Abstract

Vertebrate and invertebrate colour pattern determination mechanisms are considered distinct; recently, however, both fish and butterfly colour patterns have been partly explained by reaction-diffusion mechanisms. Here, we show that multi-coloured eyespots of the spotted mandarin fish, which are reminiscent of butterfly eyespots, are determined by the serial induction of colour patterns. The morphological characterisation of eyespots indicates a sequence of colour pattern development and dynamic interactions between eyespots. A substantial part of an eyespot can be surgically removed and is then reconstructed by regeneration. Strikingly, ectopic patterns are induced by damage at a background (eyespotless) area, but focal damage did not change the eyespot size. Early stages of damage repair were accompanied by calcium oscillations. These results demonstrate that fish eyespots are determined by serial induction, which is likely based on a reaction-diffusion mechanism. These findings suggest mechanistic similarities between the fish and butterfly systems.

Vivid colour patterns are widespread in the animal kingdom. Two notable examples are tropical fish and insect body surface patterns. Fish skin colour patterns are very diverse and are often variable even among individuals of a given species. Their complex colour patterns can mostly be explained by reaction-diffusion models1,2,3, the basis of which is the activator-inhibitor system of short-range self-activation and long-range inhibition4,5. In contrast, insect body surface patterns are usually species-specific. Recent studies revealed that the black spots on the wings of Drosophila species are controlled by the spatially specified expression of certain genes6,7. Similarly, in butterflies, some specific genes are expressed in specific locations in developing wings8,9; thus, overall patterns are largely species-specific. A general colour pattern of butterfly wings is known as the nymphalid groundplan10,11,12, in which several eyespots are regularly aligned. These observations suggest that the colour patterns of insects including butterflies are “fixed” and that their developmental determination mechanisms are different from those of fish colour patterns. Indeed, butterfly eyespots have long been explained by the concentration gradient model for positional information8,10,11,13,14,15,16.

However, recent studies have questioned the validity of the gradient model for butterfly eyespots, and as an alternative, the induction model was proposed17,18. The induction model has been validated to some extent by experimental results19. The mechanistic explanation of the induction model is based on reaction-diffusion equations for the dynamic signal interactions, similar to those of fish eyespots, although additional mechanisms to specify the initiation sites may be required in butterfly eyespots. However, we have noticed that some fish species have distinct eyespots that are reminiscent of butterfly eyespots. Although mechanisms for determining fish skin colour patterns have been well studied1,2,3,20,21,22,23,24,25,26, the previous studies of fish patterns have focused on stripes or random dots, not including eyespots, and there are no experimental results that have directly compared fish eyespots with the butterfly wing colour pattern system.

To examine the convergence between the fish and butterfly systems at the mechanistic level, we investigated the colour patterns of the spotted mandarin fish (Fig. 1a, b), whose eyespots appear to be present at reproducible positions in this species together with those of the spotted ray (Fig. 1c). We named the mandarin fish eyespots as D1 to D7 for the dorsal spots and S1 to S6 for the side (lateral) spots from the anterior to posterior positions, with an R (right) or L (left) suffix (Fig. 1a, b). Here, we studied the fish eyespots with respect to the results obtained from butterfly eyespots and clarified the similarities between them.

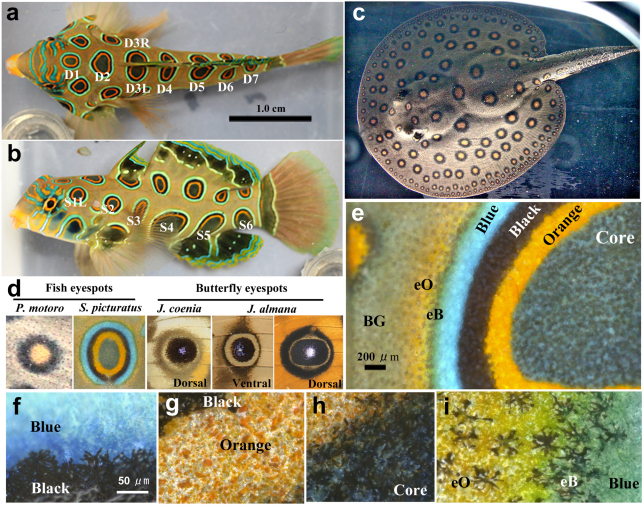

Figure 1. Structures of fish and butterfly eyespots.

(a) Dorsal view of the spotted mandarin fish Synchiropus picturatus. Dorsal eyespots are named from the anterior to posterior direction as D1, D2, and so on. From D3 to D7, two eyespots exist as a pair on both the right and left sides and are termed as D3R and D3L, D4R and D4L, etc. (b) Lateral view of the spotted mandarin fish. Six eyespots are found on each side, and those on the left side are named from the anterior to the posterior as S1L, S2L, etc. (c) Dorsal view of the spotted ray Potamotrygon motoro. The eyespots are circularly arrayed in different distances from the body edge, and inner eyespots are larger than peripheral ones. (d) Representative eyespots of fish and butterflies. Shown from left to right are an eyespot of the spotted ray, a dorsal eyespot of the spotted mandarin fish, a dorsal major forewing eyespot of the buckeye butterfly Junonia coenia, a ventral major forewing eyespot of the peacock pansy butterfly Junonia almana, and a dorsal major forewing eyespot of J. almana. (e) High magnification image of the mandarin fish eyespot. The core contains black, blue, and orange cells and is surrounded by orange, black, and blue rings. The black ring contains black and orange cells, whereas the orange and blue rings contain only orange and blue cells, respectively. Furthermore, eB rings and eO rings exist in most eyespots. BG indicates background. (f–i) Cellular composition of the mandarin fish eyespot. The dendrites of black cells are clearly observed. Blue and orange cells also have similar dendrites, though they are difficult to recognise.

Results

Morphological features of fish eyespots

We first examined the static morphology of the fish eyespots of the spotted mandarin fish and the spotted ray in comparison with the butterfly eyespots of Junonia butterflies (Fig. 1d). In representative regular (or mature) eyespots, we noticed that there is no white focus in fish eyespots, whereas there is a white focus in butterfly eyespots. In addition, the core of the butterfly eyespots is black. This is largely true for the mandarin fish, but the eyespot core is orange in the spotted ray.

In mandarin fish eyespots, a sequential series of rings are found: an outer blue ring, a black ring, an orange ring, and a black core (Fig. 1e). Noticeably, from the blue ring outwards, a narrow but identifiable black ring (termed eB ring; “e” for external or extra) and a diffuse orange ring (termed eO ring) are present. Conceptually, it is possible to find colour symmetry with the central axis located at the blue ring. At the cellular level (Fig. 1f–i), the blue, black, and orange rings almost exclusively contain only blue, black, or orange pigment cells, respectively, but the black core contains black, blue, and orange pigment cells concurrently; however, their proportions vary from eyespot to eyespot. Similarly, all three types of cells are found in the eB and eO rings and background (eyespotless) areas, though the cellular proportions are very different from the black core. These pigment cells have extensive dendrites.

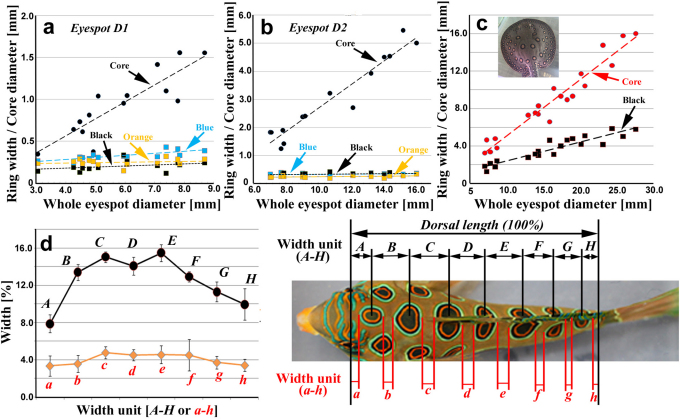

When quantified, the black core size of the mandarin fish was found to dramatically increase when the whole eyespot size increased both in the D1 (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.87; n = 14; Fig. 2a) and D2 eyespots (r = 0.96; n = 14; Fig. 2b). The width of the blue ring also correlates with the whole eyespot size in the D1 eyespot (r = 0.78; Fig. 2a) but not in the D2 eyespot (r = 0.27; Fig. 2b); this is probably because the D1 eyespot is smaller than the D2 eyespot. Black and orange rings do not show significant correlation coefficients either in the D1 eyespot or the D2 eyespot (r ≤ 4.0; n = 14). Thus, these rings are relatively constant over the wide range of eyespot size after a certain width is attained, and the core may enlarge the whole structure of an eyespot (also see Fig. 3d–f).

Figure 2. Morphometric analysis of fish eyespots.

(a) Relationship between whole eyespot size and ring width/core diameter in the D1 eyespots of the spotted mandarin fish (n = 14). (b) Relationship between whole eyespot size and ring width/core diameter in the D2 eyespots of the spotted mandarin fish (n = 14). (c) Relationship between whole eyespot size and ring width/core diameter in a single spotted ray (n = 20). Note that there are four arrays of eyespots parallel to the body outline. Five representative eyespots were taken from each array for measurements. (d) Focal (focus-to-focus) distances and gap (edge-to-edge) distances of dorsal eyespots (n = 11). Measured widths, labelled by uppercase and lowercase alphabets, are shown on the right.

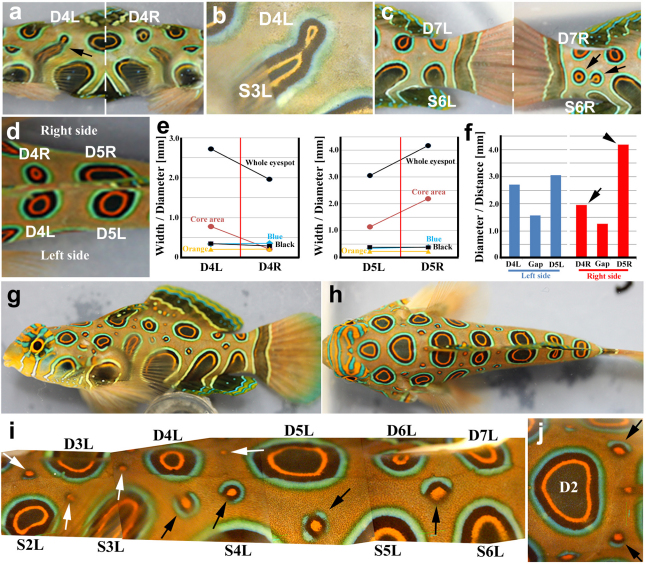

Figure 3. Irregular and miniature eyespots.

(a) Rare eyespot fusion between two eyespots (D4L and S3L, arrow). D4R and S3R are not fused. (b) High magnification of the D4L-S3L fusion. (c) Spontaneous ectopic eyespots between regular eyespots (D7R and S6R, arrows). No ectopic eyespots were observed between D7L and S6L in the same fish. (d) Asymmetric dorsal eyespots. D4R is smaller than D4L, whereas D5R is larger than D5L. (e) Morphometric analysis of the D4 and D5 eyespots of the fish shown in d. Blue, black, and orange rings are similar in width in both L and R eyespots, but the core diameter is not. Whole eyespots and cores are shown as diameters at the largest end along the anterior-posterior axis. (f) Quantitative size relationships among the D4 and D5 eyespots. The right eyespots shown here are unusual in that the D4 eyespot is smaller (arrow), and the D5 eyespot is larger (arrowhead) than the typical eyespots in the same positions. The D4 and D5 left eyespots are similar in size. Eyespot diameters are measured at the larger end along the anterior-posterior axis. “Gap” indicates the edge-to-edge distance between the D4 and D5 eyespots. (g) Lateral view of a fish that has many miniature eyespots of various shapes. (h) Dorsal view of the same fish. (i) High magnification of the lateral view shown in g. All the miniature eyespots are incomplete eyespots. Some eyespots display a core orange area surrounded by very narrow black and blue rings (white arrows). Others have a core orange area surrounded by distinct black and blue rings, but these rings are not closed (black arrows). (j) High magnification of the D2 eyespot with nearby miniature eyespots. Two miniature eyespots are located symmetrically and are symmetrical in shape (arrows).

In the case of the spotted ray, both the core orange area (r = 0.97) and the black ring (r = 0.93) display a high correlation with the whole eyespot size in a given individual (n = 20; Fig. 2c). This suggests that the eyespot size in the spotted ray does not reflect dynamic signal interactions. Instead, they were determined previously, and all the patterns were enlarged as the skin enlarged. This differs from the spotted mandarin fish.

At the level of the entire animal, the eyespot positions in the mandarin fish are apparently fixed in terms of the number of eyespots and their anatomical positions (n = 15 for quantitative evaluation) (Fig. 2d), whereas in the spotted ray, the number of eyespots and their positions vary from individual to individual (n = 4 by visual inspection, data not shown).

Irregular and miniature eyespots

The remainder of this study was performed in the spotted mandarin fish. In most mandarin fish, all the eyespots are positioned symmetrically between the right and left sides of the body. However, in one fish, the D4L and S3L eyespots were fused together, but the D4R and S3R eyespots were not fused (Fig. 3a,b), suggesting homophilic interactions between cells of the same colour. However, eyespots may also repel other eyespots. For example, in a second fish, two ectopic eyespots were found between the D7R and S6R eyespots but not between the D7L and S6L eyespots (Fig. 3c). Notably, the S6R eyespot was much smaller than the S6L eyespot in this fish, probably because of the existence of ectopic eyespots at the position typically occupied by the S6R eyespot.

A pair of dorsal eyespots is symmetrically positioned against the dorsal fin in most mandarin fish, and their size and shape are also very similar. However, we occasionally observed irregular pairs of eyespots (Fig. 3d). Two pairs of sister eyespots, a pair of D4R and D4L eyespots and a pair of D5R and D5L eyespots, were different in the size of the black core, but their blue, black, and orange rings appeared to be similar in width (Fig. 3e), confirming the previous morphological analysis. Furthermore, the smaller D4R eyespot was likely compensated for by the enlarged D5R eyespot (Fig. 3f). This suggests that one eyespot signal suppresses the other eyespot signal despite a lack of physical contact between these eyespots morphologically.

Interestingly, we observed a rare fish in which many “miniature eyespots” were present in the area between the regular eyespots (Fig. 3g–j). In this fish, miniature eyespots appeared to be located at the positions farthest from nearby eyespots. These miniature eyespots probably display the early stages of development of normal eyespots. In these miniature eyespots, the core is orange and is encircled by a narrow black ring. These miniature eyespots do not have a black core. A blue ring is also usually found outside the black ring. However, most of these miniature eyespots are not completely circular and are incomplete or partial eyespots. Indeed, some have only an orange core. Interestingly, a pair of right and left miniature eyespots is often symmetrical in both position and morphology (Fig. 3h, j). It is likely that an orange core induces a black ring and that a black ring subsequently induces the blue ring.

Eyespot reconstruction during skin regeneration

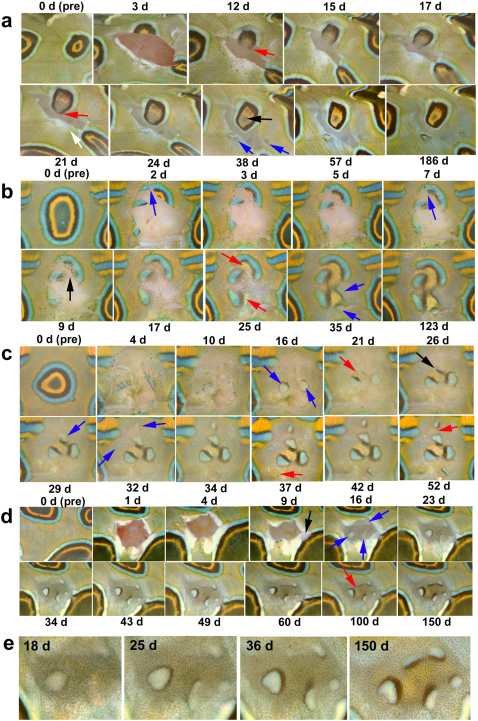

To observe how eyespots are reconstructed during skin regeneration, we surgically removed a portion of skin containing a significant portion of an eyespot (Fig. 4). In all the cases in which the “more-than-half” removal protocol was used (n = 5), most areas regenerated. In the first case shown here, the black core and other portions of an eyespot were removed, the orange and black rings expanded to the wound area, and a blue area was regenerated around it (Fig. 4a). This demonstrates that the black core is not required for the reconstruction of the entire eyespot. Following the closure of the blue and black rings, a black core emerged. Additionally, a blurred blue area was induced along the cut edge, and small ectopic orange cores emerged at irregular positions. In the second sample from the “more-than-half” removal protocol, remnant blue and black rings appeared to behave as seeds for colour patterns (Fig. 4b). An orange area was induced in the positions enclosed by the black areas.

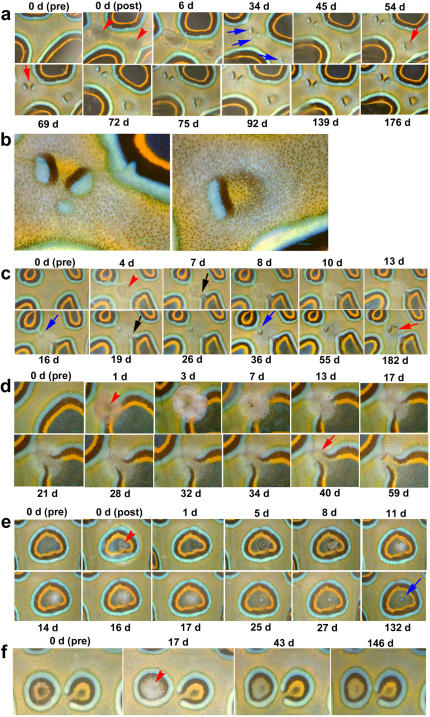

Figure 4. Eyespot reconstruction during skin regeneration.

Days after surgery are indicated at the top or bottom of each panel, and “pre” means pre-surgery. (a) The removal of approximately two-thirds of an eyespot. The remaining rings extended into the damaged area 12 d post-surgery (red arrow) and were connected at 21 d (red arrow). The focal core developed at 38 d (black arrow). Simultaneously, ectopic miniature eyespots developed (blue arrows). (b) The removal of approximately four-fifths of an eyespot. The broken blue rings observed at 2 d were connected at 7 d (blue arrows). The remnant orange area deteriorated at 9 d (black arrow), but new orange areas were induced at 25 d (red arrows). Outside the orange areas, black and blue areas were induced at 35 d (blue arrows). (c) The removal of almost all parts of an eyespot. New blue areas developed at 16 d (blue arrows). An orange area was induced along the narrow black area at 21 d (red arrow). It appears that this subsequently induced a black area at 26 d (black arrow) and a further blue area at 29 d (blue arrow). Small patches of blue areas were also observed at 32 d (blue arrows). At 37 d, a small circular orange area was developed without the normal surrounding black and blue areas (red arrow). An orange area was newly induced at 52 d (red arrow). (d) The removal of a background area. This damage invaded and “opened” the rings of an adjacent eyespot at 9 d (black arrow). Small blue areas developed at 16 d (blue arrows). Narrow black areas were observed around the small blue areas, and an orange area developed between the black and blue areas at 100 d (red arrow). (e) High magnification pictures of emerging colour patterns shown in d. At early stages, a blue area was vaguely surrounded by a narrow black ring. Then, one side of the black ring was widened. Independent blue areas all had widened black areas facing one another. An orange area emerges at later stages in the place that was surrounded by the widened black areas.

We also removed eyespots entirely (n = 5). In all of these cases, some remnants remained, but they appeared to be deconstructed first before small patches of blue areas appeared, which were associated with narrow black areas (Fig. 4c). These black areas then induced adjacent orange areas. The removal of a portion of background area (n = 6) similarly induced small patches of blue areas that were accompanied by small black areas in all the cases (Fig. 4d, e). An orange area was then induced adjacent to the black area. In these samples, a black ring encircled the blue patch, but the black area was wider on one side; therefore, there is an apparent polarity in the development of the black area. It appeared that the side facing other blue areas developed wide black areas despite that there is no apparent physical interactions between remote blue areas.

Ectopic eyespots induced by physical damage

We damaged fish skin using a heated needle on a background (eyespotless) area (n = 23). In 9 out of 23 cases, ectopic colour patterns developed. In the first sample, small patches of blue areas appeared first in the damaged area (Fig. 5a, b). Then, black areas were induced along these blue areas, but there was an apparent polarity in the black induction. Later, orange areas were induced. As a result, bar-like tri-colour bands were often observed. Intriguingly, the orange area induced by the bar-like blue and black areas became circular, and light black and blue rings were observed around the orange area. It appears that an orange area has an intrinsic ability to form a circular pattern. In a second sample, damage to the background (eyespotless) area caused the rings of an adjacent eyespot to open (Fig. 5c), and it appeared that black cells were supplied from the open black ring to the damaged area. These black cells were present around the damaged site for a few days; subsequently, they disappeared. In addition, a small blue patch was “pinched off ” from the blue ring of another eyespot. A black ring encircled the blue area, but the black area was wider at the side that faced the open eyespot.

Figure 5. Damage-induced changes of eyespots.

Days after surgery are indicated at the top or bottom of each panel, and “pre” and “post” mean pre-surgery and post-surgery, respectively. (a) Background damage at two positions (red arrowheads). Small blue areas surrounded by narrow black areas were induced at 34 d (blue arrows). They further induced orange areas at 54 d and 69 d (red arrows). An orange area appears to have induced surrounding circular black and blue structures. (b) High magnification of ectopic colour patterns shown above at 176 d. (c) Background damage at a single position (red arrowhead at 4 d). This damage opened the rings of a nearby eyespot at 7 d (black arrow). It appears that at least the black cells from inside the eyespots have migrated towards the damaged site and can be observed as small dots at the damaged site at 8 d. The open rings became closed at 19 d (black arrow). A portion of the blue area of an adjacent eyespot was “pinched off” towards the damaged site at 16 d (blue arrow) and later established a separate small blue patch surrounded by a narrow black area. Subsequently, an orange area was induced at the centre of the original damage at 182 d (red arrow). (d) Ring damage (red arrowhead at 1 d). After necrotic reactions, blue, black, and orange rings opened, and it appears that cells migrated from inside these rings towards the damaged site. An area of blue ring from another adjacent eyespot was pinched towards the damaged site, and the orange area was induced at 40 d (red arrow). The orange area was more apparent at 59 d. (e) Damage at the core (red arrowhead at 0 d). No overall changes in eyespot size or structure were observed, but the ectopic small blue circular area emerged inside the core of the original eyespot (blue arrow at 132 d). Thin black and orange areas were observed around the ectopic blue area at 132 d. (f) Damage at the core (red arrowhead at 17 d). Narrower images of the treated eyespots at 43 d and at146 d are artefacts of skewed images.

We also damaged the peripheral rings of an eyespot (n = 5). Similar to the findings described above, damage at the outer rings opened those rings and induced a small ectopic circular pattern; its ectopic orange area was connected to the orange ring of the open eyespot (Fig. 5d). During this process, cells appeared to move towards the damaged site from the pre-existing regular eyespot.

We then damaged the black core foci (n = 11). In all cases, no change in size or shape of the damaged eyespots was observed. In 4 out of 11 cases, a small dark blue spot was induced at the damaged site (Fig. 5e). This blue circle was stable for a long period, and black and light orange areas were induced around the black circle. In 7 cases, no blue area was induced (Fig. 5f).

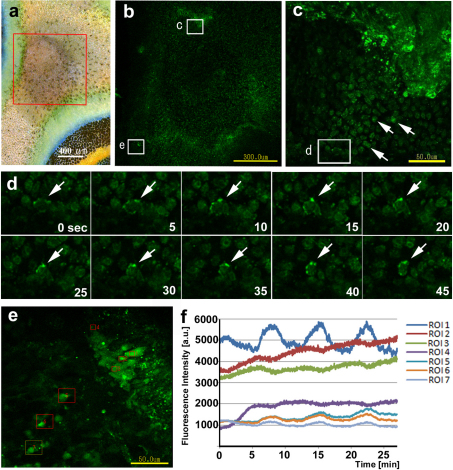

Calcium oscillation induced by physical damage

We examined the physically damaged tissues by calcium imaging techniques (n = 4; Fig. 6). Although we did not observe calcium signals from the non-damaged skin containing eyespots (not shown), in the damaged skin of the background area (Fig. 6a, b), we observed fluorescent cells that were actively moving in the damaged sites (Fig. 6c, d). At least some of those cells displayed fluorescent clusters on the cell membrane that may represent lamellipodia (Fig. 6d). These cells may correspond to pigment cells or related cells that move towards the damaged site, as was observed in the previous damage experiments. They were observed to continue fluorescing when they had stopped moving at a given position (Fig. 6c, e). It is likely that these regions correspond to the prospective blue areas. Similarly, fluorescent cells were observed along the edges of isolated tissues (not shown). Importantly, calcium oscillations with 7–8 min cycles were observed. These oscillations may be synchronised to some extent among the damaged cells (Fig. 6f).

Figure 6. Calcium imaging of physically damaged skin.

(a) An area of skin with background damage approximately 3 h post-treatment. The enclosed area corresponds to the area shown in b. (b) Fluo-4 image of the damaged area. Fluorescent cells are found in the damaged site. Boxes c and e correspond to the areas shown in c and e. (c) A small damaged area. Small fluorescent cells (arrows) move around, but the fluorescing cluster at the top right-hand corner does not. Box d corresponds to the area shown in d. (d) Fluorescent clusters on the cell membrane of a cell at the site shown in c over time. Arrows indicate the identical position of the cell. Fluorescent clusters likely correspond to lamellipodia. (e) A small damaged area. Relatively large fluorescent flat cells are observed. ROI1 to ROI7 are set for monitoring fluorescence dynamics. (f) The change of the mean fluorescence intensity (a.u.) of the ROI shown in e over time. Calcium oscillations of approximately 7–8 min cycles were observed.

Discussion

We characterised natural and artificially induced eyespots of the spotted mandarin fish and compared them to butterfly eyespots. In a mandarin fish eyespot, we observed black cores of various widths and blue, black, and orange rings of relatively constant widths. Furthermore, a very thin black ring (eB ring) and a blurred orange ring (eO ring) were observed outside the blue ring. Larger eyespots had larger black cores, and in relatively small eyespots, the width of the blue ring also correlated with the size of the whole eyespot. Thus, large and small eyespots are structurally different in mandarin fish. When focusing on the three black areas (i.e., black core, black ring, and eB ring) and disregarding the blue and orange rings, it was observed that the black area is narrower as it is located farther from the focus. This was also observed in butterfly eyespots and is called the inside-wide rule. In contrast, large ray eyespots are similar to an enlarged “photocopy” of small eyespots. The ray eyespots are probably “fixed” in the early stage of development because they are similar to the miniature eyespots of the mandarin fish in that the core is orange in colour.

We have shown by measuring the focus-to-focus distances and edge-to-edge distances between eyespots that, similar to those of butterflies, the locations of the dorsal eyespots are fixed characteristics of mandarin fish. This implies the importance of the initial positional specification in mandarin fish. Note that in many mammalian and fish species, including the spotted ray, skin colour patterns vary even among individuals in a given species. At present, we have found no anatomical structure that may specify eyespot positions in the spotted mandarin fish. This differs from butterflies, in which cuticle spots correspond to eyespot foci27.

Possible eyespot interactions include homophilic fusion between rings of the same colour. In addition, a morphometric analysis of irregular eyespots suggests that two eyespots may repel each other. The fact that miniature eyespots are located in the farthest positions from the regular eyespots could also be explained by repelling interactions. These dynamic interactions may be mediated through the so-called “imaginary rings” (including but not limited to eB and eO rings) that are observed in the outermost positions of an eyespot and that are usually invisible or very ambiguous. Alternatively, a concept of developmental field may be suitable. The symmetric positioning of the miniature eyespots suggests that the developmental field is also symmetrical in the right and left sides of the body. These two types of interactions do not necessarily require physical contact between parts of eyespots and are likely to be two important interactions that govern the global colour patterns, which are similar to those found in butterflies19.

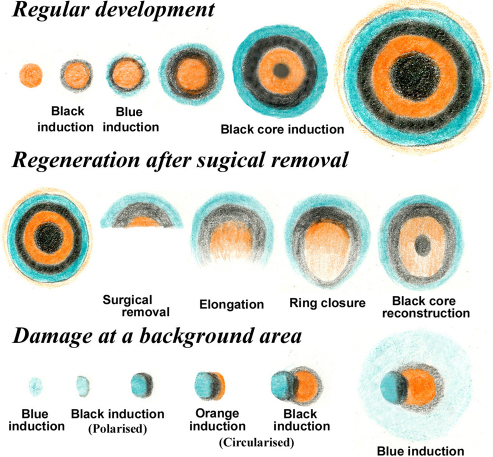

Based on the structures of miniature eyespots, we are able to recapitulate developmental stages of eyespots (Fig. 7, top). Notably, miniature (or immature) eyespots have different colour patterns than those of regular (or mature) eyespots. The core is orange in colour in the miniature eyespots, which is similar to that of butterflies19. Hence, the orange area appears to play a critical role in the initial positioning of the circular pattern. It is likely that other rings are serially induced around the orange core as the whole eyespot size increases. The induced rings increase in width to a certain limit, after which they stay at a constant width. At a critical size for the whole eyespot, the black core emerges in the middle of the orange area.

Figure 7. Summary of the developmental time-course of a mandarin fish eyespot.

Early to mature stages are illustrated from left to right. Regular developmental sequence is different from artificially induced eyespots. The regeneration process indicates that the black core is not necessary to reconstruct the entire eyespot. The serial induction process that is observed in the damage-induced ectopic eyespot also indicates the polarity of the black induction and the circularisation of the orange area.

Regeneration experiments showed that part of an eyespot may be able to reconstruct the full eyespot even without the black core (Fig. 7, middle). Interestingly, the black core was regenerated after ring closure, and then the orange area was observed at the core. These surgical experiments undoubtedly demonstrate that the black core (or a putative organising centre) is not required to regenerate eyespots in this species of fish. The possibility that the pattern determination signals still persist on the naked surface of the detached area is not realistic because when the original eyespots were destroyed, full restoration of the previous eyespot was not realised.

Notably, the background area also has an ability to form new patterns (Fig. 7, bottom). Inducing eyespot damage has been employed to study butterfly colour pattern development10,14,15; however, this method has been applied to vertebrates for the first time in this study. After damage to a background area, a blue area was generated first in most cases. A black area was then induced adjacent to the pre-formed blue area, but the wide black area was formed on only one side. The black induction is “polarised”. This black area then induced an orange area. It appears that the orange area has an intrinsic ability to form a circular pattern. This process does not follow the possible developmental sequence. However, in different cases, an orange area emerged first. The fact that either direction of developmental induction is possible suggests mutual stabilisation between rings of different colours, as observed in the butterfly system17,18. These experiments demonstrate the intrinsic self-organising ability of colour patterns. Polarised induction probably depends on developmental fields that are imposed from the existing colour patterns.

It is interesting to note that when an eyespot ring was opened by damage, the black cells migrated towards the damaged site, as was observed in the zebrafish system23. It is likely that mutual stabilisation between different rings is necessary to maintain the precise eyespot patterns; if a pigment cell is not stabilised in a single position by inhibitory forces from surrounding cells, it is able to move from its original position.

As expected from the results discussed above, focal damage did not affect eyespot size and shape. Initially, this seems to be different from surgical studies of the butterfly forewing eyespots, where focal damage reduced the eyespot size10,13,14,15,16,27. However, the damage-induced size reduction in butterflies has been observed only on the forewing eyespots. The hindwing eyespots are not reduced in size in response to damage, and other homologous elements also do not respond to damage17. In butterflies, the forewing damage that leads to reduced eyespot sizes may cause the extensive removal of position-specifying or signal-generating cells; therefore, such experiments do not necessarily support the conventional gradient model for positional information17,18. In the case of the mandarin fish, a circular blue area was observed at the damaged site in the eyespot core. Therefore, there may be cellular interactions that produce circular clusters of blue cells inside the eyespot core but no such interactions outside an eyespot.

It is somewhat surprising that ectopic eyespots are induced by physical damage on the fish skin as in butterfly wings. We propose that tissue regeneration and colour pattern formation are interconnected both in vertebrates and invertebrates. Signals emitted during skin regeneration for wound healing are likely similar to signals for colour pattern determination in both fish and butterflies.

Given the remarkable similarities between the two systems, it is reasonable to believe that they share a mechanistic principle. A few differences exist between the two systems, but they appear to be marginal rather than fundamental differences. First, there is no apparent binary colour composition in the mandarin eyespots; mandarin eyespots are multi-coloured. In butterflies, binary composition is considered basic colouration18. However, multi-coloured eyespots are also common in butterflies. Second, there is no white focus in fish eyespots, but this white focus is usually present in butterflies. However, there are many butterfly eyespots that lack white foci. Third, miniature eyespots can be incomplete in shape, and a simple band instead of a ring can be formed in fish. Similarly, bar-like or dot-like blue and black bands are induced first in the case of artificial induction. These structures are different from typical butterfly eyespots, but they are similar in shape to partial or “immature” eyespots16 and parafocal elements12. Probably, the largest difference between the two systems is that in fish, pigment cells move in response to surrounding signals, whereas in butterflies, immature scale cells do not move.

Underlying these macroscopic observations are cellular activation, cellular movement, and intracellular interactions, as shown in the zebrafish system21,22,23. We observed mobile cells that exhibit calcium signals around the damaged area where the future colour pattern appears. At least some of these cells displayed fluorescent clusters on their cell membrane, indicating cellular interactions, and several of these cells displayed calcium oscillations. It is reasonable to hypothesise that calcium signals play an important role in skin regeneration and in the induction of colour patterns. Calcium-inducible genes may be responsible for wound healing and colour pattern signalling processes.

Considering the cumulating evidence suggesting that other fish skin colour patterns are determined by reaction-diffusion mechanisms1,2,3,20,21,22,23,24, it is apparent that the mandarin fish colour patterns are also determined by similar mechanisms. The present study demonstrates that mandarin fish eyespot structures are determined by dynamic interactions between colour-specifying signals. Serial induction powered by short-range activation and long-range inhibition4,5 is likely appropriate for describing the developmental dynamics of this fish system and is probably applicable to the butterfly system17,18,19.

Methods

Fish

The orange-spotted ray, Potamotrygon motoro, is a fresh water fish from South America. The spotted mandarin fish, Synchiropus picturatus, is a seawater fish distributed in the tropical Indo-West Pacific coral reefs. The former was obtained from Aqua Wild (Naha, Okinawa, Japan), and the latter was obtained from Pet Box (Chatan, Okinawa, Japan) and the Okinawa Aquarium (Naha, Okinawa, Japan). These fishes do not have scales on the surface.

Structural measurements

Eyespot structures were analysed using digital microscopes VHX-1000 (Keyenece, Osaka, Japan) for high magnification pictures at the cellular level and by SKM-S30A-PC (Saitou Kougaku, Yokohama, Japan) for lower magnification pictures. Quantitative measurements of size and distance were performed using ImageJ28 and graphically presented and analysed using Microsoft Excel. Eyespot diameter and the width of a given ring and core were measured along the line that passes through the focus of that eyespot for the mandarin fish. Similar measurements were taken in the spotted ray except the black ring width, which was calculated by subtracting the core diameter from the whole eyespot size and then dividing it by a factor of two. Five representative eyespots from each array of an individual ray were used for the measurements.

Physical operations

Point-damage (i.e., cautery) operations were performed under general anaesthesia using 2-phenoxyethanol (Wako, Osaka, Japan) in seawater. A stainless-steel needle (177 μm in diameter at the tip and 967 μm wire in diameter) was heated by fire and was pushed onto (but never penetrated into) the skin. For the skin removal operations, a fish was soaked in ice-cold seawater to result in deep general anaesthesia and an area of skin was quickly detached using fine razor blades. The operated individuals were allowed to recover naturally, and pictures were taken as frequently as possible during the recovery process. Three types of detachment surgery protocols were performed: the entire removal of an eyespot (n = 5), a more-than-half removal of an eyespot portion (n = 5), and the removal of a background area (n = 6). In all cases (n = 16 in total), the operated individual survived and removed skin portions were regenerated. Three types of cautery protocols were performed: damage at the focus of an eyespot (n = 11), damage at the peripheral rings of an eyespot (n = 5), and damage at a background area (n = 23). This study was performed in accordance with the Animal Experiment Regulations of University of the Ryukyus approved by the University Committee.

Calcium imaging

For calcium imaging, a portion of skin was removed within 30 sec after the cautery operation, as described above. After washing the surface by gentle vortexing in PBS, the tissue was soaked in PBS containing Fluo-4 AM (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) at a final concentration of 10 μM with brief sonication. Fluo-4 AM was allowed to enter the cells for 20 min, and the tissue was then washed in PBS. The tissue was sandwiched by two thin glasses in PBS and observed. The real-time confocal microscope imaging system used in this study was composed of an inverted epifluorescence microscope Eclipse Ti-U (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), a CSU-X1 laser-scanning unit with a 520±12.5 nm band-pass filter (Yokogawa, Tokyo, Japan), and an ImagEM EM-CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). The AQUACOSMOS/RATIO calcium-ion analysis system (Hamamatsu photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan) was used as the system control software. The exposure time was set at 100 ms with a 1.0 s interval. Autofluorescence from non-damaged tissues with or without fluo-4 loading and from damaged tissues without loading was found to be minimal or null.

Author Contributions

J.M.O. and Y.O. conceived the study, Y.O. performed experiments, J.M.O. and Y.O. analyzed the data, and J.M.O. wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miki Kawauchi, Mariko Teramoto, and Takashi Nakamura for helping us to maintain the fish. We thank Wataru Taira and other members of the BCPH Unit of Molecular Physiology for helpful discussions. This work was partly supported by Research Foundation for Opto-Science and Technology, Hamamatsu, Japan, the Post-COE project for Higher Development and Globalisation for Pacific Coral Reef and Island Studies, and the International Research Hub Project for Climate Change and Coral Reef/Island Dynamics of University of the Ryukyus.

References

- Kondo S. & Asai R. A reaction-diffusion wave on the skin of the marine angelfish Pomacanthus. Nature 376, 765–768 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S., Iwashita M. & Yamaguchi M. How animals get their skin patterns: fish pigment pattern as a live Turing wave. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 53, 851–856 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S. & Miura T. Reaction-diffusion model as a framework for understanding biological pattern formation. Science 329, 1616–1620 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierer A. & Meinhardt H. A theory of biological pattern formation. Kybernetik 12, 30–39 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt H. & Gierer A. Pattern formation by local self-activation and lateral inhibition. BioEssays 22, 753–760 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gompel N., Prud'homme B., Wittkopp P. J., Kassner V. A. & Carroll S. B. Chance caught on the wing: cis-regulatory evolution and the origin of pigment patterns in Drosophila. Nature 433, 481–487 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner T., Koshikawa S., Williams T. M. & Carroll S. B. Generation of a novel wing colour pattern by the wingless morphogen. Nature 464, 1143–148 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beldade P. & Brakefield P. M. The genetics and evo-devo of butterfly wing patterns. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 442–452 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed R. D. et al. optix drives the repeated convergent evolution of butterfly wing pattern mimicry. Science 333, 1137–1141 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhout H. F. The Development and Evolution of Butterfly Wing Patterns. Smithsonian Institution Press, WashingtonDC (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Nihout H. F. Elements of butterfly wing patterns. J. Exp. Zool. 291, 213–225 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otaki J. M. Colour-pattern analysis of parafocal elements in butterfly wings. Entomol. Sci. 12, 74–83 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Nijhout H. F. Pattern formation on lepidopteran wings: Determination of an eyespot. Dev. Biol. 80, 275–288 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhout H. F. Cautery-induced colour patterns in Precis coenia (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae). J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 86, 191–203 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakefield P. M., & French V. Eyespot development on butterfly wings: the epidermal response to damage. Dev. Biol. 168, 98–111 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French V. & Brakefield P. M. Eyespot development on butterfly wings: the focal signal. Dev. Biol. 168, 112–123 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otaki J. M. Colour-pattern analysis of eyespots in butterfly wings: a critical examination of morphogen gradient models. Zool. Sci. 28, 403–413 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otaki J. M. Generation of butterfly wing eyespot patterns: a model for morphological determination of eyespot and parafocal element. Zool. Sci. 28, 817–827 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otaki J. M. Artificially induced changes of butterfly wing colour patterns: dynamic signal interactions in eyespot development. Sci. Rep. 1, 111 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa S., Okamoto M. & Kondo S. Blending of animal colour patterns by hybridization. Nat. Commun. 1, 66 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamasu A., Takahashi G., Kanbe A. & Kondo S. Interactions between zebrafish pigment cells responsible for the generation of Turing patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8429–8434 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M., Yoshimoto E. & Kondo S. Pattern regulation in the stripe of zebrafish suggests an underlying dynamic and autonomous mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 4790–4793 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi G. & Kondo S. Melanophores in the stripes of adult zebrafish do not have the nature to gather, but disperse when they have the space to move. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 21, 677–686 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwashita M., Watanabe M., Ishii M., Chen T., Johnson S. L., Kurachi Y., Okada N. & Kondo S. Pigment pattern in jaguar/obelix zebrafish is caused by a Kir7.1 mutation: implications for the regulation of melanosome movement. PLoS Genet. 2, e197 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M. et al. Spot pattern of leopard Danio is caused by mutation in the zebrafish connexin41.8 gene. EMBO Rep. 7, 893–897 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maderspacher F. & Nüsslein-Volhard C. Formation of the adult pigment pattern in zebrafish requires leopard and obelix dependent cell interactions. Development 130, 3447–3457 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otaki J. M., Ogasawara T. & Yamamoto H. Morphological comparison of pupal wing cuticle patterns in butterflies. Zool. Sci. 22, 21–24 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abràmoff M. D., Magalhães P. J. & Ram S. J. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 11, 36–42 (2004). [Google Scholar]