate (mechanistic) cause remains elusive and is addressed here.

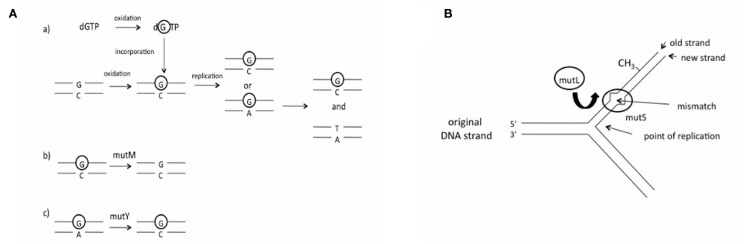

The hypothesis that differences in DNA repair has led to changes in genome GC content has not been tested, and if correct it is unclear which genes amongst the many DNA repair genes are responsible for exerting an effect on genome GC content. The gene products of mutM and mutY, which are components of the base excision repair (BER) pathway, may be able to influence genome GC content, as they both correct GC → AT mutations (Michaels et al., 1991; Noll et al., 1999; Figure 1A). Consequently, it has been demonstrated that deletion of the Salmonella typhimurium mutM and mutY BER genes leads to an elevation in GC → AT mutations (Lind and Andersson, 2008), consistent with findings regarding deletion of these genes in Escherichia coli (mutY, Nghiem et al., 1988; mutM, Cabrera et al., 1988), Helicobacter pylori (mutY, Kulick et al., 2008), and Neisseria meningitidis (mutY, Davidsen et al., 2005). Unbiased DNA repair pathways include the mismatch repair (MMR) pathway. The pathway recognizes seven of the eight possible mismatches in bacteria (Lahue et al., 1989). In contrast to mutM and mutY, deletion of each of the mutL and mutS MMR genes (Figure 1B) in E. coli results in a large increase in transitions (Schaaper and Dunn, 1987), but these do not show a difference in GC/AT mutation bias compared to wild type strains (Schaaper et al., 1986), consistent with the unbiased nature of the MMR pathway.

Figure 1.

The BER and MMR pathways (A) The role of the products of the mutM and mutY genes in the BER pathway. (a) Oxidation of guanine to 8-oxoguanine (circled G) occurs either before or after incorporation of dGTP into the DNA strand; (b) mutM removes 8-oxoguanine that is present in double-stranded DNA; (c) mutY removes a mismatched adenine that is incorporated opposite 8-oxoguanine. (B) The role of the products of the mutL and mutS genes in the MMR pathway. The mutS gene product recognizes a mismatched basepair in the DNA strand after replication. The mutL gene product is recruited to the complex, while the mutH gene product is used to identify the original DNA strand, which is methylated, from the newly replicated DNA strand.

In the analyses described here, the distribution of genes involved in the biased BER pathway and the unbiased MMR pathway were compared to proteome sizes and genome GC contents, across 699 complete bacterial genomes. Proteome size is shown to be a factor influencing the presence or absence of DNA repair genes in bacterial genomes. A positive relationship between genome GC content and the presence of the biased repair mutM and mutY genes is shown, indicating that they may be an influence on genome GC content. However, phylogenetic analysis indicates that the relationship is not a simple one.

Materials and Methods

Gene and genome data

All 699 completed bacterial genomes present in the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) database (Joint Genomes Institute) on 14th January 2009 were used for analysis. DNA repair genes chosen for the analysis were mutM (8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase) and mutY (adenine DNA glycosylase; BER) and mutL and mutS (MMR). These are the best characterized members of a biased DNA repair pathway (BER) and an unbiased DNA repair pathway (MMR). The presence or absence of the genes in complete genomes was initially determined using gene annotations. Genomes that lacked an annotated gene were then Blast searched using the respective gene sequence from a related bacterium, chosen according to the relationships displayed at the NCBI microbial Blast web-site (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sutils/genom_table.cgi), in order to verify the absence of the gene. Hits of an expect value below E−15 were discounted. In the interests of accuracy, for each gene this process was conducted manually and separately by two workers, the gene identifications were subsequently cross checked after the genes were identified from their IMG annotations, and subsequently any additional homologs identified by Blast searching were cross checked. Proteome sizes were calculated from the respective GenBank genome entries using a Perl script that counted the amino acids present in predicted ORFs, and included plasmids.

The definitions of the different bacterial phenotypes analyzed in the study were as follows. Intracellular bacteria were defined as those bacteria that have an obligate intracellular existence in a host cell, extracellular bacteria are defined as all remaining bacteria; these may live outside a host cell but inside host tissue, or may live in the environment without a close association with another organism, these are termed free living bacteria. Pathogenic bacteria have the ability to act as a pathogen. They may be host associated or opportunistic. Host associated pathogenic bacteria are those that reside within or on a host for any part of their lifecycle and typically cause disease, while opportunistic pathogens do not necessarily reside in or on a host, and if they do, do not typically cause disease. Some bacteria may be both commensal and pathogenic; these are classified as host associated pathogens and include H. pylori and Xylella fastidiosa. Host associated pathogenic bacteria may be intracellular or extracellular.

Testing the differences of means

Mean genome GC contents and proteome sizes were generated for genomes that possessed or lacked individual DNA repair genes. The differences in these means were examined statistically. The datasets generated were not normally distributed (data not shown); skew in the data may affect Student’s t-test (Bridge and Sawilowsky, 1999). Thus, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was conducted on the datasets. While gain/loss events are likely to be nested amongst lineages, this is expected to affect N, however the test is of facility in determining a non – significant difference in means.

Use of the phi coefficient to analyze gene interactions

The co-distribution of the four DNA repair genes in the 699 genomes was examined by using the phi coefficient. This was conducted as follows on each pairwise combination of genes (six in total). The tabulated data were transformed into binary notation whereby 0 represented the absence of a gene in a genome and 1 represented the presence of a gene in a genome. The data were inputted into the following equation:

where Φ is the phi coefficient, and the values a, b, c, d refer to the table below

| Gene y |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Gene present) | 0 (Gene absent) | ||

| 1 (Gene present) | a | b | Gene z |

| 0 (Gene absent) | c | d | |

A significant correlation (Φ = +0.3 to +0.7 is a weak positive association, Φ = +0.7 to +1.0 is a strong positive association) can be interpreted two ways: either there is a positive epistatic interaction between the two genes leading to a selective pressure to maintain the two genes in the genome, or similar mutational pressures lead to a selective pressure for maintenance of the two genes in the genome. The latter assumes that the two genes are involved in repairing the same types of mutations. This methodology may be applied to other gene pairs in bacterial genomes for the detection of previously uncharacterized epistatic interactions.

Phylogenetic reconstruction

A species tree of those cyanobacteria used in the comparative genomics analysis was reconstructed using 16S rRNA sequences. The Muscle program (Edgar, 2004) was used to construct an alignment and the jModelTest program (Posada, 2008) was used to estimate model parameters of GTR matrix with a gamma parameter of 0.54 and a proportion of invariant sites of 0.55. Then, the MrBayes program (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) was used to infer phylogeny using a burn in of 25% of generations and building a consensus tree from the last 25% of generations. A species tree of the alphaproteobacteria species used in the comparative genomics analysis was reconstructed using the same methodology as for cyanobacteria, but with a gamma parameter of 0.58 and a proportion of invariant sites of 0.43.

Results and Discussion

Factors affecting the presence or absence of DNA repair genes

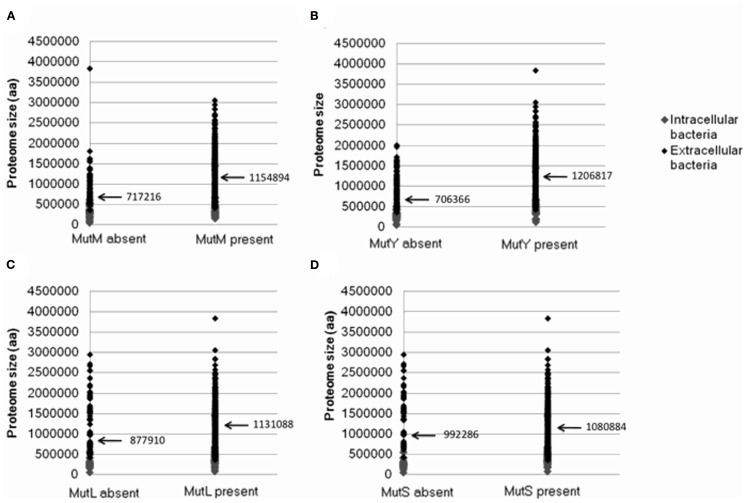

As discussed above, a factor suggested to increase the loss of DNA repair genes is a reduction in the size of the Proteomic Constraint, resulting from a reduction in proteome size (Massey, 2008). A reduced Proteomic Constraint can account for the absence of mutM and mutY (mean proteome sizes where mutM and mutY are absent are 717216 and 706366 amino acids, respectively; mean proteome sizes where present are 1154894 and 1206817 amino acids, respectively; Table 1; Figure A1 in Appendix). Additional factors are present, since not only bacteria with reduced proteome sizes lack mutM or mutY; these remain to be elucidated. mutL and mutS are not influenced as strongly by the size of the proteome (mean proteome sizes where mutL and mutS are absent are 877910 and 992286 amino acids, respectively; mean proteome sizes where present are 1131088 and 1080884 amino acids, respectively; Table 1; Figure A1 in Appendix). A potential reason for the weaker relationship with proteome size, compared to mutM and mutY, is that there is a greater selective pressure to maintain the mutL and mutS genes, indicated by the smaller number of genes absent from the 699 genomes (123 and 83, respectively, compared to 135 and 189 for mutM and mutY, respectively; Table 1). To mitigate the potential effects of sample bias, the analysis was repeated with one species from each genus, with the same conclusions (Table 1). The loss or absence of DNA repair genes in smaller proteomes may help explain the inverse relationship between genome/proteome size and mutation rates (Drake, 1991; Drake et al., 1998; Massey, 2008).

Table 1.

Mean GC contents and proteome sizes of bacterial genomes that possess or lack the DNA repair genes mutM, mutY, mutL, and mutS.

| Gene | Number of genes absent from 699 total genomes or 604 genomes from extracellular bacteria | Mean GC content if gene present (%) | Mean GC content if gene absent (%) | p-Value (Mann–Whitney) | Mean proteome size if gene present (codons) | Mean proteome size if gene absent (codons) | p-Value (Mann–Whitney) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | |||||||

| mutM | 135 | 50.5 | 38.2 | 3.1E−21 | 1154894 | 717216 | 9.2E−18 |

| 94 (extracellular) | 52.4 | 39.9 | 4.6E−18 | 1239048 | 885246 | 4.0E−11 | |

| mutY | 189 | 51.9 | 38.1 | 6.3E−35 | 1206817 | 706366 | 1.2E−27 |

| 129 (extracellular) | 52.9 | 41.5 | 1.7E−19 | 1262652 | 894257 | 1.4E−13 | |

| mutL | 123 | 48.1 | 48.1 | ns | 1131088 | 877910 | 1.9E−7 |

| 93 (extracellular) | 49.8 | 53.9 | 3.9E−3 | 1226575 | 1068544 | 5.1E−4 | |

| mutS | 83 | 47.7 | 51.2 | 0.03 | 1080884 | 992286 | 0.02 |

| 50 (extracellular) | 49.1 | 64.5 | 8.4E−17 | 1158575 | 1454162 | 8.0E−4 | |

| Gene | Number of genes absent from 272 total genomes or 234 extracellular genomes | Mean GC content if gene present (%) | Mean GC content if gene absent (%) | p-Value (Mann–Whitney) | Mean proteome size if gene present (codons) | Mean proteome size if gene absent (codons) | p-Value (Mann–Whitney) |

| B | |||||||

| mutM | 59 | 52.4 | 40.0 | 9.1E−10 | 1208453 | 760976 | 1.3E−9 |

| 41 (extracellular) | 54.2 | 43.3 | 3.4E−7 | 1298041 | 960711.9 | 1.4E−6 | |

| mutY | 79 | 53.2 | 41.1 | 2.0E−11 | 1258561 | 751846 | 1.7E−11 |

| 56 (extracellular) | 54.5 | 45.2 | 9.8E−7 | 1327864 | 956273.1 | 8.5E−7 | |

| mutL | 47 | 50.0 | 47.8 | ns | 1167556 | 842510 | 2.6E−5 |

| 32 (extracellular) | 51.7 | 56.2 | 0.03 | 1258482 | 1115556 | 0.02 | |

| mutS | 35 | 49.8 | 48.9 | ns | 1145003 | 883780 | 0.002 |

| 20 (extracellular) | 51.2 | 63.7 | 7.9E−6 | 1226206 | 1375153 | ns (0.56) | |

A Mann–Whitney test was conducted to test the significance of the difference in the means of GC content and proteome size, between the genomes that possess a gene and those that do not. “ns” denotes “not significant.” Table (A) shows the results of the analysis on the entire dataset, (B) shows results of the analysis on the dataset where only one species was selected from each genus.

Given that DNA repair genes are more likely to be absent in bacteria with small proteomes, this may explain an intriguing feature of intracellular bacterial genomes; their high substitution rates (discussed in Massey, 2008). A high substitution rate is likely to indicate a high underlying mutation rate (Itoh et al., 2002), which may be caused by the loss of DNA repair. The Proteomic Constraint theory therefore indirectly explains the high mutation/substitution rates of intracellular bacteria by proposing that a reduction in size of the proteome reduces the constraint on genetic fidelity, resulting in the loss of DNA repair genes, leading to an elevation in mutation rates (Massey, 2008). The data support this interpretation. In addition, the data show that extracellular bacteria with smaller proteome sizes also have a tendency to lack the four DNA repair genes. This observation may explain the increase in substitution rates of cyanobacteria such as Prochlorococcus marinus SS120 and MED4 (Dufresne et al., 2005), and the increase in mutation rate in Oenococcus oeni (Marcobal et al., 2008), which are both unusual for being free living bacteria that have undergone reductions in the sizes of their proteomes.

The two alternative explanations of Muller’s ratchet and/or an increase in drift may also explain the absence of DNA repair genes in intracellular bacteria. However, they do not explain the absence of DNA repair genes in extracellular bacteria with smaller proteome sizes. This then casts doubt on the explanations of Muller’s ratchet and/or increased drift for the absence of DNA repair genes in intracellular bacteria; given the free living status of these bacteria they are both unlikely to operate. However, the Proteomic Constraint theory provides an explanation for the absence of DNA repair genes in these bacteria. Lastly, it may be hypothesized that larger genomes possess more genes, and are therefore more likely to possess more DNA repair genes, simply by chance, However, this is not likely if it is accepted that the presence of genes in a genome are maintained by natural selection. A pertinent comment to this effect was made by Daubin and Moran (2004).

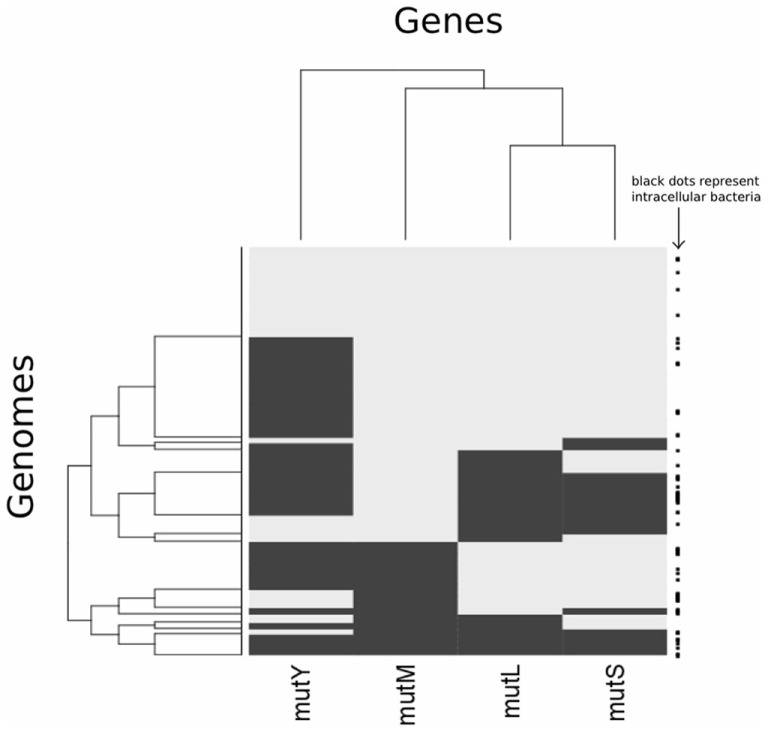

Analysis of different gene pairs reveals that only mutL and mutS are significantly co-distributed (Table 2; Figure A2 in Appendix). This is despite the observation that the presence of all four genes is influenced by the same factor, proteome size. The co-distribution of mutL and mutS can be explained as they have a protein–protein interaction as a vital part of the MMR pathway (Schofield et al., 2001). Even though mutM and mutY are components of the same pathway, the data indicate that they do not have an epistatic interaction, indicating that their function is not interdependent. Therefore, it is not clear if BER is best described as a “pathway.” The function of mutY is not as important as that of mutM, given that it is absent in more genomes than mutM.

Table 2.

Φ Coefficient for pairwise distributions of DNA repair genes.

| Gene pairs | mutL–mutS | mutM–mutY | mutM–mutL | mutL–mutY | mutM–mutS | mutS–mutY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total dataset (699 genomes) | 0.66 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.10 |

| Extracellular bacteria (604 genomes) | 0.70 | 0.32 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.08 | −0.12 |

The Φ coefficient was calculated as described in Section “Materials and Methods,” for each pairwise combination of the genes mutM, mutY, mutL, and mutS.

The analysis is consistent with the theory of a “Proteomic Constraint” operating on the genetic information system. Implicit in this is that mutation rate modulator genes (i.e., DNA repair genes) should be influenced by the size of the proteome; when large there should be more selective pressure to evolve and maintain mutation modulators that reduce mutation rates, when small such mutation modulators are more likely to be lost.

Investigating the relationship of DNA repair genes to pathogenicity

Although there is a difference in average proteome sizes of pathogenic versus non-pathogenic extracellular bacteria (Table 3), this was not found to be significant. No clear link was found between the lack of DNA repair genes and pathogenicity in general (Table 3), although mutY is more likely to be present in pathogenic extracellular bacteria. As many of the pathogenic bacteria in the dataset are opportunistic pathogens it would seem that there is no link between the presence/absence of these genes and a predisposition for pathogenicity, with the possible exception of mutY. When host associated extracellular pathogenic bacteria were compared with the remaining extracellular bacteria, no substantial differences were observed (Table 3) again with the exception of mutY, which is more likely to be present in host associated extracellular pathogenic bacteria. Possibly, mutY has a role in combating the mutagenic (oxidizing) conditions of the innate immune system. The average proteome size of host associated extracellular pathogenic bacteria was smaller than that of the other extracellular bacteria (1094197 codons compared to 1198376 codons), but this was not significant.

Table 3.

Gene contents of pathogenic and non-pathogenic extracellular bacteria 604 extracellular bacterial genomes were examined for their average proteome sizes, average GC contents, and gene contents.

| Extracellular pathogens (237 genomes) | Extracellular non-pathogens (367 genomes) | p-Value (Mann–Whitney) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | |||

| Mean proteome size (codons) | 1139797 | 1202806 | ns |

| Mean GC content | 49% | 51% | 0.045 |

| Percentage that lack mutM | 24 | 24 | – |

| Percentage that lack mutY | 42 | 72 | – |

| Percentage that lack mutL | 31 | 31 | – |

| Percentage that lack mutS | 25 | 20 | – |

| Host associated extracellular pathogens (82 genomes) | Other extracellular bacteria (522 genomes) | p-Value (Mann–Whitney) | |

| B | |||

| Mean proteome size (codons) | 1094197 | 1198376 | ns |

| Mean GC content | 50% | 50% | No difference in the means |

| Percentage that lack mutM | 22 | 25 | – |

| Percentage that lack mutY | 46 | 64 | – |

| Percentage that lack mutL | 30 | 31 | – |

| Percentage that lack mutS | 20 | 21 | – |

| Intracellular bacteria (95 genomes) | Extracellular bacteria (604 genomes) | p-Value (Mann–Whitney) | |

| C | |||

| Mean proteome size (number of codons) | 342246 | 1183493 | 2.0E–50 |

| Mean GC content | 34% | 50% | 2.6E–29 |

| Percentage that lack mutM | 46 | 25 | – |

| Percentage that lack mutY | 72 | 61 | – |

| Percentage that lack mutL | 40 | 31 | – |

| Percentage that lack mutS | 44 | 23 | – |

(A) Pathogenic (opportunistic and host associated) extracellular bacteria were compared with non-pathogenic extracellular bacteria; (B) host associated pathogenic extracellular bacteria were compared with all other extracellular bacteria; (C) Intracellular bacteria were compared with extracellular bacteria. “ns” denotes not significant.

When intracellular bacterial genomes are compared to extracellular bacterial genomes, intracellular bacteria are much more likely to lack the four DNA repair genes than extracellular bacteria (Table 3). This may be attributed to either their intracellular habit (i.e., the effects of Muller’s ratchet/increased drift or a diminished exposure to mutagens), or their sometimes extreme reduction in proteome size, causing a reduction in the proposed Proteomic Constraint.

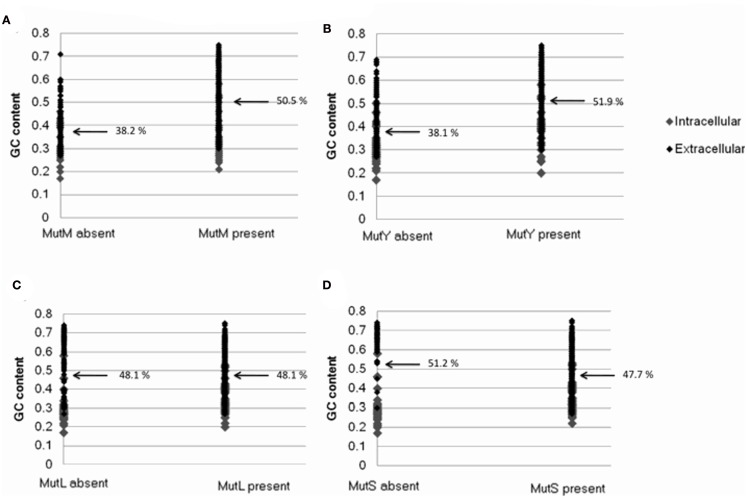

The relationship between DNA repair and genome GC content

Bacterial genomes that lack mutM and mutY were found to be substantially more AT biased on average than those that possess the genes (50.5% GC and 51.9% GC where mutM and mutY are present, respectively; 38.2% GC and 38.1% GC where they are absent; Table 1; Figure A3 in Appendix). This may be understood by the observation that the enzymes encoded by these genes correct GC → AT mutations, and deletion of these genes in experimental systems significantly affects mutation biases. Consistent with this interpretation, genomes that lack mutL and mutS are not more AT biased than those that do not (51.9% GC and 47.7% GC where mutL and mutS are present, respectively; 51.9% GC and 51.2% GC where they are absent; Table 1; Figure A3 in Appendix). Likewise, this is explained by the observation that the enzymes encoded by these genes are involved in an unbiased DNA repair pathway.

The dataset of bacterial genomes contains the genomes of 95 intracellular bacteria; these may be subject to unusual evolutionary dynamics so the analysis was repeated using extracellular and free living bacteria only. The results were essentially unchanged, with all four genes showing a positive relationship with proteome size, and a positive correlation between the presence of mutM and mutY, and genome GC content (Table 1). This demonstrates that the relationship between reduced proteome size and absence of DNA repair genes is not due to the inclusion of intracellular bacteria in the original dataset. Likewise, the relationship between absence of mutM and mutY and AT bias is not due to the inclusion of intracellular bacteria in the original dataset, many of which may be strongly AT biased. To mitigate the potential effects of sample bias, only one species from each genus was selected and the analysis repeated, again with the same qualitative results (Table 1).

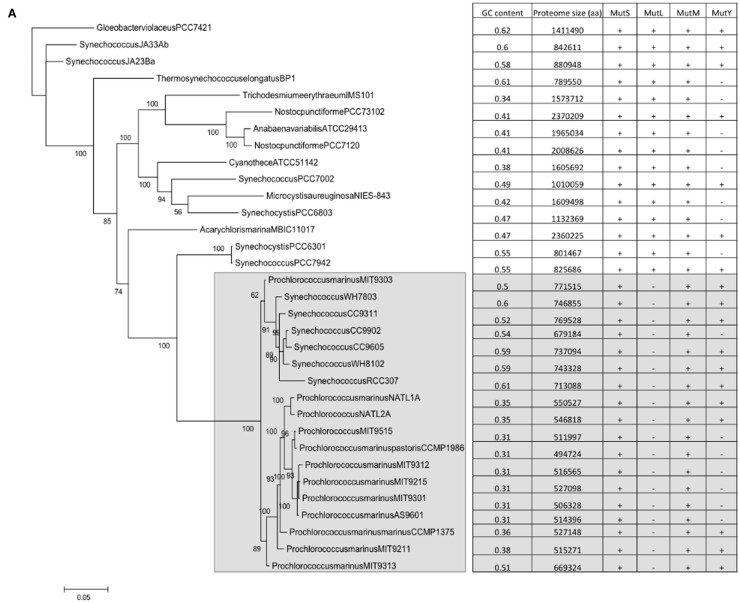

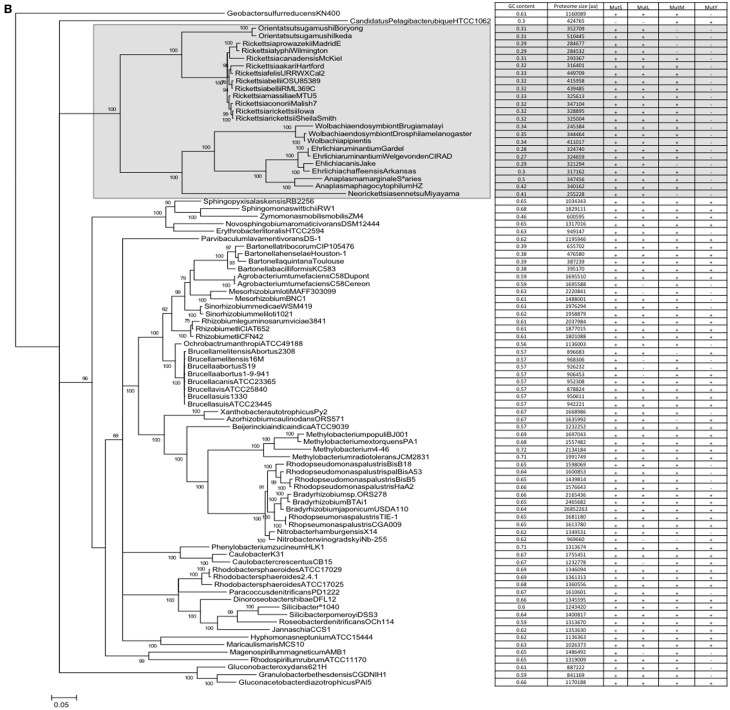

A correlation does not automatically assume causality. However, as there is a mechanistic explanation for the correlations, a case can be made for causality, i.e., that the presence/absence of mutM and mutY has an effect on genome GC content. However, the datapoints represented by individual genomes are not independent; loss/gain events of the genes are nested within nodes of a phylogenetic tree. In order to dissect the possible effects of this phylogenetic non-independence, phylogenetic trees were constructed for the cyanobacterial and alpha bacterial genomes utilized in the study. When the presence or absence of mutM, mutY, mutL, and mutS are superimposed on the trees, the relationship with GC content becomes more complex. For example, a large clade of cyanobacteria containing all the Prochlorococcus strains and six Synechococcus strains (indicated in Figure 2A) does not appear to show a relationship between the absence of mutY and lowered GC content. Likewise, in the Rickettsia and Wolbachia/Ehrlichia clades of the alphaproteobacteria (indicated in Figure 2B) both show lowered GC contents, but the values do not appear to be related to the absence of mutM, which has sporadic distribution in the clades (although mutY is absent throughout). So, it would seem either that the impact of these genes on genome GC content is minimal or that there are confounding factors that moderate their influence.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic trees of the cyanobacteria and alphaproteobacteria, with genome GC contents and presence of DNA repair genes (A) Cyanobacteria; (B) Alphaproteobacteria. Trees were constructed as described in Section “Materials and Methods.” Numerals refer to posterior probability.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Biology Department, University of Puerto Rico – Rio Piedras. Aurian Garcia-Gonzalez was supported by Amgen BioMinds and INBRE scholarships. We would like to thank Dr Henner Brinkmann (Universite de Montreal) for advice on rooting of the two phylogenetic trees. This work was supported by NSF grant 0959864.

Appendix

Figure A1.

The relationship between the presence or absence of genes involved in DNA repair and proteome size. Plots show presence or absence of (A) mutM (B) mutY (C) mutL (D) mutS. Data was generated from 699 complete eubacterial genomes. Intracellular and extracellular bacteria are indicated.

Figure A2.

Heatmap clustering analysis showing presence/absence of mutM, mutY, mutL and mutS across genomes. Rows represent genomes and columns represent genes. Black denotes absence of a gene in a particular genome, while gray indicates presence. The clustering of columns follows the complete linkage method, as implemented in the R statistical package. The right hand side of the plot displays whether a genome belongs to a bacterium that is intracellular (black square).

Figure A3.

The relationship between the presence/absence of genes involved in DNA repair and bacterial genome GC content. Plots show presence or absence of (A) mutM (B) mutY (C) mutL (D) mutS. Data was generated from 699 complete eubacterial genomes. Intracellular and extracellular bacteria are indicated.

References

- Akman L., Yamashita A., Watanabe H., Oshima K., Shiba T., Hattori M., Aksoy S. (2002). Genome sequence of the endocellular obligate symbiont of tsetse flies, Wigglesworthia glossinidia. Nat. Genet. 32, 402–407 10.1038/ng986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi G., Mouchiroud D., Gautier C., Bernardi G. (1988). Compositional patterns in vertebrate genomes: conservation and change in evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 28, 7–18 10.1007/BF02143493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge P. D., Sawilowsky S. S. (1999). Increasing physicians’ awareness of the impact of statistics on research outcomes: comparative power of the t-test and Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test in small samples applied research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 52, 229–235 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00168-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brynnel E. U., Kurland C. G., Moran N. A., Andersson S. G. (1998). Evolutionary rates for tuf genes in endosymbionts of aphids. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 574–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera M., Nghiem Y., Miller J. H. (1988). MutM, a second mutator locus in Escherichia coli that generates G.C-T.A transversions. J. Bacteriol. 170, 5405–5407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale C., Wang B., Moran N., Ochman H. (2003). Loss of DNA recombinational repair enzymes in the initial stages of genome degeneration. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 1188–1194 10.1093/molbev/msg138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubin V., Moran N. A. (2004). Comment on “The origins of genome complexity.” Science 306, 978a. 10.1126/science.1100559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidsen T., Bjoras M., Seeberg E. C., Tonjum T. (2005). Antimutator role of DNA glyscosylase MutY in pathogenic Neisseria species. J. Bacteriol. 187, 2801–2809 10.1128/JB.187.8.2801-2809.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake J. W. (1991). A constant rate of spontaneous mutation in DNA-based microbes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 7160–7164 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake J. W., Charlesworth B., Charlesworth D., Crow J. F. (1998). Rates of spontaneous mutation. Genetics 148, 1667–1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne A., Garczarek L., Partensky F. (2005). Accelerated evolution associated with genome reduction in a free-living prokaryote. Genome Biol. 6, R14. 10.1186/gb-2005-6-2-r14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 10.1093/nar/gkh180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freese E. (1962). On the evolution of base composition of DNA. J. Theor. Biol. 3, 82–101 10.1016/S0022-5193(62)80005-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fry A. J., Wernegreen J. J. (2005). The roles of positive and negative selection in the molecular evolution of insect endosymbionts. Gene 355, 1–10 10.1016/j.gene.2005.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk D. J., Wernegreen J. J., Moran N. A. (2001). Intraspecific variation in symbiont genomes: bottlenecks and the aphid-Buchnera association. Genetics 157, 477–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass J. I., Lefkowitz E. J., Glass J. S., Heiner C. R., Chen E. Y., Cassell G. H. (2000). The complete sequence of the mucosal pathogen Ureaplasma urealyticum. Nature 407, 757–762 10.1038/35037619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbeck J. T., Funk D. J., Degnan P. H., Wernegreen J. J. (2003). A conservative test of genetic drift in the endosymbiotic bacterium Buchnera: slightly deleterious mutations in the chaperonin groEL. Genetics 165, 1651–1660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelreich R., Hilbert H., Plagens H., Pirkl E., Li B.-C., Herrmann R. (1996). Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 4420–4449 10.1093/nar/24.22.4420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T., Martin W., Nei M. (2002). Acceleration of genomic evolution caused by enhancd mutation rate in endocellular symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12944–12948 10.1073/pnas.192449699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa Y., Nojima H., Nukiwa N., Ishizuka M., Nakajima T., Yasuhara T., Tanaka T., Oshima T. (1984). High guanine plus cytosine content in the third letter of codons of an extreme thermophile. DNA sequence of the isopropylmalate dehydrogenase of Thermus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 2956–2960 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S. P., Ng W. V., Salzberg S. L., Hood L., DasSarma S. (2001). Understanding the adaptation of Halobacterium species NRC-1 to its extreme environment through computational analysis of its genome sequence. Genome Res. 11, 1641–1650 10.1101/gr.190201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J. L., Jukes T. H. (1969). Non-Darwinian evolution. Science 164, 788–798 10.1126/science.164.3881.788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulick S., Moccia C., Kraft C., Suerbaum S. (2008). The Helicobacter pylori mutY homologue HP0142 is an antimutator gene that prevents specific C to A transversions. Arch. Microbiol. 189, 263–270 10.1007/s00203-007-0315-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C. H., Moran N. A., Ochman H. (2009). The consequences of genetic drift for bacterial genome complexity. Genome Res. 19, 1450–1454 10.1101/gr.091785.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahue R. S., Au K. G., Modrich P. (1989). DNA mismatch correction in a defined system. Science 245, 160–164 10.1126/science.2665076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind P. A., Andersson D. I. (2008). Whole-genome mutational biases in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17878–17883 10.1073/pnas.0804445105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. (1996). Mutation accumulation in transfer RNAs: molecular evidence for Muller’s ratchet in mitochondrial genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 13, 209–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. (1998). Mutation accumulation in nuclear, organelle, and prokaryotic transfer RNA genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 14, 914–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., Blanchard J. L. (1998). Deleterious mutation accumulation in organelle genomes. Genetica 102/103, 29–39 10.1023/A:1017022522486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamirova L., Popadin K., Gelfand M. S. (2007). Purifying selection in mitochondria, free-living and obligate intracellular proteobacteria. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 17 10.1186/1471-2148-7-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcobal A. M., Sela D. A., Wolf Y. I., Makarova K. S., Mills D. A. (2008). Role of hypermutability in the evolution of the genus Oenococcus. J. Bacteriol. 190, 564–570 10.1128/JB.01457-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey S. E. (2008). The proteomic constraint and its role in molecular evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 2557–2565 10.1093/molbev/msn210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey S. E., Garey J. R. (2007). A comparative genomics analysis of codon reassignments reveals a link with mitochondrial proteome size and a mechanism of genetic code change via suppressor tRNAs. J. Mol. Evol. 64, 399–410 10.1007/s00239-005-0260-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels M. L., Pham L., Cruz C., Miller J. H. (1991). MutM, a protein that prevents G-C-T-A transversions, is formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 3629–3632 10.1093/nar/19.13.3629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran N. (2002). Microbial minimalism: genome reduction in bacterial pathogens. Cell 108, 583–586 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00665-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran N. A. (1996). Accelerated evolution and Muller’s ratchet in endosymbiotic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 2873–2878 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran N. A., Mira A. (2001). The process of genome shrinkage in the obligate symbiont Buchnera aphidicola. Genome Biol. 2, 54. 10.1186/gb-2001-2-12-research0054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran N. A., Wernegreen J. J. (2000). Lifestyle evolution in symbiotic bacteria: insights from genomics. Trends Ecol. Evol. (Amst.) 15, 321–326 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01902-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naya H., Romero H., Zavala A., Alvarez B., Musto H. (2002). Aerobiosis increases the genomic guanine plus cytosine content (GC%) in prokaryotes. J. Mol. Evol. 55, 260–264 10.1007/s00239-002-2323-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nghiem Y., Cabrera M., Cupples C. G., Miller J. H. (1988). The mutY gene: a mutator locus in Escherichia coli that generates G.C-T.A transversions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 2709–2713 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll D. M., Gogos A., Granek J. A., Clarke N. D. (1999). The C-terminal domain of the adenine-DNA glycosylase MutY confers specificity for 8-oxoguanine.adenine mispairs and may have evolved from MutT, an 8-oxo-dGTPase. Biochemistry 38, 6374–6379 10.1021/bi990335x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D. (2008). jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1253–1256 10.1093/molbev/msn083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha E. P. C., Danchin A. (2002). Base composition bias might result from competition for metabolic resources. Trends Genet. 18, 291–294 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02690-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaper R. M., Danforth B. N., Glickman B. W. (1986). Mechanisms of spontaneous mutagenesis: an analysis of the spectrum of spontaneous mutation in the Escherichia coli lacI gene. J. Mol. Biol. 189, 273–284 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90509-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaper R. M., Dunn R. L. (1987). Spectra of spontaneous mutations in defective in mismatch Escherichia coli strains correction: the nature of in vivo DNA replication errors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 6220–6224 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield M. J., Nayak S., Scott T. H., Du C., Hsieh P. (2001). Interaction of Escherichia coli mutS and mutL at a DNA mismatch. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28291–28299 10.1074/jbc.C100449200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigenobu S., Watanabe H., Hattori M., Sakaki Y., Ishikawa H. (2000). Genome sequence of the endocellular bacterial symbiont of aphids Buchnera sp. APS. Nature 407, 81–86 10.1038/35024074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer C. E., Ames B. N. (1970). Sunlight radiation and bacterial DNA ratios. Science 170, 822–826 10.1126/science.170.3954.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueoka N. (1962). On the genetic basis of variation and heterogeneity of DNA base composition. Genetics 48, 582–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernegreen J. J., Moran N. A. (1999). Evidence for genetic drift in endosymbionts (Buchnera): analyses of protein-coding genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 83–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]